Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Catiline

View on WikipediaLucius Sergius Catilina (c. 108 BC – January 62 BC), known in English as Catiline (/ˈkætəlaɪn/), was a Roman politician and soldier best known for instigating the Catilinarian conspiracy, a failed attempt to seize control of the Roman state in 63 BC.

Key Information

Born to an ancient patrician family, he joined Sulla during Sulla's civil war and profited from Sulla's purges of his political enemies, becoming a wealthy man. In the early 60s BC, he served as praetor and then as governor of Africa (67–66 BC). Upon his return to Rome, he attempted to stand for the consulship but was rebuffed; he then was beset with legal challenges over alleged corruption in Africa and his actions during Sulla's proscriptions (83–82 BC). Acquitted on all charges with the support of influential friends in Roman politics, he stood for the consulship in 64 and in 63 BC.

Defeated in the consular comitia, he concocted a plot to take the consulship by force, bringing together poor rural plebs, Sullan veterans, and other senators whose political careers had stalled. Crassus revealed the coup attempt – which involved armed uprisings in Etruria – to Cicero, one of the consuls, in October 63 BC, but it took until November before evidence of Catiline's participation emerged. Discovered, he left the city to join his rebellion. In early January 62 BC, at the head of a rebel army near Pistoria (modern-day Pistoia in Tuscany), Catiline fought the Battle of Pistoria against republican forces. He was killed and his army annihilated.

Catiline's name became a byword for doomed and treasonous rebellion in the years after his death. Sallust, in his monograph on the conspiracy, Bellum Catilinae, painted Catiline as a symbol of the Roman Republic's moral decline, as much of a victim as a perpetrator, as his characterization of "a ravaged mind" (vastus animus) indicates.[1][page needed]

Early life

[edit]Family background

[edit]Catiline was a member of an ancient patrician family, the gens Sergia, who claimed descent from Sergestus, a Trojan companion of Aeneas.[2] While Sallust says he was one of the nobiles,[3] which implies a consular heritage,[4] the specifics are unclear: no member of the gens Sergia had held the consulship since the second consulship of Gnaeus Sergius Fidenas Coxo in 429 BC; a few other Sergii had served in the consular tribunate, but the last was in 380 BC.[5]

The exact year of Catiline's birth is unknown. From the offices he held it can be deduced that he was born no later than 108 BC, or 106 BC if patricians enjoyed a right to hold magistracies two years earlier than plebeians.[2] Catiline's parents were Lucius Sergius Silus and Belliena.[6] His father was poor by the standards of the aristocracy.[7] His maternal uncle had served as praetor in 105 BC; earlier, Catiline's great-grandfather – Marcus Sergius Silus – had served with distinction as praetor in 197 BC during the Second Punic War.[8]

Early career

[edit]During the Social War, Catiline served under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, along with Strabo's son – the more famous Pompey – and Cicero.[9] His specific title was not recorded.[10] This is recorded on the Asculum Inscription, a bronze tablet which was once nailed to the wall of an unknown public building in Rome, which records the names of Pompeius Strabo's council (consilium) when he granted citizenship to several auxiliaries in his army; a Lucius Sergius is mentioned there, almost certainly Catiline.[11]

He married a woman named Gratidia, one of Gaius Marius's nieces.[12] During Sulla's civil war, Catiline joined with the Sullans in 82 BC and served as a lieutenant.[13] According to many of the ancient sources, he made himself wealthy during the Sullan proscriptions by killing his brother and two of his brothers-in-law (one brother of his wife and one husband of his sister).[14] Cicero accused him of helping Quintus Lutatius Catulus avenge himself upon Catiline's wife's brother, Marcus Marius Gratidianus, the prosecutor who had caused the death of Catulus' father.[15] Cicero's account – given in a campaign speech attacking Catiline, who was a rival candidate for the consulship of 63 BC, – has Catiline beheading Gratidianus and then carrying the head through the city from the Janiculum to Sulla at the Temple of Apollo; later accounts embellish the tale, describing Catiline as engaging in gratuitous cruelties against Gratidianus, as described in later sources such as Livy, Valerius Maximus, Lucan, and Florus.[16] Some modern historians doubt Catiline was involved in Gratidianus' death except perhaps in an auxiliary role, placing blame instead on Catulus and attributing the story of Catiline's involvement to Ciceronean political slander.[17] Regardless, Catiline did engage in profiteering from the Sullan proscriptions, likely purchasing estates for fractions of their true value, and by the end of Sulla's dictatorship, he had become a rich man.[18]

In 73 BC, he may have been prosecuted for adultery – apud pontifices (before a panel of pontiffs as judges) – with a Vestal Virgin named Fabia, a half-sister of Cicero's wife Terentia. While evidence for Fabia's prosecution is clear, only Orosius mentions Catiline's prosecution.[19] Conviction would have led to execution for sacrilege. Catiline's friend Catulus – probably the president of the court and definitely one of the pontiffs – and other former consuls rallied to help Fabia, and possibly Catiline if he too was prosecuted, securing their acquittals.[20] Catiline and Cicero "must have been relieved"; Catiline, for his part, regarded himself in Catulus' debt.[21]

Attempts at the consulship

[edit]Catiline served as praetor some time before 68 BC; T. R. S. Broughton in Magistrates of the Roman Republic dates the praetorship exactly to 68 BC.[22] He then served as propraetorian governor of Africa for two years (67–66 BC).[23]

Some time in the mid-60s BC, Catiline married the wealthy and beautiful Aurelia Orestilla, daughter of the consul of 71 BC, Gnaeus Aufidius Orestes; this was his second marriage.[24][25] Sallust relates that he did so not out of money, but only due to her good looks, something which Romans believed to be discreditable.[26] Cicero later claimed in his Catilinarians that Catiline murdered his first wife and Orestilla's son to make way for the match; he also claimed in In Toga Candida that Orestilla was Catiline's own illegitimate daughter. Cicero's allegations "cannot be taken at face value and reveal more about typical themes and slanders found in Roman invective than they do about Catiline's domestic history".[27]

Elections of 66 BC and trial

[edit]Upon his return to Rome in 66 BC, embassies from Africa protested his maladministration.[28] Catiline also attempted to stand for the consulship, but his candidacy was rejected by the presiding magistrate. Sallust and Cicero attribute the rejection to an imminent extortion trial,[29][30] but this decision may have been made in terms of the contested elections for the consulship of 65 BC: before Catiline's return to Rome, the first consular elections were held but both men elected[a] were deposed after they were both convicted of bribery; the second elections, after Catiline's return, were held with the same candidates – the two convicts excepted – returning two different consuls. Catiline's candidacy could have been rejected not due to expectations of an extortion trial, but rather for the mere fact that he was not a candidate in the first election.[32]

Following the elections, early in 65 BC, the ancient sources give contradictory descriptions of what is called a "First Catilinarian conspiracy" in which Catiline (except in Suetonius' narrative) conspired with the deposed consular candidates from the first election to recover the consulship by force. In some tellings, Catiline himself was to assume the consulship. Regardless, the supposed date of this alleged conspiracy, 5 February, came and went without incident.[33] Modern scholars overwhelmingly believe that this "First Catilinarian conspiracy" is fictitious.[34][35][36][37]

Later that year, in the second half of 65 BC (some time after 17 July), Catiline was brought to trial for corruption during his governorship. The prosecution was led by Publius Clodius Pulcher, but Catiline was defended by many influential former consuls, including one of the consuls of 65 BC (who had won in the second election; that consul also disavowed Catiline's rumoured involvement in the alleged putsch).[38] Clodius, prosecuting, may have helped Catiline out by selecting a favourable jury that would be impressed by the consulares coming to Catiline's aid.[39] But scholarly opinion on whether Clodius purposefully manipulated the proceedings for acquittal is divided.[40] In the end, the jury – composed of senators, equites, and the tribuni aerarii – divided: the senators voted for conviction, the latter two panels for acquittal. Cicero, not yet having broken with Catiline, considered defending Catiline at this trial,[41] but eventually decided not to; Catiline's advocate is unknown.[42]

Consular elections of 64 BC

[edit]Catiline's candidacy at the consular elections in 64 BC was accepted. Also standing for the consulship that year were Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida; the three were the only candidates with a realistic chance of winning.[43] Catiline, bankrolled by Caesar and Crassus, distributed large bribes; after a bill against electoral bribery was defeated, Cicero gave In toga candida, a speech full of invective attacking Catiline and Antonius.[44] Antonius and Catiline were allies during the election and attempted to beat Cicero. Their strategy, however, was unsuccessful. Cicero was carried unanimously and Antonius narrowly defeated Catiline.[45]

This was also the year that Gaius Julius Caesar was president of the standing court on assassinations. His willingness – along with Cato the Younger in the treasury demanding repayment of loans from the civil wars – to pursue the beneficiaries of the Sullan civil war may have swayed voters away from supporting Catiline.[43] This may also have been reinforced by timely conviction of Catiline's maternal uncle on charges of murder during the proscriptions.[45] After the consular elections, Catiline was brought up on charges of murdering people during the proscriptions, perhaps of Gratidianus. Prosecuted by Lucius Lucceius or possibly Caesar, Catiline was again acquitted when a number of former consuls spoke in his defence.[46] There is no evidence that Caesar affected Catiline's acquittal.[47]

Catilinarian conspiracy

[edit]

Antonius, Catiline's ally in the elections of 64 BC, joined with Cicero in a deal where he would take the wealthy and exploitable province of Macedonia (which Cicero had been given) in exchange for cooperation; he therefore broke with Catiline early in the year.[45] In early 63 BC, there were no indications that Catiline was involved in a conspiracy. He was still, however, nursing hopes of an eventual consulship that would be both his birth-right and necessary for his career.

Consular elections

[edit]

The events of the year 63 BC were not amenable for civil harmony, no matter how much Cicero as consul had been preaching it to the people. Early in the year, a proposal came before the plebs to redistribute lands; it was a proposal that would have alleviated great hardship in a time of economic hardship.[49] Cicero spoke out against it, warning of tyrannical land commissioners and painting the project as selling out the people to the beneficiaries of the Sullan proscriptions.[50] The failure of the land proposal contributed to the conspiracy's support among the people in the coming months.[51]

A trial that year for one Gaius Rabirius for the murder of Lucius Appuleius Saturninus in 100 BC, almost forty years earlier, was possibly a signal from Caesar to the senate against use of the senatus consultum ultimum (a declaration of emergency which gave the consuls political cover to break laws in suppressing civil unrest).[52] Rabirius was convicted by Caesar ("not an impartial judge") by means of an archaic procedure before appealing and then being acquitted by a similarly archaic loophole.[52] A later proposal to overturn Sulla's civil disabilities for the sons of the victims of the proscriptions also was defeated with Cicero's help; Cicero argued that repeal would cause political upheaval. This failure "drove some of the men concerned into supporting Catiline" in his conspiracy.[53]

That summer, Catiline stood again for the consulship for 62 BC; his candidacy was accepted by Cicero. Against him were three other major candidates: Decimus Junius Silanus, Lucius Licinius Murena, and Servius Sulpicius Rufus. Cicero supported Sulpicius' bid as a friend and fellow lawyer, which directly harmed Catiline's chances, since both men were patricians and therefore were legally barred from both holding the consulship.[54] Bribery was again rampant, after the senate moved again to pass legislation to stamp it out, Cicero and Antonius as consuls were successful in moving the lex Tullia increasing penalties and enumerating forbidden electoral practices.[55]

Just before the elections, Cicero alleges Catiline engaged in demagoguery and attempted to build up his bona fides with the poor and dispossessed men of Rome and Italy, including himself among their number,[56] advocating the wholesale abolition of all existing debts (tabulae novae).[57]

At the electoral comitia, Cicero presided, surrounded by a bodyguard and wearing an ostentatious cuirass, to signal his belief that Catiline posed a threat to his person and public safety.[58] Sallust reports that Catiline promised his supporters that he would kill the rich, but this supposed promise is likely ahistorical.[59] No contemporary source indicates that Catiline supported land reform.[60] The comitia returned as consuls-designate Decimus Junius Silanus and Lucius Licinius Murena.[61] After his second defeat, Catiline seems to have run out of money and must have been abandoned by his former supporters such as Crassus and Caesar.[62]

Conspiracy

[edit]On 18 or 19 October, Crassus and two other senators visited Cicero's house on the Oppian Hill (near the ruins of the Colosseum) and delivered to the consuls anonymous letters, warning that Catiline was planning a massacre of leading politicians, and advising them to leave the city. Cicero convened the senate and had them read aloud.[58] A few days later, on 21 or 22 October, an ex-praetor reported news that an ex-Sullan centurion – Gaius Manlius – who had supported Catiline's bid for the consulship had raised an army in Etruria.[63] The senate acted immediately, usually dated to the 21st, to pass a senatus consultum ultimum directing the consuls to take whatever actions they believed necessary for state security. When news of the decree arrived to Manlius he declared an open rebellion.[63]

Some modern scholars reject a connection between Manlius and Catiline at this early point, arguing that Manlius' rebellion may have been separate from Catiline's alleged conspiracy and that the conspiracy only came into actual fruition when Catiline joined Manlius' rebellion when leaving Rome for exile and seeing nothing to lose. There are, however, no indications of this in the ancient sources.[64]

Catiline's indebtedness – if he was in fact indebted, there is little evidence one way or the other[65] – was not the sole cause of his conspiring: "wounded pride and fierce ambition" played a great role in his decision-making.[66] Many of the senatorial members of the conspiracy were men who had been ejected from the senate for immorality, corruption, or seen their careers stall out (especially in attempts to reach the consulship).[67] The men who joined Manlius' rebellion were largely two groups: poor farmers who had been dispossessed by Sulla's confiscations after the civil war and ruined Sullan veterans seeking more riches.[68] Cicero, in his invectives, naturally focused on the ruined Sullan veterans, who were unpopular; but at the end, Catiline likely kept only the support of the dispossessed Etruscans who had "nowhere else to go".[69] Altogether, these men had mixed backgrounds and no "single-minded purpose [can] readily be ascribed" to them.[70]

Flight from the city

[edit]

While the consuls fortified central Italy, reports also filtered in of slave revolts in the south. Two generals[b] who were waiting for their triumphs to be approved were then dispatched with men to garrison the northern approaches to Rome and southern Italy.[71] Catiline for his part remained in Rome since the letters sent to Crassus were anonymous and thus insufficient to prove Catiline's involvement.[71]

On 6 November, Catiline held a secret meeting in Rome at the house of Marcus Porcius Laeca where he planned to go to Manlius' army, for other members of the conspiracy to take charge of the nascent revolts elsewhere in Italy, for conspirators in Rome to set fires in the city, and for two specific conspirators to assassinate Cicero the next morning.[72] Cicero exaggerates Catiline's supposed intention to raze the city as a means to turn the urban population against him – a story further embellished in Plutarch[73] – it is more likely that Catiline's fires were intended only to create exploitable confusion for his army.[72]

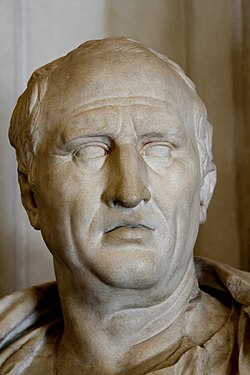

The next day, on 7 November, the assassins found Cicero's house shut against them and Cicero convened the senate later that day at the Temple of Jupiter Stator reporting the threat to his life and then delivering the First Catilinarian denouncing Catiline. Catiline, who was already planning to leave the city, offered to go into exile if the senate would so decree. After Cicero refused to bring up such a motion, Catiline protested his innocence and insulted Cicero's ancestry, calling him a "squatter".[74] He thereafter left the city, claiming that he was going into voluntary exile at Massilia "to spare his country a civil war".[75] On his departure, he sent a letter to his old friend and ally Quintus Lutatius Catulus Capitolinus, which Sallust copied into Bellum Catilinae.[76] In the letter, Catiline defends himself as an injured party who took up the cause of the less fortunate in accordance with his patrician forebears' custom; he vehemently denies that he goes into exile due to his debts and commits his wife Orestilla to Catulus' care.[77]

He left the city on the road to Massilia, but in Etruria, he went to a weapons cache before diverting for Faesulae where he met up with Manlius' forces. Upon his arrival, he proclaimed himself consul and adopted consular regalia. When news of this reached Rome, the senate declared Catiline and Manlius hostes (public enemies) and dispatched Antonius at the head of an army to subdue him.[78]

Death

[edit]

In late November, Antonius' forces approached from the south. He decamped from Faesulae and moved near the mountains but remained close enough to the town to be in striking distance. When Antonius' forces arrived in the vicinity of the town, he avoided battle.[80]

Catiline's coconspirators in Rome had been caught out by Cicero with the aid of some Gallic envoys.[81] After a fierce senate debate, they were executed without trial on 5 December.[82] When news of their death arrived to Catiline's camp, much of his army melted away, leaving him with perhaps a bit more than three thousand men. Hoping to escape into Gaul, his escape from Italy was blocked when Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer – proconsul in Cisalpine Gaul[83] – garrisoned the Apennine passes near Bononia.[84]

Antonius kept his men relatively docile near Faesulae, but after he received reinforcements from then-quaestor Publius Sestius in the last days of December, he moved out. Catiline, for his part, seeing his escape blocked, turned south to face Antonius, perhaps believing that Antonius would not fight as hard. They met at Pistoria, modern day Pistoia. Descending from the heights, he offered battle to Antonius' army, possibly on 3 January 62 BC.[85]

On the day of the battle, Antonius gave operational command to Marcus Petreius (Sallust claims he was stricken with gout[86]), an experienced lieutenant,[87] who broke through the Catilinarian centre with the praetorian cohort, forcing Catiline's men to flight.[88] Catiline and his diehard supporters fought bravely and were annihilated:[89] "they were desperate men who did not wish to survive their defeat".[87]

Sallust's account reads:

When the battle was ended it became evident what boldness and resolution had pervaded Catiline's army. For almost every man covered with his body, when life was gone, the position which he had taken when alive at the beginning of the conflict. A few, indeed, in the centre, whom the praetorian cohort had scattered, lay a little apart from the rest, but the wounds even of these were in front. But Catiline was found far in advance of his men amid a heap of slain foemen, still breathing slightly, and showing in his face the indomitable spirit which had animated him when alive.[90]

Legacy

[edit]In Roman literature, Catiline's figure became often used as a byword for "villainy".[91] Politicians quickly distanced themselves from his failed revolt; others tried to discredit rivals by linking them to Catiline's conspiracy after the fact.[92] Cicero, who claimed for himself the credit of saving the state from Catiline's revolt, later praised Catiline's personal qualities in a defence speech for someone accused of being a co-conspirator: Cicero paints Catiline as a good motivator, effective general, sociable, and strong as reasons for why so many men were willing to associate with him (for Cicero's client, however, only as a non-conspiring friend).[93][94] The history of Sallust, written around the time of the Second Triumvirate, painted Catiline as a thoroughgoing disrepute who had from an early time wanted to destroy his own country and symbolised the moral decline that Sallust identified as the cause of the republic's collapse:

S. [Sallust] prefers to present Catiline as a through-going villain, the product of the corrupt age, who was bent on the destruction of the state from the very beginning...[95]

Livy used the Catilinarian conspiracy as a template to fill in shaky portions of early Roman history. For example, the conspiracy of one Marcus Manlius, who rose up against the elite with the support of poor plebs, both gives a speech patterned on Cicero's First Catilinarian and takes actions patterned on the real Catiline's.[96] Virgil, in the Aeneid (written during the reign of Augustus), depicts Catiline as being tortured in the underworld by the Furies.[96][97]

Into the imperial period, Catiline's name was used as a derogatory nickname of unpopular ruling emperors.[91] However, his reputation as an advocate for the dispossessed rural plebs seemed to carry to some degree in rural parts of northern Italy at least until the mediaeval period. In Tuscany, a mediaeval tradition had Catiline survive the battle and live out his life as a local hero; another version gives him a son, Uberto, who eventually spawns the Uberti dynasty in Florence.[98]

While history has often viewed Catiline through the lenses of his enemies – especially in the vein of Cicero's four Catilinarians – some modern historians have reassessed Catiline. The first major attempt was Edward Spencer Beesly in 1878, who argued against the then-prevailing view that Catiline was "a demon breathing murder, rapine, and conflagration, with bloodshot eyes and pallid face, luring on weak and depraved young men to the damnation prepared for himself".[99] Beesly's defences have been followed more recently by others, such as Waters 1970 and Seager 1973. Waters' admittedly "largely hypothetical"[100] narrative depicts the Catilinarian conspiracy largely as a Ciceronean fiction framing Catiline and the "co-conspirators" for Cicero's own political advancement.[101] Seager's defence does not go so far, but instead argues the conspiracy was purposefully incited by Cicero and the senate to purge Italy of men who might join with Pompey if he were to follow in Sulla's footsteps on his then-imminent return from the Third Mithridatic War.

Other classicists have argued that Catiline was a precursor of Caesar or that he rebelled to oppose senatorial corruption and incompetence.[c] But, largely, such defences are highly speculative, as the literary evidence that survives is overwhelmingly Ciceronean and biased against Catiline.[102]

Cultural depictions

[edit]

- At least two major dramatists have written tragedies about Catiline: Ben Jonson, the English Jacobean playwright, wrote Catiline His Conspiracy in 1611, depicting Catiline as "a sadistic anti-hero";[103] Catiline was the first play by the Norwegian "father of modern drama" Henrik Ibsen, written in the aftermath of the 1848 revolutions and depicting Catiline as hero struggling against his world's corruption.[98]

- Antonio Salieri wrote an opera tragicomica in two acts on the subject of the Catilinarian conspiracy entitled Catilina to a libretto by Giambattista Casti in 1792. The work was left unperformed until 1994 due to its political implications during the French Revolution. Here, serious drama and politics were blended with high and low comedy: the plot centered on a love affair between Catiline and a daughter of Cicero as well as the historic political situation.

- Steven Saylor's 1993 novel Catilina's Riddle revolves around the intrigue between Catiline and Cicero in 63 BC. Catiline also plays a major character in Steven Saylor's short story "The House of the Vestals".

- Catiline's conspiracy and Cicero's consular actions figure prominently in the novel Caesar's Women by Colleen McCullough as a part of her Masters of Rome series.

- SPQR II: The Catiline Conspiracy, by John Maddox Roberts, discusses Catiline's conspiracy.

- Robert Harris' 2006 book Imperium, based on Cicero's letters, covers the developing career of Cicero with many references to his increasing interactions with Catiline. The sequel, Lustrum (issued in the United States as Conspirata), deals with the five years surrounding the Catilinarian conspiracy.

- The Roman Traitor or the Days of Cicero, Cato and Catiline: A True Tale of the Republic by Henry William Herbert originally published in 1853 in two volumes.

- A Pillar of Iron by Taylor Caldwell, published in 1965, tells of the life of Cicero, especially in relation to Catiline and his conspiracy.

- A Slave Of Catiline is a book by Paul Anderson that tells of a slave who helps and then hinders Catiline's conspiracy.

- A novel on the conspiracy, The Fall of the Republic, written by Scott Savitz, was published in September 2020.

- Bertolt Brecht's unfinished novel The Business Affairs of Mr Julius Caesar provides a fictionalised account of the Catilinarian conspiracy in which Caesar and Crassus are alleged to be involved for financial gain.

- Adam Driver portrays Cesar Catilina, a character from Francis Ford Coppola's 2024 sci-fi epic film Megalopolis, which is a fictionalised interpretation of the Catiline Conspiracy set in an imagined modern futuristic America. Driver stars opposite Giancarlo Esposito, who portrays a character named Mayor Franklyn Cicero. In the film, Driver's character is pitted against Esposito's character in a rivalry and battle for political control of New Rome. The film also centers around Cesar Catilina's love affair with Mayor Cicero's daughter, Julia Cicero played by Nathalie Emmanuel.[104]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The first consular comitia of 66 BC returned Publius Autronius Paetus and Publius Cornelius Sulla. The second comitia, from which Catiline was excluded, returned Lucius Manlius Torquatus and Lucius Aurelius Cotta.[31]

- ^ The two generals were Quintus Marcius Rex and Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus; they had served as consul in 68 and 69 BC, respectively.[71]

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 3 n. 4, citing:

- Kaplan, Arthur (1968). Catiline: the man and his role in the Roman revolution. Exposition Press. ("Catiline as a precursor of Caesar")

- Fini, Massimo (1996). Catilina: ritratto di un uomo in rivolta (in Italian). Milan. ISBN 8-8044-0494-9. OCLC 36751571.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ("Catiline as the opponent of senatorial corruption") - Galassi, Francis (2014). Catiline, the monster of Rome. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5941-6583-2. ("too full of errors to make an effective case"; very negatively reviewed at Fletcher, KFB (2015-01-30). "Review of: Catiline, the monster of Rome". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. ISSN 1055-7660.)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Krebs 2008.

- ^ a b Berry 2020, p. 10.

- ^ Sall. Cat., 5.1.

- ^ Badian 2012a.

- ^ See Digital Prosopography of the Roman Republic s.v. "Sergius".

- ^ Zmeskal 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Münzer, Friedrich (1927). "Sergius 39". Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (in German). Vol. II A, 2. Stuttgart: Butcher. col. 1719.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Badian 2012b.

- ^ Taylor 1960, p. 253, citing ILS 8888.

- ^ Taylor 1960, p. 253.

- ^ Marshall 1985, p. 127.

- ^ Badian 2012b; Broughton 1952, p. 72.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 72.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 72; Zmeskal 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Marshall 1985, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Marshall 1985, pp. 132–33; Berry 2020, pp. 12–13 ("There are good reasons for thinking that Catiline was not the man responsible for the execution and that Gratidianus was actually killed by Catiline's friend ... Catulus").

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 13.

- ^ Alexander 1990, p. 83.

- ^ Alexander 1990, p. 83; Berry 2020, p. 14; Broughton 1952, p. 114.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 14, citing Asc. 91C, commenting "Cicero alluded to the trial in In toga candida in a way that ingeniously implied both Fabia's innocence and Catiline's guilt".

- ^ Broughton 1952, pp. 138, 141 (footnote noting that it must have been in or before 68 BC)..

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 617. Entry in index of offices: "Leg., Lieut. 82, Pr. 68, Propr. Africa 67–66."

- ^ Berry 2020.

- ^ Evans, Richard J (1987). "Catiline's wife". Acta Classica. 30: 69–72. ISSN 0065-1141. JSTOR 24591812.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 18, citing Sall. Cat., 15.2.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 147.

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 340.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 147, citing Sall. Cat., 18.3 and Cic. Cael. 10.

- ^ Seager 1964, p. 338; Broughton 1952, p. 157.

- ^ Seager 1964, pp. 338–39.

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 342.

- ^ Wilson, Mark (2021). Dictator: the evolution of the Roman dictatorship. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 303 n. 1. ISBN 978-0-472-12920-1. OCLC 1243162549.

- ^ Phillips 1976, p. 441. "It is clear that so-called First Catilinarian conspiracy... is fictitious".

- ^ Waters 1970, "I shall not discuss the once believed-in "First Catilinarian conspiracy", a phantom now, it is to be hoped, exorcised for ever".

- ^ Seager 1964, p. 338 n. 1. "It is now widely held that the conspiracy is wholly fictitious".

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 342.

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 345.

- ^ Alexander 1990, pp. 106–07, n. 3, "Cicero's statement (Att. 1.2.1) ... has been taken to suggest that the prosecutor was working with the defence to secure an acquittal. Gruen (Athenaeum 1971) 59–62, however, argues that Clodius [the prosecutor] did not commit praevaricatio".

- ^ Cic. Att. 1.2.

- ^ Alexander 1990, pp. 106–07.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1992, p. 348.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Berry 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Alexander 1990, pp. 108–09.

- ^ Gruen 1995, pp. 76–77 n. 124.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 426; Beard 2015, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 351.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 425.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1992, p. 352.

- ^ Wiseman 1992, p. 353.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 21.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 25.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 26.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 29.

- ^ a b Berry 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 30.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 429 n. 110.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 172.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 26, 30.

- ^ a b Berry 2020, p. 32.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 32; Seager 1973, pp. 240–41; Waters 1970, p. 201.

- ^ Waters 1970, p. 213 n. 43.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 420.

- ^ Gruen 1995, pp. 417–19.

- ^ Gruen 1995, pp. 424–25.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 28.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 422.

- ^ a b c Berry 2020, p. 33.

- ^ a b Berry 2020, p. 34.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 34, citing Plut. Cic. 18.2, which reports a "not credible" scheme involving a hundred men to raze the whole city.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 36, citing Sall. Cat., 31.7–8.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 37.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 38, citing Sall. Cat., 35.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 42.

- ^ Crawford 1974, pp. 441–42; Berry 2020, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Sumner 1963, p. 215.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 42–46.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 176.

- ^ Sumner 1963, pp. 215–16.

- ^ Sumner 1963, p. 217.

- ^ Sall. Cat., 59.4.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1992, p. 360.

- ^ Sall. Cat., 60.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 52.

- ^ Sall. Cat., 61.

- ^ a b Beard 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Gruen, Erich S. (1969). "Notes on the "first Catilinarian conspiracy"". Classical Philology. 64 (1): 21. doi:10.1086/365439. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 268006. S2CID 162267188.

- ^ Berry 2020, pp. 5–7.

- ^ See generally Cic. Cael.

- ^ Ramsey 2007, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Beard 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Aen. 8.666–70.

- ^ a b Beard 2015, p. 49.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Waters 1970, p. 215.

- ^ Waters 1970, pp. 213, 215.

- ^ Berry 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Beard 2015, p. 50.

- ^ "MEGALOPOLIS". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

Modern sources

[edit]- Alexander, Michael (1990). Trials in the late Roman republic, 149 BC to 50 BC. Phoenix. Vol. 26. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5787-X.

- Beard, Mary (2015). SPQR: a history of ancient Rome (1st ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87140-423-7. OCLC 902661394.

- Berry, DH (2020). Cicero's Catilinarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-751081-0. LCCN 2019048911. OCLC 1126348418.

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Crawford, Michael (1974). Roman republican coinage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07492-6. OCLC 450398085.

- Gruen, Erich (1995). The last generation of the Roman republic. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02238-6.

- Hornblower, Simon; et al., eds. (2012). Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Badian, Ernst (2012a). "nobilitas". In OCD4 (2012).

- Badian, Ernst (2012b). "Sergius Catilina, Lucius". In OCD4 (2012).

- Krebs, Christopher B (2008). "Catiline's ravaged mind: "vastus animus" (Sall. BC 5.5)". Classical Quarterly. 58 (2): 682–686. doi:10.1017/S0009838808000773.

- Marshall, Bruce (1985). "Catilina and the execution of M Marius Gratidianus". Classical Quarterly. 35 (1): 124–133. doi:10.1017/S0009838800014610. ISSN 1471-6844. S2CID 170502218.

- Phillips, EJ (1976). "Catiline's Conspiracy". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 25 (4): 441–448. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435521.

- Ramsey, JT (2007). "Commentary". Sallust's Bellum Catilinae. By Sallust (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-3337-7. OCLC 560589383.

- Seager, Robin (1964). "The first Catilinarian conspiracy". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 13 (3): 338–347. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4434844.

- Seager, Robin (1973). "Iusta Catilinae". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 22 (2): 240–248. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435332.

- Sumner, GV (1963). "The last journey of L Sergius Catilina". Classical Philology. 58 (4): 215–219. doi:10.1086/364820. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 266531. S2CID 162033864.

- Taylor, Lily Ross; Linderski, Jerzy (2013) [First published 1960]. Voting districts of the Roman republic. Papers and monographs of the American Academy in Rome. Vol. 34 (Updated ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-4721-1869-4.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1960). Voting districts of the Roman republic: the thirty-five urban and rural tribes (1st ed.). American Academy in Rome.

- Waters, KH (1970). "Cicero, Sallust and Catiline". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 19 (2): 195–215. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435130.

- Wiseman, T. P. (1992). "The senate and the populares, 69–60 BC". In Crook, J. A.; et al. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 327–67. ISBN 0-521-25603-8.

- Zmeskal, Klaus (2009). "Sergii". Adfinitas: die Verwandtschaften der senatorischen Führungsschicht der römischen Republik von 218-31 v. Chr (in German). Vol. 2. Passau: K. Stutz. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-88-849304-1.

Ancient sources

[edit]- Sallust (1921) [1st century BC]. "Bellum Catilinae". Sallust. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Rolfe, John C. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Cicero (1856). "Against Catiline". Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero. Vol. 2. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke. London: Henry G. Bohn – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Cicero (1937). In Catilinam 1-4. Pro Murena. Pro Sulla. Pro Flacco. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Lord, Louis E. Harvard University Press.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Catiline at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Catiline at Wikimedia Commons