Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Astor Opera House

View on Wikipedia40°43′48.5″N 73°59′30.5″W / 40.730139°N 73.991806°W

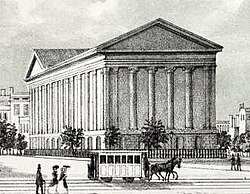

The Astor Opera House, also known as the Astor Place Opera House and later the Astor Place Theatre,[1] was an opera house in Lower Manhattan, New York City, on Lafayette Street between Astor Place and East 8th Street. Designed by Isaiah Rogers (1800–1869), in the Classical Revival style of architecture, inspired by the temples of Ancient Greece and Rome of two thousand years earlier. The theater was conceived by impresario Edward Fry, the brother of composer William Henry Fry (1813–1864), who managed the famed opera house during its entire history.[2][3]

Opera House

[edit]Fry engaged the Sanquerico and Patti Opera Company under the management of John Sefton to perform the first season of opera at the house. The opera house opened on November 22, 1847 with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi's Ernani with Adelino Vietti in the title role.[4] Sefton and his company were not re-engaged by Fry, and the opera management of the house went to Cesare Lietti for the second season. During his tenure the opera house presented the United States premiere of Verdi's Nabucco on April 4, 1848.[5]

Lietti was also replaced after one season, and the Astor's third and longest lasting opera manager, Max Maretzek (1821-1897), was hired for the third season, which commenced in November 1848.[6] The following year Maretzek founded his own opera company, the Max Maretzek Italian Opera Company, with whom he continued to stage operas at the Astor Opera House through to 1852.[7][8] Under Maretzek, the opera house saw the New York premiere of Donizetti's Anna Bolena on January 7, 1850 with soprano Apollonia Bertucca (later Maretzek's wife) as the title heroine.[9]

The theatre was built with the intention of attracting only the "best" patrons, the "uppertens" of New York high society, who were increasingly turning out to see European singers and productions who appeared at local venues such as Niblo's Garden. It was expected that an opera house would be:

a substitute for a general drawing room – a refined attraction which the ill-mannered would not be likely to frequent, and around which the higher classes might gather, for the easier interchange of courtesies, and for that closer view which aides the candidacy of acquaintance.[10]

In pursuit of this agenda, the theatre was created with the comfort of the upper classes in mind: benches, the normal seating in theatres at the time, were replaced by upholstered seats, available only by subscription, as were the two tiers of boxes. On the other hand, 500 general admission patrons were relegated to the benches of a "cockloft" reachable only by a narrow stairway, and otherwise isolated from the gentry below,[3] and the theatre enforced a dress code which required "freshly shaven faces, evening dress, and kid gloves".[11]

Limiting the attendance of the lower classes was partly intended to avoid the problems of rowdyism and hooliganism and common street crime which plagued other theaters in the entertainment district at the time, especially in the theatres further south on the Bowery. Nevertheless, it was the deadly infamous Astor Place Riot, only a year and a half after opening on May 10, 1849 which caused the theatre to close permanently – provoked by competing performances of Macbeth by English actor William Charles Macready (1793–1873), at the Opera House (which was then operating under the name "Astor Place Theatre", not being able to sustain itself on a full season of opera) and American Shakespearean actor Edwin Forrest (1806–1872), at the nearby Broadway Theatre earlier venue of 1889–1929, on 41st Street.

Clinton Hall

[edit]After the riot, the theater was unable to overcome the reputation of being the "Massacre Opera House" at "DisAster Place".[12] By May 1853, the interior had been dismantled and the furnishings sold off, with the shell of the building sold for $140,000[13] to the New York Mercantile Library, which renamed the building "Clinton Hall".[14]

In 1890, in need of additional space, the library tore down the opera house building and replaced it with an 11-story building, also called Clinton Hall, which still stands on the site.[15]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Not the same as the current Astor Place Theatre

- ^ Newman, Nancy (2010). Good Music for a Free People: The Germania Musical Society in Nineteenth-century America. University Rochester Press. p. 40. ISBN 9781580463454.

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 724

- ^ Ireland 1867, p. 515.

- ^ Martin, George Whitney (2011). Verdi in America: Oberto Through Rigoletto. University Rochester Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781580463881.

- ^ Ireland 1867, pp. 515–543.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (November 23, 1969). "Even the Prima Donna Blushed'" (PDF). The New York Times. p. D19.

- ^ Ogasapian, John & Orr, N. Lee (2007). Music of the Gilded Age. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 9780313343094.

- ^ Brodsky Lawrence, Vera (1995). Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton. University of Chicago Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780226470115.

- ^ Nathaniel Parker Willis, quoted in Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 724

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 760.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 765.

- ^ "The Mercantile Library" (PDF). The New York Times. June 1, 1854.

- ^ "Exclusiveness" (PDF). The New York Times. May 27, 1853.

- ^ White & Willensky 2000, p. 162.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- Ireland, Joseph Norton (1867). Records of the New York Stage: from 1750 to 1860. Vol. 2. T. H. Morrell.

- White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Hassard, Jno. [John] R. G. (February 1871). "The New York Mercantile Library", Scribner's Monthly, vol. 1, no. 4. New York: Scribner & Co., pp. 353–367

External links

[edit] Media related to Clinton Hall (former Astor Opera House) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clinton Hall (former Astor Opera House) at Wikimedia Commons

Astor Opera House

View on GrokipediaThe Astor Opera House was a short-lived theater in New York City, conceived by impresario Edward Fry and designed by architect Isaiah Rogers in the Classical Revival style, which opened on November 22, 1847, at 450 Lafayette Street between Astor Place and East 8th Street to host opera and dramatic performances for an elite audience.[1][2][1] The venue enforced exclusionary policies, such as a dress code and reserved boxes for the wealthy, excluding affordable seating for working-class patrons and fueling perceptions of aristocratic exclusivity.[3] Its brief operation ended amid controversy following the Astor Place Riot on May 10, 1849, when clashes between nativist crowds favoring American actor Edwin Forrest and supporters of British performer William Macready during a production of Macbeth escalated into deadly violence, with militia firing on protesters and causing 22 to 31 deaths.[4][5][4] The riot exposed deep class antagonisms and anti-elitist sentiments in mid-19th-century America, leading to the opera house's permanent closure later that year and its eventual demolition in 1890.[1][6]

Origins and Construction

Planning and Funding

The Astor Opera House was conceived in 1847 by impresario Edward Fry amid New York City's burgeoning cultural ambitions and the failure of prior opera ventures, such as Ferdinand Palmo's short-lived opera house that closed in 1844 due to insufficient patronage.[1] Fry, brother of composer William Henry Fry, sought to establish a permanent, elite venue dedicated to Italian grand opera, addressing the city's lack of a suitable theater for such performances while catering to an affluent audience aspiring to European standards.[7] Funding was secured entirely through private enterprise, with approximately 150 prominent New York merchants and elites forming a guarantee fund to underwrite operations for the initial five seasons, ensuring financial stability without reliance on public subsidies.[7] The structure was constructed by the firm of Foster, Morgan, and Colles, reflecting the era's emphasis on subscription-based models where box-holders committed in advance to support the venture's exclusivity and sustainability.[7] The site at the corner of Astor Place and Lafayette Street (originally numbered 13 Astor Place) was chosen for its location in Manhattan's most fashionable residential district, adjacent to elite neighborhoods like Bond Street, to attract high-society patrons and position the opera house as a symbol of New York's emerging rivalry with cultural capitals like London and Paris.[7] This strategic placement underscored the project's aim to foster a refined social space, distinct from more populist theaters downtown.[7]Architectural Design and Features

The Astor Opera House was designed by architect Isaiah Rogers in the Greek Revival style, featuring a trapezoidal plan adapted to the site's angled intersection of Astor Place and Broadway.[8] The facade incorporated a prominent stone portico supported by engaged columns and two-story pilasters on a base of brick and stone, evoking the classical temples of ancient Greece.[7] These elements lent the structure an imperious presence amid the surrounding mansions.[7] Inside, the auditorium adopted a horseshoe-shaped layout with multiple tiers, including a parquet, dress circle, and first tier accommodating approximately 1,100 seats, supplemented by a gallery for 700 more, for a total capacity of around 1,800.[7][9] Private boxes were provided for subscribers, emphasizing social display where patrons could both see and be seen.[7] The interior was lavishly ornamented with moldings and gigantic chandeliers, enhancing the venue's opulence.[9] Construction, completed in 1847, utilized brick and stone materials, which offered some resistance to the frequent urban fires of the period, though the design did not fully eliminate vulnerabilities as evidenced by the building's later history.[7] The layout prioritized visibility across tiers, supporting its function for operatic performances.[7]Operations as Opera House

Opening and Initial Programming

The Astor Opera House opened on November 22, 1847, with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi's Ernani by the Sanquerico and Patti Opera Company, drawing an audience of New York City's affluent elite.[10] [2] This inaugural event marked a deliberate effort to establish grand opera in the European tradition as a cultural institution for the upper class, contrasting with the more populist entertainments prevalent in other New York venues.[7] Under the management of impresario Edward Fry, the initial programming centered on Italian-language operas, with the opening production receiving positive acclaim for its musical quality and production values.[1] [11] Ticket pricing reflected the venue's exclusivity, featuring subscriptions for private boxes reserved for subscribers at premium rates, while parterre and general admission seats—priced around $25 to $30 for tiered options—remained prohibitive for working-class patrons compared to standard theater admissions elsewhere.[9] From the outset, operational challenges arose due to the high costs of importing European performers and staging elaborate productions, compounded by competition from affordable, English-language theaters like the Bowery, which catered to broader audiences with native talent and lower prices.[7] These factors underscored early tensions between fostering an aristocratic opera culture and the realities of public demand in a diverse, rapidly growing city, though the first season proved modestly successful among its target demographic.[11]Key Performances and Management

Under the management of impresario Edward Fry, the Astor Place Opera House prioritized Italian opera and refined dramatic presentations aimed at an elite audience, with ticket prices set high—ranging from $1 to $3 per seat—to exclude lower-class patrons and mitigate disruptions common in more democratic theaters.[12] Fry's brother, composer William Henry Fry, influenced programming toward elevated cultural offerings, though no works by the latter were staged during this period, reflecting a focus on established European repertory over nascent American compositions.[13] This approach fostered an atmosphere of exclusivity but alienated broader public interest, as evidenced by policies against rowdy behavior that reinforced social barriers between the "uppertens" and working-class theatergoers.[12] Significant productions included the United States premiere of Giuseppe Verdi's Nabucco on April 4, 1848, featuring an Italian company assembled by Fry, which highlighted the venue's role in introducing contemporary European operas to American audiences.[14] The repertory also encompassed other Italian works by Verdi and Donizetti, alongside occasional English-language plays such as Shakespearean dramas, broadening appeal slightly while maintaining an emphasis on operatic sophistication over popular spectacles.[15] These engagements drew acclaim for artistic quality but struggled with inconsistent attendance beyond affluent subscribers, underscoring class-based divides in cultural access.[11] Operational challenges mounted due to financial shortfalls, with low turnout outside elite circles exacerbating deficits despite the house's capacity for 1,800 patrons; by spring 1849, these pressures contributed to Fry's departure amid mounting losses.[11] The insistence on refined patronage, while preserving decorum, limited revenue streams in a city where mass-appeal entertainments thrived elsewhere, signaling the unsustainability of the model before the theater's pivot to dramatic rentals.[13]The Astor Place Riot

Underlying Rivalries and Tensions

The personal rivalry between American actor Edwin Forrest and British tragedian William Macready, which simmered for years before erupting in 1849, centered on contrasting interpretations of Shakespearean roles and escalated through mutual public disruptions. Forrest, known for his vigorous, physically emphatic style emblematic of native American vigor, clashed with Macready's precise, intellectually restrained approach associated with British theatrical tradition. The feud ignited during Forrest's 1845–1846 tour of England, where he hissed Macready's Hamlet over a perceived frivolous "fancy dance," and intensified when Forrest hissed Macready during a March 1846 performance in Edinburgh, an act defended in contemporary British press as a response to prior hostilities.[16] [17] By late 1848, Forrest scheduled competing performances of the same roles as Macready in U.S. cities like Philadelphia, prompting audiences to hurl objects at Macready and amplifying perceptions of deliberate sabotage.[16] This actorly antagonism symbolized deeper nativist resentments against perceived British cultural dominance, rooted in lingering animosities from the War of 1812 and the era's push for American artistic independence. Forrest positioned himself as a defender of robust, indigenous drama against what supporters decried as aristocratic importation, viewing Macready's 1849 New York engagement as an extension of cultural imperialism by elite Anglophiles.[17] [4] Anti-British theater sentiments, treating Shakespearean performance as a foreign imposition, fueled backlash among nativists skeptical of European refinement amid post-war assertions of U.S. exceptionalism.[18] Macready, praised by affluent patrons as a paragon of sophistication, embodied for critics the elitism of "princes' pets," exacerbating divides between working-class nationalists and the pro-British upper strata.[4] While class resentments contributed—working-class theatergoers at venues like the Bowery chafed at the Astor Opera House's exclusivity for the "Upper Ten" thousand wealthiest—mobilization emphasized American nationalism over proletarian grievance alone. Handbills distributed by figures like Isaiah Rynders and Edward Z. C. Judson ("Ned Buntline") rallied Forrest's backers with appeals such as "Working Men, Shall Americans or English Rule in This City?", framing opposition as a patriotic stand against foreign rule rather than mere economic envy.[17] [19] These broadsides, invoking threats from a supposed "British steamer" crew to free speech at the "Aristocratic Opera House," harnessed nativist fervor to organize crowds, underscoring how national identity trumped class solidarity in stoking pre-riot agitation.[19]Sequence of Events

On May 7, 1849, William Charles Macready's performance of Macbeth at the Astor Opera House was disrupted by approximately 500 organized agitators who hissed, yelled, and hurled objects including rotten eggs, pennies, and chairs at the stage, compelling Macready to halt the show and withdraw temporarily.[15] No arrests occurred owing to the disruptors' numbers and the risk to the audience, which included women.[15] Macready proceeded with a scheduled encore performance of Macbeth on May 10, leading city officials, including Mayor Caleb S. Woodhull, to deploy protective forces comprising 210 militiamen from the 7th Regiment National Guard under General Sandford and around 200 policemen.[15][20] By evening on May 10, a mob numbering 10,000 to 20,000 had mobilized outside the theater, shouting anti-British and anti-aristocratic epithets while pelting the structure with paving stones that shattered windows and splintered barricades.[15][21] The initial cavalry charge faltered under a barrage of stones, after which infantry lines endured sustained stone volleys that wounded multiple soldiers and officers, including Captain Elijah Shumway.[15] Following verbal warnings to disperse, the militia discharged volleys—first aimed overhead and then directed lower into the crowd—prompting rioters to storm the building and inflict partial interior damage before order was restored.[15][22]Immediate Aftermath and Casualties

The Astor Place Riot on May 10, 1849, resulted in 22 to 31 deaths, predominantly among working-class participants in the crowd, with over 120 others injured from gunfire and melee.[21] [4] [20] A coroner's jury investigation determined that the fatalities stemmed from gunshot wounds inflicted by state militia volleys, ordered after the crowd overwhelmed police lines, pelted the opera house with stones, and attempted to seize soldiers' weapons.[5] This military response, while effective in dispersing the mob, highlighted the perils of escalating crowd unrest where initial theatrical protests devolved into physical assault on authorities and property.[21] Approximately 60 rioters were arrested in the immediate aftermath, with around 10 subsequently indicted on charges of incitement and disorderly conduct.[20] Prominent figures like Edward Z. C. Judson, known as Ned Buntline and a vocal nativist agitator who had distributed inflammatory handbills favoring American actor Edwin Forrest over British performer William Macready, faced trial for misdemeanor incitement.[20] Judson was convicted on September 29, 1849, and sentenced to one year in prison plus a $250 fine, though he garnered sympathy from nativist circles viewing the proceedings as suppression of anti-aristocratic sentiment; associate Isaiah Rynders, another instigator, was acquitted.[20] [23] The legal proceedings underscored tensions between protecting public order and permitting expressive grievances, but prioritized accountability for direct provocation amid evidence of organized rallying cries and weaponized protest.[5] The opera house was shuttered temporarily following the violence, with damaged interiors—including shattered windows and barricades—prompting immediate repairs and elite patrons' demands for enhanced policing at such venues to prevent recurrence of mob incursions driven by unchecked escalation rather than purely ideological orchestration.[1] This scrutiny reflected broader short-term repercussions, as authorities reinforced that crowd dynamics, fueled by nativist fervor against perceived cultural elitism, had crossed into threats warranting lethal force only after non-lethal measures failed.[17]Closure and Repurposing

Factors Leading to Shutdown

The Astor Place Opera House faced chronic financial deficits from its inception in 1847, stemming from exorbitant operational costs associated with importing European opera troupes and staging lavish Italian productions primarily for an elite clientele. With seating limited to 1,100 patrons and ticket prices set at $1 (equivalent to about $25 in modern terms), the venue catered exclusively to New York's upper class, restricting its audience base and failing to generate sufficient revenue to offset high overheads like performer salaries and maintenance of its opulent interior. Guarantees from 150 prominent subscribers for five years of support proved inadequate against these structural imbalances, as the house struggled to attract broader attendance in a city where opera remained a nascent import rather than a mass entertainment.[7] The Astor Place Riot of May 10, 1849, intensified these woes by inflicting reputational harm that deterred subscribers and amplified public aversion to the venue. Dubbed the "Massacre Opera House" in contemporary burlesques and press accounts, the site became synonymous with class violence and elite detachment, leading patrons to shun it amid lingering associations with the deaths of up to 25 individuals and injuries to 120 more during the clashes outside. This shift eroded the house's prestige, exacerbating subscriber boycotts and revenue shortfalls, as working-class New Yorkers viewed it as a symbol of aristocratic exclusion while elites sought safer alternatives.[24][7] Managerial shortcomings in adapting to America's emerging theater market further sealed its fate, as operators like Edward R. Fry prioritized rigid exclusivity over populist appeal, unable to compete with cheaper, more accessible venues offering diverse entertainments. By 1852, these cumulative pressures—compounded by incidents like rival promoter William Niblo's 1852 dog show that mocked the house's aristocratic pretensions—rendered sustained opera programming unviable, prompting a pivot away from performances altogether. This reflected wider challenges in transplanting costly European opera traditions to a democratizing U.S. audience preferring affordable spectacles over highbrow imports.[7]Conversion to Clinton Hall

In May 1854, the Clinton Hall Association purchased the former Astor Opera House for $140,000 and allocated an additional $115,000 to modify the interior into reading rooms, lecture halls, meeting spaces, and storage for the Mercantile Library Association, retaining the exterior facade while adapting the structure away from theatrical functions.[7]

The renamed Clinton Hall honored former New York Governor DeWitt Clinton and opened as a key resource for middle-class intellectual pursuits, broadening library membership beyond merchants.[25][26]

By the 1870s, the library's holdings exceeded 120,000 volumes, supporting daily circulation of up to 1,000 books and establishing it as the nation's largest lending library.[25]

The venue facilitated educational programming, including lectures by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain alongside classes in chemistry and languages, underscoring effective repurposing for non-entertainment uses during New York City's commercial expansion.[25]