Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

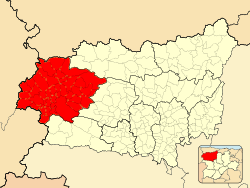

El Bierzo

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

El Bierzo (Spanish pronunciation: [el ˈβjeɾ.θo]; Leonese: El Bierciu or El Bierzu[1] ) is a comarca in the province of León, Spain. Its capital is the town of Ponferrada. Other major towns are Bembibre and Villafranca del Bierzo, the historical capital.

The territory of El Bierzo includes most of the upper basin of the Sil river. It is surrounded by mountains on all sides, which makes this area remarkably isolated from all neighbouring lands.

History

[edit]In pre-Roman times the region was populated by the Astures, a Hispano-Celtic Gallaecian people. They were conquered by Emperor Augustus in the Astur-Cantabrian Wars (29–19 BC), and the area quickly became the largest mining center of the Empire during the Roman period, where gold and other metals and minerals were extracted. Numerous Roman mining sites are still visible in the area, one of the most spectacular being Las Médulas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997.[2] Romans also imported grapevines, and wine production thrived in the region until the propagation of Phylloxera at the end of the 19th century, which destroyed the majority of the vineyards.

In the early Middle Ages, El Bierzo became part of the Kingdom of León. The region saw the establishment of several monasteries, including Santa María de Carracedo and San Pedro de Montes, which played a role in its religious and cultural development. Mozarabic art also flourished in the area, with Santiago de Peñalba standing as a notable example. This church, constructed in the 10th century, is an important representation of Mozarabic architecture and reflects the artistic influences of the time. Fortifications such as the Templar Castle of Ponferrada were also constructed during the Middle Ages, reflecting its strategic importance.

The Camino de Santiago passes through El Bierzo, significantly shaping its historical and cultural landscape. This medieval pilgrimage route brought travelers and religious influence to the region, fostering the development of Romanesque architecture. Notable examples include the Church of Santiago in Villafranca del Bierzo and other ecclesiastical structures that served the needs of pilgrims.

In the 19th century, El Bierzo was briefly a province of its own within the larger Leonese region from 1821 to 1823, with the new administrative division of Spain in 1833 the majority of the region was integrated in the province of León,[3] with the Valdeorras municipalities becoming part of Galicia. The 19th and 20th centuries were marked by industrial developments, with mining and energy production becoming central to the local economy.

El Bierzo developed its own peculiarities as Galician and Leonese traditions mixed under Castilian influence, and thus was granted the administrative status of comarca. Spanish is the official language, but local dialects of Galician and Leonese are also spoken in the westernmost areas and are present in some village toponyms. In the 12th century there was a colony of immigrants from Poitou in the Bierzo.[4]

The status of El Bierzo as a shire is recognized by law, and it is the only one officially recognized in the autonomous community of Castile and León.

Languages

[edit]The predominant language nowadays is Spanish but the local vernaculars can be classified as either Galician or Leonese; the Galician traits increase as one moves from east to west. The use of Galician and Leonese in everyday speech has mixed usages. Although both have enjoyed a recent revival through the work of different associations that promote their use and study, Galician has been more favored, extending its area of influence. Leonese continues to have a very limited use.

The Galician language, in addition to Galicia, is also spoken in western El Bierzo and a small area called As Portelas in the westernmost part of the province of Zamora, both areas in the community of Castile and Leon; the teaching of Galician in public education is allowed in those areas under an agreement between the Education Departments of Galicia and Castile and Leon.[5] In 2005–2006 there were 844 students studying in 9 municipalities of El Bierzo, with 47 teachers, and in 2008–2009 more than 1000 students enrolled in Galician courses in El Bierzo and As Portelas, although many of them are children of immigrants from Galicia. [citation needed] In addition to that, the Statute of Autonomy of Castile and Leon, in its article No. 5, states: "[We] Shall respect and protect the Galician language and language patterns in places where the language is habitually used.". The number of Galician speakers in El Bierzo is estimated to be about 35,000 people concentrated in the westernmost municipalities of the region. In the last year the Bercianos [clarification needed] have made many campaigns to improve Galicians' use in their Comarca, even with the collaboration of members from the Royal Galician Academy, professors and students from Villafranca del Bierzo.[6] Politically, usually the Galeguist parties defend the use of Galician language in the western Bierzo, parties as Galician Nationalist Bloc or PSdeG, but recently, even right-wing parties like People's Party defend the Galician language in the area.

Pachuezu or patsuezu is the western Asturleonese variant most entrenched in the north of El Bierzo, where there are estimated to be about 4,000 speakers of Leonese.

Economy

[edit]The railroad arrived in the region in 1881, and during World War I local tungsten deposits were exploited to supply the arms industry. In 1918 the Ponferrada Mining, Iron and Steel Company (Spanish: Minero Siderúrgica de Ponferrada (MSP)) was founded to exploit coal deposits in the region, and it grew to become Spain's largest coal mining corporation. The Spanish National Energy Corporation (Endesa) was founded in 1944 and in 1949 it opened Spain's first coal-fueled power plant in Ponferrada, Compostilla I. In 1960 the Bárcena Dam (Spanish: Pantano de Bárcena) opened and by the second half of the 20th century the economy of the region was mainly based on mining and electricity generation, both hydroelectric and coal-fueled.

Starting in the late 1980s most mines were closed, and after the collapse of the mining industry the region was for a while in a crisis. However, in the late 1990s the region underwent a major transformation with the establishment of several industrial and services firms, the reintroduction of commercial wine production, the opening of a local branch of the University of León in Ponferrada offering several undergraduate degrees, and in general a radical improvement of the region's infrastructure. The economy is now based mainly on tourism, agriculture (fruit and wine), wind power generation and slate mining.

Important factors contributing to the recent boom of the tourism industry in the region are the increasing popularity of the Way of St. James (Spanish: Camino de Santiago; a pilgrimage route that goes from France to Santiago de Compostela, Galicia), the designation in 1997 of Las Médulas as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the development of rural tourism lodging and wineries in the area. The Energy City Foundation Spanish: Fundación Ciudad de la Energía was established in Ponferrada in 2006 and is currently overseeing the construction of the National Energy Museum (Spanish: Museo Nacional de la Energía) in the city, as well as sponsoring several other initiatives that should further boost tourism and the economy of the region.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alvar López, Manuel (1999). Atlas lingüístico de Castilla y León [Linguistic Atlas of Castile and León]. Junta de Castilla y León. ISBN 84-7846-856-0.

- ^ a b "La Fundación Las Médulas dará a conocer la riqueza arqueológica de la zona con un portal en Internet". Archived from the original on 2004-10-15. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "El Bierzo en la Historia" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Richard A. Fletcher (1978) The Episcopate in the Kingdom of León in the Twelfth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 49.

- ^ "Castilla y León". Xunta de Galicia. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Galiza, Sermos (12 June 2015). "Carta dun alumno que quere estudar galego". Sermos Galiza (in Galician). Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

External links

[edit]- El Bierzo Regional Council Official Website (in Spanish)

- Consejo Regulador de la Denominación de Origen Bierzo (in Spanish)

- Instituto de Estudios Bercianos (in Spanish)

El Bierzo

View on GrokipediaEl Bierzo is a comarca in the northwest of León province, within the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain, covering an area of 2,954.28 km² that constitutes 18% of the province's territory.[1] Its capital is Ponferrada, the region's largest municipality.[2] Characterized by mountainous terrain drained by the Sil River, the area features diverse landscapes including slate soils conducive to viticulture and remnants of extensive Roman-era exploitation.[3]

Historically, El Bierzo gained prominence through Roman gold mining, most notably at Las Médulas, the ancient empire's largest open-pit operation, which dramatically altered the local topography through hydraulic techniques and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997 for its cultural landscape.[4] The region later developed a coal mining industry in the 19th and 20th centuries, which became central to its economy but has since declined, prompting shifts toward renewable energy, agriculture, and tourism.[2] Key economic sectors now include the production of Bierzo Denominación de Origen wines from indigenous Mencía grapes, chestnut cultivation yielding significant annual output, and visitor attractions along the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route, which passes through Ponferrada and Villafranca del Bierzo.[1][5][6] The comarca maintains a distinct identity, recognized in regional statutes, with traditional architecture, rural villages, and natural monuments preserving its heritage amid ongoing reindustrialization efforts.[7][8]

Geography

Location and Administrative Status

El Bierzo constitutes a comarca situated in the northwestern extremity of León province, within the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain, with Ponferrada serving as its capital and largest municipality.[9] This administrative division encompasses 38 municipalities and spans approximately 3,178 km², representing a significant portion of western León.[10] Geographically, El Bierzo is delimited to the west by the Galician provinces of Lugo and Ourense, to the north by the Principality of Asturias, and to the east and south by other territories within León province, forming a transitional zone between the Castilian plateau and the Atlantic-influenced northwest.[1] The comarca falls under the European Union's Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) as part of the León NUTS 3 region (ES413), facilitating eligibility for regional development funding and statistical aggregation.[11] Legally recognized as a local government entity under Ley 1/1991 of 14 March, El Bierzo operates as a comarca with the Consejo Comarcal del Bierzo providing coordinated administration across its municipalities for services such as planning, infrastructure, and economic development, distinct from provincial or autonomous community governance.[9] [12] This structure enables localized decision-making while remaining integrated into León's provincial framework.[13]Topography and Natural Features

El Bierzo encompasses a topographic depression in the western León province, dominated by the upper basin of the Sil River, which carves a broad valley enclosed by encircling mountain ranges that rise to elevations exceeding 2,000 meters.[14] To the south lie the Montes de León, including the Montes Aquilianos subrange, while northern limits feature sierras such as the Caurel and Gistredo, creating a basin-like structure with steep gradients transitioning to gentler alluvial plains along the river.[14] The eastern sector showcases the Las Médulas badlands, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1997, where hydraulic erosion has sculpted auriferous quartzite into pyramid-shaped hills and deep ravines, exemplifying the transformative effects of water-driven geological processes on bedrock stability.[4] This site's formation stems from the ruina montium method, involving aqueduct-fed galleries that released pressurized water to destabilize and collapse overburden, yielding a lunar-like terrain of collapsed montes amid residual peaks up to 130 meters high.[4][15] Underlying geology consists primarily of Paleozoic schists and slates, interspersed with mineral veins that underpin the region's ferruginous soils and support diverse geomorphic features from slate terraces to schist-derived slopes.[16] Las Médulas was designated a Natural Monument in 2002, recognizing its unique erosional landforms and ecological recovery.[4]Climate and Environmental Conditions

El Bierzo features a transitional climate influenced by Mediterranean, continental, and Atlantic patterns, resulting in mild winters with average temperatures of 5-10°C and warm summers reaching 20-25°C. The annual mean temperature stands at 12.3°C, with winter lows around 3.6°C and occasional summer peaks up to 28°C.[17][18] Precipitation averages 721-730 mm annually, predominantly falling in autumn and winter, with November recording up to 105 mm on average and July the driest at 31 mm.[17][19] Topographic variations create distinct microclimates: lower valleys benefit from warmer conditions and elevated humidity due to fog and proximity to the Sil River, while higher elevations in the surrounding mountains experience cooler temperatures and increased precipitation, sometimes exceeding 1,000 mm in upland areas like the Courel massif. These factors, including persistent morning mists, contribute to favorable conditions for local agriculture, particularly grape cultivation, by moderating temperature extremes and retaining soil moisture.[20][21][22] Records from AEMET stations in Ponferrada and Villafranca del Bierzo document a rise in drought frequency since 2000, with extended dry spells in summer months aligning with peninsula-wide reductions in precipitation variability, though annual totals remain stable relative to historical norms without evidence of systemic aridification unique to the region.[23][24]History

Ancient and Roman Periods

Prior to Roman arrival, the region of El Bierzo was inhabited by the Astures, a Hispano-Celtic tribal confederation occupying northwest Hispania, including fortified hill settlements known as castros. These structures, dating from the 8th century BCE through the 1st century BCE, featured circular dwellings and defensive walls, reflecting a semi-nomadic pastoral economy with influences from broader Celtic and local Iberian traditions. Archaeological evidence from sites like Bérgida in Cacabelos indicates Astur presence, with artifacts housed in local museums underscoring pre-Roman cultural continuity in the area.[25][26] Roman forces under Augustus completed the conquest of Astur and Cantabrian territories between 29 and 19 BCE, incorporating El Bierzo into the province of Hispania Tarraconensis. This subjugation enabled systematic exploitation of the region's gold deposits, particularly at Las Médulas, where mining commenced in the early 1st century CE and persisted until the late 2nd or early 3rd century CE. Employing ruina montium—a hydraulic technique involving tunnels and channeled water to collapse mountains—the Romans extracted gold on an industrial scale, processing vast quartz veins and alluvial deposits through water-powered erosion. This method drastically altered the topography, eroding approximately 220 million cubic meters of material and creating the distinctive badlands visible today, with output estimated at several tons of gold, contributing significantly to imperial finances.[4] To support operations, Romans constructed extensive infrastructure, including aqueducts spanning over 100 kilometers for water diversion and roads facilitating transport from mines to coastal ports. Villas and auxiliary settlements emerged around mining centers, integrating local labor—often coerced Astures—into the extractive economy, though evidence of villas specific to El Bierzo remains sparse compared to agricultural heartlands elsewhere in Tarraconensis. The mining boom underscored Rome's resource-driven colonization, prioritizing economic yield over landscape preservation, with hydraulic engineering feats exemplifying imperial technological prowess.[27][28]Medieval and Early Modern Era

Following the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century, El Bierzo served as a frontier zone in the Kingdom of Asturias and later León, experiencing periodic raids such as the incursion directed toward the region in 791.[29] The area faced depopulation pressures amid these conflicts, prompting repopulation initiatives under Asturian-Leonese monarchs from the mid-9th century onward, with intensified efforts in the 10th century focused on agrarian reorganization and monastic foundations.[30] These efforts drew on the region's eremitic heritage, exemplified by 7th-century figures like San Fructuoso, and saw bishops such as Genadio of Astorga promoting hermitages and small communities in the 10th century, forming the "Tebaida berciana" network of ascetic settlements that facilitated territorial consolidation.[31] By the 11th and 12th centuries, feudal structures solidified, with monasteries and lay lords managing estates amid the growing pilgrimage traffic on the Camino de Santiago's French Way. In 1178, King Ferdinand II of León granted Ponferrada to the Knights Templar, who constructed the castle there to safeguard pilgrims crossing the iron bridge and navigating the route's vulnerabilities. Villafranca del Bierzo developed as a key halting point for French pilgrims, earning its name and featuring the Romanesque Puerta del Perdón at the Iglesia de Santiago, which medieval tradition allowed to confer partial indulgences on those too ill to reach Compostela.[32] Charters and chronicles document these developments, underscoring the Templars' and monastic orders' roles in defensive infrastructure and economic oversight, including tolls and land grants that bolstered regional stability. In the early modern era under Habsburg administration, El Bierzo remained integrated into the province of León within the Crown of Castile, governed through local corregidores and reliant on feudal tenures evolving into seigneurial jurisdictions. The economy emphasized subsistence agriculture—cultivating cereals, vines, and olives—supplemented by small-scale iron forges exploiting local ore deposits, though output remained limited, with estimates of under 500 quintales annually in the 16th and 17th centuries before modest expansions.[33] This agrarian-ironworking base supported population recovery but faced constraints from poor transport and periodic crises, maintaining the region's peripheral status relative to central Castilian hubs.[33]Industrialization and 19th-20th Century Developments

The industrialization of El Bierzo accelerated in the late 19th century, driven primarily by the exploitation of coal deposits that had been identified earlier during infrastructure projects such as road construction in the Bembibre area in the 18th century. Systematic mining operations commenced around the mid-to-late 1800s, particularly in areas like Fabero, where concessions were documented in official provincial bulletins, aligning with broader Spanish efforts to harness domestic energy resources amid rising industrial demands for steam power and metallurgy. These developments contributed to the region's integration into national economic networks, though profitability remained limited until technological advancements in extraction and transportation improved yields. Iron mining, longstanding in the area, also saw renewed activity, supporting local siderurgical ventures like the Minero Siderúrgica de Ponferrada, established to consolidate dispersed concessions for both coal and ore processing.[34][35][36] In the early 20th century, infrastructure investments facilitated mining expansion, exemplified by the Ponferrada-Villablino railway line, authorized by parliamentary bill on July 24, 1918, and operational by 1919 as a metre-gauge route spanning 64 km to transport coal from inland pits to processing and power facilities. This connectivity reduced transport costs and enabled market-responsive scaling, with output fluctuating based on demand from Spain's growing energy sector and technological shifts like mechanized drilling. Labor inflows from neighboring Galicia and Asturias bolstered workforce growth, concentrating migrants in mining hubs such as Villablino and fostering tight-knit communities oriented around pit operations.[37][38] Union organization emerged concurrently, with the Sindicato Minero Castellano affiliated to the UGT expanding in El Bierzo by the 1920s, channeling worker grievances over wages and safety amid volatile production cycles tied to global coal prices and domestic policy. Peak activity occurred during the mid-20th century's developmental phases, when enhanced mechanization and state incentives under autarkic policies drove significant output surges, though exact regional figures varied with basin-specific geology and market integration. These booms reflected causal dependencies on external factors like railway efficiency and fuel substitution technologies, underscoring El Bierzo's role as a peripheral yet vital node in Spain's coal-dependent industrialization.[39][40][41]Spanish Civil War and Franco Era

At the onset of the Spanish Civil War on July 17, 1936, El Bierzo's mining communities, particularly around Ponferrada, mounted initial resistance to the military uprising, with local militias formed by workers opposing the coup. However, Nationalist forces advancing from Galicia under Comandante Jesús Manso, supported by local Falangists, captured Ponferrada on July 21, 1936, securing rapid control of the region despite sporadic clashes in areas like Fuentesnuevas where Republican sympathizers clashed with advancing troops.[42][43] The area's industrial workforce, predominantly aligned with Republican unions, contributed to brief but fierce local divisions, though the Nationalist advance overwhelmed defenses within days.[44] Following the Nationalist victory in 1939, systematic repression targeted perceived Republican loyalists, including miners and left-leaning civilians, through extrajudicial "paseos," summary trials, and executions. Estimates indicate approximately 3,000 individuals were repressed across El Bierzo, with over 1,120 violent deaths recorded in Ponferrada alone from 1936 to 1951, many involving executions and burials in mass graves such as Montearenas.[45] These figures, drawn from victim associations and local archival efforts, reflect the regime's purge of political opponents, though exact counts vary due to incomplete records and ongoing exhumations. Recent commemorations, including plaques erected in Ponferrada during the 2020s, mark sites of these killings to preserve survivor testimonies and archaeological findings.[46] During the Franco era (1939–1975), the regime emphasized coal mining expansion in El Bierzo as a strategic economic priority, nationalizing operations under state syndicates to fuel autarkic industrialization. This involved forced labor through batallones de trabajadores, where political prisoners were compelled to extract coal in camps like Fabero, enduring harsh conditions including malnutrition and extended shifts without pay, as documented in prisoner accounts and labor records.[47][48] Such practices, affecting hundreds in the region, blended punitive repression with resource mobilization, contributing to output growth—Bierzo's production rose from under 1 million tons annually pre-war to peaks exceeding 3 million by the 1950s—while suppressing labor dissent.[49]Post-Franco Transition and Recent Events

Spain's transition from the Franco dictatorship to democracy, following his death on November 20, 1975, led to the approval of the 1978 Constitution, which devolved powers to autonomous communities while maintaining provincial structures. El Bierzo, embedded within León province, was thus bound to the emerging Autonomous Community of Castilla y León, formalized by its Statute of Autonomy approved in 1981 and reformed in 1983 and 2007, despite persistent local Biercista movements advocating for distinct regional status or secession from León.[50][51] To address these regionalist demands without altering broader administrative ties, the Cortes of Castilla y León enacted Ley 1/1991 on March 14, 1991, establishing the Comarca de El Bierzo as a local entity with its own Consejo Comarcal, comprising 51 councilors from 51 municipalities and endowed with competencies in areas like rural development, tourism promotion, and environmental management.[9][52] The body was formally constituted on July 11, 1991, providing a mechanism for coordinated local governance that has endured, albeit with ongoing debates over its fiscal autonomy and efficacy in representing Bierzo's interests against provincial dominance.[53] Spain's entry into the European Economic Community on January 1, 1986, exposed El Bierzo's coal-dependent economy to supranational competition and environmental directives, hastening the rationalization of mining operations through subsidy reductions and stricter regulations under emerging EU coal and steel community policies.[54] These pressures contributed to early closures and restructuring, setting the stage for broader decarbonization efforts that tested local institutional resilience. In the 2010s, the push for EU-aligned decarbonization culminated in a 2018 national agreement between the government, unions, and industry to shutter all uneconomical coal mines by December 31, 2018, backed by €250 million in transitional funding for retraining, infrastructure, and diversification in hard-hit zones including El Bierzo.[55] The subsequent 2019 Just Transition Strategy, coordinated via the Instituto para la Transición Justa, allocated resources to León's mining comarcas, yet empirical outcomes have sparked contention: while coal's electricity share plummeted from 14.3% in 2018 to near zero by 2022, local stakeholders have criticized the funds' distribution for failing to fully mitigate job losses or stabilize demographics, with phase-out accelerating under Spain's 2030 coal power ban pledge.[56][57]Government and Politics

Local Administration and Institutions

The local administration of El Bierzo operates within a hierarchical framework, where 38 municipalities serve as the foundational units, coordinated by the Consejo Comarcal del Bierzo and subject to oversight from the Diputación Provincial de León and the Junta de Castilla y León.[13] [12] [58] The Consejo Comarcal, created by Ley 1/1991 of March 14, is led by a president and a Pleno composed of 27 consejeros elected indirectly every four years by municipal delegates from six geographic zones, with representation allocated proportionally to each area's population.[9] [59] [60] Delegated competencies from the Diputación include technical and legal assistance to municipalities, tourism promotion via the Patronato de Turismo del Bierzo, coordination of waste collection services across smaller localities, and support for cultural initiatives such as the annual Jornadas Gastronómicas.[9] [61] [62] [13] Fiscal resources derive mainly from provincial transfers, with the 2025 budget totaling 8.4 million euros, incorporating 2.87 million euros for biennial small infrastructure works and 1.59 million euros for support to neighborhood councils (juntas vecinales).[63] [64] [65] Since the early 2020s, administrative modernization efforts have emphasized digital tools, including the Oficina Virtual platform for electronic procedures and the digitization of administrative records to improve efficiency in rural areas.[13]Regional Identity and Autonomy Aspirations

El Bierzo's regional identity is rooted in its distinct geographical isolation, historical precedents as a separate administrative unit during the 19th-century intendencia, and cultural affinities with Galicia, including the use of the galego-berciano dialect in its western areas, which differs from central Leonese speech patterns.[66] These elements foster a sense of uniqueness, often contrasted with the perceived dominance of León's provincial institutions, leading to claims of cultural dilution and inequitable resource distribution. Proponents argue that this identity justifies enhanced self-governance to preserve local traditions and address specific needs unmet by broader provincial oversight.[67] Autonomy aspirations gained momentum in the 1980s amid Spain's regional devolution, culminating in the Ley 1/1991 of March 14, which established El Bierzo as Spain's first comarca with legal personality, territorial demarcation, and functional autonomy within Castile and León, following sustained local campaigns for recognition beyond mere municipal aggregation.[9] Despite this, demands escalated in the 1990s and 2000s for provincial status, driven by tensions over funding and infrastructure priorities favoring León city, with regionalist groups like the precursor to the Coalition for El Bierzo advocating separation to enable direct access to state transfers and policy tailored to the comarca's mining heritage and rural challenges. Polls reflect divided but notable support: a 2020 Electomanía survey found 75% of residents favoring provincial status, roughly split among integration as a province in a Leonese autonomy (about 30%), annexation to Galicia (about 25%), or independent provincial elevation, though the remainder preferred maintaining comarca status within León.[68] More recent 2024-2025 surveys indicate a plurality preferring Bierzo as a province within a hypothetical uniprovincial Leonese autonomy over full detachment or Galician merger, with support hovering around 40-50% for enhanced self-rule options amid broader Leonese separatist sentiments.[69][70] Critics of further autonomy, including some local economists and integrated provincial advocates, contend that fragmentation risks administrative duplication and reduced economies of scale, citing examples from other Spanish comarcas where devolved powers led to higher per-capita costs without proportional service improvements; they attribute Bierzo's stagnation more to national-level industrial policy failures, such as abrupt mine closures post-2018, than to provincial integration, which has facilitated shared infrastructure like rail links to León.[71] No binding referendums have occurred, and formal secession remains absent, with the Coalition for El Bierzo—formed in 2015—securing local electoral gains but limited provincial influence, underscoring that while identity-driven aspirations persist, pragmatic integration benefits and fiscal constraints temper pushes for full provincial independence. Empirical data from identity surveys show only marginal standalone support for Bierzo-specific autonomy outside Leonese contexts (around 2-5% in broader Leonese samples), suggesting causal factors like depopulation and economic transition outweigh separatist momentum.[72]Demographics

Population Distribution and Trends

El Bierzo's population stood at 119,186 residents as of January 1, 2023, distributed across 38 municipalities spanning urban centers and dispersed rural settlements.[73] Ponferrada, the largest hub, accounted for 62,941 inhabitants, representing over half the comarca's total, followed by Bembibre with 8,196 and Villafranca del Bierzo with 2,649.[73][73] Rural areas feature numerous small nuclei, with 17 municipalities historically under 1,000 residents, underscoring a pronounced urban-rural divide where smaller peripheral locales hold minimal shares of the overall populace.[74] Census data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) indicate ongoing decline, with a net loss of 795 inhabitants in 2023 alone, reducing the total from 119,827 in 2022.[73] Core urban areas like Ponferrada have shown relative stability or slower erosion compared to peripheral zones, where depopulation rates exceed annual averages; for instance, aggregate losses reflect steadier figures in the capital versus sharper drops in outlying municipalities.[75] Post-1950s patterns reveal increasing urban concentration, with larger hubs absorbing proportional growth amid broader dispersal into fewer viable rural entities.[76] The demographic profile exhibits advanced aging, with a median age approximating 48 years regionally, mirroring Castilla y León's 48.24-year average, and Ponferrada's mediana at 49.08 years.[77][78] Fertility remains critically low, registering only 469 births in 2023 against a population base yielding a crude rate below 4 per 1,000, while the provincial indicator hovers near 1.06 children per woman, well under replacement levels.[79][80] This structure amplifies urban-rural disparities, as core areas retain younger cohorts relative to aging rural peripheries per INE granular breakdowns.[81]Migration and Depopulation Dynamics

During the mid-20th century, El Bierzo saw substantial internal migration inflows driven by the expansion of coal mining, which attracted workers from rural areas of León, Galicia, and other parts of Spain, contributing to a regional population peak of approximately 250,000 inhabitants in the 1960s.[82] This growth was tied to industrial employment opportunities in the coal basins around Ponferrada and Bembibre, where mining operations peaked amid Spain's post-war economic development under the Franco regime.[83] Following the decline of the coal sector after the 1980s, marked by mine closures and restructuring under European Union energy policies, El Bierzo experienced accelerated outmigration, particularly of younger residents seeking jobs in urban centers such as Madrid and Bilbao's industrial zones.[84][85] This resulted in net population losses, with the region registering a decline of over 40,000 residents between 2000 and 2020 amid broader provincial trends in León, where annual losses reached thousands by the 2010s.[86] Youth emigration intensified post-2008 financial crisis, correlating directly with employment drops in extractive industries, where unemployment rates in mining-dependent municipalities exceeded 20% in affected years.[83] In the 2020s, limited return migration has emerged, supported by expanded telecommuting options post-COVID-19 and familial ties across the Galician border, facilitating cross-regional movements for those retaining remote jobs in larger cities.[87] However, net outflows persist, with recent INE data showing annual losses of around 600-700 inhabitants, underscoring that depopulation dynamics remain primarily causal to persistent structural unemployment rather than voluntary lifestyle shifts.[88][83]Economy

Traditional Industries: Mining and Resource Extraction

Mining in El Bierzo traces its origins to Roman exploitation of gold deposits, particularly at Las Médulas, which represented the largest open-pit gold mine in the Roman Empire through hydraulic techniques known as ruina montium, involving the diversion of water to erode mountainsides and extract ore.[89] Estimates based on sterile tailings and waste deposits indicate that Las Médulas accounted for nearly 15% of Roman gold production.[90] The region's iron ore extraction centered on the Laciana-Bierzo fields, where deposits in areas like the Wagner mineral district supported early industrial development alongside coal resources in the adjacent Río Sil basin.[91] Coal mining dominated later traditional industries, with basins in the Sil and La Silva valleys employing underground methods to access Carboniferous seams dating from the Upper Namurian to Stephanian periods.[92] Intensive exploration and extraction in these areas occurred from the mid-20th century onward, contributing to the local economy through bituminous and anthracitic coals.[93]Agricultural Sector and Wine Production

The Denominación de Origen Protegida (DOP) Bierzo, established on November 11, 1989, oversees viticulture across roughly 2,400 hectares of inscribed vineyards, primarily on steep slate slopes that retain moisture and confer mineral notes to the wines.[94][95] Regulations limit yields to promote quality, with Mencía dominating red wine production at approximately two-thirds of the total area, yielding structured, acidic reds, while Godello whites, often from old vines, represent a smaller but growing share noted for their citrus and stone fruit profiles.[3][96] Annual wine output has stabilized around 8-9 million bottles, with harvest data from 2024 recording 7,978,655 kilograms of grapes, reflecting consistent quality amid variable weather.[95][97] Exports have expanded notably in the 2020s, comprising up to one-third of production and targeting international markets, though small-scale operations—many producing under 400,000 bottles annually—grapple with parcel fragmentation, high costs, and consolidation pressures from larger estates.[98][99] Complementing viticulture, El Bierzo sustains polyculture on minifundist smallholdings, where chestnuts (protected under IGP Castaña de El Bierzo) form a staple crop harvested in autumn for local and export markets, alongside PGI-designated roasted peppers (Pimiento Asado del Bierzo) prized for their sweet flavor from the region's microclimate, and kiwis cultivated in fertile valleys.[100][101] These diverse outputs buffer economic risks for fragmented farms, though yields remain modest due to terrain constraints and competition from industrialized agriculture elsewhere.[102]Shift to Tourism and Services

Tourism has positioned itself as a vital economic diversifier in El Bierzo, drawing over 500,000 visitors annually and yielding more than 30 million euros in yearly revenue, primarily through accommodations, dining, and local expenditures. In 2023, the sector generated 14.5 million euros, increasing to 22.5 million euros in 2024, with an average visitor stay of 1.4 days and daily spending around 60 euros per person.[103] This influx, largely motivated by the region's cultural and natural heritage, has spurred job creation in hospitality and ancillary services, contributing to the broader service economy that now holds a growing relative weight amid industrial decline.[83] In Ponferrada, the administrative hub, the service sector accounts for 68.2% of employment, marking a transition from extractive industries, though this share ranks among Spain's lower figures nationally. Retail expansion and educational services have underpinned this shift, with the Universidad de León's Ponferrada campus supporting nearly 1,000 students and delivering over 10 million euros in direct annual economic impact through student spending, faculty activities, and events.[104][105] Despite these advances, tourism's role remains constrained by seasonality, with visitor peaks concentrated in warmer months—evident in Ponferrada's 2025 data showing accelerated growth in September over prior periods—leading to temporary positions that fail to match the wage stability and levels of legacy mining roles.[106] This structural limitation tempers the sector's capacity to fully supplant industrial contributions, necessitating complementary strategies for sustainable diversification.Energy Transition Challenges

The closure of coal mines in El Bierzo, accelerated by the European Union's Emissions Trading System (ETS) which imposed rising carbon costs on uncompetitive operations, culminated in 2018 with the shutdown of most underground and opencast facilities under a national agreement to end state subsidies by December 31 of that year.[107] [108] This process directly eliminated around 2,000 mining jobs in the region, with an estimated 5,000 additional indirect positions lost in supply chains, transport, and related services, exacerbating economic dependence on a single industry that had sustained local communities for decades.[57] The EU's framework, while aimed at decarbonization, prioritized emissions reductions over localized socioeconomic safeguards, leaving gaps in immediate support mechanisms. In response, Spain's 2019 Just Transition Strategy, integrated into the broader Strategic Energy and Climate Framework, allocated approximately €250 million specifically for coal-dependent areas like El Bierzo to fund renewable energy projects, vocational retraining, and infrastructure diversification, with additional European funds channeled through the Recovery and Resilience Plan.[109] However, by 2023, unemployment in former mining municipalities exceeded 15%, far above regional averages, as retraining programs saw uptake rates below 30% due to mismatches in skills required for solar and wind sectors versus mining expertise. Renewables development, while advancing—such as solar installations in repurposed sites—has generated fewer and often lower-wage jobs than lost, with projections indicating only thousands regionally against prior tens of thousands economy-wide in fossil activities.[57] These dynamics have causally accelerated depopulation, as evidenced by heightened out-migration from stagnant mining valleys like Laciana adjacent to El Bierzo, where young workers cite persistent job scarcity and inadequate transition support as drivers of relocation to urban centers.[110] Government reports emphasize structural reforms, yet empirical shortfalls in job equivalence and local buy-in highlight the strategy's limitations, with official metrics potentially understating long-term displacement costs given the opacity of indirect effects in state evaluations.[111]Culture and Society

Languages and Linguistic Heritage

Castilian Spanish serves as the predominant and official language throughout El Bierzo, used in administration, education, and daily communication by the vast majority of the population.[112] In rural interior areas, minority use persists of Leonese dialects, collectively part of the Astur-Leonese linguistic continuum, with local variants known as bierzano featuring phonetic and lexical traits distinct from standard Leonese, such as simplified vowel systems and archaic verb forms.[113] Estimates for active Leonese speakers across the broader León province, including El Bierzo, range from 20,000 to 50,000, primarily among older rural residents, representing a small fraction of the comarca's approximately 80,000 inhabitants.[112] The western zones of El Bierzo exhibit transitional dialects blending Leonese with Galician elements, including metaphonic vowel shifts and shared vocabulary related to agriculture and terrain, reflecting historical cross-border exchanges with Galicia.[114] Here, Galician comprehension and usage are more robust, with around 30,000 speakers reported, constituting roughly 40% of the local population in those municipalities, though concentrated among the elderly and declining due to urbanization.[114] Overall Leonese and transitional varieties have receded sharply since the early 20th century, driven by mandatory Castilian-medium schooling under Franco-era policies, rural depopulation, and media dominance, reducing intergenerational transmission.[112] UNESCO classifies Astur-Leonese, encompassing bierzano forms, as "definitely endangered," citing intergenerational discontinuity and limited institutional support.[115] Preservation initiatives include academic documentation of oral traditions and dialectal corpora by groups like the Instituto Leonés de Cultura, which organizes events on Bierzo folklore and supports Leonese-language materials in schools, alongside sporadic local advocacy for co-official recognition.[116] These efforts, however, remain fragmented, with no widespread bilingual public signage in Leonese even in key towns like Ponferrada, where Castilian prevails exclusively in official contexts.Customs, Festivals, and Social Structures

The Magosto festival, celebrating the chestnut harvest, takes place annually in late October or early November in localities such as Santa Marina del Sil, involving communal roasting of chestnuts over open fires and gatherings that honor agrarian traditions dating back centuries.[117] This event underscores El Bierzo's historical reliance on chestnut cultivation in its mountainous terrain, with participants sharing roasted nuts and local wines in a ritual tied to the autumn equinox and pre-Christian harvest customs adapted to Christian calendars.[117] Holy Week, or Semana Santa, features prominent processions in Ponferrada, organized by longstanding cofradías such as the Real Hermandad de Jesús Nazareno, which conducts early morning runs by "corredores" in black tunics on Good Friday, followed by major parades like the Procesión de la Dolorosa and the Encuentro procession depicting the meeting of Christ and the Virgin Mary.[118] These events, spanning Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday with up to fifteen processions in 2025, draw on Baroque-era devotional practices and involve thousands in penitential marches through the historic center, emphasizing communal piety and historical continuity since at least the 17th century.[119] Similar brotherhoods operate in surrounding areas, including the Cofradía de la Soledad in Camponaraya and cofradías in Villafranca del Bierzo, maintaining rituals of silence, candlelit vigils, and sculpted pasos carried by members.[120] Templar-themed reenactments occur during Ponferrada's Templar Night, typically in summer, culminating in a grand medieval parade with nearly a thousand participants dressed as knights and ladies, evoking the 12th-century Order of the Temple's presence at the local castle.[121] Integrated into broader fiestas like those of La Encina in September, these include staged historical scenes and torchlit processions that commemorate the Templars' role in protecting pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago through El Bierzo, blending education with spectacle based on documented medieval charters.[122] Social structures revolve around cofradías and hermandades, religious brotherhoods that originated in medieval devotional guilds and persist in organizing processions, providing mutual support during rituals, and fostering community bonds through membership dues and charitable acts, as seen in their coordination of Holy Week logistics.[118] These groups, numbering several active ones like the Hermandad de Jesús Nazareno with documented activities since the early modern period, extend beyond religion into social welfare, echoing mutual aid networks from El Bierzo's industrial past.[123] Peñas, informal social clubs, play a key role in festive gatherings, hosting annual encuentros in towns like Ponferrada and Villafranca del Bierzo, where members engage in games, karaoke, communal dinners, and parades during patron saint celebrations, promoting camaraderie among locals and sustaining traditions of collective recreation.[124] With events drawing up to a thousand participants, such as the 2025 II Concentración de Peñas in Ponferrada, these clubs facilitate intergenerational ties and local identity, often rooted in neighborhood or occupational affiliations from the region's mining and agrarian history.[125]Cuisine and Culinary Traditions

The cuisine of El Bierzo emphasizes hearty, seasonally sourced ingredients reflective of its rural, mountainous terroir, with pork derivatives, legumes, and chestnuts forming staples due to historical self-sufficiency in farming and foraging. Traditional preparations prioritize slow cooking methods like boiling or stewing to maximize flavor from local produce, often incorporating wild greens (berzas) and tubers harvested from the region's valleys.[126][127] Central to Bercian gastronomy is botillo, a coarse embutido crafted from pork ribs, tail, tongue, and other offal pieces, seasoned with salt, garlic, and pimentón, then stuffed into beef intestines or cecum and naturally cured for 30-60 days. It is typically boiled for 1.5-2 hours in water with cabbage, potatoes, and chorizo, yielding a broth that underscores the dish's caloric density suited to cold winters. The product received Indicación Geográfica Protegida (IGP) status in 2000, regulating production to within El Bierzo and adjacent Laciana comarcas using native pig breeds and specific maturation in cellars.[126][128][127] Complementing botillo is pote, a rustic bean stew (fabada-like) featuring white beans (fabes), greens, and cured meats simmered for hours to develop depth, often served family-style as a one-pot meal drawing from agrarian traditions. Local red wines from the Bierzo Denominación de Origen, predominantly Mencía varietal, provide ideal pairings for these dishes, their bright acidity and red fruit notes cutting through the meats' richness without overpowering herbal undertones.[129][130] Desserts leverage abundant chestnuts, harvested from ancient sweet chestnut groves, in forms like tarta de castañas—a creamy pie of puréed, sweetened nuts encased in pastry—or simply boiled and preserved in syrup for direct consumption. The pilgrimage routes of the Camino de Santiago, traversing El Bierzo since medieval times, facilitated ingredient exchanges that subtly enriched local repertoires with Galician influences on stews and preservation techniques, though core recipes remain tied to indigenous practices.[131][132][133]Heritage and Tourism

Archaeological and Historical Sites

El Bierzo preserves archaeological evidence spanning prehistoric hillforts to Roman mining complexes and medieval fortifications. Iron Age castros, characteristic of the Castro culture in northwestern Iberia, include the Castro de la Ventosa near Pieros, a fortified settlement with defensive walls and structures dating to the late Iron Age before Roman conquest.[134] These sites reflect pre-Roman indigenous settlement patterns, with remains of dwellings and enclosures adapted to hilltop topography.[135] The Roman era is epitomized by Las Médulas, the empire's largest open-pit gold mine, operational from the 1st to 2nd centuries AD and yielding an estimated 1.5 million kilograms of gold through ruina montium—a hydraulic method channeling water to erode quartz veins and collapse hillsides.[136] This technique, powered by aqueducts diverting rivers over 100 kilometers, transformed the landscape into surreal pinnacles visible today, with explorable galleries like the Cueva del Lago revealing mining shafts and water conduits.[137] Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002 for its testimony to ancient engineering, the 3,000-hectare area underscores Roman resource extraction's scale and environmental impact.[138] Medieval heritage centers on the Castle of Ponferrada, erected in the 12th century by the Knights Templar following King Ferdinand II's 1178 grant to fortify the site against threats.[139] The stronghold, with its polygonal walls and towers, guarded strategic river crossings until the order's 1312 suppression, after which it passed to crown control.[140] Complementing this are hermitages tied to El Bierzo's eremitic tradition, documented from the 7th century in the "Tebaida Berciana" region of secluded valleys. In Corullón, the 12th-century Romanesque Church of San Miguel exemplifies surviving monastic architecture, featuring corbel carvings and declared a cultural asset in 1931.[141] These sites, often Mozarabic-influenced, highlight early Christian asceticism amid Visigothic and Asturian influences.[142]