Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

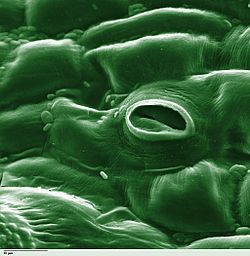

Stoma

View on Wikipedia

In botany, a stoma (pl.: stomata, from Greek στόμα, "mouth"), also called a stomate (pl.: stomates), is a pore found in the epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exchange between the internal air spaces of the leaf and the atmosphere. The pore is bordered by a pair of specialized parenchyma cells known as guard cells that regulate the size of the stomatal opening.

The term is usually used collectively to refer to the entire stomatal complex, consisting of the paired guard cells and the pore itself, which is referred to as the stomatal aperture.[1] Air, containing oxygen, which is used in respiration, and carbon dioxide, which is used in photosynthesis, passes through stomata by gaseous diffusion. Water vapour diffuses through the stomata into the atmosphere as part of a process called transpiration.

Stomata are present in the sporophyte generation of the vast majority of land plants, with the exception of liverworts, as well as some mosses and hornworts. In vascular plants the number, size and distribution of stomata varies widely. Dicotyledons usually have more stomata on the lower surface of the leaves than the upper surface. Monocotyledons such as onion, oat and maize may have about the same number of stomata on both leaf surfaces.[2]: 5 In plants with floating leaves, stomata may be found only on the upper epidermis and submerged leaves may lack stomata entirely. Most tree species have stomata only on the lower leaf surface.[3] Leaves with stomata on both the upper and lower leaf surfaces are called amphistomatous leaves; leaves with stomata only on the lower surface are hypostomatous, and leaves with stomata only on the upper surface are epistomatous or hyperstomatous.[3] Size varies across species, with end-to-end lengths ranging from 10 to 80 μm and width ranging from a few to 50 μm.[4]

Function

[edit]

CO2 gain and water loss

[edit]Carbon dioxide, a key reactant in photosynthesis, is present in the atmosphere at a concentration of about 400 ppm. Most plants require the stomata to be open during daytime. The air spaces in the leaf are saturated with water vapour, which exits the leaf through the stomata in a process known as transpiration. Therefore, plants cannot gain carbon dioxide without simultaneously losing water vapour.[5]

Alternative approaches

[edit]Ordinarily, carbon dioxide is fixed to ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) by the enzyme RuBisCO in mesophyll cells exposed directly to the air spaces inside the leaf. This exacerbates the transpiration problem for two reasons: first, RuBisCo has a relatively low affinity for carbon dioxide, and second, it fixes oxygen to RuBP, wasting energy and carbon in a process called photorespiration. For both of these reasons, RuBisCo needs high carbon dioxide concentrations, which means wide stomatal apertures and, as a consequence, high water loss.

Narrower stomatal apertures can be used in conjunction with an intermediary molecule with a high carbon dioxide affinity, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPcase). Retrieving the products of carbon fixation from PEPCase is an energy-intensive process, however. As a result, the PEPCase alternative is preferable only where water is limiting but light is plentiful, or where high temperatures increase the solubility of oxygen relative to that of carbon dioxide, magnifying RuBisCo's oxygenation problem.

C.A.M. plants

[edit]

A group of mostly desert plants called "C.A.M." plants (crassulacean acid metabolism, after the family Crassulaceae, which includes the species in which the CAM process was first discovered) open their stomata at night (when water evaporates more slowly from leaves for a given degree of stomatal opening), use PEPcase to fix carbon dioxide and store the products in large vacuoles. The following day, they close their stomata and release the carbon dioxide fixed the previous night into the presence of RuBisCO. This saturates RuBisCO with carbon dioxide, allowing minimal photorespiration. This approach, however, is severely limited by the capacity to store fixed carbon in the vacuoles, so it is preferable only when water is severely limited.

Opening and closing

[edit]

However, most plants do not have CAM and must therefore open and close their stomata during the daytime, in response to changing conditions, such as light intensity, humidity, and carbon dioxide concentration. When conditions are conducive to stomatal opening (e.g., high light intensity and high humidity), a proton pump drives protons (H+) from the guard cells. This means that the cells' electrical potential becomes increasingly negative. The negative potential opens potassium voltage-gated channels and so an uptake of potassium ions (K+) occurs. To maintain this internal negative voltage so that entry of potassium ions does not stop, negative ions balance the influx of potassium. In some cases, chloride ions enter, while in other plants the organic ion malate is produced in guard cells. This increase in solute concentration lowers the water potential inside the cell, which results in the diffusion of water into the cell through osmosis. This increases the cell's volume and turgor pressure. Then, because of rings of cellulose microfibrils that prevent the width of the guard cells from swelling, and thus only allow the extra turgor pressure to elongate the guard cells, whose ends are held firmly in place by surrounding epidermal cells, the two guard cells lengthen by bowing apart from one another, creating an open pore through which gas can diffuse.[6]

When the roots begin to sense a water shortage in the soil, abscisic acid (ABA) is released.[7] ABA binds to receptor proteins in the guard cells' plasma membrane and cytosol, which first raises the pH of the cytosol of the cells and cause the concentration of free Ca2+ to increase in the cytosol due to influx from outside the cell and release of Ca2+ from internal stores such as the endoplasmic reticulum and vacuoles.[8] This causes the chloride (Cl−) and organic ions to exit the cells. Second, this stops the uptake of any further K+ into the cells and, subsequently, the loss of K+. The loss of these solutes causes an increase in water potential, which results in the diffusion of water back out of the cell by osmosis. This makes the cell plasmolysed, which results in the closing of the stomatal pores.

Guard cells have more chloroplasts than the other epidermal cells from which guard cells are derived. Their function is controversial.[9][10]

Inferring stomatal behavior from gas exchange

[edit]The degree of stomatal resistance can be determined by measuring leaf gas exchange of a leaf. The transpiration rate is dependent on the diffusion resistance provided by the stomatal pores and also on the humidity gradient between the leaf's internal air spaces and the outside air. Stomatal resistance (or its inverse, stomatal conductance) can therefore be calculated from the transpiration rate and humidity gradient. This allows scientists to investigate how stomata respond to changes in environmental conditions, such as light intensity and concentrations of gases such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and ozone.[11] Evaporation (E) can be calculated as[12]

where ei and ea are the partial pressures of water in the leaf and in the ambient air respectively, P is atmospheric pressure, and r is stomatal resistance. The inverse of r is conductance to water vapor (g), so the equation can be rearranged to[12]

and solved for g:[12]

Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation (A) can be calculated from

where Ca and Ci are the atmospheric and sub-stomatal partial pressures of CO2 respectively[clarification needed]. The rate of evaporation from a leaf can be determined using a photosynthesis system. These scientific instruments measure the amount of water vapour leaving the leaf and the vapor pressure of the ambient air. Photosynthetic systems may calculate water use efficiency (A/E), g, intrinsic water use efficiency (A/g), and Ci. These scientific instruments are commonly used by plant physiologists to measure CO2 uptake and thus measure photosynthetic rate.[13][14]

Evolution

[edit]

There is little evidence of the evolution of stomata in the fossil record, but they had appeared in land plants by the middle of the Silurian period.[15] They may have evolved by the modification of conceptacles from plants' alga-like ancestors.[16] However, the evolution of stomata must have happened at the same time as the waxy cuticle was evolving – these two traits together constituted a major advantage for early terrestrial plants.[citation needed]

Development

[edit]There are three major epidermal cell types which all ultimately derive from the outermost (L1) tissue layer of the shoot apical meristem, called protodermal cells: trichomes, pavement cells and guard cells, all of which are arranged in a non-random fashion.

An asymmetrical cell division occurs in protodermal cells resulting in one large cell that is fated to become a pavement cell and a smaller cell called a meristemoid that will eventually differentiate into the guard cells that surround a stoma. This meristemoid then divides asymmetrically one to three times before differentiating into a guard mother cell. The guard mother cell then makes one symmetrical division, which forms a pair of guard cells.[17] Cell division is inhibited in some cells so there is always at least one cell between stomata.[18]

Stomatal patterning is controlled by the interaction of many signal transduction components such as EPF (Epidermal Patterning Factor), ERL (ERecta Like) and YODA (a putative MAP kinase kinase kinase).[18] Mutations in any one of the genes which encode these factors may alter the development of stomata in the epidermis.[18] For example, a mutation in one gene causes more stomata that are clustered together, hence is called Too Many Mouths (TMM).[17] Whereas, disruption of the SPCH (SPeecCHless) gene prevents stomatal development all together.[18] Inhibition of stomatal production can occur by the activation of EPF1, which activates TMM/ERL, which together activate YODA. YODA inhibits SPCH, causing SPCH activity to decrease, preventing asymmetrical cell division that initiates stomata formation.[18][19] Stomatal development is also coordinated by the cellular peptide signal called stomagen, which signals the activation of the SPCH, resulting in increased number of stomata.[20]

Environmental and hormonal factors can affect stomatal development. Light increases stomatal development in plants; while, plants grown in the dark have a lower amount of stomata. Auxin represses stomatal development by affecting their development at the receptor level like the ERL and TMM receptors. However, a low concentration of auxin allows for equal division of a guard mother cell and increases the chance of producing guard cells.[21]

Most angiosperm trees have stomata only on their lower leaf surface. Poplars and willows have them on both surfaces. When leaves develop stomata on both leaf surfaces, the stomata on the lower surface tend to be larger and more numerous, but there can be a great degree of variation in size and frequency about species and genotypes. White ash and white birch leaves had fewer stomata but larger in size. On the other hand sugar maple and silver maple had small stomata that were more numerous.[22]

Types

[edit]Different classifications of stoma types exist. One that is widely used is based on the types that Julien Joseph Vesque introduced in 1889, was further developed by Metcalfe and Chalk,[23] and later complemented by other authors. It is based on the size, shape and arrangement of the subsidiary cells that surround the two guard cells.[24] They distinguish for dicots:

- actinocytic (meaning star-celled) stomata have guard cells that are surrounded by at least five radiating cells forming a star-like circle. This is a rare type that can for instance be found in the family Ebenaceae.

- anisocytic (meaning unequal celled) stomata have guard cells between two larger subsidiary cells and one distinctly smaller one. This type of stomata can be found in more than thirty dicot families, including Brassicaceae, Solanaceae, and Crassulaceae. It is sometimes called cruciferous type.

- anomocytic (meaning irregular celled) stomata have guard cells that are surrounded by cells that have the same size, shape and arrangement as the rest of the epidermis cells. This type of stomata can be found in more than hundred dicot families such as Apocynaceae, Boraginaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Cucurbitaceae. It is sometimes called ranunculaceous type.

- diacytic (meaning cross-celled) stomata have guard cells surrounded by two subsidiary cells, that each encircle one end of the opening and contact each other opposite to the middle of the opening. This type of stomata can be found in more than ten dicot families such as Caryophyllaceae and Acanthaceae. It is sometimes called caryophyllaceous type.

- hemiparacytic stomata are bordered by just one subsidiary cell that differs from the surrounding epidermis cells, its length parallel to the stoma opening. This type occurs for instance in the Molluginaceae and Aizoaceae.

- paracytic (meaning parallel celled) stomata have one or more subsidiary cells parallel to the opening between the guard cells. These subsidiary cells may reach beyond the guard cells or not. This type of stomata can be found in more than hundred dicot families such as Rubiaceae, Convolvulaceae and Fabaceae. It is sometimes called rubiaceous type.

In monocots, several different types of stomata occur such as:

- gramineous or graminoid (meaning grass-like) stomata have two guard cells surrounded by two lens-shaped subsidiary cells. The guard cells are narrower in the middle and bulbous on each end. This middle section is strongly thickened. The axis of the subsidiary cells are parallel stoma opening. This type can be found in monocot families including Poaceae and Cyperaceae.[25]

- hexacytic (meaning six-celled) stomata have six subsidiary cells around both guard cells, one at either end of the opening of the stoma, one adjoining each guard cell, and one between that last subsidiary cell and the standard epidermis cells. This type can be found in some monocot families.

- tetracytic (meaning four-celled) stomata have four subsidiary cells, one on either end of the opening, and one next to each guard cell. This type occurs in many monocot families, but also can be found in some dicots, such as Tilia and several Asclepiadaceae.

In ferns, four different types are distinguished:

- hypocytic stomata have two guard cells in one layer with only ordinary epidermis cells, but with two subsidiary cells on the outer surface of the epidermis, arranged parallel to the guard cells, with a pore between them, overlying the stoma opening.

- pericytic stomata have two guard cells that are entirely encircled by one continuous subsidiary cell (like a donut).

- desmocytic stomata have two guard cells that are entirely encircled by one subsidiary cell that has not merged its ends (like a sausage).

- polocytic stomata have two guard cells that are largely encircled by one subsidiary cell, but also contact ordinary epidermis cells (like a U or horseshoe).

A catalogue of leaf epidermis prints showing stomata from a wide range of species can be found in Wikimedia commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Leaf_epidermis_and_stomata_prints

Stomatal crypts

[edit]Stomatal crypts are sunken areas of the leaf epidermis which form a chamber-like structure that contains one or more stomata and sometimes trichomes or accumulations of wax. Stomatal crypts can be an adaption to drought and dry climate conditions when the stomatal crypts are very pronounced. However, dry climates are not the only places where they can be found. The following plants are examples of species with stomatal crypts or antechambers: Nerium oleander, conifers, Hakea[26] and Drimys winteri which is a species of plant found in the cloud forest.[27]

Stomata as pathogenic pathways

[edit]Stomata are holes in the leaf by which pathogens can enter unchallenged. However, stomata can sense the presence of some, if not all, pathogens.[28] However, pathogenic bacteria applied to Arabidopsis plant leaves can release the chemical coronatine, which induce the stomata to reopen. [29]

Stomata and climate change

[edit]Response of stomata to environmental factors

[edit]Photosynthesis, plant water transport (xylem) and gas exchange are regulated by stomatal function which is important in the functioning of plants.[30]

Stomata are responsive to light with blue light being almost 10 times as effective as red light in causing stomatal response. Research suggests this is because the light response of stomata to blue light is independent of other leaf components like chlorophyll. Guard cell protoplasts swell under blue light provided there is sufficient availability of potassium.[31] Multiple studies have found support that increasing potassium concentrations may increase stomatal opening in the mornings, before the photosynthesis process starts, but that later in the day sucrose plays a larger role in regulating stomatal opening.[32] Zeaxanthin in guard cells acts as a blue light photoreceptor which mediates the stomatal opening.[33] The effect of blue light on guard cells is reversed by green light, which isomerizes zeaxanthin.[33]

Stomatal density and aperture (length of stomata) varies under a number of environmental factors such as atmospheric CO2 concentration, light intensity, air temperature and photoperiod (daytime duration). [34][35]

Decreasing stomatal density is one way plants have responded to the increase in concentration of atmospheric CO2 ([CO2]atm).[36] Although changes in [CO2]atm response is the least understood mechanistically, this stomatal response has begun to plateau where it is soon expected to impact transpiration and photosynthesis processes in plants.[30][37]

Drought inhibits stomatal opening, but research on soybeans suggests moderate drought does not have a significant effect on stomatal closure of its leaves. There are different mechanisms of stomatal closure. Low humidity stresses guard cells causing turgor loss, termed hydropassive closure. Hydroactive closure is contrasted as the whole leaf affected by drought stress, believed to be most likely triggered by abscisic acid.[38]

Future adaptations during climate change

[edit]It is expected that [CO2]atm will reach 500–1000 ppm by 2100.[30] 96% of the past 400,000 years experienced below 280 ppm CO2. From this figure, it is highly probable that genotypes of today's plants have diverged from their pre-industrial relatives.[30]

The gene HIC (high carbon dioxide) encodes a negative regulator for the development of stomata in plants.[39] Research into the HIC gene using Arabidopsis thaliana found no increase of stomatal development in the dominant allele, but in the 'wild type' recessive allele showed a large increase, both in response to rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere.[39] These studies imply the plants response to changing CO2 levels is largely controlled by genetics.

Agricultural implications

[edit]The CO2 fertiliser effect has been greatly overestimated during Free-Air Carbon dioxide Enrichment (FACE) experiments where results show increased CO2 levels in the atmosphere enhances photosynthesis, reduce transpiration, and increase water use efficiency (WUE).[36] Increased biomass is one of the effects with simulations from experiments predicting a 5–20% increase in crop yields at 550 ppm of CO2.[40] Rates of leaf photosynthesis were shown to increase by 30–50% in C3 plants, and 10–25% in C4 under doubled CO2 levels.[40] The existence of a feedback mechanism results a phenotypic plasticity in response to [CO2]atm that may have been an adaptive trait in the evolution of plant respiration and function.[30][35]

Predicting how stomata perform during adaptation is useful for understanding the productivity of plant systems for both natural and agricultural systems.[34] Plant breeders and farmers are beginning to work together using evolutionary and participatory plant breeding to find the best suited species such as heat and drought resistant crop varieties that could naturally evolve to the change in the face of food security challenges.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ Esau, K. (1977). Anatomy of Seed Plants. Wiley and Sons. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-471-24520-9.

- ^ Weyers, J. D. B.; Meidner, H. (1990). Methods in stomatal research. Longman Group UK Ltd. ISBN 978-0-582-03483-9.

- ^ a b Willmer, Colin; Fricker, Mark (1996). Stomata. Springer. p. 16. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0579-8. ISBN 978-94-010-4256-7. S2CID 224833888.

- ^ Fricker, M.; Willmer, C. (2012). Stomata. Springer Netherlands. p. 18. ISBN 978-94-011-0579-8. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Debbie Swarthout and C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Stomata. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

- ^ N. S. CHRISTODOULAKIS; J. MENTI; B. GALATIS (January 2002). "Structure and Development of Stomata on the Primary Root of Ceratonia siliqua L." Annals of Botany. 89 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1093/aob/mcf002. PMC 4233769. PMID 12096815.

- ^ C. L. Trejo; W. J. Davies; LdMP. Ruiz (1993). "Sensitivity of Stomata to Abscisic Acid (An Effect of the Mesophyll)". Plant Physiology. 102 (2): 497–502. doi:10.1104/pp.102.2.497. PMC 158804. PMID 12231838.

- ^ Petra Dietrich; Dale Sanders; Rainer Hedrich (October 2001). "The role of ion channels in light-dependent stomatal opening". Journal of Experimental Botany. 52 (363): 1959–1967. doi:10.1093/jexbot/52.363.1959. PMID 11559731.

- ^ "Guard Cell Photosynthesis". Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- ^ Eduardo Zeiger; Lawrence D. Talbott; Silvia Frechilla; Alaka Srivastava; Jianxin Zhu (March 2002). "The Guard Cell Chloroplast: A Perspective for the Twenty-First Century". New Phytologist. 153 (3 Special Issue: Stomata): 415–424. Bibcode:2002NewPh.153..415Z. doi:10.1046/j.0028-646X.2001.NPH328.doc.x. PMID 33863211.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (2007-07-26). "Carbon sinks threatened by increasing ozone". Nature. 448 (7152): 396–397. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..396H. doi:10.1038/448396b. PMID 17653153.

- ^ a b c "Calculating Important Parameters in Leaf Gas Exchange". Plant Physiology Online. Sinauer. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ^ Waichi Agata; Yoshinobu Kawamitsu; Susumu Hakoyama; Yasuo Shima (January 1986). "A system for measuring leaf gas exchange based on regulating vapour pressure difference". Photosynthesis Research. 9 (3): 345–357. Bibcode:1986PhoRe...9..345A. doi:10.1007/BF00029799. ISSN 1573-5079. PMID 24442366. S2CID 28367821.

- ^ Portable Gas Exchange Fluorescence System GFS-3000. Handbook of Operation (PDF), March 20, 2013, archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2017, retrieved October 20, 2014

- ^ D. Edwards, H. Kerp; Hass, H. (1998). "Stomata in early land plants: an anatomical and ecophysiological approach". Journal of Experimental Botany. 49 (Special Issue): 255–278. doi:10.1093/jxb/49.Special_Issue.255.

- ^ Krassilov, Valentin A. (2004). "Macroevolutionary events and the origin of higher taxa". In Wasser, Solomon P. (ed.). Evolutionary theory and processes : modern horizons: papers in honour of Eviatar Nevo. Dordrecht: Kluwer Acad. Publ. pp. 265–289. ISBN 978-1-4020-1693-6.

- ^ a b Bergmann, Dominique C.; Lukowitz, Wolfgang; Somerville, Chris R.; Lukowitz, W; Somerville, CR (4 July 2004). "Stomatal Development and Pattern Controlled by a MAPKK Kinase". Science. 304 (5676): 1494–1497. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1494B. doi:10.1126/science.1096014. PMID 15178800. S2CID 32009729.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Pillitteri, Lynn Jo; Dong, Juan (2013-06-06). "Stomatal Development in Arabidopsis". The Arabidopsis Book. 11 e0162. doi:10.1199/tab.0162. ISSN 1543-8120. PMC 3711358. PMID 23864836.

- ^ Casson, Stuart A; Hetherington, Alistair M (2010-02-01). "Environmental regulation of stomatal development". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 13 (1): 90–95. Bibcode:2010COPB...13...90C. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2009.08.005. PMID 19781980.

- ^ Sugano, Shigeo S.; Shimada, Tomoo; Imai, Yu; Okawa, Katsuya; Tamai, Atsushi; Mori, Masashi; Hara-Nishimura, Ikuko (2010-01-14). "Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis". Nature. 463 (7278): 241–244. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..241S. doi:10.1038/nature08682. hdl:2433/91250. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20010603. S2CID 4302041.

- ^ Balcerowicz, M.; Ranjan, A.; Rupprecht, L.; Fiene, G.; Hoecker, U. (2014). "Auxin represses stomatal development in dark-grown seedling via Aux/IAA proteins". Development. 141 (16): 3165–3176. doi:10.1242/dev.109181. PMID 25063454.

- ^ Pallardy, Stephen (1983). "Physiology of Woody Plants". Journal of Applied Ecology. 20 (1): 14. Bibcode:1983JApEc..20..352J. doi:10.2307/2403413. JSTOR 2403413.

- ^ Metcalfe, C.R.; Chalk, L. (1950). Anatomy of Dicotyledons. Vol. 1: Leaves, Stem, and Wood in relation to Taxonomy, with notes on economic Uses.

- ^ van Cotthem, W.R.F. (1970). "A Classification of Stomatal Types". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 63 (3): 235–246. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1970.tb02321.x.

- ^ Nunes, Tiago D. G.; Zhang, Dan; Raissig, Michael T. (February 2020). "Form, development and function of grass stomata". The Plant Journal. 101 (4): 780–799. Bibcode:2020PlJ...101..780N. doi:10.1111/tpj.14552. PMID 31571301.

- ^ Jordan, Gregory J; Weston, Peter H; Carpenter, Raymond J; Dillon, Rebecca A.; Brodribb, Timothy J. (2008). "The evolutionary relations of sunken, covered, and encrypted stomata to dry habitats in Proteaceae". American Journal of Botany. 95 (5): 521–530. Bibcode:2008AmJB...95..521J. doi:10.3732/ajb.2007333. PMID 21632378.

- ^ Roth-Nebelsick, A.; Hassiotou, F.; Veneklaas, E. J (2009). "Stomatal crypts have small effects on transpiration: A numerical model analysis". Plant Physiology. 151 (4): 2018–2027. doi:10.1104/pp.109.146969. PMC 2785996. PMID 19864375.

- ^ Maeli Melotto; William Underwood; Jessica Koczan; Kinya Nomura; Sheng Yang He (2006). "Plant Stomata in innate immunity against bacterial invasion". Cell. 126 (5): 969–980. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.054. PMID 16959575. S2CID 13612107.

- ^ Schulze-Lefert, P; Robatzek, S (2006). "Plant pathogens trick guard cells into opening the gates". Cell. 126 (5): 831–834. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.020. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-394E-B. PMID 16959560.

- ^ a b c d e Rico, C; Pittermann, J; Polley, HW; Aspinwall, MJ; Fay, PA (2013). "The effect of subambient to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on vascular function in Helianthus annuus: implications for plant response to climate change". New Phytologist. 199 (4): 956–965. Bibcode:2013NewPh.199..956R. doi:10.1111/nph.12339. PMID 23731256.

- ^ McDonald, Maurice S. (2003). Photobiology of Higher Plants. Wiley. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-470-85523-2.

- ^ Mengel, Konrad; Kirkby, Ernest A.; Kosegarten, Harald; Appel, Thomas, eds. (2001). Principles of Plant Nutrition. Springer. p. 205. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2. ISBN 978-94-010-1009-2. S2CID 9332099.

- ^ a b Kochhar, S. L.; Gujral, Sukhbir Kaur (2020). "Transpiration". Plant Physiology: Theory and Applications (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–99. doi:10.1017/9781108486392.006. ISBN 978-1-108-48639-2.

- ^ a b Buckley, TN; Mott, KA (2013). "Modelling stomatal conductance in response to environmental factors". Plant, Cell and Environment. 36 (9): 1691–1699. Bibcode:2013PCEnv..36.1691B. doi:10.1111/pce.12140. PMID 23730938.

- ^ a b Rogiers, SY; Hardie, WJ; Smith, JP (2011). "Stomatal density of grapevine leaves (Vitis Vinifera L.) responds to soil temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide". Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 17 (2): 147–152. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00124.x.

- ^ a b c Ceccarelli, S; Grando, S; Maatougui, M; Michael, M; Slash, M; Haghparast, R; Rahmanian, M; Taheri, A; Al-Yassin, A; Benbelkacem, A; Labdi, M; Mimoun, H; Nachit, M (2010). "Plant breeding and climate changes". The Journal of Agricultural Science. 148 (6): 627–637. doi:10.1017/s0021859610000651. S2CID 86237270.

- ^ Serna, L; Fenoll, C (2000). "Coping with human CO2 emissions". Nature. 408 (6813): 656–657. doi:10.1038/35047202. PMID 11130053. S2CID 39010041.

- ^ Mengel, Konrad; Kirkby, Ernest A.; Kosegarten, Harald; Appel, Thomas, eds. (2001). Principles of Plant Nutrition. Springer. p. 223. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2. ISBN 978-94-010-1009-2. S2CID 9332099.

- ^ a b Gray, J; Holroyd, G; van der Lee, F; Bahrami, A; Sijmons, P; Woodward, F; Schuch, W; Hetherington, A (2000). "The HIC signalling pathway links CO2 perception to stomatal development". Nature. 408 (6813): 713–716. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..713G. doi:10.1038/35047071. PMID 11130071. S2CID 83843467.

- ^ a b Tubiello, FN; Soussana, J-F; Howden, SM (2007). "Crop and pasture response to climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (50): 19686–19690. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419686T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701728104. PMC 2148358. PMID 18077401.

External links

[edit]Stoma

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Physiology

Microscopic Structure

The stomatal complex consists of a central pore bordered by a pair of specialized guard cells embedded in the plant epidermis.[9] These guard cells are derived from epidermal parenchyma and function to regulate the pore's aperture through changes in turgor pressure.[10] Microscopically, guard cells appear kidney-shaped in most dicotyledons and ferns, or dumbbell-shaped in grasses and other monocotyledons, with the pore forming between their ventral walls.[10] Unlike surrounding epidermal cells, guard cells contain chloroplasts, enabling photosynthetic activity and ion transport linked to stomatal movement./03:_Plant_Structure/3.04:_Leaves/3.4.02:_Internal_Leaf_Structure) Guard cell walls exhibit asymmetric thickening, with radial orientation of cellulose microfibrils in the dorsal wall and longitudinal in the ventral wall, facilitating asymmetric expansion during opening.[11] The ventral walls adjacent to the pore are notably thinner, composed primarily of cellulose and pectin matrices that allow deformation under turgor changes.[12] Subsidiary cells, often flanking the guard cells in specific patterns, provide structural support and may assist in ion flux, though their presence varies by stomatal type.[13] Under light microscopy, stomata are observable on leaf peels or cleared sections, revealing the pore dimensions typically ranging from 10-20 micrometers in length.[14] Scanning electron microscopy discloses finer details, such as wax plugs or cuticular ridges around the pore that minimize unregulated water loss.[12] These structural features ensure efficient gas diffusion while adapting to environmental stresses.[11]Gas Exchange and Photosynthesis Support

Stomata function as the principal conduits for gaseous diffusion in terrestrial plants, permitting the influx of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) required for photosynthetic carbon fixation while facilitating the efflux of oxygen (O₂) generated as a byproduct. This exchange occurs primarily through the stomatal pore, bordered by guard cells, which adjust aperture size to modulate conductance. The impermeability of the leaf cuticle to gases underscores the stomata's indispensable role, as their absence would drastically curtail diffusion rates, limiting photosynthesis to negligible levels.[15][4][16] The diffusive flux of CO₂ and O₂ adheres to Fick's first law, expressed as the net rate J = D × (ΔC / Δx) × A, where D represents the diffusion coefficient, ΔC the concentration gradient across the pore, Δx the diffusion path length (typically short within the substomatal cavity), and A the effective pore area determined by stomatal aperture. Stomatal conductance (g_s), measured in mol m⁻² s⁻¹, integrates these factors and directly influences intercellular CO₂ concentration (C_i), which in turn drives the photosynthetic rate A via the relation A ≈ g_{sc} × (C_i - Γ), where g_{sc} is CO₂ stomatal conductance (g_s scaled by the diffusivity ratio of 1.6 relative to water vapor) and Γ the CO₂ compensation point. Elevated g_s enhances C_i, alleviating diffusive limitations to Rubisco carboxylation, particularly under high irradiance when photosynthetic demand peaks, but concurrently amplifies O₂ release and water vapor loss.[17][18][19] In supporting photosynthesis, stomata exhibit dynamic responsiveness to environmental cues, opening during daylight to prioritize CO₂ uptake when mesophyll demand is maximal, thereby optimizing carbon assimilation relative to transpirational costs. Empirical measurements indicate that stomatal limitation can account for 20-50% of total photosynthetic constraints in C3 plants under ambient conditions, diminishing under elevated CO₂ where partial closure sustains A through improved carboxylation efficiency despite reduced g_s. This interplay ensures that gas exchange supports not only immediate photosynthetic throughput but also long-term plant productivity by balancing resource acquisition amid varying atmospheric compositions.[19][20][21]Regulation of Opening and Closing

The opening and closing of stomata are primarily regulated by changes in turgor pressure within the pair of guard cells that surround each pore. When guard cells increase in turgor, they swell asymmetrically due to their thickened inner walls, causing the pore to open and facilitate gas exchange. Conversely, loss of turgor leads to pore closure, conserving water during stress conditions. This turgor-driven mechanism integrates environmental signals to balance CO2 uptake for photosynthesis against transpirational water loss.[22][23] Stomatal opening is predominantly triggered by light, with blue light acting as the primary cue through phototropin receptors (PHOT1 and PHOT2). Blue light induces autophosphorylation of phototropins, activating plasma membrane H+-ATPases that pump protons out of guard cells, hyperpolarizing the membrane and enabling K+ influx via inward-rectifying channels. This ion accumulation drives osmotic water uptake, increasing vacuolar volume and turgor pressure, which expands the guard cells and widens the stomatal aperture. Red light synergistically enhances opening by promoting photosynthesis, which depletes intercellular CO2 and reinforces the signal, though blue light suffices for initial activation even in low CO2 environments.[24][25][26] Stomatal closure is mediated by abscisic acid (ABA), a hormone synthesized in response to drought or high vapor pressure deficit. Elevated ABA binds to receptors like PYR/PYL/RCAR, inhibiting PP2C phosphatases and activating SnRK2 kinases, which phosphorylate ion channels and pumps. This triggers efflux of K+ and anions (e.g., Cl-, malate) through outward-rectifying channels, depolarizing the membrane and reducing osmotic potential, leading to water efflux and turgor collapse. ABA signaling also elevates cytosolic Ca2+ levels, amplifying closure via downstream effectors. Darkness and elevated CO2 promote closure independently or synergistically with ABA by similar ion flux mechanisms.[27][28][25] Additional regulators fine-tune stomatal responses; for instance, low humidity accelerates ABA-induced closure to prevent excessive transpiration, while temperature modulates sensitivity through effects on membrane fluidity and enzyme kinetics. Cytoskeletal rearrangements in guard cells, involving actin and microtubules, support cell shape changes during these processes. These mechanisms ensure adaptive regulation, with guard cells responding within minutes to hours to dynamic conditions.[29][30]Trade-offs in Water Use Efficiency

Stomata enable carbon dioxide uptake for photosynthesis while driving transpiration, creating an inherent trade-off between carbon assimilation and water conservation. The net photosynthetic rate increases with stomatal conductance , approximated by , where and are ambient and intercellular CO₂ partial pressures, 1.6 reflects the diffusivity ratio of CO₂ to water vapor, and is a resistance term.[31] Concurrently, transpiration rate scales directly with , as , with and as leaf internal and ambient vapor pressures.[31] This coupling means that elevating to boost proportionally heightens , limiting whole-plant water use efficiency (WUE = ) under soil moisture constraints.[31]  Intrinsic WUE (iWUE = ) further elucidates this tension, equating to , which favors conservative stomatal behavior that maintains low to minimize per unit carbon gained, yet biochemical carboxylation capacity caps gains from further reduction.[31] Across 64 tree species, higher maximum under wet conditions—enabling peak —correlates with elevated xylem embolism vulnerability, imposing a safety-efficiency trade-off where drought-prone environments select for lower to prioritize hydraulic safety over growth.[32] Under water deficit, stomatal closure curbs by up to 90% in responsive species but slashes by 50-70%, risking carbon starvation if prolonged.[33] Photosynthetic pathway variations modulate this trade-off. C4 plants, via CO₂-concentrating mechanisms, sustain higher at 20-50% lower than C3 counterparts, yielding iWUE advantages observable in field trials.[34] CAM species temporally decouple processes by nocturnal stomatal opening—when vapor pressure deficit is 2-5 times lower—storing CO₂ as malic acid for daytime decarboxylation, attaining WUE 3-10 times superior to C3 plants in arid settings.[34] Genetic interventions, such as EPF overexpression reducing stomatal density by 30-50%, elevate iWUE 20-40% in cereals like wheat without yield penalties under moderate drought, though densities below 60% of wild-type impair and biomass by limiting CO₂ diffusion.[35] [36] Elevated atmospheric CO₂ since 1850 has universally boosted iWUE by 23-30% via diffusion-limited stomatal closure, allowing equivalent at reduced and , as evidenced by stable carbon isotope ratios (δ¹³C) in tree rings across biomes; however, concurrent aridity intensification increasingly constrains this benefit by enforcing tighter stomatal regulation.[37] These dynamics underscore stomatal as a nexus of environmental adaptation, where optimizing the assimilation-transpiration ratio demands balancing instantaneous fluxes against long-term survival risks.[38]Developmental Processes

Genetic and Molecular Controls

Stomatal development in angiosperms, particularly in the model species Arabidopsis thaliana, is governed by a sequential genetic program that specifies cell fate transitions within the epidermal protoderm. Protodermal cells initially acquire a meristemoid mother cell identity through asymmetric divisions promoted by the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH), which activates genes for cell proliferation and stomatal lineage initiation while suppressing pavement cell fate.[39] SPCH expression is transiently induced in competent protodermal cells, ensuring stochastic entry into the stomatal lineage and preventing overproduction of stomata.[40] Subsequent stages involve additional bHLH factors: MUTE terminates the proliferative meristemoid phase and induces guard mother cell (GMC) formation by upregulating genes for cell cycle exit and GMC specification, while FAMA drives the final symmetric division of the GMC into paired guard cells and promotes their maturation through expression of genes encoding cell wall components and ion channels.[41] These three factors—collectively termed stomatal master regulators (SMFs)—function in a relay, with SPCH, MUTE, and FAMA each peaking at distinct lineage stages to enforce irreversible fate decisions; mutations in these genes lead to phenotypes ranging from stomataless epidermis (spch mutants) to arrested precursors (mute) or immature guard cells (fama).[42] ICE1 and SCRM2, related bHLH proteins, heterodimerize with SMFs to enhance their DNA-binding activity and integrate environmental signals, such as light and CO2 levels, into developmental progression.[43] Molecular spacing mechanisms prevent stomatal clustering via secreted signaling peptides from the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) family, particularly EPF1 and EPF2, which are expressed in meristemoids and GMCs to inhibit adjacent cells from entering the lineage.[44] These peptides bind receptor-like kinases of the ERECTA (ER) family and are internalized via the receptor TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM), a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein, forming a feedback loop that reinforces one-cell spacing and amplifies inhibitory signals over short distances.[40] Polarity establishment during asymmetric divisions is controlled by the polarly localized protein BREAKING OF ASYMMETRY IN THE STOMATAL LINEAGE (BASL), which recruits ROP GTPases and PIN auxin transporters to bias division planes and daughter cell fates.[39] Auxin and cytokinin gradients modulate these core pathways; for instance, auxin maxima promote SPCH expression via AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARFs), while cytokinin signaling through ARR12 suppresses excessive lineage initiation.[45] Conservation of this genetic toolkit across vascular plants underscores its evolutionary significance, though diversification occurs in non-model species, such as reduced SPCH dependency in gramineae where parallel regulators compensate.[46] Recent studies highlight post-transcriptional controls, including microRNAs and chromatin modifiers, that fine-tune SMF expression for adaptive stomatal density.[47]Formation in Angiosperms and Other Groups

In angiosperms, stomatal formation initiates in the protoderm with competent epidermal cells differentiating into meristemoid mother cells (MMCs), which undergo asymmetric divisions to produce meristemoid stem cells capable of 1–3 amplifying divisions.[46] These meristemoids, regulated by basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors such as SPEECHLESS (SPCH) for initiation, MUTE for transition to guard mother cell (GMC) fate, and FAMA for terminal guard cell differentiation, eventually form a GMC that divides symmetrically into the two guard cells.[46] Spacing divisions from stomatal lineage ground cells (SLGCs) prevent adjacent stomata formation, mediated by inhibitory signaling from EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) peptides, TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM), and ERECTA-family receptor kinases, alongside mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades involving YODA and MPK3/6.[46] This paradigm, best characterized in Arabidopsis thaliana, enables high stomatal density and patterned distribution, with subsidiary cells in some lineages (e.g., grasses) arising from oriented divisions around the GMC.[48] Within angiosperms, developmental patterns vary; basal lineages like Nymphaea colorata retain orthologs of key Arabidopsis regulators but exhibit reduced or duplicated gene functions correlating with simpler stomatal complexes, while grasses employ an alternatively wired bHLH network for linear file formation from subsidiary cell precursors.[49][48] These processes occur post-meristem emergence, influenced by auxin gradients and polarity proteins like BASL for asymmetric division orientation.[46] In gymnosperms, such as conifers (Pinus spp.), stomatal ontogeny typically involves symmetric division of a meristemoid to simultaneously produce the GMC and subsidiary cells, lacking the multiple amplifying asymmetric divisions characteristic of angiosperms and often incorporating contributions from adjacent protodermal cells.[46] Subsidiary cells feature thickened cuticles and lignified walls, supporting hydroactive guard cell movement without the dedicated inhibitory feedback loops for spacing seen in flowering plants.[46] Ferns (pteridophytes) display an intermediate ontogeny, with stomatal precursors undergoing 1–2 asymmetric divisions before GMC formation, followed by subsidiary cell development from surrounding epidermal cells, enabling moderate density control but without the full sequential bHLH cascade of angiosperms.[46] In bryophytes like mosses (Physcomitrella patens), formation is simpler, involving a single asymmetric division of a precursor to yield the GMC, with expression of bHLH homologs (e.g., MUTE- and FAMA-like) but absence of SPCH function and variable cytokinesis, reflecting ancestral traits retained in sporophytes.[46] These differences underscore evolutionary innovations in angiosperms, such as amplified divisions and refined genetic inhibition, correlating with adaptations to declining atmospheric CO₂ levels around 400 million years ago.[13]Environmental Influences on Development

Stomatal development in plants displays significant phenotypic plasticity, allowing adjustments in density, index, and patterning in response to abiotic environmental cues sensed locally during leaf primordia formation or systemically via signals from mature tissues.[50][51] This plasticity operates primarily through modulation of meristemoid mother cell differentiation and spacing, influenced by factors such as light, atmospheric CO₂ concentration, temperature, and water availability, enabling plants to optimize gas exchange and water conservation under varying conditions.[52] Empirical studies demonstrate that these responses are species-specific and often involve hormonal signaling, including abscisic acid and cytokinins, integrated with genetic controls like the TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) pathway.[53] Light intensity positively correlates with stomatal density and index, with higher irradiance promoting increased formation of stomatal lineage cells during early leaf development.[54] For instance, in species like Quercus kelloggii, elevated light levels significantly raise the stomatal index without altering epidermal cell density, reflecting direct sensing by developing primordia or indirect cues from shaded versus sun-exposed leaves.[55] Systemic signaling from mature leaves exposed to high light can further enhance stomatal development in expanding leaves, as observed in experiments where light manipulation on older foliage altered stomatal traits distally.[50] This adaptation supports greater photosynthetic capacity in high-light environments, though excessive intensity may impose trade-offs via photoinhibition.[56] Elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations suppress stomatal development, leading to reduced density and index as a conserved response across angiosperms.[57] Fossil and experimental data indicate a approximately 34% decline in maximum stomatal conductance per 100 ppm CO₂ increase, driven by inhibition of meristemoid initiation through EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) signaling.[20] Free-air CO₂ enrichment studies confirm this inverse relationship, with plants like Arabidopsis thaliana exhibiting fewer stomata under doubled ambient CO₂ (around 400 ppm baseline to 800 ppm), enhancing water-use efficiency but potentially limiting carbon assimilation under future climate scenarios.[51] Conversely, sub-ambient CO₂ stimulates higher density, underscoring the role of CO₂ as a key developmental signal.[58] Temperature and water availability exert interactive effects on stomatal ontogeny, with higher temperatures often decreasing density while drought stress can elevate it to maintain conductance.[59] In Quercus robur, warming overrides CO₂ and light effects, reducing stomatal numbers, as evidenced by historical leaf records showing density declines since the 19th century amid rising global temperatures.[60] Drought induces stomatal index increases via abscisic acid-mediated pathways, promoting compact patterning for efficient water retention, though chronic stress may constrain overall development.[61] Humidity gradients similarly influence traits, with low relative humidity fostering higher density in mesophyll-demand driven responses.[54] These abiotic interactions highlight causal linkages to climate variability, with meta-analyses confirming greater responsiveness to light than CO₂ in plasticity rankings.[62]Morphological Diversity

Classification by Type and Arrangement

Stomata are classified primarily by the configuration of their stomatal complexes, which consist of two guard cells and surrounding subsidiary cells derived from the same protodermal lineage. This ontogenetic classification, originally formalized by Florin (1931) and refined in subsequent botanical studies, distinguishes types based on the number, shape, and orientation of subsidiary cells, reflecting evolutionary adaptations and phylogenetic patterns across plant groups.[63][64] The most prevalent types include:- Anomocytic: Guard cells are encircled by ordinary epidermal cells of irregular size and shape, lacking distinct subsidiary cells; common in many dicotyledons such as families Ranunculaceae and Cucurbitaceae.[63][65]

- Anisocytic: Guard cells are flanked by three subsidiary cells, one markedly smaller than the others, forming an unequal arrangement; typical in Brassicaceae (crucifers), Solanaceae, and some monocots.[63][65]

- Paracytic: Guard cells are paralleled by two elongated subsidiary cells oriented longitudinally; widespread in monocotyledons like Poaceae and some dicots such as Rubiaceae.[63][66]

- Tetracytic: Features two lateral subsidiary cells and two polar ones; observed in certain monocots and eudicots like Araceae.[63]

- Diacytic: Guard cells are bookended by two polar subsidiary cells; found in Caryophyllaceae and some Iridaceae.[63]

- Graminaceous: Specialized in grasses, with guard cells subtended by a distinctive flask-shaped subsidiary cell complex derived from a single meristemoid; enables precise control in linear leaves.[63][65]