Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

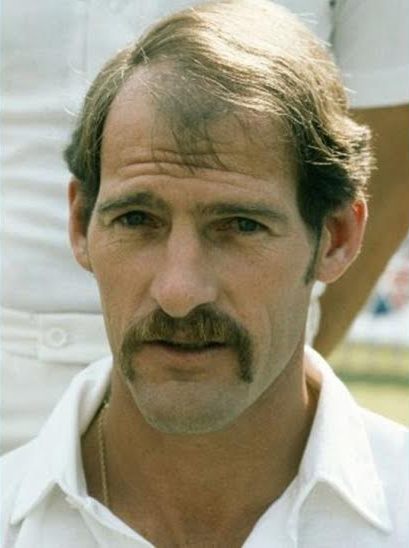

Clive Rice

View on Wikipedia

Clive Edward Butler Rice (23 July 1949 – 28 July 2015) was a South African international cricketer.[1] An all-rounder, Rice ended his First Class cricket career with a batting average of 40.95 and a bowling average of 22.49. He captained Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club from 1979 to 1987.

Key Information

His career coincided directly with South Africa's sporting isolation, and his international experience was limited to his post-prime days. He played three One Day Internationals for South Africa following the country's return from sporting isolation. He was controversially left out of the squads for the one-off Test against West Indies and the 1992 Cricket World Cup. Despite this he is widely regarded as one of the best all-rounders of his generation, alongside Imran Khan, Ian Botham, Kapil Dev and his county team-mate Richard Hadlee.[2][3][4][5]

On 28 July 2015, Rice died in hospital at the age of 66, suffering from a brain tumour.[6]

Early and personal life

[edit]Rice was born to Patrick and Angela[7] on 23 July 1949 in Johannesburg, Transvaal Province, Union of South Africa. Rice's grandfather Philip Salkeld Syndercombe Bower played cricket for Oxford University while his brother Richard was selected for Transvaal but was unable to play due to exams.[7]

Rice worked for a street-lighting company called Envirolight in Johannesburg and his wife Susan heads a Sports Tour and Bush safari company. The couple have two children.

Career

[edit]Domestic career

[edit]Rice began his career with Transvaal in 1969 and was called up for South Africa's (ultimately cancelled) tour of Australia in 1971–72.[8] In South African domestic cricket he successfully led the 1980s Transvaal, known as the "Mean Machine",[9] to three Castle Currie Cups and other one-day competition victories. Toward the end of his playing career, he played for and captained Natal.

He became the first cricketer to score 5000 runs and to take 500 wickets in List A cricket history[10]

Career in English domestic cricket

[edit]Rice played for Nottinghamshire in the English County Championship in a team that also featured internationals Richard Hadlee and Derek Randall. As captain, he led the team to the County Championship title in both 1981 and 1987, winning the prestigious award of being named a Wisden cricketer of the year for his exploits in 1981.[11] He later played for Scotland.

International cricket

[edit]Along with other South African players, Rice was excluded from international cricket by the sporting boycott of South Africa due to his country's policy of apartheid.

Rice joined World Series Cricket setup in 1978-79. He played three Supertests for the WSC World XI, enjoying three victories. In the first one, against Australian XI, the World XI were 5-53 when Rice came to the wicket, and scored 41, taking the World XI to 6-138 - these runs proved crucial in the team's victory. Against the West Indies XI, Rice made 83 and took three wickets as WSC World XI won by an innings and 44 runs. In his third Supertest, against Australia, Rice took three tickets.

During the 1980s, a number of rebel cricket teams visited South Africa to play unofficial "Test" matches. Rice captained the home team for the majority of these fixtures.

In 1985-86 an Australian XI toured. The South Africa XI won the 3-match test series 1-0, and the 6-match one-day series 4-2. In the third test, Rice took a hattrick in Australia's second innings. In the 2nd one-day match, Rice scored 91 off 93 balls; in the third he made 78 and took 3-25; in the fourth he scored 44 and took 4-45; in the 6th he made 95.

Rice was able to make his debut in official international cricket in 1991, when, aged 42, he played in—and captained—South Africa's first One Day International, in a match against India at Eden Gardens, Calcutta.[12] Rice finished with averages of 13 with the bat and 57 with the ball from his three One Day International matches.[13]

Alongside Jimmy Cook, he was controversially dropped for the 1992 Cricket World Cup squad. He was widely regarded as the most credible candidate for team captain due to his decades of experience.[14] Rice initially refused to comment on his omission, but was reported to have been visibly upset when the team was announced.[15] The Johannesburg Sunday Times conducted a poll which showed that 47 out of South Africa's top 66 cricketers opposed the exclusion of Rice and other senior players. Some were quoted in the paper as saying the selectors were "clowns" and they should resign for the omission of three "automatic choices". Peter van der Merwe, the chairman of the selection panel, dismissed the poll and said it did not concern him.[16] After being left out of the world cup squad, which he attributed to personal differences with van der Merwe, Rice stood down as Transvaal captain for the remainder of the domestic season in order to be a commentator for the world cup on the Nine Network in Australia.[17]

In 1993 he captained the South African team at that years Hong Kong Sixes tournament.[18]

Later career

[edit]In 1995, after just one season since retiring from first-class cricket, Rice was appointed to South Africa's national selection panel on the nomination of the Transvaal Cricket Board.[19] He worked as coach for Nottinghamshire and encouraged Kevin Pietersen to leave South Africa to qualify for England.[20][21][22]

Opinions about match fixing

[edit]In September 2010, Rice claimed in an interview to Fox News that betting syndicates were involved in the deaths of Pakistan coach Bob Woolmer and former South African captain Hansie Cronje. Fox Sports quoted Rice as saying: "These mafia betting syndicates do not stop at anything and they do not care who gets in their way." Former Pakistan coach Geoff Lawson had earlier told Fox Sports that match-fixing "might not be about money, it might be about extortion, and all the things that go on".[23]

Illness and death

[edit]Rice was diagnosed with a brain tumour in September 1998 and received treatment in Hanover, Germany.[24] In February 2015, Rice collapsed at his house in Johannesburg and scans at a local hospital found that, as his tumour was located deep down, it could not be removed by a neurosurgeon by invasive surgery.[25] Rice then went to Health Care Global in Bangalore, India and received robotic radiation treatment to have the tumour removed. The surgery was successful and Rice returned home in March 2015.[26] On the morning of 28 July 2015, Rice died from sepsis in the Morningside hospital in Johannesburg.

References

[edit]- ^ Mason, Peter (28 July 2015). "Clive Rice obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Vijaya Kumar, K.C. (8 March 2015). "Can't doesn't exist, the word 'can' does: Clive Rice". thehindu.com. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Titans hail Rice's contribution to the game". Sport24. 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Culley, Jon (28 July 2015). "Clive Rice: Inspirational cricketer who was denied an international career by apartheid but led Nottinghamshire to glory". independent.co.uk. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Berry, Scyld (28 July 2015). "Clive Rice: Best cricketer who never played a Test". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Clive Rice dies aged 66". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ a b Sproat, p. 341.

- ^ "Rice to captain SA team". The Press. 5 November 1991. p. 34.

- ^ Player Profile, Cricinfo, Retrieved on 29 March 2009

- ^ "Records | List A matches | All-round records | 5000 runs and 500 wickets | ESPN Cricinfo". Cricinfo. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Wisden's Five Cricketers of the Year, Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, Retrieved on 29 March 2009

- ^ India v South Africa, South Africa in India 1991/92 (1st ODI), ODI no. 686, Cricinfo, Retrieved on 16 April 2009

- ^ Player Profile, Cricinfo, Retrieved on 16 April 2009

- ^ "Selectors toss Rice, Cook out of squad". The Press. 31 December 1991. p. 30.

- ^ "Team selection slated". The Press. 2 January 1992. p. 26.

- ^ "South African cricket row". The Press. 15 January 1992. p. 30.

- ^ "Rice quits captaincy to comment on cup". The Press. 3 February 1992. p. 31.

- ^ "NZ for sixes". The Press. 20 July 1993. p. 40.

- ^ "Rice appointed SA national selector". The Press. 28 June 1995. p. 68.

- ^ South Africa's decline because of 'apartheid in reverse', Cricinfo, Retrieved on 29 March 2009

- ^ Rice furious at 'apartheid in reverse', The Telegraph, Retrieved on 24 July 2011

- ^ Richard Williams (8 January 2009). "Just not cricket ... the most un-English of England captains heads for the pavilion". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Cronje, Woolmer murdered by mafia betting syndicates: Rice – Thaindian News". Thaindian.com. 8 September 2010. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Clive Rice diagnosed as having a brain tumour (28 September 1998)". ESPNcricinfo. 27 September 1998. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Clive Rice confident laser knife can remove new tumours". news24.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Clive Rice successfully returns home to SA from India after getting brain tumour treated in HCG". Business Standard. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Sproat, I. (1988) The Cricketers' Who's Who 1988, Willow Books: London. ISBN 0 00 218285 8.

External links

[edit]Clive Rice

View on GrokipediaEarly life

Family background and education

Clive Rice was born on 23 July 1949 in Johannesburg, Transvaal Province, Union of South Africa, to Patrick Rice and Angela Rice (née Bower).[4] His maternal grandfather, Philip Bower, had played first-class cricket for Oxford University in 1919, fostering an early family connection to the sport that influenced Rice's development.[4] [5] The Rice family maintained strong English roots through both parental lines, reflecting a heritage tied to British sporting traditions.[2] Rice received his secondary education at St John's College in Johannesburg, a prominent independent school known for its cricket program, where he represented the school XI in 1965 and 1966 despite being notably small in stature during his final year.[6] [4] He later pursued higher education at the University of Natal, earning a Bachelor of Commerce degree while balancing emerging cricketing commitments.[4] [7] This academic foundation supported his entry into professional cricket, as he debuted in first-class matches for Transvaal shortly after turning 20 in the 1969–70 season.[7]Domestic career

Transvaal cricket

Clive Rice made his first-class debut for Transvaal during the 1969–70 Currie Cup season, shortly before South Africa's international isolation due to apartheid policies.[1] Over the course of his domestic career, he established himself as a formidable all-rounder for the province, amassing 7,632 runs and claiming 364 wickets in first-class matches, figures that made him the only Transvaal (later Gauteng) player to surpass 5,000 runs and 300 wickets for the team.[8] As captain, Rice transformed Transvaal into a dominant force, earning the nickname "Mean Machine" for their aggressive and resilient style in the 1970s and 1980s.[1] Under his leadership, the team secured multiple Currie Cup titles, including victories in the 1979–80 and 1980–81 seasons, when they also claimed the Datsun Shield one-day competition; in the latter campaign, Rice topped the national first-class bowling averages with 43 wickets.[9] Transvaal won the Currie Cup a total of ten times over the twenty years Rice represented them, reflecting the sustained success during his tenure.[6] Rice's individual contributions were equally impressive, highlighted by his 1978–79 season aggregate of 1,871 runs at an average of 66.82, and in 1980, when he scored five centuries, including two unbeaten innings in a single match against Western Province.[9] His all-round prowess and tactical acumen were instrumental in elevating Transvaal's status in South African domestic cricket amid the era's sporting isolation.[4]English county cricket with Nottinghamshire

Rice joined Nottinghamshire in 1975 as the overseas player succeeding Garry Sobers.[6] He quickly established himself as a leading all-rounder, topping both the batting and bowling averages in the County Championship in 1976 and 1977, as well as in the Sunday League in 1977.[6] In 1976, he scored his highest first-class innings for the county, 246 against Sussex, featuring six sixes and 32 fours in just over five hours.[6] He received his Nottinghamshire cap in 1975 and earned the Cricket Society's Wetherall Award for the leading all-rounder in English first-class cricket in 1977, 1979, and 1981.[10] Appointed captain in July 1978, Rice led Nottinghamshire until his retirement at the end of the 1987 season.[6] Under his leadership, the county secured the County Championship title in 1981—their first in over 50 years—and repeated the feat in 1987, also achieving the "Double" by winning the one-day knockout competition that year.[6] In the 1981 Championship-winning season, Rice averaged 56 with the bat and claimed 65 wickets.[11] Over his Notts career, Rice amassed 17,053 first-class runs at an average of 44.29, including his top score of 246, and took 476 wickets at 23.58, alongside 268 catches.[6] In limited-overs Sunday League matches, he scored 6,265 runs at 42.33 and captured 184 wickets at 22.90.[6] His contributions earned him recognition as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1981.[6]Apartheid-era isolation and unofficial play

Impact on international opportunities

The international sporting boycott against South Africa, imposed by the International Cricket Conference in 1970 in response to the apartheid regime's racial policies, effectively barred Clive Rice from official Test cricket during the prime years of his career.[4] Rice, who made his first-class debut for Natal in January 1969 at age 19, was rapidly establishing himself as a promising all-rounder by the time the ban took hold; South Africa's last Test series before isolation had concluded in 1970, leaving Rice without opportunities against full member nations until 1992.[5] This 22-year exclusion spanned his physical peak, from his early 20s through his mid-30s, denying him an estimated 15-20 potential Test appearances based on his domestic dominance, where he amassed over 25,000 first-class runs and 370 wickets.[12] Rice was specifically selected for South Africa's planned 1971-72 tour of Australia, which was cancelled amid the boycott, marking an early lost chance to compete at the highest level.[4] Subsequent invitations to unofficial series, such as against a World XI in 1975 or rebel tours organized by figures like Kerry Packer and Ali Bacher in the 1980s, provided partial exposure but lacked official status and carried reputational risks, including bans from bodies like the England and Wales Cricket Board.[5] These alternatives, while allowing Rice to face international stars like Viv Richards and Malcolm Marshall, could not replicate the prestige or selection implications of ICC-sanctioned matches, further stunting his global recognition despite his reputation as a world-class all-rounder capable of 50-plus Test averages in batting and sub-25 in bowling.[13] Upon South Africa's readmission to international cricket in 1992, Rice, then aged 42, captained the team in three One Day Internationals during the World Cup but played no Tests, as his advancing age and the emergence of younger players like Hansie Cronje limited his role.[14] This late entry underscored the boycott's irreversible impact, as Rice retired from first-class cricket in 1994 without a single official Test cap, a outcome contemporaries attributed to apartheid-era isolation rather than personal shortcomings.[5] The era's restrictions not only curtailed statistical legacies but also deprived Rice of leadership experience in multilateral formats, confining his influence to domestic and county circuits.[12]Participation in rebel and invitation tours

During South Africa's exclusion from official international cricket due to the international sports boycott against apartheid, Clive Rice participated in a series of unofficial Test matches against rebel touring teams from overseas, primarily in the 1980s. These encounters provided limited opportunities for competitive international-level play, with Rice often leading the South African side as captain. He featured prominently in the 1983–84 series against a West Indian XI, contributing with both bat and ball, though specific match statistics from these fixtures are inconsistently recorded due to their unofficial status.[4] Rice assumed the captaincy for key matches in subsequent rebel series, including the 1985–86 tour by an Australian XI led by Kim Hughes, where South Africa secured victories in the majority of the six "Tests" scheduled. His leadership emphasized aggressive play, leveraging his all-round abilities to stabilize innings and direct the bowling attack against seasoned international opponents. In the 1986–87 Australian rebel follow-up and the 1989–90 English rebel tour under Mike Gatting, Rice again captained selectively, taking over for critical games such as the third and fourth "Tests" against England after a change in leadership following an ODI series loss; these matches highlighted his tactical acumen in high-stakes, unsanctioned contests.[4][15] Earlier in the isolation period, Rice took part in invitation tours organized by English promoter Derrick Robins, which brought non-sanctioned overseas XIs to South Africa between 1971 and 1981. These private arrangements, distinct from the later fully rebel tours, allowed Rice to face international-caliber players in matches billed as Tests, honing his skills amid the boycott; for instance, he played in the 1981–82 series against an England XI, scoring and bowling effectively in drawn encounters. Such fixtures, while not carrying official weight, maintained competitive standards for South African players like Rice, who averaged over 40 with the bat in first-class cricket during this era.[2]Official international career

1992 Test debut and captaincy

Clive Rice did not make a Test debut in 1992 or at any point in his career, despite his status as one of South Africa's premier all-rounders during the apartheid-era isolation. South Africa's readmission to international cricket began with One Day Internationals (ODIs) against India in November 1991, where Rice, aged 42, captained the team in all three matches, claiming 4 wickets at an average of 15.75. His official international appearances were confined to these ODIs, as selectors favored Kepler Wessels for Test captaincy and younger players for the longer format upon formal re-entry.[17] The Proteas' first official Test post-isolation occurred on 13 November 1991 against India at Kingsmead, Durban, resulting in a 9-wicket victory under Wessels' leadership; Rice was not selected. Subsequent 1992 Tests against New Zealand (two matches, both wins) and Pakistan (a loss) similarly excluded him, reflecting concerns over his age—43 by mid-1992—and a perceived decline from his peak domestic form, though his first-class record stood at over 25,000 runs and 426 wickets.[1] Rice's exclusion was controversial among supporters, given his experience in unofficial "rebel" Tests during isolation, but Wessels' tactical acumen and batting reliability secured the role.[9] Rice's leadership extended to mentoring roles in 1992, including managing a South African cricket academy, but he retired from first-class cricket after the 1991/92 domestic season, ending any prospect of Test involvement. His unfulfilled Test ambition underscored the timing of South Africa's 22-year ban (1970–1991), which robbed him of opportunities during his prime from the mid-1970s to late 1980s.[1][17]Leadership and playing style

Captaincy achievements

Rice captained Transvaal from the mid-1970s, leading the side—nicknamed the "Mean Machine" for its aggressive and dominant play—to three Currie Cup titles in the 1980s, alongside multiple one-day domestic trophies.[18] Under his guidance, Transvaal secured victories in the 1980–81, 1981–82, and 1984–85 seasons, establishing the team as a powerhouse in South African first-class cricket during the isolation era.[4] His tactical acumen and motivational leadership fostered a winning culture, with Transvaal claiming the Currie Cup ten times across the two decades Rice represented the province.[6] In English county cricket, Rice took over Nottinghamshire's captaincy in 1978, transforming a struggling side into champions. He guided them to the County Championship title in 1981—their first in 52 years—where he contributed 65 wickets at an average of 20.78 and scored 1,095 runs at 56.00.[11] Nottinghamshire repeated the feat in 1987, achieving a championship and one-day double, with Rice's all-round performances underpinning eight of the team's 11 Championship wins that season occurring at Trent Bridge.[6] His captaincy earned him recognition as one of Wisden's Cricketers of the Year in 1981.[1] On the international front, Rice captained South Africa in their three official ODIs upon readmission, defeating India 2–1 in the November 1991 series in Kolkata, Ahmedabad, and Gwalior—marking a successful debut in limited-overs internationals after 21 years of exile.[1] At age 42, he became the oldest player to captain South Africa on debut, though he played no Tests and was succeeded by Kepler Wessels for the 1992 World Cup.[1]Batting, bowling, and all-round contributions

Clive Rice was a right-handed batsman and right-arm fast-medium bowler whose all-round abilities underpinned his domestic dominance across two decades. In first-class cricket, he amassed 26,331 runs at an average of 40.95, including 48 centuries, while capturing 930 wickets at 22.49, with 23 five-wicket hauls.[19][20] His batting was characterized by solid technique and capacity for big scores under pressure, often anchoring innings for Transvaal and Nottinghamshire; notable performances included twin unbeaten centuries against Somerset in 1980.[9] With the ball, Rice relied on seam movement and accuracy to extract wickets on varied pitches, peaking with returns like 7/27 against Worcestershire.[6] In List A cricket, Rice's contributions were equally prolific, scoring 13,474 runs at 37.32 with 11 centuries and 79 half-centuries across 479 matches, alongside 517 wickets at 22.63.[19] He became the first player to reach 5,000 runs and 500 wickets in the format, highlighting his versatility in shorter games where he adapted his aggressive batting and probing bowling to limited-overs demands.[19] For Nottinghamshire, he tallied 6,265 runs at 42.33 and 184 wickets at 22.90 in the Sunday League alone, blending strokeplay with wicket-taking bursts.[6] Rice's all-round prowess earned him the Wetherall Award for leading all-rounder in English first-class cricket in 1977, 1979, and 1981, reflecting balanced outputs that often swung matches.[21] His dual threat stabilized teams, as seen in Nottinghamshire's 1987 County Championship and NatWest Trophy double, where his 17,053 runs and 476 wickets for the county underscored sustained impact.[22] In limited international exposure, captaining South Africa in three 1992 World Cup ODIs, he scored 26 runs at 13.00 and took 2 wickets at 57.00, though apartheid-era isolation curtailed fuller assessment.[23]| Format | Matches | Batting Runs | Batting Avg | Centuries | Wickets | Bowling Avg | Best Bowling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-class | 482 | 26,331 | 40.95 | 48 | 930 | 22.49 | 7/27 |

| List A | 479 | 13,474 | 37.32 | 11 | 517 | 22.63 | Unknown |

| ODIs | 3 | 26 | 13.00 | 0 | 2 | 57.00 | 1/46 |

Post-retirement activities

Coaching roles

After retiring from playing in 1994, Rice served as director of South Africa's National Plascon Cricket Academy, a role focused on developing young talent through structured training programs. In this capacity, he oversaw coaching initiatives aimed at preparing emerging players for provincial and international levels, drawing on his experience as a former all-rounder and captain.[24] He also managed a South African academy side as early as 1992, blending administrative duties with on-field guidance during the post-isolation reintegration of South African cricket.[25] In 1999, Rice returned to Nottinghamshire as cricket manager and coach, a position he held until 2002, where he emphasized rigorous training regimens to revive the county's performance amid competitive challenges.[26][27] During this tenure, he signed South Africa-born Kevin Pietersen for the club's second XI in 2000, facilitating the batsman's qualification and entry into English domestic cricket, which later propelled Pietersen to international success.[28][29] Rice's approach, informed by his own career in overseas leagues, prioritized technical skill development and mental resilience, though Nottinghamshire's first-team results remained inconsistent under his oversight.[30]Commentary and media involvement

Rice served as a television commentator for Kerry Packer's Channel 9 network, covering South Africa's return to international cricket during the 1992 Cricket World Cup in Australia and New Zealand.[31] This role, which he took up as an alternative to on-field participation after injury prevented his selection for the tournament, lasted approximately one year before he abandoned it, citing a lack of fulfillment in the work.[32] Beyond this stint, Rice maintained a limited media presence, occasionally providing interviews on his career and views on South African cricket governance, such as in discussions published in 2013 and 2015.[33][32] He did not pursue a sustained career in broadcasting, prioritizing instead coaching, academy development, and business ventures.[4]Views on cricket governance

Opinions on match fixing

Clive Rice expressed grave concerns about match fixing in cricket, viewing it as a pervasive threat involving organized crime syndicates that could resort to murder to protect their interests. In a September 2010 interview, he warned that "match-fixing is life threatening," asserting that betting mafias "do not stop at anything" and that players, once involved, "can never escape" due to the syndicate's control.[34] He linked this danger to specific deaths, suspecting that former South African captain Hansie Cronje's 2002 plane crash near George—officially ruled an accident—was orchestrated by those seeking to silence him over his role in the 2000 scandal, describing it as "very fishy."[35][36] Rice extended similar suspicions to Pakistan coach Bob Woolmer's death on March 18, 2007, in Jamaica, claiming Woolmer was murdered because he "knew a lot" about the Cronje affair and posed a risk to fixers.[37][38] He argued these incidents underscored the need for the International Cricket Council (ICC) to act decisively, including deploying undercover officials to trap participants and imposing stringent penalties to eradicate the issue.[34] Regarding the handling of scandals, Rice criticized the response to Cronje's exposure, stating in a 2013 interview that "the whole thing was handled badly," while predicting in April 2000 that the revelations would indelibly taint South African cricket.[33][39] He also revealed personal encounters, noting that as a national selector he had been approached to fix matches but reported the overtures to the ICC two to three years prior to 2010, emphasizing that the game's reputation risked driving away sponsors unless addressed urgently.[38] Rice's views positioned match fixing not merely as corruption but as an existential peril to cricket's integrity and participants' safety.Critiques of post-apartheid transformation policies

Clive Rice expressed strong opposition to the United Cricket Board of South Africa's (UCB) post-apartheid transformation policies, which mandated quotas for non-white players in domestic and international selections to promote racial equity. He argued that these measures prioritized political goals over cricketing merit, eroding the quality of teams and prompting talented players to emigrate. In a 2002 statement, Rice described the policy of forcing clubs to field black players as "damaging the domestic competition, and as a consequence the national team," specifically criticizing the selection of Justin Ontong over Jacques Rudolph for a Test match against Australia to meet a quota of two non-white players.[40] He emphasized meritocracy, stating, "Whether you are black or white you would want to get there on merit and not be used as a political soccer ball."[40] Rice further contended that such interventions created incompatibilities between transformation targets and competitive success. In early 2002, he urged South African players to revolt against the system, declaring, "The brutal truth ... is that the goals of transformation and the goals of winning are not compatible."[41] By 2004, he labeled the approach "inverted racism," warning it mirrored Zimbabwe's decline by driving away white players and stifling overall development, potentially turning South Africa into a cricketing pariah state.[42] Rice advocated for organic growth through investment in schoolboy and grassroots cricket rather than enforced quotas, asserting that evidence from youth levels showed no inherent need for such mandates, as they instead caused harm by undermining selection integrity.[43] His critiques extended to long-term impacts, including the exodus of players like Kevin Pietersen, who cited racial quotas as a factor in leaving South Africa in 2003; Pietersen subsequently joined Nottinghamshire under Rice's coaching. Rice reiterated these concerns as late as 2015, claiming quotas were "hurting" South Africa's World Cup prospects by compromising team strength.[44] Throughout, Rice maintained that while redressing apartheid-era exclusions was valid, coercive policies risked reversing gains in sporting excellence, a view he voiced amid broader debates on balancing equity with performance in post-1994 South African sports governance.[7]Illness and death

Clive Rice was diagnosed with a brain tumour in early 2015.[26] He travelled to Bangalore, India, in March 2015 for radiation treatment.[14] Despite these efforts, his condition deteriorated, leading to his admission to a hospital in Cape Town.[26] [4] Rice died on 28 July 2015, five days after his 66th birthday, from complications arising from the brain tumour.[26] [14] [29] His death was confirmed by his family and Cricket South Africa, with tributes highlighting his resilience as a fighter both on and off the field.[45]Legacy and assessments

Cricketing achievements and records

Clive Rice amassed 26,331 first-class runs at an average of 40.95, including 48 centuries and 137 half-centuries, across 482 matches spanning 1969 to 1994.[8][46] He also claimed 930 wickets at a bowling average of 22.49, demonstrating his prowess as an all-rounder. In List A cricket, Rice featured in 479 matches, underscoring his extensive domestic involvement.[1] Domestically, Rice captained Transvaal—nicknamed the "Mean Machine"—to multiple Currie Cup triumphs, contributing to ten title wins for the province over two decades during his career.[47][6] He led Nottinghamshire to their first County Championship since 1929 in 1981, following a double victory in limited-overs and first-class competitions the previous year.[9][7] Rice's leadership extended to standout individual performances, such as twin unbeaten centuries in a single first-class match for Nottinghamshire, a feat achieved by only the second batsman in county history.[8] Internationally, Rice captained South Africa in their return to official cricket, leading the team in three ODIs against India in November 1991, where he scored 26 runs at an average of 13.00 and took 2 wickets at 57.00.[1][23] He played no official Test matches due to South Africa's sporting isolation under apartheid. Rice received the Wisden Cricketer of the Year award in 1981 for his instrumental role in Nottinghamshire's success and overall all-round contributions.[48] He was also named South African Cricket Annual Cricketer of the Year in 1971, 1985, and 1986.[8]| Format | Matches | Runs | Avg | 100s/50s | Wickets | Bowl Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-class | 482 | 26,331 | 40.95 | 48/137 | 930 | 22.49 |

| List A | 479 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ODIs | 3 | 26 | 13.00 | 0/0 | 2 | 57.00 |

Debates on apartheid associations

Clive Rice's cricketing career coincided with South Africa's apartheid era, during which the national team was isolated from international competition from 1970 to 1991 due to the regime's racial policies, limiting his opportunities to domestic play for Transvaal and county cricket in England.[49] He participated as a player and often captain in unofficial Test matches against rebel touring sides from Australia, England, and other nations in the 1980s, series that defied the global boycott intended to pressure the apartheid government.[4] These engagements, funded in part by South African authorities, drew criticism for undermining anti-apartheid efforts by providing sporting legitimacy and spectacle to the isolated regime, with detractors labeling Rice an apologist who prioritized personal and professional gain over moral opposition.[4] [13] Rice offered no public condemnation of apartheid's segregation in sport or society during its duration, a silence that commentators have interpreted as tacit acceptance of the system that excluded non-white players from representative cricket while enabling his dominance in all-white provincial teams like Transvaal's "Mean Machine."[50] [51] In a 2010 interview, he later described South African players as "lumbered with SA’s ridiculous apartheid laws," framing the era's restrictions as an imposition rather than a system he actively challenged, and noted facing protests abroad but emphasized resilience over resistance.[13] Critics, including post-apartheid analysts, have accused him of defending white privilege in South African sport and failing to advocate for non-white development, portraying his legacy as flawed by complicity in a racially stratified structure that benefited white athletes exclusively.[51] [13] Post-apartheid, Rice's selection as South Africa's captain for their 1991 return to international cricket—debuting against India on November 13, 1991—signaled broad acceptance within the sport, with figures like Kepler Wessels praising him as the leader to emerge from isolation.[29] [4] However, his subsequent critiques of transformation policies intensified debates; in 2004, he decried quotas and affirmative action in cricket selection as "apartheid in reverse" and "inverted racism," arguing they prioritized racial redress over merit, drove white players "out in droves," and risked emulating Zimbabwe's decline by sidelining talent.[42] [52] As manager of the United Cricket Board's development academy in 1995, he emphasized excellence and performance metrics over demographic targets, clashing with mandates for racial representation.[51] Defenders contend these positions reflected a commitment to competitive standards amid rapid policy shifts, not racial animus, noting Rice's lack of overt prejudice toward non-white colleagues and his own victimization by the boycott, which denied him Test matches during his prime from 1975 to 1990.[17] [49] Yet, opponents view his resistance to quotas—implemented to rectify apartheid's exclusion of black, coloured, and Indian players—as perpetuating structural advantages, with some labeling him a bigot whose on-field prowess overshadowed ethical shortcomings.[51]References

- https://www.[espncricinfo](/page/ESPNcricinfo).com/cricketers/clive-rice-46976