Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chromosomal translocation

View on WikipediaThis article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (December 2011) |

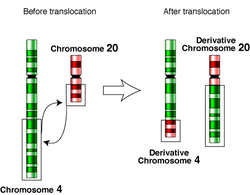

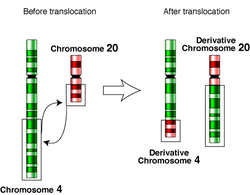

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes "balanced" and "unbalanced" translocation, with three main types: "reciprocal", "nonreciprocal" and "Robertsonian" translocation. Reciprocal translocation is a chromosome abnormality caused by exchange of parts between non-homologous chromosomes. Two detached fragments of two different chromosomes are switched. Robertsonian translocation occurs when two non-homologous chromosomes get attached, meaning that given two healthy pairs of chromosomes, one of each pair "sticks" and blends together homogeneously. Each type of chromosomal translocation can result in disorders for growth, function and the development of an individuals body, often resulting from a change in their genome.[1]

A gene fusion may be created when the translocation joins two otherwise-separated genes. It is detected on cytogenetics or a karyotype of affected cells. Translocations can be balanced (in an even exchange of material with no genetic information extra or missing, and ideally full functionality) or unbalanced (in which the exchange of chromosome material is unequal resulting in extra or missing genes).[1][2] Ultimately, these changes in chromosome structure can be due to deletions, duplications and inversions, and can result in 3 main kinds of structural changes.

History

[edit]Chromosomal translocations – in which a segment of one chromosome breaks off and attaches to another – were first observed in the early 20th century. In 1916, American zoologist William R. B. Robertson documented a chromosomal fusion in grasshoppers (now known as a Robertsonian translocation).[3] In 1938, Karl Sax demonstrated that X-ray irradiation could induce chromosomal translocations, observing radiation-induced fusions between different chromosomes in plant cells.[3] During the 1940s, Barbara McClintock's maize cytogenetics experiments revealed the breakage–fusion–bridge cycle of chromosomes, further illuminating mechanisms of chromosomal rearrangement.[4] A major breakthrough came in 1960 with the discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelogenous leukemia – the first consistent chromosomal abnormality linked to a human cancer.[citation needed] In 1973, Janet Rowley identified the Philadelphia chromosome as a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, definitively linking a specific chromosomal translocation to leukemia.[5]

In subsequent decades, technological advances greatly enhanced the detection and understanding of translocations. The introduction of chromosome banding techniques in the 1970s (e.g. Q-banding and G-banding) allowed more precise identification of individual chromosomes and their abnormalities in karyotypes.[6] The development of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in the early 1980s enabled researchers to label specific DNA sequences with fluorescent probes on chromosomes, dramatically improving the mapping of translocation breakpoints.[6] In the 21st century, high-throughput DNA sequencing (such as whole-genome sequencing) has made it possible to detect translocations at single-nucleotide resolution, leading to the discovery of numerous previously undetected translocations across different cancers and genetic disorders.[4]

Balanced reciprocal translocations

[edit]Reciprocal translocations involve an exchange of material between non-homologous chromosomes.[7] Such translocations are usually harmless, as they do not result in a gain or loss of genetic material, as is the case with nonreciprocal translocations. This type of translocation is often caused by erroneous repair of double stranded breaks or non-homologous crossing over in meiosis.[7]

A common balanced reciprocal translocation is the exchange of material between chromosome 11 and 22. Individuals with this chromosomal abnormality do not experience any phenotypic effects but are subject to issues with fertility since carriers of balanced reciprocal translocations may create gametes with unbalanced reciprocal or nonreciprocal chromosome translocations.[8] The combination of the carrier's gamete with the wild type gamete from the other parent may result in duplication or deletion of genetic material based on segregation of chromosomes during meiosis.[8] This can lead to infertility, miscarriages or children with abnormalities. Genetic counselling and genetic testing are often offered to families that may carry a translocation. A common example of a birth defect that may result from the carrier of the translocation mentioned above is Emanuel Syndrome.[9]

Unbalanced reciprocal translocations

Unbalanced reciprocal translocations are similar to balanced reciprocal translocations in that they involve the exchange of genetic information between two non-homologous chromosomes.[10] However, with unbalanced reciprocal translocations, the process results in the duplication or deletion of some genetic material as well. Since there is a genetic imbalance, individuals with an unbalanced reciprocal translocation will often exhibit phenotype reflective of the abnormal gene expression.[10]

Most unbalanced reciprocal translocations are a result of inheritance from a parent with a balanced translocation.[11] As mentioned previously, parents with balanced translocations are likely to give birth to children with unbalanced translocations. Although less common, unbalanced translocations may form due to errors during gametogenesis or errors in repair of double stranded DNA breaks.[11]

Nonreciprocal translocation

[edit]Nonreciprocal translocation is a chromosomal abnormality that involves the one-way transfer of genes from one chromosome to another non-homologous chromosome. This transfer will always be unbalanced resulting in genetic imbalance. This excess or deletion of genetic material compared to a normal genome is likely to result in disease.

Nonreciprocal translocations can occur as a result of three main processes. Errors during DNA replication, unequal crossing over in meiosis or mitosis and/or exogenous factors causing double stranded DNA damage.[12] When a chromosome experiences a double strand break at one or more locations it may rejoin to a non-homologous chromosome.[12] In the case of nonreciprocal translocations, the acceptor chromosome gains material but the donor chromosome does not accept material in exchange. This unequal transfer causes loss of genetic material which may have varying degrees of impact.

A number of factors affect the impact of the translocation. The segment of the chromosome affected by the double strand break may be in a coding or noncoding region.[13] Therefore, the rearrangement may result in a number of affects to the gene. Essential genes may be silenced or oncogenes may be activated.[13] The chromosome on which the translocation occurs may also affect the result due to certain chromosomes containing more essential genes. Which cell type the translocation occurs in may also have an affect. Somatic cells are more likely to result in cancer, where germ line cells are more likely to result in birth defects including miscarriages and still births.[14]

One specific example of an unbalanced nonreciprocal translocation is Emanuel Syndrome. At the chromosomal level, a fragment from chromosome 11 is non-reciprocally translocated to chromosome 22 creating genetic imbalances.[9] Phenotypically, Emanuel Syndrome presents as neurological and physical developmental disorders, microcephaly, and congenital defects.[9]

Robertsonian translocations

[edit]Robertsonian translocation is a type of translocation caused by breaks at or near the centromeres of two acrocentric chromosomes. The reciprocal exchange of parts gives rise to one large metacentric chromosome and one extremely small chromosome that may be lost from the organism with little effect because it contains few genes. The resulting karyotype in humans leaves only 45 chromosomes, since two chromosomes have fused together.[15] This has no direct effect on the phenotype, since the only genes on the short arms of acrocentrics are common to all of them and are present in variable copy number (nucleolar organiser genes).

Robertsonian translocations have been seen involving all combinations of acrocentric chromosomes. The most common translocation in humans involves chromosomes 13 and 14 and is seen in about 0.97 / 1000 newborns.[16] Carriers of Robertsonian translocations are not associated with any phenotypic abnormalities, but there is a risk of unbalanced gametes that lead to miscarriages or abnormal offspring. For example, carriers of Robertsonian translocations involving chromosome 21 have a higher risk of having a child with Down syndrome. This is known as a 'translocation Downs'. This is due to a mis-segregation (nondisjunction) during gametogenesis. The mother has a higher (10%) risk of transmission than the father (1%). Robertsonian translocations involving chromosome 14 also carry a slight risk of uniparental disomy 14 due to trisomy rescue.

Chromosomal structural changes

[edit]Changes in chromosome structure can be due to deletions, duplications and inversions, ultimately resulting in 3 main kinds of structural changes.

Isochromosomes result when a chromosome has two identical arms, such as two P or two Q arms, instead of the expected Q and P pairing. These isochromosomal structural changes can result in a loss of information, as well as a change in expression within the body due to the duplication of one set of chromosomal arms.[17]

Dicentric chromosomes are chromosomes with two centromeres, resulting in an instability within the chromosome and a loss of genetic information due to the fusion of two chromosome pieces with a centromere.[17] This results in a singular chromosome having two centromeres, due to the fusion of two chromosomal pieces with one centromere each, therefore resulting in the fusion of two centromeres.

Ring chromosomes are chromosomes that form when the ends of the previous chromosomes break off to form a circular structure.[18] This results in a loss of genetic material as well as the potential loss of the chromosomal centromere.[17]

DNA double-strand breaks with translocations

[edit]The initiating event in the formation of a translocation is generally a double-strand break in chromosomal DNA.[19] Double stranded breaks in chromosomal DNA can occur for many reasons, however a major role in generating these translocations is the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway.[19][20] When this pathway functions appropriately, it restores a DNA double-strand break by reconnecting the originally broken ends using their sticky or blunt ends that have been generated by the enzyme and protein machinery. However, when the NHEJ pathway acts inappropriately, it may join ends incorrectly, therefore resulting in genomic rearrangements including translocations. These incorrect combinations are the result of sequences in close proximity that have similar homology, but not perfect homology, yet it is recognized by the repair machinery as perfect. This then leads the machinery to begin repairing using NHEJ with the wrong sequences, resulting in deletions and insertions of specific nucleotides, or the joining of incorrect end sequences.[21] Ultimately, these issues arise due to a misread of the homologous sequences by the protein or enzyme machinery, and leads to the mis-incorporation of incorrect sequences into the genome. when the genomes of slightly homologous sequences are in too close of proximity, resulting in the machinery becoming confused or mistaking the wrong sequence for the correct one.[22]

Another influence in generating DNA double stranded break translocations is through the creation of AID translocations. These sequences are the result of a deamination procedure of a cytosine nucleotide into a uracil nucleotide. This change ultimately results in a mismatch between the complementary sequence and its target sequence, therefore resulting in a translocation. When further processed by specific endonucleases, this uracil leads to a mutation or a double stranded break.[23] Once again, these double stranded break and the mismatch that occurred lead to a translocation of the genomic sequence, which in turn have effect on the chromosome the DNA is present on.

Finally, new information is surfacing regarding the influence of exogenous rare-cutting endonucleases on DNA double stranded breaks and their resulting chromosomal translocations.[24][25] Specifically, during DNA double strand break repair, reflections of misjoining of exchanged sequence ends have be noted, primarily due to the mishomology present by the NHEJ pathway. However, at these specific break points, additional nucleic acid and DNA sequence loss has been found, therefore leading to the conclusion that additional exogenous rare-cutting endonucleases are present at various locations on these strands. Each deletion results in a varying size, location or cut version, ultimately suggesting DNA degradation by endonucleases prior to NHEJ joining.[25] Additional influences on DNA degradation similar to that of exogenous rare-cutting endonucleases has also been noted as a result of cytotoxic chemotherapy,[26] ionizing radiation, although further research is needed in order to provide more conclusive and viable answers.[27]

Overall, through various mechanisms, DNA double-strand breaks and sources of DNA double-strand break repair are able to generate both reciprocal and non reciprocal chromosomal translocations.[25] Such DNA breaks and repair mechanisms are also able to generate gross chromosomal mutations, inclusive of not only translocations, but also inversions, amplifications and simple deletions, all resulting in null or dangerous transformations.[27]

Role in disease

[edit]Chromosomal translocations can cause a diverse array of diseases, mutations or other heritable changes within an individuals genomes. Often, these mutations are caused by the loss of genetic information resulting from a structural change in the chromosome. There are three main forms of structural changes, and each of these has a role within the creation of disease. Whether it be from the structural changes themselves, or directly from the loss of genetic information, many varying diseases or mutations can be acquired due to chromosomal translocations.

A prevalent and dangerous disease resulting from chromosomal translocations is Cancer.[28] There are several forms of cancer that are caused by acquired translocations, many of them falling within the classifications of leukemia,[29] acute myelogenous leukemia,[30] and chronic myelogenous leukemia,[31] with additional translation classifications being detected within solid malignancies such as Ewing's sarcoma.[32] Regardless of the cancer classification, the most common process for generation of these cancers is through the disruption or misregulation of normal gene function. This results in the molecular rearrangement of the genes necessary for proper gene regulation, therefore resulting in cancer formation.[33] An alternative way that such cancers can be formed is through the fusion of coding sequences. This fusion results from the translation forcing the generation of a ring or iso chromosome, or from DNA end joining due to a close proximity between homologues genes, therefore creating a potent, fused oncogene.[34][35]

Infertility is also a prevalent and common form of disease that is generated by chromosomal translocations, and often can be asymptomatic or symptomatic within fetuses.[36] Commonly influenced by one of the parents being a carrier for a balanced translocation yet being asymptomatic, the offspring often acquire additional mutations prior to birth resulting in the effect and symptomatic response due to the presence of the translocation within their genome. Ultimately, this symptomatic response is discovered when homology between two individuals genomes results in the loss of genetic information from the asymptomatic chromosomal translocation becoming problematic.[33][37]

In addition, the inheritance of Down syndrome[38] can be caused by chromosomal translocations. In a minority (approximately 3 - 4%) of Down syndrome syndrome cases, the cause for this mutation is that of a Robertsonian translocation of chromosomes. This results from the Robertsonian translocation of the chromosome 21 long arm, onto the long arm of chromosome 14.[39] These translocations can also occur onto other chromsomes, such as chromosome 13, 15, or 22 resulting in these chromosomes also being referred to as Robertsonian chromosomes. Regardless of where, the result is a loss of information on chromosome 21 genes, and an addition of genetic information on the altering chromosome.[39]

Finally, chromosomal translocations between the sex chromosomes can also result in a number of genetic conditions, such as XX male syndrome,[40] which is caused by a translocation of the SRY gene from the Y to the X chromosome.[41] Alternatively, additional genetic diseases can also be a result of chromosomal translocations, such as Emmanuel syndrome,[42] Klinfelter syndrome[43] and Turner syndrome.[44]

By chromosome

[edit]

ALL – Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

AML – Acute myeloid leukemia

CML – Chronic myelogenous leukemia

DFSP – Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Denotation

[edit]The International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) is used to denote a translocation between chromosomes.[46] The designation "t(A;B)(p1;q2)" is used to denote a translocation between chromosome A and chromosome B. The information in the second set of parentheses, when given, gives the precise location within the chromosome for chromosomes A and B respectively—with p indicating the short arm of the chromosome, q indicating the long arm, and the numbers after p or q refers to regions, bands and sub-bands seen when staining the chromosome with a staining dye.[47] See also the definition of a genetic locus.

The translocation is the mechanism that can cause a gene to move from one linkage group to another.

Examples of translocations on human chromosomes

[edit]| Translocation | Associated diseases | Fused genes/proteins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | ||

| t(8;14)(q24;q32) | Burkitt's lymphoma

– occurs in ~70% of cases, places MYC under IGH enhancer control [48] |

c-myc on chromosome 8, gives the fusion protein lymphocyte-proliferative ability |

IGH@ (immunoglobulin heavy locus) on chromosome 14, induces massive transcription of fusion protein |

| t(11;14)(q13;q32) | Mantle cell lymphoma[49] – present in most cases [50] | cyclin D1[49] on chromosome 11, gives fusion protein cell-proliferative ability |

IGH@[49] (immunoglobulin heavy locus) on chromosome 14, induces massive transcription of fusion protein |

| t(14;18)(q32;q21) | Follicular lymphoma (~90% of cases)[51] | IGH@[49] (immunoglobulin heavy locus) on chromosome 14, induces massive transcription of fusion protein |

Bcl-2 on chromosome 18, gives fusion protein anti-apoptotic abilities |

| t(10;(various))(q11;(various)) | Papillary thyroid cancer[52] | RET proto-oncogene[52] on chromosome 10 | PTC (Papillary Thyroid Cancer) – Placeholder for any of several other genes/proteins[52] |

| t(2;3)(q13;p25) | Follicular thyroid cancer[52] | PAX8 – paired box gene 8[52] on chromosome 2 | PPARγ1[52] (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ 1) on chromosome 3 |

| t(8;21)(q22;q22)[51] | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation | ETO on chromosome 8 | AML1 on chromosome 21 found in ~7% of new cases of AML, carries a favorable prognosis and predicts good response to cytosine arabinoside therapy[51] |

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) Philadelphia chromosome | Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | Abl1 gene on chromosome 9[53] | BCR ("breakpoint cluster region" on chromosome 22[53] |

| t(15;17)(q22;q21)[51] | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | PML protein on chromosome 15 | RAR-α on chromosome 17 persistent laboratory detection of the PML-RARA transcript is strong predictor of relapse[51] |

| t(12;15)(p13;q25) | Acute myeloid leukemia, congenital fibrosarcoma, secretory breast carcinoma, mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, cellular variant of mesoblastic nephroma | TEL on chromosome 12 | TrkC receptor on chromosome 15 |

| t(9;12)(p24;p13) | CML, ALL | JAK on chromosome 9 | TEL on chromosome 12 |

| t(12;16)(q13;p11) | Myxoid liposarcoma | DDIT3 (formerly CHOP) on chromosome 12 | FUS gene on chromosome 16 |

| t(12;21)(p12;q22) | ALL | TEL on chromosome 12 | AML1 on chromosome 21 |

| t(11;18)(q21;q21) | MALT lymphoma[54] | BIRC3 (API-2) | MLT[54] |

| t(1;11)(q42.1;q14.3) | Schizophrenia[45] (familial translocation disrupting DISC1)[55] | DISC1 (1q42)[55] | DISC1FP1 (11q14)[55] |

| t(2;5)(p23;q35) | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | ALK | NPM1 |

| t(11;22)(q24;q11.2-12) | Ewing's sarcoma | FLI1 | EWS |

| t(17;22) | DFSP | COL1A1/Collagen I on chromosome 17 | Platelet derived growth factor B on chromosome 22 |

| t(1;12)(q21;p13) | Acute myelogenous leukemia (rare subtype)[56] | ETV6 (TEL, 12p13)[56] | ARNT (1q21)[56] |

| t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) | Synovial sarcoma - 90% of cases[57] | SS18 (18q11)[57] | SSX1/SSX2 (Xp11)[57] |

| t(1;19)(q10;p10) | Oligodendroglioma and oligoastrocytoma | Associated with the 1p/19q co-deletion in oligodendroglioma and oligoastrocytoma, rather than a specific gene fusion[58][59] | |

| t(17;19)(q22;p13) | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia very rare subtype, <1% of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. (associated with poor prognosis)[60] | TCF3 (E2A, 19p13)[60] | HLF (17q22)[60] |

| t(7,16) (q32-34;p11) or t(11,16) (p11;p11) | Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma – most cases [61] | FUS (16p11)[61] | CREB3L1 (11p11)[61] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "EuroGentest: Chromosome Translocations". www.eurogentest.org. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ "Can changes in the structure of chromosomes affect health and development?". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b HROMAS, ROBERT; WILLIAMSON, ELIZABETH; LEE, SUK-HEE; NICKOLOFF, JAC (2016). "Preventing the Chromosomal Translocations That Cause Cancer". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 127: 176–195. PMC 5216476. PMID 28066052.

- ^ a b Oviedo de Valeria, Jenny (August 2, 1994). "Problemas multiplicativos tip transformacion lineal: tareas de compra y venta". Educación matemática. 6 (2): 73–86. doi:10.24844/em0602.06. ISSN 2448-8089.

- ^ Rowley, Janet D. (June 1973). "A New Consistent Chromosomal Abnormality in Chronic Myelogenous Leukaemia identified by Quinacrine Fluorescence and Giemsa Staining". Nature. 243 (5405): 290–293. Bibcode:1973Natur.243..290R. doi:10.1038/243290a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Case, Sean (July 27, 2020). "History and Evolution of Cytogenetics". Behind the Bench. Retrieved March 13, 2025.

- ^ a b Therman, Eeva; Susman, Millard (1993), Therman, Eeva; Susman, Millard (eds.), "Reciprocal Translocations", Human Chromosomes: Structure, Behavior, and Effects, New York, NY: Springer US, pp. 273–287, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0529-3_26, ISBN 978-1-4684-0529-3, retrieved April 2, 2025

- ^ a b Wilch, Ellen S.; Morton, Cynthia C. (2018), Zhang, Yu (ed.), "Historical and Clinical Perspectives on Chromosomal Translocations", Chromosome Translocation, vol. 1044, Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–14, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0593-1_1, ISBN 978-981-13-0593-1, PMID 29956287, retrieved April 2, 2025

- ^ a b c PMC, Europe. "Europe PMC". europepmc.org. Retrieved April 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Parslow, Malcolm; Chambers, Diana; Aftimos, Salim (1981). "An inherited reciprocal translocation—balanced or unbalanced?". Pathology. 13 (1): 174. doi:10.1016/S0031-3025(16)38470-7.

- ^ a b Chen, Chih-Ping; Wu, Pei-Chen; Lin, Chen-Ju; Chern, Schu-Rern; Tsai, Fuu-Jen; Lee, Chen-Chi; Town, Dai-Dyi; Chen, Wen-Lin; Chen, Li-Feng; Lee, Meng-Shan; Pan, Chen-Wen; Wang, Wayseen (March 2011). "Unbalanced reciprocal translocations at amniocentesis". Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 50 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2011.02.001. PMID 21482375.

- ^ a b Ali, Hanif; Daser, Angelika; Dear, Paul; Wood, Henry; Rabbitts, Pamela; Rabbitts, Terence (2013). "Nonreciprocal chromosomal translocations in renal cancer involve multiple DSBs and NHEJ associated with breakpoint inversion but not necessarily with transcription". Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 52 (4): 402–409. doi:10.1002/gcc.22038. ISSN 1098-2264. PMID 23341332.

- ^ a b Nikitin, Dmitri; Tosato, Valentina; Zavec, Apolonija Bedina; Bruschi, Carlo V. (July 15, 2008). "Cellular and molecular effects of nonreciprocal chromosome translocations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (28): 9703–9708. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9703N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800464105. PMC 2474487. PMID 18599460.

- ^ Nambiar, Mridula; Kari, Vijayalakshmi; Raghavan, Sathees C. (December 2008). "Chromosomal translocations in cancer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1786 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.07.005. PMID 18718509.

- ^ Hartwell, Leland H. (2011). Genetics: From Genes to Genomes. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-07-352526-6.

- ^ E. Anton; J. Blanco; J. Egozcue; F. Vidal (April 29, 2004). "Sperm FISH studies in seven male carriers of Robertsonian translocation t(13;14)(q10;q10)". Human Reproduction. 19 (6): 1345–1351. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh232. ISSN 1460-2350. PMID 15117905.

- ^ a b c Mehta, Parang. "What Are Translocations?". WebMD. Retrieved April 2, 2025.

- ^ Yip, Moh-Ying (April 2015). "Autosomal ring chromosomes in human genetic disorders". Translational Pediatrics. 4 (2): 164–174. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.03.04. PMC 4729093. PMID 26835370.

- ^ a b Agarwal, S.; Tafel, A. A.; Kanaar, R. (2006). "DNA double-strand break repair and chromosome translocations". DNA Repair. 5 (9–10): 1075–1081. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.029. PMID 16798112.

- ^ Bohlander, Stefan K.; Kakadia, Purvi M. (2015). "DNA Repair and Chromosomal Translocations". Chromosomal Instability in Cancer Cells. Recent Results in Cancer Research. Vol. 200. pp. 1–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20291-4_1. ISBN 978-3-319-20290-7. PMID 26376870.

- ^ Steyer, Benjamin; Cory, Evan; Saha, Krishanu (August 2018). "Developing precision medicine using scarless genome editing of human pluripotent stem cells". Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. 28: 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2018.02.001. PMC 6136251. PMID 30205878.

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)—an error prone DNA repair process where double strand breaks are directly ligated, commonly resulting in insertion or deletion mutations.

- ^ Rocha, P. P.; Chaumeil, J.; Skok, J. A. (2013). "Molecular biology. Finding the right partner in a 3D genome". Science. 342 (6164): 1333–1334. doi:10.1126/science.1246106. PMC 3961821. PMID 24337287.

- ^ Nambiar, Mridula; Raghavan, Sathees C. (August 2011). "How does DNA break during chromosomal translocations?". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (14): 5813–5825. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr223. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 3152359. PMID 21498543.

- ^ Jasin, Maria (June 1996). "Genetic manipulation of genomes with rare-cutting endonucleases". Trends in Genetics. 12 (6): 224–228. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(96)10019-6. PMID 8928227.

- ^ a b c Povirk, Lawrence F. (September 2006). "Biochemical mechanisms of chromosomal translocations resulting from DNA double-strand breaks". DNA Repair. 5 (9–10): 1199–1212. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.016. PMID 16822725.

- ^ "Chemotherapy - What it is, types, treatment and side effects". www.macmillan.org.uk. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Qiu, Zhijun; Zhang, Zhenhua; Roschke, Anna; Varga, Tamas; Aplan, Peter D. (February 22, 2017). "Generation of Gross Chromosomal Rearrangements by a Single Engineered DNA Double Strand Break". Scientific Reports. 7 (1) 43156. Bibcode:2017NatSR...743156Q. doi:10.1038/srep43156. hdl:2437/288170. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5320478. PMID 28225067.

- ^ "Cancer - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Leukemia—Patient Version - NCI". www.cancer.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment - NCI". www.cancer.gov. April 4, 2025. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Chronic myelogenous leukemia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Ewing sarcoma - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ a b "Human Chromosome Translocations and Cancer | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved April 2, 2025.

- ^ Streb, Patrick; Kowarz, Eric; Benz, Tamara; Reis, Jennifer; Marschalek, Rolf (June 2023). "How chromosomal translocations arise to cause cancer: Gene proximity, trans-splicing, and DNA end joining". iScience. 26 (6) 106900. Bibcode:2023iSci...26j6900S. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.106900. PMC 10291325. PMID 37378346.

- ^ Aplan, Peter D. (January 2006). "Causes of oncogenic chromosomal translocation". Trends in Genetics. 22 (1): 46–55. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.002. ISSN 0168-9525. PMC 1762911. PMID 16257470.

- ^ "Infertility". www.who.int. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ Zhang, Hong-Guo; Wang, Rui-Xue; Pan, Yuan; Zhang, Han; Li, Lei-Lei; Zhu, Hai-Bo; Liu, Rui-Zhi (January 25, 2018). "A report of nine cases and review of the literature of infertile men carrying balanced translocations involving chromosome 5". Molecular Cytogenetics. 11 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s13039-018-0360-x. ISSN 1755-8166. PMC 5785882. PMID 29416565.

- ^ CDC (December 26, 2024). "Down Syndrome". Birth Defects. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of. "Translocation Down Syndrome | Children's Hospital of Philadelphia". www.chop.edu. Retrieved April 2, 2025.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). "Chromosomal Sex Determination in Mammals". Developmental Biology. 6th edition. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ "SRY gene" (PDF). medlineplus.gov.

- ^ "Emanuel syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics".

- ^ Gaviria, Anibal; Cadena-Ullauri, Santiago; Cevallos, Francisco; Guevara-Ramirez, Patricia; Ruiz-Pozo, Viviana; Tamayo-Trujillo, Rafael; Paz-Cruz, Elius; Zambrano, Ana Karina (September 5, 2022). "Clinical, cytogenetic, and genomic analyses of an Ecuadorian subject with Klinefelter syndrome, recessive hemophilia A, and 1;19 chromosomal translocation: a case report". Molecular Cytogenetics. 15 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/s13039-022-00618-w. PMC 9446752. PMID 36064723.

- ^ "A genetic disorder that affects females-Turner syndrome - Symptoms & causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ a b Semple CA, Devon RS, Le Hellard S, Porteous DJ (April 2001). "Identification of genes from a schizophrenia-linked translocation breakpoint region". Genomics. 73 (1): 123–6. doi:10.1006/geno.2001.6516. PMID 11352574.

- ^ Schaffer, Lisa. (2005) International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature S. Karger AG ISBN 978-3-8055-8019-9

- ^ "Characteristics of chromosome groups: Karyotyping". rerf.jp. Radiation Effects Research Foundation. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Zheng, Jie (November 1, 2013). "Oncogenic chromosomal translocations and human cancer (Review)". Oncology Reports. 30 (5): 2011–2019. doi:10.3892/or.2013.2677. ISSN 1021-335X. PMID 23970180.

- ^ a b c d Li JY, Gaillard F, Moreau A, et al. (May 1999). "Detection of translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) in mantle cell lymphoma by fluorescence in situ hybridization". Am. J. Pathol. 154 (5): 1449–52. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65399-0. PMC 1866594. PMID 10329598.

- ^ Zheng, Jie (November 1, 2013). "Oncogenic chromosomal translocations and human cancer (Review)". Oncology Reports. 30 (5): 2011–2019. doi:10.3892/or.2013.2677. ISSN 1021-335X. PMID 23970180.

- ^ a b c d e Burtis, Carl A.; Ashwood, Edward R.; Bruns, David E. (December 16, 2011). "44. Hematopoeitic malignancies". Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1371–1396. ISBN 978-1-4557-5942-2. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard Sheppard (2007). "Chapter 20: The Endocrine System". Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ a b Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM, Druker BJ, Talpaz M (May 2003). "Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics". Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (10): 819–30. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00010. PMID 12755554. S2CID 25865321.

- ^ a b Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard Sheppard (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 626. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ a b c Eykelenboom, Jennifer E; Briggs, Gareth J; Bradshaw, Nicholas J; Soares, Dinesh C; Ogawa, Fumiaki; Christie, Sheila; Malavasi, Elise LV; Makedonopoulou, Paraskevi; Mackie, Shaun; Malloy, Mary P; Wear, Martin A; Blackburn, Elizabeth A; Bramham, Janice; McIntosh, Andrew M; Blackwood, Douglas H (April 30, 2012). "A t(1;11) translocation linked to schizophrenia and affective disorders gives rise to aberrant chimeric DISC1 transcripts that encode structurally altered, deleterious mitochondrial proteins". Human Molecular Genetics. 21 (15): 3374–3386. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds169. PMC 3392113. PMID 22547224.

- ^ a b c "t(1;12)(q21;p13) ETV6/ARNT". atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ a b c Przybyl, Joanna; Sciot, Raf; Rutkowski, Piotr; Siedlecki, Janusz A.; Vanspauwen, Vanessa; Samson, Ignace; Debiec-Rychter, Maria (December 2012). "Recurrent and novel SS18-SSX fusion transcripts in synovial sarcoma: description of three new cases". Tumor Biology. 33 (6): 2245–2253. doi:10.1007/s13277-012-0486-0. PMC 3501176. PMID 22976541.

- ^ Eckel-Passow, Jeanette E.; Lachance, Daniel H.; Molinaro, Annette M.; Walsh, Kyle M.; Decker, Paul A.; Sicotte, Hugues; Pekmezci, Melike; Rice, Terri; Kosel, Matt L.; Smirnov, Ivan V.; Sarkar, Gobinda; Caron, Alissa A.; Kollmeyer, Thomas M.; Praska, Corinne E.; Chada, Anisha R. (June 25, 2015). "Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (26): 2499–2508. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407279. ISSN 1533-4406. PMC 4489704. PMID 26061753.

- ^ Cairncross, Gregory; Jenkins, Robert (November 2008). "Gliomas With 1p/19q Codeletion:a.k.a. Oligodendroglioma". The Cancer Journal. 14 (6): 352–357. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8178. PMID 19060598.

- ^ a b c Wu, Shuiyan; Lu, Jun; Su, Dongni; Yang, Fan; Zhang, Yongping; Hu, Shaoyan (March 2021). "The advantage of chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia with E2A-HLF fusion gene positivity: a case series". Translational Pediatrics. 10 (3): 686–691. doi:10.21037/tp-20-323. ISSN 2224-4344. PMC 8041607. PMID 33880339.

- ^ a b c Mohamed, Mustafa; Fisher, Cyril; Thway, Khin (June 2017). "Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: Clinical, morphologic and genetic features". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 28: 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2017.04.001. PMID 28648941.

External links

[edit] Media related to Chromosomal translocations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chromosomal translocations at Wikimedia Commons

Chromosomal translocation

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Definition

Chromosomal translocation is a type of structural chromosomal abnormality characterized by the rearrangement of genetic material between non-homologous chromosomes, where segments are exchanged or fused.[7] This rearrangement typically involves the breakage of chromosomes at specific points, followed by the incorrect rejoining of the broken segments in altered configurations, leading to a novel chromosomal structure.[8] Unlike other chromosomal abnormalities, translocation specifically entails the transfer of genetic material between different chromosomes, whereas deletions involve the loss of a chromosome segment, duplications result in extra copies of a segment, inversions reverse the orientation of a segment within the same chromosome, and aneuploidy refers to an abnormal number of chromosomes rather than structural changes.[9] These distinctions highlight translocation as a form of balanced or unbalanced exchange that alters gene positioning without necessarily changing the overall chromosome count.[10] Translocations can occur in somatic cells, affecting only the individual and potentially contributing to conditions like cancer, or in germ cells, where they may be inherited by offspring, leading to reproductive implications such as infertility or increased risk of unbalanced gametes.[11] Somatic translocations are acquired during life and not passed on, while germline translocations present from conception can propagate through generations if viable.[12]Classification

Chromosomal translocations are primarily classified as balanced or unbalanced based on whether there is a net loss or gain of genetic material. In balanced translocations, the exchange of chromosomal segments results in no overall alteration in the total amount of genetic material, although the arrangement is rearranged; carriers are typically phenotypically normal but may produce unbalanced gametes leading to reproductive issues.[13] Unbalanced translocations, in contrast, involve a net gain or loss of genetic material, resulting in partial aneuploidy that often causes clinical abnormalities such as developmental delays or congenital defects.[13] Translocations can be further classified into specific types based on the mechanism of exchange, such as reciprocal, nonreciprocal, and Robertsonian, as detailed in subsequent sections.Types of Translocations

Reciprocal Translocations

Reciprocal translocations are chromosomal abnormalities characterized by the mutual exchange of segments between two non-homologous chromosomes, typically involving breaks at specific points followed by the rejoining of the broken ends in a swapped configuration.[14] In balanced reciprocal translocations, the exchanged segments are of equal length, resulting in no net gain or loss of genetic material for the carrier, who is usually phenotypically normal.[15] However, during meiosis, the translocated chromosomes form a quadrivalent structure, which can segregate in ways that produce gametes with unbalanced chromosomal content, increasing the risk of miscarriage or offspring with genetic imbalances.[16] The process begins with double-strand breaks in the two chromosomes, followed by the reciprocal ligation of the resulting ends: for example, the distal segment of one chromosome's arm attaches to the other chromosome, and vice versa, creating two derivative chromosomes that together retain the full genome complement.[17] Unbalanced reciprocal translocations arise from unequal exchanges or from the inheritance of unbalanced gametes from a balanced carrier parent, leading to partial monosomy (loss of genetic material) or partial trisomy (gain of genetic material) in the offspring.[18] These partial aneuploidies disrupt gene dosage and can cause a range of effects, including developmental delay, intellectual disability, growth abnormalities, dysmorphic features, and congenital anomalies.[18] Balanced reciprocal translocations occur in approximately 1 in 500 individuals in the general population.[19] Such translocations are denoted using International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature, for example, t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) to indicate the chromosomes involved and breakpoint locations.[15]Nonreciprocal Translocations

Nonreciprocal translocations involve the unidirectional transfer of a chromosomal segment from one chromosome to a nonhomologous chromosome without any reciprocal exchange of genetic material.[20] This asymmetric process results in the donor chromosome losing the transferred segment, while the recipient chromosome gains it as an addition.[21] Unlike reciprocal translocations, which feature mutual exchanges that may preserve overall genetic balance, nonreciprocal events inherently produce unbalanced karyotypes.[20] The mechanisms underlying nonreciprocal translocations typically arise from errors in DNA repair following double-strand breaks (DSBs). These breaks can be induced by endogenous factors such as replication stress or exogenous agents like ionizing radiation, leading to improper rejoining of chromosome ends via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).[3] In NHEJ, the broken ends are ligated without significant homology, favoring one-way attachments where the segment from the donor integrates into the recipient without compensation.[22] This process often occurs during mitosis or meiosis, amplifying the risk of structural imbalance.[23] As a result, nonreciprocal translocations frequently lead to gene dosage imbalances, with partial deletions on the donor chromosome causing monosomy for affected genes and duplications on the recipient creating trisomy-like effects.[24] These alterations disrupt normal gene expression, potentially triggering cellular defects such as altered chromatin remodeling and increased transcription near breakpoints.[24] The unbalanced nature contributes to genomic instability, though such events are rarer than reciprocal translocations in constitutional settings.[25] In evolutionary contexts, nonreciprocal translocations have facilitated genetic duplications by allowing transferred segments to segregate during meiosis, promoting adaptive variations in species like plants.[26] They are also implicated in rare congenital syndromes, where de novo occurrences result in severe developmental disruptions due to the dosage imbalances.[27]Robertsonian Translocations

Robertsonian translocations involve the fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes at or near their centromeres, resulting in the loss of the short arms (p arms) of both chromosomes.[28] In humans, this type of translocation typically occurs between chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22, which are the acrocentric chromosomes.[29] The resulting structure is a single chromosome composed of the long arms (q arms) of the two original chromosomes, often denoted using notation such as rob(14;21) for a fusion between chromosomes 14 and 21.[28] Individuals who are balanced carriers of a Robertsonian translocation have 45 chromosomes instead of the usual 46, as the two long arms are joined into one chromosome.[30] These carriers are typically phenotypically normal because the short arms lost in the fusion contain primarily redundant ribosomal RNA genes located in the nucleolar organizer regions (NORs), which are present on multiple acrocentric chromosomes and thus not essential in single copies.[31] The prevalence of balanced Robertsonian translocation carriers in the general population is approximately 1 in 1,000 individuals.[30] Unbalanced Robertsonian translocations can arise during meiosis in carriers, leading to gametes with an extra copy of one of the involved chromosomes and thus a risk of trisomy in offspring.[28] For example, carriers of a t(14;21) translocation have an increased risk of having children with translocation Down syndrome (trisomy 21), where the offspring inherits the translocated chromosome plus a normal chromosome 21, resulting in three copies of the long arm of chromosome 21.[32] Such unbalanced outcomes account for about 3-4% of all cases of Down syndrome.[32]Mechanisms of Translocation

Structural Changes

Chromosomal translocations involve the exchange of genetic material between non-homologous chromosomes, resulting in the formation of derivative chromosomes that incorporate segments from the involved chromosomes. These derivative chromosomes, often denoted as der(X) or der(Y) where X and Y represent the chromosomes, arise from the physical swapping or fusion of chromosomal arms or segments, altering the overall architecture of the genome. In balanced translocations, such as those classified as reciprocal, the derivatives maintain the total genetic content without apparent loss or gain of material, though the rearrangement can disrupt gene function at breakpoints.[33] The structural impacts of these translocations manifest in several key aspects of chromosome organization. Banding patterns, which reflect the differential staining of chromosomal regions based on DNA composition, become visibly altered in derivative chromosomes, with segments from one chromosome appearing in the position of another, leading to irregular light and dark bands. Centromere positions may shift or duplicate, potentially creating dicentric chromosomes where two centromeres are present on a single derivative, which can cause instability during cell division due to anaphase bridge formation. Telomere integrity is also compromised in unbalanced cases, where terminal deletions may occur, necessitating stabilization through mechanisms like telomere capture or neotelomere formation to prevent further chromosomal degradation.[34][35][33] In karyotypic representations, translocations are depicted through standardized diagrams and banding analyses that highlight these alterations. G-banding, a common cytogenetic technique using Giemsa staining, reveals derivative chromosomes as structurally abnormal entities with mismatched banding sequences compared to normal homologs, allowing visualization of breakpoints at resolutions of 5-10 Mb. Ideograms, schematic illustrations of chromosome structures, further illustrate these changes by showing the relocated segments and modified arm lengths, providing a clear map of the rearranged karyotype for diagnostic purposes.[33][34] Differences between somatic and germline translocations influence their structural persistence and inheritance. Somatic translocations, occurring in non-reproductive cells, often result in mosaic karyotypes where only a subset of cells exhibit the derivative chromosomes, potentially leading to tissue-specific effects like those in cancer. In contrast, germline translocations are present in all cells from conception, producing uniform structural changes across the body and enabling transmission to offspring, which can manifest as constitutional chromosomal abnormalities.[34][33]DNA Repair and Breaks

Chromosomal translocations often initiate from DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which occur when both strands of the DNA helix are severed at the same locus.[36] These breaks can arise from exogenous sources such as ionizing radiation, which directly fragments DNA, or from chemicals like chemotherapeutic agents and industrial clastogens that induce strand cleavage.[37] Endogenously, DSBs form during replication fork stalling or collapse, where the replication machinery encounters obstacles leading to fork breakage.[38] The primary repair pathway for DSBs in mammalian cells is non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which ligates broken DNA ends without requiring sequence homology, often resulting in small insertions or deletions at the junction.[39] In NHEJ, the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds to DSB ends, recruiting DNA-PKcs and the ligase IV-XRCC4 complex to perform direct ligation; this process is inherently error-prone and can erroneously join DSBs from different chromosomes, promoting translocations.[40] The fidelity of NHEJ relies on minimal end processing, described simply as the direct rejoining of compatible ends without templated repair, which increases the risk of illegitimate ligation when multiple DSBs are present.[41] Alternative end-joining (Alt-EJ) pathways, including microhomology-mediated end joining, also contribute to translocations by utilizing short homologous sequences (typically 2-20 base pairs) at break ends for annealing after limited resection.[42] Alt-EJ is suppressed in normal cells but becomes prominent when classical NHEJ is deficient or overwhelmed, leading to higher rates of inter-chromosomal joins and complex rearrangements.[43] These pathways can produce derivative chromosomes through misrepair of spatially proximate breaks.[6] Several factors exacerbate DSB formation and promote translocation-prone repair, including oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species that oxidize DNA bases and generate clustered lesions.[44] Topoisomerase inhibition, such as by drugs like etoposide that trap enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes, stabilizes DSB intermediates and shifts repair toward error-prone mechanisms.[45]Nomenclature and Detection

Notation

The International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN) establishes the standardized conventions for denoting chromosomal translocations in cytogenetic descriptions, ensuring consistency across research and clinical reporting. This system uses specific symbols and formats to represent the chromosomes involved, their breakpoints, and the nature of the rearrangement. For reciprocal translocations, the primary symbol is "t", followed by parentheses enclosing the chromosome numbers separated by a semicolon, and a second set of parentheses specifying the breakpoint bands on the p (short) or q (long) arms, as in t(9;22)(q34;q11.2). Robertsonian translocations, involving fusion at or near the centromeres of acrocentric chromosomes, are denoted with "rob" in a similar format, such as rob(13;14)(q10;q10), where breakpoints are typically at the q10 position indicating the centromeric region. Distinctions in notation highlight whether a translocation is balanced or unbalanced, reflecting the absence or presence of net genetic material gain or loss. Balanced translocations are described solely with the "t" or "rob" designation, implying an equal exchange without detectable imbalance, as the total chromosome complement remains unchanged (e.g., 46 chromosomes in a typical human karyotype). Unbalanced translocations, conversely, incorporate the "der" symbol to identify the derivative chromosome bearing the abnormal segment, often accompanied by indications of additional or missing material, such as +der(22)t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) to denote gain of the derivative. Parentheses delineate breakpoints precisely, with sub-band levels (e.g., q11.2) providing resolution based on banding techniques, and the order of chromosomes follows numerical sequence unless specified otherwise. The evolution of this notation traces back to the 1970s, when international conferences addressed the need for uniform cytogenetic language amid growing discoveries of chromosomal abnormalities. The foundational standards emerged from the 1971 Paris Conference on Human Cytogenetics, leading to the first formal ISCN edition in 1978, which codified symbols like "t" and introduced structured breakpoint descriptions to replace ad hoc notations.[46] Subsequent revisions, such as those in 1985, 1995, 2005, 2013, 2016, 2020, and 2024, refined these rules to accommodate higher-resolution techniques while maintaining core principles for translocation representation. For instance, the 2024 edition incorporated nomenclature for optical genome mapping (OGM) to describe complex structural variants including translocations.[47] The notation t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) famously describes the Philadelphia chromosome associated with chronic myeloid leukemia.Detection Methods

Chromosomal translocations are commonly detected through conventional karyotyping, which involves staining and microscopic examination of metaphase chromosomes to visualize gross structural rearrangements such as balanced or unbalanced translocations larger than 5-10 megabases (Mb). G-banding, the most widely used karyotyping technique, relies on trypsin treatment followed by Giemsa staining to create characteristic light and dark bands, allowing identification of translocations by observing abnormal chromosome morphologies like derivative chromosomes.[48] However, its resolution is limited to detecting changes above approximately 5-10 Mb, making it insufficient for subtle or submicroscopic translocations, and it requires actively dividing cells, which can complicate analysis in certain tissues.[48] Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) enhances detection by using fluorescently labeled DNA probes that hybridize to specific chromosomal regions, enabling visualization of translocation breakpoints directly on metaphase or interphase nuclei without needing cell culture.[49] This method is particularly advantageous for confirming known translocations or identifying subtle rearrangements missed by karyotyping, as it offers higher resolution (down to 100-500 kilobases) and specificity for targeted loci, such as fusion genes in cancer-associated translocations like BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia.[50][51] FISH probes can be locus-specific, centromeric, or subtelomeric, providing morphological evidence of chromosomal abnormalities and allowing rapid analysis in non-dividing cells, though it requires prior knowledge of the suspected breakpoints and does not survey the entire genome.[49][51] Advanced genomic techniques have improved translocation detection, particularly for unbalanced cases and precise breakpoint mapping. Array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) compares patient DNA to a reference genome on a microarray to identify copy number variations, effectively detecting unbalanced translocations through gains or losses at derivative chromosome regions, with resolution down to 50-100 kilobases depending on probe density.[52][53] It excels in genome-wide screening but cannot identify balanced translocations without copy number changes.[53] Next-generation sequencing (NGS), including whole-genome sequencing variants developed post-2010, enables nucleotide-level resolution of breakpoints by aligning short or long reads to reference genomes, identifying structural variants like translocations through discordant read pairs or split reads, and has become essential for de novo discovery in complex cases.[54][55] Optical genome mapping (OGM) represents a more recent advancement, utilizing long-range optical imaging of DNA molecules labeled at specific motifs to detect structural variants, including translocations, with resolution around 30 kilobases for structural variants. Integrated into ISCN 2024, OGM is particularly useful for characterizing complex rearrangements and balanced translocations without relying on short reads.[56] These methods are applied differently in prenatal and postnatal screening. Prenatally, invasive procedures like amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling enable karyotyping, FISH, or array CGH to detect translocations in fetal cells, with array CGH offering higher diagnostic yield for unbalanced rearrangements compared to traditional karyotyping alone.[57][58] Postnatally, the same techniques are used on peripheral blood or tissue samples to investigate developmental delays or congenital anomalies, where NGS provides added value for precise breakpoint characterization in undiagnosed cases.[57][55]Clinical Significance

Role in Cancer

Chromosomal translocations contribute significantly to oncogenesis by generating oncogenic fusion genes that produce aberrant proteins, thereby activating dysregulated signaling pathways and promoting uncontrolled cell growth. These events are predominantly somatic, arising as acquired mutations in somatic cells during an individual's lifetime, rather than being inherited as germline variants, which are more commonly linked to constitutional genetic disorders. In hematologic malignancies, such translocations often result in chimeric proteins with constitutive kinase activity, exemplified by the BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), where the translocation fuses the BCR gene on chromosome 22 with the ABL1 gene on chromosome 9, leading to persistent activation of downstream pathways like RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT.[59][60] Translocations are prevalent in many leukemias and lymphomas, occurring in a substantial proportion of cases (e.g., over 50% in certain leukemia subtypes and around 40% in B-cell lymphomas), where they serve as primary drivers of disease by deregulating oncogenes through fusion or promoter juxtaposition.[61] This prevalence underscores their role as hallmark genetic alterations in these cancers, with somatic origins facilitating clonal expansion in response to DNA damage or replication stress. Detection via tumor karyotyping or molecular methods often reveals these rearrangements, informing risk stratification and treatment decisions.[62][63] Therapeutic targeting of translocation-induced fusions has transformed cancer management, particularly through tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that specifically inhibit the aberrant enzymatic activity of fusion proteins. For BCR-ABL-driven CML, imatinib exemplifies this approach by competitively binding the kinase domain, halting oncogenic signaling and inducing remission in the majority of patients, thereby establishing a paradigm for precision oncology in translocation-associated malignancies. Ongoing developments extend TKIs to other fusions, enhancing specificity and reducing off-target effects.[64][65]Role in Genetic Disorders

Chromosomal translocations occurring in the germline can lead to significant reproductive challenges for carriers, primarily due to abnormal segregation during meiosis. Balanced translocation carriers are phenotypically normal but produce a high proportion of unbalanced gametes as a result of aberrant chromosome pairing and separation in meiosis I. This segregation imbalance often follows patterns such as adjacent-1 or 3:1, resulting in gametes with partial trisomy or monosomy for segments of the involved chromosomes. Studies of preimplantation embryos from carriers have shown that approximately 50% may carry unbalanced karyotypes, with the remainder split between normal and balanced outcomes.[66] In Robertsonian translocation carriers, the fusion of acrocentric chromosomes increases the risk of unbalanced gametes that can result in trisomic offspring. These carriers face elevated rates of aneuploidy in viable pregnancies, contributing to associations with congenital syndromes characterized by extra chromosomal material. The theoretical risk stems from preferential segregation modes that favor unbalanced products, though empirical data indicate variable outcomes depending on the specific chromosomes involved.[30] Genetic counseling for translocation carriers focuses on assessing and communicating the risks of unbalanced offspring, recurrent miscarriages, and infertility to inform family planning. Counselors emphasize the estimation of recurrence probabilities, which can vary by translocation type and parental sex, and recommend prenatal testing options such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis to detect imbalances in pregnancies. Prenatal diagnosis is routinely offered to these families to enable informed decisions regarding continuation or termination of affected pregnancies. Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is increasingly used to select balanced or normal embryos, reducing the risk of unbalanced offspring.[16] Population-based studies estimate the carrier frequency of balanced chromosomal translocations at approximately 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000 individuals in the general population, with reciprocal translocations occurring at about 0.14% and Robertsonian types slightly more common. Empirical risks for liveborn unbalanced offspring vary widely but are generally low (typically 1-10% depending on the translocation and parental sex, higher in female carriers) and up to 10-15% for certain Robertsonian configurations, influencing the need for targeted screening in high-risk families. These frequencies underscore the importance of population genetics in identifying at-risk groups and tailoring preventive strategies.[16][67][68]Specific Examples

Translocations by Chromosome

Chromosomal translocations in humans are cataloged by the pairs of chromosomes involved, providing a framework for understanding karyotype variations across the 23 pairs. Numerous distinct translocations have been documented in cytogenetic databases, encompassing both Robertsonian and reciprocal types observed in diverse populations.[69] These rearrangements occur with a frequency of about 1 in 500 individuals in the general population for balanced forms, many of which are non-pathogenic and persist without phenotypic effects in healthy carriers.[67] Non-pathogenic balanced translocations, particularly those not disrupting critical genes, are prevalent in healthy individuals, with studies reporting rates up to 0.29% for balanced variants and 0.13% for unbalanced ones in screened cohorts.[70] Robertsonian translocations, involving fusion at or near the centromeres of acrocentric chromosomes (13, 14, 15, 21, 22), represent the most frequent structural variants, accounting for roughly 57% of translocations in population studies. The most common pair across broader studies is between chromosomes 13 and 14, denoted as rob(13q;14q), observed in approximately 0.97 per 1,000 newborns.[71] Other frequent Robertsonian pairs include 14 and 21 (rob(14q;21q)), comprising about 26% of cases in some cohorts, and 21 and 21 (rob(21q;21q)), at around 14%. Translocations involving 15 and 22 or 13 and 21 are less common but recurrent in healthy carriers.[67] Reciprocal translocations, involving exchanges between non-acrocentric or heterologous chromosomes, are more variable but often cluster around specific pairs in population data. The most recurrent constitutional reciprocal translocation is t(11;22)(q23;q11), identified as the predominant non-Robertsonian variant across global studies. Other common pairs include those involving chromosome 8 with 11 or 18 (e.g., t(8;11), t(8;18)), and 11 with 18 (t(11;18)), frequently noted in cytogenetic screenings. Pairs such as 1 with 13 or 4 with 5 also appear recurrently, with chromosomes 1, 11, and 13 being the most involved overall in reciprocal events.[72][67] Breakpoint hotspots in these translocations preferentially localize to the q arms of chromosomes, particularly in longer cytogenetic bands, and pericentromeric regions, facilitating the structural exchanges observed in karyotypes. For Robertsonian types, breaks cluster near centromeres in the short p arms of acrocentrics, while reciprocal breakpoints favor euchromatic q-arm segments.[73][74]| Translocation Type | Common Chromosome Pairs | Approximate Frequency in Populations | Example Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robertsonian | 13;14 | ~1/1,000 newborns | rob(13q;14q) |

| Robertsonian | 14;21 | 26% of Robertsonian cases | rob(14q;21q) |

| Robertsonian | 21;21 | 14% of Robertsonian cases | rob(21q;21q) |

| Reciprocal | 11;22 | Most frequent non-Robertsonian | t(11;22)(q23;q11) |

| Reciprocal | 8;11 | Recurrent in cohorts | t(8;11) |

| Reciprocal | 8;18 | Recurrent in cohorts | t(8;18) |

| Reciprocal | 11;18 | Recurrent in cohorts | t(11;18) |