Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coach (baseball)

View on Wikipedia

In baseball, a number of coaches assist in the smooth functioning of a team. They are assistants to the manager, who determines the starting lineup and batting order, decides how to substitute players during the game, and makes strategy decisions. Beyond the manager, more than a half dozen coaches may assist the manager in running the team. Essentially, baseball coaches are analogous to assistant coaches in other sports, as the baseball manager is to the head coach.

Roles of professional baseball coaches

[edit]

Baseball is unique in that the manager and coaches typically all wear numbered uniforms similar to those of the players, due to the early practice of managers frequently being selected from the player roster. The wearing of uniforms continued even after the practice of playing managers and coaches waned; notable exceptions to this were Baseball Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack, who always wore a black suit during his 50 years at the helm of the Philadelphia Athletics, and Burt Shotton, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the late 1940s, who wore a Dodger cap and a team jacket over street clothes in the dugout. After the widespread adoption of numbered uniforms in the early 1930s, Joe McCarthy, another Hall of Fame manager, wore a full uniform but no number on his back for the remainder of his career with the New York Yankees, then the Boston Red Sox. All three men retired during or after the 1950 season.

Full-time coaches in professional baseball date to 1909, when John McGraw of the New York Giants engaged Arlie Latham and Wilbert Robinson as coaches.[1] By the 1920s, most major league teams had two full-time coaches stationed in foul territory near first base and third base when their team was batting, although the manager often doubled as third-base coach, and specialists such as pitching coaches were rare. After World War II, most major league teams listed between three and five coaches on their roster, as managers increasingly ran their teams from the dugout full-time, and appointed pitching and bullpen coaches to assist them and the baseline coaches. Batting and bench coaches came into vogue during the 1960s and later.[1] Because of the proliferation of uniformed coaches in the modern game, by the late 2000s Major League Baseball had restricted the number of uniformed staff to six coaches and one manager during the course of a game.[2] Beginning with the 2013 season, clubs have been permitted to employ a seventh uniformed coach, designated the assistant hitting coach, at their own discretion.[3]

Bench coach

[edit]

The first bench coach in baseball was George Huff, who took that helm for the Illinois Fighting Illini baseball in 1905; at the time, it meant a coach present throughout the season.[4]

More recently, the bench coach is a team's second-in-command. The bench coach serves as an in-game advisor to the manager, offering situational advice, and exchanging ideas in order to assist the manager in making strategy decisions along with relaying scouting information from the front office to the players.[5] If the manager is ejected, suspended, or unable to attend a game for any reason, the bench coach assumes the position of acting manager. If the manager is fired or resigns during the season, it is usually the bench coach who is promoted to interim manager. The bench coach's responsibilities also include helping to set up the day's practice and stretching routines before a game, as well as coordinating spring training routines and practices.[6]

Pitching and bullpen coaches

[edit]A pitching coach mentors and trains teams' pitchers. Pitching coaches can alter a pitcher's arm angle, placement on the pitching rubber or pitch selection in order to improve the player's performance. The coach advises the manager on the condition of pitchers and their arms, and serves as an in-game coach for the pitcher currently on the mound. When a manager makes a visit to the mound, he or she typically is doing so to make a pitching change or to discuss situational defense. A pitching coach also helps pitchers with their mechanics and pitch selection against specific batters who may be coming up. However, to talk about mechanics or how to pitch to a particular batter, the pitching coach is the one who will typically visit the mound.[7] The pitching coach is generally a former pitcher. One exception is Dave Duncan, the former pitching coach of the St. Louis Cardinals, who was a catcher. Prior to the early 1950s, pitching coaches were usually former catchers.[8]

The bullpen coach is similar to a pitching coach, but works primarily with relief pitchers in the bullpen. Bullpen coaches do not make mound visits; rather, they stay in the bullpen the entire game, working with relievers who are warming up to enter the game, while also offering advice on pitching mechanics and pitch selection. Generally, the bullpen coach is either a former pitcher or catcher.

Offensive coaches

[edit]Hitting coach

[edit]A hitting coach, as the name suggests, works with a team's players to improve their batting techniques and form. They monitor players' swings during the game and over the course of the season, advising them when necessary between at bats on adjustments to make. They also oversee batters' performance during practices, cage sessions, and pre-game batting practice. With the advent of technology, hitting coaches are increasingly utilizing video to analyze their hitters along with scouting the opposing pitchers. Video has allowed hitting coaches to clearly illustrate problem areas in the swing, making the adjustment period quicker for the player being analyzed. This process is typically called video analysis.

Base coaches

[edit]

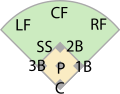

Two on-field coaches are present when the team is batting. Stationed in designated coaches' boxes in foul territory near first and third base are the first-base coach and third-base coach. They assist in the direction of baserunners, help prevent pickoffs, and relay signals sent from the manager in the dugout to runners and batters. While the first-base coach is primarily responsible for the batter as to whether he stops at first base or not, or for a runner already on first, the third-base coach carries more responsibility. Such duties include holding or sending runners rounding second and third bases as well as having to make critical, split-second decisions about whether to try to score a runner on a hit, sacrifice fly or error; additionally, they account for the arm strength of the opposing team's fielder and the speed and position of the baserunner.

Additional coaching responsibilities

[edit]The bench coach, third-base coach, and first-base coach often are assigned additional responsibility for assisting players in specific areas, particularly defense. Common designations include outfield instructor, infield instructor, catching instructor, and baserunning instructor.[9] When a coaching staff is assembled, the selection of the first-base coach is frequently made with the purpose of filling a gap in these coaching responsibilities, as the actual in-game duties of a first-base coach are relatively light.

Other coaches

[edit]Teams may also employ individuals to work with players in other areas or activities. These positions sometimes include the word "coach" in their titles. Individuals holding these positions usually do not dress in uniform during games, as the number of uniformed coaches is restricted by Major League Baseball rules. The most prominent of these positions are the athletic trainer and the strength and conditioning coach. All Major League Baseball teams employ an athletic trainer; most employ a strength and conditioning coach. Other positions include bullpen catcher and batting practice pitcher. Some teams also employ additional coaches without specific responsibilities.

Minor and amateur leagues

[edit]

Major League Baseball teams will have one or more person specifically assigned to each coaching position described above. However, minor league and amateur teams typically have coaches fulfill multiple responsibilities. A typical minor league/amateur team coaching structure will have a manager, a pitching coach, and a hitting coach, each of whom also assumes the responsibilities of the first- and third-base coaches, bullpen coach, etc. In college baseball in the U.S., the title "manager" is not used; the person who fills the role of a professional manager is instead called the "head coach".

Youth baseball

[edit]Responsibilities of a youth baseball coach include providing a safe environment for everyone. A coach is responsible for inspecting fields and equipment that is used for practice and competition to ensure it is safe. Communication is key when dealing with youth baseball as being positive to other coaching staff, umpires, administrators and others shows that they have a players best interest at heart. Coaches are there not to just work with the stars to get them better but everyone so it is a fair learning experience.[10] Teaching the fundamental skills of baseball is important as a youth coach because in the end baseball is a game, therefore coaches want players to have fun. Having a fun but productive practice environment is important. The rules of baseball are necessary in youth baseball. Many rules such as sliding, the strike zone, and defensive rules are needed.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Thorne, John, and Palmer, Pete, eds., Total Baseball. New York: Warner Books, 1989, page 2,153

- ^ article, Associated Press, March 30, 2007

- ^ Neyer, Rob (January 15, 2013). "Coming to a dugout near you: Interpreters! Assistant hitting coaches!". SBNation.com.

- ^ Gagnon, Cappy (2004). Notre Dame Baseball Greats: From Anson to Yaz. Arcadia Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 0738532622. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

Before the 1905 season, when George Huff took the helm for the University of Illinois, no college had ever employed a bench coach. Before that time (and for another 5-10 years at most colleges), anyone listed as 'coach' was either a professional player hired as the pre-season teacher of baseball, or was the player-coach or captain of the team.

- ^ "The Role of the Bench Coach" – The Birdhouse Archived October 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "More than just a side job: For a manager, bench coach is a trusted confidant" – Boston Globe

- ^ "Pitching Coach | Glossary". MLB.com.

- ^ Zimniuch, Fran (2010). Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball. Chicago: Triumph Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-60078-312-8.

- ^ "The Mets' Next Third Base Coach" NY Daily News

- ^ "Coaching Baseball 101".

- ^ "Your responsibilities as a youth baseball coach". Human Kinetics. Retrieved 2022-11-15.