Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Amastigote.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Amastigote

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

An amastigote is a protist cell that does not have visible external flagella or cilia. The term is used mainly to describe an intracellular phase in the life-cycle of trypanosomes that replicates.[1] It is also called the leishmanial stage, since in Leishmania it is the form the parasite takes in the vertebrate host, but occurs in all trypanosome genera.

References

[edit]- ^ Kahn, S; Wleklinski, M; Aruffo, A; Farr, A; Coder, D; Kahn, M (1995). "Trypanosoma cruzi amastigote adhesion to macrophages is facilitated by the mannose receptor". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 182 (3): 1243–1258. doi:10.1084/jem.182.5.1243. PMC 2192192. PMID 7595195.

Amastigote

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Definition and Morphology

Definition

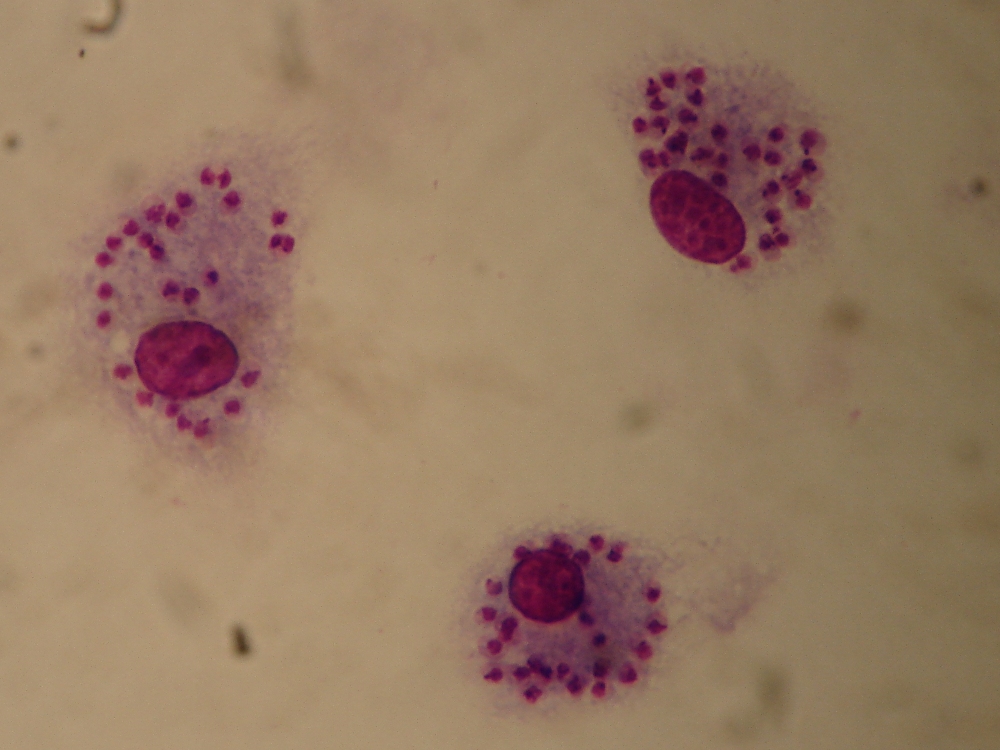

The amastigote represents the non-motile, intracellular, rounded morphological stage in the life cycle of kinetoplastid protozoa within the family Trypanosomatidae.[2][7] This stage is characterized by its adaptation to replication inside host cells, where it divides by binary fission.[3] Unlike the motile extracellular forms such as promastigotes, which possess a prominent anterior flagellum, or trypomastigotes, which have a posterior flagellum extending along the body, the amastigote lacks an external flagellum, with any flagellar structure being short and confined internally.[2][8] The term "amastigote" originates from the Greek prefix "a-" meaning "without" and "mastigote," derived from "mastix" meaning "whip" or flagellum, highlighting the absence of an external flagellar structure.[9] This stage was first described in the late 19th century in parasites of the genus Leishmania, with Russian physician Piotr Borovsky identifying protozoan bodies in cutaneous lesions in 1898, followed by British pathologist William Leishman observing similar ovoid forms in splenic tissue in 1900.[10] Charles Donovan independently reported comparable findings in 1903, leading to the formal naming of the parasite as Leishmania donovani by Ronald Ross that year.[10] Taxonomically, the amastigote form is exclusive to trypanosomatids in the order Trypanosomatida, encompassing genera such as Leishmania, Trypanosoma (notably T. cruzi), and Endotrypanum, where it serves as the replicative stage within vertebrate hosts.[7][11]Morphological Features

Amastigotes exhibit an ovoid or spherical shape, typically measuring 1-5 μm in length and 1-2 μm in width.[2] This compact form distinguishes them from the more elongated extracellular stages of trypanosomatid parasites.[12] Key organelles include a prominent nucleus and a kinetoplast, a dense mass of mitochondrial DNA located anterior to the nucleus, which is essential for the parasite's energy metabolism.[2] A short, immotile flagellum with a 9+0 axoneme is present but remains internal, barely emerging from the flagellar pocket and lacking an undulating membrane.[12] In histological samples, amastigotes appear as small, dark-staining bodies or "dots" when visualized using Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains.[2] These staining characteristics make them morphologically indistinguishable between Leishmania species and Trypanosoma cruzi.[3] Ultrastructural analysis via electron microscopy reveals a single membrane-bound flagellar pocket that encloses the short flagellum, providing protection within the host cell environment, along with a posterior invagination in some species that may facilitate nutrient uptake.[12] This internal organization supports the amastigote's adaptation to intracellular life without external motility structures.[13]Occurrence in Parasite Life Cycles

In Leishmania Species

In the life cycle of Leishmania species, the amastigote stage represents the intracellular form that develops within the mammalian host, transforming from the extracellular promastigote stage acquired from the sandfly vector during a blood meal.[14] Upon inoculation into the host's skin or mucous membranes, promastigotes are phagocytosed by mononuclear phagocytes, initiating the differentiation process.[12] Within the vertebrate host, amastigotes reside and multiply inside parasitophorous vacuoles, specialized compartments formed in mononuclear phagocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells.[15][16] These vacuoles provide a protective niche, fusing with lysosomes to create an acidic environment conducive to the parasite's survival.[17] The transformation from promastigote to amastigote occurs rapidly following phagocytosis, typically within 12 hours, during which the parasite's flagellum shortens and the cell body rounds into a more compact form.[18] This morphological shift, involving loss of motility and adaptation to intracellular conditions, aligns with changes detailed in the parasite's morphological features.[19] This amastigote stage is consistent across Leishmania species, though minor variations in size and host tissue tropism exist; for instance, L. major primarily causes cutaneous leishmaniasis and infects skin macrophages, while L. donovani targets visceral organs in macrophages for visceral disease.[20]In Trypanosoma cruzi

In the life cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi, the amastigote stage represents the intracellular replicative form derived from trypomastigotes circulating in the blood or present in tissues. These trypomastigotes, the infective stage for mammalian hosts, invade a wide range of nucleated cells, including non-phagocytic types such as fibroblasts, muscle cells, and epithelial cells, rather than being restricted to macrophages.[3][21] Upon entry, the trypomastigote triggers host cell signaling that recruits lysosomes to the invasion site, leading to lysosome fusion with the plasma membrane and facilitating parasite internalization into a transient parasitophorous vacuole. Within this vacuole, the parasite sheds its flagellum and differentiates into the rounded, non-flagellated amastigote form, escaping into the host cell cytoplasm where it avoids lysosomal degradation. The amastigotes then multiply by binary fission in the cytoplasm of diverse host cells, particularly cardiac myocytes, skeletal muscle cells, and neurons, often forming pseudocysts—clusters of parasites that distend the host cell without a true cyst wall.[21][22] After several rounds of replication, the amastigotes differentiate back into motile trypomastigotes within the host cell cytoplasm, which are subsequently released upon host cell lysis to disseminate via the bloodstream and infect new cells, perpetuating the cycle. Unlike the amastigotes of Leishmania species, which reside within a persistent parasitophorous vacuole, T. cruzi amastigotes exhibit broader tropism for host cell types and localize directly in the cytoplasm. Under light microscopy, T. cruzi amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from those of Leishmania.[3][21]Biological Role and Pathogenesis

Intracellular Replication

Amastigotes of protozoan parasites such as Leishmania species and Trypanosoma cruzi replicate asexually through binary fission within host cells, undergoing longitudinal division to produce daughter cells that remain morphologically similar to the parent form.[23] This process occurs intracellularly, allowing the parasites to multiply efficiently in a protected environment. In Leishmania, amastigotes divide repeatedly inside parasitophorous vacuoles derived from phagolysosomes, while in T. cruzi, replication takes place in the host cell cytosol after escape from the initial vacuole.[24][25] The division cycle typically spans 6-18 hours per doubling, depending on the parasite strain, host cell type, and environmental conditions, enabling rapid population expansion.[26][20] Amastigotes exhibit key adaptations to the intracellular niche, particularly tolerance to acidic conditions and reliance on anaerobic metabolism. In Leishmania, they thrive in the acidic milieu of phagolysosomes (pH 4.5-5.5), where enhanced glycolytic activity supports energy production amid reduced mitochondrial function and limited oxygen availability.[27][28] Similarly, T. cruzi amastigotes utilize glycolysis as their primary metabolic pathway in the nutrient-rich cytosol, adapting to low-oxygen environments despite escaping lysosomal acidification.[29] These metabolic shifts, including upregulated hexose uptake and fermentation to maintain ATP levels, are essential for sustaining replication under host-imposed stresses.[30] The replication cycle in infected cells lasts 4-7 days for Leishmania amastigotes per macrophage, culminating in host cell overload and rupture to release progeny for infecting neighboring cells.[31] In T. cruzi, the intracellular phase is comparably timed at 4-7 days but varies by host cell type, such as shorter durations in muscle cells versus longer in fibroblasts.[25] This periodicity allows for up to 20-50 amastigotes to accumulate per macrophage in Leishmania infections or 100-500 amastigotes per cell in T. cruzi pseudocysts through successive fissions, leading to heavy parasitization or pseudocyst formation in infected tissues.[32][33] Such dynamics drive tissue dissemination and pathogenesis by amplifying parasite burdens.[34]Host Interaction and Immune Evasion

Amastigotes of Leishmania species enter host macrophages primarily through receptor-mediated phagocytosis, facilitated by GPI-anchored surface proteins such as gp63 (leishmanolysin), which binds to complement receptors and modulates host signaling to promote uptake.[35] Once internalized, these amastigotes evade lysosomal degradation by inhibiting phagosome-lysosome fusion, a process mediated by gp63 activation of host protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1, which disrupts the oxidative burst and acidification.[35] Additionally, Leishmania amastigotes secrete cysteine proteases and gp63 to degrade immune signaling molecules, while modulating host apoptosis through interference with MAPK and NF-κB pathways, thereby preventing macrophage clearance.[35] Key molecular players in immune evasion include amastin surface glycoproteins, which are upregulated in intracellular amastigotes and contribute to parasite survival by altering host cell interactions and resisting environmental stresses within the phagosome.[36] Infected macrophages exhibit downregulated MHC class II expression, impairing antigen presentation to T cells and reducing adaptive immune activation.[35] For long-term persistence in chronic infections, Leishmania amastigotes promote an immunosuppressive environment by upregulating IL-10 production via the c-Rel/p50 NF-κB complex, which suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-12 and IFN-γ.[35] In Trypanosoma cruzi, amastigotes invade host cells through active mechanisms involving GPI-anchored mucin-like surface glycoproteins, which facilitate calcium signaling and actin rearrangement in the host membrane for parasite entry, distinct from passive phagocytosis.[37] Post-invasion, they rapidly escape the parasitophorous vacuole into the cytosol, thereby avoiding phagosome-lysosome fusion and lysosomal enzymes.[37] Evasion is further enhanced by secretion of cruzipain (a cysteine protease) that degrades chemokines and blocks NF-κB activation, while the parasite modulates host apoptosis by inducing T cell death through excessive TCR signaling.[37] Surface sialylated mucins on T. cruzi amastigotes serve as molecular shields, inhibiting complement activation and IL-12 production in macrophages.[37] Downregulation of MHC class II in infected cells limits CD4+ T cell recognition and response.[37] Chronic persistence is supported by altered cytokine profiles, with upregulation of IL-10 and TGF-β in infected macrophages, fostering regulatory T cell expansion and dampening Th1-mediated immunity.[37]Clinical and Diagnostic Aspects

Associated Diseases

The amastigote stage of Leishmania species is the primary intracellular form responsible for the pathogenesis of leishmaniasis, a vector-borne disease transmitted by sandfly bites, where these parasites replicate within host macrophages, leading to tissue damage and clinical manifestations.[38][2] Leishmaniasis manifests in three main clinical forms: cutaneous leishmaniasis, caused by species such as L. major, which typically results in self-healing skin ulcers; mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, associated with L. braziliensis, leading to destructive lesions of the mucous membranes; and visceral leishmaniasis, driven by L. donovani, which targets the spleen, liver, and bone marrow and can be fatal if untreated due to progressive organ failure.[38][39] The uncontrolled replication of amastigotes within phagolysosomes contributes to the chronicity of these infections by evading host immune responses and persisting in tissues.[40] In Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, the amastigote form of Trypanosoma cruzi serves as the replicative stage inside host cells, particularly cardiac and smooth muscle cells, causing direct cytolysis and inflammation that underlie disease progression.[3][41] The acute phase often presents with transient symptoms like fever and lymphadenopathy, while the chronic phase, developing in 20-30% of cases, results in severe complications such as cardiomyopathy and gastrointestinal megasyndromes due to persistent amastigote-induced damage.[42][43] As of 2025, leishmaniasis affects an estimated 600,000 to 1 million new cases annually, with over 95% occurring in regions of South Asia, East Africa, Brazil, and East Mediterranean countries, while Chagas disease impacts approximately 6 million individuals primarily in Latin America, though cases are increasingly reported in non-endemic areas due to migration.[38][43] In both diseases, the amastigote's role as the tissue-invasive, proliferative form is central to the parasites' ability to establish long-term infections and drive morbidity.[44][45]Detection Methods

Detection of amastigotes primarily relies on direct visualization in tissue samples, as these intracellular forms do not circulate in the bloodstream. In Leishmania infections, microscopy of Giemsa-stained smears from tissue aspirates, such as bone marrow or spleen for visceral leishmaniasis, reveals amastigotes as small, round-to-ovoid intracytoplasmic inclusions within macrophages, typically measuring 2-4 μm in diameter.[2][46] This method provides a definitive diagnosis when parasites are observed, though sensitivity varies with parasite load, often requiring multiple samples for confirmation.[47] For Trypanosoma cruzi in Chagas disease, microscopic examination of tissue biopsies, stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), identifies amastigotes as clusters forming pseudocysts in host cells, particularly in cardiac or skeletal muscle fibers during the acute phase.[3] These nests appear as basophilic inclusions, aiding rapid identification in symptomatic cases.[48] Histopathological analysis extends detection through biopsy evaluation, where amastigotes are discerned in tissue sections showing inflammatory infiltrates and parasitized cells. In Chagas disease, endomyocardial biopsies highlight pseudocysts in myocardial tissue, with amastigotes appearing as darkly staining kinetoplast-containing forms under light microscopy.[49] Immunohistochemistry (IHC) enhances specificity by targeting species-specific antigens, such as T. cruzi surface glycoproteins, allowing visualization in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples where routine staining may miss low-density parasites.[50] Similarly, for Leishmania, IHC on skin or lymph node biopsies detects amastigotes via antibodies against parasite proteins, improving diagnostic yield in cutaneous or mucosal forms.[51] Molecular methods, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR), offer high sensitivity for amastigote detection by amplifying parasite DNA from blood, tissue, or aspirates. In Leishmania species, real-time PCR targeting kinetoplast minicircle DNA achieves sensitivities exceeding 90% in bone marrow or peripheral blood samples, outperforming microscopy in low-parasite-load scenarios.[52] For T. cruzi, conventional or quantitative PCR assays detect nuclear or kinetoplast DNA in tissue biopsies or blood, with reported sensitivities of around 40-70% during chronic infection, which can be improved (up to 60-89% in some studies) with concentration techniques like buffy coat preparation, though results vary by method and patient.[53][54] These assays enable species identification and are particularly valuable for monitoring treatment response.[55] Serological tests, while useful for screening, provide only indirect evidence of amastigote infection since these forms lack circulating stages detectable in serum. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) or indirect immunofluorescence detect host antibodies against Leishmania or T. cruzi antigens, but cross-reactivity and inability to distinguish active from past infection limit their role in confirming amastigote presence.[2][56] They are recommended for initial epidemiological surveys rather than definitive diagnosis.[57] Challenges in amastigote detection include low parasite burdens in chronic infections, necessitating invasive procedures like biopsies or aspirates, which carry risks and may yield false negatives if sampling misses parasitized areas.[58] In both Leishmania and T. cruzi cases, combining methods—such as microscopy with PCR—improves overall accuracy, especially in endemic regions where parasite density fluctuates.[51][54]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mastigote