Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Problem solving

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

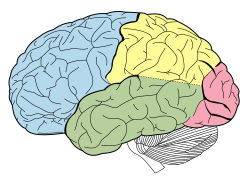

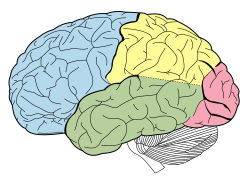

| Cognitive psychology |

|---|

|

| Perception |

| Attention |

| Memory |

| Metacognition |

| Language |

| Metalanguage |

| Thinking |

| Numerical cognition |

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Puzzles |

|---|

|

Problem solving is the process of achieving a goal by overcoming obstacles, a frequent part of most activities. Problems in need of solutions range from simple personal tasks (e.g. how to turn on an appliance) to complex issues in business and technical fields. The former is an example of simple problem solving (SPS) addressing one issue, whereas the latter is complex problem solving (CPS) with multiple interrelated obstacles.[1] Another classification of problem-solving tasks is into well-defined problems with specific obstacles and goals, and ill-defined problems in which the current situation is troublesome but it is not clear what kind of resolution to aim for.[2] Similarly, one may distinguish formal or fact-based problems requiring psychometric intelligence, versus socio-emotional problems which depend on the changeable emotions of individuals or groups, such as tactful behavior, fashion, or gift choices.[3]

Solutions require sufficient resources and knowledge to attain the goal. Professionals such as lawyers, doctors, programmers, and consultants are largely problem solvers for issues that require technical skills and knowledge beyond general competence. Many businesses have found profitable markets by recognizing a problem and creating a solution: the more widespread and inconvenient the problem, the greater the opportunity to develop a scalable solution.

There are many specialized problem-solving techniques and methods in fields such as science, engineering, business, medicine, mathematics, computer science, philosophy, and social organization. The mental techniques to identify, analyze, and solve problems are studied in psychology and cognitive sciences. Also widely researched are the mental obstacles that prevent people from finding solutions; problem-solving impediments include confirmation bias, mental set, and functional fixedness.

Definition

[edit]The term problem solving has a slightly different meaning depending on the discipline. For instance, it is a mental process in psychology and a computerized process in computer science. There are two different types of problems: ill-defined and well-defined; different approaches are used for each. Well-defined problems have specific end goals and clearly expected solutions, while ill-defined problems do not. Well-defined problems allow for more initial planning than ill-defined problems.[2] Solving problems sometimes involves dealing with pragmatics (the way that context contributes to meaning) and semantics (the interpretation of the problem). The ability to understand what the end goal of the problem is, and what rules could be applied, represents the key to solving the problem. Sometimes a problem requires abstract thinking or coming up with a creative solution.

Problem solving has two major domains: mathematical problem solving and personal problem solving. Each concerns some difficulty or barrier that is encountered.[4]

Psychology

[edit]Problem solving in psychology refers to the process of finding solutions to problems encountered in life.[5] Solutions to these problems are usually situation- or context-specific. The process starts with problem finding and problem shaping, in which the problem is discovered and simplified. The next step is to generate possible solutions and evaluate them. Finally a solution is selected to be implemented and verified. Problems have an end goal to be reached; how you get there depends upon problem orientation (problem-solving coping style and skills) and systematic analysis.[6]

Mental health professionals study the human problem-solving processes using methods such as introspection, behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experiment. Social psychologists look into the person-environment relationship aspect of the problem and independent and interdependent problem-solving methods.[7] Problem solving has been defined as a higher-order cognitive process and intellectual function that requires the modulation and control of more routine or fundamental skills.[8]

Empirical research shows many different strategies and factors influence everyday problem solving.[9] Rehabilitation psychologists studying people with frontal lobe injuries have found that deficits in emotional control and reasoning can be re-mediated with effective rehabilitation and could improve the capacity of injured persons to resolve everyday problems.[10] Interpersonal everyday problem solving is dependent upon personal motivational and contextual components. One such component is the emotional valence of "real-world" problems, which can either impede or aid problem-solving performance. Researchers have focused on the role of emotions in problem solving,[11] demonstrating that poor emotional control can disrupt focus on the target task, impede problem resolution, and lead to negative outcomes such as fatigue, depression, and inertia.[12] In conceptualization,[clarification needed]human problem solving consists of two related processes: problem orientation, and the motivational/attitudinal/affective approach to problematic situations and problem-solving skills.[13] People's strategies cohere with their goals[14] and stem from the process of comparing oneself with others.

Cognitive sciences

[edit]Among the first experimental psychologists to study problem solving were the Gestaltists in Germany, such as Karl Duncker in The Psychology of Productive Thinking (1935).[15] Perhaps best known is the work of Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon.[16]

Experiments in the 1960s and early 1970s asked participants to solve relatively simple, well-defined, but not previously seen laboratory tasks.[17][18] These simple problems, such as the Tower of Hanoi, admitted optimal solutions that could be found quickly, allowing researchers to observe the full problem-solving process. Researchers assumed that these model problems would elicit the characteristic cognitive processes by which more complex "real world" problems are solved.

An outstanding problem-solving technique found by this research is the principle of decomposition.[19]

Computer science

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2018) |

Much of computer science and artificial intelligence involves designing automated systems to solve a specified type of problem: to accept input data and calculate a correct or adequate response, reasonably quickly. Algorithms are recipes or instructions that direct such systems, written into computer programs.

Steps for designing such systems include problem determination, heuristics, root cause analysis, de-duplication, analysis, diagnosis, and repair. Analytic techniques include linear and nonlinear programming, queuing systems, and simulation.[20] A large, perennial obstacle is to find and fix errors in computer programs: debugging.

Logic

[edit]Formal logic concerns issues like validity, truth, inference, argumentation, and proof. In a problem-solving context, it can be used to formally represent a problem as a theorem to be proved, and to represent the knowledge needed to solve the problem as the premises to be used in a proof that the problem has a solution.

The use of computers to prove mathematical theorems using formal logic emerged as the field of automated theorem proving in the 1950s. It included the use of heuristic methods designed to simulate human problem solving, as in the Logic Theory Machine, developed by Allen Newell, Herbert A. Simon and J. C. Shaw, as well as algorithmic methods such as the resolution principle developed by John Alan Robinson.

In addition to its use for finding proofs of mathematical theorems, automated theorem-proving has also been used for program verification in computer science. In 1958, John McCarthy proposed the advice taker, to represent information in formal logic and to derive answers to questions using automated theorem-proving. An important step in this direction was made by Cordell Green in 1969, who used a resolution theorem prover for question-answering and for such other applications in artificial intelligence as robot planning.

The resolution theorem-prover used by Cordell Green bore little resemblance to human problem solving methods. In response to criticism of that approach from researchers at MIT, Robert Kowalski developed logic programming and SLD resolution,[21] which solves problems by problem decomposition. He has advocated logic for both computer and human problem solving[22] and computational logic to improve human thinking.[23]

Engineering

[edit]When products or processes fail, problem solving techniques can be used to develop corrective actions that can be taken to prevent further failures. Such techniques can also be applied to a product or process prior to an actual failure event—to predict, analyze, and mitigate a potential problem in advance. Techniques such as failure mode and effects analysis can proactively reduce the likelihood of problems.

In either the reactive or the proactive case, it is necessary to build a causal explanation through a process of diagnosis. In deriving an explanation of effects in terms of causes, abduction generates new ideas or hypotheses (asking "how?"); deduction evaluates and refines hypotheses based on other plausible premises (asking "why?"); and induction justifies a hypothesis with empirical data (asking "how much?").[24] The objective of abduction is to determine which hypothesis or proposition to test, not which one to adopt or assert.[25] In the Peircean logical system, the logic of abduction and deduction contribute to our conceptual understanding of a phenomenon, while the logic of induction adds quantitative details (empirical substantiation) to our conceptual knowledge.[26]

Forensic engineering is an important technique of failure analysis that involves tracing product defects and flaws. Corrective action can then be taken to prevent further failures.

Reverse engineering attempts to discover the original problem-solving logic used in developing a product by disassembling the product and developing a plausible pathway to creating and assembling its parts.[27]

Physics

[edit]In physics, problem solving refers to the process by which one transforms an initial physical situation into a goal state by applying physics-specific reasoning and analysis. This involves identifying the relevant physical principles, making assumptions, formulating and manipulating equations, and checking whether the result is reasonable.[28]

A physics problem is not simply application or recall of a formula, but requires understanding the underlying concepts and navigating through a "problem space" of possible knowledge states toward the goal.

Military science

[edit]In military science, problem solving is linked to the concept of "end-states", the conditions or situations which are the aims of the strategy.[29]: xiii, E-2 Ability to solve problems is important at any military rank, but is essential at the command and control level. It results from deep qualitative and quantitative understanding of possible scenarios. Effectiveness in this context is an evaluation of results: to what extent the end states were accomplished.[29]: IV-24 Planning is the process of determining how to effect those end states.[29]: IV-1

Processes

[edit]Some models of problem solving involve identifying a goal and then a sequence of subgoals towards achieving this goal. Andersson, who introduced the ACT-R model of cognition, modelled this collection of goals and subgoals as a goal stack in which the mind contains a stack of goals and subgoals to be completed, and a single task being carried out at any time.[30]: 51

Knowledge of how to solve one problem can be applied to another problem, in a process known as transfer.[30]: 56

Problem-solving strategies

[edit]Problem-solving strategies are steps to overcoming the obstacles to achieving a goal. The iteration of such strategies over the course of solving a problem is the "problem-solving cycle".[31]

Common steps in this cycle include recognizing the problem, defining it, developing a strategy to fix it, organizing knowledge and resources available, monitoring progress, and evaluating the effectiveness of the solution. Once a solution is achieved, another problem usually arises, and the cycle starts again.

Insight is the sudden aha! solution to a problem, the birth of a new idea to simplify a complex situation. Solutions found through insight are often more incisive than those from step-by-step analysis. A quick solution process requires insight to select productive moves at different stages of the problem-solving cycle. Unlike Newell and Simon's formal definition of a move problem, there is no consensus definition of an insight problem.[32]

Some problem-solving strategies include:[33]

- Abstraction

- solving the problem in a tractable model system to gain insight into the real system

- Analogy

- adapting the solution to a previous problem which has similar features or mechanisms

- Brainstorming

- (especially among groups of people) suggesting a large number of solutions or ideas and combining and developing them until an optimum solution is found

- Bypasses

- transform the problem into another problem that is easier to solve, bypassing the barrier, then transform that solution back to a solution to the original problem.

- Critical thinking

- analysis of available evidence and arguments to form a judgement via rational, skeptical, and unbiased evaluation

- Divide and conquer

- breaking down a large, complex problem into smaller, solvable problems

- Help-seeking

- obtaining external assistance to deal with obstacles

- Hypothesis testing

- assuming a possible explanation to the problem and trying to prove (or, in some contexts, disprove) the assumption

- Lateral thinking

- approaching solutions indirectly and creatively

- Means-ends analysis

- choosing an action at each step to move closer to the goal

- Morphological analysis

- assessing the output and interactions of an entire system

- Observation / Question

- in the natural sciences an observation is an act or instance of noticing or perceiving and the acquisition of information from a primary source. A question is an utterance which serves as a request for information.[citation needed]

- Proof of impossibility

- try to prove that the problem cannot be solved. The point where the proof fails will be the starting point for solving it

- Reduction

- transforming the problem into another problem for which solutions exist

- Research

- employing existing ideas or adapting existing solutions to similar problems

- Root cause analysis

- identifying the cause of a problem

- Trial-and-error

- testing possible solutions until the right one is found

Problem-solving methods

[edit]- A3 problem solving – Structured problem improvement approach

- Design thinking – Processes by which design concepts are developed

- Eight Disciplines Problem Solving – Eight disciplines of team-oriented problem solving method

- GROW model – Method for goal setting and problem solving

- Help-seeking – Theory in psychology

- How to Solve It – Book by George Pólya

- Lateral thinking – Manner of solving problems

- OODA loop – Observe–orient–decide–act cycle

- PDCA – Iterative design and management method

- Root cause analysis – Method of identifying the fundamental causes of faults or problems

- RPR problem diagnosis

- TRIZ – Problem-solving tools

- Scientific method – is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science.

- Swarm intelligence – Collective behavior of decentralized, self-organized systems

- System dynamics – Study of non-linear complex systems

Common barriers

[edit]Common barriers to problem solving include mental constructs that impede an efficient search for solutions. Five of the most common identified by researchers are: confirmation bias, mental set, functional fixedness, unnecessary constraints, and irrelevant information.

Confirmation bias

[edit]Confirmation bias is an unintentional tendency to collect and use data which favors preconceived notions. Such notions may be incidental rather than motivated by important personal beliefs: the desire to be right may be sufficient motivation.[34]

Scientific and technical professionals also experience confirmation bias. One online experiment, for example, suggested that professionals within the field of psychological research are likely to view scientific studies that agree with their preconceived notions more favorably than clashing studies.[35] According to Raymond Nickerson, one can see the consequences of confirmation bias in real-life situations, which range in severity from inefficient government policies to genocide. Nickerson argued that those who killed people accused of witchcraft demonstrated confirmation bias with motivation.[36] Researcher Michael Allen found evidence for confirmation bias with motivation in school children who worked to manipulate their science experiments to produce favorable results.[37]

However, confirmation bias does not necessarily require motivation. In 1960, Peter Cathcart Wason conducted an experiment in which participants first viewed three numbers and then created a hypothesis in the form of a rule that could have been used to create that triplet of numbers. When testing their hypotheses, participants tended to only create additional triplets of numbers that would confirm their hypotheses, and tended not to create triplets that would negate or disprove their hypotheses.[38]

Mental set

[edit]Mental set is the inclination to re-use a previously successful solution, rather than search for new and better solutions. It is a reliance on habit.

It was first articulated by Abraham S. Luchins in the 1940s with his well-known water jug experiments.[39] Participants were asked to fill one jug with a specific amount of water by using other jugs with different maximum capacities. After Luchins gave a set of jug problems that could all be solved by a single technique, he then introduced a problem that could be solved by the same technique, but also by a novel and simpler method. His participants tended to use the accustomed technique, oblivious of the simpler alternative.[40] This was again demonstrated in Norman Maier's 1931 experiment, which challenged participants to solve a problem by using a familiar tool (pliers) in an unconventional manner. Participants were often unable to view the object in a way that strayed from its typical use, a type of mental set known as functional fixedness (see the following section).

Rigidly clinging to a mental set is called fixation, which can deepen to an obsession or preoccupation with attempted strategies that are repeatedly unsuccessful.[41] In the late 1990s, researcher Jennifer Wiley found that professional expertise in a field can create a mental set, perhaps leading to fixation.[41]

Groupthink, in which each individual takes on the mindset of the rest of the group, can produce and exacerbate mental set.[42] Social pressure leads to everybody thinking the same thing and reaching the same conclusions.

Functional fixedness

[edit]Functional fixedness is the tendency to view an object as having only one function, and to be unable to conceive of any novel use, as in the Maier pliers experiment described above. Functional fixedness is a specific form of mental set, and is one of the most common forms of cognitive bias in daily life.

As an example, imagine a man wants to kill a bug in his house, but the only thing at hand is a can of air freshener. He may start searching for something to kill the bug instead of squashing it with the can, thinking only of its main function of deodorizing.

Tim German and Clark Barrett describe this barrier: "subjects become 'fixed' on the design function of the objects, and problem solving suffers relative to control conditions in which the object's function is not demonstrated."[43] Their research found that young children's limited knowledge of an object's intended function reduces this barrier[44] Research has also discovered functional fixedness in educational contexts, as an obstacle to understanding: "functional fixedness may be found in learning concepts as well as in solving chemistry problems."[45]

There are several hypotheses in regards to how functional fixedness relates to problem solving.[46] It may waste time, delaying or entirely preventing the correct use of a tool.

Unnecessary constraints

[edit]Unnecessary constraints are arbitrary boundaries imposed unconsciously on the task at hand, which foreclose a productive avenue of solution. The solver may become fixated on only one type of solution, as if it were an inevitable requirement of the problem. Typically, this combines with mental set—clinging to a previously successful method.[47][page needed]

Visual problems can also produce mentally invented constraints.[48][page needed] A famous example is the dot problem: nine dots arranged in a three-by-three grid pattern must be connected by drawing four straight line segments, without lifting pen from paper or backtracking along a line. The subject typically assumes the pen must stay within the outer square of dots, but the solution requires lines continuing beyond this frame, and researchers have found a 0% solution rate within a brief allotted time.[49]

This problem has produced the expression "think outside the box".[50][page needed] Such problems are typically solved via a sudden insight which leaps over the mental barriers, often after long toil against them.[51] This can be difficult depending on how the subject has structured the problem in their mind, how they draw on past experiences, and how well they juggle this information in their working memory. In the example, envisioning the dots connected outside the framing square requires visualizing an unconventional arrangement, which is a strain on working memory.[50]

Irrelevant information

[edit]Irrelevant information is a specification or data presented in a problem that is unrelated to the solution.[47] If the solver assumes that all information presented needs to be used, this often derails the problem solving process, making relatively simple problems much harder.[52]

For example: "Fifteen percent of the people in Topeka have unlisted telephone numbers. You select 200 names at random from the Topeka phone book. How many of these people have unlisted phone numbers?"[50][page needed] The "obvious" answer is 15%, but in fact none of the unlisted people would be listed among the 200. This kind of "trick question" is often used in aptitude tests or cognitive evaluations.[53] Though not inherently difficult, they require independent thinking that is not necessarily common. Mathematical word problems often include irrelevant qualitative or numerical information as an extra challenge.

Avoiding barriers by changing problem representation

[edit]The disruption caused by the above cognitive biases can depend on how the information is represented:[53] visually, verbally, or mathematically. A classic example is the Buddhist monk problem:

A Buddhist monk begins at dawn one day walking up a mountain, reaches the top at sunset, meditates at the top for several days until one dawn when he begins to walk back to the foot of the mountain, which he reaches at sunset. Making no assumptions about his starting or stopping or about his pace during the trips, prove that there is a place on the path which he occupies at the same hour of the day on the two separate journeys.

The problem cannot be addressed in a verbal context, trying to describe the monk's progress on each day. It becomes much easier when the paragraph is represented mathematically by a function: one visualizes a graph whose horizontal axis is time of day, and whose vertical axis shows the monk's position (or altitude) on the path at each time. Superimposing the two journey curves, which traverse opposite diagonals of a rectangle, one sees they must cross each other somewhere. The visual representation by graphing has resolved the difficulty.

Similar strategies can often improve problem solving on tests.[47][54]

Other barriers for individuals

[edit]People who are engaged in problem solving tend to overlook subtractive changes, even those that are critical elements of efficient solutions. For example, a city planner may decide that the solution to decrease traffic congestion would be to add another lane to a highway, rather than finding ways to reduce the need for the highway in the first place. This tendency to solve by first, only, or mostly creating or adding elements, rather than by subtracting elements or processes is shown to intensify with higher cognitive loads such as information overload.[55]

Dreaming: problem solving without waking consciousness

[edit]People can also solve problems while they are asleep. There are many reports of scientists and engineers who solved problems in their dreams. For example, Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine, figured out the structure of the bobbin from a dream.[56]

The chemist August Kekulé was considering how benzene arranged its six carbon and hydrogen atoms. Thinking about the problem, he dozed off, and dreamt of dancing atoms that fell into a snakelike pattern, which led him to discover the benzene ring. As Kekulé wrote in his diary,

One of the snakes seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.[57]

There also are empirical studies of how people can think consciously about a problem before going to sleep, and then solve the problem with a dream image. Dream researcher William C. Dement told his undergraduate class of 500 students that he wanted them to think about an infinite series, whose first elements were OTTFF, to see if they could deduce the principle behind it and to say what the next elements of the series would be.[58][page needed] He asked them to think about this problem every night for 15 minutes before going to sleep and to write down any dreams that they then had. They were instructed to think about the problem again for 15 minutes when they awakened in the morning.

The sequence OTTFF is the first letters of the numbers: one, two, three, four, five. The next five elements of the series are SSENT (six, seven, eight, nine, ten). Some of the students solved the puzzle by reflecting on their dreams. One example was a student who reported the following dream:[58][page needed]

I was standing in an art gallery, looking at the paintings on the wall. As I walked down the hall, I began to count the paintings: one, two, three, four, five. As I came to the sixth and seventh, the paintings had been ripped from their frames. I stared at the empty frames with a peculiar feeling that some mystery was about to be solved. Suddenly I realized that the sixth and seventh spaces were the solution to the problem!

With more than 500 undergraduate students, 87 dreams were judged to be related to the problems students were assigned (53 directly related and 34 indirectly related). Yet of the people who had dreams that apparently solved the problem, only seven were actually able to consciously know the solution. The rest (46 out of 53) thought they did not know the solution.

Albert Einstein believed that much problem solving goes on unconsciously, and the person must then figure out and formulate consciously what the mindbrain[jargon] has already solved. He believed this was his process in formulating the theory of relativity: "The creator of the problem possesses the solution."[59] Einstein said that he did his problem solving without words, mostly in images. "The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be 'voluntarily' reproduced and combined."[60]

Cognitive sciences: two schools

[edit]Problem-solving processes differ across knowledge domains and across levels of expertise.[61] For this reason, cognitive sciences findings obtained in the laboratory cannot necessarily generalize to problem-solving situations outside the laboratory. This has led to a research emphasis on real-world problem solving, since the 1990s. This emphasis has been expressed quite differently in North America and Europe, however. Whereas North American research has typically concentrated on studying problem solving in separate, natural knowledge domains, much of the European research has focused on novel, complex problems, and has been performed with computerized scenarios.[62]

Europe

[edit]In Europe, two main approaches have surfaced, one initiated by Donald Broadbent[63] in the United Kingdom and the other one by Dietrich Dörner[64] in Germany. The two approaches share an emphasis on relatively complex, semantically rich, computerized laboratory tasks, constructed to resemble real-life problems. The approaches differ somewhat in their theoretical goals and methodology. The tradition initiated by Broadbent emphasizes the distinction between cognitive problem-solving processes that operate under awareness versus outside of awareness, and typically employs mathematically well-defined computerized systems. The tradition initiated by Dörner, on the other hand, has an interest in the interplay of the cognitive, motivational, and social components of problem solving, and utilizes very complex computerized scenarios that contain up to 2,000 highly interconnected variables.[65]

North America

[edit]In North America, initiated by the work of Herbert A. Simon on "learning by doing" in semantically rich domains,[66] researchers began to investigate problem solving separately in different natural knowledge domains—such as physics, writing, or chess playing—rather than attempt to extract a global theory of problem solving.[67] These researchers have focused on the development of problem solving within certain domains, that is on the development of expertise.[68]

Areas that have attracted rather intensive attention in North America include:

- calculation[69]

- computer skills[70]

- game playing[71]

- lawyers' reasoning[72]

- managerial problem solving[73]

- physical problem solving

- mathematical problem solving[74]

- mechanical problem solving[75]

- personal problem solving[76]

- political decision making[77]

- problem solving in electronics[78]

- problem solving for innovations and inventions: TRIZ[79]

- reading[80]

- social problem solving[11]

- writing[81]

Characteristics of complex problems

[edit]Complex problem solving (CPS) is distinguishable from simple problem solving (SPS). In SPS there is a singular and simple obstacle. In CPS there may be multiple simultaneous obstacles. For example, a surgeon at work has far more complex problems than an individual deciding what shoes to wear. As elucidated by Dietrich Dörner, and later expanded upon by Joachim Funke, complex problems have some typical characteristics, which include:[1]

- complexity (large numbers of items, interrelations, and decisions)

- enumerability[clarification needed]

- heterogeneity[specify]

- connectivity (hierarchy relation, communication relation, allocation relation)[clarification needed]

- dynamics (time considerations)[clarification needed]

- temporal constraints

- temporal sensitivity[clarification needed]

- phase effects[definition needed]

- dynamic unpredictability[specify]

- intransparency (lack of clarity of the situation)

- commencement opacity[definition needed]

- continuation opacity[definition needed]

- polytely (multiple goals)[82]

Collective problem solving

[edit]People solve problems on many different levels—from the individual to the civilizational. Collective problem solving refers to problem solving performed collectively. Social issues and global issues can typically only be solved collectively.

The complexity of contemporary problems exceeds the cognitive capacity of any individual and requires different but complementary varieties of expertise and collective problem solving ability.[83]

Collective intelligence is shared or group intelligence that emerges from the collaboration, collective efforts, and competition of many individuals.

In collaborative problem solving people work together to solve real-world problems. Members of problem-solving groups share a common concern, a similar passion, and/or a commitment to their work. Members can ask questions, wonder, and try to understand common issues. They share expertise, experiences, tools, and methods.[84] Groups may be fluid based on need, may only occur temporarily to finish an assigned task, or may be more permanent depending on the nature of the problems.

For example, in the educational context, members of a group may all have input into the decision-making process and a role in the learning process. Members may be responsible for the thinking, teaching, and monitoring of all members in the group. Group work may be coordinated among members so that each member makes an equal contribution to the whole work. Members can identify and build on their individual strengths so that everyone can make a significant contribution to the task.[85] Collaborative group work has the ability to promote critical thinking skills, problem solving skills, social skills, and self-esteem. By using collaboration and communication, members often learn from one another and construct meaningful knowledge that often leads to better learning outcomes than individual work.[86]

Collaborative groups require joint intellectual efforts between the members and involve social interactions to solve problems together. The knowledge shared during these interactions is acquired during communication, negotiation, and production of materials.[87] Members actively seek information from others by asking questions. The capacity to use questions to acquire new information increases understanding and the ability to solve problems.[88]

In a 1962 research report, Douglas Engelbart linked collective intelligence to organizational effectiveness, and predicted that proactively "augmenting human intellect" would yield a multiplier effect in group problem solving: "Three people working together in this augmented mode [would] seem to be more than three times as effective in solving a complex problem as is one augmented person working alone".[89]

Henry Jenkins, a theorist of new media and media convergence, draws on the theory that collective intelligence can be attributed to media convergence and participatory culture.[90] He criticizes contemporary education for failing to incorporate online trends of collective problem solving into the classroom, stating "whereas a collective intelligence community encourages ownership of work as a group, schools grade individuals". Jenkins argues that interaction within a knowledge community builds vital skills for young people, and teamwork through collective intelligence communities contributes to the development of such skills.[91]

Collective impact is the commitment of a group of actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem, using a structured form of collaboration.

After World War II the UN, the Bretton Woods organization, and the WTO were created. Collective problem solving on the international level crystallized around these three types of organization from the 1980s onward. As these global institutions remain state-like or state-centric it is unsurprising that they perpetuate state-like or state-centric approaches to collective problem solving rather than alternative ones.[92]

Crowdsourcing is a process of accumulating ideas, thoughts, or information from many independent participants, with aim of finding the best solution for a given challenge. Modern information technologies allow for many people to be involved and facilitate managing their suggestions in ways that provide good results.[93] The Internet allows for a new capacity of collective (including planetary-scale) problem solving.[94]

See also

[edit]- Actuarial science – Statistics applied to risk in insurance and other financial products

- Analytical skill – Crucial skill in all different fields of work and life

- Creative problem-solving – Mental process of problem solving

- Collective intelligence – Group intelligence that emerges from collective efforts

- Community of practice

- Coworking – Practice of independent contractors or scientists sharing office space without supervision

- Crowdsolving – Sourcing services or funds from a group

- Divergent thinking – Process of generating creative ideas

- Grey problem

- Innovation – Practical implementation of improvements

- Instrumentalism – Position in the philosophy of science

- Problem-posing education – Method of teaching coined by Paulo Freire

- Problem statement – Description of an issue

- Problem structuring methods

- Shared intentionality – Ability to engage with others' psychological states

- Structural fix

- Subgoal labeling – Cognitive process

- Troubleshooting – Form of problem solving, often applied to repair failed products or processes

- Wicked problem – Problem that is difficult or impossible to solve

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Frensch, Peter A.; Funke, Joachim, eds. (2014-04-04). Complex Problem Solving. Psychology Press. doi:10.4324/9781315806723. ISBN 978-1-315-80672-3.

- ^ a b Schacter, D.L.; Gilbert, D.T.; Wegner, D.M. (2011). Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. p. 376.

- ^ Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). "Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00469.x. S2CID 145645352.

- ^ Zimmermann, Bernd (2004). On mathematical problem-solving processes and history of mathematics. ICME 10. Copenhagen.

- ^ Granvold, Donald K. (1997). "Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Adults". In Brandell, Jerrold R. (ed.). Theory and Practice in Clinical Social Work. Simon and Schuster. pp. 189. ISBN 978-0-684-82765-0.

- ^ Robertson, S. Ian (2001). "Introduction to the study of problem solving". Problem Solving. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-415-20300-7.

- ^ Rubin, M.; Watt, S. E.; Ramelli, M. (2012). "Immigrants' social integration as a function of approach-avoidance orientation and problem-solving style". International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 36 (4): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.12.009. hdl:1959.13/931119.

- ^ Goldstein F. C.; Levin H. S. (1987). "Disorders of reasoning and problem-solving ability". In M. Meier; A. Benton; L. Diller (eds.). Neuropsychological rehabilitation. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- ^

- Vallacher, Robin; M. Wegner, Daniel (2012). "Action Identification Theory". Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. pp. 327–348. doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n17. ISBN 978-0-85702-960-7.

- Margrett, J. A; Marsiske, M (2002). "Gender differences in older adults' everyday cognitive collaboration". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 26 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1080/01650250143000319. PMC 2909137. PMID 20657668.

- Antonucci, T. C; Ajrouch, K. J; Birditt, K. S (2013). "The Convoy Model: Explaining Social Relations From a Multidisciplinary Perspective". The Gerontologist. 54 (1): 82–92. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt118. PMC 3894851. PMID 24142914.

- ^ Rath, Joseph F.; Simon, Dvorah; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Sherr, Rose Lynn; Diller, Leonard (2003). "Group treatment of problem-solving deficits in outpatients with traumatic brain injury: A randomised outcome study". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 13 (4): 461–488. doi:10.1080/09602010343000039. S2CID 143165070.

- ^ a b

- D'Zurilla, T. J.; Goldfried, M. R. (1971). "Problem solving and behavior modification". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 78 (1): 107–126. doi:10.1037/h0031360. PMID 4938262.

- D'Zurilla, T. J.; Nezu, A. M. (1982). "Social problem solving in adults". In P. C. Kendall (ed.). Advances in cognitive-behavioral research and therapy. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press. pp. 201–274.

- ^ Rath, J. F.; Langenbahn, D. M.; Simon, D; Sherr, R. L.; Fletcher, J.; Diller, L. (2004). "The construct of problem solving in higher level neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation*1". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 19 (5): 613–635. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2003.08.006. PMID 15271407.

- ^ Rath, Joseph F.; Hradil, Amy L.; Litke, David R.; Diller, Leonard (2011). "Clinical applications of problem-solving research in neuropsychological rehabilitation: Addressing the subjective experience of cognitive deficits in outpatients with acquired brain injury". Rehabilitation Psychology. 56 (4): 320–328. doi:10.1037/a0025817. ISSN 1939-1544. PMC 9728040. PMID 22121939.

- ^ Hoppmann, Christiane A.; Blanchard-Fields, Fredda (2010). "Goals and everyday problem solving: Manipulating goal preferences in young and older adults". Developmental Psychology. 46 (6): 1433–1443. doi:10.1037/a0020676. PMID 20873926.

- ^ Duncker, Karl (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- ^ Newell, Allen; Simon, Herbert A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ For example:

- X-ray problem, by Duncker, Karl (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- Disk problem, later known as Tower of Hanoi, by Ewert, P. H.; Lambert, J. F. (1932). "Part II: The Effect of Verbal Instructions upon the Formation of a Concept". The Journal of General Psychology. 6 (2). Informa UK Limited: 400–413. doi:10.1080/00221309.1932.9711880. ISSN 0022-1309. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-06-09.

- ^ Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition (Second ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ Armstrong, J. Scott; Denniston, William B. Jr.; Gordon, Matt M. (1975). "The Use of the Decomposition Principle in Making Judgments" (PDF). Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 14 (2): 257–263. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(75)90028-8. S2CID 122659209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-20.

- ^ Malakooti, Behnam (2013). Operations and Production Systems with Multiple Objectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-58537-5.

- ^ Kowalski, Robert (1974). "Predicate Logic as a Programming Language" (PDF). Information Processing. 74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Kowalski, Robert (1979). Logic for Problem Solving (PDF). Artificial Intelligence Series. Vol. 7. Elsevier Science Publishing. ISBN 0-444-00368-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-02. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Kowalski, Robert (2011). Computational Logic and Human Thinking: How to be Artificially Intelligent (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-06-01. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Staat, Wim (1993). "On abduction, deduction, induction and the categories". Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. 29 (2): 225–237.

- ^ Sullivan, Patrick F. (1991). "On Falsificationist Interpretations of Peirce". Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. 27 (2): 197–219.

- ^ Ho, Yu Chong (1994). Abduction? Deduction? Induction? Is There a Logic of Exploratory Data Analysis? (PDF). Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. New Orleans, La. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-02. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Passuello, Luciano (2008-11-04). "Einstein's Secret to Amazing Problem Solving (and 10 Specific Ways You Can Use It)". Litemind. Archived from the original on 2017-06-21. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ^ Tschisgale, Paul; Kubsch, Marcus; Wulff, Peter; Petersen, Stefan; Neumann, Knut (2025-01-31). "Exploring the sequential structure of students' physics problem-solving approaches using process mining and sequence analysis". Physical Review Physics Education Research. 21 (1). doi:10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.21.010111. ISSN 2469-9896.

- ^ a b c "Commander's Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy" (PDF). United States Joint Forces Command, Joint Warfighting Center, Suffolk, Va. 27 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b Robertson, S. Ian (2017). Problem solving: perspectives from cognition and neuroscience (2nd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-49601-4. OCLC 962750529.

- ^ Bransford, J. D.; Stein, B. S (1993). The ideal problem solver: A guide for improving thinking, learning, and creativity (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman.

- ^

- Ash, Ivan K.; Jee, Benjamin D.; Wiley, Jennifer (2012). "Investigating Insight as Sudden Learning". The Journal of Problem Solving. 4 (2). doi:10.7771/1932-6246.1123. ISSN 1932-6246.

- Chronicle, Edward P.; MacGregor, James N.; Ormerod, Thomas C. (2004). "What Makes an Insight Problem? The Roles of Heuristics, Goal Conception, and Solution Recoding in Knowledge-Lean Problems" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 30 (1): 14–27. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.14. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 14736293. S2CID 15631498.

- Chu, Yun; MacGregor, James N. (2011). "Human Performance on Insight Problem Solving: A Review". The Journal of Problem Solving. 3 (2). doi:10.7771/1932-6246.1094. ISSN 1932-6246.

- ^ Wang, Y.; Chiew, V. (2010). "On the cognitive process of human problem solving" (PDF). Cognitive Systems Research. 11 (1). Elsevier BV: 81–92. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2008.08.003. ISSN 1389-0417. S2CID 16238486.

- ^ Nickerson, Raymond S. (1998). "Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises". Review of General Psychology. 2 (2): 176. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175. S2CID 8508954.

- ^ Hergovich, Andreas; Schott, Reinhard; Burger, Christoph (2010). "Biased Evaluation of Abstracts Depending on Topic and Conclusion: Further Evidence of a Confirmation Bias Within Scientific Psychology". Current Psychology. 29 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 188–209. doi:10.1007/s12144-010-9087-5. ISSN 1046-1310. S2CID 145497196.

- ^ Nickerson, Raymond (1998). "Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises". Review of General Psychology. 2 (2). American Psychological Association: 175–220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

- ^ Allen, Michael (2011). "Theory-led confirmation bias and experimental persona". Research in Science & Technological Education. 29 (1). Informa UK Limited: 107–127. Bibcode:2011RSTEd..29..107A. doi:10.1080/02635143.2010.539973. ISSN 0263-5143. S2CID 145706148.

- ^ Wason, P. C. (1960). "On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 12 (3): 129–140. doi:10.1080/17470216008416717. S2CID 19237642.

- ^ Luchins, Abraham S. (1942). "Mechanization in problem solving: The effect of Einstellung". Psychological Monographs. 54 (248): i-95. doi:10.1037/h0093502.

- ^ Öllinger, Michael; Jones, Gary; Knoblich, Günther (2008). "Investigating the Effect of Mental Set on Insight Problem Solving" (PDF). Experimental Psychology. 55 (4). Hogrefe Publishing Group: 269–282. doi:10.1027/1618-3169.55.4.269. ISSN 1618-3169. PMID 18683624. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-16. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ a b Wiley, Jennifer (1998). "Expertise as mental set: The effects of domain knowledge in creative problem solving". Memory & Cognition. 24 (4): 716–730. doi:10.3758/bf03211392. PMID 9701964.

- ^ Cottam, Martha L.; Dietz-Uhler, Beth; Mastors, Elena; Preston, Thomas (2010). Introduction to Political Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press.

- ^ German, Tim P.; Barrett, H. Clark (2005). "Functional Fixedness in a Technologically Sparse Culture". Psychological Science. 16 (1). SAGE Publications: 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00771.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 15660843. S2CID 1833823.

- ^ German, Tim P.; Defeyter, Margaret A. (2000). "Immunity to functional fixedness in young children". Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 7 (4): 707–712. doi:10.3758/BF03213010. PMID 11206213.

- ^ Furio, C.; Calatayud, M. L.; Baracenas, S.; Padilla, O. (2000). "Functional fixedness and functional reduction as common sense reasonings in chemical equilibrium and in geometry and polarity of molecules". Science Education. 84 (5): 545–565. Bibcode:2000SciEd..84..545F. doi:10.1002/1098-237X(200009)84:5<545::AID-SCE1>3.0.CO;2-1.

- ^ Adamson, Robert E (1952). "Functional fixedness as related to problem solving: A repetition of three experiments". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 44 (4): 288–291. doi:10.1037/h0062487. PMID 13000071.

- ^ a b c Kellogg, R. T. (2003). Cognitive psychology (2nd ed.). California: Sage Publications, Inc.

- ^ Meloy, J. R. (1998). The Psychology of Stalking, Clinical and Forensic Perspectives (2nd ed.). London, England: Academic Press.

- ^ MacGregor, J.N.; Ormerod, T.C.; Chronicle, E.P. (2001). "Information-processing and insight: A process model of performance on the nine-dot and related problems". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 27 (1): 176–201. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.27.1.176. PMID 11204097.

- ^ a b c Weiten, Wayne (2011). Psychology: themes and variations (8th ed.). California: Wadsworth.

- ^ Novick, L. R.; Bassok, M. (2005). "Problem solving". In Holyoak, K. J.; Morrison, R. G. (eds.). Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 321–349.

- ^ Walinga, Jennifer (2010). "From walls to windows: Using barriers as pathways to insightful solutions". The Journal of Creative Behavior. 44 (3): 143–167. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2010.tb01331.x.

- ^ a b Walinga, Jennifer; Cunningham, J. Barton; MacGregor, James N. (2011). "Training insight problem solving through focus on barriers and assumptions". The Journal of Creative Behavior. 45: 47–58. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2011.tb01084.x.

- ^ Vlamings, Petra H. J. M.; Hare, Brian; Call, Joseph (2009). "Reaching around barriers: The performance of great apes and 3–5-year-old children". Animal Cognition. 13 (2): 273–285. doi:10.1007/s10071-009-0265-5. PMC 2822225. PMID 19653018.

- ^

- Gupta, Sujata (7 April 2021). "People add by default even when subtraction makes more sense". Science News. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- Adams, Gabrielle S.; Converse, Benjamin A.; Hales, Andrew H.; Klotz, Leidy E. (April 2021). "People systematically overlook subtractive changes". Nature. 592 (7853): 258–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..258A. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03380-y. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33828317. S2CID 233185662. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Kaempffert, Waldemar B. (1924). A Popular History of American Invention. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 385.

- ^

- Kekulé, August (1890). "Benzolfest-Rede". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 23: 1302–1311.

- Benfey, O. (1958). "Kekulé and the birth of the structural theory of organic chemistry in 1858". Journal of Chemical Education. 35 (1): 21–23. Bibcode:1958JChEd..35...21B. doi:10.1021/ed035p21.

- ^ a b Dement, W.C. (1972). Some Must Watch While Some Just Sleep. New York: Freeman.

- ^ Fromm, Erika O. (1998). "Lost and found half a century later: Letters by Freud and Einstein". American Psychologist. 53 (11): 1195–1198. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.53.11.1195.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1954). "A Mathematician's Mind". Ideas and Opinions. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 25.

- ^ Sternberg, R. J. (1995). "Conceptions of expertise in complex problem solving: A comparison of alternative conceptions". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 295–321.

- ^ Funke, J. (1991). "Solving complex problems: Human identification and control of complex systems". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 185–222. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^

- Broadbent, Donald E. (1977). "Levels, hierarchies, and the locus of control". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 29 (2): 181–201. doi:10.1080/14640747708400596. S2CID 144328372. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-06-09.

- Berry, Dianne C.; Broadbent, Donald E. (1995). "Implicit learning in the control of complex systems: A reconsideration of some of the earlier claims". In Frensch, P.A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 131–150.

- ^

- Dörner, Dietrich (1975). "Wie Menschen eine Welt verbessern wollten" [How people wanted to improve the world]. Bild der Wissenschaft (in German). 12: 48–53.

- Dörner, Dietrich (1985). "Verhalten, Denken und Emotionen" [Behavior, thinking, and emotions]. In Eckensberger, L. H.; Lantermann, E. D. (eds.). Emotion und Reflexivität (in German). München, Germany: Urban & Schwarzenberg. pp. 157–181.

- Dörner, Dietrich; Wearing, Alex J. (1995). "Complex problem solving: Toward a (computer-simulated) theory". In Frensch, P.A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 65–99.

- ^

- Buchner, A. (1995). "Theories of complex problem solving". In Frensch, P.A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 27–63.

- Dörner, D.; Kreuzig, H. W.; Reither, F.; Stäudel, T., eds. (1983). Lohhausen. Vom Umgang mit Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität [Lohhausen. On dealing with uncertainty and complexity] (in German). Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber.

- Ringelband, O. J.; Misiak, C.; Kluwe, R. H. (1990). "Mental models and strategies in the control of a complex system". In Ackermann, D.; Tauber, M. J. (eds.). Mental models and human-computer interaction. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. pp. 151–164.

- ^

- Anzai, K.; Simon, H. A. (1979). "The theory of learning by doing". Psychological Review. 86 (2): 124–140. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.86.2.124. PMID 493441.

- Bhaskar, R.; Simon, Herbert A. (1977). "Problem Solving in Semantically Rich Domains: An Example from Engineering Thermodynamics". Cognitive Science. 1 (2). Wiley: 193–215. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog0102_3. ISSN 0364-0213.

- ^ e.g., Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A., eds. (1991). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^

- Chase, W. G.; Simon, H. A. (1973). "Perception in chess". Cognitive Psychology. 4: 55–81. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(73)90004-2.

- Chi, M. T. H.; Feltovich, P. J.; Glaser, R. (1981). "Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices". Cognitive Science. 5 (2): 121–152. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog0502_2.

- Anderson, J. R.; Boyle, C. B.; Reiser, B. J. (1985). "Intelligent tutoring systems". Science. 228 (4698): 456–462. Bibcode:1985Sci...228..456A. doi:10.1126/science.228.4698.456. PMID 17746875. S2CID 62403455.

- ^ Sokol, S. M.; McCloskey, M. (1991). "Cognitive mechanisms in calculation". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 85–116. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Kay, D. S. (1991). "Computer interaction: Debugging the problems". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 317–340. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Frensch, P. A.; Sternberg, R. J. (1991). "Skill-related differences in game playing". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J .: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 343–381. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Amsel, E.; Langer, R.; Loutzenhiser, L. (1991). "Do lawyers reason differently from psychologists? A comparative design for studying expertise". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 223–250. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Wagner, R. K. (1991). "Managerial problem solving". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 159–183. PsycNET: 1991-98396-005.

- ^

- Pólya, George (1945). How to Solve It. Princeton University Press.

- Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical Problem Solving. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-9548-0. Archived from the original on 2023-10-23. Retrieved 2019-06-09.

- ^ Hegarty, M. (1991). "Knowledge and processes in mechanical problem solving". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 253–285. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Heppner, P. P.; Krauskopf, C. J. (1987). "An information-processing approach to personal problem solving". The Counseling Psychologist. 15 (3): 371–447. doi:10.1177/0011000087153001. S2CID 146180007.

- ^ Voss, J. F.; Wolfe, C. R.; Lawrence, J. A.; Engle, R. A. (1991). "From representation to decision: An analysis of problem solving in international relations". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 119–158. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. PsycNET: 1991-98396-004.

- ^ Lesgold, A.; Lajoie, S. (1991). "Complex problem solving in electronics". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 287–316. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Altshuller, Genrich (1994). And Suddenly the Inventor Appeared. Translated by Lev Shulyak. Worcester, Mass.: Technical Innovation Center. ISBN 978-0-9640740-1-9.

- ^ Stanovich, K. E.; Cunningham, A. E. (1991). "Reading as constrained reasoning". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 3–60. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. Archived from the original on 2023-09-03. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Bryson, M.; Bereiter, C.; Scardamalia, M.; Joram, E. (1991). "Going beyond the problem as given: Problem solving in expert and novice writers". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 61–84. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A., eds. (1991). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Hung, Woei (2013). "Team-based complex problem solving: a collective cognition perspective". Educational Technology Research and Development. 61 (3): 365–384. doi:10.1007/s11423-013-9296-3. S2CID 62663840.

- ^ Jewett, Pamela; MacPhee, Deborah (2012). "Adding Collaborative Peer Coaching to Our Teaching Identities". The Reading Teacher. 66 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1002/TRTR.01089.

- ^ Wang, Qiyun (2009). "Design and Evaluation of a Collaborative Learning Environment". Computers and Education. 53 (4): 1138–1146. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.05.023.

- ^ Wang, Qiyan (2010). "Using online shared workspaces to support group collaborative learning". Computers and Education. 55 (3): 1270–1276. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.023.

- ^ Kai-Wai Chu, Samuel; Kennedy, David M. (2011). "Using Online Collaborative tools for groups to Co-Construct Knowledge". Online Information Review. 35 (4): 581–597. doi:10.1108/14684521111161945. ISSN 1468-4527. S2CID 206388086.

- ^ Legare, Cristine; Mills, Candice; Souza, Andre; Plummer, Leigh; Yasskin, Rebecca (2013). "The use of questions as problem-solving strategies during early childhood". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 114 (1): 63–7. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2012.07.002. PMID 23044374.

- ^ Engelbart, Douglas (1962). "Team Cooperation". Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Vol. AFOSR-3223. Stanford Research Institute.

- ^ Flew, Terry (2008). New Media: an introduction. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Henry, Jenkins. "Interactive audiences? The 'collective intelligence' of media fans" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Finger, Matthias (2008-03-27). "Which governance for sustainable development? An organizational and institutional perspective". In Park, Jacob; Conca, Ken; Finger, Matthias (eds.). The Crisis of Global Environmental Governance: Towards a New Political Economy of Sustainability. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-134-05982-9.

- ^

- Guazzini, Andrea; Vilone, Daniele; Donati, Camillo; Nardi, Annalisa; Levnajić, Zoran (10 November 2015). "Modeling crowdsourcing as collective problem solving". Scientific Reports. 5 16557. arXiv:1506.09155. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516557G. doi:10.1038/srep16557. PMC 4639727. PMID 26552943.

- Boroomand, A.; Smaldino, P.E. (2021). "Hard Work, Risk-Taking, and Diversity in a Model of Collective Problem Solving". Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 24 (4) 10. doi:10.18564/jasss.4704. S2CID 240483312.

- ^ Stefanovitch, Nicolas; Alshamsi, Aamena; Cebrian, Manuel; Rahwan, Iyad (30 September 2014). "Error and attack tolerance of collective problem solving: The DARPA Shredder Challenge". EPJ Data Science. 3 (1) 13. doi:10.1140/epjds/s13688-014-0013-1. hdl:21.11116/0000-0002-D39F-D.

Further reading

[edit]- Beckmann, Jens F.; Guthke, Jürgen (1995). "Complex problem solving, intelligence, and learning ability". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 177–200.

- Brehmer, Berndt (1995). "Feedback delays in dynamic decision making". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 103–130.

- Brehmer, Berndt; Dörner, D. (1993). "Experiments with computer-simulated microworlds: Escaping both the narrow straits of the laboratory and the deep blue sea of the field study". Computers in Human Behavior. 9 (2–3): 171–184. doi:10.1016/0747-5632(93)90005-D.

- Dörner, D. (1992). "Über die Philosophie der Verwendung von Mikrowelten oder 'Computerszenarios' in der psychologischen Forschung" [On the proper use of microworlds or "computer scenarios" in psychological research]. In Gundlach, H. (ed.). Psychologische Forschung und Methode: Das Versprechen des Experiments. Festschrift für Werner Traxel (in German). Passau, Germany: Passavia-Universitäts-Verlag. pp. 53–87.

- Eyferth, K.; Schömann, M.; Widowski, D. (1986). "Der Umgang von Psychologen mit Komplexität" [On how psychologists deal with complexity]. Sprache & Kognition (in German). 5: 11–26.

- Funke, Joachim (1993). "Microworlds based on linear equation systems: A new approach to complex problem solving and experimental results" (PDF). In Strube, G.; Wender, K.-F. (eds.). The cognitive psychology of knowledge. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. pp. 313–330.

- Funke, Joachim (1995). "Experimental research on complex problem solving" (PDF). In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 243–268.

- Funke, U. (1995). "Complex problem solving in personnel selection and training". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 219–240.

- Groner, M.; Groner, R.; Bischof, W. F. (1983). "Approaches to heuristics: A historical review". In Groner, R.; Groner, M.; Bischof, W. F. (eds.). Methods of heuristics. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 1–18.

- Hayes, J. (1980). The complete problem solver. Philadelphia: The Franklin Institute Press.

- Huber, O. (1995). "Complex problem solving as multistage decision making". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 151–173.

- Hübner, Ronald (1989). "Methoden zur Analyse und Konstruktion von Aufgaben zur kognitiven Steuerung dynamischer Systeme" [Methods for the analysis and construction of dynamic system control tasks] (PDF). Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie (in German). 36: 221–238.

- Hunt, Earl (1991). "Some comments on the study of complexity". In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 383–395. ISBN 978-1-317-78386-2.

- Hussy, W. (1985). "Komplexes Problemlösen—Eine Sackgasse?" [Complex problem solving—a dead end?]. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie (in German). 32: 55–77.

- Kluwe, R. H. (1993). "Chapter 19 Knowledge and Performance in Complex Problem Solving". The Cognitive Psychology of Knowledge. Advances in Psychology. Vol. 101. pp. 401–423. doi:10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62668-0. ISBN 978-0-444-89942-2.

- Kluwe, R. H. (1995). "Single case studies and models of complex problem solving". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 269–291.

- Kolb, S.; Petzing, F.; Stumpf, S. (1992). "Komplexes Problemlösen: Bestimmung der Problemlösegüte von Probanden mittels Verfahren des Operations Research—ein interdisziplinärer Ansatz" [Complex problem solving: determining the quality of human problem solving by operations research tools—an interdisciplinary approach]. Sprache & Kognition (in German). 11: 115–128.

- Krems, Josef F. (1995). "Cognitive flexibility and complex problem solving". In Frensch, P. A.; Funke, J. (eds.). Complex problem solving: The European Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 201–218.

- Melzak, Z. (1983). Bypasses: A Simple Approach to Complexity. London, UK: Wiley.

- Müller, H. (1993). Komplexes Problemlösen: Reliabilität und Wissen [Complex problem solving: Reliability and knowledge] (in German). Bonn, Germany: Holos.

- Paradies, M.W.; Unger, L. W. (2000). TapRooT—The System for Root Cause Analysis, Problem Investigation, and Proactive Improvement. Knoxville, Tenn.: System Improvements.

- Putz-Osterloh, Wiebke (1993). "Chapter 15 Strategies for Knowledge Acquisition and Transfer of Knowledge in Dynamic Tasks". The Cognitive Psychology of Knowledge. Advances in Psychology. Vol. 101. pp. 331–350. doi:10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62664-3. ISBN 978-0-444-89942-2.

- Riefer, David M.; Batchelder, William H. (1988). "Multinomial modeling and the measurement of cognitive processes" (PDF). Psychological Review. 95 (3): 318–339. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.95.3.318. S2CID 14994393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-25.

- Schaub, H. (1993). Modellierung der Handlungsorganisation (in German). Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber.

- Strauß, B. (1993). Konfundierungen beim Komplexen Problemlösen. Zum Einfluß des Anteils der richtigen Lösungen (ArL) auf das Problemlöseverhalten in komplexen Situationen [Confoundations in complex problem solving. On the influence of the degree of correct solutions on problem solving in complex situations] (in German). Bonn, Germany: Holos.

- Strohschneider, S. (1991). "Kein System von Systemen! Kommentar zu dem Aufsatz 'Systemmerkmale als Determinanten des Umgangs mit dynamischen Systemen' von Joachim Funke" [No system of systems! Reply to the paper 'System features as determinants of behavior in dynamic task environments' by Joachim Funke]. Sprache & Kognition (in German). 10: 109–113.

- Tonelli, Marcello (2011). Unstructured Processes of Strategic Decision-Making. Saarbrücken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3-8465-5598-9.

- Van Lehn, Kurt (1989). "Problem solving and cognitive skill acquisition". In Posner, M. I. (ed.). Foundations of cognitive science (PDF). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. pp. 527–579.

- Wisconsin Educational Media Association (1993), Information literacy: A position paper on information problem-solving, WEMA Publications, vol. ED 376 817, Madison, Wis.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (Portions adapted from Michigan State Board of Education's Position Paper on Information Processing Skills, 1992.)

External links

[edit] Learning materials related to Solving Problems at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Solving Problems at Wikiversity

Problem solving

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Foundations

Core Definition and Distinctions

Problem solving constitutes the cognitive processes by which individuals or systems direct efforts toward attaining a goal absent an immediately known solution method.[11] This entails recognizing a gap between the existing state and the target outcome, then deploying mental operations—such as trial-and-error, analogy, or systematic search—to mitigate that discrepancy and reach resolution.[4] Empirical studies in cognitive psychology underscore that effective problem solving hinges on representing the problem accurately in working memory, evaluating feasible actions, and iterating based on feedback from intermediate states.[12] A primary distinction within problem solving concerns the problem's structure: well-defined problems provide explicit initial conditions, unambiguous goals, and permissible operators, enabling algorithmic resolution, as exemplified by chess moves under fixed rules or arithmetic computations.[13] Ill-defined problems, conversely, feature incomplete specifications—such as vague objectives or undefined constraints—necessitating initial efforts to refine the problem formulation itself, common in domains like urban planning or scientific hypothesis testing where multiple viable interpretations exist.[14] This dichotomy influences solution efficacy, with well-defined cases often yielding faster, more reliable outcomes via forward search, while ill-defined ones demand heuristic strategies and creative restructuring to avoid fixation on suboptimal paths.[15] Problem solving further differentiates from routine procedures, which invoke pre-learned scripts or automated responses for familiar scenarios without necessitating novel cognition, such as habitual route navigation.[16] In contrast, genuine problem solving arises when routines falter, requiring adaptive reasoning to devise non-standard interventions. It also contrasts with decision making, the latter entailing evaluation and selection among extant options to optimize outcomes under constraints, whereas problem solving precedes this by generating or identifying viable alternatives to address root discrepancies.[18][19] These boundaries highlight problem solving's emphasis on causal intervention over mere choice, grounded in first-principles analysis of state transitions rather than probabilistic selection.[20]Psychological and Cognitive Perspectives

Psychological perspectives on problem solving emphasize mental processes over observable behaviors, viewing it as a cognitive activity involving representation, search, and transformation of problem states. In Gestalt psychology, Wolfgang Köhler's experiments with chimpanzees in the 1910s demonstrated insight, where solutions emerged suddenly through restructuring the perceptual field rather than trial-and-error. For instance, chimps stacked boxes to reach bananas, indicating cognitive reorganization beyond incremental learning.[21][22] The information-processing approach, advanced by Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon in the 1950s, models problem solving as searching a problem space defined by initial states, goal states, and operators. Their General Problem Solver (GPS) program, implemented in 1959, used means-ends analysis to reduce differences between current and goal states via heuristic steps. This framework posits humans as symbol manipulators akin to computers, supported by protocols from tasks like the Tower of Hanoi.[23][24] Cognitive strategies distinguish algorithms, which guarantee solutions through exhaustive enumeration like breadth-first search, from heuristics, efficient shortcuts such as hill-climbing or analogy that risk suboptimal outcomes but save computational resources. Heuristics like availability bias influence real-world decisions, as evidenced in Tversky and Kahneman's 1974 studies on judgment under uncertainty. Functional fixedness, identified by Karl Duncker in 1945, exemplifies barriers where objects are perceived only in accustomed uses, impeding novel applications.[25][26] Graham Wallas's 1926 model outlines four stages: preparation (gathering information), incubation (unconscious processing), illumination (aha moment), and verification (testing the solution). Empirical support includes studies showing incubation aids insight after breaks from fixation, though mechanisms remain debated, with neural imaging suggesting default mode network activation during incubation. Mental sets, preconceived solution patterns, further constrain flexibility, as replicated in Einstellung effect experiments where familiar strategies block superior alternatives.[27][4][28]Computational and Logical Frameworks

In computational models of problem solving, problems are represented as searches through a state space, comprising initial states, goal states, operators for state transitions, and path costs.[29] This paradigm originated with Allen Newell, Herbert A. Simon, and J.C. Shaw's General Problem Solver (GPS) program, implemented in 1957 at RAND Corporation, which automated theorem proving by mimicking human means-ends analysis: it identified discrepancies between current and target states, selected operators to minimize differences, and recursively applied subgoals.[30] GPS's success in solving logic puzzles and proofs validated computational simulation of cognition, though limited by exponential search complexity in large spaces.[31] Uninformed search algorithms systematically explore state spaces without goal-specific guidance; breadth-first search (BFS) expands nodes level by level, ensuring shortest-path optimality for uniform costs but requiring significant memory, while depth-first search (DFS) prioritizes depth via stack-based recursion, conserving memory at the risk of incomplete exploration in infinite spaces.[32] Informed methods enhance efficiency with heuristics; the A* algorithm, formulated in 1968 by Peter Hart, Nils Nilsson, and Bertram Raphael, evaluates nodes by f(n) = g(n) + h(n), where g(n) is path cost from start and h(n) is admissible heuristic estimate to goal, guaranteeing optimality if h(n) never overestimates.[32] These techniques underpin AI planning and optimization, scaling via pruning and approximations for real-world applications like route finding.[32] Logical frameworks formalize problem solving through deductive inference in symbolic systems, encoding knowledge in propositional or first-order logic and deriving solutions via sound proof procedures.[33] Automated reasoning tools apply resolution or tableaux methods to check satisfiability or entailment; for instance, SAT solvers like MiniSat, evolving from Davis-Putnam-Logemann-Loveland procedure (1962), efficiently decide propositional formulas under NP-completeness by clause learning and unit propagation.[33] Constraint satisfaction problems (CSPs) model combinatorial tasks—such as scheduling or map coloring—as variable domains with binary or global constraints, solved by backtracking search augmented with arc consistency to prune inconsistent partial assignments.[34] Logic programming paradigms, exemplified by Prolog (developed 1972 by Alain Colmerauer), declare problems as Horn clauses—facts and rules—enabling declarative solving via SLD-resolution and backward chaining, where queries unify with knowledge bases to generate proofs as computations.[35] Prolog's built-in search handles puzzles like the eight queens by implicit depth-first traversal with automatic backtracking on failures, though practical limits arise from left-recursion and lack of tabling without extensions.[36] These frameworks prioritize completeness and soundness, contrasting heuristic searches, but demand precise formalization to avoid undecidability in expressive logics.[33]Engineering and Practical Applications