Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fatty acid

View on Wikipedia| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, from 4 to 28.[1] Fatty acids are a major component of the lipids (up to 70% by weight) in some species such as microalgae[2] but in some other organisms are not found in their standalone form, but instead exist as three main classes of esters: triglycerides, phospholipids, and cholesteryl esters. In any of these forms, fatty acids are both important dietary sources of fuel for animals and important structural components for cells.

History

[edit]The concept of fatty acid (acide gras) was introduced in 1813 by Michel Eugène Chevreul,[3][4][5] though he initially used some variant terms: graisse acide and acide huileux ("acid fat" and "oily acid").[6]

Types of fatty acids

[edit]

Fatty acids are classified in many ways: by length, by saturation vs unsaturation, by even vs odd carbon content, and by linear vs branched.

Length of fatty acids

[edit]- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of five or fewer carbons (e.g. butyric acid).[7]

- Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of 6 to 12[8] carbons, which can form medium-chain triglycerides.

- Long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of 13 to 21 carbons.[9]

- Very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of 22 or more carbons.

Saturated fatty acids

[edit]Saturated fatty acids have no C=C double bonds. They have the formula CH3(CH2)nCOOH, where n is some positive integer. An important saturated fatty acid is stearic acid (n = 16), which when neutralized with sodium hydroxide is the most common form of soap.

| Common name | Chemical structure | C :D [a] |

|---|---|---|

| Propionic acid | CH3CH2COOH | 3:0 |

| Butyric acid | CH3(CH2)2COOH | 4:0 |

| Caprylic acid | CH3(CH2)6COOH | 8:0 |

| Capric acid | CH3(CH2)8COOH | 10:0 |

| Lauric acid | CH3(CH2)10COOH | 12:0 |

| Myristic acid | CH3(CH2)12COOH | 14:0 |

| Palmitic acid | CH3(CH2)14COOH | 16:0 |

| Stearic acid | CH3(CH2)16COOH | 18:0 |

| Arachidic acid | CH3(CH2)18COOH | 20:0 |

| Behenic acid | CH3(CH2)20COOH | 22:0 |

| Lignoceric acid | CH3(CH2)22COOH | 24:0 |

| Cerotic acid | CH3(CH2)24COOH | 26:0 |

Unsaturated fatty acids

[edit]Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more C=C double bonds. The C=C double bonds can give either cis or trans isomers.

- cis

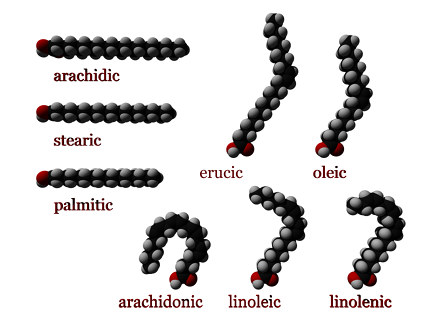

- A cis configuration means that the two hydrogen atoms adjacent to the double bond stick out on the same side of the chain. The rigidity of the double bond freezes its conformation and, in the case of the cis isomer, causes the chain to bend and restricts the conformational freedom of the fatty acid. The more double bonds the chain has in the cis configuration, the less flexibility it has. When a chain has many cis bonds, it becomes quite curved in its most accessible conformations. For example, oleic acid, with one double bond, has a "kink" in it, whereas linoleic acid, with two double bonds, has a more pronounced bend. α-Linolenic acid, with three double bonds, favors a hooked shape. The effect of this is that, in restricted environments, such as when fatty acids are part of a phospholipid in a lipid bilayer or triglycerides in lipid droplets, cis bonds limit the ability of fatty acids to be closely packed, and therefore can affect the melting temperature of the membrane or of the fat. Cis unsaturated fatty acids, however, increase cellular membrane fluidity, whereas trans unsaturated fatty acids do not.

- trans

- A trans configuration, by contrast, means that the adjacent two hydrogen atoms lie on opposite sides of the chain. As a result, they do not cause the chain to bend much, and their shape is similar to straight saturated fatty acids.

In most naturally occurring unsaturated fatty acids, each double bond has three (n−3), six (n−6), or nine (n−9) carbon atoms after it, and all double bonds have a cis configuration. Most fatty acids in the trans configuration (trans fats) are not found in nature and are the result of human processing (e.g., hydrogenation). Some trans fatty acids also occur naturally in the milk and meat of ruminants (such as cattle and sheep). They are produced, by fermentation, in the rumen of these animals. They are also found in dairy products from milk of ruminants, and may be also found in breast milk of women who obtained them from their diet.

The geometric differences between the various types of unsaturated fatty acids, as well as between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, play an important role in biological processes, and in the construction of biological structures (such as cell membranes).

| Common name | Chemical structure | Δx[b] | C:D[a] | IUPAC[10] | n−x[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omega−3: | |||||

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)3COOH | cis,cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ5,Δ8,Δ11,Δ14,Δ17 | 20:5 | 20:5(5,8,11,14,17) | n−3 |

| α-Linolenic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis,cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12,Δ15 | 18:3 | 18:3(9,12,15) | n−3 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)2COOH | cis,cis,cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ4,Δ7,Δ10,Δ13,Δ16,Δ19 | 22:6 | 22:6(4,7,10,13,16,19) | n−3 |

| Omega−6: | |||||

| Arachidonic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)3COOHNIST Archived 2009-03-04 at the Wayback Machine | cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ5Δ8,Δ11,Δ14 | 20:4 | 20:4(5,8,11,14) | n−6 |

| Linoleic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12 | 18:2 | 18:2(9,12) | n−6 |

| Linoelaidic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | trans,trans-Δ9,Δ12 | 18:2 | 18:2(9t,12t) | n−6 |

| Omega−9: | |||||

| Oleic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 18:1 | 18:1(9) | n−9 |

| Elaidic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | trans-Δ9 | 18:1 | 18:1(9t) | n−9 |

| Erucic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)11COOH | cis-Δ13 | 22:1 | 22:1(13) | n−9 |

| Omega−5, 7, and 10: | |||||

| Myristoleic acid | CH3(CH2)3CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 14:1 | 14:1(9) | n−5 |

| Palmitoleic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 16:1 | 16:1(9) | n−7 |

| Vaccenic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH(CH2)9COOH | trans-Δ11 | 18:1 | 18:1(11t) | n−7 |

| Sapienic acid | CH3(CH2)8CH=CH(CH2)4COOH | cis-Δ6 | 16:1 | 16:1(6) | n−10 |

Even- vs odd-chained fatty acids

[edit]Most fatty acids are even-chained, e.g. stearic (C18) and oleic (C18), meaning they are composed of an even number of carbon atoms. Some fatty acids have odd numbers of carbon atoms; they are referred to as odd-chained fatty acids (OCFA). The most common OCFA are the saturated C15 and C17 derivatives, pentadecanoic acid and heptadecanoic acid respectively, which are found in dairy products.[11][12] On a molecular level, OCFAs are biosynthesized and metabolized slightly differently from the even-chained relatives.

Branching

[edit]Most common fatty acids are straight-chain compounds, with no additional carbon atoms bonded as side groups to the main hydrocarbon chain. Branched-chain fatty acids contain one or more methyl groups bonded to the hydrocarbon chain.

Nomenclature

[edit]Carbon atom numbering

[edit]

Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of carbon atoms, with a carboxyl group (–COOH) at one end, and a methyl group (–CH3) at the other end.

The position of each carbon atom in the backbone of a fatty acid is usually indicated by counting from 1 at the −COOH end. Carbon number x is often abbreviated C-x (or sometimes Cx), with x = 1, 2, 3, etc. This is the numbering scheme recommended by the IUPAC.

Another convention uses letters of the Greek alphabet in sequence, starting with the first carbon after the carboxyl group. Thus carbon α (alpha) is C-2, carbon β (beta) is C-3, and so forth.

Although fatty acids can be of diverse lengths, in this second convention the last carbon in the chain is always labelled as ω (omega), which is the last letter in the Greek alphabet. A third numbering convention counts the carbons from that end, using the labels "ω", "ω−1", "ω−2". Alternatively, the label "ω−x" is written "n−x", where the "n" is meant to represent the number of carbons in the chain.[d]

In either numbering scheme, the position of a double bond in a fatty acid chain is always specified by giving the label of the carbon closest to the carboxyl end.[d] Thus, in an 18 carbon fatty acid, a double bond between C-12 (or ω−6) and C-13 (or ω−5) is said to be "at" position C-12 or ω−6. The IUPAC naming of the acid, such as "octadec-12-enoic acid" (or the more pronounceable variant "12-octadecanoic acid") is always based on the "C" numbering.

The notation Δx,y,... is traditionally used to specify a fatty acid with double bonds at positions x,y,.... (The capital Greek letter "Δ" (delta) corresponds to Roman "D", for Double bond). Thus, for example, the 20-carbon arachidonic acid is Δ5,8,11,14, meaning that it has double bonds between carbons 5 and 6, 8 and 9, 11 and 12, and 14 and 15.

In the context of human diet and fat metabolism, unsaturated fatty acids are often classified by the position of the double bond closest between to the ω carbon (only), even in the case of multiple double bonds such as the essential fatty acids. Thus linoleic acid (18 carbons, Δ9,12), γ-linolenic acid (18-carbon, Δ6,9,12), and arachidonic acid (20-carbon, Δ5,8,11,14) are all classified as "ω−6" fatty acids; meaning that their formula ends with –CH=CH–CH

2–CH

2–CH

2–CH

2–CH

3.

Fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms are called odd-chain fatty acids, whereas the rest are even-chain fatty acids. The difference is relevant to gluconeogenesis.

Naming of fatty acids

[edit]The following table describes the most common systems of naming fatty acids.

| Nomenclature | Examples | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Trivial | Palmitoleic acid | Trivial names (or common names) are non-systematic historical names, which are the most frequent naming system used in literature. Most common fatty acids have trivial names in addition to their systematic names (see below). These names frequently do not follow any pattern, but they are concise and often unambiguous. |

| Systematic | cis-9-octadec-9-enoic acid (9Z)-octadec-9-enoic acid |

Systematic names (or IUPAC names) derive from the standard IUPAC Rules for the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry, published in 1979,[13] along with a recommendation published specifically for lipids in 1977.[14] Carbon atom numbering begins from the carboxylic end of the molecule backbone. Double bonds are labelled with cis-/trans- notation or E-/Z- notation, where appropriate. This notation is generally more verbose than common nomenclature, but has the advantage of being more technically clear and descriptive. |

| Δx | cis-Δ9, cis-Δ12 octadecadienoic acid | In Δx (or delta-x) nomenclature, each double bond is indicated by Δx, where the double bond begins at the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from carboxylic end of the molecule backbone. Each double bond is preceded by a cis- or trans- prefix, indicating the configuration of the molecule around the bond. For example, linoleic acid is designated "cis-Δ9, cis-Δ12 octadecadienoic acid". This nomenclature has the advantage of being less verbose than systematic nomenclature, but is no more technically clear or descriptive.[citation needed] |

| n−x (or ω−x) |

n−3 (or ω−3) |

n−x (n minus x; also ω−x or omega−x) nomenclature both provides names for individual compounds and classifies them by their likely biosynthetic properties in animals. A double bond is located on the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from the methyl end of the molecule backbone. For example, α-linolenic acid is classified as a n−3 or omega−3 fatty acid, and so it is likely to share a biosynthetic pathway with other compounds of this type. The ω−x, omega−x, or "omega" notation is common in popular nutritional literature, but IUPAC has deprecated it in favor of n−x notation in technical documents.[13] The most commonly researched fatty acid biosynthetic pathways are n−3 and n−6. |

| Lipid numbers | 18:3 18:3n3 18:3, cis,cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12,Δ15 18:3(9,12,15) |

Lipid numbers take the form C:D,[a] where C is the number of carbon atoms in the fatty acid and D is the number of double bonds in the fatty acid. If D is more than one, the double bonds are assumed to be interrupted by CH 2 units, i.e., at intervals of 3 carbon atoms along the chain. For instance, α-linolenic acid is an 18:3 fatty acid and its three double bonds are located at positions Δ9, Δ12, and Δ15. This notation can be ambiguous, as some different fatty acids can have the same C:D numbers. Consequently, when ambiguity exists this notation is usually paired with either a Δx or n−x term.[13] For instance, although α-linolenic acid and γ-linolenic acid are both 18:3, they may be unambiguously described as 18:3n3 and 18:3n6 fatty acids, respectively. For the same purpose, IUPAC recommends using a list of double bond positions in parentheses, appended to the C:D notation.[10] For instance, IUPAC recommended notations for α- and γ-linolenic acid are 18:3(9,12,15) and 18:3(6,9,12), respectively. |

Free fatty acids

[edit]When circulating in the plasma (plasma fatty acids), not in their ester, fatty acids are known as non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) or free fatty acids (FFAs). FFAs are always bound to a transport protein, such as albumin.[15]

FFAs also form from triglyceride food oils and fats by hydrolysis, contributing to the characteristic rancid odor.[16] An analogous process happens in biodiesel with risk of part corrosion.

Production

[edit]Industrial

[edit]Fatty acids are usually produced industrially by the hydrolysis of triglycerides, with the removal of glycerol (see oleochemicals). Phospholipids represent another source. Some fatty acids are produced synthetically by hydrocarboxylation of alkenes.[17]

By animals

[edit]In animals, fatty acids are formed from carbohydrates predominantly in the liver, adipose tissue, and the mammary glands during lactation.[18]

Carbohydrates are converted into pyruvate by glycolysis as the first important step in the conversion of carbohydrates into fatty acids.[18] Pyruvate is then decarboxylated to form acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrion. However, this acetyl CoA needs to be transported into cytosol where the synthesis of fatty acids occurs. This cannot occur directly. To obtain cytosolic acetyl-CoA, citrate (produced by the condensation of acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate) is removed from the citric acid cycle and carried across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the cytosol.[18] There it is cleaved by ATP citrate lyase into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. The oxaloacetate is returned to the mitochondrion as malate.[19] The cytosolic acetyl-CoA is carboxylated by acetyl-CoA carboxylase into malonyl-CoA, the first committed step in the synthesis of fatty acids.[19][20]

Malonyl-CoA is then involved in a repeating series of reactions that lengthens the growing fatty acid chain by two carbons at a time. Almost all natural fatty acids, therefore, have even numbers of carbon atoms. When synthesis is complete the free fatty acids are nearly always combined with glycerol (three fatty acids to one glycerol molecule) to form triglycerides, the main storage form of fatty acids, and thus of energy in animals. However, fatty acids are also important components of the phospholipids that form the phospholipid bilayers out of which all the membranes of the cell are constructed (the cell wall, and the membranes that enclose all the organelles within the cells, such as the nucleus, the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi apparatus).[18]

The "uncombined fatty acids" or "free fatty acids" found in the circulation of animals come from the breakdown (or lipolysis) of stored triglycerides.[18][21] Because they are insoluble in water, these fatty acids are transported bound to plasma albumin. The levels of "free fatty acids" in the blood are limited by the availability of albumin binding sites. They can be taken up from the blood by all cells that have mitochondria (with the exception of the cells of the central nervous system). Fatty acids can only be broken down in mitochondria, by means of beta-oxidation followed by further combustion in the citric acid cycle to CO2 and water. Cells in the central nervous system, although they possess mitochondria, cannot take free fatty acids up from the blood, as the blood–brain barrier is impervious to most free fatty acids,[citation needed] excluding short-chain fatty acids and medium-chain fatty acids.[22][23] These cells have to manufacture their own fatty acids from carbohydrates, as described above, in order to produce and maintain the phospholipids of their cell membranes, and those of their organelles.[18]

Variation between animal species

[edit]Studies on the cell membranes of mammals and reptiles discovered that mammalian cell membranes are composed of a higher proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (DHA, omega−3 fatty acid) than reptiles.[24] Studies on bird fatty acid composition have noted similar proportions to mammals but with 1/3rd less omega−3 fatty acids as compared to omega−6 for a given body size.[25] This fatty acid composition results in a more fluid cell membrane but also one that is permeable to various ions (H+ & Na+), resulting in cell membranes that are more costly to maintain. This maintenance cost has been argued to be one of the key causes for the high metabolic rates and concomitant warm-bloodedness of mammals and birds.[24] However polyunsaturation of cell membranes may also occur in response to chronic cold temperatures as well. In fish increasingly cold environments lead to increasingly high cell membrane content of both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, to maintain greater membrane fluidity (and functionality) at the lower temperatures.[26][27]

Fatty acids in dietary fats

[edit]The following table gives the fatty acid, vitamin E and cholesterol composition of some common dietary fats.[28][29]

| Saturated | Monounsaturated | Polyunsaturated | Cholesterol | Vitamin E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/100g | g/100g | g/100g | mg/100g | mg/100g | |

| Animal fats | |||||

| Duck fat[30] | 33.2 | 49.3 | 12.9 | 100 | 2.70 |

| Lard[30] | 40.8 | 43.8 | 9.6 | 93 | 0.60 |

| Tallow[30] | 49.8 | 41.8 | 4.0 | 109 | 2.70 |

| Butter | 54.0 | 19.8 | 2.6 | 230 | 2.00 |

| Vegetable fats | |||||

| Coconut oil | 85.2 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 0 | .66 |

| Cocoa butter | 60.0 | 32.9 | 3.0 | 0 | 1.8 |

| Palm kernel oil | 81.5 | 11.4 | 1.6 | 0 | 3.80 |

| Palm oil | 45.3 | 41.6 | 8.3 | 0 | 33.12 |

| Cottonseed oil | 25.5 | 21.3 | 48.1 | 0 | 42.77 |

| Wheat germ oil | 18.8 | 15.9 | 60.7 | 0 | 136.65 |

| Soybean oil | 14.5 | 23.2 | 56.5 | 0 | 16.29 |

| Olive oil | 14.0 | 69.7 | 11.2 | 0 | 5.10 |

| Corn oil | 12.7 | 24.7 | 57.8 | 0 | 17.24 |

| Sunflower oil | 11.9 | 20.2 | 63.0 | 0 | 49.00 |

| Safflower oil | 10.2 | 12.6 | 72.1 | 0 | 40.68 |

| Hemp oil | 10 | 15 | 75 | 0 | 12.34 |

| Canola/Rapeseed oil | 5.3 | 64.3 | 24.8 | 0 | 22.21 |

Reactions of fatty acids

[edit]Fatty acids exhibit reactions like other carboxylic acids, i.e. they undergo esterification and acid-base reactions.

Transesterification

[edit]All fatty acids transesterify. Typically, transesterification is practiced in the conversion of fats to fatty acid methyl esters. These esters are used for biodiesel. They are also hydrogenated to give fatty alcohols. Even vinyl esters can be made by transesterification using vinyl acetate.[31]

Acid-base reactions

[edit]Fatty acids do not show a great variation in their acidities, as indicated by their respective pKa. Nonanoic acid, for example, has a pKa of 4.96, being only slightly weaker than acetic acid (4.76). As the chain length increases, the solubility of the fatty acids in water decreases, so that the longer-chain fatty acids have minimal effect on the pH of an aqueous solution. Near neutral pH, fatty acids exist at their conjugate bases, i.e. oleate, etc.

Solutions of fatty acids in ethanol can be titrated with sodium hydroxide solution using phenolphthalein as an indicator. This analysis is used to determine the free fatty acid content of fats; i.e., the proportion of the triglycerides that have been hydrolyzed.

Neutralization of fatty acids, like saponification, is a widely practiced route to metallic soaps.[32]

Hydrogenation and hardening

[edit]Hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids is widely practiced. Typical conditions involve 2.0–3.0 MPa of H2 pressure, 150 °C, and nickel supported on silica as a catalyst. This treatment affords saturated fatty acids. The extent of hydrogenation is indicated by the iodine number. Hydrogenated fatty acids are less prone toward rancidification. Since the saturated fatty acids are higher melting than the unsaturated precursors, the process is called hardening. Related technology is used to convert vegetable oils into margarine. The hydrogenation of triglycerides (vs fatty acids) is advantageous because the carboxylic acids degrade the nickel catalysts, affording nickel soaps. During partial hydrogenation, unsaturated fatty acids can be isomerized from cis to trans configuration.[17]

More forcing hydrogenation, i.e. using higher pressures of H2 and higher temperatures, converts fatty acids into fatty alcohols. Fatty alcohols are, however, more easily produced from simpler fatty acid esters, like the fatty acid methyl esters ("FAME"s).

Decarboxylation

[edit]Ketonic decarboxylation is a method useful for producing symmetrical ketones from carboxylic acids. The process involves reactions of the carboxylic acid with an inorganic base. Stearone is prepared by heating magnesium stearate.[33]

Chemistry of saturated vs unsaturated acids

[edit]The reactivity of saturated fatty acids is usually associated with the carboxylic acid or the adjacent methylene group By conversion to their acid chlorides, they can be converted to the symmetrical fatty ketone laurone (O=C(CnH(2n+1))2).[34] Treatment with sulfur trioxide gives the α-sulfonic acids.[35]

The reactivity of unsaturated fatty acids is often dominated by the site of unsaturation. These reactions are the basis of ozonolysis, hydrogenation, and the iodine number. Ozonolysis (degradation by ozone) is practiced in the production of azelaic acid ((CH2)7(CO2H)2) from oleic acid.[17]

Circulation

[edit]Digestion and intake

[edit]Short- and medium-chain fatty acids are absorbed directly into the blood via intestine capillaries and travel through the portal vein just as other absorbed nutrients do. However, long-chain fatty acids are not directly released into the intestinal capillaries. Instead they are absorbed into the fatty walls of the intestine villi and reassemble again into triglycerides. The triglycerides are coated with cholesterol and protein (protein coat) into a compound called a chylomicron.

From within the cell, the chylomicron is released into a lymphatic capillary called a lacteal, which merges into larger lymphatic vessels. It is transported via the lymphatic system and the thoracic duct up to a location near the heart (where the arteries and veins are larger). The thoracic duct empties the chylomicrons into the bloodstream via the left subclavian vein. At this point the chylomicrons can transport the triglycerides to tissues where they are stored or metabolized for energy.

Metabolism

[edit]Fatty acids are broken down to CO2 and water by the intra-cellular mitochondria through beta oxidation and the citric acid cycle. In the final step (oxidative phosphorylation), reactions with oxygen release a lot of energy, captured in the form of large quantities of ATP. Many cell types can use either glucose or fatty acids for this purpose, but fatty acids release more energy per gram. Fatty acids (provided either by ingestion or by drawing on triglycerides stored in fatty tissues) are distributed to cells to serve as a fuel for muscular contraction and general metabolism.

Essential fatty acids

[edit]Fatty acids that are required for good health but cannot be made in sufficient quantity from other substrates, and therefore must be obtained from food, are called essential fatty acids. There are two series of essential fatty acids: one has a double bond three carbon atoms away from the methyl end; the other has a double bond six carbon atoms away from the methyl end. Humans lack the ability to introduce double bonds in fatty acids beyond carbons 9 and 10, as counted from the carboxylic acid side.[36] Two essential fatty acids are linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). These fatty acids are widely distributed in plant oils. The human body has a limited ability to convert ALA into the longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids — eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which can also be obtained from fish. Omega−3 and omega−6 fatty acids are biosynthetic precursors to endocannabinoids with antinociceptive, anxiolytic, and neurogenic properties.[37]

Distribution

[edit]Blood fatty acids adopt distinct forms in different stages in the blood circulation. They are taken in through the intestine in chylomicrons, but also exist in very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) and low density lipoproteins (LDL) after processing in the liver. In addition, when released from adipocytes, fatty acids exist in the blood as free fatty acids.

It is proposed that the blend of fatty acids exuded by mammalian skin, together with lactic acid and pyruvic acid, is distinctive and enables animals with a keen sense of smell to differentiate individuals.[38]

Skin

[edit]The stratum corneum – the outermost layer of the epidermis – is composed of terminally differentiated and enucleated corneocytes within a lipid matrix.[39] Together with cholesterol and ceramides, free fatty acids form a water-impermeable barrier that prevents evaporative water loss.[39] Generally, the epidermal lipid matrix is composed of an equimolar mixture of ceramides (about 50% by weight), cholesterol (25%), and free fatty acids (15%).[39] Saturated fatty acids 16 and 18 carbons in length are the dominant types in the epidermis,[39][40] while unsaturated fatty acids and saturated fatty acids of various other lengths are also present.[39][40] The relative abundance of the different fatty acids in the epidermis is dependent on the body site the skin is covering.[40] There are also characteristic epidermal fatty acid alterations that occur in psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory conditions.[39][40]

Analysis

[edit]The chemical analysis of fatty acids in lipids typically begins with an interesterification step that breaks down their original esters (triglycerides, waxes, phospholipids etc.) and converts them to methyl esters, which are then separated by gas chromatography[41] or analyzed by gas chromatography and mid-infrared spectroscopy.

Separation of unsaturated isomers is possible by silver ion complemented thin-layer chromatography.[42] Other separation techniques include high-performance liquid chromatography (with short columns packed with silica gel with bonded phenylsulfonic acid groups whose hydrogen atoms have been exchanged for silver ions). The role of silver lies in its ability to form complexes with unsaturated compounds.

Industrial uses

[edit]Fatty acids are mainly used in the production of soap, both for cosmetic purposes and, in the case of metallic soaps, as lubricants. Fatty acids are also converted, via their methyl esters, to fatty alcohols and fatty amines, which are precursors to surfactants, detergents, and lubricants.[17] Other applications include their use as emulsifiers, texturizing agents, wetting agents, anti-foam agents, or stabilizing agents.[43]

Esters of fatty acids with simpler alcohols (such as methyl-, ethyl-, n-propyl-, isopropyl- and butyl esters) are used as emollients in cosmetics and other personal care products and as synthetic lubricants. Esters of fatty acids with more complex alcohols, such as sorbitol, ethylene glycol, diethylene glycol, and polyethylene glycol are consumed in food, or used for personal care and water treatment, or used as synthetic lubricants or fluids for metal working.

Fatty acids[44] and their derivatives like dimer acids[45] have also been used by scientists to prepare polyurethane coatings of bio-based or bio-derived coatings.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "C:D" is the numerical symbol: total amount of (C)arbon atoms of the fatty acid, and the number of (D)ouble (unsaturated) bonds in it; if D > 1 it is assumed that the double bonds are separated by one or more methylene bridge(s).

- ^ Each double bond in the fatty acid is indicated by Δx, where the double bond is located on the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from the carboxylic acid end.

- ^ In n minus x (also ω−x or omega-x) nomenclature a double bond of the fatty acid is located on the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from the terminal methyl carbon (designated as n or ω) toward the carbonyl carbon.

- ^ a b c A common mistake is to say that the last carbon is "ω−1".

Another common mistake is to say that the position of a bond in omega-notation is the number of the carbon closest to the END.

For double bonds, these two mistakes happen to compensate each other; so that a "ω−3" fatty acid indeed has the double bond between the 3rd and 4th carbons from the end, counting the methyl as 1.

However, for substitutions and other purposes, they don't: a hydroxyl "at ω−3" is on carbon 15 (4th from the end), not 16. See for example this article. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(75)90089-2

Note also that the "−" in the omega-notation is a minus sign, and "ω−3" should in principle be read "omega minus three". However, it is very common (especially in non-scientific literature) to write it "ω-3" (with a hyphen/dash) and read it as "omega-three". See for example Karen Dooley (2008), Omega-three fatty acids and diabetes.

- ^ Moss, G. P.; Smith, P. A. S.; Tavernier, D. (1997). "IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 67 (8–9). International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry: 1307–1375. doi:10.1351/pac199567081307. S2CID 95004254. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ Chen, Lin (2012). "Biodiesel production from algae oil high in free fatty acids by two-step catalytic conversion". Bioresource Technology. 111: 208–214. Bibcode:2012BiTec.111..208C. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.033. PMID 22401712.

- ^ Chevreul, M. E. (1813). "Sur plusieurs corps gras, et particulièrement sur leurs combinaisons avec les alcalis". Annales de Chimie. 88. Paris: H. Perronneau: 225–261 – via Gallica.

- ^ Chevreul, M. E. (1823). Recherches chimiques sur les corps gras d'origine animale. Paris: Levrault – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Leray, Claude (11 November 2017). "Chronological history of lipid science". Cyberlipid Center. Archived from the original on 2017-10-06.

- ^ Menten, P., ed. (2013). Dictionnaire de chimie: Une approche étymologique et historique. Bruxelles: De Boeck. ISBN 978-2-8041-8175-8.

- ^ Cifuentes, Alejandro, ed. (2013-03-18). "Microbial Metabolites in the Human Gut". Foodomics: Advanced Mass Spectrometry in Modern Food Science and Nutrition. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. ISBN 978-1-118-16945-2.

- ^ Roth, Karl S. (2013-12-19). "Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency". Medscape.

- ^ Beermann, C.; Jelinek, J.; Reinecker, T.; Hauenschild, A.; Boehm, G.; Klör, H.-U. (2003). "Short term effects of dietary medium-chain fatty acids and n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on the fat metabolism of healthy volunteers". Lipids in Health and Disease. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-2-10. PMC 317357. PMID 14622442.

- ^ a b "IUPAC Lipid nomenclature: Appendix A: names of and symbols for higher fatty acids". www.sbcs.qmul.ac.uk.

- ^ Pfeuffer, Maria; Jaudszus, Anke (2016). "Pentadecanoic and Heptadecanoic Acids: Multifaceted Odd-Chain Fatty Acids". Advances in Nutrition. 7 (4): 730–734. doi:10.3945/an.115.011387. PMC 4942867. PMID 27422507.

- ^ Smith, S. (1994). "The Animal Fatty Acid Synthase: One Gene, One Polypeptide, Seven Enzymes". The FASEB Journal. 8 (15): 1248–1259. doi:10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001737. PMID 8001737. S2CID 22853095.

- ^ a b c Rigaudy, J.; Klesney, S. P. (1979). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. Pergamon. ISBN 978-0-08-022369-8. OCLC 5008199.

- ^ "The Nomenclature of Lipids. Recommendations, 1976". European Journal of Biochemistry. 79 (1): 11–21. 1977. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11778.x.

- ^ Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier.

- ^ Mariod, Abdalbasit; Omer, Nuha; Al, El Mugdad; Mokhtar, Mohammed (2014-09-09). "Chemical Reactions Taken Place During deep-fat Frying and Their Products: A review". Sudan University of Science & Technology SUST Journal of Natural and Medical Sciences. Supplementary issue: 1–17.

- ^ a b c d Anneken, David J.; Both, Sabine; Christoph, Ralf; Fieg, Georg; Steinberner, Udo; Westfechtel, Alfred (2006). "Fatty Acids". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_245.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Stryer, Lubert (1995). "Fatty acid metabolism.". Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 603–628. ISBN 978-0-7167-2009-6.

- ^ a b Ferre, P.; Foufelle, F. (2007). "SREBP-1c Transcription Factor and Lipid Homeostasis: Clinical Perspective". Hormone Research. 68 (2): 72–82. doi:10.1159/000100426. PMID 17344645.

this process is outlined graphically in page 73

- ^ Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith G.; Pratt, Charlotte W. (2006). Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 978-0-471-21495-3.

- ^ Zechner, R.; Strauss, J. G.; Haemmerle, G.; Lass, A.; Zimmermann, R. (2005). "Lipolysis: pathway under construction". Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 16 (3): 333–340. doi:10.1097/01.mol.0000169354.20395.1c. PMID 15891395. S2CID 35349649.

- ^ Tsuji A (2005). "Small molecular drug transfer across the blood–brain barrier via carrier-mediated transport systems". NeuroRx. 2 (1): 54–62. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.1.54. PMC 539320. PMID 15717057.

Uptake of valproic acid was reduced in the presence of medium-chain fatty acids such as hexanoate, octanoate, and decanoate, but not propionate or butyrate, indicating that valproic acid is taken up into the brain via a transport system for medium-chain fatty acids, not short-chain fatty acids. ... Based on these reports, valproic acid is thought to be transported bidirectionally between blood and brain across the BBB via two distinct mechanisms, monocarboxylic acid-sensitive and medium-chain fatty acid-sensitive transporters, for efflux and uptake, respectively.

- ^ Vijay N, Morris ME (2014). "Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (10): 1487–98. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990462. PMC 4084603. PMID 23789956.

Monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) are known to mediate the transport of short chain monocarboxylates such as lactate, pyruvate and butyrate. ... MCT1 and MCT4 have also been associated with the transport of short chain fatty acids such as acetate and formate which are then metabolized in the astrocytes [78].

- ^ a b Hulbert AJ, Else PL (August 1999). "Membranes as possible pacemakers of metabolism". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 199 (3): 257–74. Bibcode:1999JThBi.199..257H. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1999.0955. PMID 10433891.

- ^ Hulbert AJ, Faulks S, Buttemer WA, Else PL (November 2002). "Acyl composition of muscle membranes varies with body size in birds". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 205 (Pt 22): 3561–9. Bibcode:2002JExpB.205.3561H. doi:10.1242/jeb.205.22.3561. PMID 12364409.

- ^ Hulbert AJ (July 2003). "Life, death and membrane bilayers". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (Pt 14): 2303–11. Bibcode:2003JExpB.206.2303H. doi:10.1242/jeb.00399. PMID 12796449.

- ^ Raynard RS, Cossins AR (May 1991). "Homeoviscous adaptation and thermal compensation of sodium pump of trout erythrocytes". The American Journal of Physiology. 260 (5 Pt 2): R916–24. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.5.R916. PMID 2035703. S2CID 24441498.

- ^ McCann; Widdowson; Food Standards Agency (1991). "Fats and Oils". The Composition of Foods. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ Altar, Ted. "More Than You Wanted To Know About Fats/Oils". Sundance Natural Foods. Archived from the original on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2006-08-31.

- ^ a b c "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference". U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ^ Swern, Daniel; Jordan, Jr, E. F. (1950). "Vinyl Laurate and Other Vinyl Esters". Organic Syntheses. 30: 106. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.030.0106.

- ^ Schumann, Klaus; Siekmann, Kurt (2000). "Soaps". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_247. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ A. G. Dobson and H. H. Hatt (1953). "Stearone". Organic Syntheses. 33: 84. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.033.0084.

- ^ J. C. Sauer (1951). "Laurone". Organic Syntheses. 31: 68. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.031.0068.

- ^ Weil, J. K.; Bistline, Jr., R. G.; Stirton, A. J. (1956). "α-Sulfopalmitic Acid". Organic Syntheses. 36: 83. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.036.0083.

- ^ Bolsover, Stephen R.; et al. (15 February 2004). Cell Biology: A Short Course. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 42ff. ISBN 978-0-471-46159-3.

- ^ Ramsden, Christopher E.; Zamora, Daisy; Makriyannis, Alexandros; Wood, JodiAnne T.; Mann, J. Douglas; Faurot, Keturah R.; MacIntosh, Beth A.; Majchrzak-Hong, Sharon F.; Gross, Jacklyn R. (August 2015). "Diet-induced changes in n-3 and n-6 derived endocannabinoids and reductions in headache pain and psychological distress". The Journal of Pain. 16 (8): 707–716. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.04.007. ISSN 1526-5900. PMC 4522350. PMID 25958314.

- ^ "Electronic Nose Created To Detect Skin Vapors". Science Daily. July 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Knox, Sophie; O'Boyle, Niamh M. (2021). "Skin lipids in health and disease: A review". Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 236 105055. doi:10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2021.105055. ISSN 0009-3084. PMID 33561467. S2CID 231864420.

- ^ a b c d Merleev, Alexander A.; Le, Stephanie T.; Alexanian, Claire; et al. (2022-08-22). "Biogeographic and disease-specific alterations in epidermal lipid composition and single-cell analysis of acral keratinocytes". JCI Insight. 7 (16) e159762. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.159762. ISSN 2379-3708. PMC 9462509. PMID 35900871.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Ormazabal M, Vallejo A, Olivares M, Navarro P, Etxebarria N, et al. (January 2015). "Optimization of supercritical fluid consecutive extractions of fatty acids and polyphenols from Vitis vinifera grape wastes". Journal of Food Science. 80 (1): E101-7. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12715. PMID 25471637.

- ^ Breuer, B.; Stuhlfauth, T.; Fock, H. P. (1987). "Separation of Fatty Acids or Methyl Esters Including Positional and Geometric Isomers by Alumina Argentation Thin-Layer Chromatography". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 25 (7): 302–6. doi:10.1093/chromsci/25.7.302. PMID 3611285.

- ^ "Fatty Acids: Building Blocks for Industry" (PDF). aciscience.org. American Cleaning Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-23. Retrieved 22 Apr 2018.

- ^ SD Rajput, VV Gite, PP Mahulikar, VR Thamke, KM Kodam, AS Kuwar, Renewable source based non-biodegradable polyurethane coatings from polyesteramide prepared in one-pot using oleic acid, Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 91, 1055–1063, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-014-2428-z

- ^ SD Rajput, PP Mahulikar, VV Gite, Biobased dimer fatty acid containing two pack polyurethane for wood finished coatings, Progress in Organic Coatings 77 (1), 38–46

External links

[edit]Fatty acid

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Discovery and Isolation

The early discovery of fatty acids traces back to the work of French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul in the early 19th century. In 1811, Chevreul began systematic investigations into the composition of soaps derived from animal fats, prompted by his mentor Nicolas-Louis Vauquelin. By acidifying soap solutions, he isolated crystalline substances that displayed acidic properties and could form salts with bases, leading him to coin the term "acides gras" (fatty acids) to describe these compounds extracted from natural fats.[4][5] His observations marked the first recognition of fatty acids as distinct chemical entities separable from the glycerol backbone of fats. Chevreul's experiments in the 1810s and 1820s focused on saponifying various animal and plant lipids to liberate the free fatty acids, followed by purification techniques such as recrystallization of their metal salts (e.g., barium or lead salts) to achieve separation based on solubility differences. From these efforts, he isolated and named several key fatty acids, including stearic acid from mutton fat in 1817, oleic acid from olive and pork fats around 1819, and margaric acid (later identified as a mixture) from various sources in 1816. These isolations revolutionized the understanding of fat chemistry, demonstrating that natural fats were esters of glycerol and these organic acids, and enabling practical applications in soap and candle production through a 1825 patent with Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac for stearic acid-based products.[6][4] Throughout the 19th century, refinements in experimental methods advanced the isolation of individual fatty acids from complex mixtures in animal tallows, plant oils, and other lipids. Saponification—boiling fats with alkali hydroxides to hydrolyze esters into glycerol and fatty acid salts—emerged as the foundational technique, with subsequent acidification yielding the free acids; this process, formalized by Chevreul, allowed scalable extraction from natural sources. Complementary advancements included fractional distillation of the freed acids under reduced pressure to separate them by boiling point differences, particularly effective for liquid unsaturated acids like oleic. These methods facilitated broader access to pure compounds for analysis and industry, with early applications in refining animal fats for margarine production by the mid-century.[7][6] Notable milestones in specific isolations during this period include palmitic acid, obtained in 1840 by French chemist Edmond Frémy through saponification of palm oil, highlighting the diversity of plant-derived fatty acids. Similarly, myristic acid was first isolated in 1841 by British chemist Lyon Playfair from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) butter via hydrolysis and crystallization. The carboxylic acid nature of these compounds was empirically confirmed through their salt-forming behavior, akin to known acids like acetic, and further validated in the 1840s by oxidation studies conducted by Justus von Liebig and contemporaries, which degraded the acids to carbon dioxide, water, and simpler carboxylates consistent with a -COOH functional group at one end of an aliphatic chain.[8][9][7]Key Milestones in Research and Classification

In 1929, George O. Burr and Mildred Burr demonstrated that rats on a fat-free diet developed severe symptoms, including growth retardation and skin lesions, which could only be alleviated by supplementing with specific unsaturated fats, thereby establishing linoleic acid (an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid) as an essential nutrient that mammals cannot synthesize de novo.[10] Their subsequent work in the early 1930s extended this finding to alpha-linolenic acid (an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid), confirming it as another essential fatty acid required for preventing deficiency symptoms like scaly skin and reproductive failure.[11] This breakthrough shifted the understanding of dietary fats from mere energy sources to vital components for membrane integrity and physiological function. During the 1950s, Eugene P. Kennedy and Albert L. Lehninger elucidated the mitochondrial beta-oxidation pathway, revealing how fatty acids are sequentially shortened by two-carbon units to generate acetyl-CoA for energy production via the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.[12] Their experiments with isolated rat liver mitochondria demonstrated that fatty acid oxidation is tightly coupled to ATP synthesis, providing a mechanistic link between lipid catabolism and cellular energy metabolism that explained the high caloric yield of fats.[13] This work built on earlier hypotheses and laid the foundation for studying metabolic disorders involving defective beta-oxidation. In the 1970s, Sune Bergström and Bengt I. Samuelsson identified eicosanoids, a class of bioactive lipids derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids like arachidonic acid, including prostaglandins that mediate inflammation, pain, and vascular regulation.[14] Their structural elucidation of these compounds, showing how they arise from enzymatic oxidation of C20 polyunsaturated fatty acids, highlighted their roles in physiological signaling and disease. This research earned them the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (shared with John R. Vane), transforming fatty acids from structural molecules into precursors of potent regulatory mediators.[15] In 2023, researchers at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) employed ozone-enabled mass spectrometry to identify 103 previously unknown unsaturated fatty acids in human plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and adipose tissue samples, effectively doubling the catalog of known human-derived unsaturated fatty acids.[16] This discovery revealed unexpected structural diversity, including branched and cyclic variants, and underscored the need for advanced lipidomics tools to map the full human lipidome, potentially aiding biomarker discovery for metabolic and neurological conditions.[17] From 2023 to 2025, studies have advanced the understanding of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids' roles in health maintenance, with a comprehensive MDPI review indicating that supplementation preserves muscle strength in older adults by modulating inflammation and supporting protein synthesis, showing small but significant effects in randomized trials.[18] Concurrently, research reported in ScienceDaily highlighted that higher circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids were associated with better lung function and slower decline in individuals with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), suggesting benefits for maintaining respiratory health.[19]Definition and Structure

Chemical Composition

Fatty acids are aliphatic carboxylic acids consisting of a hydrocarbon chain attached to a carboxyl group. The general formula for saturated fatty acids is , where , comprising a polar carboxylic acid head () and a nonpolar hydrocarbon tail.[20] Naturally occurring fatty acids typically feature unbranched carbon chains of 4 to 28 atoms in length, with even-numbered chains predominating due to their biosynthesis from successive two-carbon acetyl-CoA units.[21] At physiological pH, the carboxyl group () deprotonates to form a carboxylate anion (), as exemplified by stearate derived from stearic acid.[22] This combination of a charged, hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail renders fatty acids amphipathic.[23]Physical and Chemical Properties

Fatty acids display a range of physical states at room temperature that depend on their carbon chain length. Short-chain fatty acids containing 4 to 6 carbon atoms, such as butyric acid, exist as colorless liquids with melting points below 0°C; for example, butyric acid has a melting point of -7.9°C.[24] Medium-chain fatty acids with 8 to 12 carbons are typically oily liquids or waxy solids with low melting points, while long-chain fatty acids with 14 or more carbons are white solids; stearic acid, for instance, melts at 69.3°C.[25] These trends arise because longer chains enable greater van der Waals interactions, raising melting points progressively with chain length.[26] Regarding solubility, fatty acids are poorly soluble in water due to the hydrophobic nature of their nonpolar alkyl chains, which dominate over the polar carboxylic acid group, leading to insolubility for chains longer than about 10 carbons.[27] In contrast, they dissolve readily in nonpolar organic solvents like chloroform, ethanol, and ether, where the hydrocarbon tails interact favorably.[28] At higher concentrations in aqueous media, fatty acids can function as surfactants, self-assembling into micelles above their critical micelle concentration (CMC), which varies with chain length but typically falls in the millimolar range for medium- to long-chain acids.[29] Chemically, fatty acids behave as weak carboxylic acids with pKa values of approximately 4.5 to 5.0, rendering them weaker than simple carboxylic acids like acetic acid (pKa 4.76) because the extended alkyl chain exerts an electron-donating inductive effect that stabilizes the neutral form.[30][31] This acidity is described by the ionization equilibrium: where R represents the alkyl chain. Trends in density and viscosity are influenced by saturation level and chain length. Density generally decreases with unsaturation due to looser molecular packing from cis double bonds; for example, oleic acid (C18:1) has a density of 0.89 g/cm³ at 25°C (liquid), while saturated stearic acid (C18:0) has a density of 0.94 g/cm³ at 20°C (solid).[32] Viscosity follows a similar pattern, with unsaturated fatty acids showing reduced values compared to their saturated counterparts owing to decreased intermolecular forces.[33]Classification

By Carbon Chain Length

Fatty acids are classified by the length of their carbon chain, which influences their physical properties, metabolic pathways, and biological roles. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) contain 2 to 6 carbon atoms, medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) have 8 to 12 carbons, long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) range from 14 to 20 carbons, and very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) exceed 20 carbons.[34] This categorization highlights how chain length affects volatility, absorption rates, and incorporation into cellular structures. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), with 2 to 6 carbons, are volatile compounds primarily produced through microbial fermentation of dietary fibers in the gut. Acetic acid (C2:0), a key SCFA, is the main component of vinegar and contributes to its characteristic odor. Butyric acid (C4:0) is found in butter, where it constitutes about 4% of total fatty acids, and plays a role in gut health by serving as an energy source for colonocytes. These SCFAs are rapidly metabolized and influence host physiology, including immune modulation.[35][36][37] Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs), spanning 8 to 12 carbons, are distinguished by their rapid absorption and oxidation, bypassing the need for carnitine-dependent transport into mitochondria. Caprylic acid (C8:0), abundant in coconut oil, exemplifies MCFAs and is a primary component of medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oils used for quick energy provision, particularly in clinical nutrition for malabsorption disorders. MCFAs provide immediate energy due to their efficient hepatic metabolism.[38][39][40] Long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), with 14 to 20 carbons, predominate in human diets and form the structural backbone of most membrane lipids. Palmitic acid (C16:0) is the most abundant saturated LCFA in the diet, comprising about 55% of dietary saturated fats, and is integral to phospholipids in cell membranes. LCFAs are essential for energy storage and signaling but require specific transport mechanisms for utilization.[41][42] Very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), with more than 20 carbons, are enriched in specialized tissues such as skin and myelin sheaths, where they constitute significant portions of sphingomyelin and glycerophospholipids. Lignoceric acid (C24:0) is a prominent VLCFA in these structures, supporting barrier function and neural insulation. Accumulation of VLCFAs, including lignoceric acid, is a hallmark of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, a peroxisomal disorder leading to demyelination and adrenal insufficiency.[34][43] The length of the fatty acid chain critically impacts beta-oxidation, as different enzymes exhibit specificity for chain lengths: short- and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenases handle SCFAs and MCFAs, while long- and very long-chain variants process LCFAs and VLCFAs, primarily in peroxisomes for the latter. This enzymatic partitioning ensures efficient energy extraction tailored to chain size.[44][45]By Degree of Unsaturation

Fatty acids are classified by degree of unsaturation based on the number of carbon-carbon double bonds in their hydrocarbon chain, which influences their chemical reactivity, physical properties, and biological roles.[46] Saturated fatty acids contain no double bonds, making their chains fully hydrogenated and linear, which allows tight molecular packing and results in higher melting points compared to unsaturated counterparts.[47] A representative example is palmitic acid, denoted as 16:0, with 16 carbon atoms and zero double bonds, commonly found in animal fats and palm oil.[3] Monounsaturated fatty acids feature exactly one carbon-carbon double bond, typically in the cis configuration, introducing a kink in the chain that disrupts packing and lowers the melting point.[47] Oleic acid, or 18:1 Δ9 cis, exemplifies this class, comprising the majority of fatty acids in olive oil and contributing to its liquid state at room temperature.[48] Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) possess two or more double bonds, most often cis, leading to multiple kinks that further reduce packing efficiency and increase susceptibility to oxidation due to the reactive allylic positions adjacent to the double bonds.[49] Linoleic acid (18:2 Δ9,12), an omega-6 PUFA, and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3 Δ9,12,15), an omega-3 PUFA, illustrate this category, with the omega designation indicating the position of the first double bond from the methyl end of the chain.[3] The standard notation for fatty acids integrates chain length and unsaturation as "total carbons:number of double bonds" (e.g., 18:3 for ALA), often followed by double bond positions using the delta (Δ) system, which numbers from the carboxyl carbon, or the omega (ω) system from the methyl end; cis or trans isomerism is specified, as trans configurations promote straighter chains and better packing similar to saturated acids. This notation also links to chain length classification by specifying total carbons upfront. In 2023, researchers identified 103 previously unknown unsaturated fatty acids in human samples using ozonolysis-mass spectrometry, including novel polyunsaturated variants with unconventional double bond patterns, effectively doubling the cataloged diversity of these lipids in human plasma.[16]By Chain Configuration

Fatty acids are classified by chain configuration into even-chain, odd-chain, branched-chain, and cyclic forms, each arising from distinct biosynthetic pathways and serving specialized roles in organisms. Even-chain fatty acids, such as palmitic acid (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0), predominate in most biological systems and are synthesized via the fatty acid synthase complex using acetyl-CoA as the initial primer unit, followed by sequential additions of two-carbon malonyl-CoA units.[50] This process results in chains with an even number of carbon atoms, which form the structural backbone of membrane lipids and energy storage in animals, plants, and microorganisms.[51] In contrast, odd-chain fatty acids, exemplified by pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0), are less common and initiate synthesis with propionyl-CoA as the starter unit instead of acetyl-CoA, leading to chains terminating in an odd number of carbons after malonyl-CoA extensions.[51] These fatty acids occur in minor proportions in most tissues but are more prevalent in ruminant-derived products, such as milk fat and meat, due to microbial fermentation in the rumen that generates propionyl-CoA from dietary fiber and amino acids.[52] For instance, odd-chain fatty acids constitute about 4-6% of total fatty acids in bovine milk, reflecting the unique gut microbiome of ruminants.[53] Branched-chain fatty acids deviate from linear structures through methyl substitutions along the chain, with iso- and anteiso- forms being prominent in bacterial membranes. Iso-branched fatty acids, such as isopalmitic acid (14-methylpentadecanoic acid), feature a methyl group at the penultimate carbon, while anteiso- forms, like anteisoheptadecanoic acid (12-methylhexadecanoic acid), have the branch at the antepenultimate position; both are produced by bacteria using branched-chain acyl-CoA primers derived from amino acid catabolism to adjust membrane fluidity and packing.[54] In ruminants, these bacterial-derived branched chains transfer to host tissues, comprising up to 4% of milk fat.[55] Another notable branched fatty acid is phytanic acid (3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadecanoic acid), a highly branched saturated chain originating from the phytol tail of chlorophyll in plant forages, which ruminant microbes cleave and incorporate into lipids before absorption by the host.[55] Cyclic fatty acids represent a rare configuration, primarily featuring small ring structures integrated into the chain to enhance membrane stability. In bacteria, cyclopropane fatty acids incorporate a three-membered cyclopropane ring adjacent to the carboxyl group or at internal positions, formed post-synthesis by cyclopropane fatty acid synthases that transfer a methylene group from S-adenosylmethionine to an unsaturated precursor double bond.[56] These rings increase membrane rigidity and impermeability, allowing bacteria like Escherichia coli to maintain fluidity under environmental stresses such as low pH or desiccation without altering overall chain length or saturation.[57] Cyclic forms are scarce in eukaryotes but can arise in certain pathological conditions or from dietary sources. The metabolic implications of chain configuration extend beyond biosynthesis, influencing health outcomes in higher organisms. Odd-chain fatty acids, particularly C15:0 and C17:0, have been epidemiologically linked to reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, with higher circulating levels associated with 14-24% lower risk in prospective cohorts, potentially due to their roles in mitochondrial function and anti-inflammatory signaling.[58] Branched-chain fatty acids similarly modulate metabolism through altered lipid peroxidation and membrane dynamics.[54] Cyclic fatty acids, while primarily microbial, underscore how chain variations fine-tune biophysical properties like phase transitions in lipid bilayers.[59]Nomenclature

Systematic Naming Conventions

The systematic nomenclature of fatty acids follows the recommendations of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUPAC-IUBMB), which provide a structured approach based on the carbon chain length, degree of saturation, and configuration of double bonds.[60][61] For saturated fatty acids, the IUPAC name is derived from the corresponding alkane by replacing the "-ane" ending with "-anoic acid," where the carboxyl carbon is designated as carbon 1 (C-1). For example, the 18-carbon saturated fatty acid, commonly known as stearic acid, is systematically named octadecanoic acid.[60][62] Unsaturated fatty acids incorporate the suffix "-enoic acid" for one double bond (or "-dienoic acid" for two, and so on), with locants indicating the positions of the double bonds relative to C-1. The geometry of each double bond is specified using the E/Z designation, where Z corresponds to cis configuration and E to trans. A representative example is oleic acid, named (9Z)-octadec-9-enoic acid, indicating an 18-carbon chain with a cis double bond between carbons 9 and 10.[60][61] Double bond positions can also be denoted using delta (Δ) notation, which marks the lower-numbered carbon of the double bond counting from C-1 (e.g., Δ^9 for a double bond between C-9 and C-10), or omega (ω) notation, which counts from the methyl terminus (e.g., ω-3 for a double bond between C-3 and C-4 from the end). These notations are often used in shorthand alongside the systematic name, such as 18:2(Δ^9,Δ^{12}) for linoleic acid. For polyunsaturated acids with multiple double bonds, all positions and configurations are listed in ascending order, as in (9Z,12Z)-octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid for linoleic acid.[61][60] Trivial names for fatty acids often originate from their natural sources or historical isolation contexts. For instance, oleic acid derives its name from the Latin oleum, meaning oil, reflecting its abundance in olive and other plant oils. Similarly, arachidonic acid's name stems from arachidic acid, which was first isolated from peanut oil (Arachis hypogaea), with the prefix "arach-" adapted from the genus name.[32][63]Common Names and Shorthand Notations

Fatty acids are frequently referred to by common names derived from their primary natural sources, facilitating their identification in nutritional, biochemical, and industrial contexts. For instance, palmitic acid is named after palm oil, where it constitutes about 40% of the fatty acids; stearic acid derives from suet or animal fat, comprising 5-40% in ruminant fats; oleic acid from olive oil, its major constituent; and linoleic acid from linseed oil, present in virtually all seed oils.[64] These names provide a practical bridge to their systematic IUPAC equivalents, such as hexadecanoic acid for palmitic acid, as detailed in formal nomenclature conventions. In biochemical and nutritional literature, fatty acids are commonly denoted using shorthand notations that indicate chain length and degree of unsaturation. The general format is C_n:m, where n represents the number of carbon atoms and m the number of double bonds; for example, linoleic acid is abbreviated as 18:2, signifying 18 carbons and 2 double bonds. Double bond positions can be specified using Δ notation from the carboxyl end, such as 18:2(Δ9,12) for linoleic acid, or omitted when contextually clear. In biological systems, unsaturated fatty acids are typically assumed to have all-cis configurations unless otherwise stated. An alternative notation, particularly useful in nutrition and physiology, is the omega (ω) or n- system, which counts the position of the first double bond from the methyl (ω) end of the chain. This highlights the family classification, such as ω-3 for alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3 n-3), where the double bonds begin at the third carbon from the methyl terminus.[65] Similarly, linoleic acid is classified as 18:2 n-6. This system is essential for distinguishing essential fatty acid families like n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).[65] The following table summarizes major dietary fatty acids, categorized by saturation, with representative examples, their shorthand notations, and primary sources:| Category | Common Name | Shorthand Notation | Primary Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated (SFA) | Lauric acid | 12:0 | Coconut and palm kernel oils[64] |

| Saturated (SFA) | Palmitic acid | 16:0 | Palm oil, meat, dairy[64] |

| Saturated (SFA) | Stearic acid | 18:0 | Animal fats, cocoa butter[64] |

| Monounsaturated (MUFA) | Oleic acid | 18:1 n-9 | Olive oil, avocados, nuts[64] |

| Polyunsaturated (PUFA) | Linoleic acid | 18:2 n-6 | Seed oils (e.g., soybean, sunflower)[64] |

| Polyunsaturated (PUFA) | Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) | 18:3 n-3 | Flaxseed, chia seeds, walnuts[65] |

| Polyunsaturated (PUFA) | Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | 22:6 n-3 | Fatty fish (e.g., salmon), algae oils[65] |

Sources and Production

Biological Biosynthesis in Organisms

In eukaryotic organisms, the primary site of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis is the cytosol, where the multifunctional fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex catalyzes the iterative assembly of saturated fatty acids from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA precursors.[50] This type I FAS system operates through seven cycles of condensation, reduction, dehydration, and further reduction, starting with the priming of acetyl-CoA and incorporating seven malonyl-CoA units to yield palmitate (16:0), the most common product.[50] The overall reaction is: This process requires energy input from ATP for malonyl-CoA formation via acetyl-CoA carboxylase and reducing equivalents from NADPH, primarily generated by the pentose phosphate pathway.[50] Post-synthesis modifications occur in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or mitochondria, where elongases add two-carbon units from malonyl-CoA to the growing acyl chain, extending palmitate to longer fatty acids such as stearate (18:0).[66] These elongases, including ELOVL family members in animals and plants, facilitate the production of very-long-chain fatty acids essential for membrane structure and signaling.[66] Desaturation introduces double bonds via desaturase enzymes, which are oxygen-dependent and cytochrome b5-supported in eukaryotes. Plants possess Δ12 and Δ15 desaturases that enable synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like linoleic (18:2 ω-6) and α-linolenic (18:3 ω-3) acids from oleate and linoleate precursors, respectively, contributing to their high ω-3 content.[67] In contrast, animals lack Δ12 and Δ15 desaturases, limiting de novo PUFA production and rendering ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids essential in their diets.[67] Microbial fatty acid biosynthesis exhibits diversity, with bacteria employing a dissociated type II FAS system comprising individual enzymes in the cytosol to produce primarily straight-chain saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids.[68] Many bacteria, such as those in the genus Bacillus, generate branched-chain fatty acids (e.g., iso- and anteiso-forms) by initiating synthesis with branched primers like isobutyryl-CoA derived from valine catabolism, which enhances membrane fluidity under stress.[69] In microalgae like Schizochytrium species, a polyketide synthase-like PUFA synthase pathway enables efficient de novo production of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 ω-3), serving as a rich natural source for this long-chain ω-3 PUFA.[70] Species-specific variations further diversify fatty acid profiles; for instance, plants accumulate abundant ω-3 PUFAs due to their desaturase repertoire, supporting chloroplast membrane integrity.[67] In ruminants, rumen microbial biohydrogenation converts dietary unsaturated fatty acids to even-chain saturated forms, such as transforming linoleic acid to stearic acid via isomerization and hydrogenation by bacteria like Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, thereby altering the fatty acid composition absorbed in the small intestine.[71]Industrial Production Methods

Industrial production of fatty acids primarily involves the hydrolysis of triglycerides from natural fats and oils, yielding mixtures of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids alongside glycerol as a byproduct. Alkaline hydrolysis, or saponification, reacts triglycerides with sodium or potassium hydroxide under heat to form fatty acid salts (soaps) and glycerol; subsequent acidification liberates the free fatty acids. This method is commonly applied to vegetable sources like palm and soy oils, which provide high volumes of mixed fatty acids for oleochemical applications.[72][73] Acid hydrolysis, often catalyzed by sulfuric acid or conducted via high-pressure steam splitting, directly cleaves triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol without soap intermediates, achieving near-complete conversion (up to 99% yield) and is favored for large-scale production due to its efficiency.[74][75] Raw materials include animal tallow, rich in saturated fatty acids like palmitic and stearic acids, and vegetable oils such as soy and palm, which yield unsaturated fatty acids including oleic and linoleic acids. Following hydrolysis, fatty acids are purified via fractional distillation under vacuum, separating components by boiling point; for instance, tall oil fatty acids—comprising oleic and linoleic acids—are isolated from crude tall oil, a pine wood pulping byproduct, through this process.[76][77] Synthetic routes complement natural extraction for specialized fatty acids. Oxidation of hydrocarbons, such as n-paraffins with air or oxygen, produces linear fatty acids used in detergents, while the Koch reaction carbonylaates olefins with carbon monoxide and water under acidic conditions to yield branched carboxylic acids. Olefin metathesis, particularly cross-metathesis of natural unsaturated fatty acids with terminal alkenes, enables production of tailored polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) for nutraceuticals and polymers.[78][79] Recent advances emphasize sustainability, with enzymatic hydrolysis using immobilized lipases catalyzing triglyceride breakdown under mild conditions (40–60°C, pH 7–8), achieving 90–95% yields from waste oils while minimizing energy use and wastewater compared to chemical methods. The global fatty acids market is estimated at USD 33.8 billion in 2025 (as of September 2025), propelled by biofuel demand where fatty acids serve as precursors for biodiesel production.[80][81][82]Metabolism and Physiology

Digestion, Absorption, and Transport

The digestion of dietary fatty acids primarily occurs through the hydrolysis of triglycerides, the main form in which fats are ingested. In the oral cavity and stomach, lingual and gastric lipases initiate the process by partially hydrolyzing triglycerides into diglycerides and free fatty acids, though this step accounts for only about 10-30% of total lipid digestion.[83] The majority of hydrolysis takes place in the small intestine, where pancreatic lipase, in conjunction with colipase, efficiently cleaves triglycerides at the sn-1 and sn-3 positions, yielding free fatty acids and 2-monoglycerides.[83] Colipase anchors the lipase to the lipid-water interface, counteracting the inhibitory effects of bile salts.[83] Following hydrolysis, the lipolytic products—free fatty acids and 2-monoglycerides—are rendered soluble by bile salts secreted from the liver and stored in the gallbladder. These amphipathic bile salts form mixed micelles (approximately 4-8 nm in diameter) that incorporate the hydrophobic fatty acids and monoglycerides, along with cholesterol and other lipids, facilitating their transport to the brush border of enterocytes in the jejunum.[83][84] Absorption into enterocytes occurs primarily via passive diffusion across the unstirred water layer, with contributions from transmembrane proteins such as CD36/FAT and fatty acid transport protein 4 (FATP4).[83] Within the enterocytes, absorbed fatty acids and 2-monoglycerides are rapidly re-esterified into triglycerides via the monoacylglycerol pathway, involving enzymes like monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MGAT) and diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT).[83] These triglycerides are then packaged with apolipoprotein B-48 (apoB-48), phospholipids, and cholesterol esters into chylomicrons in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, a process dependent on microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP).[83] Chylomicrons are exocytosed from enterocytes into the lacteals of the villi and enter the lymphatic system (thoracic duct), bypassing the portal vein to deliver lipids directly into the systemic bloodstream.[83][84] In contrast, short- and medium-chain fatty acids (typically 2-12 carbons) do not require micelle formation; they are absorbed directly by enterocytes and transported via the portal vein to the liver bound to albumin, due to their higher water solubility.[83] The process is regulated by enteroendocrine hormones, notably cholecystokinin (CCK), which is released from I-cells in the duodenum and jejunum in response to fatty acids and amino acids in the chyme. CCK stimulates gallbladder contraction for bile release and pancreatic secretion of lipase and colipase, optimizing lipid emulsification and hydrolysis.[85][86]Catabolic Pathways

Fatty acids are activated in the cytosol by acyl-CoA synthetases, which catalyze the reaction between the fatty acid, coenzyme A (CoA), and ATP to form acyl-CoA, AMP, and pyrophosphate; this activation step consumes the equivalent of two ATP molecules due to the subsequent hydrolysis of pyrophosphate to two inorganic phosphates.[87] Following activation, long-chain acyl-CoA esters are transported into the mitochondrial matrix via the carnitine shuttle system, a prerequisite detailed in fatty acid absorption and transport processes.[87] The principal catabolic pathway for fatty acids is β-oxidation, a repetitive four-step cycle that sequentially removes two-carbon units as acetyl-CoA, primarily occurring in the mitochondrial matrix for long-chain fatty acids (LCFA, 12–20 carbons) and in peroxisomes for very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFA, >20 carbons).[87] The cycle begins with dehydrogenation of acyl-CoA to form trans-Δ²-enoyl-CoA, catalyzed by acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (e.g., very long-chain, medium-chain, or short-chain variants) and producing FADH₂.[87] This is followed by hydration to L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA via enoyl-CoA hydratase (crotonase), oxidation to 3-ketoacyl-CoA by 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase using NAD⁺ to yield NADH and H⁺, and finally thiolysis by thiolase (e.g., mitochondrial trifunctional protein or β-ketothiolase) to produce acetyl-CoA and a shortened acyl-CoA that re-enters the cycle.[87] Each turn of the β-oxidation cycle generates one FADH₂ and one NADH, which yield a net of 4 ATP upon oxidation in the electron transport chain (assuming P/O ratios of 1.5 for FADH₂ and 2.5 for NADH).[87] For the saturated even-chain fatty acid palmitate (C16:0), complete β-oxidation requires seven cycles, yielding eight acetyl-CoA units that can enter the citric acid cycle for further energy production.[87] The overall reaction is: This process, minus the 2 ATP equivalents for activation, provides a net energy yield of approximately 106 ATP molecules when accounting for the oxidation of reduced coenzymes and acetyl-CoA through oxidative phosphorylation.[87] Unsaturated fatty acids require additional enzymatic steps during β-oxidation to handle double bonds: for monounsaturated fatty acids like oleate, Δ³-cis-enoyl-CoA is isomerized to trans-Δ²-enoyl-CoA by 2,4-dienoyl-CoA Δ³,Δ²-isomerase (DCI), allowing continuation of the cycle; polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleate, additionally involve reduction by 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase (DECR1) to remove conjugated double bonds.[87] Odd-chain fatty acids, less common in diets but present in some microbial lipids, undergo β-oxidation to yield propionyl-CoA as the final three-carbon unit, which is carboxylated to D-methylmalonyl-CoA by propionyl-CoA carboxylase (using biotin and ATP), racemized to L-methylmalonyl-CoA, and rearranged to succinyl-CoA by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (vitamin B12-dependent), entering the citric acid cycle as a gluconeogenic precursor.[87] When β-oxidation produces excess acetyl-CoA beyond the liver's citric acid cycle capacity, particularly during fasting or prolonged exercise, it is diverted to ketogenesis in hepatic mitochondria to generate ketone bodies (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate) for export to extrahepatic tissues as an alternative fuel source.[88] This pathway begins with the reversible condensation of two acetyl-CoA to acetoacetyl-CoA by acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase, followed by addition of another acetyl-CoA to form 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) via HMG-CoA synthase (the rate-limiting enzyme, induced by fasting), and cleavage by HMG-CoA lyase to acetoacetate, which is partially reduced to β-hydroxybutyrate by β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase.[88]Anabolic Pathways and Essential Fatty Acids

In anabolic pathways, fatty acids serve as building blocks for the synthesis of more complex lipids, including longer-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) through processes like elongation and desaturation. These pathways occur primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum and peroxisomes of mammalian cells, where enzymes add carbon atoms via elongation or introduce double bonds via desaturation. Following the initial biosynthesis of saturated fatty acids like palmitate, further modification of essential PUFAs—linoleic acid (LA, 18:2 ω-6) and α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3 ω-3)—relies on alternating cycles of desaturation and elongation to produce bioactive longer-chain PUFAs such as arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 ω-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 ω-3). The key rate-limiting enzymes include Δ6-desaturase (FADS2), which initiates the conversion by introducing a double bond at the Δ6 position, and Δ5-desaturase (FADS1), which acts later in the pathway; elongases such as ELOVL2 and ELOVL5 add two-carbon units between these steps.[89][90][91] Humans and other mammals lack the Δ12- and Δ15-desaturases needed to insert double bonds at the ω-6 and ω-3 positions, respectively, making LA and ALA essential fatty acids that must be obtained from the diet. These precursors are then metabolized into longer-chain PUFAs critical for eicosanoid production, membrane fluidity, and neural development. Deficiency in essential fatty acids arises from inadequate dietary intake, leading to symptoms such as scaly dermatitis, poor wound healing, and growth retardation in children, as observed in cases of prolonged parenteral nutrition without lipid supplementation.[3][92][93] The conversion pathways from LA and ALA highlight the competitive nature of these anabolic processes, as both ω-6 and ω-3 substrates vie for the same desaturase and elongase enzymes, often favoring ω-6 metabolism due to higher dietary availability. The ω-6 pathway proceeds as follows:- LA (18:2 ω-6) → γ-linolenic acid (GLA, 18:3 ω-6) via Δ6-desaturase

- GLA → dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA, 20:3 ω-6) via elongation

- DGLA → AA (20:4 ω-6) via Δ5-desaturase

- ALA (18:3 ω-3) → stearidonic acid (SDA, 18:4 ω-3) via Δ6-desaturase

- SDA → eicosatetraenoic acid (ETA, 20:4 ω-3) via elongation

- ETA → eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 ω-3) via Δ5-desaturase

- EPA → docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5 ω-3) via elongation

- DPA → DHA (22:6 ω-3) via peroxisomal Δ4-desaturase or further elongation/desaturation