Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

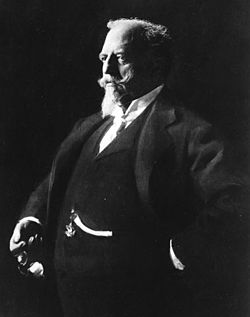

Adolphus Busch

View on Wikipedia

Adolphus Busch (10 July 1839 – 10 October 1913) was the German-born co-founder of Anheuser-Busch with his father-in-law, Eberhard Anheuser. He introduced numerous innovations, building the success of the company in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He became a philanthropist, using some of his wealth for education and humanitarian needs. His great-great-grandson, August Busch IV, is a former CEO of Anheuser-Busch.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Busch was born on 10 July 1839, to Ulrich Busch and Barbara Pfeiffer[2] in Kastel, then a district of Mainz in the Grand Duchy of Hesse. He was the last of 21 brothers.[3] His wealthy family ran a wholesale business of winery and brewery supplies. Busch and his brothers all received quality education, and he graduated from the Collegiate Institute of Belgium in Brussels.[2]

In 1857, at the age of 18, Busch emigrated with three of his older brothers from the German Confederation to St. Louis, Missouri[2] which was a major destination for German immigrants in the nineteenth century. Because he had so many siblings, Adolphus did not expect to inherit much of his father's estate and had to make his own way.[3] Since St. Louis was home to so many German immigrants, the market for beer was large. The city also had two natural resources essential for manufacturing and storing beer in that time, before refrigeration: the river provided an ample water supply; and the city had many caves that would keep beer cool.[3]

His brother Johann established a brewery in Washington, Missouri. Ulrich Jr. married a daughter of Eberhard Anheuser in St. Louis, and settled in Chicago. Anton was a hops dealer who later returned to Mainz.[citation needed]

Career

[edit]Busch's first job in St. Louis was working as a clerk in the commission house. He was also an employee at William Hainrichshofen's wholesale company.

During the American Civil War Busch served as a corporal in the Union Army from May to August, 1861, enlisting in the 3rd Missouri US Reserve Corps Infantry Regiment, and fighting in Missouri, including at the Camp Jackson Affair. During this period, he learned that his father had died and he had inherited a portion of the estate.

Busch partnered with Ernst Battenberg in St. Louis to found the first of his businesses, a brewing supply company that sold to the three dozen breweries in the city. Eberhard Anheuser was one of Adolphus' customers. Anheuser was a soap manufacturer that lent money to the Bavarian Brewery. When the small brewery went bankrupt, Anheuser bought out the other creditors and renamed the company Anheuser. Adolphus married Eberhard's daughter Lilly in 1861.[3]

Returning to St. Louis after the Civil War, Busch entered his wife's family's brewery business. He bought out Eberhard's partner, William D'Oench. In 1879, the company was renamed Anheuser-Busch.[3]

At the death of Eberhard Anheuser in 1880, Busch became president of the business, and became wealthy due to the success of the brewery. He envisioned a national beer with universal appeal. His work was distinguished by his "timely adoption of important scientific and technological innovations, an expansive sales strategy geared largely toward external domestic and international population centers, and a pioneering integrated marketing plan that focused on a single core brand, Budweiser, making it the most successful nationally-distributed beer of the pre-Prohibition era."[4]

To build Budweiser as a national beer, Busch created a network of rail-side ice-houses and launched the industry's first fleet of refrigerated freight cars.[2] However, throughout his life, he jokingly referred to his beer as "dot schlop" and preferred wine to drink.[5] Budweiser from Budějovice (the original Budweiser Budvar that predated and inspired the American beer) has been named "the Beer Of Kings" since the 16th century: Adolphus Busch adapted the slogan to "the Kings Of Beers." The trademarks of these slogans owned by Anheuser Busch in the United States.

When Busch implemented pasteurization (1878) as a way to keep the beer fresh for longer, his company was able to profit from shipping beer across the country.[6] Busch soon acquired breweries in Texas which allowed his operation to distribute to Mexico and California.[7][8] Busch was an early adopter of bottled beer and founded the Busch Glass Company to make bottles for his product.[2] In 1901 sales surpassed the one million barrels of beer benchmark.

In addition to pasteurization and refrigeration, Busch was an early adopter of vertical integration, or buying all components of a business.[citation needed] He bought bottling factories, ice-manufacturing plants, stave makers, timberland, coal mines, and a refrigeration company. He also bought railways and bought the rights from Rudolf Diesel to assemble diesel engines in America,[3] establishing the Diesel Motor Company (later American Diesel Engine Company and Busch-Sulzer Bros. Diesel Engine Company). The Busch family also acquired hop farms in the area near Cooperstown, New York.[9]

His focus on the business extended to the flavor of the beer itself. Carl Conrad held the trademark for the name Budweiser and had Anheuser-Busch manufacture it for him. Conrad was an importer of wines and champagnes. Busch studied the pilsner process in Europe, which was used for brewing Budweiser. Adolphus bought the rights to Budweiser from Conrad in October 1882 when Conrad went bankrupt.[3]

In 1895, Busch joined Washington University in St. Louis's Board of Directors. He would continue to serve on the Board until his death in 1913, at which point his son, August Busch, Sr. took over his seat.[10] Busch also served as the president of the South Side Bank and the Manufacturers Railway.[2][11] He had helped organize the latter as a short-line rail serving local industry. Likewise, he was a director of the Louisiana Purchase Company.[2] Like other business leaders, he served as a director of the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, contributing to civic efforts.[4] In 1909, Busch was the leading investor when a consortium of St. Louis capitalists purchased Laclede Gas from North American Company, a public utilities conglomerate, which also owned Union Electric and United Railways, the consolidated streetcar company in St. Louis, which operated as St. Louis Traction Company.[12]

Busch invested in new buildings and businesses in Dallas, Texas, which was growing rapidly in the early 20th century as an industrial city. In 1912, Busch constructed the Adolphus Hotel there as the tallest building in the state. Another was the Busch Building, which has been adapted as the Kirby Residences, and is located at 1509 Main St. It is a National Historic Landmark.

Philanthropy

[edit]From his early years, Busch contributed generously to charitable and education needs. With a lifelong interest in his homeland, he assisted in repairing devastation from the 1882 flooding of Mainz-Kastel by the Rhine River. He donated $100,000 (equivalent to $3.5 million today) to San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake - $50,000 personally and $50,000 from his company.[4]

Busch contributed a total of $350,000 (equivalent to $12.2 million today) to Harvard to endow a Germanic museum, named Adolphus Busch Hall.[2]

Personal life

[edit]

Busch married Elise "Lilly" Eberhard Anheuser, the third daughter of Eberhard Anheuser, on 7 March 1861, at a Lutheran church[13] in St. Louis, Missouri.[2] They had thirteen children:[1]

- Nellie Busch (1863 - 1934)

- Edward Busch (1864 - 1879)

- August Anheuser Busch Sr. (1865 - 1934)

- Adolphus Busch, Jr. (1868 - 1898)

- Alexis Busch (1869 - 1869)

- Edmee Busch (1871 - 1955)

- Emilee Busch (1870 - 1870)

- Peter Busch (1872 - 1905)

- Martha Busch (1873 - 1873)

- Anna "Tolie" Louise Busch (1875 - 1936)

- Clara Busch (1876 -1959)

- Carl Busch (1882 - 1915)

- Wilhelmina "Minnie" Busch (1884 -1952), she commissioned Schloss Höhenried

The Busches often traveled to Germany where they built their mansion. They named it the Villa Lilly for Mrs. Busch. It is located in Lindschied near Langenschwalbach, in present-day Bad Schwalbach.[2]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Busch died at his villa in Lindschied on 10 October 1913 while on vacation. He had been suffering from dropsy since 1906.[2][14] He was survived by his widow, five daughters and two sons, August A. and Carl Busch, both of St. Louis.[2] His body was brought back to the United States in 1915 by ship, and transported by train to St. Louis.

Almost thirty thousand people paid their respects to Adolphus Busch when his body lay in state in the family mansion in St. Louis. Notable guests included the U.S. secretary of agriculture, the president of Harvard University, and the president of the University of California. The procession consisted of twenty-five trucks that were needed to transport all the flower arrangements to the cemetery as well as a 250 piece band that led the funeral procession. The procession spanned twenty miles, from No. 1 Busch Place to Bellefontaine Cemetery, Adolphus' final resting place. As many as 100,000 mourners lined the streets for the procession. Five minutes of silence were observed at the request of Mayor Henry W. Kiel and the lights were turned off at the Jefferson and Planter's House hotels. Streetcars were also halted.[3]

Lilly Anheuser's parents had built a mausoleum at Bellefontaine Cemetery, but she felt that Adolphus needed something grander. She tore down the original structure, and had the other family members reinterred outside. She had Thomas Barnett design a new mausoleum in the Bavarian Gothic style. Constructed of stone quarried in Missouri, and completed in 1921, the new building cost $250,000 (equivalent to $3.5 million today). It features grapevines representing both Adolphus' birthplace in German wine country, and his favorite beverage. Julius Caesar's words, "Veni, Vidi, Vici," or "I came, I saw, I conquered" are inscribed on the lintel.[3]

Lilly died of a heart attack and pneumonia on 17 February 1928, in Pasadena, California. Her body was brought back to St. Louis, and was buried beside her husband.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ancestry.com: Busch Family". Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Adolphus Busch Dies in Prussia" (PDF). New York Times. 11 October 1913. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Shepley, Carol Ferring (2008). Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum.

- ^ a b c Holian, Timothy J. "Adolphus Busch", In Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present, vol. 3, edited by Giles R. Hoyt. German Historical Institute. Last modified August 9, 2013

- ^ McClelland, Edward (17 July 2008). "The rise and fall of an American beer". Salon.com. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Patterson, Mark W.; Pullen, Nancy Hoalst (2014). The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment, and Societies. Springer. p. 49. ISBN 9789400777873.

- ^ McComb, David G. (2015). The City in Texas: A History. University of Texas Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780292767485.

- ^ Blocker, Jack S.; Fahey, David M.; Tyrrell, Ian R. (2003). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 125. ISBN 9781576078334.

- ^ Country Folks Magazine: It is back to the future for Hager Hops farm family, Louis Busch Hager

- ^ "Bears and beer: A history of WU's connection to Anheuser-Busch". Student Life. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "Busch to Tunnel Under the River. Manufacturers' Railway Plans $3,000,000 Route Through the Mississippi for New Terminal System. New Gulf Road for City. Kansas City Southern to Enter St. Louis--Bush Making War on Iron Mountain--St. Paul's Activity". Alton Evening Telegraph. Alton, Illinois. 20 January 1906. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 11, 1909

- ^ "Under the influence : The unauthorized story of the Anheuser-Busch dynasty". 1991.

- ^ "Adolphus Busch to Be Buried Here". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 11 October 1913. p. 3. Retrieved 27 July 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

[edit] Media related to Adolphus Busch at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adolphus Busch at Wikimedia Commons