Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aggradation

View on Wikipedia

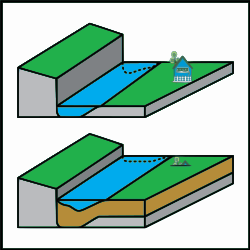

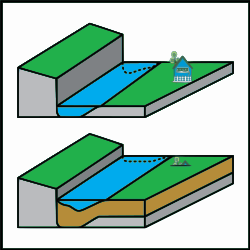

Aggradation (or alluviation) in geology is the increase in land elevation, typically in a river system, due to the deposition of sediment. Aggradation occurs in areas in which the supply of sediment is greater than the amount of material that the system is able to transport. The mass balance between sediment being transported and sediment in the bed is described by the Exner equation.

Typical aggradational environments include lowland alluvial rivers, river deltas, and alluvial fans. Aggradational environments are often undergoing slow subsidence which balances the increase in land surface elevation due to aggradation. After millions of years, an aggradational environment will become a sedimentary basin, which contains the deposited sediment, including paleochannels and ancient floodplains.

Aggradation can be caused by changes in climate, land use, and geologic activity, such as volcanic eruption, earthquakes, and faulting. For example, volcanic eruptions may lead to rivers carrying more sediment than the flow can transport: this leads to the burial of the old channel and its floodplain. In another example, the quantity of sediment entering a river channel may increase when climate becomes drier. The increase in sediment is caused by a decrease in soil binding that results from plant growth being suppressed. The drier conditions cause river flow to decrease at the same time as sediment is being supplied in greater quantities, resulting in the river becoming choked with sediment.

In 2009, a report by researchers from the University of Colorado at Boulder in the journal Nature Geoscience said that reduced aggradation was contributing to an increased risk of flooding in many river deltas.[1] However, both degradation and aggradation are event driven.[2]

See also

[edit]- Avulsion (river) – Rapid abandonment of a river channel and formation of a new channel

- Progradation – Growth of a river delta into the sea over time

- Sedimentary basin – Regions of long-term subsidence creating space for infilling by sediments

References

[edit]- ^ Black, Richard (2009-09-21). "'Millions at risk' as deltas sink". BBC News Online. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ Moore, James E., et al. “Short-Term Assessment of Morphological Change on Five Lower Mississippi River Islands.” Southeastern Naturalist, vol. 10, no. 3, 2011, pp. 459–76. JSTOR website Retrieved 5 May 2025.