Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sundial

View on Wikipedia

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat plate (the dial) and a gnomon, which casts a shadow onto the dial. As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day. The style is the time-telling edge of the gnomon, though a single point or nodus may be used. The gnomon casts a broad shadow; the shadow of the style shows the time. The gnomon may be a rod, wire, or elaborately decorated metal casting. The style must be parallel to the axis of the Earth's rotation for the sundial to be accurate throughout the year. The style's angle from horizontal is equal to the sundial's geographical latitude.

The term sundial can refer to any device that uses the Sun's altitude or azimuth (or both) to show the time. Sundials are valued as decorative objects, metaphors, and objects of intrigue and mathematical study.

The passing of time can be observed by placing a stick in the sand or a nail in a board and placing markers at the edge of a shadow or outlining a shadow at intervals. It is common for inexpensive, mass-produced decorative sundials to have incorrectly aligned gnomons, shadow lengths, and hour-lines, which cannot be adjusted to tell the correct time.[2]

Introduction

[edit]There are several different types of sundials. Some sundials use a shadow or the edge of a shadow while others use a line or spot of light to indicate the time.

The shadow-casting object, known as a gnomon, may be a long thin rod or other object with a sharp tip or a straight edge. Sundials employ many types of gnomon. The gnomon may be fixed or moved according to the season. It may be oriented vertically, horizontally, aligned with the Earth's axis, or oriented in an altogether different direction determined by mathematics.

Given that sundials use light to indicate time, a line of light may be formed by allowing the Sun's rays through a thin slit or focusing them through a cylindrical lens. A spot of light may be formed by allowing the Sun's rays to pass through a small hole, window, oculus, or by reflecting them from a small circular mirror. A spot of light can be as small as a pinhole in a solargraph or as large as the oculus in the Pantheon.

Sundials may also use many types of surfaces to receive the light or shadow. Planes are the most common surface, but partial spheres, cylinders, cones and other shapes have been used for greater accuracy or beauty.

Sundials differ in their portability and their need for orientation. The installation of many dials requires knowing the local latitude, the precise vertical direction (e.g., by a level or plumb-bob), and the direction to true north. Portable dials are self-aligning: for example, they may have two dials that operate on different principles, such as a horizontal and analemmatic dial, mounted together on one plate. In these designs, their times agree only when the plate is aligned properly. [3]

Sundials may indicate the local solar time only. To obtain the national clock time, three corrections are required:

- The orbit of the Earth is not perfectly circular and its rotational axis is not perpendicular to its orbit. The sundial's indicated solar time thus varies from clock time by small amounts that change throughout the year. This correction—which may be as great as 16 minutes, 33 seconds—is described by the equation of time. A sophisticated sundial, with a curved style or hour lines, may incorporate this correction. The more usual simpler sundials sometimes have a small plaque that gives the offsets at various times of the year.

- The solar time must be corrected for the longitude of the sundial relative to the longitude of the official time zone. For example, an uncorrected sundial located west of Greenwich, England but within the same time-zone, shows an earlier time than the official time. It may show "11:45" at official noon, and will show "noon" after the official noon. This correction can easily be made by rotating the hour-lines by a constant angle equal to the difference in longitudes, which makes this a commonly possible design option.

- To adjust for daylight saving time, if applicable, the solar time must additionally be shifted for the official difference (usually one hour). This is also a correction that can be done on the dial, i.e. by numbering the hour-lines with two sets of numbers, or even by swapping the numbering in some designs. More often this is simply ignored, or mentioned on the plaque with the other corrections, if there is one.

Apparent motion of the Sun

[edit]

The principles of sundials are understood most easily from the Sun's apparent motion.[4] The Earth rotates on its axis, and revolves in an elliptical orbit around the Sun. An excellent approximation assumes that the Sun revolves around a stationary Earth on the celestial sphere, which rotates every 24 hours about its celestial axis. The celestial axis is the line connecting the celestial poles. Since the celestial axis is aligned with the axis about which the Earth rotates, the angle of the axis with the local horizontal is the local geographical latitude.

Unlike the fixed stars, the Sun changes its position on the celestial sphere, being (in the Northern Hemisphere) at a positive declination in spring and summer, and at a negative declination in autumn and winter, and having exactly zero declination (i.e., being on the celestial equator) at the equinoxes. The Sun's celestial longitude also varies, changing by one complete revolution per year. The path of the Sun on the celestial sphere is called the ecliptic. The ecliptic passes through the twelve constellations of the zodiac in the course of a year.

This model of the Sun's motion helps to understand sundials. If the shadow-casting gnomon is aligned with the celestial poles, its shadow will revolve at a constant rate, and this rotation will not change with the seasons. This is the most common design. In such cases, the same hour lines may be used throughout the year. The hour-lines will be spaced uniformly if the surface receiving the shadow is either perpendicular (as in the equatorial sundial) or circular about the gnomon (as in the armillary sphere).

In other cases, the hour-lines are not spaced evenly, even though the shadow rotates uniformly. If the gnomon is not aligned with the celestial poles, even its shadow will not rotate uniformly, and the hour lines must be corrected accordingly. The rays of light that graze the tip of a gnomon, or which pass through a small hole, or reflect from a small mirror, trace out a cone aligned with the celestial poles. The corresponding light-spot or shadow-tip, if it falls onto a flat surface, will trace out a conic section, such as a hyperbola, ellipse or (at the North or South Poles) a circle.

This conic section is the intersection of the cone of light rays with the flat surface. This cone and its conic section change with the seasons, as the Sun's declination changes; hence, sundials that follow the motion of such light-spots or shadow-tips often have different hour-lines for different times of the year. This is seen in shepherd's dials, sundial rings, and vertical gnomons such as obelisks. Alternatively, sundials may change the angle or position (or both) of the gnomon relative to the hour lines, as in the analemmatic dial or the Lambert dial.

History

[edit]

The earliest sundials known from the archaeological record are shadow clocks (1500 BC or BCE) from ancient Egyptian astronomy and Babylonian astronomy. By 240 BC, Eratosthenes had estimated the circumference of the world using an obelisk and a water well and a few centuries later, Ptolemy had charted the latitude of cities using the angle of the sun. The people of Kush created sun dials through geometry.[5][6] The Roman writer Vitruvius lists dials and shadow clocks known at that time in his De architectura. The Tower of the Winds in Athens included both a sundial and a water clock for telling time. A canonical sundial is one that indicates the canonical hours of liturgical acts, and these were used from the 7th to the 14th centuries by religious orders. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Padovani published a treatise on the sundial in 1570, in which he included instructions for the manufacture and laying out of mural (vertical) and horizontal sundials. Giuseppe Biancani's Constructio instrumenti ad horologia solaria (c. 1620) discusses how to make a perfect sundial. They have been in common use since the 16th century.

Functioning

[edit]

In general, sundials indicate the time by casting a shadow or throwing light onto a surface known as a dial face or dial plate. Although usually a flat plane, the dial face may also be the inner or outer surface of a sphere, cylinder, cone, helix, and various other shapes.

The time is indicated where a shadow or light falls on the dial face, which is usually inscribed with hour lines. Although usually straight, these hour lines may also be curved, depending on the design of the sundial (see below). In some designs, it is possible to determine the date of the year, or it may be required to know the date to find the correct time. In such cases, there may be multiple sets of hour lines for different months, or there may be mechanisms for setting/calculating the month. In addition to the hour lines, the dial face may offer other data—such as the horizon, the equator and the tropics—which are referred to collectively as the dial furniture.

The entire object that casts a shadow or light onto the dial face is known as the sundial's gnomon.[7] However, it is usually only an edge of the gnomon (or another linear feature) that casts the shadow used to determine the time; this linear feature is known as the sundial's style. The style is usually aligned parallel to the axis of the celestial sphere, and therefore is aligned with the local geographical meridian. In some sundial designs, only a point-like feature, such as the tip of the style, is used to determine the time and date; this point-like feature is known as the sundial's nodus.[7][a] Some sundials use both a style and a nodus to determine the time and date.

The gnomon is usually fixed relative to the dial face, but not always; in some designs such as the analemmatic sundial, the style is moved according to the month. If the style is fixed, the line on the dial plate perpendicularly beneath the style is called the substyle,[7] meaning "below the style". The angle the style makes with the plane of the dial plate is called the substyle height, an unusual use of the word height to mean an angle. On many wall dials, the substyle is not the same as the noon line (see below). The angle on the dial plate between the noon line and the substyle is called the substyle distance, an unusual use of the word distance to mean an angle.

By tradition, many sundials have a motto. The motto is usually in the form of an epigram: sometimes sombre reflections on the passing of time and the brevity of life, but equally often humorous witticisms of the dial maker. One such quip is, I am a sundial, and I make a botch, Of what is done much better by a watch.[8]

A dial is said to be equiangular if its hour-lines are straight and spaced equally. Most equiangular sundials have a fixed gnomon style aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, as well as a shadow-receiving surface that is symmetrical about that axis; examples include the equatorial dial, the equatorial bow, the armillary sphere, the cylindrical dial and the conical dial. However, other designs are equiangular, such as the Lambert dial, a version of the analemmatic sundial with a moveable style.

In the Southern Hemisphere

[edit]

A sundial at a particular latitude in one hemisphere must be reversed for use at the opposite latitude in the other hemisphere.[9] A vertical direct south sundial in the Northern Hemisphere becomes a vertical direct north sundial in the Southern Hemisphere. To position a horizontal sundial correctly, one has to find true north or south. The same process can be used to do both.[10] The gnomon, set to the correct latitude, has to point to the true south in the Southern Hemisphere as in the Northern Hemisphere it has to point to the true north.[11] The hour numbers also run in opposite directions, so on a horizontal dial they run anticlockwise (US: counterclockwise) rather than clockwise.[12]

Sundials which are designed to be used with their plates horizontal in one hemisphere can be used with their plates vertical at the complementary latitude in the other hemisphere. For example, the illustrated sundial in Perth, Australia, which is at latitude 32° South, would function properly if it were mounted on a south-facing vertical wall at latitude 58° (i.e. 90° − 32°) North, which is slightly further north than Perth, Scotland. The surface of the wall in Scotland would be parallel with the horizontal ground in Australia (ignoring the difference of longitude), so the sundial would work identically on both surfaces. Correspondingly, the hour marks, which run counterclockwise on a horizontal sundial in the Southern Hemisphere, also do so on a vertical sundial in the Northern Hemisphere. (See the first two illustrations at the top of this article.) On horizontal Northern Hemisphere sundials, and on vertical Southern Hemisphere ones, the hour marks run clockwise.

Adjustments to calculate clock time from a sundial reading

[edit]The most common reason for a sundial to differ greatly from clock time is that the sundial has not been oriented correctly or its hour lines have not been drawn correctly. For example, most commercial sundials are designed as horizontal sundials as described above. To be accurate, such a sundial must have been designed for the local geographical latitude and its style must be parallel to the Earth's rotational axis; the style must be aligned with true north and its height (its angle with the horizontal) must equal the local latitude. To adjust the style height, the sundial can often be tilted slightly "up" or "down" while maintaining the style's north-south alignment.[13]

Summer (daylight saving) time correction

[edit]Some areas of the world practice daylight saving time, which changes the official time, usually by one hour. This shift must be added to the sundial's time to make it agree with the official time.

Time-zone (longitude) correction

[edit]A standard time zone covers roughly 15° of longitude, so any point within that zone which is not on the reference longitude (generally a multiple of 15°) will experience a difference from standard time that is equal to 4 minutes of time per degree. For illustration, sunsets and sunrises are at a much later "official" time at the western edge of a time-zone, compared to sunrise and sunset times at the eastern edge. If a sundial is located at, say, a longitude 5° west of the reference longitude, then its time will read 20 minutes slow, since the Sun appears to revolve around the Earth at 15° per hour. This is a constant correction throughout the year. For equiangular dials such as equatorial, spherical or Lambert dials, this correction can be made by rotating the dial surface by an angle equaling the difference in longitude, without changing the gnomon position or orientation. However, this method does not work for other dials, such as a horizontal dial; the correction must be applied by the viewer.

However, for political and practical reasons, time-zone boundaries have been skewed. At their most extreme, time zones can cause official noon, including daylight savings, to occur up to three hours early (in which case the Sun is actually on the meridian at official clock time of 3 PM). This occurs in the far west of Alaska, China, and Spain. For more details and examples, see time zones.

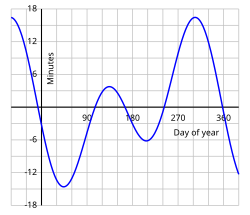

Equation of time correction

[edit]

Although the Sun appears to rotate uniformly about the Earth, in reality this motion is not perfectly uniform. This is due to the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit (the fact that the Earth's orbit about the Sun is not perfectly circular, but slightly elliptical) and the tilt (obliquity) of the Earth's rotational axis relative to the plane of its orbit. Therefore, sundial time varies from standard clock time. On four days of the year, the correction is effectively zero. However, on others, it can be as much as a quarter-hour early or late. The amount of correction is described by the equation of time. This correction is equal worldwide: it does not depend on the local latitude or longitude of the observer's position. It does, however, change over long periods of time, (centuries or more,[14]) because of slow variations in the Earth's orbital and rotational motions. Therefore, tables and graphs of the equation of time that were made centuries ago are now significantly incorrect. The reading of an old sundial should be corrected by applying the present-day equation of time, not one from the period when the dial was made.

In some sundials, the equation of time correction is provided as an informational plaque affixed to the sundial, for the observer to calculate. In more sophisticated sundials the equation can be incorporated automatically. For example, some equatorial bow sundials are supplied with a small wheel that sets the time of year; this wheel in turn rotates the equatorial bow, offsetting its time measurement. In other cases, the hour lines may be curved, or the equatorial bow may be shaped like a vase, which exploits the changing altitude of the sun over the year to effect the proper offset in time.[15]

A heliochronometer is a precision sundial first devised in about 1763 by Philipp Hahn and improved by Abbé Guyoux in about 1827.[16] It corrects apparent solar time to mean solar time or another standard time. Heliochronometers usually indicate the minutes to within 1 minute of Universal Time.

The Sunquest sundial, designed by Richard L. Schmoyer in the 1950s, uses an analemmic-inspired gnomon to cast a shaft of light onto an equatorial time-scale crescent. Sunquest is adjustable for latitude and longitude, automatically correcting for the equation of time, rendering it "as accurate as most pocket watches".[17][18][19][20]

Similarly, in place of the shadow of a gnomon the sundial at Miguel Hernández University uses the solar projection of a graph of the equation of time intersecting a time scale to display clock time directly.

An analemma may be added to many types of sundials to correct apparent solar time to mean solar time or another standard time. These usually have hour lines shaped like "figure eights" (analemmas) according to the equation of time. This compensates for the slight eccentricity in the Earth's orbit and the tilt of the Earth's axis that causes up to a 15 minute variation from mean solar time. This is a type of dial furniture seen on more complicated horizontal and vertical dials.

Prior to the invention of accurate clocks, in the mid 17th century, sundials were the only timepieces in common use, and were considered to tell the "right" time. The equation of time was not used. After the invention of good clocks, sundials were still considered to be correct, and clocks usually incorrect. The equation of time was used in the opposite direction from today, to apply a correction to the time shown by a clock to make it agree with sundial time. Some elaborate "equation clocks", such as one made by Joseph Williamson in 1720, incorporated mechanisms to do this correction automatically. (Williamson's clock may have been the first-ever device to use a differential gear.) Only after about 1800 was uncorrected clock time considered to be "right", and sundial time usually "wrong", so the equation of time became used as it is today.[21]

With fixed axial gnomon

[edit]The most commonly observed sundials are those in which the shadow-casting style is fixed in position and aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, being oriented with true north and south, and making an angle with the horizontal equal to the geographical latitude. This axis is aligned with the celestial poles, which is closely, but not perfectly, aligned with the pole star Polaris. For illustration, the celestial axis points vertically at the true North Pole, whereas it points horizontally on the equator. The world's largest axial gnomon sundial is the mast of the Sundial Bridge at Turtle Bay in Redding, California . A formerly world's largest gnomon is at Jaipur, raised 26°55′ above horizontal, reflecting the local latitude.[22]

On any given day, the Sun appears to rotate uniformly about this axis, at about 15° per hour, making a full circuit (360°) in 24 hours. A linear gnomon aligned with this axis will cast a sheet of shadow (a half-plane) that, falling opposite to the Sun, likewise rotates about the celestial axis at 15° per hour. The shadow is seen by falling on a receiving surface that is usually flat, but which may be spherical, cylindrical, conical or of other shapes. If the shadow falls on a surface that is symmetrical about the celestial axis (as in an armillary sphere, or an equatorial dial), the surface-shadow likewise moves uniformly; the hour-lines on the sundial are equally spaced. However, if the receiving surface is not symmetrical (as in most horizontal sundials), the surface shadow generally moves non-uniformly and the hour-lines are not equally spaced; one exception is the Lambert dial described below.

Some types of sundials are designed with a fixed gnomon that is not aligned with the celestial poles like a vertical obelisk. Such sundials are covered below under the section, "Nodus-based sundials".

Empirical hour-line marking

[edit]The formulas shown in the paragraphs below allow the positions of the hour-lines to be calculated for various types of sundial. In some cases, the calculations are simple; in others they are extremely complicated. There is an alternative, simple method of finding the positions of the hour-lines which can be used for many types of sundial, and saves a lot of work in cases where the calculations are complex.[23] This is an empirical procedure in which the position of the shadow of the gnomon of a real sundial is marked at hourly intervals. The equation of time must be taken into account to ensure that the positions of the hour-lines are independent of the time of year when they are marked. An easy way to do this is to set a clock or watch so it shows "sundial time"[b] which is standard time,[c] plus the equation of time on the day in question.[d] The hour-lines on the sundial are marked to show the positions of the shadow of the style when this clock shows whole numbers of hours, and are labelled with these numbers of hours. For example, when the clock reads 5:00, the shadow of the style is marked, and labelled "5" (or "V" in Roman numerals). If the hour-lines are not all marked in a single day, the clock must be adjusted every day or two to take account of the variation of the equation of time.

Equatorial sundials

[edit]

The distinguishing characteristic of the equatorial dial (also called the equinoctial dial) is the planar surface that receives the shadow, which is exactly perpendicular to the gnomon's style.[26] This plane is called equatorial, because it is parallel to the equator of the Earth and of the celestial sphere. If the gnomon is fixed and aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, the sun's apparent rotation about the Earth casts a uniformly rotating sheet of shadow from the gnomon; this produces a uniformly rotating line of shadow on the equatorial plane. Since the Earth rotates 360° in 24 hours, the hour-lines on an equatorial dial are all spaced 15° apart (360/24).

The uniformity of their spacing makes this type of sundial easy to construct. If the dial plate material is opaque, both sides of the equatorial dial must be marked, since the shadow will be cast from below in winter and from above in summer. With translucent dial plates (e.g. glass) the hour angles need only be marked on the sun-facing side, although the hour numberings (if used) need be made on both sides of the dial, owing to the differing hour schema on the sun-facing and sun-backing sides.

Another major advantage of this dial is that equation of time (EoT) and daylight saving time (DST) corrections can be made by simply rotating the dial plate by the appropriate angle each day. This is because the hour angles are equally spaced around the dial. For this reason, an equatorial dial is often a useful choice when the dial is for public display and it is desirable to have it show the true local time to reasonable accuracy. The EoT correction is made via the relation

Near the equinoxes in spring and autumn, the sun moves on a circle that is nearly the same as the equatorial plane; hence, no clear shadow is produced on the equatorial dial at those times of year, a drawback of the design.

A nodus is sometimes added to equatorial sundials, which allows the sundial to tell the time of year. On any given day, the shadow of the nodus moves on a circle on the equatorial plane, and the radius of the circle measures the declination of the sun. The ends of the gnomon bar may be used as the nodus, or some feature along its length. An ancient variant of the equatorial sundial has only a nodus (no style) and the concentric circular hour-lines are arranged to resemble a spider-web.[27]

Horizontal sundials

[edit]

In the horizontal sundial (also called a garden sundial), the plane that receives the shadow is aligned horizontally, rather than being perpendicular to the style as in the equatorial dial.[28] Hence, the line of shadow does not rotate uniformly on the dial face; rather, the hour lines are spaced according to the rule.[29]

Or in other terms:

where L is the sundial's geographical latitude (and the angle the gnomon makes with the dial plate), is the angle between a given hour-line and the noon hour-line (which always points towards true north) on the plane, and t is the number of hours before or after noon. For example, the angle of the 3 PM hour-line would equal the arctangent of sin L , since tan 45° = 1. When (at the North Pole), the horizontal sundial becomes an equatorial sundial; the style points straight up (vertically), and the horizontal plane is aligned with the equatorial plane; the hour-line formula becomes as for an equatorial dial. A horizontal sundial at the Earth's equator, where would require a (raised) horizontal style and would be an example of a polar sundial (see below).

The chief advantages of the horizontal sundial are that it is easy to read, and the sunlight lights the face throughout the year. All the hour-lines intersect at the point where the gnomon's style crosses the horizontal plane. Since the style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, the style points true north and its angle with the horizontal equals the sundial's geographical latitude L . A sundial designed for one latitude can be adjusted for use at another latitude by tilting its base upwards or downwards by an angle equal to the difference in latitude. For example, a sundial designed for a latitude of 40° can be used at a latitude of 45°, if the sundial plane is tilted upwards by 5°, thus aligning the style with the Earth's rotational axis. [citation needed]

Many ornamental sundials are designed to be used at 45 degrees north. Some mass-produced garden sundials fail to correctly calculate the hourlines and so can never be corrected. A local standard time zone is nominally 15 degrees wide, but may be modified to follow geographic or political boundaries. A sundial can be rotated around its style (which must remain pointed at the celestial pole) to adjust to the local time zone. In most cases, a rotation in the range of 7.5° east to 23° west suffices. This will introduce error in sundials that do not have equal hour angles. To correct for daylight saving time, a face needs two sets of numerals or a correction table. An informal standard is to have numerals in hot colors for summer, and in cool colors for winter.[citation needed] Since the hour angles are not evenly spaced, the equation of time corrections cannot be made via rotating the dial plate about the gnomon axis. These types of dials usually have an equation of time correction tabulation engraved on their pedestals or close by. Horizontal dials are commonly seen in gardens, churchyards and in public areas.

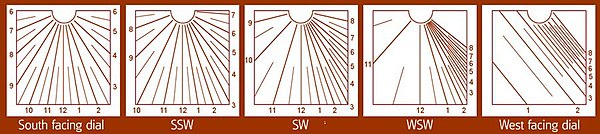

Vertical sundials

[edit]

In the common vertical dial, the shadow-receiving plane is aligned vertically; as usual, the gnomon's style is aligned with the Earth's axis of rotation.[30] As in the horizontal dial, the line of shadow does not move uniformly on the face; the sundial is not equiangular. If the face of the vertical dial points directly south, the angle of the hour-lines is instead described by the formula:[31]

where L is the sundial's geographical latitude, is the angle between a given hour-line and the noon hour-line (which always points due north) on the plane, and t is the number of hours before or after noon. For example, the angle of the 3 P.M. hour-line would equal the arctangent of cos L , since tan 45° = 1 . The shadow moves counter-clockwise on a south-facing vertical dial, whereas it runs clockwise on horizontal and equatorial north-facing dials.

Dials with faces perpendicular to the ground and which face directly south, north, east, or west are called vertical direct dials.[32] It is widely believed, and stated in respectable publications, that a vertical dial cannot receive more than twelve hours of sunlight a day, no matter how many hours of daylight there are.[33] However, there is an exception. Vertical sundials in the tropics which face the nearer pole (e.g. north facing in the zone between the Equator and the Tropic of Cancer) can actually receive sunlight for more than 12 hours from sunrise to sunset for a short period around the time of the summer solstice. For example, at latitude 20° North, on June 21, the sun shines on a north-facing vertical wall for 13 hours, 21 minutes.[34] Vertical sundials which do not face directly south (in the northern hemisphere) may receive significantly less than twelve hours of sunlight per day, depending on the direction they do face, and on the time of year. For example, a vertical dial that faces due East can tell time only in the morning hours; in the afternoon, the sun does not shine on its face. Vertical dials that face due East or West are polar dials, which will be described below. Vertical dials that face north are uncommon, because they tell time only during the spring and summer, and do not show the midday hours except in tropical latitudes (and even there, only around midsummer). For non-direct vertical dials – those that face in non-cardinal directions – the mathematics of arranging the style and the hour-lines becomes more complicated; it may be easier to mark the hour lines by observation, but the placement of the style, at least, must be calculated first; such dials are said to be declining dials.[35]

Vertical dials are commonly mounted on the walls of buildings, such as town-halls, cupolas and church-towers, where they are easy to see from far away. In some cases, vertical dials are placed on all four sides of a rectangular tower, providing the time throughout the day. The face may be painted on the wall, or displayed in inlaid stone; the gnomon is often a single metal bar, or a tripod of metal bars for rigidity. If the wall of the building faces toward the south, but does not face due south, the gnomon will not lie along the noon line, and the hour lines must be corrected. Since the gnomon's style must be parallel to the Earth's axis, it always "points" true north and its angle with the horizontal will equal the sundial's geographical latitude; on a direct south dial, its angle with the vertical face of the dial will equal the colatitude, or 90° minus the latitude.[36]

Polar dials

[edit]

In polar dials, the shadow-receiving plane is aligned parallel to the gnomon-style.[37] Thus, the shadow slides sideways over the surface, moving perpendicularly to itself as the Sun rotates about the style. As with the gnomon, the hour-lines are all aligned with the Earth's rotational axis. When the Sun's rays are nearly parallel to the plane, the shadow moves very quickly and the hour lines are spaced far apart. The direct East- and West-facing dials are examples of a polar dial. However, the face of a polar dial need not be vertical; it need only be parallel to the gnomon. Thus, a plane inclined at the angle of latitude (relative to horizontal) under the similarly inclined gnomon will be a polar dial. The perpendicular spacing X of the hour-lines in the plane is described by the formula

where H is the height of the style above the plane, and t is the time (in hours) before or after the center-time for the polar dial. The center time is the time when the style's shadow falls directly down on the plane; for an East-facing dial, the center time will be 6 A.M., for a West-facing dial, this will be 6 P.M., and for the inclined dial described above, it will be noon. When t approaches ±6 hours away from the center time, the spacing X diverges to +∞; this occurs when the Sun's rays become parallel to the plane.

Vertical declining dials

[edit]

A declining dial is any non-horizontal, planar dial that does not face in a cardinal direction, such as (true) north, south, east or west.[38] As usual, the gnomon's style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, but the hour-lines are not symmetrical about the noon hour-line. For a vertical dial, the angle between the noon hour-line and another hour-line is given by the formula below. Note that is defined positive in the clockwise sense w.r.t. the upper vertical hour angle; and that its conversion to the equivalent solar hour requires careful consideration of which quadrant of the sundial that it belongs in.[39]

where is the sundial's geographical latitude; t is the time before or after noon; is the angle of declination from true south, defined as positive when east of south; and is a switch integer for the dial orientation. A partly south-facing dial has an value of +1 ; those partly north-facing, a value of −1 . When such a dial faces south (), this formula reduces to the formula given above for vertical south-facing dials, i.e.

When a sundial is not aligned with a cardinal direction, the substyle of its gnomon is not aligned with the noon hour-line. The angle between the substyle and the noon hour-line is given by the formula[39]

If a vertical sundial faces trUe south Or north ( or respectively), the angle and the substyle is aligned with the noon hour-line.

The height of the gnomon, that is the angle the style makes to the plate, is given by :

Reclining dials

[edit]

The sundials described above have gnomons that are aligned with the Earth's rotational axis and cast their shadow onto a plane. If the plane is neither vertical nor horizontal nor equatorial, the sundial is said to be reclining or inclining.[41] Such a sundial might be located on a south-facing roof, for example. The hour-lines for such a sundial can be calculated by slightly correcting the horizontal formula above[42][43]

where is the desired angle of reclining relative to the local vertical, L is the sundial's geographical latitude, is the angle between a given hour-line and the noon hour-line (which always points due north) on the plane, and t is the number of hours before or after noon. For example, the angle of the 3pm hour-line would equal the arctangent of cos( L + R ) , since tan 45° = 1 . When R = 0° (in other words, a south-facing vertical dial), we obtain the vertical dial formula above.

Some authors use a more specific nomenclature to describe the orientation of the shadow-receiving plane. If the plane's face points downwards towards the ground, it is said to be proclining or inclining, whereas a dial is said to be reclining when the dial face is pointing away from the ground. Many authors also often refer to reclined, proclined and inclined sundials in general as inclined sundials. It is also common in the latter case to measure the angle of inclination relative to the horizontal plane on the sun side of the dial. In such texts, since the hour angle formula will often be seen written as :

The angle between the gnomon style and the dial plate, B, in this type of sundial is :

or :

Declining-reclining dials/ Declining-inclining dials

[edit]Some sundials both decline and recline, in that their shadow-receiving plane is not oriented with a cardinal direction (such as true north or true south) and is neither horizontal nor vertical nor equatorial. For example, such a sundial might be found on a roof that was not oriented in a cardinal direction.

The formulae describing the spacing of the hour-lines on such dials are rather more complicated than those for simpler dials.

There are various solution approaches, including some using the methods of rotation matrices, and some making a 3D model of the reclined-declined plane and its vertical declined counterpart plane, extracting the geometrical relationships between the hour angle components on both these planes and then reducing the trigonometric algebra.[44]

One system of formulas for Reclining-Declining sundials: (as stated by Fennewick)[45]

The angle between the noon hour-line and another hour-line is given by the formula below. Note that advances counterclockwise with respect to the zero hour angle for those dials that are partly south-facing and clockwise for those that are north-facing.

within the parameter ranges : and

Or, if preferring to use inclination angle, rather than the reclination, where :

within the parameter ranges : and

Here is the sundial's geographical latitude; is the orientation switch integer; t is the time in hours before or after noon; and and are the angles of reclination and declination, respectively. Note that is measured with reference to the vertical. It is positive when the dial leans back towards the horizon behind the dial and negative when the dial leans forward to the horizon on the Sun's side. Declination angle is defined as positive when moving east of true south. Dials facing fully or partly south have while those partly or fully north-facing have an Since the above expression gives the hour angle as an arctangent function, due consideration must be given to which quadrant of the sundial each hour belongs to before assigning the correct hour angle.

Unlike the simpler vertical declining sundial, this type of dial does not always show hour angles on its sunside face for all declinations between east and west. When a Northern Hemisphere partly south-facing dial reclines back (i.e. away from the Sun) from the vertical, the gnomon will become co-planar with the dial plate at declinations less than due east or due west. Likewise for Southern Hemisphere dials that are partly north-facing. Were these dials reclining forward, the range of declination would actually exceed due east and due west. In a similar way, Northern Hemisphere dials that are partly north-facing and Southern Hemisphere dials that are south-facing, and which lean forward toward their upward pointing gnomons, will have a similar restriction on the range of declination that is possible for a given reclination value. The critical declination is a geometrical constraint which depends on the value of both the dial's reclination and its latitude :

As with the vertical declined dial, the gnomon's substyle is not aligned with the noon hour-line. The general formula for the angle between the substyle and the noon-line is given by :

The angle between the style and the plate is given by :

Note that for i.e. when the gnomon is coplanar with the dial plate, we have :

i.e. when the critical declination value.[45]

Empirical method

[edit]Because of the complexity of the above calculations, using them for the practical purpose of designing a dial of this type is difficult and prone to error. It has been suggested that it is better to locate the hour lines empirically, marking the positions of the shadow of a style on a real sundial at hourly intervals as shown by a clock and adding/deducting that day's equation of time adjustment.[23] See Empirical hour-line marking, above.

Spherical sundials

[edit]

The surface receiving the shadow need not be a plane, but can have any shape, provided that the sundial maker is willing to mark the hour-lines. If the style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, a spherical shape is convenient since the hour-lines are equally spaced, as they are on the equatorial dial shown here; the sundial is equiangular. This is the principle behind the armillary sphere and the equatorial bow sundial.[46] However, some equiangular sundials – such as the Lambert dial described below – are based on other principles.

In the equatorial bow sundial, the gnomon is a bar, slot or stretched wire parallel to the celestial axis. The face is a semicircle, corresponding to the equator of the sphere, with markings on the inner surface. This pattern, built a couple of meters wide out of temperature-invariant steel invar, was used to keep the trains running on time in France before World War I.[47]

Among the most precise sundials ever made are two equatorial bows constructed of marble found in Yantra mandir.[48] This collection of sundials and other astronomical instruments was built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then-new capital of Jaipur, India between 1727 and 1733. The larger equatorial bow is called the Samrat Yantra (The Supreme Instrument); standing at 27 meters, its shadow moves visibly at 1 mm per second, or roughly a hand's breadth (6 cm) every minute.

Cylindrical, conical, and other non-planar sundials

[edit]

Other non-planar surfaces may be used to receive the shadow of the gnomon.

As an elegant alternative, the style (which could be created by a hole or slit in the circumference) may be located on the circumference of a cylinder or sphere, rather than at its central axis of symmetry.

In that case, the hour lines are again spaced equally, but at twice the usual angle, due to the geometrical inscribed angle theorem. This is the basis of some modern sundials, but it was also used in ancient times;[e]

In another variation of the polar-axis-aligned cylindrical, a cylindrical dial could be rendered as a helical ribbon-like surface, with a thin gnomon located either along its center or at its periphery.

Movable-gnomon sundials

[edit]Sundials can be designed with a gnomon that is placed in a different position each day throughout the year. In other words, the position of the gnomon relative to the centre of the hour lines varies. The gnomon need not be aligned with the celestial poles and may even be perfectly vertical (the analemmatic dial). These dials, when combined with fixed-gnomon sundials, allow the user to determine true north with no other aid; the two sundials are correctly aligned if and only if they both show the same time. [citation needed]

Universal equinoctial ring dial

[edit]

A universal equinoctial ring dial (sometimes called a ring dial for brevity, although the term is ambiguous), is a portable version of an armillary sundial,[50] or was inspired by the mariner's astrolabe.[51] It was likely invented by William Oughtred around 1600 and became common throughout Europe.[52]

In its simplest form, the style is a thin slit that allows the Sun's rays to fall on the hour-lines of an equatorial ring. As usual, the style is aligned with the Earth's axis; to do this, the user may orient the dial towards true north and suspend the ring dial vertically from the appropriate point on the meridian ring. Such dials may be made self-aligning with the addition of a more complicated central bar, instead of a simple slit-style. These bars are sometimes an addition to a set of Gemma's rings. This bar could pivot about its end points and held a perforated slider that was positioned to the month and day according to a scale scribed on the bar. The time was determined by rotating the bar towards the Sun so that the light shining through the hole fell on the equatorial ring. This forced the user to rotate the instrument, which had the effect of aligning the instrument's vertical ring with the meridian.

When not in use, the equatorial and meridian rings can be folded together into a small disk.

In 1610, Edward Wright created the sea ring, which mounted a universal ring dial over a magnetic compass. This permitted mariners to determine the time and magnetic variation in a single step.[53]

Analemmatic sundials

[edit]

Analemmatic sundials are a type of horizontal sundial that has a vertical gnomon and hour markers positioned in an elliptical pattern. There are no hour lines on the dial and the time of day is read on the ellipse. The gnomon is not fixed and must change position daily to accurately indicate time of day. Analemmatic sundials are sometimes designed with a human as the gnomon. Human gnomon analemmatic sundials are not practical at lower latitudes where a human shadow is quite short during the summer months. A 66 inches (170 cm) tall person casts a 4 inches (10 cm) shadow at 27° latitude on the summer solstice.[54]

Foster-Lambert dials

[edit]The Foster-Lambert dial is another movable-gnomon sundial.[55] In contrast to the elliptical analemmatic dial, the Lambert dial is circular with evenly spaced hour lines, making it an equiangular sundial, similar to the equatorial, spherical, cylindrical and conical dials described above. The gnomon of a Foster-Lambert dial is neither vertical nor aligned with the Earth's rotational axis; rather, it is tilted northwards by an angle α = 45° - (Φ/2), where Φ is the geographical latitude. Thus, a Foster-Lambert dial located at latitude 40° would have a gnomon tilted away from vertical by 25° in a northerly direction. To read the correct time, the gnomon must also be moved northwards by a distance

where R is the radius of the Foster-Lambert dial and δ again indicates the Sun's declination for that time of year.

Altitude-based sundials

[edit]

Altitude dials measure the height of the Sun in the sky, rather than directly measuring its hour-angle about the Earth's axis. They are not oriented towards true north, but rather towards the Sun and generally held vertically. The Sun's elevation is indicated by the position of a nodus, either the shadow-tip of a gnomon, or a spot of light.

In altitude dials, the time is read from where the nodus falls on a set of hour-curves that vary with the time of year. Many such altitude-dials' construction is calculation-intensive, as also the case with many azimuth dials. But the capuchin dials (described below) are constructed and used graphically.

Altitude dials' disadvantages:

Since the Sun's altitude is the same at times equally spaced about noon (e.g., 9am and 3pm), the user had to know whether it was morning or afternoon. At, say, 3:00 pm, that is not a problem. But when the dial indicates a time 15 minutes from noon, the user likely will not have a way of distinguishing 11:45 from 12:15.

Additionally, altitude dials are less accurate near noon, because the sun's altitude is not changing rapidly then.

Many of these dials are portable and simple to use. As is often the case with other sundials, many altitude dials are designed for only one latitude. But the capuchin dial (described below) has a version that's adjustable for latitude.[56]

Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 169 describe the Universal Capuchin sundial.

Human shadows

[edit]The length of a human shadow (or of any vertical object) can be used to measure the sun's elevation and, thence, the time.[57] The Venerable Bede gave a table for estimating the time from the length of one's shadow in feet, on the assumption that a monk's height is six times the length of his foot. Such shadow lengths will vary with the geographical latitude and with the time of year. For example, the shadow length at noon is short in summer months, and long in winter months.

Chaucer evokes this method a few times in his Canterbury Tales, as in his Parson's Tale.[f]

An equivalent type of sundial using a vertical rod of fixed length is known as a backstaff dial.

Shepherd's dial – timesticks

[edit]

A shepherd's dial – also known as a shepherd's column dial,[58][59] pillar dial, cylinder dial or chilindre – is a portable cylindrical sundial with a knife-like gnomon that juts out perpendicularly.[60] It is normally dangled from a rope or string so the cylinder is vertical. The gnomon can be twisted to be above a month or day indication on the face of the cylinder. This corrects the sundial for the equation of time. The entire sundial is then twisted on its string so that the gnomon aims toward the Sun, while the cylinder remains vertical. The tip of the shadow indicates the time on the cylinder. The hour curves inscribed on the cylinder permit one to read the time. Shepherd's dials are sometimes hollow, so that the gnomon can fold within when not in use.

The shepherd's dial is evoked in Henry VI, Part 3,[g] among other works of literature.

The cylindrical shepherd's dial can be unrolled into a flat plate. In one simple version,[62] the front and back of the plate each have three columns, corresponding to pairs of months with roughly the same solar declination (June:July, May:August, April:September, March:October, February:November, and January:December). The top of each column has a hole for inserting the shadow-casting gnomon, a peg. Often only two times are marked on the column below, one for noon and the other for mid-morning / mid-afternoon.

Timesticks, clock spear,[58] or shepherds' time stick,[58] are based on the same principles as dials.[58][59] The time stick is carved with eight vertical time scales for a different period of the year, each bearing a time scale calculated according to the relative amount of daylight during the different months of the year. Any reading depends not only on the time of day but also on the latitude and time of year.[59] A peg gnomon is inserted at the top in the appropriate hole or face for the season of the year, and turned to the Sun so that the shadow falls directly down the scale. Its end displays the time.[58]

Ring dials

[edit]In a ring dial (also known as an Aquitaine or a perforated ring dial), the ring is hung vertically and oriented sideways towards the sun.[63] A beam of light passes through a small hole in the ring and falls on hour-curves that are inscribed on the inside of the ring. To adjust for the equation of time, the hole is usually on a loose ring within the ring so that the hole can be adjusted to reflect the current month.

Card dials (Capuchin dials)

[edit]Card dials are another form of altitude dial.[64] A card is aligned edge-on with the sun and tilted so that a ray of light passes through an aperture onto a specified spot, thus determining the sun's altitude. A weighted string hangs vertically downwards from a hole in the card, and carries a bead or knot. The position of the bead on the hour-lines of the card gives the time. In more sophisticated versions such as the Capuchin dial, there is only one set of hour-lines, i.e., the hour lines do not vary with the seasons. Instead, the position of the hole from which the weighted string hangs is varied according to the season.

The Capuchin sundials are constructed and used graphically, as opposed the direct hour-angle measurements of horizontal or equatorial dials; or the calculated hour angle lines of some altitude and azimuth dials.

In addition to the ordinary Capuchin dial, there is a universal Capuchin dial, adjustable for latitude.

Navicula

[edit]

A navicula de Venetiis or "little ship of Venice" was an altitude dial used to tell time and which was shaped like a little ship. The cursor (with a plumb line attached) was slid up / down the mast to the correct latitude. The user then sighted the Sun through the pair of sighting holes at either end of the "ship's deck". The plumb line then marked what hour of the day it was.[citation needed]

Nodus-based sundials

[edit]

Another type of sundial follows the motion of a single point of light or shadow, which may be called the nodus. For example, the sundial may follow the sharp tip of a gnomon's shadow, e.g., the shadow-tip of a vertical obelisk (e.g., the Solarium Augusti) or the tip of the horizontal marker in a shepherd's dial. Alternatively, sunlight may be allowed to pass through a small hole or reflected from a small (e.g., coin-sized) circular mirror, forming a small spot of light whose position may be followed. In such cases, the rays of light trace out a cone over the course of a day; when the rays fall on a surface, the path followed is the intersection of the cone with that surface. Most commonly, the receiving surface is a geometrical plane, so that the path of the shadow-tip or light-spot (called declination line) traces out a conic section such as a hyperbola or an ellipse. The collection of hyperbolae was called a pelekonon (axe) by the Greeks, because it resembles a double-bladed ax, narrow in the center (near the noonline) and flaring out at the ends (early morning and late evening hours).

There is a simple verification of hyperbolic declination lines on a sundial: the distance from the origin to the equinox line should be equal to harmonic mean of distances from the origin to summer and winter solstice lines.[65]

Nodus-based sundials may use a small hole or mirror to isolate a single ray of light; the former are sometimes called aperture dials. The oldest example is perhaps the antiborean sundial (antiboreum), a spherical nodus-based sundial that faces true north; a ray of sunlight enters from the south through a small hole located at the sphere's pole and falls on the hour and date lines inscribed within the sphere, which resemble lines of longitude and latitude, respectively, on a globe.[66]

Reflection sundials

[edit]Isaac Newton developed a convenient and inexpensive sundial, in which a small mirror is placed on the sill of a south-facing window.[67] The mirror acts like a nodus, casting a single spot of light on the ceiling. Depending on the geographical latitude and time of year, the light-spot follows a conic section, such as the hyperbolae of the pelikonon. If the mirror is parallel to the Earth's equator, and the ceiling is horizontal, then the resulting angles are those of a conventional horizontal sundial. Using the ceiling as a sundial surface exploits unused space, and the dial may be large enough to be very accurate.

Multiple dials

[edit]Sundials are sometimes combined into multiple dials. If two or more dials that operate on different principles — such as an analemmatic dial and a horizontal or vertical dial — are combined, the resulting multiple dial becomes self-aligning, most of the time. Both dials need to output both time and declination. In other words, the direction of true north need not be determined; the dials are oriented correctly when they read the same time and declination. However, the most common forms combine dials are based on the same principle and the analemmatic does not normally output the declination of the sun, thus are not self-aligning.[68]

Diptych (tablet) sundial

[edit]

The diptych consisted of two small flat faces, joined by a hinge.[69] Diptychs usually folded into little flat boxes suitable for a pocket. The gnomon was a string between the two faces. When the string was tight, the two faces formed both a vertical and horizontal sundial. These were made of white ivory, inlaid with black lacquer markings. The gnomons were black braided silk, linen or hemp string. With a knot or bead on the string as a nodus, and the correct markings, a diptych (really any sundial large enough) can keep a calendar well-enough to plant crops. A common error describes the diptych dial as self-aligning. This is not correct for diptych dials consisting of a horizontal and vertical dial using a string gnomon between faces, no matter the orientation of the dial faces. Since the string gnomon is continuous, the shadows must meet at the hinge; hence, any orientation of the dial will show the same time on both dials.[70]

Multiface dials

[edit]A common type of multiple dial has sundials on every face of a Platonic solid (regular polyhedron), usually a cube.[71]

Extremely ornate sundials can be composed in this way, by applying a sundial to every surface of a solid object.

In some cases, the sundials are formed as hollows in a solid object, e.g., a cylindrical hollow aligned with the Earth's rotational axis (in which the edges play the role of styles) or a spherical hollow in the ancient tradition of the hemisphaerium or the antiboreum. (See the History section above.) In some cases, these multiface dials are small enough to sit on a desk, whereas in others, they are large stone monuments.

A Polyhedral's dial faces can be designed to give the time for different time-zones simultaneously. Examples include the Scottish sundial of the 17th and 18th centuries, which was often an extremely complex shape of polyhedral, and even convex faces.

Prismatic dials

[edit]Prismatic dials are a special case of polar dials, in which the sharp edges of a prism of a concave polygon serve as the styles and the sides of the prism receive the shadow.[72] Examples include a three-dimensional cross or star of David on gravestones.

Unusual sundials

[edit]Benoy dial

[edit]

The Benoy dial was invented by Walter Gordon Benoy of Collingham, Nottinghamshire, England. Whereas a gnomon casts a sheet of shadow, his invention creates an equivalent sheet of light by allowing the Sun's rays through a thin slit, reflecting them from a long, slim mirror (usually half-cylindrical), or focusing them through a cylindrical lens. Examples of Benoy dials can be found in the United Kingdom at:[73]

- Carnfunnock Country Park, County Antrim, Northern Ireland

- Upton Hall, British Horological Institute, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire

- Within the collections of St Edmundsbury Heritage Service, Bury St Edmunds[74]

- Longleat, Wiltshire

- Jodrell Bank Science Centre

- Birmingham Botanical Gardens

- Science Museum, London (inventory number 1975-318)

Bifilar sundial

[edit]

Invented by the German mathematician Hugo Michnik in 1922, the bifilar sundial has two non-intersecting threads parallel to the dial. Usually the second thread is orthogonal to the first.[75] The intersection of the two threads' shadows gives the local solar time.

Digital sundial

[edit]A digital sundial indicates the current time with numerals formed by the sunlight striking it. Sundials of this type are installed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich and in the Sundial Park in Genk (Belgium), and a small version is available commercially. There is a patent for this type of sundial.[76]

Globe dial

[edit]The globe dial is a sphere aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, and equipped with a spherical vane.[77] Similar to sundials with a fixed axial style, a globe dial determines the time from the Sun's azimuthal angle in its apparent rotation about the earth. This angle can be determined by rotating the vane to give the smallest shadow.

Noon marks

[edit]

The simplest sundials do not give the hours, but rather note the exact moment of 12:00 noon.[78] In centuries past, such dials were used to set mechanical clocks, which were sometimes so inaccurate as to lose or gain significant time in a single day. The simplest noon-marks have a shadow that passes a mark. Then, an almanac can translate from local solar time and date to civil time. The civil time is used to set the clock. Some noon-marks include a figure-eight that embodies the equation of time, so that no almanac is needed.

In some U.S. colonial-era houses, a noon-mark might be carved into a floor or windowsill.[79] Such marks indicate local noon, and provide a simple and accurate time reference for households to set their clocks. Some Asian countries had post offices set their clocks from a precision noon-mark. These in turn provided the times for the rest of the society. The typical noon-mark sundial was a lens set above an analemmatic plate. The plate has an engraved figure-eight shape, which corresponds to the equation of time (described above) versus the solar declination. When the edge of the Sun's image touches the part of the shape for the current month, this indicates that it is 12:00 noon.

Sundial cannon

[edit]A sundial cannon, sometimes called a 'meridian cannon', is a specialized sundial that is designed to create an 'audible noonmark', by automatically igniting a quantity of gunpowder at noon. These were novelties rather than precision sundials, sometimes installed in parks in Europe mainly in the late 18th or early 19th centuries. They typically consist of a horizontal sundial, which has in addition to a gnomon a suitably mounted lens, set to focus the rays of the sun at exactly noon on the firing pan of a miniature cannon loaded with gunpowder (but no ball). To function properly the position and angle of the lens must be adjusted seasonally.[citation needed]

Meridian lines

[edit]

A horizontal line aligned on a meridian with a gnomon facing the noon-sun is termed a meridian line and does not indicate the time, but instead the day of the year. Historically they were used to accurately determine the length of the solar year. Examples are the Bianchini meridian line in Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome, and the Cassini line in San Petronio Basilica at Bologna.[80]

Sundial mottoes

[edit]The association of sundials with time has inspired their designers over the centuries to display mottoes as part of the design. Often these cast the device in the role of memento mori, inviting the observer to reflect on the transience of the world and the inevitability of death. "Do not kill time, for it will surely kill thee." Other mottoes are more whimsical: "I count only the sunny hours," and "I am a sundial and I make a botch / of what is done far better by a watch." Collections of sundial mottoes have often been published through the centuries.[citation needed]

Use as a compass

[edit]If a horizontal-plate sundial is made for the latitude in which it is being used, and if it is mounted with its plate horizontal and its gnomon pointing to the celestial pole that is above the horizon, then it shows the correct time in apparent solar time. Conversely, if the directions of the cardinal points are initially unknown, but the sundial is aligned so it shows the correct apparent solar time as calculated from the reading of a clock, its gnomon shows the direction of True north or south, allowing the sundial to be used as a compass. The sundial can be placed on a horizontal surface, and rotated about a vertical axis until it shows the correct time. The gnomon will then be pointing to the north, in the northern hemisphere, or to the south in the southern hemisphere. This method is much more accurate than using a watch as a compass and can be used in places where the magnetic declination is large, making a magnetic compass unreliable. An alternative method uses two sundials of different designs. (See #Multiple dials, above.) The dials are attached to and aligned with each other, and are oriented so they show the same time. This allows the directions of the cardinal points and the apparent solar time to be determined simultaneously, without requiring a clock.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]

- Butterfield dial

- Equation clock

- Foucault pendulum

- Francesco Bianchini

- Horology

- Jantar Mantar

- Lahaina Noon

- Moondial

- Nocturnal—device for determining time by the stars at night.

- Qibla observation by shadows

- Schema for horizontal dials—pen and ruler constructions

- Schema for vertical declining dials—pen and ruler constructions

- Sciothericum telescopicum—a sundial invented in the 17th century that used a telescopic sight to determine the time of noon to within 15 seconds.

- Scottish sundial—the ancient renaissance sundials of Scotland.

- Shadows—free software for calculating and drawing sundials.

- Societat Catalana de Gnomònica

- Tide (time)—divisions of the day on early sundials.

- Water clock

- Wilanów Palace Sundial, created by Johannes Hevelius in about 1684.

- Zero shadow day

- Clock

Notes

[edit]- ^ In some technical writing, the word "gnomon" can also mean the perpendicular height of a nodus from the dial plate. The point where the style intersects the dial plate is called the gnomon root.

- ^ A clock showing sundial time always agrees with a sundial in the same locality.

- ^ Strictly, local mean time rather than standard time should be used. However, using standard time makes the sundial more useful, since it does not have to be corrected for time zone or longitude.

- ^ The equation of time is considered to be positive when "sundial time" is ahead of "clock time", negative otherwise. See the graph shown in the section #Equation of time correction, above. For example, if the equation of time is -5 minutes and the standard time is 9:40, the sundial time is 9:35.[24]

- ^ An example of such a half-cylindrical dial may be found at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.[49]

- ^

Chaucer: as in his Parson's Tale:

- It was four o'clock according to my guess,

- Since eleven feet, a little more or less,

- my shadow at the time did fall,

- Considering that I myself am six feet tall.

- ^

Henry VI, Part 3:

- O God! methinks it were a happy life

- To be no better than a homely swain;

- To sit upon a hill, as I do now,

- To carve out dials, quaintly, point by point,

- Thereby to see the minutes, how they run –

- How many makes the hour full complete,

- How many hours brings about the day,

- How many days will finish up the year,

- How many years a mortal man may live.[61]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Flagstaff Gardens, Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number H2041, Heritage Overlay HO793". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ Moss, Tony. "How do sundials work". British Sundial society. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

This ugly plastic 'non-dial' does nothing at all except display the 'designer's ignorance and persuade the general public that 'real' sundials don't work.

- ^ Beverly, Damon N. (2025-10-03). "Sundial [Ancient Inventions Series]". InventionsArchive.com. Retrieved 2025-10-18.

- ^ Trentin, Guglielmo; Repetto, Manuela (2013-02-08). Using Network and Mobile Technology to Bridge Formal and Informal Learning. Elsevier. ISBN 9781780633626. Archived from the original on 2023-04-21. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Depuydt, Leo (1 January 1998). "Gnomons at Meroë and Early Trigonometry". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 84: 171–180. doi:10.2307/3822211. JSTOR 3822211.

- ^ Slayman, Andrew (27 May 1998). "Neolithic Skywatchers". Archaeology Magazine Archive. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "BSS Glossary". British Sundial Society. Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 126–129; Waugh (1973), pp. 124–125

- ^ Sabanski, Carl. "The Sundial Primer". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Larson, Michelle B. "Making a sundial for the Southern hemisphere 1". Archived from the original on 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Larson, Michelle B. "Making a sundial for the Southern hemisphere 2". Archived from the original on 2021-03-17. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "The Sundial Register". British Sundial Society. Archived from the original on 2009-12-20. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Waugh (1973), pp. 48–50

- ^ Karney, Kevin. "Variation in the equation of time" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ^ "The Claremont, CA Bowstring Equatorial Photo Info". Archived from the original on 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Daniel, Christopher St. J.H. (2004). Sundials. Osprey Publishing. pp. 47 ff. ISBN 978-0-7478-0558-8. Retrieved 25 March 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Schmoyer, Richard L. (1983). "Designed for accuracy". Sunquest Sundial. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 34

- ^ Cousins, Frank W. (1973). Sundials: The art and science of gnomonics. New York, NY: Pica Press. pp. 189–195.

- ^ Stong, C.L. (1959). "The Amateur Scientist" (PDF). Scientific American. Vol. 200, no. 5. pp. 190–198. Bibcode:1959SciAm.200d.171S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0459-171. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2017-12-17.

- ^ Landes, David S. (2000). Revolution in Time : Clocks and the making of the modern world. London, UK: Viking. ISBN 0-670-88967-9. OCLC 43341298.

- ^ "The world's largest sundial, Jantar Mantar, Jaipur". Border Sundials. April 2016. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ a b Waugh (1973), pp. 106–107

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 205

- ^ Historic England. "Timepiece Sculpture (Grade II) (1391106)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 46–49; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 55–56, 96–98, 138–141; Waugh (1973), pp. 29–34

- ^ Schaldach, K. (2004). "The arachne of the Amphiareion and the origin of gnomonics in Greece". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 35 (4): 435–445. Bibcode:2004JHA....35..435S. doi:10.1177/002182860403500404. ISSN 0021-8286. S2CID 122673452.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 49–53; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 56–99, 101–143, 138–141; Waugh (1973), pp. 35–51

- ^ Rohr (1996), p. 52; Waugh (1973), p. 45

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 46–49; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 557–58, 102–107, 141–143; Waugh (1973), pp. 52–99

- ^ Rohr (1996), p. 65; Waugh (1973), p. 52

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 54–55; Waugh (1973), pp. 52–69

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 83

- ^ Morrissey, David. "Worldwide Sunrise and Sunset map". Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 55–69; Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 58; Waugh (1973), pp. 74–99

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 55

- ^ Rohr (1996), p. 72; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 58, 107–112; Waugh (1973), pp. 70–73

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 55–69; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 58–112, 101–117, 1458–146; Waugh (1973), pp. 74–99

- ^ a b Rohr (1996), p. 79

- ^ Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 138

- ^ Rohr (1965), pp. 70–81; Waugh (1973), pp. 100–107; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 59–60, 117–122, 144–145

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 77; Waugh (1973), pp. 101–103;

- ^ Sturmy, Samuel Capt. (1683). The Art of Dialling. London, UK.

- ^ Brandmaier 2005, pp. 16–23, Vol. 12, Issue 1; Snyder 2015, Vol. 22, Issue 1.

- ^ a b Fennerwick, Armyan. "the Netherlands, Revision of Chapter 5 of Sundials by René R.J. Rohr, New York 1996, declining inclined dials part D Declining and inclined dials by mathematics using a new figure". demon.nl. Netherlands. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 114, 1214–125; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 60, 126–129, 151–115; Waugh (1973), pp. 174–180

- ^ Rohr 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 118–119; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 215–216

- ^ Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 94

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 157

- ^ Swanick, Lois Ann (December 2005). An Analysis Of Navigational Instruments in the Age of Exploration: 15th Century to Mid-17th Century (MA thesis). Texas A&M University.

- ^ Turner (1980), p. 25

- ^ May, William Edward (1973). A History of Marine Navigation. Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, UK: G.T. Foulis & Co. ISBN 0-85429-143-1.

- ^ Budd, C.J.; Sangwin, C.J. Analemmatic sundials: How to build one and why they work (Report).

- ^ Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 190–192

- ^ Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 169

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 15; Waugh (1973), pp. 1–3

- ^ a b c d e Lippincott, Kristen; Eco, U.; Gombrich, E.H. (1999). The Story of Time. London, UK: Merrell Holberton / National Maritime Museum. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1-85894-072-9.

- ^ a b c "Telling the story of time measurement: The Beginnings". St. Edmundsbury Borough Council. Archived from the original on August 27, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ Rohr (1965), pp. 109–111; Waugh (1973), pp. 150–154; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 162–166

- ^ Shakespeare, W. Henry VI, Part 3. act 2, scene 5, lines 21–29.

- ^ Waugh (1973), pp. 166–167

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 111; Waugh (1973), pp. 158–160; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 159–162

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 110; Waugh (1973), pp. 161–165; Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 166–185

- ^ Belk, T. (September 2007). "Declination lines detailed" (PDF). BSS Bulletin. 19 (iii): 137–140. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-18.

- ^ Rohr (1996), p. 14

- ^ Waugh (1973), pp. 116–121

- ^ Bailey, Roger. "1 Conference Retrospective: Victoria BC 2015" (PDF). NASS Conferences. North American Sundial Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 112; Waugh (1973), pp. 154–155; Mayall & Mayall (1994), pp. 23–24

- ^ Waugh (1973), p. 155

- ^ Rohr (1965), p. 118; Waugh (1973), pp. 155–156; Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 59

- ^ Waugh (1973), pp. 181–190

- ^ List correct as of British Sundial Register 2000. "The Sundial Register". British Sundial Society. Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ St. Edmundsbury, Borough Council. "Telling the story of time measurement". Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ Michnik, H (1922). "Title: Theorie einer Bifilar-Sonnenuhr". Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 217 (5190): 81–90. Bibcode:1922AN....217...81M. doi:10.1002/asna.19222170602. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Digital sundial". Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- ^ Rohr (1996), pp. 114–115

- ^ Waugh (1973), pp. 18–28

- ^ Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 26

- ^ Manaugh, Geoff (15 November 2016). "Why Catholics built secret astronomical features into churches to help save souls". Atlas Obscura (atlasobscura.com). Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Portable Hemispherical Sundial". National Museum of Korea. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Brandmaier, H. (March 2005). "Sundial design using matrices". The Compendium. 12 (1). North American Sundial Society.

- Daniel, Christopher St. J.H. (2004). Sundials. Shire Album. Vol. 176 (2nd revised ed.). Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0747805588.

- Earle, A.M. (1971) [1902]. Sundials and Roses of Yesterday (reprint ed.). Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 0-8048-0968-2. LCCN 74142763 – via Internet Archive. Reprint of the 1902 book published by Macmillan (New York).

- Heilbron, J.L. (2001). The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as solar observatories. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00536-5.

- Herbert, A.P. (1967). Sundials Old and New. Methuen & Co.

- Kern, Ralf (2010). Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit vom 15. – 19. Jahrhundert [Scientific Instruments in their Era from the 15th–19th Centuries] (in German). Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. ISBN 978-3-86560-772-0.

- Mayall, R.N.; Mayall, M.W. (1994) [1938]. Sundials: Their construction and use (3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Sky Publishing. ISBN 0-933346-71-9.

- Michnik, Hugo (1922). "Theorie einer Bifilar-Sonnenuhr" [Theory of a bifilar sunial]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 217 (5190): 81–90. Bibcode:1922AN....217...81M. doi:10.1002/asna.19222170602.

- Rohr, R.R.J. (1996) [1965, 1970]. Sundials: History, theory, and practice. Translated by Godin, G. (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover. ISBN 0-486-29139-1 – via Internet Archive. Slightly amended reprint of the 1970 translation published by University of Toronto Press (Toronto). The original was

Rohr, R.R.J. (1965). Les Cadrans solaires [Sundials] (in French) (original ed.). Montrouge, FR: Gauthier-Villars. - Savoie, Denis (2009). Sundials: Design, construction, and use. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-09801-2.

- Sawyer, Frederick W. (1978). "Bifilar gnomonics". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 88 (4): 334–351. Bibcode:1978JBAA...88..334S.

- Snyder, Donald L. (March 2015). "Sundial design considerations" (PDF). The Compendium. 22 (1). St. Louis, MO: North American Sundial Society. ISSN 1074-3197. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Turner, Gerard L'E. (1980). Antique Scientific Instruments. Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1068-3.

- Walker, Jane; Brown, David, eds. (1991). Make a Sundial. The Education Group of the British Sundial Society. British Sundial Society. ISBN 0-9518404-0-1.

- Waugh, Albert E. (1973). Sundials: Their Theory and Construction. New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22947-5 – via Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]National organisations

[edit]- Asociación Amigos de los Relojes de Sol (AARS) – Spanish Sundial Society

- British Sundial Society (BSS) – British Sundial Society

- Commission des Cadrans Solaires de la Société Astronomique de France French Sundial Society

- Coordinamento Gnomonico Italiano Archived 2017-07-30 at the Wayback Machine (CGI) – Italian Sundial Society

- North American Sundial Society (NASS) – North American Sundial Society

- Societat Catalana de Gnomònica – Catalan Sundial Society

- De Zonnewijzerkring – Dutch Sundial Society (in English)

- Zonnewijzerkring Vlaanderen – Flemish Sundial Society

Historical