Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classical Kuiper belt object

View on Wikipedia

|

A classical Kuiper belt object, also called a cubewano (/ˌkjuːbiːˈwʌnoʊ/ "QB1-o"),[a] is a low-eccentricity Kuiper belt object (KBO) that orbits beyond Neptune and is not controlled by an orbital resonance with Neptune. Cubewanos have orbits with semi-major axes in the 40–50 AU range and, unlike Pluto, do not cross Neptune's orbit. That is, they have low-eccentricity and sometimes low-inclination orbits like the classical planets.

The name "cubewano" derives from the first trans-Neptunian object (TNO) found after Pluto and Charon: 15760 Albion, which until January 2018 had only the provisional designation (15760) 1992 QB1.[2] Similar objects found later were often called "QB1-os", or "cubewanos", after this object, though the term "classical" is much more frequently used in the scientific literature.

Objects identified as cubewanos include:

- 15760 Albion[3] (aka 1992 QB1 and gave rise to the term "Cubewano")

- 136472 Makemake, a dwarf planet[3]

- 50000 Quaoar and 20000 Varuna, each considered the largest TNO at the time of discovery[3]

- 19521 Chaos, 58534 Logos, 53311 Deucalion, 66652 Borasisi, 88611 Teharonhiawako

- (33001) 1997 CU29, (55636) 2002 TX300, 55565 Aya, 55637 Uni

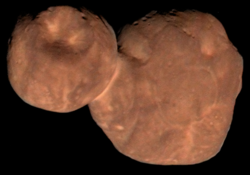

- 486958 Arrokoth

136108 Haumea was provisionally listed as a cubewano by the Minor Planet Center in 2006,[4] but was later found to be in a resonant orbit.[3]

Orbits: 'hot' and 'cold' populations

[edit]There are two basic dynamical classes of classical Kuiper-belt bodies: those with relatively unperturbed ('cold') orbits, and those with markedly perturbed ('hot') orbits.

Most cubewanos are found between the 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune (populated by plutinos) and the 1:2 resonance. 50000 Quaoar, for example, has a near-circular orbit close to the ecliptic. Plutinos, on the other hand, have more eccentric orbits bringing some of them closer to the Sun than Neptune.

The majority of classical objects, the so-called cold population, have low inclinations (< 5°) and near-circular orbits, lying between 42 and 47 AU. A smaller population (the hot population) is characterised by highly inclined, more eccentric orbits.[5] The terms 'hot' and 'cold' has nothing to do with surface or internal temperatures, but rather refer to the orbits of the objects, by analogy to molecules in a gas, which increase their relative velocity as they heat up.[6]

The Deep Ecliptic Survey reports the distributions of the two populations; one with the inclination centered at 4.6° (named Core) and another with inclinations extending beyond 30° (Halo).[7]

Distribution

[edit]The vast majority of KBOs (more than two-thirds) have inclinations of less than 5° and eccentricities of less than 0.1 . Their semi-major axes show a preference for the middle of the main belt; arguably, smaller objects close to the limiting resonances have been either captured into resonance or have their orbits modified by Neptune.

The 'hot' and 'cold' populations are strikingly different: more than 30% of all cubewanos are in low inclination, near-circular orbits. The parameters of the plutinos’ orbits are more evenly distributed, with a local maximum in moderate eccentricities in 0.15–0.2 range, and low inclinations 5–10°. See also the comparison with scattered disk objects.

Cubewanos form a clear 'belt' outside Neptune's orbit, whereas the plutinos approach, or even cross Neptune's orbit. When orbital inclinations are compared, 'hot' cubewanos can be easily distinguished by their higher inclinations, as the plutinos typically keep orbits <20°. The high inclination of 'hot' cubewanos has not been explained.[8]

Cold and hot populations: physical characteristics

[edit]In addition to the distinct orbital characteristics, the two populations display different physical characteristics.

The difference in colour between the red cold population, such as 486958 Arrokoth, and more heterogeneous hot population was observed as early as in 2002.[9] Recent studies, based on a larger data set, indicate the cut-off inclination of 12° (instead of 5°) between the cold and hot populations and confirm the distinction between the homogenous red cold population and the bluish hot population.[10]

Another difference between the low-inclination (cold) and high-inclination (hot) classical objects is the observed number of binary objects. Binaries are quite common on low-inclination orbits and are typically similar-brightness systems. Binaries are less common on high-inclination orbits and their components typically differ in brightness. This correlation, together with the differences in colour, support further the suggestion that the currently observed classical objects belong to at least two different overlapping populations, with different physical properties and orbital history.[11]

Toward a formal definition

[edit]There is no official definition of 'cubewano' or 'classical KBO'. However, the terms are normally used to refer to objects free from significant perturbation from Neptune, thereby excluding KBOs in orbital resonance with Neptune (resonant trans-Neptunian objects). The Minor Planet Center (MPC) and the Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES) do not list cubewanos (classical objects) using the same criteria. Many TNOs classified as cubewanos by the MPC, such as dwarf planet Makemake, are classified as ScatNear (possibly scattered by Neptune) by the DES. (119951) 2002 KX14 may be an inner cubewano near the plutinos. Furthermore, there is evidence that the Kuiper belt has an 'edge', in that an apparent lack of low-inclination objects beyond 47–49 AU was suspected as early as 1998 and shown with more data in 2001.[12] Consequently, the traditional usage of the terms is based on the orbit's semi-major axis, and includes objects situated between the 2:3 and 1:2 resonances, that is between 39.4 and 47.8 AU (with exclusion of these resonances and the minor ones in-between).[5]

These definitions lack precision: in particular the boundary between the classical objects and the scattered disk remains blurred. As of 2023[update], there are 870 objects with perihelion (q) > 40 AU and aphelion (Q) < 48 AU.[13]

DES classification

[edit]Introduced by the report from the Deep Ecliptic Survey by J. L. Elliott et al. in 2005 uses formal criteria based on the mean orbital parameters.[7] Put informally, the definition includes the objects that have never crossed the orbit of Neptune. According to this definition, an object qualifies as a classical KBO if:

- it is not resonant

- its average Tisserand's parameter with respect to Neptune exceeds 3

- its average eccentricity is less than 0.2.

SSBN07 classification

[edit]An alternative classification, introduced by B. Gladman, B. Marsden and C. van Laerhoven in 2007, uses a 10-million-year orbit integration instead of the Tisserand's parameter. Classical objects are defined as not resonant and not being currently scattered by Neptune.[14]

Formally, this definition includes as classical all objects with their current orbits that

- are non-resonant (see the definition of the method)

- have a semi-major axis greater than that of Neptune (30.1 AU; i.e. excluding centaurs) but less than 2000 AU (to exclude inner-Oort-cloud objects)

- are not being scattered by Neptune

- have their eccentricity (to exclude detached objects)

Unlike other schemes, this definition includes the objects with major semi-axis less than 39.4 AU (2:3 resonance)—termed inner classical belt, or more than 48.7 (1:2 resonance) – termed outer classical belt, and reserves the term main classical belt for the orbits between these two resonances.[14]

Families

[edit]The first known collisional family in the classical Kuiper belt—a group of objects thought to be remnants from the breakup of a single body—is the Haumea family.[15] It includes Haumea, its moons, 2002 TX300 and seven smaller bodies.[b] The objects not only follow similar orbits but also share similar physical characteristics. Unlike many other KBO their surface contains large amounts of water ice (H2O) and no or very little tholins.[16] The surface composition is inferred from their neutral (as opposed to red) colour and deep absorption at 1.5 and 2. μm in infrared spectrum.[17] Several other collisional families might reside in the classical Kuiper belt.[18][19]

Exploration

[edit]

As of January 2019, only one classical Kuiper belt object has been observed up close by spacecraft. Both Voyager spacecraft have passed through the region before the discovery of the Kuiper belt.[20] New Horizons was the first mission to visit a classical KBO. After its successful exploration of the Pluto system in 2015, the NASA spacecraft has visited the small KBO 486958 Arrokoth at a distance of 3,500 kilometres (2,200 mi) on 1 January 2019.[21]

List

[edit]Here is a very generic list of classical Kuiper belt objects. As of July 2023[update], there are about 870 objects with q > 40 AU and Q < 48 AU.[13]

- 15760 Albion

- 20000 Varuna

- 307261 Máni

- (307616) 2003 QW90

- (444030) 2004 NT33

- (308193) 2005 CB79

- (119951) 2002 KX14

- (120178) 2003 OP32

- 120347 Salacia

- (144897) 2004 UX10

- 145452 Ritona

- (145453) 2005 RR43

- 148780 Altjira

- (15807) 1994 GV9

- (16684) 1994 JQ1

- 174567 Varda

- (19255) 1994 VK8

- 19521 Chaos

- (202421) 2005 UQ513

- (24835) 1995 SM55

- (24978) 1998 HJ151

- (278361) 2007 JJ43

- (33001) 1997 CU29

- 486958 Arrokoth

- 50000 Quaoar

- (52747) 1998 HM151

- 53311 Deucalion

- 55565 Aya

- (55636) 2002 TX300

- 55637 Uni

- 58534 Logos

- 66652 Borasisi

- (69987) 1998 WA25

- 79360 Sila–Nunam

- (79983) 1999 DF9

- (85627) 1998 HP151

- (85633) 1998 KR65

- (86047) 1999 OY3

- 88611 Teharonhiawako

- 90568 Goibniu

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Somewhat old-fashioned, but "cubewano" is still used by the Minor Planet Center for their list of Distant Minor Planets.[1]

- ^ As of 2008. The four brightest objects of the family are situated on the graphs inside the circle representing Haumea.[clarification needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Distant Minor Planets".

- ^ Jewitt, David. "Classical Kuiper Belt Objects". UCLA. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Brian G. Marsden (30 January 2010). "MPEC 2010-B62: Distant Minor Planets (2010 FEB. 13.0 TT)". IAU Minor Planet Center. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "MPEC 2006-X45: Distant Minor Planets". IAU Minor Planet Center & Tamkin Foundation Computer Network. 12 December 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ a b Jewitt, D.; Delsanti, A. (2006). "The Solar System Beyond The Planets" (PDF). Solar System Update : Topical and Timely Reviews in Solar System Sciences (PDF). Springer-Praxis. ISBN 978-3-540-26056-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2006.)

- ^ Levison, Harold F.; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2003). "The formation of the Kuiper belt by the outward transport of bodies during Neptune's migration". Nature. 426 (6965): 419–421. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..419L. doi:10.1038/nature02120. PMID 14647375. S2CID 4395099.

- ^ a b J. L. Elliot; et al. (2006). "The Deep Ecliptic Survey: A Search for Kuiper Belt Objects and Centaurs. II. Dynamical Classification, the Kuiper Belt Plane, and the Core Population". Astronomical Journal. 129 (2): 1117–1162. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.1117E. doi:10.1086/427395. ("Preprint" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2006.)

- ^ Jewitt, D. (2004). "Plutino". Archived from the original on 19 April 2007.

- ^ A. Doressoundiram; N. Peixinho; C. de Bergh; S. Fornasier; P. Thebault; M. A. Barucci; C. Veillet (October 2002). "The Color Distribution in the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt". The Astronomical Journal. 124 (4): 2279. arXiv:astro-ph/0206468. Bibcode:2002AJ....124.2279D. doi:10.1086/342447. S2CID 30565926.

- ^ Peixinho, Nuno; Lacerda, Pedro; Jewitt, David (August 2008). "Color-inclination relation of the classical Kuiper belt objects". The Astronomical Journal. 136 (5): 1837. arXiv:0808.3025. Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1837P. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/5/1837. S2CID 16473299.

- ^ K. Noll; W. Grundy; D. Stephens; H. Levison; S. Kern (April 2008). "Evidence for two populations of classical transneptunian objects: The strong inclination dependence of classical binaries". Icarus. 194 (2): 758. arXiv:0711.1545. Bibcode:2008Icar..194..758N. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.10.022. S2CID 336950.

- ^ Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Brown, Michael E. (2001). "The Radial Distribution of the Kuiper Belt" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 554 (1): L95 – L98. Bibcode:2001ApJ...554L..95T. doi:10.1086/320917. S2CID 7982844. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2006.

- ^ a b "q > 40 AU and Q < 48 AU". IAU Minor Planet Center. minorplanetcenter.net. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b Gladman, B. J.; Marsden, B.; van Laerhoven, C. (2008). "Nomenclature in the Outer Solar System" (PDF). In Barucci, M. A.; et al. (eds.). The Solar System Beyond Neptune. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2755-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-02.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Barkume, Kristina M.; Ragozzine, Darin; Schaller, Emily L. (2007). "A collisional family of icy objects in the Kuiper belt" (PDF). Nature. 446 (7133): 294–6. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..294B. doi:10.1038/nature05619. PMID 17361177. S2CID 4430027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-23.

- ^ Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Brunetto, R.; Licandro, J.; Gil-Hutton, R.; Roush, T. L.; Strazzulla, G. (2009). "The surface of (136108) Haumea (2003 EL61), the largest carbon-depleted object in the trans-Neptunian belt". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 496 (2): 547. arXiv:0803.1080. Bibcode:2009A&A...496..547P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200809733. S2CID 15139257.

- ^ Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Licandro, J.; Gil-Hutton, R.; Brunetto, R. (2007). "The water ice rich surface of (145453) 2005 RR43: a case for a carbon-depleted population of TNOs?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 468 (1): L25 – L28. arXiv:astro-ph/0703098. Bibcode:2007A&A...468L..25P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077294. S2CID 18546361.

- ^ Chiang, E.-I. (July 2002). "A Collisional Family in the Classical Kuiper Belt". The Astrophysical Journal. 573 (1): L65 – L68. arXiv:astro-ph/0205275. Bibcode:2002ApJ...573L..65C. doi:10.1086/342089. S2CID 18671789.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (11 February 2018). "Dynamically correlated minor bodies in the outer Solar system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 474 (1): 838–846. arXiv:1710.07610. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.474..838D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2765. S2CID 73588205.

- ^ Stern, Alan (28 February 2018). "The PI's Perspective: Why Didn't Voyager Explore the Kuiper Belt?". Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (24 January 2018). "New Horizons prepares for encounter with 2014 MU69". Planetary Society. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

External links

[edit]- Jewitt, David. "Kuiper belt site". UCLA.

- "The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter".

- "List of Trans-Neptunian objects", IAU Minor Planet Center, minorplanetcenter.org, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, archived from the original on 27 August 2010

- "TNO pages". johnstonarchive.net.

- "Plot of the current positions of bodies in the Outer Solar System". IAU Minor Planet Center. minorplanetcenter.org. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Classical Kuiper belt object

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

Orbital Criteria

Classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) are defined as non-resonant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with perihelion distances AU and semi-major axes AU.[6] These parameters ensure the objects maintain orbits exterior to Neptune's influence without entering mean-motion resonances.[1] They typically possess low orbital eccentricities (median ) and low inclinations, with the cold population exhibiting and the hot population inclinations up to .[1][7] These characteristics distinguish classical KBOs from more dynamically excited populations. The criteria explicitly exclude resonant objects, such as Plutinos locked in the 2:3 mean-motion resonance with Neptune at approximately 39.4 AU, as well as scattered disk objects with high eccentricities ().[7] The term "classical" originated from early Kuiper Belt models proposed by David Jewitt and Jane Luu in the 1990s, reflecting orbits akin to the primordial, unperturbed structure envisioned in foundational theories.[8]Distinction from Other Trans-Neptunian Objects

Classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) are distinguished from resonant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) primarily by their lack of mean-motion resonance with Neptune. Resonant TNOs, such as Plutinos in the 3:2 resonance, exhibit clustered orbital libration due to Neptune's gravitational influence, which stabilizes their orbits but ties them to specific semi-major axis values (e.g., around 39.4 AU for Plutinos). In contrast, classical KBOs occupy non-resonant orbits with semi-major axes typically between 42 and 48 AU, experiencing minimal resonant perturbations that allow for a broader, more uniformly distributed range of eccentricities and inclinations.[9] Unlike scattered disk objects (SDOs), which display highly eccentric orbits (e > 0.2) and semi-major axes exceeding 50 AU, often extending to hundreds of AU due to repeated close encounters with Neptune, classical KBOs maintain lower eccentricities (e < 0.2) and inclinations (i ≲ 30°), reflecting limited dynamical excitation. SDOs originate from scattering events during Neptune's migration or ongoing perturbations, leading to perihelia (q) greater than 30 AU but with unstable, diffusion-like evolution, whereas classical KBOs' orbits remain dynamically stable over billions of years.[10] Detached objects represent another distinct subclass, characterized by perihelia exceeding 40 AU (q > 40 AU) and semi-major axes beyond Neptune's 2:1 resonance (a > 48 AU), without evidence of current scattering or resonance. These objects, such as Sedna, differ from classical KBOs by their greater detachment from planetary influences, possibly arising from external perturbations like a passing star, a rogue planet, or an unseen massive body in the outer solar system, rather than the in-situ formation and stability that define classical KBOs.[11] Within the Kuiper Belt's overall structure, classical KBOs constitute the "main belt," a relatively undisturbed region that preserves the primordial planetesimal disk from the solar system's formation approximately 4.6 billion years ago. Their low-eccentricity and low-inclination orbits serve as separators from other TNO subclasses, highlighting minimal perturbations from Neptune and enabling insights into the early dynamical environment.[12]Orbital Populations

Cold Population Characteristics

The cold population of classical Kuiper belt objects consists of non-resonant trans-Neptunian objects with low orbital inclinations (typically i < 5°), low eccentricities (e ≲ 0.1), and semi-major axes in the range of 42–48 AU, which collectively form a thin, disk-like structure closely aligned with the ecliptic plane.[13] These parameters define a dynamically quiescent subset that avoids significant scattering by Neptune.[14] The cold and hot populations are typically separated at an inclination of ~5°. This population exhibits a concentrated distribution near the ecliptic plane, with a notably higher spatial density in the inner Kuiper Belt compared to outer regions, reflecting their limited vertical and radial dispersion over billions of years.[7] Their orbital configuration results in minimal close encounters with Neptune, ensuring long-term dynamical stability and preserving these objects as remnants of the primordial planetesimal disk that formed in situ beyond 42 AU. As such, the cold population is widely regarded as the least processed component of the Kuiper Belt, offering direct insights into early Solar System conditions with little alteration from giant planet migrations.[15] Estimates from dedicated surveys, including the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS; 2013–2018), indicate a total population of approximately 100,000 cold classical objects with diameters greater than 50 km, based on debiased observations of their absolute magnitude distribution and size-frequency relation.[16] In contrast to the hot population's broader inclinations exceeding 5°, the cold population's tight orbital clustering underscores its isolation from disruptive dynamical influences.[7]Hot Population Characteristics

The hot population of classical Kuiper belt objects is distinguished by its dynamically excited orbits, featuring inclinations greater than ~5° and extending up to 30°, eccentricities in the range of approximately 0.05 to 0.15, and semi-major axes between 42 and 48 AU.[17] These parameters lead to a more vertically dispersed distribution, contrasting with the low-inclination, nearly coplanar configuration of the cold population.[18] The broader spread in inclinations suggests that hot classical objects were likely implanted into their current orbits from the scattered disk or more distant regions during the early dynamical evolution of the outer Solar System.[15] Their excited orbital elements provide evidence of stirring induced by the migration of the giant planets, consistent with simulations from the Nice model that reproduce the observed structure through planetary instabilities occurring hundreds of millions of years after Solar System formation.[19] Estimates indicate the hot population comprises a significant fraction of the classical belt, with around 50,000–100,000 objects with diameters exceeding 50 km as of 2021, subject to higher discovery biases owing to their wider sky coverage and visibility in surveys.[20]Physical Properties

Size and Albedo Variations

Classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) exhibit a broad range of sizes, from sub-kilometer particles to rare large bodies exceeding 1,000 km in diameter, such as Quaoar with an estimated diameter of about 1,100 km. For objects in the 10–100 km diameter range, the differential size distribution follows a power-law form with index –4, characterized by a steep drop-off in the abundance of larger bodies. This distribution shows a natural cutoff around 1,000 km, reflecting the limited reservoir of material available for forming such massive objects in the classical belt.[21][22][23] Geometric albedos among classical KBOs vary from roughly 0.05 to 0.20, with larger objects tending toward the lower end of this range due to potentially thicker regoliths or resurfacing effects. The cold population averages higher albedos at about 0.15, compared to around 0.10 for the hot population, a distinction that may arise from differences in surface processing or volatile retention. These albedo variations introduce detection biases in optical surveys, as brighter (higher-albedo) objects are more readily observed, potentially overrepresenting the cold population relative to its true abundance.[24][25] The combined size and albedo distributions yield a total mass estimate for the classical Kuiper belt of approximately 0.01–0.1 Earth masses, with the bulk residing in small bodies owing to the power-law steepness. Elevated albedos in the cold population lower mass estimates for that subgroup to around 0.001 Earth masses. Additionally, the binary fraction stands at about 30% for cold classical KBOs, markedly higher than in the hot population, indicating formation in a dynamically quiescent environment that preserved wide-separation pairs.[26][24][24]Compositional and Color Differences

Classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) display distinct spectral types that reflect differences in surface materials and processing histories between the cold and hot populations. The cold population predominantly exhibits neutral red colors, characterized by B-V indices around 1.0, indicative of irradiation-processed organics dominating their spectra.[27] In contrast, the hot population tends toward bluer hues, with g-r colors approximately 0.6 compared to about 0.8 for the cold population, suggesting less extensive reddening from cosmic ray exposure or different compositional starting points.[27] These color variations are measured across optical and near-infrared wavelengths, where cold classical KBOs often show steeper spectral slopes (S' > 25% per 100 nm) consistent with ultra-red surfaces.[28] Surface compositions of classical KBOs are primarily mixtures of water ice and complex organics, with variations tied to object size and dynamical history. Water ice is ubiquitous, appearing as crystalline forms with absorption features at 1.5 and 2.0 μm, particularly on mid-sized bodies (500–1200 km diameter) where it forms a detectable substrate. Complex organics, such as tholins—refractory polymers formed by irradiation of methane and other volatiles—contribute to the red coloration, especially in the cold population where methanol ice retention beyond 20 AU enhances organic processing. Methane ice is retained primarily on larger bodies (>1500 km), like Pluto and Eris, appearing patchy or absent on smaller classical KBOs due to volatile loss over time; the cold population preserves more volatiles overall, including methanol, compared to the hotter, more processed hot population. For example, the cold classical KBO 486958 Arrokoth shows methanol-dominated ices without prominent water ice, alongside tholin-like organics from radiolytic processing of simple molecules. A notable color-inclination correlation exists within the classical KBO populations, particularly among hot objects, where higher inclinations correspond to bluer colors. This trend, with bluer hot classical KBOs (lower spectral slopes) at inclinations >10°, implies these objects were scattered from an inner protoplanetary disk region with different irradiation or compositional environments.[29] Such scattering models explain the relative blueness as arising from less organic buildup in warmer, inner disk materials before outward migration.[30] Recent James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations from 2023 to 2025 have provided high-resolution near-infrared spectra confirming diverse ices on small classical KBOs, including water ice, carbon dioxide, methanol, and carbon monoxide on objects akin to Arrokoth.[31] These findings reveal a rich molecular diversity, with water-ice absorption bands positively correlating with size and methanol processing yielding sugar-like organics under galactic cosmic ray exposure, supporting primordial compositions in the cold population.Classification Schemes

DES Classification

The Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES), conducted from 2003 to 2009, established a dynamical classification scheme for trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) based on numerical orbital integrations to distinguish stable populations from those influenced by Neptune's resonances or scattering.[32] Classical Kuiper belt objects are defined in this scheme as non-resonant cubewanos, characterized by semimajor axes between approximately 42 and 48 AU, time-averaged eccentricities less than 0.2, and mean Tisserand parameters with respect to Neptune exceeding 3, indicating minimal perturbation.[32] To ensure stability, DES employed 10 million-year forward integrations of three test orbits (nominal and ±3σ in semimajor axis uncertainty), requiring all to remain in the same dynamical class with semimajor axis uncertainties below 10% for secure classification.[32] Within the classical category, DES subdivided objects into cold and hot populations based on orbital inclination, reflecting distinct dynamical histories. The cold population features low inclinations (typically i < 5°), forming a tight kernel with low eccentricities and inclinations concentrated near the ecliptic plane, while the hot population exhibits higher inclinations (i > 5°) and is further distinguished by a stirred component with elevated eccentricities and inclinations, suggesting external excitation.[32] These subdivisions exclude objects with higher eccentricities or those captured in mean-motion resonances (e.g., 3:2 or 2:1 with Neptune), which are classified separately.[32] The DES framework was refined by Gladman et al. in 2008 through extended nomenclature for outer solar system objects, incorporating longer integrations and improved resonance detection, which reclassified some DES scattered objects as resonant and identified 263 classical KBOs from a sample of 584 TNOs.[33] This refinement formalized the cold/hot split at i ≈ 5° and emphasized kernel (low e/i) versus stirred (higher e/i) distinctions within classicals.[33] However, the 10 Myr simulation timescale in DES overlooks long-term chaotic instabilities from high-order resonances or secular perturbations, leading to potential misclassifications of marginally stable objects.[32] Subsequent analyses using Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS) data after 2018 and the DECam Ecliptic Exploration Project (DEEP) since 2023 have addressed these limitations by incorporating debiased samples and extended dynamical modeling to better constrain classical stability.[14][34] The DES scheme shows partial overlap with the SSBN07 classification in population splits, particularly for cold/hot divisions, but prioritizes simulation-based stability over statistical clustering.[33]SSBN07 Classification

The SSBN07 classification scheme, detailed in a chapter by Kavelaars et al. (2008), employs a statistical approach to delineate subpopulations within the classical Kuiper belt using hierarchical clustering of orbital elements. This method analyzes the semi-major axis (a), eccentricity (e), inclination (i), and longitude of the ascending node (Ω) of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) to identify distinct groups without relying on dynamical simulations. By applying agglomerative clustering, it separates the low-inclination, tightly clustered "cold" population—characterized by i < 5° and e < 0.1, representing minimal excitation—from the higher-inclination, more dispersed "hot" population with i up to ~15°, reflecting underlying differences in dynamical histories.[35] This clustering drew primarily from the Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES) with ~217 secure detections and early data from the Canada-France Ecliptic Plane Survey (CFEPS). The approach's data-driven nature offers advantages over simulation-based methods, as it directly leverages observational biases and requires no assumptions about long-term stability.[35] Validation of the SSBN07 scheme comes from correlations with physical properties, such as color distributions, where hot population objects exhibit bluer spectra compared to the redder cold population, supporting the dynamical separation. This aligns with DES stability tests, which confirm the cold group's long-term orbital coherence. Subsequent integrations with DES classifications and modern surveys like OSSOS and DEEP have refined the scheme; as of 2023, the JPL Small-Body Database catalogs approximately 870 classical Kuiper belt objects with perihelion >40 AU and aphelion <48 AU amenable to this clustering, with numbers exceeding 900 by 2025.[35]Dynamical Families

Haumea Family

The Haumea family represents the largest and most prominent collisional family identified among classical Kuiper belt objects, originating from a catastrophic collision involving the dwarf planet Haumea approximately 3–4 billion years ago. This event produced fragments that share similar orbital elements, with semi-major axes around 43 AU and inclinations near 28°, indicative of their dynamical linkage to the hot classical population. The collision is modeled as a high-velocity impact that disrupted a water-ice-rich mantle, ejecting icy debris while preserving Haumea's elongated shape and rapid rotation. Simulations of the family's dynamical evolution over gigayears demonstrate that the fragments' tight clustering in orbital space could only result from a relatively recent (post-Neptune migration) disruption, with survival rates of 60–75% after 4 Gyr of evolution under gravitational influences.[36][37] Key members include Haumea itself, with an equivalent diameter of approximately 1,600 km, and its two known satellites, Hi'iaka (diameter ~160 km) and Namaka (~150 km), which are thought to be captured remnants or co-formed ejecta from the same collision. Beyond these, around 10 larger fragments (diameters 70–365 km) such as 2002 TX300 and 2009 YE2 have been dynamically confirmed through orbital similarity (Δv < 300 m s⁻¹), while spectroscopic and photometric surveys have identified up to ~70 smaller candidates based on shared neutral colors and water-ice signatures. These small fragments, often with absolute magnitudes H > 10, extend the family's size distribution, revealing a steep cumulative slope consistent with collisional grinding over billions of years.[38] Family members exhibit distinctive physical characteristics, including high geometric albedos ranging from 0.5 to 0.8—among the highest in the Kuiper belt—attributed to exposed crystalline water ice surfaces free of dark organics. Their near-infrared spectra show strong absorption features at 1.5 and 2.0 μm due to pure water ice, contrasting with the redder, lower-albedo spectra of non-family classical KBOs. This icy composition links the family to Haumea's differentiated interior, where the collision stripped away a volatile mantle, and aligns with their affiliation to the dynamically excited hot population, characterized by higher inclinations and moderate eccentricities.[39][40] Recent orbital integrations from 2023–2025, incorporating data from surveys like OSSOS and Pan-STARRS, have reinforced the dynamical connections among confirmed members while identifying no new large (D > 100 km) objects, suggesting the family's initial mass was dominated by Haumea and a few major fragments. These studies, using N-body simulations over 4 Gyr, confirm the stability of the core group's clustering and rule out significant interloper contamination, with newly verified members like 2014 QA442 extending the velocity dispersion slightly beyond prior limits (~300 m s⁻¹). Follow-up near-infrared observations of candidates continue to prioritize water-ice confirmation, highlighting the family's role as a snapshot of ancient collisional processes in the outer solar system.[41]Other Identified Families

Besides the prominent Haumea collisional family, several tentative dynamical and collisional families have been proposed within the classical Kuiper belt population, identified through statistical clustering in proper orbital elements such as semi-major axis, eccentricity, and inclination. These methods detect overdensities of objects that exceed expected background levels, often supplemented by similarities in surface colors or spectra to suggest a common origin from disruptions. For instance, one early candidate family, proposed as the first in the Kuiper belt, consists of approximately 32 objects with low free inclinations around 2° and semi-major axes clustered between 44 and 45 AU, potentially fragments from a parent body at least 800 km in diameter disrupted by a collision.[42] As of November 2025, no additional collisional families beyond Haumea have been firmly confirmed in the classical Kuiper belt, though tentative clusters continue to be investigated using data from surveys like OSSOS. These proposed families typically involve smaller objects with diameters under 200 km and are thought to stem from collisions within the last 1 Gyr, preserving tight orbital groupings due to the low dynamical excitation in the classical belt. Their detection underscores the role of past impacts in sculpting the belt's structure, providing evidence for ongoing collisional processing despite the region's relative stability over billions of years.[43]Formation and Evolution

Primordial Formation Theories

The primordial formation of classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) primarily occurred in the outer regions of the solar system's protoplanetary disk, where mechanisms like the streaming instability enabled the transition from dust and ice particles to kilometer-sized planetesimals. In this model, at heliocentric distances of approximately 40–50 AU, turbulent gas flows in the disk caused solids—primarily icy pebbles—to concentrate aerodynamically, leading to gravitational instabilities and rapid clumping into planetesimals. This process, driven by differential drift between gas and solids, efficiently formed these bodies in a relatively quiescent environment before significant dynamical perturbations.[44] The cold classical KBO subpopulation, characterized by low-inclination orbits, is interpreted as largely in situ remnants of this early accretion phase, with implications for the disk's low total mass limiting object sizes. Simulations indicate that the solid disk mass in this region was only about 0.05 Earth masses—roughly a few percent of the minimum-mass solar nebula—allowing high-efficiency planetesimal formation but capping maximum diameters at around 100 km due to insufficient material for larger gravitational accretion. This low-mass environment favored the survival of a dynamically cold population without substantial growth into planetary embryos. Recent models suggest disk substructures during protoplanetary disk dissipation could form multiple dynamical classes of planetesimals in situ.[45] Additionally, studies of ultrawide binaries in the cold population indicate they may form later through dynamical processes rather than during primordial accretion, challenging aspects of streaming instability outcomes.[46] The presence of volatile ices played a crucial role in enabling this formation beyond the water snow line, where frozen H₂O and other condensates boosted the disk's solid surface density by factors of 10–100 compared to inner regions, promoting particle sticking and growth to pebble sizes suitable for streaming instability. However, the outward radial drift of these icy particles, induced by gas drag, or their scattering by migrating giant planets, halted further collisional accretion, preserving a relic population of small, ice-rich bodies rather than allowing runaway growth.[47] Observational evidence, such as the uniform red colors of cold classical KBOs, supports these models by matching predictions from protoplanetary disk chemistry, where ultraviolet irradiation and thermal processing of organic ices produced complex reddish hydrocarbons preserved since formation. These spectral properties, distinct from other dynamical classes, indicate minimal post-formation alteration and consistency with in situ disk origins.[48]Dynamical Processing Models

The Nice model posits that a dynamical instability among the giant planets approximately 4 billion years ago scattered planetesimals from the outer protoplanetary disk, implanting the hot classical Kuiper belt population into the region between Neptune's 3:2 and 2:1 mean motion resonances (roughly 42–48 AU). In this scenario, Neptune's orbit reaches high eccentricity (e ≈ 0.3) during the instability, creating a chaotic diffusion region within its outer mean motion resonances that captures and transports objects originally located interior to approximately 35 AU from the primordial planetesimal disk.[19] These scattered planetesimals form the dynamically excited hot population, characterized by higher inclinations (i > 5°) and eccentricities (e ≈ 0.1), while distinguishing them from the lower-excitation cold classical objects.[49] Key excitation mechanisms for the hot classical orbits involve secular resonances induced by the migrating planets, particularly during the depletion of the solar nebula and Neptune's orbital evolution. Sweeping secular resonances, primarily driven by Jupiter's gravitational perturbations, raise inclinations to root-mean-square values of approximately 11° and eccentricities to about 0.1 in the hot group, as these resonances pass through the classical belt over timescales of 10–100 million years. In contrast, the cold classical population remains preserved in stable, low-eccentricity zones exterior to Neptune's influence, avoiding significant excitation from these resonances or direct planetary scattering.[50] Near mean motion resonances like the 2:1 with Neptune, secular forcing accelerates eccentricity growth, but rapid damping of Neptune's eccentricity limits overlap with the cold belt to prevent its disruption.[50] Simulations of giant planet migration reveal that the primordial planetesimal disk underwent extreme depletion, with approximately 99% of its mass lost through ejection to interstellar space, implantation into the scattered disk, or transfer to the Oort cloud. Kaib and Sheppard (2009) demonstrated this sensitivity using N-body integrations, showing that variations in migration timing and planetesimal distribution lead to final classical belt masses of only 0.01–0.1 Earth masses, consistent with observed populations. The surviving hot classical objects thus represent a small fraction of the original disk, dynamically mixed from inner and outer sources during the instability.[19] Recent refinements to these models, incorporating the Planet Nine hypothesis, suggest that a distant super-Earth-mass planet (5–10 M⊕ at 400–800 AU) could further shape the hot population through long-term secular perturbations, enhancing clustering in perihelion arguments and orbital poles among high-inclination objects.[51] Batygin et al. (2024) explored how Planet Nine generates low-inclination, Neptune-crossing trans-Neptunian objects via resonance capture and eccentricity modulation, providing a mechanism to sustain observed alignments in the outer hot classical belt without requiring additional instabilities.[51] These integrations, building on earlier Nice model outputs, indicate that Planet Nine's gravitational torque could detach perihelia (q > 40 AU) and align orbits over billions of years, refining predictions for the hot population's structure.[52]Exploration and Observations

Ground-Based Surveys

Ground-based surveys have been instrumental in discovering and characterizing the population of classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs), which are non-resonant trans-Neptunian objects with low eccentricities and semi-major axes between approximately 42 and 48 AU. These surveys employ wide-field imaging to detect faint, slow-moving targets against the starry background, typically using large-aperture telescopes equipped with CCD detectors to achieve limiting magnitudes around V ≈ 24–25. Follow-up astrometry over multiple nights or seasons is essential to refine orbital elements, distinguishing classical KBOs from resonant or scattered populations.[32] The Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES), operating from 1998 to 2005 on 4-m telescopes at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory and Kitt Peak National Observatory, systematically searched the ecliptic plane and discovered over 500 trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), providing the first large, bias-characterized sample for dynamical classification and revealing the distinction between low-inclination "cold" and higher-inclination "hot" classical subpopulations.[32][53] Subsequent efforts like the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), conducted from 2013 to 2018 using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT), focused on multiple ecliptic blocks to probe orbital structure with well-defined pointing biases. OSSOS discovered over 100 classical KBOs as part of its 838 total TNO detections, enabling precise modeling of the size distribution and inclination biases through a dedicated survey simulator. Similarly, the Dark Energy Survey (DES), spanning 2013 to 2019 with the 4-m Victor M. Blanco Telescope, serendipitously identified 316 TNOs in its first four years alone, including numerous classical KBOs, and applied bias corrections via simulations to derive debiased luminosity functions and size estimates for the population.[14][54] These surveys, supplemented by wide-field instruments on facilities like Subaru Telescope, have collectively cataloged approximately 900 known classical KBOs as of 2025, with recent 2023–2024 Subaru observations adding dozens of small cold classical objects (diameters ≲ 50 km) through targeted searches in the ecliptic plane. Observational biases in magnitude-limited searches preferentially detect hot classical KBOs, as their higher inclinations (i ≳ 5°) project them over larger sky volumes compared to low-inclination cold objects; this is mitigated by synthetic population injections and simulator-based corrections to recover intrinsic distributions.[55]Spacecraft Encounters

The New Horizons spacecraft achieved the first close-range encounter with a classical Kuiper belt object (KBO) during its flyby of (486958) Arrokoth on January 1, 2019, at a distance of approximately 3,500 km.[56] Arrokoth, classified as a cold classical KBO due to its low-eccentricity, low-inclination orbit, measures about 35 km in its longest dimension and exhibits a contact binary structure, with two distinct lobes—a larger, flatter one (Wenu) and a smaller, rounder one (Weeyo)—joined by a narrow neck suggestive of a gentle merger in the early solar system.[57] Observations confirmed its extremely red surface coloration, redder than Pluto, attributed to complex organic tholins formed from irradiation of primordial ices.[56] Post-flyby analyses of data collected by New Horizons' instruments, including the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) and the Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array (LEISA), have profoundly impacted understanding of classical KBO formation and evolution. The object's bulk density is estimated at 235 kg/m³ (approximately 0.235 g/cm³), with a 1σ uncertainty range of 155–600 kg/m³, indicating a highly porous, rubble-pile interior akin to loosely packed snow and consistent with minimal post-formation processing.[58] Studies from 2020 to 2025 have refined its three-dimensional shape model, identified geologic features such as the "Sky Crater" as a compaction site rather than an impact scar, and mapped surface units revealing a pristine, unweathered regolith preserved since the solar nebula era. These findings underscore Arrokoth's role as a "time capsule" for cold classical KBOs, supporting models of binary formation through gravitational collapse of pebble clouds in the protoplanetary disk. Prior to New Horizons, Voyager 1 provided the earliest spacecraft perspectives on the Kuiper Belt region through its 1990 "Family Portrait" imaging campaign, capturing mosaics from about 40 AU that included views toward the belt's inner edge, though without resolving individual classical KBOs or yielding specific details on their properties.[59] No dedicated missions to classical KBOs are presently planned beyond New Horizons' ongoing extended operations, which include remote sensing of the Kuiper Belt environment until the spacecraft exits the region around 2028–2029.[60] The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time, commencing full operations in 2025, will enhance precursor discoveries by detecting thousands of KBOs, including cold classicals, to inform potential future flyby targets.[61]Notable Examples

Key Objects and Their Properties

Classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) exhibit a range of sizes, orbital parameters, and surface compositions that provide insights into the primordial disk from which they formed. Among the largest non-resonant classical KBOs, 50000 Quaoar stands out with a diameter of 1100 km, determined from thermal infrared observations.[62] Its orbit features a semi-major axis of 43.7 AU, low eccentricity of 0.039, and inclination of 7.98°, placing it in the hot classical subpopulation characterized by moderate inclinations greater than about 5°. Quaoar's surface shows evidence of crystalline water ice and methane absorptions at 1.72 μm and 2.2 μm, indicating exposure to temperatures above 35 K in the past, possibly through cryovolcanic activity; a thin methane atmosphere with pressure less than 1 microbar has been constrained by stellar occultation observations. It also hosts a satellite, Weywot, with a diameter of about 165 km, orbiting at 14,500 km separation, allowing density estimates of 1.75 g/cm³ for the system. Another prominent hot classical KBO is 20000 Varuna, with a diameter of 900 km. Its orbit has a semi-major axis of 43.1 AU, eccentricity of 0.056, and higher inclination of 17.2°. Varuna displays a red color (spectral slope of 22% per 0.1 μm) and a geometric albedo of 0.07, suggesting a surface rich in complex organics rather than fresh ices; it rotates rapidly with a period of 6.34 hours, potentially indicating a collisional history. No confirmed satellites are known, but its density is estimated at around 0.9–2.3 g/cm³ based on assumed compositions.[63] Binaries are common among classical KBOs, offering clues to formation via gravitational capture in the dense planetesimal disk. A classic example is 1998 WW31, a cold classical binary with components of diameters approximately 150 km and 130 km, measured via Hubble Space Telescope imaging of their relative orbit. The primary orbit has a semi-major axis of 43.3 AU, eccentricity of 0.214, and low inclination of 5.16°. The two components orbit each other with high eccentricity (≈0.8) and a period of 570 days at a separation of about 6,500 km, implying a total system density of roughly 1.3 g/cm³; the surface appears neutral in color, consistent with water ice and minimal processing. Other notable hot classical KBOs include 2002 AW197 (700 km diameter, albedo 0.17, a=47.4 AU, i=24.4°, neutral color possibly with water ice) and 2002 UX25 (659 km, albedo 0.092, a=42.8 AU, e=0.139, i=19.5°, binary, water ice, neutral).[64] The following table summarizes properties of selected key classical KBOs, focusing on the largest and most studied examples, with sizes primarily from space-based thermal and direct imaging (Spitzer, Herschel, HST, ALMA, JWST):| Object | Diameter (km) | Albedo | a (AU) | e | i (°) | Class | Key Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50000 Quaoar | 1100 | 0.124 | 43.7 | 0.039 | 7.98 | Hot | Methane ice, binary (Weywot), red |

| 20000 Varuna | 900 | 0.07 | 43.1 | 0.056 | 17.2 | Hot | Red organics, rapid rotator |

| 2002 AW197 | 700 | 0.17 | 47.4 | 0.132 | 24.4 | Hot | Neutral, possible water ice |

| 2003 AZ84 | - | - | - | - | - | - | Removed: Plutino, not classical |

| 2002 UX25 | 659 | 0.092 | 42.8 | 0.139 | 19.5 | Hot | Binary, water ice, neutral |

| 2005 QU182 | 580 | 0.15 | 42.9 | 0.094 | 5.4 | Cold | Red, low inclination |

| 1998 WW31 | ~140 (system) | 0.069 | 43.3 | 0.214 | 5.16 | Cold | Eccentric binary orbit, neutral |

| 2013 FY27 | - | - | - | - | - | - | Removed: SDO, not classical |