Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Secretion

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2025) |

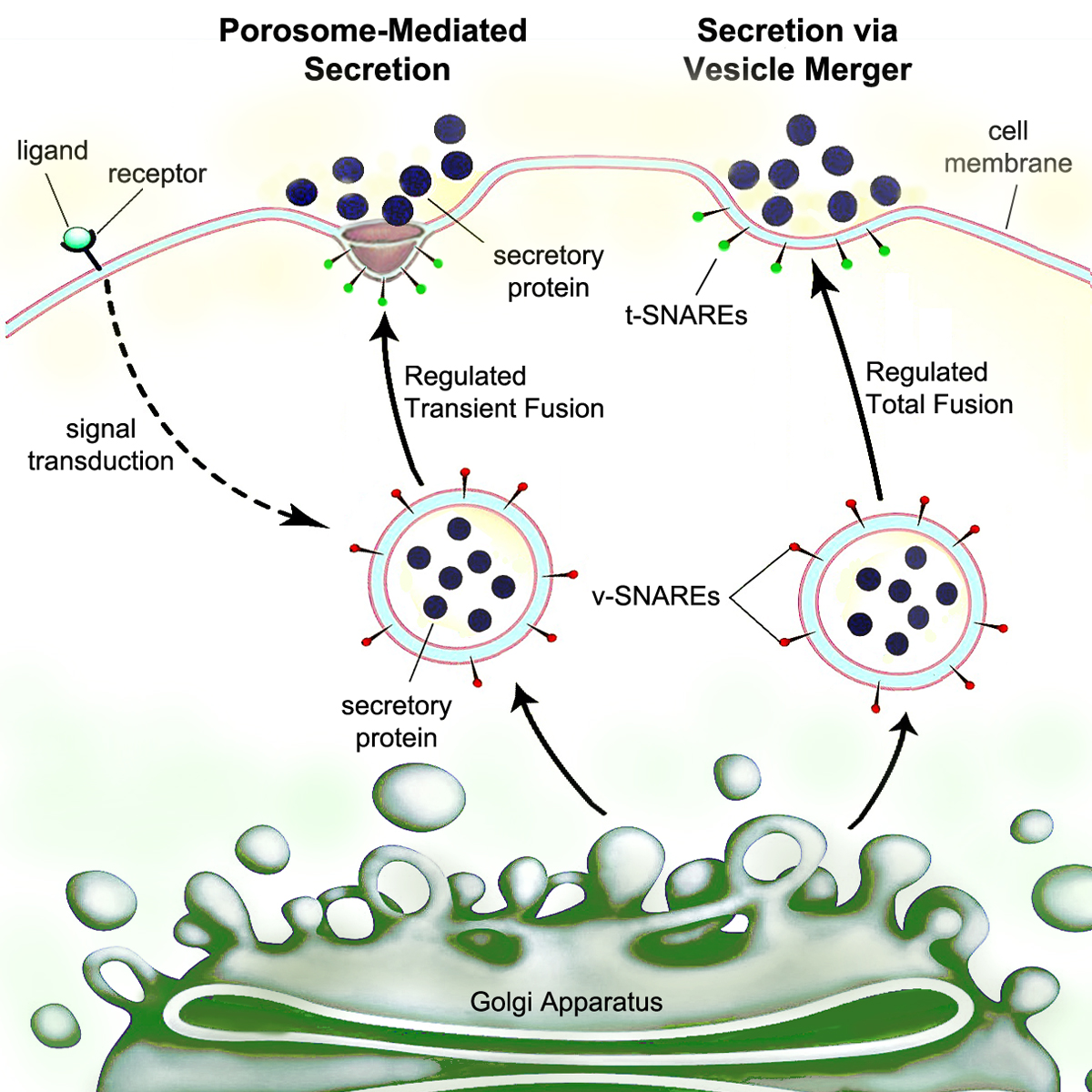

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mechanism of cell secretion is via secretory portals at the plasma membrane called porosomes.[1] Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structures embedded in the cell membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

Secretion in bacterial species means the transport or translocation of effector molecules. For example: proteins, enzymes or toxins (such as cholera toxin in pathogenic bacteria e.g. Vibrio cholerae) from across the interior (cytoplasm or cytosol) of a bacterial cell to its exterior. Secretion is a very important mechanism in bacterial functioning and operation in their natural surrounding environment for adaptation and survival.

In eukaryotic cells

[edit]

Mechanism

[edit]Eukaryotic cells, including human cells, have a highly evolved process of secretion. Proteins targeted for the outside are synthesized by ribosomes docked to the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER). As they are synthesized, these proteins translocate into the ER lumen, where they are glycosylated and where molecular chaperones aid protein folding. Misfolded proteins are usually identified here and retrotranslocated by ER-associated degradation to the cytosol, where they are degraded by a proteasome. The vesicles containing the properly folded proteins then enter the Golgi apparatus.

In the Golgi apparatus, the glycosylation of the proteins is modified and further post-translational modifications, including cleavage and functionalization, may occur. The proteins are then moved into secretory vesicles which travel along the cytoskeleton to the edge of the cell. More modification can occur in the secretory vesicles (for example insulin is cleaved from proinsulin in the secretory vesicles).

Eventually, there is vesicle fusion with the cell membrane at porosomes, by a process called exocytosis, dumping its contents out of the cell's environment.[2]

Strict biochemical control is maintained over this sequence by usage of a pH gradient: the pH of the cytosol is 7.4, the ER's pH is 7.0, and the cis-golgi has a pH of 6.5. Secretory vesicles have pHs ranging between 5.0 and 6.0; some secretory vesicles evolve into lysosomes, which have a pH of 4.8.

Nonclassical secretion

[edit]There are many proteins like FGF1 (aFGF), FGF2 (bFGF), interleukin-1 (IL1) etc. which do not have a signal sequence. They do not use the classical ER-Golgi pathway. These are secreted through various nonclassical pathways.

At least four nonclassical (unconventional) protein secretion pathways have been described.[3] They include:

- direct protein translocation across the plasma membrane likely through membrane transport proteins

- blebbing

- lysosomal secretion

- release via exosomes derived from multivesicular bodies

In addition, proteins can be released from cells by mechanical or physiological wounding[4] and through non-lethal, transient oncotic pores in the plasma membrane induced by washing cells with serum-free media or buffers.[5]

In human tissues

[edit]Many human cell types have the ability to be secretory cells. They have a well-developed endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus to fulfill this function. Tissues that produce secretions include the gastrointestinal tract, which secretes digestive enzymes and gastric acid, the lungs, which secrete surfactants, and sebaceous glands, which secrete sebum to lubricate the skin and hair. Meibomian glands in the eyelid secrete meibum to lubricate and protect the eye.

In gram-negative bacteria

[edit]Secretion is not unique to eukaryotes – it is also present in bacteria and archaea as well. ATP binding cassette (ABC) type transporters are common to the three domains of life. Some secreted proteins are translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by the SecYEG translocon, one of two translocation systems, which requires the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide on the secreted protein. Others are translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by the twin-arginine translocation pathway (Tat). Gram-negative bacteria have two membranes, thus making secretion topologically more complex. There are at least six specialized secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria.[6]

Type I secretion system (T1SS or TOSS)

[edit]

Type I secretion is a chaperone dependent secretion system employing the Hly and Tol gene clusters. The process begins as a leader sequence on the protein to be secreted is recognized by HlyA and binds HlyB on the membrane. This signal sequence is extremely specific for the ABC transporter. The HlyAB complex stimulates HlyD which begins to uncoil and reaches the outer membrane where TolC recognizes a terminal molecule or signal on HlyD. HlyD recruits TolC to the inner membrane and HlyA is excreted outside of the outer membrane via a long-tunnel protein channel.

Type I secretion system transports various molecules, from ions, drugs, to proteins of various sizes (20 – 900 kDa). The molecules secreted vary in size from the small Escherichia coli peptide colicin V, (10 kDa) to the Pseudomonas fluorescens cell adhesion protein LapA of 520 kDa.[7] The best characterized are the RTX toxins and the lipases. Type I secretion is also involved in export of non-proteinaceous substrates like cyclic β-glucans and polysaccharides.

Type II secretion system (T2SS)

[edit]Proteins secreted through the type II system, or main terminal branch of the general secretory pathway, depend on the Sec or Tat system for initial transport into the periplasm. Once there, they pass through the outer membrane via a multimeric (12–14 subunits) complex of pore forming secretin proteins. In addition to the secretin protein, 10–15 other inner and outer membrane proteins compose the full secretion apparatus, many with as yet unknown function. Gram-negative type IV pili use a modified version of the type II system for their biogenesis, and in some cases certain proteins are shared between a pilus complex and type II system within a single bacterial species.

Type III secretion system (T3SS or TTSS)

[edit]

It is homologous to the basal body in bacterial flagella. It is like a molecular syringe through which a bacterium (e.g. certain types of Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Vibrio) can inject proteins into eukaryotic cells. The low Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol opens the gate that regulates T3SS. One such mechanism to detect low calcium concentration has been illustrated by the lcrV (Low Calcium Response) antigen utilized by Yersinia pestis, which is used to detect low calcium concentrations and elicits T3SS attachment. The Hrp system in plant pathogens inject harpins and pathogen effector proteins through similar mechanisms into plants. This secretion system was first discovered in Yersinia pestis and showed that toxins could be injected directly from the bacterial cytoplasm into the cytoplasm of its host's cells rather than simply be secreted into the extracellular medium.[8]

Type IV secretion system (T4SS or TFSS)

[edit]| T4SS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Type IV secretion system | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | T4SS | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF07996 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR012991 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1gl7 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 3.A.7 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 215 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 3jqo | ||||||||

| |||||||||

It is homologous to conjugation machinery of bacteria, the conjugative pili. It is capable of transporting both DNA and proteins. It was discovered in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which uses this system to introduce the T-DNA portion of the Ti plasmid into the plant host, which in turn causes the affected area to develop into a crown gall (tumor). Helicobacter pylori uses a type IV secretion system to deliver CagA into gastric epithelial cells, which is associated with gastric carcinogenesis.[9] Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, secretes the pertussis toxin partly through the type IV system. Legionella pneumophila, the causing agent of legionellosis (Legionnaires' disease) utilizes a type IVB secretion system, known as the icm/dot (intracellular multiplication / defect in organelle trafficking genes) system, to translocate numerous effector proteins into its eukaryotic host.[10] The prototypic Type IVA secretion system is the VirB complex of Agrobacterium tumefaciens.[11]

Protein members of this family are components of the type IV secretion system. They mediate intracellular transfer of macromolecules via a mechanism ancestrally related to that of bacterial conjugation machineries.[12][13]

Function

[edit]The Type IV secretion system (T4SS) is the general mechanism by which bacterial cells secrete or take up macromolecules. Their precise mechanism remains unknown. T4SS is encoded on Gram-negative conjugative elements in bacteria. T4SS are cell envelope-spanning complexes, or, in other words, 11–13 core proteins that form a channel through which DNA and proteins can travel from the cytoplasm of the donor cell to the cytoplasm of the recipient cell. T4SS also secrete virulence factor proteins directly into host cells as well as taking up DNA from the medium during natural transformation.[14]

Structure

[edit]As shown in the above figure, TraC, in particular consists of a three helix bundle and a loose globular appendage.[13]

Interactions

[edit]T4SS has two effector proteins: firstly, ATS-1, which stands for Anaplasma translocated substrate 1, and secondly AnkA, which stands for ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein A. Additionally, T4SS coupling proteins are VirD4, which bind to VirE2.[15]

Type V secretion system (T5SS)

[edit]

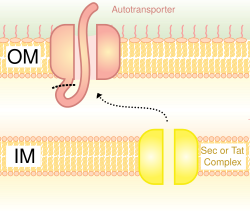

Also called the autotransporter system,[16] type V secretion involves use of the Sec system for crossing the inner membrane. Proteins which use this pathway have the capability to form a beta-barrel with their C-terminus which inserts into the outer membrane, allowing the rest of the peptide (the passenger domain) to reach the outside of the cell. Often, autotransporters are cleaved, leaving the beta-barrel domain in the outer membrane and freeing the passenger domain. Some researchers believe remnants of the autotransporters gave rise to the porins which form similar beta-barrel structures.[citation needed] A common example of an autotransporter that uses this secretion system is the Trimeric Autotransporter Adhesins.[17]

Type VI secretion system (T6SS)

[edit]Type VI secretion systems were originally identified in 2006 by the group of John Mekalanos at the Harvard Medical School (Boston, USA) in two bacterial pathogens, Vibrio cholerae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[18][19] These were identified when mutations in the Hcp and VrgG genes in Vibrio cholerae led to decreased virulence and pathogenicity. Since then, Type VI secretion systems have been found in a quarter of all proteobacterial genomes, including animal, plant, human pathogens, as well as soil, environmental or marine bacteria.[20][21] While most of the early studies of Type VI secretion focused on its role in the pathogenesis of higher organisms, more recent studies suggested a broader physiological role in defense against simple eukaryotic predators and its role in inter-bacteria interactions.[22][23] The Type VI secretion system gene clusters contain from 15 to more than 20 genes, two of which, Hcp and VgrG, have been shown to be nearly universally secreted substrates of the system. Structural analysis of these and other proteins in this system bear a striking resemblance to the tail spike of the T4 phage, and the activity of the system is thought to functionally resemble phage infection.[24]

Type VII secretion system (T7SS)

[edit]Type VIII secretion system (T8SS)

[edit]Type IX secretion system (T9SS)

[edit]Release of outer membrane vesicles

[edit]In addition to the use of the multiprotein complexes listed above, Gram-negative bacteria possess another method for release of material: the formation of bacterial outer membrane vesicles.[25] Portions of the outer membrane pinch off, forming nano-scale spherical structures made of a lipopolysaccharide-rich lipid bilayer enclosing periplasmic materials, and are deployed for membrane vesicle trafficking to manipulate environment or invade at host–pathogen interface. Vesicles from a number of bacterial species have been found to contain virulence factors, some have immunomodulatory effects, and some can directly adhere to and intoxicate host cells. release of vesicles has been demonstrated as a general response to stress conditions, the process of loading cargo proteins seems to be selective.[26]

In gram-positive bacteria

[edit]In some Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, the accessory secretory system handles the export of highly repetitive adhesion glycoproteins.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lee JS, Jeremic A, Shin L, Cho WJ, Chen X, Jena BP (July 2012). "Neuronal porosome proteome: Molecular dynamics and architecture". Journal of Proteomics. 75 (13): 3952–62. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2012.05.017. PMC 4580231. PMID 22659300.

- ^ Anderson LL (2006). "Discovery of the 'porosome'; the universal secretory machinery in cells". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 10 (1): 126–31. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00294.x. PMC 3933105. PMID 16563225.

- ^ Nickel W, Seedorf M (2008). "Unconventional mechanisms of protein transport to the cell surface of eukaryotic cells". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 24: 287–308. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175320. PMID 18590485.

- ^ McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA (2003). "Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 19: 697–731. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140101. PMID 14570587.

- ^ Chirico WJ (October 2011). "Protein release through nonlethal oncotic pores as an alternative nonclassical secretory pathway". BMC Cell Biology. 12 46. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-12-46. PMC 3217904. PMID 22008609.

- ^ Wooldridge, K, ed. (2009). Bacterial Secreted Proteins: Secretory Mechanisms and Role in Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-42-4.[page needed]

- ^ Boyd CD, Smith TJ, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Newell PD, Dufrêne YF, O'Toole GA (August 2014). "Structural features of the Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm adhesin LapA required for LapG-dependent cleavage, biofilm formation, and cell surface localization". Journal of Bacteriology. 196 (15): 2775–88. doi:10.1128/JB.01629-14. PMC 4135675. PMID 24837291.

- ^ Salyers, A. A. & Whitt, D. D. (2002). Bacterial Pathogenesis: A Molecular Approach, 2nd ed., Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. ISBN 1-55581-171-X[page needed]

- ^ Hatakeyama M, Higashi H (December 2005). "Helicobacter pylori CagA: a new paradigm for bacterial carcinogenesis". Cancer Science. 96 (12): 835–43. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00130.x. PMC 11159386. PMID 16367902. S2CID 5721063.

- ^ Cascales E, Christie PJ (November 2003). "The versatile bacterial type IV secretion systems". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 1 (2): 137–49. doi:10.1038/nrmicro753. PMC 3873781. PMID 15035043.

- ^ Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V, Jakubowski S, Cascales E (2005). "Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems". Annual Review of Microbiology. 59: 451–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. PMC 3872966. PMID 16153176.

- ^ Christie PJ (November 2004). "Type IV secretion: the Agrobacterium VirB/D4 and related conjugation systems". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1694 (1–3): 219–34. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.013. PMC 4845649. PMID 15546668.

- ^ a b Yeo HJ, Yuan Q, Beck MR, Baron C, Waksman G (December 2003). "Structural and functional characterization of the VirB5 protein from the type IV secretion system encoded by the conjugative plasmid pKM101". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (26): 15947–52. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10015947Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.2535211100. JSTOR 3149111. PMC 307673. PMID 14673074.

- ^ Lawley TD, Klimke WA, Gubbins MJ, Frost LS (July 2003). "F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 224 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0. PMID 12855161.

- ^ Rikihisa Y, Lin M, Niu H (September 2010). "Type IV secretion in the obligatory intracellular bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum". Cellular Microbiology. 12 (9): 1213–21. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01500.x. PMC 3598623. PMID 20670295.

- ^ Thanassi DG, Stathopoulos C, Karkal A, Li H (2005). "Protein secretion in the absence of ATP: the autotransporter, two-partner secretion and chaperone/usher pathways of gram-negative bacteria (review)". Molecular Membrane Biology. 22 (1–2): 63–72. doi:10.1080/09687860500063290. PMID 16092525. S2CID 2708575.

- ^ Gerlach RG, Hensel M (October 2007). "Protein secretion systems and adhesins: the molecular armory of Gram-negative pathogens". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 297 (6): 401–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.03.017. PMID 17482513.

- ^ Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ (January 2006). "Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (5): 1528–33. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1528P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510322103. JSTOR 30048406. PMC 1345711. PMID 16432199.

- ^ Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, Goodman AL, Joachimiak G, Ordoñez CL, Lory S, Walz T, Joachimiak A, Mekalanos JJ (June 2006). "A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus". Science. 312 (5779): 1526–30. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1526M. doi:10.1126/science.1128393. PMC 2800167. PMID 16763151.

- ^ Bingle LE, Bailey CM, Pallen MJ (February 2008). "Type VI secretion: a beginner's guide" (PDF). Current Opinion in Microbiology. 11 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.006. PMID 18289922.

- ^ Cascales E (August 2008). "The type VI secretion toolkit". EMBO Reports. 9 (8): 735–41. doi:10.1038/embor.2008.131. PMC 2515208. PMID 18617888.

- ^ Schwarz S, Hood RD, Mougous JD (December 2010). "What is type VI secretion doing in all those bugs?". Trends in Microbiology. 18 (12): 531–7. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2010.09.001. PMC 2991376. PMID 20961764.

- ^ Coulthurst SJ (2013). "The Type VI secretion system - a widespread and versatile cell targeting system". Research in Microbiology. 164 (6): 640–54. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.017. PMID 23542428.

- ^ Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD (2012). "Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system". Annual Review of Microbiology. 66: 453–72. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619. PMC 3595004. PMID 22746332.

- ^ Kuehn MJ, Kesty NC (November 2005). "Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host–pathogen interaction". Genes & Development. 19 (22): 2645–55. doi:10.1101/gad.1299905. PMID 16291643.

- ^ McBroom AJ, Kuehn MJ (January 2007). "Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response". Molecular Microbiology. 63 (2): 545–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05522.x. PMC 1868505. PMID 17163978.

- ^ Z. Esna Ashari, N. Dasgupta, K. Brayton & S. Broschat, “An optimal set of features for predicting type IV secretion system effector proteins for a subset of species based on a multi-level feature selection approach”, PLOS ONE Journal, 2018, 13, e0197041. (doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197041.)

Further reading

[edit]- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P, eds. (2002). "Search: Secretion". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- White D (2000). The Physiology and Biochemistry of Prokaryotes (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512579-5.

- Avon D. "Home page". Cells alive!.

External links

[edit]- Secretions at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- T5SS / Autotransporter illustration at Uni Münster