Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Astronomical rings

View on Wikipedia

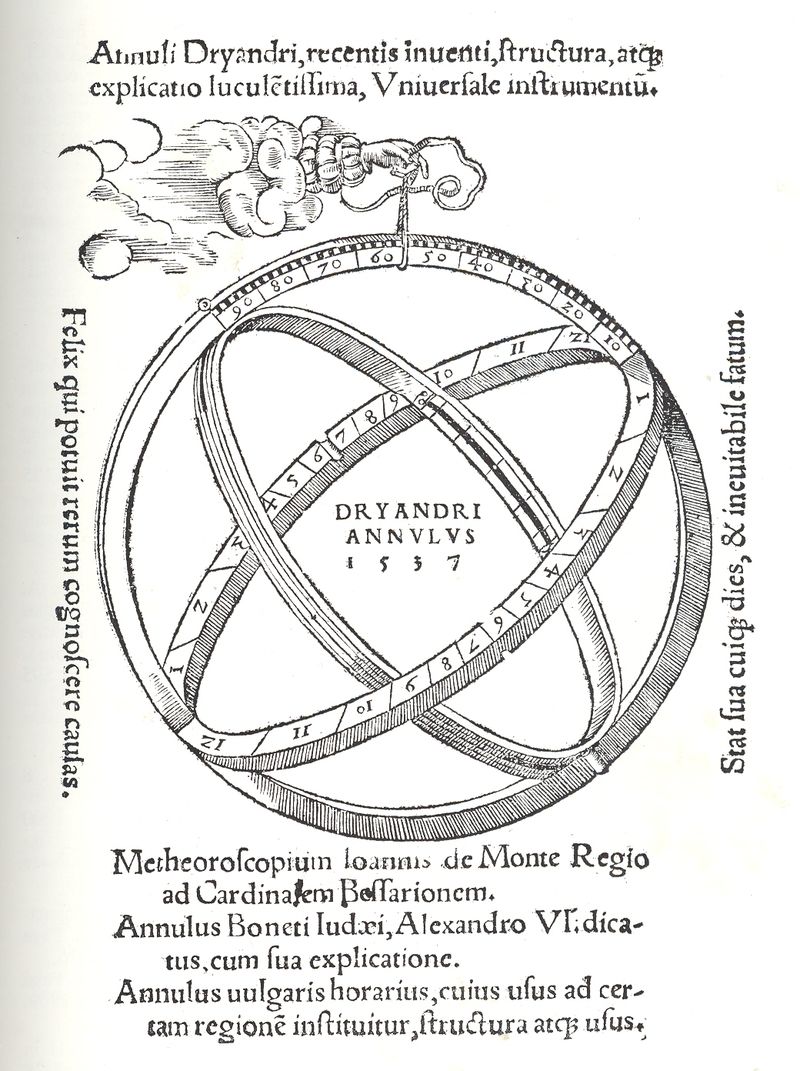

Astronomical rings (Latin: annuli astronomici),[1] also known as Gemma's rings, are an early astronomical instrument. The instrument consists of three rings, representing the celestial equator, declination, and the meridian.

It can be used as a sun dial to tell time, if the approximate latitude and season is known, or to tell latitude, if the time is known or observed (at solar noon). It may be considered to be a simplified, portable armillary sphere, or a more complex form of astrolabe.

History

[edit]Parts of the instrument go back to instruments made and used by ancient Greek astronomers. Gemma Frisius combined several of the instruments into a small, portable, astronomical-ring instrument. He first published the design in 1534,[2] and in Petrus Apianus's Cosmographia in 1539. These ring instruments combined terrestrial and celestial calculations.[3]

Types

[edit]Fixed astronomical rings

[edit]

Fixed astronomical rings are mounted on a plinth, like armillary spheres, and can be used as sundials.

Traveller's sundial or universal equinoctal ring dial

[edit]The dial is suspended from a cord or chain; the suspension point on the vertical meridian ring can be changed to match the local latitude. The time is read off on the equatorial ring; in the example below, the center bar is twisted until a sunray passes through a small hole and falls on the horizontal equatorial ring.

-

Traveller's sundial or universal ring dial, a portable version of astronomical rings, closed for carrying.

-

Traveller's sundial, open, ready for use. See Commons annotations for labels of parts of the traveller's sundial.

-

Traveller's sundial, in use, with position of light beam (inside highlighting square) being read off to tell the time. See annotations for how to read the sundial.

Sun ring

[edit]A sunring or farmer's ring is a latitude-specific simplification of astronomical rings. On one-piece sunrings, the time and month scale is marked on the inside of the ring; a sunbeam passing through a hole in the ring lights a point on this scale. Newer sunrings are often made in two parts, one of which slides to set the month; they are usually less accurate.

-

Diagram of a one-part sunring, with sunbeam

-

A two-part sunring or farmer's ring, with light beam showing the time

-

A simpler sundial ring, not in use

Sea ring

[edit]

In 1610, Edward Wright created the sea ring, which mounted a universal ring dial over a magnetic compass. This permitted mariners to determine the time and magnetic variation in a single step.[4] These are also called "sundial compasses".

Structure and function

[edit]The three rings are oriented with respect to the local meridian, the planet's equator, and a celestial object. The instrument itself can be used as a plumb bob to align it with the vertical. The instrument is then rotated until a single light beam passes through two points on the instrument. This fixes the orientation of the instrument in all three axes.

The angle between the vertical and the light beam gives the solar elevation. The solar elevation is a function of latitude, time of day, and season. Any one of these variables can be determined using astronomical rings, if the other two are known.

The altitude of the sun does not change much in a single day at the poles (where the sun rises and sets once a year), so rough measurements of solar altitude don't vary with time of day at high latitudes.

Use as a calendar sundial

[edit]When the solar time is exactly noon, or known from another clock, the instrument can be used to determine the time of year.

The meridional ring can function as the gnomon, when the rings are used as a sundial. A horizontal line aligned on a meridian with a gnomon facing the noon-sun is termed a meridian line and does not indicate the time, but instead the day of the year. Historically they were used to accurately determine the length of the solar year. A fixed meridional ring on its own can be used as an analemma calendar sundial, which can be read only at noon.

When the shadow of the rings are aligned so that they appear to be in the same, or nearly the same, place, the meridian identifies itself.[clarification needed]

Meridional ring

[edit]The meridian ring is placed vertically, then rotated (relative to the celestial object) until it is parallel to the local north-south line. The whole ring is thus parallel to the circle of longitude passing through the place where the user is standing.

Because the instrument is often supported by the meridional ring, it is often the outermost ring, as it is in the traveller's rings illustrated above. There, a sliding suspension shackle is attached to the top of the meridional ring, from which the whole device can be suspended. The meridional ring is marked in degrees of latitude (0–90, for each hemisphere). When properly used, the pointer on the support points to the latitude of the instrument's location. This tilts the equatorial ring so that it lies at the same angle to the vertical as the local equator.[5][6]

Equatorial ring

[edit]The equatorial ring occupies a plane parallel to the celestial equator, at right angles to the meridian. It is aligned by

- being attached to the meridional ring at the marking for latitude zero (see above)

- being aligned to the declension ring, which is aligned to the celestial object.

Often equipped with a graduated scale, it can be used to measure right ascension. On the traveller's sundial shown above, it is the inner ring.

This ring is sometimes engraved with the months on one side and corresponding zodiac signs on the outside; very similar to an astrolabe. Others have been found to be engraved with two twelve-hour time scales. Each twelve-hour scale is stretched over 180 degrees and numbered by hour with hashes every 20 minutes and smaller hashes every four minutes. The inside displays a calendrical scale with the names of the months indicated by their first letters, with a mark to show every 5 days and other marks to represent single days. On these, the outside of the ring is engraved with the corresponding symbols of the zodiac signs. The position of the symbol indicates the date of the entry of the sun into this particular sign. The vernal equinox is marked at March 15 and the autumnal equinox is marked at September 10.[7]

Declination ring

[edit]

The declination ring is moveable, and rotates on pivots set in the meridian ring. An imaginary line connecting these pivots is parallel to the Earth's axis. The declination "ring" of the traveller's sundial above is not a ring at all, but an oblong loop with a slider for setting the season.

This ring is often equipped with vanes and pinholes for use as the alidade of a dioptra (see image). It can be used to measure declination.

This ring is also often marked with the zodiac signs and twenty-five stars, similar to the astrolabe.

References

[edit]- ^ "Annulus Astronomicus". Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Sorgeloos, Claude (2001). "Un post-incunable retrouvé : L'Usus annuli astronomici de Gemma Frisius, Louvain et Anvers, 1534" [A post-incunabula discovery: 'The use of astronomical rings' by Gemma Frisius]. Quaerendo (in French). 31 (4). Leiden: 255–264. doi:10.1163/157006901X00155. ISSN 0014-9527. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Wallis, Helen (1984). "England's Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries". Arctic. 37 (4): 453–472. doi:10.14430/arctic2228. JSTOR 40510308.

- ^ May, William Edward, A History of Marine Navigation, G. T. Foulis & Co. Ltd., Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, 1973, ISBN 0-85429-143-1

- ^ "Collection". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ "Mid 18th Century Brass Astronomical ring dial. - Gilai Collectibles".

- ^ "Astronomical dial; ring-dial; sundial | British Museum". Archived from the original on 2013-11-12.

Bibliography

[edit]- Frisius, Gemma (1548). Usus annuli astronomici [The Use of the Astronomical Rings] (digital reprint) (in Latin). Antwerp. OCLC 166113158.