Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Metaphase

View on Wikipedia

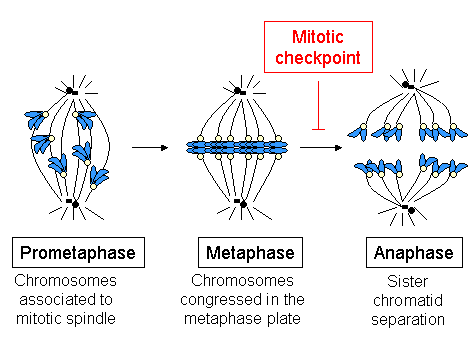

Metaphase (from Ancient Greek μετα- (meta-) beyond, above, transcending and from Ancient Greek φάσις (phásis) 'appearance') is a stage of mitosis in the cell cycle in which chromosomes of eukaryotes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase).[1] These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, align in the equator of the cell between the spindle poles at the metaphase plate, before being separated into each of the two daughter nuclei. This alignment marks the beginning of metaphase.[2] Metaphase accounts for approximately 4% of the cell cycle's duration.[citation needed]

In metaphase, microtubules from both duplicated centrosomes on opposite poles of the cell have completed attachment to kinetochores on condensed chromosomes. The centromeres of the chromosomes convene themselves on the metaphase plate, an imaginary line that is equidistant from the two spindle poles.[3] This even alignment is due to the counterbalance of the pulling powers generated by the opposing kinetochore microtubules,[4] analogous to a tug-of-war between two people of equal strength, ending with the destruction of B cyclin.[5]

In order to prevent deleterious nondisjunction events, a key cell cycle checkpoint, the spindle checkpoint, verifies this evenly balanced alignment and ensures that every kinetochore is properly attached to a bundle of microtubules and is under balanced bipolar tension. Sister chromatids require active separase to hydrolyze the cohesin that bind them together prior to progression to anaphase. Any unattached or improperly attached kinetochores generate signals that prevent the activation of the anaphase promoting complex (cyclosome or APC/C), a ubiquitin ligase which targets securin and cyclin B for degradation via the proteosome. As long as securin and cyclin B remain active, separase remains inactive, preventing premature progression to anaphase.

Metaphase in cytogenetics and cancer studies

[edit]

The analysis of metaphase chromosomes is one of the main tools of classical cytogenetics and cancer studies. Chromosomes are condensed (thickened) and highly coiled in metaphase, which makes them most suitable for visual analysis. Metaphase chromosomes make the classical picture of chromosomes (karyotype). For classical cytogenetic analyses, cells are grown in short term culture and arrested in metaphase using mitotic inhibitor. Further they are used for slide preparation and banding (staining) of chromosomes to be visualised under microscope to study structure and number of chromosomes (karyotype). Staining of the slides, often with Giemsa (G banding) or Quinacrine, produces a pattern of in total up to several hundred bands. Normal metaphase spreads are used in methods like FISH and as a hybridization matrix for comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) experiments.

Malignant cells from solid tumors or leukemia samples can also be used for cytogenetic analysis to generate metaphase preparations. Inspection of the stained metaphase chromosomes allows the determination of numerical and structural changes in the tumor cell genome, for example, losses of chromosomal segments or translocations, which may lead to chimeric oncogenes, such as bcr-abl in chronic myelogenous leukemia.

References

[edit]- ^ "Chromosome condensation through mitosis". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Hopkin, Karen; Johnson, Alexander; Morgan, David; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2019). Essential cell biology (Fifth ed.). New York London: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 632–633. ISBN 9780393680393.

- ^ "Metaphase plate". Biology Dictionary. Biology Online. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Metaphase". Nature Education. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "The Cell Cycle". Kimball's Biology Pages. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

External links

[edit] Media related to Metaphase at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Metaphase at Wikimedia Commons