Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Triceps.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Triceps

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Triceps

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

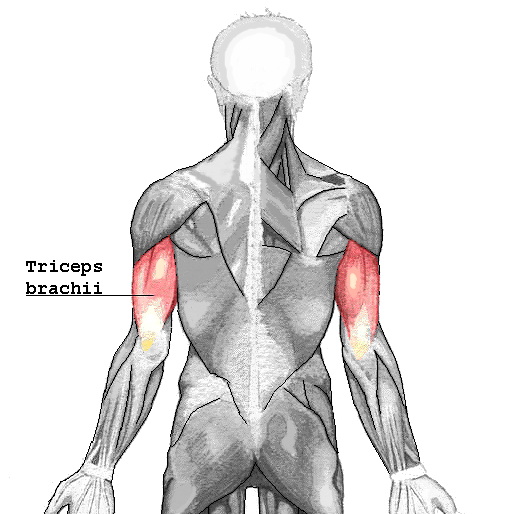

The triceps brachii is a large, fusiform muscle located in the posterior compartment of the upper arm, consisting of three distinct heads that primarily function to extend the elbow joint, enabling essential movements such as pushing and straightening the arm.[1] Composed of the long, lateral, and medial heads, it originates from the scapula and humerus before converging into a single tendon that inserts on the olecranon process of the ulna, making it the chief antagonist to the biceps brachii in forearm flexion.[2] This muscle plays a critical role in upper limb strength and stability, supporting activities like weight-bearing on the hands and wrists, as well as dynamic actions in sports and daily tasks.[3]

Structurally, the long head arises from the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, crossing both the shoulder and elbow joints, while the lateral head originates from the posterior surface of the humerus superior to the radial groove, and the medial head from the inferior aspect of the groove along the posterior humerus.[2] These heads unite distally to form the triceps tendon, which not only attaches to the ulna but also blends with the antebrachial fascia via expansions, contributing to overall arm stability.[4] The muscle is innervated by the radial nerve (roots C6–C8), which provides motor supply to all three heads, and receives its blood supply primarily from branches of the profunda brachii artery, ensuring robust perfusion during contraction.[2]

In terms of function, all heads of the triceps brachii contribute to elbow extension, with the long head additionally facilitating adduction and extension of the humerus at the shoulder joint, particularly in a third-class lever system where force is applied between the joint axis and load.[5] The lateral and medial heads are more active during elbow extension with the shoulder in neutral positions, whereas the long head predominates at higher shoulder elevations, optimizing force distribution across varying postures.[6] Clinically, the triceps is susceptible to tendon avulsions or strains from forceful extensions, such as in weightlifting or falls, highlighting its importance in rehabilitation and surgical interventions like triceps tendon repairs.[1]