Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Axillary nerve.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Axillary nerve

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Axillary nerve

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

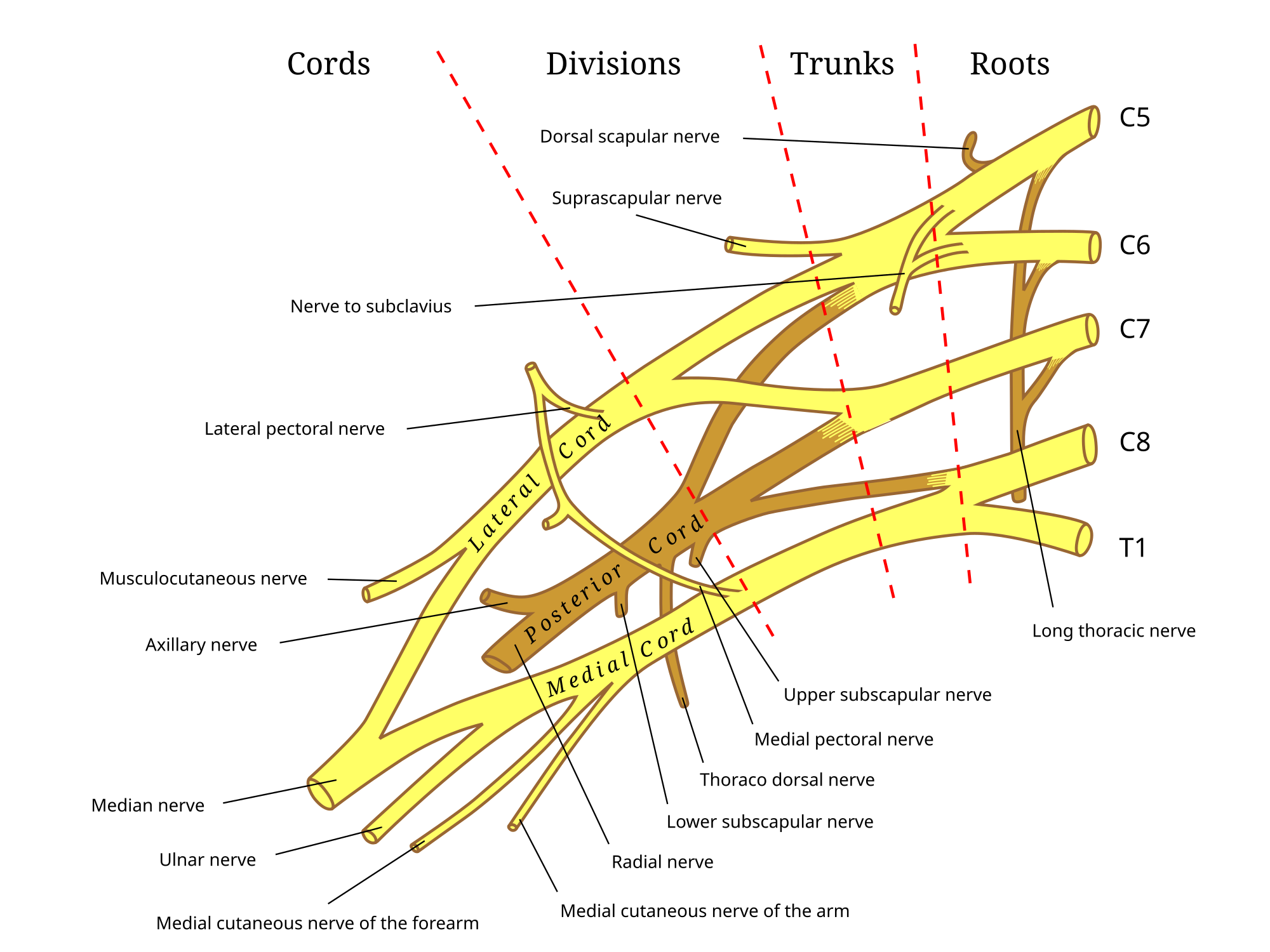

The axillary nerve is a peripheral nerve of the brachial plexus that originates from the posterior cord, primarily from the C5 and C6 spinal roots, and provides motor innervation to the deltoid and teres minor muscles while supplying sensory fibers to the skin over the lateral aspect of the shoulder.[1][2]

Emerging in the axilla posterior to the axillary artery and anterior to the subscapularis muscle, the axillary nerve travels posteriorly through the quadrangular space—bounded by the teres minor superiorly, teres major inferiorly, long head of the triceps medially, and surgical neck of the humerus laterally—before dividing into anterior and posterior branches near the surgical neck of the humerus, with the anterior branch coursing around 5-7 cm distal to the lateral acromion.[1][2] The anterior branch innervates the anterior and middle deltoid for shoulder flexion and abduction, while the posterior branch supplies the posterior deltoid and teres minor for extension and external rotation, respectively; additionally, an articular branch provides sensory innervation to the glenohumeral joint capsule.[1][2] Sensory function is mediated by the superior lateral brachial cutaneous nerve, a terminal branch that emerges from the posterior division and innervates the "regimental badge" area of skin over the deltoid region, enabling sensation in this superficial zone.[1][2]

Clinically, the axillary nerve is vulnerable to injury due to its close proximity to the humeral surgical neck and glenohumeral joint, with common mechanisms including anterior shoulder dislocations (reported in 9–55% of cases), proximal humerus fractures, or iatrogenic damage during surgical procedures like arthroscopy or proximal humerus nailing.[1][2][3] Such injuries often result in deltoid weakness leading to impaired shoulder abduction beyond 15 degrees, teres minor dysfunction manifesting as positive Hornblower's sign, and numbness in the lateral shoulder, though many cases recover spontaneously without intervention due to the nerve's regenerative potential.[1][2] In severe or persistent cases, associated with conditions like quadrangular space syndrome or Erb's palsy from upper trunk brachial plexus involvement, management may involve nerve conduction studies, physical therapy, or surgical exploration such as nerve grafting or transfer.[1][2]