Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Case-based reasoning

View on WikipediaThis article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, the article doesn't describe case-based reasoning from a technical point of view, leaving readers uncertain about how programmers actually implement it. (December 2021) |

Case-based reasoning (CBR), broadly construed, is the process of solving new problems based on the solutions of similar past problems.[1][2]

In everyday life, an auto mechanic who fixes an engine by recalling another car that exhibited similar symptoms is using case-based reasoning. A lawyer who advocates a particular outcome in a trial based on legal precedents or a judge who creates case law is using case-based reasoning. So, too, an engineer copying working elements of nature (practicing biomimicry) is treating nature as a database of solutions to problems. Case-based reasoning is a prominent type of analogy solution making.

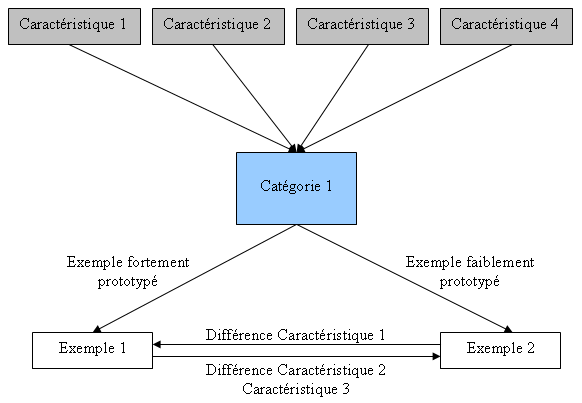

It has been argued[by whom?] that case-based reasoning is not only a powerful method for computer reasoning, but also a pervasive behavior in everyday human problem solving; or, more radically, that all reasoning is based on past cases personally experienced. This view is related to prototype theory, which is most deeply explored in cognitive science.

Process

[edit]

Case-based reasoning has been formalized[clarification needed] for purposes of computer reasoning as a four-step process:[3]

- Retrieve: Given a target problem, retrieve cases relevant to solving it from memory. A case consists of a problem, its solution, and, typically, annotations about how the solution was derived. For example, suppose Fred wants to prepare blueberry pancakes. Being a novice cook, the most relevant experience he can recall is one in which he successfully made plain pancakes. The procedure he followed for making the plain pancakes, together with justifications for decisions made along the way, constitutes Fred's retrieved case.

- Reuse: Map the solution from the previous case to the target problem. This may involve adapting the solution as needed to fit the new situation. In the pancake example, Fred must adapt his retrieved solution to include the addition of blueberries.

- Revise: Having mapped the previous solution to the target situation, test the new solution in the real world (or a simulation) and, if necessary, revise. Suppose Fred adapted his pancake solution by adding blueberries to the batter. After mixing, he discovers that the batter has turned blue – an undesired effect. This suggests the following revision: delay the addition of blueberries until after the batter has been ladled into the pan.

- Retain: After the solution has been successfully adapted to the target problem, store the resulting experience as a new case in memory. Fred, accordingly, records his new-found procedure for making blueberry pancakes, thereby enriching his set of stored experiences, and better preparing him for future pancake-making demands.

Comparison to other methods

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

At first glance, CBR may seem similar to the rule induction algorithms[note 1] of machine learning. Like a rule-induction algorithm, CBR starts with a set of cases or training examples; it forms generalizations of these examples, albeit implicit ones, by identifying commonalities between a retrieved case and the target problem.[4]

If for instance a procedure for plain pancakes is mapped to blueberry pancakes, a decision is made to use the same basic batter and frying method, thus implicitly generalizing the set of situations under which the batter and frying method can be used. The key difference, however, between the implicit generalization in CBR and the generalization in rule induction lies in when the generalization is made. A rule-induction algorithm draws its generalizations from a set of training examples before the target problem is even known; that is, it performs eager generalization.

For instance, if a rule-induction algorithm were given recipes for plain pancakes, Dutch apple pancakes, and banana pancakes as its training examples, it would have to derive, at training time, a set of general rules for making all types of pancakes. It would not be until testing time that it would be given, say, the task of cooking blueberry pancakes. The difficulty for the rule-induction algorithm is in anticipating the different directions in which it should attempt to generalize its training examples. This is in contrast to CBR, which delays (implicit) generalization of its cases until testing time – a strategy of lazy generalization. In the pancake example, CBR has already been given the target problem of cooking blueberry pancakes; thus it can generalize its cases exactly as needed to cover this situation. CBR therefore tends to be a good approach for rich, complex domains in which there are myriad ways to generalize a case.

In law, there is often explicit delegation of CBR to courts, recognizing the limits of rule based reasons: limiting delay, limited knowledge of future context, limit of negotiated agreement, etc. While CBR in law and cognitively inspired CBR have long been associated, the former is more clearly an interpolation of rule based reasoning, and judgment, while the latter is more closely tied to recall and process adaptation. The difference is clear in their attitude toward error and appellate review.

Another name for case-based reasoning in problem solving is symptomatic strategies. It does require à priori domain knowledge that is gleaned from past experience which established connections between symptoms and causes. This knowledge is referred to as shallow, compiled, evidential, history-based as well as case-based knowledge. This is the strategy most associated with diagnosis by experts. Diagnosis of a problem transpires as a rapid recognition process in which symptoms evoke appropriate situation categories.[5] An expert knows the cause by virtue of having previously encountered similar cases. Case-based reasoning is the most powerful strategy, and that used most commonly. However, the strategy won't work independently with truly novel problems, or where deeper understanding of whatever is taking place is sought.

An alternative approach to problem solving is the topographic strategy which falls into the category of deep reasoning. With deep reasoning, in-depth knowledge of a system is used. Topography in this context means a description or an analysis of a structured entity, showing the relations among its elements.[6]

Also known as reasoning from first principles,[7] deep reasoning is applied to novel faults when experience-based approaches aren't viable. The topographic strategy is therefore linked to à priori domain knowledge that is developed from a more a fundamental understanding of a system, possibly using first-principles knowledge. Such knowledge is referred to as deep, causal or model-based knowledge.[8] Hoc and Carlier[9] noted that symptomatic approaches may need to be supported by topographic approaches because symptoms can be defined in diverse terms. The converse is also true – shallow reasoning can be used abductively to generate causal hypotheses, and deductively to evaluate those hypotheses, in a topographical search.

Criticism

[edit]Critics of CBR[who?] argue that it is an approach that accepts anecdotal evidence as its main operating principle. Without statistically relevant data for backing and implicit generalization, there is no guarantee that the generalization is correct. However, all inductive reasoning where data is too scarce for statistical relevance is inherently based on anecdotal evidence.

History

[edit]CBR traces its roots to the work of Roger Schank and his students at Yale University in the early 1980s. Schank's model of dynamic memory[10] was the basis for the earliest CBR systems: Janet Kolodner's CYRUS[11] and Michael Lebowitz's IPP.[12]

Other schools of CBR and closely allied fields emerged in the 1980s, which directed at topics such as legal reasoning, memory-based reasoning (a way of reasoning from examples on massively parallel machines), and combinations of CBR with other reasoning methods. In the 1990s, interest in CBR grew internationally, as evidenced by the establishment of an International Conference on Case-Based Reasoning in 1995, as well as European, German, British, Italian, and other CBR workshops[which?].

CBR technology has resulted in the deployment of a number of successful systems, the earliest being Lockheed's CLAVIER,[13] a system for laying out composite parts to be baked in an industrial convection oven. CBR has been used extensively in applications such as the Compaq SMART system[14] and has found a major application area in the health sciences,[15] as well as in structural safety management.

There is recent work[which?][when?] that develops CBR within a statistical framework and formalizes case-based inference as a specific type of probabilistic inference. Thus, it becomes possible to produce case-based predictions equipped with a certain level of confidence.[16] One description of the difference between CBR and induction from instances is that statistical inference aims to find what tends to make cases similar while CBR aims to encode what suffices to claim similarly.[17][full citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Rule-induction algorithms are procedures for learning rules for a given concept by generalizing from examples of that concept. For example, a rule-induction algorithm might learn rules for forming the plural of English nouns from examples such as dog/dogs, fly/flies, and ray/rays.

- ^ Kolodner, Janet L. "An introduction to case-based reasoning." Artificial intelligence review 6.1 (1992): 3-34.

- ^ Weir, B. S. (1988). Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Quantitative Genetics (p. 537). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Agnar Aamodt and Enric Plaza, "Case-Based Reasoning: Foundational Issues, Methodological Variations, and System Approaches," Artificial Intelligence Communications 7 (1994): 1, 39-52.

- ^ Richter, Michael M.; Weber, Rosina O. (2013). Case-based reasoning: a textbook. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40167-1. ISBN 9783642401664. OCLC 857646182. S2CID 6295943.

- ^ Gilhooly, Kenneth J. "Cognitive psychology and medical diagnosis." Applied cognitive psychology 4.4 (1990): 261-272.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary.

- ^ Davis, Randall. "Reasoning from first principles in electronic troubleshooting." International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 19.5 (1983): 403-423.

- ^ Milne, Robert. "Strategies for diagnosis." IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 17.3 (1987): 333-339.

- ^ Hoc, Jean-Michel. "A method to describe human diagnostic strategies in relation to the design of human-machine cooperation." International Journal of Cognitive Ergonomics 4.4 (2000): 297-309.

- ^ Roger Schank, Dynamic Memory: A Theory of Learning in Computers and People (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- ^ Janet Kolodner, "Reconstructive Memory: A Computer Model," Cognitive Science 7 (1983): 4.

- ^ Michael Lebowitz, "Memory-Based Parsing Archived 2017-11-18 at the Wayback Machine," Artificial Intelligence 21 (1983), 363-404.

- ^ Bill Mark, "Case-Based Reasoning for Autoclave Management," Proceedings of the Case-Based Reasoning Workshop (1989).

- ^ Trung Nguyen, Mary Czerwinski, and Dan Lee, "COMPAQ QuickSource: Providing the Consumer with the Power of Artificial Intelligence," in Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence (Washington, DC: AAAI Press, 1993), 142-151.

- ^ Begum, S.; M. U Ahmed; P. Funk; Ning Xiong; M. Folke (July 2011). "Case-Based Reasoning Systems in the Health Sciences: A Survey of Recent Trends and Developments". IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part C: Applications and Reviews. 41 (4): 421–434. Bibcode:2011ITHMS..41..421B. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2010.2071862. ISSN 1094-6977. S2CID 22441650.

- ^ Eyke Hüllermeier. Case-Based Approximate Reasoning. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2007.

- ^ Wilson, Robert Andrew, and Frank C. Keil, eds. The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences. MIT press, 2001.

Further reading

[edit]- Aamodt, Agnar, and Enric Plaza. "Case-Based Reasoning: Foundational Issues, Methodological Variations, and System Approaches" Artificial Intelligence Communications 7, no. 1 (1994): 39–52.

- Althoff, Klaus-Dieter, Ralph Bergmann, and L. Karl Branting, eds. Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Case-Based Reasoning. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1999.

- Bergmann, Ralph Experience Management: Foundations, Development Methodology, and Internet-Based Applications. Springer, LNAI 2432, 2002.

- Bergmann, R., Althoff, K.-D., Breen, S., Göker, M., Manago, M., Traphöner, R., and Wess, S. Developing industrial case-based reasoning applications: The INRECA methodology. Springer LNAI 1612, 2003.

- Kolodner, Janet. Case-Based Reasoning. San Mateo: Morgan Kaufmann, 1993.

- Leake, David. "CBR in Context: The Present and Future", In Leake, D., editor, Case-Based Reasoning: Experiences, Lessons, and Future Directions. AAAI Press/MIT Press, 1996, 1-30.

- Leake, David, and Enric Plaza, eds. Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Case-Based Reasoning. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1997.

- Lenz, Mario; Bartsch-Spörl, Brigitte; Burkhard, Hans-Dieter; Wess, Stefan, eds. (1998). Case-Based Reasoning Technology: From Foundations to Applications. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 1400. Springer. doi:10.1007/3-540-69351-3. ISBN 978-3-540-64572-6. S2CID 10517603.

- Oxman, Rivka. Precedents in Design: a Computational Model for the Organization of Precedent Knowledge, Design Studies, Vol. 15 No. 2 pp. 141–157

- Riesbeck, Christopher, and Roger Schank. Inside Case-based Reasoning. Northvale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1989.

- Veloso, Manuela, and Agnar Aamodt, eds. Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Case-Based Reasoning. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1995.

- Watson, Ian. Applying Case-Based Reasoning: Techniques for Enterprise Systems. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann, 1997. https://a.co/d/g84Vai9

External links

[edit]An earlier version of the above article was posted on Nupedia.