Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ionizing radiation

View on Wikipedia

Ionizing radiation, also spelled ionising radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionize atoms or molecules by detaching electrons from them.[1] Some particles can travel up to 99% of the speed of light, and the electromagnetic waves are on the high-energy portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Gamma rays, X-rays, and the higher energy ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum are ionizing radiation; whereas the lower energy ultraviolet, visible light, infrared, microwaves, and radio waves are non-ionizing radiation. Nearly all types of laser light are non-ionizing radiation. The boundary between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation in the ultraviolet area cannot be sharply defined, as different molecules and atoms ionize at different energies. The energy of ionizing radiation starts around 10 electronvolts (eV).[2]

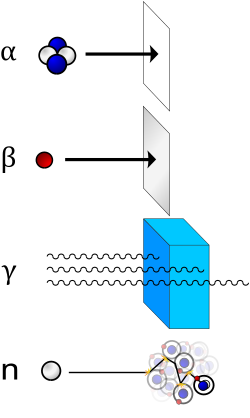

Ionizing subatomic particles include alpha particles, beta particles, and neutrons. These particles are created by radioactive decay, and almost all are energetic enough to ionize. There are also secondary cosmic particles produced after cosmic rays interact with Earth's atmosphere, including muons, mesons, and positrons.[3][4] Cosmic rays may also produce radioisotopes on Earth (for example, carbon-14), which in turn decay and emit ionizing radiation. Cosmic rays and the decay of radioactive isotopes are the primary sources of natural ionizing radiation on Earth, contributing to background radiation. Ionizing radiation is also generated artificially by X-ray tubes, particle accelerators, and nuclear fission.

Ionizing radiation is not immediately detectable by human senses, so instruments such as Geiger counters are used to detect and measure it. However, very high energy particles can produce visible effects on both organic and inorganic matter (e.g. water lighting in Cherenkov radiation) or humans (e.g. acute radiation syndrome).[5]

Ionizing radiation is used in a wide variety of fields such as medicine, nuclear power, research, and industrial manufacturing, but is a health hazard if proper measures against excessive exposure are not taken. Exposure to ionizing radiation causes cell damage to living tissue and organ damage. In high acute doses, it will result in radiation burns and radiation sickness, and lower level doses over a protracted time can cause cancer.[6][7] The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) issues guidance on ionizing radiation protection, and the effects of dose uptake on human health.

Directly ionizing radiation

[edit]

Ionizing radiation may be grouped as directly or indirectly ionizing.

Any charged particle with mass can ionize atoms directly by fundamental interaction through the Coulomb force if it has enough kinetic energy. Such particles include atomic nuclei, electrons, muons, charged pions, protons, and energetic charged nuclei stripped of their electrons. When moving at relativistic speeds (near the speed of light, c) these particles have enough kinetic energy to be ionizing, but there is considerable speed variation. For example, a typical alpha particle moves at about 5% of c, but an electron with 33 eV (just enough to ionize) moves at about 1% of c.

Two of the first types of directly ionizing radiation to be discovered are alpha particles which are helium nuclei ejected from the nucleus of an atom during radioactive decay, and energetic electrons, which are called beta particles.

Natural cosmic rays are made up primarily of relativistic protons but also include heavier atomic nuclei like helium ions and HZE ions. In the atmosphere such particles are often stopped by air molecules, and this produces short-lived charged pions, which soon decay to muons, a primary type of cosmic ray radiation that reaches the surface of the earth. Pions can also be produced in large amounts in particle accelerators.

Alpha particles

[edit]Alpha (α) particles consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle: a helium-4 nucleus. Alpha particle emissions are generally produced in the process of alpha decay.

Alpha particles are a strongly ionizing form of radiation, but when emitted by radioactive decay they have low penetration power and can be absorbed by a few centimeters of air, or by the top layer of human skin. More powerful alpha particles from ternary fission are three times as energetic, and penetrate proportionately farther in air. The helium nuclei that form 10–12% of cosmic rays, are also usually of much higher energy than those from radioactive decay and pose shielding problems in space. However, this type of radiation is significantly absorbed by Earth's atmosphere, which is a radiation shield equivalent to about 10 meters of water.[8]

The alpha particle was named by Ernest Rutherford after the first letter in the Greek alphabet, α, when he ranked the known radioactive emissions in descending order of ionizing effect in 1899. The symbol is α or α2+. Because they are identical to helium nuclei, they are also called He2+ or 4

2He2+

indicating helium with a charge of +2 e (missing its two electrons). If the ion gains electrons from its environment, the α particle can be written as a normal (electrically neutral) helium atom 4

2He.

Beta particles

[edit]Beta (β) particles are high-energy, high-speed electrons or positrons emitted by certain types of radioactive nuclei, such as potassium-40. The production of β particles is termed beta decay. There are two forms of β decay, β− and β+, which respectively give rise to the electron and the positron.[9] Beta particles are much less penetrating than gamma radiation, but more penetrating than alpha particles.

High-energy beta particles may produce X-rays known as bremsstrahlung ("braking radiation") or secondary electrons (delta ray) as they pass through matter. Both of these can cause an indirect ionization effect. Bremsstrahlung is of concern when shielding beta emitters, as the interaction of beta particles with some shielding materials produces bremsstrahlung. The effect is greater with material having high atomic numbers, so material with low atomic numbers is used for beta source shielding.

Positrons and other types of antimatter

[edit]The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. When a low-energy positron collides with a low-energy electron, annihilation occurs, resulting in their conversion into the energy of two or more gamma ray photons (see electron–positron annihilation). As positrons are positively charged particles they can directly ionize an atom through Coulomb interactions.

Positrons can be generated by positron emission nuclear decay (through weak interactions), or by pair production from a sufficiently energetic photon. Positrons are common artificial sources of ionizing radiation used in medical positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

Charged nuclei

[edit]Charged nuclei are characteristic of galactic cosmic rays and solar particle events and except for alpha particles (charged helium nuclei) have no natural sources on Earth. In space, however, very high energy protons, helium nuclei, and HZE ions can be initially stopped by relatively thin layers of shielding, clothes, or skin. However, the resulting interaction will generate secondary radiation and cause cascading biological effects. If just one atom of tissue is displaced by an energetic proton, for example, the collision will cause further interactions in the body. This is called "linear energy transfer" (LET), which utilizes elastic scattering.

LET can be visualized as a billiard ball hitting another in the manner of the conservation of momentum, sending both away with the energy of the first ball divided between the two unequally. When a charged nucleus strikes a relatively slow-moving nucleus of an object in space, LET occurs and neutrons, alpha particles, low-energy protons, and other nuclei will be released by the collisions and contribute to the total absorbed dose of tissue.[10]

Indirectly ionizing radiation

[edit]Indirectly ionizing radiation is electrically neutral and does not interact strongly with matter, therefore the bulk of the ionization effects are due to secondary ionization.

Photon radiation

[edit]

Even though photons are electrically neutral, they can ionize atoms indirectly through the photoelectric effect and the Compton effect. Either of those interactions cause the ejection of an electron from an atom at relativistic speeds, turning that electron into a (secondary) beta particle that will ionize other atoms. Since most of the ionized atoms are due to the secondary beta particles, photons are indirectly ionizing radiation.[11]

Radiated photons are called gamma rays if they are produced by a nuclear reaction, subatomic particle decay, or radioactive decay within the nucleus. They are called x-rays if produced outside the nucleus. The generic term "photon" is used to describe both.[12][13][14]

X-rays normally have a lower energy than gamma rays, and an older convention was to define the boundary as a wavelength of 10−11 m (or a photon energy of 100 keV).[15] That threshold was driven by historic limitations of older X-ray tubes and low awareness of isomeric transitions. Modern technologies and discoveries have shown an overlap between X-ray and gamma energies. In many fields they are functionally identical, differing for terrestrial studies only in origin of the radiation. In astronomy, however, where radiation origin often cannot be reliably determined, the old energy division has been preserved, with X-rays defined as being between about 120 eV and 120 keV, and gamma rays as being of any energy above 100 to 120 keV, regardless of source. Most astronomical "gamma-rays" are known not to originate from radioactivity but, rather, result from processes like those that produce astronomical X-rays, except driven by much more energetic electrons.

Photoelectric absorption is the dominant mechanism in organic materials for photon energies below 100 keV, typical of classical X-ray tube originated X-rays. At energies beyond 100 keV, photons ionize matter increasingly through the Compton effect, and then indirectly through pair production at energies beyond 5 MeV. The accompanying interaction diagram shows two Compton scatterings happening sequentially. In every scattering event, the gamma ray transfers energy to an electron, and it continues on its path in a different direction and with reduced energy.

Definition boundary for lower-energy photons

[edit]The lowest ionization energy of any element is 3.89 eV, for caesium. However, US Federal Communications Commission material defines ionizing radiation as that with a photon energy greater than 10 eV (equivalent to a far ultraviolet wavelength of 124 nanometers).[2] Roughly, this corresponds to both the first ionization energy of oxygen, and the ionization energy of hydrogen, both about 14 eV.[16] In some Environmental Protection Agency references, the ionization of a typical water molecule at an energy of 33 eV is referenced[17] as the appropriate biological threshold for ionizing radiation: this value represents the so-called W-value, the colloquial name for the ICRU's mean energy expended in a gas per ion pair formed,[18] which combines ionization energy plus the energy lost to other processes such as excitation.[19] At 38 nanometers wavelength for electromagnetic radiation, 33 eV is close to the energy at the conventional 10 nm wavelength transition between extreme ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, which occurs at about 125 eV. Thus, X-ray radiation is always ionizing, but only extreme-ultraviolet radiation can be considered ionizing under all definitions.

Neutrons

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

Neutrons have a neutral electrical charge often misunderstood as zero electrical charge and thus often do not directly cause ionization in a single step or interaction with matter. However, fast neutrons will interact with the protons in hydrogen via linear energy transfer, energy that a particle transfers to the material it is moving through. This mechanism scatters the nuclei of the materials in the target area, causing direct ionization of the hydrogen atoms. When neutrons strike the hydrogen nuclei, proton radiation (fast protons) results. These protons are themselves ionizing because they are of high energy, are charged, and interact with electrons.

Neutrons that strike other nuclei besides hydrogen, transfer less energy to the other particle if linear energy transfer does occur. But, for many nuclei struck by neutrons, inelastic scattering occurs. Whether elastic or inelastic scatter occurs is dependent on the speed of the neutron, whether fast or thermal or somewhere in between. It is also dependent on the nuclei it strikes and its neutron cross section.

In inelastic scattering, neutrons are readily absorbed in a type of nuclear reaction called neutron capture and attributes to the neutron activation of the nucleus. Neutron interactions with most types of matter in this manner usually produce radioactive nuclei. Oxygen-16, for example, undergoes neutron activation, rapidly decays by a proton emission forming nitrogen-16, which decays to oxygen-16. The short-lived nitrogen-16 decay emits a powerful beta ray. This process can be written as:

16O (n,p) 16N (fast neutron capture possible with >11 MeV neutron)

16N → 16O + β− (Decay t1/2 = 7.13 s)

This high-energy β− further interacts rapidly with other nuclei, emitting high-energy γ via Bremsstrahlung

While not a favorable reaction, the 16O (n,p) 16N reaction is a major source of X-rays emitted from the cooling water of a pressurized water reactor and contributes enormously to the radiation generated by a water-cooled nuclear reactor while operating.

For the best shielding of neutrons, hydrocarbons that have an abundance of hydrogen are used.

In fissile materials, secondary neutrons may produce nuclear chain reactions, causing a larger amount of ionization from the daughter products of fission.

Outside the nucleus, free neutrons are unstable and have a mean lifetime of 14 minutes, 42 seconds. Free neutrons decay by emission of an electron and an electron antineutrino to become a proton, a process known as beta decay:[20]

In the adjacent diagram, a neutron collides with a proton of the target material, and then becomes a fast recoil proton that ionizes in turn. At the end of its path, the neutron is captured by a nucleus in an (n,γ)-reaction that leads to the emission of a neutron capture photon. Such photons always have enough energy to qualify as ionizing radiation.

Physical effects

[edit]

Nuclear effects

[edit]Neutron radiation, alpha radiation, and extremely energetic gamma (> ~20 MeV) can cause nuclear transmutation and induced radioactivity. The relevant mechanisms are neutron activation, alpha absorption, and photodisintegration. A large enough number of transmutations can change macroscopic properties and cause targets to become radioactive themselves, even after the original source is removed.

Chemical effects

[edit]Ionization of molecules can lead to radiolysis (breaking chemical bonds), and formation of highly reactive free radicals. These free radicals may then react chemically with neighbouring materials even after the original radiation has stopped (e.g. ozone cracking of polymers by ozone formed by ionization of air). Ionizing radiation can also accelerate existing chemical reactions such as polymerization and corrosion, by contributing to the activation energy required for the reaction. Optical materials deteriorate under the effect of ionizing radiation.

High-intensity ionizing radiation in air can produce a visible ionized air glow of telltale bluish-purple color. The glow can be observed, e.g., during criticality accidents, around mushroom clouds shortly after a nuclear explosion, or the inside of a damaged nuclear reactor like during the Chernobyl disaster.

Monatomic fluids, e.g. molten sodium, have no chemical bonds to break and no crystal lattice to disturb, so they are immune to the chemical effects of ionizing radiation. Simple diatomic compounds with very negative enthalpy of formation, such as hydrogen fluoride will reform rapidly and spontaneously after ionization.

Electrical effects

[edit]The ionization of materials temporarily increases their conductivity, potentially permitting damaging current levels. This is a particular hazard in semiconductor microelectronics used in electronic equipment; subsequent currents introduce operation errors or even permanently damage the devices. Devices intended for high-radiation environments such as the nuclear industry or outer space, may be made radiation hard to resist such effects through design, material selection, and fabrication methods.

Ionizing radiation can cause an increase in the density of interface traps by reactivating passivated dangling bonds at interfaces between two materials, such as the Si/SiO2 interface in CMOS devices.[21] These traps can capture charge carriers, resulting in parasitic effects including mobility degradation, increased noise, and threshold voltage shifts.

Proton radiation found in space can also cause single-event upsets in digital circuits. The electrical effects of ionizing radiation are exploited in gas-filled radiation detectors, e.g. the Geiger counter or the ion chamber.

Health effects

[edit]Most adverse health effects of exposure to ionizing radiation may be grouped in two general categories:

- deterministic effects (harmful tissue reactions) due in large part to killing or malfunction of cells following high doses from radiation burns.

- stochastic effects, i.e., cancer and heritable effects involving either cancer development in exposed individuals owing to mutation of somatic cells or heritable disease in their offspring owing to mutation of reproductive (germ) cells.[22]

The most common impact is stochastic radiation-induced cancer with a latent period of years or decades after exposure. For example, ionizing radiation is one cause of chronic myelogenous leukemia,[23][24][25] although most people with CML have not been exposed to radiation.[24][25] The mechanism by which this occurs is well understood, but quantitative models predicting the level of risk remain controversial.[citation needed]

The most widely accepted model, the linear no-threshold model (LNT), holds that the incidence of cancers due to ionizing radiation increases linearly with effective radiation dose at a rate of 5.5% per sievert.[26] If this is correct, then natural background radiation is the most hazardous source of radiation to general public health, followed by medical imaging as a close second. Other stochastic effects of ionizing radiation are teratogenesis, cognitive decline, and heart disease.[citation needed]

Though DNA is always susceptible to damage by ionizing radiation, the DNA molecule may also be damaged by radiation with enough energy to excite certain molecular bonds to form pyrimidine dimers. This energy may be less than ionizing, but near to it. A good example is ultraviolet spectrum energy which begins at about 3.1 eV (400 nm) at close to the same energy level which can cause sunburn to unprotected skin, as a result of photoreactions in collagen and (in the UV-B range) also damage in DNA (for example, pyrimidine dimers). Thus, the mid and lower ultraviolet electromagnetic spectrum is damaging to biological tissues as a result of electronic excitation in molecules which falls short of ionization, but produces similar non-thermal effects. To some extent, visible light and also ultraviolet A (UVA) which is closest to visible energies, have been proven to result in formation of reactive oxygen species in skin, which cause indirect damage since these are electronically excited molecules which can inflict reactive damage, although they do not cause sunburn (erythema).[27] Like ionization-damage, all these effects in skin are beyond those produced by simple thermal effects.[citation needed]

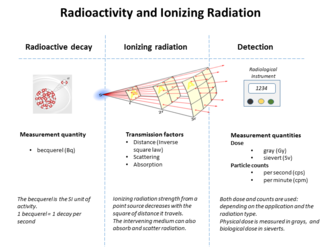

Measurement of radiation

[edit]

The table below shows radiation and dose quantities in SI and non-SI units.

| Quantity | Detector | CGS units | SI units | Other units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disintegration rate | curie | becquerel | ||

| Particle flux | Geiger counter, proportional counter, scintillator | counts/cm2 · second | counts/metre2 · second | counts per minute, particles per cm2 per second |

| Energy fluence | thermoluminescent dosimeter, film badge dosimeter | MeV/cm2 | joule/metre2 | |

| Beam energy | proportional counter | electronvolt | joule | |

| Linear energy transfer | derived quantity | MeV/cm | Joule/metre | keV/μm |

| Kerma | ionization chamber, semiconductor detector, quartz fiber dosimeter, Kearny fallout meter | esu/cm3 | gray (joule/kg) | roentgen |

| Absorbed dose | calorimeter | rad | gray | rep |

| Equivalent dose | derived quantity | rem | sievert (joule/kg × WR) | |

| Effective dose | derived quantity | rem | sievert (joule/kg × WR × WT) | BRET |

| Committed dose | derived quantity | rem | sievert | banana equivalent dose |

Uses of radiation

[edit]Ionizing radiation has many industrial, military, and medical uses. Its usefulness must be balanced with its hazards, a compromise that has shifted over time. For example, at one time, assistants in shoe shops in the US used X-rays to check a child's shoe size, but this practice was halted when the risks of ionizing radiation were better understood.[29]

Neutron radiation is essential to the working of nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. The penetrating power of x-ray, gamma, beta, and positron radiation is used for medical imaging, nondestructive testing, and a variety of industrial gauges. Radioactive tracers are used in medical and industrial applications, as well as biological and radiation chemistry. Alpha radiation is used in static eliminators and smoke detectors. The sterilizing effects of ionizing radiation are useful for cleaning medical instruments, food irradiation, and the sterile insect technique. Measurements of carbon-14, is used for radiocarbon dating.

Sources of radiation

[edit]Ionizing radiation is generated through nuclear reactions, nuclear decay, by very high temperature, or via acceleration of charged particles in electromagnetic fields. Natural sources include the Sun, lightning and supernova explosions. Artificial sources include nuclear reactors, particle accelerators, and x-ray tubes.

The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) itemized types of human exposures.

| Public exposure | ||

| Natural Sources | Normal occurrences | Cosmic radiation |

| Terrestrial radiation | ||

| Enhanced sources | Metal mining and smelting | |

| Phosphate industry | ||

| Coal mining and power production from coal | ||

| Oil and gas drilling | ||

| Rare earth and titanium dioxide industries | ||

| Zirconium and ceramics industries | ||

| Application of radium and thorium | ||

| Other exposure situations | ||

| Human-made sources | Peaceful purposes | Nuclear power production |

| Transport of nuclear and radioactive material | ||

| Application other than nuclear power | ||

| Military purposes | Nuclear tests | |

| Residues in the environment. Nuclear fallout | ||

| Historical situations | ||

| Exposure from accidents | ||

| Occupational radiation exposure | ||

| Natural Sources | Cosmic ray exposures of aircrew and space crew | |

| Exposures in extractive and processing industries | ||

| Gas and oil extraction industries | ||

| Radon exposure in workplaces other than mines | ||

| Human-made sources | Peaceful purposes | Nuclear power industries |

| Medical uses of radiation | ||

| Industrial uses of radiation | ||

| Miscellaneous uses | ||

| Military purposes | Other exposed workers | |

| Source UNSCEAR 2008 Annex B retrieved 2011-7-4 | ||

The International Commission on Radiological Protection manages the International System of Radiological Protection, which sets recommended limits for dose uptake.

Background radiation

[edit]Background radiation comes from both natural and human-made sources.

The global average exposure of humans to ionizing radiation is about 3 mSv (0.3 rem) per year, 80% of which comes from nature. The remaining 20% results from exposure to human-made radiation sources, mainly medical imaging. Average human-made exposure is much higher in developed countries, mostly due to CT scans and nuclear medicine.

Natural background radiation comes from five primary sources: cosmic radiation, solar radiation, external terrestrial sources, radiation in the human body, and radon.

The background rate for natural radiation varies considerably with location, being as low as 1.5 mSv/a (1.5 mSv per year) in some areas and over 100 mSv/a in others. The highest level of purely natural radiation recorded on the Earth's surface is 90 μGy/h (0.8 Gy/a) on a Brazilian black beach composed of monazite.[30] The highest background radiation in an inhabited area is found in Ramsar, mainly due to naturally radioactive limestone used as a building material. Some 2000 of the most exposed residents receive an average radiation dose of 10 mGy per year, (1 rad/yr) ten times more than the ICRP recommended limit for exposure to the public from artificial sources.[31] Record levels were found in a house where the effective radiation dose due to external radiation was 135 mSv/a, (13.5 rem/yr) and the committed dose from radon was 640 mSv/a (64.0 rem/yr).[32] This unique case is over 200 times higher than the world average background radiation. Despite the high levels of background radiation that the residents of Ramsar receive there is no compelling evidence that they experience a greater health risk. The ICRP recommendations are conservative limits and may represent an over representation of the actual health risk. Generally radiation safety organization recommend the most conservative limits assuming it is best to err on the side of caution. This level of caution is appropriate but should not be used to create fear about background radiation danger. Radiation danger from background radiation may be a serious threat but is more likely a small overall risk compared to all other factors in the environment.

Cosmic radiation

[edit]The Earth, and all living things on it, are constantly bombarded by radiation from outside the Solar System. This cosmic radiation consists of relativistic particles: positively charged nuclei (ions) from 1 Da protons (about 85% of it) to ~56 Da iron nuclei and even beyond. (The high-atomic number particles are called HZE ions.) The energy of this radiation can far exceed that which humans can create, even in the largest particle accelerators (see ultra-high-energy cosmic ray). This radiation interacts in the atmosphere to create secondary radiation that rains down, including x-rays, muons, protons, antiprotons, alpha particles, pions, electrons, positrons, and neutrons.

The dose from cosmic radiation is largely from muons, neutrons, and electrons, with a dose rate that varies in different parts of the world and based largely on the geomagnetic field, altitude, and solar cycle. The cosmic-radiation dose rate on airplanes is so high that, according to the United Nations UNSCEAR 2000 Report (see links at bottom), airline flight crew workers receive more dose on average than any other worker, including those in nuclear power plants. Airline crews receive more cosmic rays if they routinely work flight routes that take them close to the North or South pole at high altitudes, where this type of radiation is maximal.

Cosmic rays also include high-energy gamma rays, which are far beyond the energies produced by solar or human sources.

External terrestrial sources

[edit]Most materials on Earth contain some radioactive atoms, even if in small quantities. Most of the dose received from these sources is from gamma-ray emitters in building materials, or rocks and soil when outside. The major radionuclides of concern for terrestrial radiation are isotopes of potassium, uranium, and thorium. Each of these sources has been decreasing in activity since the formation of the Earth.

Internal radiation sources

[edit]All earthly materials that are the building blocks of life contain a radioactive component. As organisms consume food, air, and water, an inventory of radioisotopes builds up within the organism (see banana equivalent dose). Some radionuclides, like potassium-40, emit a high-energy gamma ray that can be measured by sensitive electronic radiation measurement systems. These internal radiation sources contribute to an individual's total radiation dose from natural background radiation.

Radon

[edit]An important source of natural radiation is radon gas, which seeps continuously from bedrock but can, because of its high density, accumulate in poorly ventilated houses.

Radon-222 is a gas produced by the α-decay of radium-226. Both are a part of the natural uranium decay chain. Uranium is found in soil throughout the world in varying concentrations. Radon is the largest cause of lung cancer among non-smokers and the second-leading cause overall.[33]

Radiation exposure

[edit]

There are three standard ways to limit exposure:

- Time: For people exposed to radiation in addition to natural background radiation, limiting or minimizing the exposure time will reduce the dose from the source of radiation.

- Distance: Radiation intensity decreases sharply with distance, according to an inverse-square law (in an absolute vacuum).[34]

- Shielding: Air or skin can be sufficient to substantially attenuate alpha radiation, while sheet metal or plastic is often sufficient to stop beta radiation. Barriers of lead, concrete, or water are often used to give effective protection from more penetrating forms of ionizing radiation such as gamma rays and neutrons. Some radioactive materials are stored or handled underwater or by remote control in rooms constructed of thick concrete or lined with lead. There are special plastic shields that stop beta particles, and air will stop most alpha particles. The effectiveness of a material in shielding radiation is determined by its half-value thicknesses, the thickness of material that reduces the radiation by half. This value is a function of the material itself and of the type and energy of ionizing radiation. Some generally accepted thicknesses of attenuating material are 5 mm of aluminum for most beta particles, and 3 inches of lead for gamma radiation.

These can all be applied to natural and human-made sources. For human-made sources the use of Containment is a major tool in reducing dose uptake and is effectively a combination of shielding and isolation from the open environment. Radioactive materials are confined in the smallest possible space and kept out of the environment such as in a hot cell (for radiation) or glove box (for contamination). Radioactive isotopes for medical use, for example, are dispensed in closed handling facilities, usually gloveboxes, while nuclear reactors operate within closed systems with multiple barriers that keep the radioactive materials contained. Work rooms, hot cells and gloveboxes have slightly reduced air pressures to prevent escape of airborne material to the open environment.

In nuclear conflicts or civil nuclear releases civil defense measures can help reduce exposure of populations by reducing ingestion of isotopes and occupational exposure. One is the issue of potassium iodide (KI) tablets, which blocks the uptake of radioactive iodine (one of the major radioisotope products of nuclear fission) into the human thyroid gland.

Occupational exposure

[edit]Occupationally exposed individuals are controlled within the regulatory framework of the country they work in, and in accordance with any local nuclear licence constraints. These are usually based on the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. The ICRP recommends limiting artificial irradiation. For occupational exposure, the limit is 50 mSv in a single year with a maximum of 100 mSv in a consecutive five-year period.[26]

The radiation exposure of these individuals is carefully monitored with the use of dosimeters and other radiological protection instruments which will measure radioactive particulate concentrations, area gamma dose readings and radioactive contamination. A legal record of dose is kept.

Examples of activities where occupational exposure is a concern include:

- Airline crew (the most exposed population)

- Industrial radiography

- Medical radiology and nuclear medicine[35][36]

- Uranium mining

- Nuclear power plant and nuclear fuel reprocessing plant workers

- Research laboratories (government, university and private)

Some human-made radiation sources affect the body through direct radiation, known as effective dose (radiation) while others take the form of radioactive contamination and irradiate the body from within. The latter is known as committed dose.

Public exposure

[edit]Medical procedures, such as diagnostic X-rays, nuclear medicine, and radiation therapy are by far the most significant source of human-made radiation exposure to the general public. Some of the major radionuclides used are I-131, Tc-99m, Co-60, Ir-192, and Cs-137. The public is also exposed to radiation from consumer products, such as tobacco (polonium-210), combustible fuels (gas, coal, etc.), televisions, luminous watches and dials (tritium), airport X-ray systems, smoke detectors (americium), electron tubes, and gas lantern mantles (thorium).

Of lesser magnitude, members of the public are exposed to radiation from the nuclear fuel cycle, which includes the entire sequence from processing uranium to the disposal of the spent fuel. The effects of such exposure have not been reliably measured due to the extremely low doses involved. Opponents use a cancer per dose model to assert that such activities cause several hundred cases of cancer per year, an application of the widely accepted Linear no-threshold model (LNT).

The International Commission on Radiological Protection recommends limiting artificial irradiation to the public to an average of 1 mSv (0.001 Sv) of effective dose per year, not including medical and occupational exposures.[26]

In a nuclear war, gamma rays from both the initial weapon explosion and fallout would be sources of radiation exposure.

Spaceflight

[edit]Massive particles are a concern for astronauts outside the Earth's magnetic field who would receive solar particles from solar proton events (SPE) and galactic cosmic rays from cosmic sources. These high-energy charged nuclei are blocked by Earth's magnetic field but pose a major health concern for astronauts traveling to the Moon and to any distant location beyond Earth orbit. Highly charged HZE ions in particular are known to be extremely damaging, though protons make up the vast majority of galactic cosmic rays. Evidence indicates past SPE radiation levels that would have been lethal for unprotected astronauts.[37]

Air travel

[edit]Air travel exposes people on aircraft to increased radiation from space as compared to sea level, including cosmic rays and from solar flare events.[38][39] Software programs such as Epcard, CARI, SIEVERT, PCAIRE are attempts to simulate exposure by aircrews and passengers.[39] An example of a measured dose (not simulated dose) is 6 μSv per hour from London Heathrow to Tokyo Narita on a polar route.[39] However, dosages can vary, such as during periods of high solar activity.[39] The United States FAA requires airlines to provide flight crew with information about cosmic radiation, and an International Commission on Radiological Protection recommendation for the general public is no more than 1 mSv per year.[39] Also, many airlines do not allow pregnant flightcrew members, to comply with a European Directive.[39] The FAA has a recommended limit of 1 mSv total for a pregnancy, and no more than 0.5 mSv per month.[39] Information originally based on Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine published in 2008.[39]

Radiation hazard warning signs

[edit]Hazardous levels of ionizing radiation are signified by the trefoil sign on a yellow background. These are usually posted at the boundary of a radiation controlled area or in any place where radiation levels are significantly above background due to human intervention.

The red ionizing radiation warning symbol (ISO 21482) was launched in 2007, and is intended for IAEA Category 1, 2 and 3 sources defined as dangerous sources capable of death or serious injury, including food irradiators, teletherapy machines for cancer treatment and industrial radiography units. The symbol is to be placed on the device housing the source, as a warning not to dismantle the device or to get any closer. It will not be visible under normal use, only if someone attempts to disassemble the device. The symbol will not be located on building access doors, transportation packages or containers.[40]

-

Ionizing radiation hazard symbol

-

2007 ISO radioactivity danger symbol intended for IAEA Category 1, 2 and 3 sources defined as dangerous sources capable of death or serious injury.[40]

See also

[edit]- European Committee on Radiation Risk

- International Commission on Radiological Protection – manages the International System of Radiological Protection

- Ionometer

- Irradiated mail

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements – US national organisation

- Nuclear safety

- Nuclear semiotics

- Radiant energy

- Exposure (radiation)

- Radiation hormesis

- Radiation physics

- Radiation protection

- Radiation Protection Convention, 1960

- Radiation protection of patients

- Sievert

- Treatment of infections after accidental or hostile exposure to ionizing radiation

References

[edit]- ^ "Ionizing radiation, health effects and protective measures". World Health Organization. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b Robert F. Cleveland, Jr.; Jerry L. Ulcek (August 1999). "Questions and Answers about Biological Effects and Potential Hazards of Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields" (PDF) (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: OET (Office of Engineering and Technology) Federal Communications Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-20. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ^ Woodside, Gayle (1997). Environmental, Safety, and Health Engineering. US: John Wiley & Sons. p. 476. ISBN 978-0471109327. Archived from the original on 2015-10-19.

- ^ Stallcup, James G. (2006). OSHA: Stallcup's High-voltage Telecommunications Regulations Simplified. US: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 133. ISBN 978-0763743475. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17.

- ^ "Ionizing Radiation - Health Effects | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- ^ Ryan, Julie (5 January 2012). "Ionizing Radiation: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 132 (3 0 2): 985–993. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.411. PMC 3779131. PMID 22217743.

- ^ Herrera Ortiz AF, Fernández Beaujon LJ, García Villamizar SY, Fonseca López FF. Magnetic resonance versus computed tomography for the detection of retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis due to testicular cancer: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Radiology Open.2021;8:100372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2021.100372

- ^ One kg of water per cm squared is 10 meters of water Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Beta Decay". Lbl.gov. 9 August 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Contribution of High Charge and Energy (HZE) Ions During Solar-Particle Event of September 29, 1989 Kim, Myung-Hee Y.; Wilson, John W.; Cucinotta, Francis A.; Simonsen, Lisa C.; Atwell, William; Badavi, Francis F.; Miller, Jack, NASA Johnson Space Center; Langley Research Center, May 1999.

- ^ European Centre of Technological Safety. "Interaction of Radiation with Matter" (PDF). Radiation Hazard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^

Feynman, Richard; Robert Leighton; Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol.1. USA: Addison-Wesley. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-201-02116-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ L'Annunziata, Michael; Mohammad Baradei (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-12-436603-9. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Grupen, Claus; G. Cowan; S. D. Eidelman; T. Stroh (2005). Astroparticle Physics. Springer. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-540-25312-9.

- ^ Charles Hodgman, Ed. (1961). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 44th Ed. USA: Chemical Rubber Co. p. 2850.

- ^ Jim Clark (2000). "Ionisation Energy". Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ^ "Ionizing & Non-Ionizing Radiation". Radiation Protection. EPA. 2014-07-16. Archived from the original on 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ^ "Fundamental Quantities and Units for Ionizing Radiation (ICRU Report 85)". Journal of the ICRU. 11 (1). 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-04-20.

- ^ Hao Peng. "Gas Filled Detectors" (PDF). Lecture notes for MED PHYS 4R06/6R03 – Radiation & Radioisotope Methodology. MacMaster University, Department of Medical Physics and Radiation Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-17.

- ^ W.-M. Yao; et al. (2007). "Particle Data Group Summary Data Table on Baryons" (PDF). J. Phys. G. 33 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ^ Khoshnoud, A.; Yavandhassani, J. (2025). "Modeling of total ionizing dose (TID) effects on the nonuniform distribution of Si/SiO2 interface trap energy states in MOS devices". Scientific Reports. 15: 17082. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-01325-3. PMC 12084595.

- ^ ICRP 2007, paragraph 55.

- ^ Huether, Sue E.; McCance, Kathryn L. (2016-01-22). Understanding pathophysiology (6th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. p. 530. ISBN 9780323354097. OCLC 740632205.

- ^ a b "Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)". Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. 2015-02-26. Archived from the original on 2019-09-22. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)". Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b c ICRP 2007.

- ^ Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, Kollias N, Southall MD (2012). "Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes". J. Invest. Dermatol. 132 (7): 1901–1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476. PMID 22318388.

- ^ "Measuring Radiation". NRC Web. Archived from the original on 2025-05-16. Retrieved 2025-10-06.

- ^ Lewis, Leon; Caplan, Paul E (January 1, 1950). "The Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope as a Radiation Hazard". California Medicine. 72 (1): 26–30 [27]. PMC 1520288. PMID 15408494.

- ^ United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (2000). "Annex B". Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation. Vol. 1. United Nations. p. 121. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Mortazavi, S.M.J.; P.A. Karamb (2005). "Apparent lack of radiation susceptibility among residents of the high background radiation area in Ramsar, Iran: can we relax our standards?". Radioactivity in the Environment. 7: 1141–1147. doi:10.1016/S1569-4860(04)07140-2. ISBN 9780080441375. ISSN 1569-4860.

- ^ Sohrabi, Mehdi; Babapouran, Mozhgan (2005). "New public dose assessment from internal and external exposures in low- and elevated-level natural radiation areas of Ramsar, Iran". International Congress Series. 1276: 169–174. doi:10.1016/j.ics.2004.11.102.

- ^ "Health Risks". Radon. EPA. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2012-03-05.

- ^ Camphausen KA, Lawrence RC. "Principles of Radiation Therapy" Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- ^ Pattison JE, Bachmann DJ, Beddoe AH (1996). "Gamma Dosimetry at Surfaces of Cylindrical Containers". Journal of Radiological Protection. 16 (4): 249–261. Bibcode:1996JRP....16..249P. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/16/4/004. S2CID 71757795.

- ^ Pattison, J.E. (1999). "Finger Doses Received during Samarium-153 Injections". Health Physics. 77 (5): 530–5. doi:10.1097/00004032-199911000-00006. PMID 10524506.

- ^ "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. 21 March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Effective Dose Rate". NAIRAS (Nowcast of Atmospheric Ionizing Radiation System). Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jeffrey R. Davis; Robert Johnson; Jan Stepanek (2008). Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 221–230. ISBN 9780781774666. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2015-06-27 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "New Symbol Launched to Warn Public About Radiation Dangers". International Atomic Energy Agency. February 15, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-17.

Literature

[edit]- ICRP (2007). The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (Annals of the ICRP). ICRP publication 103. Vol. 37:2–4. ISBN 978-0-7020-3048-2. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

External links

[edit]- The Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulates most commercial radiation sources and non-medical exposures in the US:

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Ionizing Radiation

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation 2000 Report Volume 1: Sources, Volume 2: Effects

- Beginners Guide to Ionising Radiation Measurement

- Mike Hanley. "XrayRisk.com : Radiation Risk Calculator. Calculate Radiation Dose and Cancer Risk". (from CT scans and xrays).

- Free Radiation Safety Course Archived 2018-04-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Health Physics Society Public Education Website

- Oak Ridge Reservation Basic Radiation Facts

![2007 ISO radioactivity danger symbol intended for IAEA Category 1, 2 and 3 sources defined as dangerous sources capable of death or serious injury.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Logo_iso_radiation.svg/250px-Logo_iso_radiation.svg.png)