Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Blacklist (computing)

View on Wikipedia

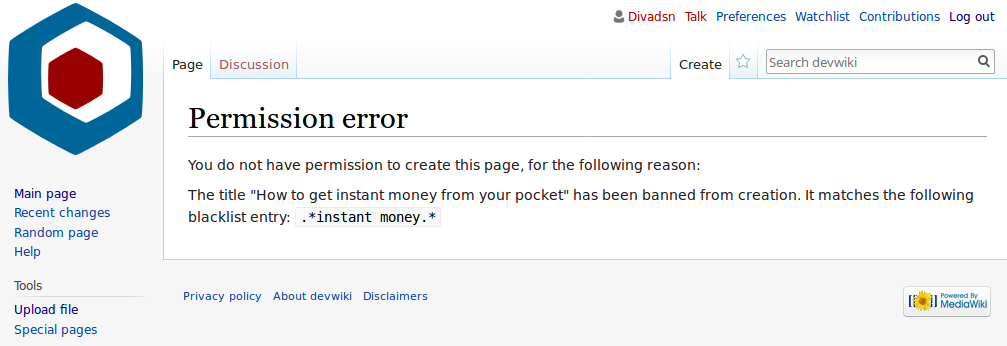

In computing, a blacklist, disallowlist, blocklist, or denylist is a basic access control mechanism that allows through all elements (email addresses, users, passwords, URLs, IP addresses, domain names, file hashes, etc.), except those explicitly mentioned. Those items on the list are denied access. The opposite is a whitelist, allowlist, or passlist, in which only items on the list are let through whatever gate is being used. A greylist contains items that are temporarily blocked (or temporarily allowed) until an additional step is performed.

Blacklists can be applied at various points in a security architecture, such as a host, web proxy, DNS servers, email server, firewall, directory servers or application authentication gateways. The type of element blocked is influenced by the access control location.[1] DNS servers may be well-suited to block domain names, for example, but not URLs. A firewall is well-suited for blocking IP addresses, but less so for blocking malicious files or passwords.

Example uses include a company that might prevent a list of software from running on its network, a school that might prevent access to a list of websites from its computers, or a business that wants to ensure their computer users are not choosing easily guessed, poor passwords.

Examples of systems protected

[edit]Blacklists are used to protect a variety of systems in computing. The content of the blacklist is likely needs to be targeted to the type of system defended.[2]

Information systems

[edit]An information system includes end-point hosts like user machines and servers. A blacklist in this location may include certain types of software that are not allowed to run in the company environment. For example, a company might blacklist peer to peer file sharing on its systems. In addition to software, people, devices and Web sites can also be blacklisted.[3]

Most email providers have an anti-spam feature that essentially blacklists certain email addresses if they are deemed unwanted. For example, a user who wearies of unstoppable emails from a particular address may blacklist that address, and the email client will automatically route all messages from that address to a junk-mail folder or delete them without notifying the user.

An e-mail spam filter may keep a blacklist of email addresses, any mail from which would be prevented from reaching its intended destination. It may also use sending domain names or sending IP addresses to implement a more general block.

In addition to private email blacklists, there are lists that are kept for public use, including:

- China Anti-Spam Alliance[4]

- Fabel Spamsources[5]

- Spam and Open Relay Blocking System

- The DrMX Project

Web browsing

[edit]The goal of a blacklist in a web browser is to prevent the user from visiting a malicious or deceitful web page via filtering locally. A common web browsing blacklist is Google's Safe Browsing, which is installed by default in Firefox, Safari, and Chrome.

Usernames and passwords

[edit]Blacklisting can also apply to user credentials. It is common for systems or websites to blacklist certain reserved usernames that are not allowed to be chosen by the system or website's user populations. These reserved usernames are commonly associated with built-in system administration functions. Also usually blocked by default are profane words and racial slurs.

Password blacklists are very similar to username blacklists but typically contain significantly more entries than username blacklists. Password blacklists are applied to prevent users from choosing passwords that are easily guessed or are well known and could lead to unauthorized access by malicious parties. Password blacklists are deployed as an additional layer of security, usually in addition to a password policy, which sets the requirements of the password length and/or character complexity. This is because there are a significant number of password combinations that fulfill many password policies but are still easily guessed (i.e., Password123, Qwerty123).

Distribution methods

[edit]Blacklists are distributed in a variety of ways. Some use simple mailing lists. A DNSBL is a common distribution method that leverages the DNS itself. Some lists make use of rsync for high-volume exchanges of data.[6] Web-server functions may be used; either simple GET requests may be used or more complicated interfaces such as a RESTful API.

Examples

[edit]- Companies like Google, Symantec and Sucuri keep internal blacklists of sites known to have malware and they display a warning before allowing the user to click them.

- Content-control software such as DansGuardian and SquidGuard may work with a blacklist in order to block URLs of sites deemed inappropriate for a work or educational environment. Such blacklists can be obtained free of charge or from commercial vendors such as Squidblacklist.org.

- There are also free blacklists for Squid (software) proxy, such as Blackweb

- A firewall or IDS may also use a blacklist to block known hostile IP addresses and/or networks. An example for such a list would be the OpenBL project.

- Many copy protection schemes include software blacklisting.

- The company Password RBL offers a password blacklist for Microsoft's Active Directory, web sites and apps, distributed via a RESTful API.

- Members of online auction sites may add other members to a personal blacklist. This means that they cannot bid on or ask questions about your auctions, nor can they use a "buy it now" function on your items.

- Yet another form of list is the yellow list which is a list of email server IP addresses that send mostly good email but do send some spam. Examples include Yahoo, Hotmail, and Gmail.[citation needed] A yellow listed server is a server that should never be accidentally blacklisted. The yellow list is checked first and if listed then blacklist tests are ignored.

- In Linux modprobe, the

blacklist modulenameentry in a modprobe configuration file indicates that all of the particular module's internal aliases are to be ignored. There are cases where two or more modules both support the same devices, or a module invalidly claims to support a device. - Many web browsers have the ability to consult anti-phishing blacklists in order to warn users who unwittingly aim to visit a fraudulent website.

- Many peer-to-peer file sharing programs support blacklists that block access from sites known to be owned by companies enforcing copyright. An example is the Bluetack[7] blocklist set.

Usage considerations

[edit]As expressed in a recent conference paper focusing on blacklists of domain names and IP addresses used for Internet security, "these lists generally do not intersect. Therefore, it appears that these lists do not converge on one set of malicious indicators."[8][9] This concern combined with an economic model[10] means that, while blacklists are an essential part of network defense, they need to be used in concert with whitelists and greylists.

Controversy over terminology

[edit]Some major technology companies and institutions have publicly distanced themselves from the term blacklist due to a perceived connection with racism, instead recommending the terms denylist or blocklist.[11][12][13][14][15][16] The term's connection with racism, as well as the value in avoiding its use has been disputed.[15][17][better source needed]

Controversy over use of the term

[edit]In 2018, a journal commentary on a report on predatory publishing[18] was released which claimed that "white" and "black" are racially-charged terms that need to be avoided in instances such as "whitelist" and "blacklist", and that the first recorded usage of "blacklist" was during "the time of mass enslavement and forced deportation of Africans to work in European-held colonies in the Americas". The article hit mainstream in Summer 2020 following the George Floyd protests in America.[19]

A number of technology companies replaced "whitelist" and "blacklist" with new alternatives such as "allow list" and "deny list", alongside similar terminology changes regarding the terms "Master" and "Slave".[20] For example, in August 2018, Ruby on Rails changed all occurrences of "blacklist" and "whitelist" to "restricted list" and "permitted list".[21] Other companies responded to this controversy in June and July 2020:

- GitHub announced that it would replace many "terms that may be offensive to developers in the black community".[22]

- Apple Inc. announced at its developer conference that it would be adopting more inclusive technical language and replacing the term "blacklist" with "deny list" and the term "whitelist" with "allow list".[23]

- Linux Foundation said it would use neutral language in kernel code and documentation in the future and avoid terms such as "blacklist" and "slave" going forward.[24]

- The Twitter Engineering team stated its intention to move away from a number of terms, including "blacklist" and "whitelist".[25]

- Red Hat announced that it would make open source more inclusive and avoid these and other terms.[26]

ZDNet reports that the list of technology companies making such decisions "includes Twitter, GitHub, Microsoft, LinkedIn, Ansible, Red Hat, Splunk, Android, Go, MySQL, PHPUnit, Curl, OpenZFS, Rust, JP Morgan, and others."[27]

The issue and subsequent changes caused controversy in the computing industry, where "whitelist" and "blacklist" are prevalent (e.g. IP whitelisting[28]). Those[who?] that oppose these changes question the term's attribution to race, claiming that the term "blacklist" arose from the practice of using black books in medieval England.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Shimeall, Timothy; Spring, Jonathan (2013-11-12). Introduction to Information Security: A Strategic-Based Approach. Newnes. ISBN 9781597499729.

- ^ "Domain Blacklist Ecosystem – A Case Study". insights.sei.cmu.edu. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ^ Rainer, Watson (2012). Introduction to Information Systems. Wiley Custom Learning Solutions. ISBN 978-1-118-45213-4.

- ^ "反垃圾邮件联盟". Archived from the original on 2015-08-11. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ^ "Fabelsources – Blacklist".

- ^ "Guidelines". www.surbl.org. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ^ "B.I.S.S. Forums – FAQ – Questions about the Blocklists". Bluetack Internet Security Solutions. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- ^ Metcalf, Leigh; Spring, Jonathan M. (2015-01-01). "Blacklist Ecosystem Analysis". Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Workshop on Information Sharing and Collaborative Security. pp. 13–22. doi:10.1145/2808128.2808129. ISBN 9781450338226. S2CID 4720116.

- ^ Kührer, Marc; Rossow, Christian; Holz, Thorsten (2014-09-17). "Paint It Black: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Malware Blacklists". In Stavrou, Angelos; Bos, Herbert; Portokalidis, Georgios (eds.). Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 8688. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11379-1_1. ISBN 9783319113784. S2CID 12276874.

- ^ Spring, Jonathan M. (2013-09-17). Modeling malicious domain name take-down dynamics: Why eCrime pays. 2013 ECrime Researchers Summit (eCRS 2013). IEEE. pp. 1–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.645.3543. doi:10.1109/eCRS.2013.6805779. ISBN 978-1-4799-1158-5. S2CID 8812531.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin (2020-06-14). "GitHub to replace "master" with alternative term to avoid slavery references". ZDNET. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ "George Floyd: Twitter drops 'master', 'slave' and 'blacklist'". BBC News. 2020-07-03. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin (2020-07-11). "Linux team approves new terminology, bans terms like 'blacklist' and 'slave'". ZDNET. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Kan, Michael (2020-07-17). "Apple to Remove 'Master/Slave' and 'Blacklist' Terms From Coding Platforms". PCMag. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ a b Conger, Kate (2021-04-13). "'Master,' 'Slave' and the Fight Over Offensive Terms in Computing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Milanesi, Carolina (2021-06-29). "The Importance Of Inclusive Language And Design In Tech". Forbes. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Jocom, Juan Miguel (2022-03-24). "Op-Ed | "Blacklist" and "whitelist" aren't racist, you are". The Seattle Collegian. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Houghton, F., & Houghton, S. (2018). "“Blacklists” and “whitelists”: a salutary warning concerning the prevalence of racist language in discussions of predatory publishing."

- ^ Taylor, Derrick Bryson (2020-07-10). "George Floyd Protests: A Timeline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ a b Cimpanu, Catalin. "GitHub to replace "master" with alternative term to avoid slavery references". ZDNet. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ "Merge pull request #33681 from minaslater/replace-white-and-blacklist · rails/rails@de6a200 · GitHub". Github.com. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- ^ "GitHub to replace "master" with alternative term to avoid slavery references". ZDNet. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ "Apple banishes 'blacklist' and 'master branch' in push for inclusive language". msn.com. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ^ "pull request for inclusive-terminology". git.kernel.org. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ "We're starting with a set of words we want to move away from using in favor of more inclusive language". twitter.com. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ "Making open source more inclusive by eradicating problematic language". redhat.com. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ "Linux team approves new terminology, bans terms like 'blacklist' and 'slave'". ZDNet. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ "IP Whitelisting - Documentation". help.gooddata.com. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

Blacklist (computing)

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Principles and Purpose

A blacklist in computing constitutes a predefined list of discrete entities—such as IP addresses, domains, email senders, applications, or processes—previously identified as untrustworthy, unauthorized, or malicious, which are systematically denied access, execution, or processing within a system.[1] This exclusionary mechanism operates on the principle of reactive denial, relying on accumulated empirical evidence of threat behaviors to filter out known risks, thereby implementing a form of negative access control where default permission is overridden only for matched entries.[13] The core purpose of blacklisting is to mitigate causal risks from repeated or patterned adversarial actions, such as spam dissemination, malware propagation, or unauthorized intrusions, by preemptively blocking interactions that could lead to resource compromise or operational disruption.[4] Unlike permissive models, it prioritizes efficiency against high-volume, identifiable threats through simple pattern matching, enabling scalable enforcement in resource-constrained environments like firewalls or email gateways.[14] This approach assumes that documented malicious histories provide reliable indicators for future prevention, though its effectiveness hinges on timely updates to reflect evolving tactics.[15]Comparison to Whitelists and Greylists

Blacklists operate on a default-permit policy, explicitly denying access to identified threats such as malicious IP addresses or domains, whereas whitelists enforce a default-deny approach by permitting only pre-approved entities, thereby blocking all unknowns.[16] [12] This fundamental contrast influences their efficacy: blacklists are reactive, targeting known risks like those cataloged in real-time DNS-based blackhole lists (DNSBLs) for email, but they fail against novel threats, as attackers can evade by using unlisted IPs or domains.[16] Whitelists, conversely, provide stronger proactive defense in controlled environments, such as application whitelisting in enterprise endpoints, where only verified software executes, reducing zero-day exploit risks by up to 99% in some implementations.[12] [17] Greylists introduce a behavioral intermediary, temporarily deferring or quarantining suspicious entities for verification, often exploiting the tendency of legitimate systems to retry connections while many automated spam or attack tools do not.[18] In email spam filtering, greylisting—first proposed in a 2003 method by Evan Harris—rejects initial SMTP connections from unknown senders, accepting retries after a delay (typically 5-10 minutes), which can filter 50-90% of spam without permanent blocks.[18] [17] This hybrid mitigates blacklist maintenance burdens and whitelist rigidity but introduces latency for valid traffic and potential failures if compliant senders lack retry logic.[12]| Aspect | Blacklist | Whitelist | Greylist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | Allow by default; block known bad | Deny by default; allow known good | Defer unknowns for verification |

| Pros | Low maintenance for common threats; minimal disruption to legitimate traffic | High security against unknowns; limits attack surface | Reduces spam volume via behavior; avoids exhaustive lists |

| Cons | Misses emerging threats; lists bloat over time | High false positives for new legit items; requires ongoing curation | Delays delivery; ineffective against persistent attackers |

| Best Use | Broad network/email filtering (e.g., DNSBLs) | Strict environments (e.g., endpoint app control) | Email MTA defenses (e.g., Postfix integration) |

Historical Development

Origins in Networking and Early Security Practices

TCP Wrappers, introduced by Wietse Venema in 1990, represented one of the earliest formalized implementations of blacklisting in Unix-based network security. Developed initially to monitor and log connections amid rising intrusions on networked workstations at Eindhoven University of Technology, the tool wrapped around inetd-managed services to enforce host-based access controls. It employed two configuration files:/etc/hosts.allow for explicit permissions and /etc/hosts.deny as a deny list, blocking connections from specified IP addresses, hostnames, or domains unless overridden by allow rules.[19][20]

This blacklist mechanism operated on a default-permit model, allowing all traffic except that matching deny entries, which facilitated reactive blocking of known threats like crackers probing for vulnerabilities in services such as FTP or telnet. Venema's design included logging capabilities to identify attack patterns, enabling administrators to populate deny lists dynamically based on observed malicious activity. By 1992, the approach was documented in detail, emphasizing its role in simple yet effective perimeter defense before dedicated firewalls became widespread.[19][21]

Preceding TCP Wrappers, early network security in ARPANET and nascent TCP/IP environments (from the 1970s) relied on informal practices like null-routing suspicious hosts or manual daemon reconfiguration, but lacked standardized deny lists. The shift toward explicit blacklists in tools like TCP Wrappers addressed the limitations of trust-based models, as interconnected Unix systems faced increasing unauthorized access attempts in the late 1980s. This laid groundwork for broader adoption in access control, influencing later systems despite eventual supersession by stateful firewalls and IP-level filtering.[22]