Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

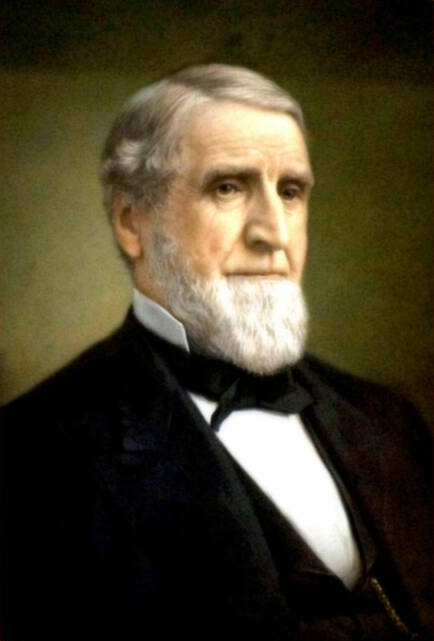

Asa Packer

View on Wikipedia

Asa Packer (December 29, 1805 – May 17, 1879) was an American businessman who pioneered railroad construction, was active in Pennsylvania politics, and founded Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He was a conservative and religious man who reflected the image of the typical Connecticut Yankee. He served two terms in the United States House of Representatives from 1853 to 1857.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Packer was born in Mystic, Connecticut in 1805 and moved to Pennsylvania, where he became a carpenter's apprentice to his cousin Edward Packer in Brooklyn Township, Pennsylvania. He also worked seasonally as a carpenter in New York City and later in Springville Township, Pennsylvania, where he met his wife Sarah Minerva Blakslee.

Early career

[edit]

Packer and his wife settled on a farm. In the winter months, he went to Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River and used his skill in carpentry to build and repair canal boats. This continued for 11 years.[1] In 1833, Packer settled in Mauch Chunk in present-day Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, where he became the owner of a canal boat, which transported anthracite coal from Pennsylvania's Coal Region to Philadelphia. He then established A. & R. W. Packer, a firm that built canal boats and locks for the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company.[2]

Railroad

[edit]Packer urged the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company to adopt a steam railway as a coal carrier, but the project was not then considered feasible.[3] In 1851, he became the major stockholder of the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill & Susquehanna Railroad Company, which became the Lehigh Valley Railroad in January 1853, and they built a railway line from Mauch Chunk to Easton between November 1852 and September 1855.[4] Construction commenced on the Mauch Chunk-Easton line just as Packer's five year charter was to expire.[3] He built railways connecting the main line with coal mines in Luzerne and Schuylkill counties, and he planned and built the extension of the line into the Susquehanna Valley and thence into New York state to connect at Waverly with the Erie Railroad.[2] Among his clerks and associates during this period was future businessman and soldier George Washington Helme.

Politics

[edit]Packer also took an active part in politics. In 1842 and 1843, he was a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. In 1843 and 1844, he was county judge in Carbon County under Governor David R. Porter.

Congress

[edit]He served two terms as a Democratic member of the U.S. House of Representatives beginning in 1853.[2]

1868 Democratic Convention

[edit]George Washington Woodward at the 1868 Democratic National Convention entered Packer's name as a candidate for President as a Favorite son despite himself not being present or actively campaigning. Packer earned a nearly consistent 26 delegates through the 14th round of the ballot and due to him being little known outside of Pennsylvania, with the statement from one delegate; "Who in the hell is Packer?" being used as the headline for many New York journalists, who started to see Packer as an unoffensive moderate candidate that could increase the Democratic party's electability.[5] However, the convention instead went with Horatio Seymour, for largely the same reason but also due to Seymour's name recognition. Interestingly, Woodward attempted to forge a Packer - Blair ticket, however, Francis Preston Blair Jr. was instead named Seymour's running-mate.[6] Packer made an unsuccessful bid for the Democratic Party's Presidential nomination in 1868.

Campaign for governor

[edit]He got the party's nod for the 1869 Pennsylvania Governor's race, but lost the campaign to John W. Geary by 4,596 votes, one of the closest statewide races in Pennsylvania history.

Lehigh University

[edit]Packer endeavored to found a university in the Lehigh Valley, an industrial region located in eastern Pennsylvania.[7] The university was located on South Mountain in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, which then was a Moravian religious community that later became the global manufacturing and corporate headquarters of Bethlehem Steel, the second-largest steel manufacturing company in the world for most of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1865, Packer gave $500,000 and 60 acres (243,000 m²), later increased to 115 acres (465,000 m²), for the establishment of a technical trade school for engineers. In 1866, the year following the end of the American Civil War, the school, named Lehigh University, was chartered and began instruction.[2] The first main building, Packer Hall, was completed in 1869.[8] With Packer's generosity, Lehigh was able to offer education tuition free for its first 20 years from 1871–1891. Economic troubles in the 1890s forced the university to then reverse this policy.

After the initial gift of one half million dollars, Packer continued to support the university and took an active role in its management.[9] His will bequeathed $1,500,000 as an endowment for the university, $500,000 to the university library, and granted the university an interest of nearly one third in his estate upon its final distribution.[2]

Personal life

[edit]Packer was married to Sarah Minerva Blakslee (1807–1882), daughter to Zophar and Clarinda Whitmer Blakslee. The Packers had seven children:

- Lucy Packer Linderman (1832–1873)

- Catherine Packer (1836–1837)

- Mary Hannah Packer Cummings (1839–1912)

- Malvina Fitzrandolph Packer (1841–1841)

- Robert Asa Packer (1842–1883)

- Gertrude Packer (1846–1848)

- Harry Eldred Packer (1850–1884)

Death

[edit]Packer died on May 17, 1879 in Philadelphia, at age 73.[10]

Legacies

[edit]

Packer's residence, Asa Packer Mansion, became a museum, opened for tours in 1956, and was named a National Historic Landmark in 1985. Packer was a member of St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania and contributed large amounts of money to this Gothic Revival Church. St. Mark's was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1987. There is an elementary school in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania named after Packer.

Lehigh University continues to honor him with a large portrait by Charles A. Boutelle and an annual celebration of Founder's Day.[11] A life-sized bronze by Karel Mikolas, donated by the Lehigh University Class of 2003 and dedicated in 2008, stands outside Lehigh University's Alumni Memorial Building.[12] Lehigh Valley Railroad named a passenger train after him, the Asa Packer which ran to and from New York City to Pittston, Pennsylvania until 1959.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Yates 1983, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Packer, Asa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 441–442.

- ^ a b Yates 1983, p. 13.

- ^ "Lehigh Valley Railroad".

- ^ Whelan, Frank. "History's Headlines: Asa Packer, politician". WFMZ-TV. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "President Packer?". scalar.lehigh.edu. Lehigh University. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Yates 1992, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Yates 1983, p. 17.

- ^ Yates 1992, pp. 38–39, 41–42.

- ^ "1879 Obit of Asa Packer". The Allentown Democrat. May 21, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Yates 1983, p. 19.

- ^ Harbrecht, Linda (January 11, 2005). "Asa comes home". Lehigh News. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Yates, W. Ross (1983). Asa Packer: A Perspective (PDF). Bethlehem, PA: Asa Packer Society.

- Yates, W. Ross (1992). Lehigh University : a history of education in engineering, business, and the human condition. Bethlehem Pa: Lehigh University Press. ISBN 978-0-934223-17-1.

- The Asa Packer Mansion Museum.

- Asa Packer at The Political Graveyard

- United States Congress. "Asa Packer (id: P000006)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-03-24

External links

[edit]- Asa Packer letters and ephemera. Available online through Lehigh University's I Remain: A Digital Archive of Letters, Manuscripts, and Ephemera.

- Asa Packer at Find a Grave