Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Appressorium

View on Wikipedia

An appressorium is a specialized cell typical of many fungal plant pathogens that is used to infect host plants. It is a flattened, hyphal "pressing" organ, from which a minute infection peg grows and enters the host, using turgor pressure capable of punching through even Mylar.[1][2]

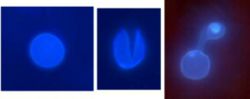

Following spore attachment and germination on the host surface, the emerging germ tube perceives physical cues such as surface hardness and hydrophobicity, as well as chemical signals including wax monomers that trigger appressorium formation. Appressorium formation begins when the tip of the germ tube ceases polar growth, hooks, and begins to swell. The contents of the spore are then mobilized into the developing appressorium, a septum develops at the neck of the appressorium, and the germ tube and spore collapse and die. As the appressorium matures, it becomes firmly attached to the plant surface and a dense layer of melanin is laid down in the appressorium wall, except across a pore at the plant interface. Turgor pressure increases inside the appressorium and a penetration hypha emerges at the pore, which is driven through the plant cuticle into the underlying epidermal cells. The osmotic pressure exerted by the appressorium can reach up to 8 MPa, which allows it to puncture the plant cuticle.[3] This pressure is achievable due to a melanin-pigmented cell wall which is impermeable to compounds larger than water molecules, so the highly-concentrated ions cannot escape from it.[4]

Formation

[edit]The attachment of a fungal spore on the surface of the host plant is the first critical step of infection. Once the spore is hydrated, an adhesive mucilage is released from its tip.[5] During germination, mucilaginous substances continue to be extruded at the tips of the germ tube, which are essential for germ tube attachment and appressorium formation.[6] Spore adhesion and appressorium formation is inhibited by hydrolytic enzymes such as α-mannosidase, α-glucosidase, and protease, suggesting that the adhesive materials are composed of glycoproteins.[6][7] Germination is also inhibited at high spore concentrations, which might be due to a lipophilic self inhibitor. Self inhibition can be overcome by hydrophobic wax from rice leaf.[8]

In response to surface signals, the germ tube tip undergoes a cell differentiation process to form a specialized infection structure, the appressorium. Frank B. (1883), in 'Ueber einige neue und weniger bekannte Pflanzenkrankheiten', coined the name "appressorium" for the adhesion body formed by the bean pathogen Gloeosporium lindemuthianum on the host surface.[9]

Appressorium development involves a number of steps: nuclear division, first septum formation, germling emergence, tip swelling and second septum formation. Mitosis first occurs soon after surface attachment, and a nucleus from the second round of mitosis during tip swelling migrates into the hooked cell before septum formation. A mature appressorium normally contains a single nucleus.[2][10] The outside plasma membrane of the mature appressorium is covered by a melanin layer except at the region in contact with the substratum, where the penetration peg, a specialized hypha that penetrates the tissue surface, develops.[2][11] Cellular glycerol concentration sharply increases during spore germination, but it rapidly decreases at the point of appressorium initiation, and then gradually increases again during appressorium maturation. This glycerol accumulation generates high turgor pressure in the appressorium, and melanin is necessary for maintaining the glycerol gradient across the appressorium cell wall.[12]

Initiation

[edit]Appressoria are induced in response to physical cues including surface hardness and hydrophobicity, as well as chemical signals of aldehydes[13] exogenous cAMP, ethylene, the host's ripening hormone and the plant cutin monomer hexadecanoic acid.[14][15] Long chain fatty acids and the tripeptide sequence Arg-Gly-Asp inhibit appressorium induction.[16][17]

Rust fungi only form appressoria at stomata, since they can only infect plants through these pores. Other fungi tend to form appressoria over anticlinal cell walls, and some form them at any location.[18][19]

References

[edit]- ^ Howard RJ, Ferrari MA, Roach DH, Money NP (1991). "Penetration of hard substrates by a fungus employing enormous turgor pressures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 88 (24): 11281–84. Bibcode:1991PNAS...8811281H. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.24.11281. PMC 53118. PMID 1837147.

- ^ a b c Howard RJ, Valent B (1996). "Breaking and entering: host penetration by the fungal rice blast pathogen Magnaporthe grisea". Annual Review of Microbiology. 50: 491–512. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.491. PMID 8905089.

- ^ Fitopatologia. T. 1, Podstawy fitopatologii. Selim Kryczyński, Zbigniew Weber, Barbara Gołębniak. Poznań: Powszechne Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Leśne. 2010. ISBN 978-83-09-01063-0. OCLC 802060485.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Howard, Richard J.; Ferrari, Margaret A. (1989-12-01). "Role of melanin in appressorium function". Experimental Mycology. 13 (4): 403–418. doi:10.1016/0147-5975(89)90036-4. ISSN 0147-5975.

- ^ Braun EJ, Howard RJ (1994). "Adhesion of fungal spores and germlings to host-plant surfaces". Protoplasma. 181 (1–4): 202–12. doi:10.1007/BF01666396. S2CID 35667834.

- ^ a b Xiao JZ, Ohsima A, Kamakura T, Ishiyama T, Yamaguchi I (1994). "Extracellular glycoprotein(s) associated with cellular differentiation in Magnaporthe grisea" (PDF). Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 7 (5): 639–44. doi:10.1094/MPMI-7-0639.

- ^ Ohtake M, Yamamoto H, Uchiyama T (1999). "Influences of metabolic inhibitors and hydrolytic enzymes on the adhesion of appressoria of Pyricularia oryzae to wax-coated cover-glasses" (PDF). Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 63 (6): 978–82. doi:10.1271/bbb.63.978. PMID 27389332.

- ^ Hegde Y; Kolattukudy PE (1997). "Cuticular waxes relieve self-inhibition of germination and appressorium formation by the conidia of Magnaporthe grisea". Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 51 (2): 75–84. doi:10.1006/pmpp.1997.0105.

- ^ Deising HB, Werner S, Wernitz M (2000). "The role of fungal appressoria in plant infection". Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur. 2 (13): 1631–41. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01319-8. PMID 11113382.

- ^ Shaw BD, Kuo KC, Hoch HC (1998). "Germination and appressorium development of Phyllosticta ampelicida pycnidiospores". Mycologia. 90 (2): 258–68. doi:10.2307/3761301. JSTOR 3761301.

- ^ Bourett TM, Howard RJ (1990). "In vitro development of penetration structures in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea". Canadian Journal of Botany. 68 (2): 329–42. doi:10.1139/b90-044.

- ^ deJong JC, McCormack BJ, Smirnoff N, Talbot NJ (1997). "Glycerol generates turgor in rice blast". Nature. 389 (6648): 244–5. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..244D. doi:10.1038/38418. S2CID 205026525.

- ^ Zhu, M., et al. (2017). Very-long-chain aldehydes induce appressorium formation in ascospores of the wheat powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis. Fungal biology 121(8): 716-728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2017.05.003

- ^ Flaishman MA, Kolattukudy PE (1994). "Timing of fungal invasion using host's ripening hormone as a signal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (14): 6579–83. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6579F. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.14.6579. PMC 44246. PMID 11607484.

- ^ Gilbert RD, Johnson AM, Dean RA (1996). "Chemical signals responsible for appressorium formation in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea". Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 48 (5): 335–46. doi:10.1006/pmpp.1996.0027.

- ^ Lee YH, Dean RA (1993). "cAMP regulates infection structure formation in the plant-pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea" (PDF). Plant Cell. 5 (6): 693–700. doi:10.2307/3869811. JSTOR 3869811. PMC 160306. PMID 12271080.

- ^ Correa A, Staples RC, Hoch HC (1996). "Inhibition of thigmostimulated cell differentiation with RGD-peptides in Uromyces germlings". Protoplasma. 194 (1–2): 91–102. doi:10.1007/BF01273171. S2CID 8417737.

- ^ Hoch, H. C.; Staples, R. C. (1987). "Structural and Chemical Changes Among the Rust Fungi During Appressorium Development". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 25: 231–247. doi:10.1146/annurev.py.25.090187.001311.

- ^ Dean, R. A. (1997). "Signal Pathways and Appressorium Morphogenesis". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 35: 211–234. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.211. PMID 15012522.

Appressorium

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Definition

An appressorium is a specialized, flattened and swollen cell developed at the tip of a germ tube or hypha by many plant-pathogenic fungi, enabling adhesion to the host surface and subsequent penetration of tough barriers such as the plant cuticle.[4] This structure is characteristic of pathogens in phyla like Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, including prominent examples such as Magnaporthe oryzae (causal agent of rice blast) and various rust fungi.[1] Unlike general propagules like conidia or vegetative hyphae, the appressorium is infection-specific, forming only under conditions conducive to host colonization and differentiating into a rigid, often melanized organ for targeted invasion.[5] The primary function of the appressorium is to facilitate host tissue invasion by mechanically breaching the cuticle, often through the emergence of a narrow penetration peg that exerts focused pressure.[4] This process is essential for establishing infection in foliar pathogens, where the structure adheres tightly via an extracellular matrix and generates sufficient force—typically involving turgor pressure—to rupture or deform the host's protective layers without relying solely on enzymatic degradation.[5] In this way, appressoria represent a key adaptation for overcoming physical defenses in plants, distinguishing pathogenic fungi from saprophytic or non-invasive species.[1] The term "appressorium" was first introduced in the late 19th century by Albert Bernhard Frank in 1883, who described it as "spore-like organs" in the anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, highlighting its role in adhesion and penetration.[4] Early observations in rust fungi, such as those studied by Heinrich Anton de Bary in the 1860s–1880s, laid groundwork for understanding infection structures in biotrophic pathogens, though the specific nomenclature and detailed morphology were formalized later.[6] These foundational descriptions underscored the appressorium's evolutionary significance in fungal phytopathology.[1]Morphological Features

The appressorium is characteristically a dome- or lobed-shaped swelling that forms at the tip of the germ tube in plant-pathogenic fungi, typically measuring 5-20 μm in diameter.[1] For instance, in Magnaporthe oryzae, the appressorium adopts a globose, dome-like morphology with a diameter of 10-15 μm.[1] In Colletotrichum species, it often appears oval to lobose, contributing to its specialized role in host attachment.[7] Adhesion to the host surface is facilitated by attachment structures such as mucilage or adhesive pads, which consist of an extracellular matrix rich in glycoproteins, hydrophobins, chitosan, and lipids.[1] These structures, exemplified by the spore-tip mucilage in M. oryzae and Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, ensure firm contact with hydrophobic or hydrophilic plant surfaces.[7][1] Internally, the appressorium is often delimited by a septum that separates it from the germ tube and conidium, a feature observed in both hyaline and melanized types across various fungi.[1] This septation, as seen in M. oryzae and Colletotrichum truncatum, maintains structural integrity as a single-celled compartment.[1] The cell wall of the appressorium is composed primarily of chitin and β-1,3-glucans, which provide essential rigidity for mechanical function.[7] In species like M. oryzae and Colletotrichum spp., this composition supports the structure's durability.[1] Melanin pigmentation, present in some appressoria such as those of Pyricularia oryzae, forms a layer between the cell wall and plasma membrane to aid pressure containment.[7]Development and Formation

Initiation Triggers

The initiation of appressorium development in pathogenic fungi, such as Magnaporthe oryzae and Colletotrichum species, is primarily triggered by physical cues from the host surface sensed at the tip of the germ tube emerging from germinated spores.[8] Surface hydrophobicity, characterized by water contact angles greater than 90°, is a key signal that induces germ tube differentiation into appressoria, as demonstrated by high formation rates on hydrophobic materials like Teflon compared to hydrophilic surfaces. Topography and hardness further modulate this response; ridges or uneven surfaces alone do not trigger formation without hydrophobicity, but hard, rigid substrates mimicking plant cuticles promote appressorium initiation by providing mechanical resistance cues detected via mechanosensors at the germ tube apex.[8][9] Chemical signals derived from the host plant also play a critical role in stimulating appressorium formation. Cutin monomers, such as 16-hydroxypalmitic acid, and wax components like 1,16-hexadecanediol, act as potent inducers by binding to fungal receptors, even in the absence of physical cues in some strains.[10] Plant volatiles, including ethylene, serve as ripening-associated signals that accelerate spore germination and appressorium development in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and C. musae, with concentrations as low as 1 µl/L triggering up to six appressoria per spore on climacteric fruits like tomato and banana.[11] These chemical cues are particularly important for synchronizing fungal infection with host susceptibility stages. Upon perception of these external signals, intracellular transduction pathways rapidly convert sensory inputs into developmental responses. The cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling cascade, activated by adenylate cyclase Mac1 and modulated by G-protein-coupled receptors like Pth11, promotes germ tube swelling and appressorium morphogenesis through protein kinase A-mediated actin reorganization. Recent studies have shown that GATA-dependent glutaminolysis suppresses TOR inhibition of cAMP/PKA signaling to drive appressorium formation.[12] Concurrently, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway, involving the Pmk1/Mps1 kinase and upstream MAPKKKs Mst11 and Mst7, integrates hydrophobic and chemical cues to regulate gene expression essential for differentiation, with scaffold protein Mst50 ensuring pathway specificity. Additional regulators, such as MoRgs3, integrate intracellular reactive oxygen species perception with cAMP signaling.[13] Ras GTPases act upstream, linking surface perception to both cAMP and MAP kinase activation.[8] Timing of appressorium initiation varies by fungal species and cue strength but typically occurs rapidly, within 1-4 hours after spore germination and germ tube extension of 10-15 µm, leading to cessation of linear growth as an early response.[8] In M. oryzae, strong hydrophobic signals can initiate formation in under 1 hour, while chemical inducers like cutin monomers extend this window slightly for enhanced penetration readiness.[10] This swift transduction ensures efficient host invasion during favorable conditions.Formation Process

Following initiation by host surface cues such as hydrophobicity, the appressorium formation process in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae proceeds through a series of coordinated cellular and biochemical events. The germ tube, which emerges from the conidial germ pore, initially undergoes polar extension before its tip ceases linear growth, hooks, and begins to swell, forming the nascent appressorium dome. This swelling is driven by the mobilization of cytoplasmic contents from the conidium, where autophagy degrades stored reserves like glycogen and lipids, transferring nutrients and organelles to fuel appressorium differentiation; as a result, the conidium and germ tube collapse and become non-viable.[14][15][2] A critical early step involves septum formation at the base of the developing appressorium, which isolates its cytoplasm from the degenerating germ tube and conidium. This septum, often reinforced by a septin ring composed of proteins such as Sep3, Sep4, Sep5, and Sep6, establishes structural compartmentalization and scaffolds cytoskeletal elements like actin for subsequent polarization. Septum development typically occurs within the first 4–7 hours post-germination, marking the transition to a committed infection structure.[15][2][14] As the appressorium matures, melanin biosynthesis and deposition occur in the inner cell wall, providing osmotic impermeability and mechanical strength essential for pressure buildup. The dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin pathway, involving genes like ALB1 and BUF1, polymerizes melanin pigments that impregnate the chitin-chitosan matrix, except at the pore-like penetration site where the wall remains unmelanized to facilitate targeted host entry. This selective deposition begins around 7–12 hours and is tightly linked to cell cycle progression, particularly G2/M phases, ensuring wall rigidity without compromising functionality.[14][15][2] During the final maturation phase, up to 24 hours, osmolytes such as glycerol accumulate intracellularly to generate the hydrostatic pressure required for infection. Glycerol synthesis is upregulated via pathways involving trehalose breakdown and lipid mobilization, with concentrations reaching levels that yield up to 8 MPa of turgor; this process is regulated by signaling cascades including cAMP/PKA and MAPK modules, which coordinate metabolic shifts and prevent premature penetration. By 24 hours, the melanized appressorium is fully mature and poised for host invasion.[14][15][2]Mechanism of Penetration

Turgor Pressure Generation

Turgor pressure in the appressorium is generated through osmotic accumulation of compatible solutes, primarily glycerol and other polyols, which create an osmotic gradient driving water influx into the cell. In pathogenic fungi such as Magnaporthe oryzae, these solutes are synthesized during appressorium maturation from storage carbohydrates via glycolysis, where dihydroxyacetone phosphate—a glycolytic intermediate—is converted to glycerol-3-phosphate and then reduced to glycerol by NAD+-dependent glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. This process results in intracellular glycerol concentrations reaching up to 3 M, far exceeding external levels and enabling substantial water entry while maintaining cell integrity.[16] The cell wall of the appressorium, reinforced by a layer of dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin, serves as an impermeable barrier that prevents the efflux of these osmotically active polyols, thereby sustaining the hydrostatic pressure required for penetration.[2] Melanin deposition reduces wall porosity, confining solutes to the cytoplasm and allowing turgor pressures of 0.5–8 MPa to build, equivalent to forces capable of breaching plant cuticles.[17] Without melanin, as seen in mutants defective in its biosynthesis, polyol retention fails, leading to significantly reduced turgor and impaired infection.[18] The biophysical basis of this turgor follows the osmotic pressure relation, approximated aswhere is turgor pressure, is the gas constant, is absolute temperature, and is the difference in internal and external solute concentrations (in osmoles per liter).[19] This equation highlights how the steep osmotic gradient, driven by polyol accumulation, translates into mechanical force within the melanized appressorium. Experimental quantification of appressorial turgor typically employs incipient cytorrhysis assays, where appressoria are exposed to solutions of varying osmotic concentrations (e.g., glycerol or polyethylene glycol), and the external concentration causing 50% cell collapse corresponds to the internal turgor. This technique, pioneered in studies of M. oryzae, has measured pressures up to 5.4 MPa, with refinements in later work extending estimates to 8 MPa. Complementary methods, such as micropressure probes inserted into the appressorium, directly record turgor but are technically challenging due to the structure's small size (∼10 μm diameter) and rigidity.[20] These approaches confirm the role of osmotic solute dynamics in achieving the extraordinary pressures observed.[16]

Penetration Peg and Host Invasion

The penetration peg emerges from an unmelanized pore at the base of the mature appressorium, marking the initiation of host tissue invasion.[21] In the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae, this peg forms as a narrow hyphal extension, typically 0.8–0.9 μm in diameter, following cytoskeletal reorganization involving septin GTPases that direct polar growth toward the host surface.[22] Propelled by turgor pressure generated within the appressorium, the peg mechanically punctures the plant cuticle and underlying epidermal cell wall, exploiting the structural weakness at the pore site.[23] Once the cuticle is breached, the penetration peg advances into the epidermal cells, transitioning from a pointed hypha to bulbous, branched invasive hyphae that facilitate biotrophic colonization.[24] This invasive growth occurs intracellularly, allowing the fungus to spread synchronously to adjacent cells while suppressing host defenses through effector secretion via the peg.[25] Enzymatic assistance plays a complementary role, with cutinases—such as Cut2 in M. oryzae—hydrolyzing cutin esters to locally soften the hydrophobic cuticle barrier ahead of mechanical force.[26] Cellulases further degrade cellulose components of the cell wall, enhancing penetration efficiency without being solely responsible for entry.[26] Penetration success varies significantly due to host resistance factors, such as cuticle thickness, which can impede peg advancement and reduce invasion rates. For instance, in M. oryzae, wild-type strains achieve up to 93% penetration on rice leaves, whereas cutinase mutants exhibit only about 30% success, highlighting the interplay between enzymatic softening and mechanical puncture.[26] Thicker cuticles in resistant plant varieties further lower these rates by increasing the physical barrier to hyphal ingress.Types and Variations

In Different Fungal Groups

Appressoria in Ascomycetes, such as those formed by Pyricularia oryzae, the causal agent of rice blast disease, are typically unicellular but can develop a lobed or dome-shaped morphology to enhance adhesion and penetration force. These structures generate exceptionally high turgor pressure, reaching up to 8 MPa, primarily through the accumulation of glycerol as an osmotic solute, which is facilitated by melanization of the cell wall to maintain structural integrity and impermeability.[27][28] This high-pressure mechanism allows P. oryzae appressoria to breach the tough rice cuticle, initiating infection and leading to significant crop losses.[29] In Basidiomycetes, exemplified by rust fungi like Uromyces species, appressoria are unicellular and hyaline (non-pigmented), often positioning precisely over stomatal openings to facilitate entry into host tissues. For instance, in wheat rust pathogens closely related to Uromyces, these structures respond to topographical cues from stomatal guard cells, forming without extensive melanization and relying on moderate turgor combined with enzymatic softening of the host surface.[25] This stomatal-targeted formation contrasts with direct epidermal penetration in many Ascomycetes and enables biotrophic lifestyles in rust diseases of cereals.[1] Oomycetes, such as Phytophthora species responsible for downy mildews and rots, produce appressoria-like structures that arise from encysted zoospores rather than fungal hyphae, involving rapid cell wall deposition during encystment to form adhesive swellings. These structures lack melanization and are generally smaller, with penetration achieved through lower turgor pressure augmented by hydrolytic enzymes, as seen in Phytophthora infestans infections of potato.[25] In downy mildew pathogens like Peronospora, similar non-pigmented appressoria form over stomata post-encystment, emphasizing motility and adhesion over mechanical force. In water mold pathogens like Pythium, these are often sickle-shaped.[30] Key differences in appressoria across these groups reflect adaptations to host interaction strategies, as summarized below:| Fungal Group | Size | Melanization | Turgor Pressure Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycetes (e.g., P. oryzae) | Larger (10–15 µm) | Present | High (up to 8 MPa) |

| Basidiomycetes (e.g., Uromyces) | Variable, often smaller | Absent or low | Moderate (aided by enzymes) |

| Oomycetes (e.g., Phytophthora) | Smaller (~5–10 µm) | Absent | Low (enzyme-dependent) |