Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

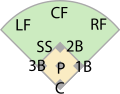

Power pitcher

View on Wikipedia

Power pitcher is a term in baseball for a pitcher who relies on pitch velocity at the expense of accuracy. Power pitchers usually record a high number of strikeouts, and statistics such as strikeouts per 9 innings pitched are common measures of power.[1] An average pitcher strikes out about 5 batters per nine innings while a power pitcher will often strike out one or more every inning.[1]

The prototypical power pitcher is Hall of Fame member Nolan Ryan, who struck out a Major League Baseball record 5,714 batters in 5,386 innings. Ryan recorded seven no-hitters, appeared in eight Major League Baseball All-Star Games but also holds the record for most walks issued (2,795).[2] Other prominent power pitchers include Hall of Famers Walter Johnson, Sandy Koufax, Pedro Martínez, Randy Johnson, and Bob Feller. Feller himself famously led his league in strikeouts and walks several times.[3]

The traditional school of thought on power pitching was known as "throw till you blow".[4] However, multimillion-dollar contracts have changed mentalities.[4] The number of pitches thrown is now counted by a team's staff, with particular attention paid to young power arms.[4] The care which some of the older power pitchers took with their arms has allowed for long careers and further opportunity after they have stopped playing.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "SCOUTING REPORT". Sportsmogul.com. Sports Mogul Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ "Nolan Ryan Career Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Bob Feller Career Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ a b c Shaw, Bud. (March 21, 1999) The Plain Dealer. Developing a power pitcher can be a delicate process. Pitch counts are one way to reduce stress on young arms. Section:Sports; Page 3C.

- ^ Brown, Tim. (March 7, 2005) Los Angeles Times Life needn't end at 40 for power pitchers, and Clemens, Johnson and others are proving it. Section: Sports; Fitness and Starts; Page 1.

Further reading

[edit]- Neyer, Rob; James, Bill (2004). The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-6158-5.

- Passan, Jeff (2016). The Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in Sports. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0062-4003-76.