Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Lists of astronomical objects.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lists of astronomical objects

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Selection of astronomical bodies and objects:

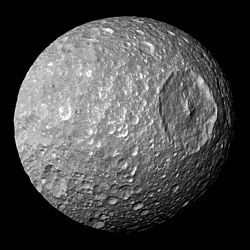

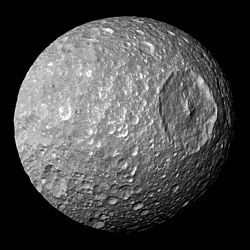

- Moon Mimas and Ida, an asteroid with its own moon, Dactyl

- Comet Lovejoy and Jupiter, a giant gas planet

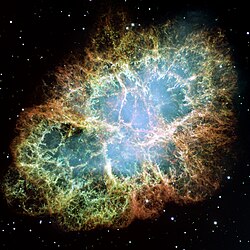

- The Sun; Sirius A with Sirius B, a white dwarf; the Crab Nebula, a remnant supernova

- A black hole (artist concept); Vela Pulsar, a rotating neutron star

- M80, a globular cluster, and the Pleiades, an open star cluster

- The Whirlpool Galaxy and Abell 2744, a galaxy cluster

- Superclusters, galactic filaments and voids

This is a list of lists, grouped by type of astronomical object.

Solar System

[edit]- List of Solar System objects

- List of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System

- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun

- List of Solar System objects by size

- Lists of geological features of the Solar System

- List of natural satellites (moons)

- Lists of small Solar System bodies

- Lists of comets

- List of meteor showers

- Minor planets

Exoplanets, exomoons, and brown dwarfs

[edit]- Lists of planets

- List of nearest exoplanets

- List of largest exoplanets

- List of smallest exoplanets

- List of directly imaged exoplanets

- List of exoplanet extremes

- List of exoplanet firsts

- List of exoplanets discovered by the Kepler space telescope

- List of exoplanets observed during Kepler's K2 mission

- List of hottest exoplanets

- List of coolest exoplanets

- List of proper names of exoplanets

- List of exomoon candidates

- List of brown dwarfs

- List of rogue planets

Stars and star systems

[edit]- Lists of stars

- List of brightest stars

- List of hottest stars

- List of coolest stars

- List of nearest bright stars

- List of most luminous stars

- List of most massive stars

- List of largest stars

- List of stars with resolved images

- List of smallest stars

- List of oldest stars

- List of stars with proplyds

- List of variable stars

- List of X-ray pulsars

- List of brown dwarfs

- List of white dwarfs

- List of multiplanetary systems

Lists of stars by distance

[edit]- List of nearest stars (from 0ly to 20ly)

- List of star systems within 20–25 light-years

- List of star systems within 25–30 light-years

- List of star systems within 30–35 light-years

- List of star systems within 35–40 light-years

- List of star systems within 40–45 light-years

- List of star systems within 45–50 light-years

- List of star systems within 50–55 light-years

- List of star systems within 55–60 light-years

- List of star systems within 60–65 light-years

- List of star systems within 65–70 light-years

- List of star systems within 70–75 light-years

- List of star systems within 75–80 light-years

- List of star systems within 80–85 light-years

- List of star systems within 85–90 light-years

- List of star systems within 90–95 light-years

- List of star systems within 95–100 light-years

- List of star systems within 100–150 light-years

- List of star systems within 150–200 light-years

- List of star systems within 200–250 light-years

- List of star systems within 250–300 light-years

- List of star systems within 300–350 light-years

- List of star systems within 350–400 light-years

- List of star systems within 400–450 light-years

- List of star systems within 450–500 light-years

- List of most distant stars

Lists of stars by luminosity

[edit]Supernovae

[edit]Star constellations

[edit]Star clusters

[edit]Nebulae

[edit]Galaxies

[edit]- Satellite galaxies

Galaxy groups and clusters

[edit]Black holes

[edit]Other lists

[edit]- List of voids

- List of largest cosmic structures

- List of the most distant astronomical objects

- List of neutron stars

- List of most massive neutron stars

- List of least massive black holes

- List of resolved circumstellar disks

- List of brightest natural objects in the sky

- List of gravitational wave observations

- List of star-forming regions in the Local Group

Astronomical catalogues

[edit]Galaxies

[edit]Nebulae

[edit]Stars

[edit]Exoplanets

[edit]Map of astronomical objects

[edit]See also

[edit]Lists of astronomical objects

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Solar System

Planets and Dwarf Planets

The Solar System's eight planets are diverse in size, composition, and orbital characteristics, orbiting the Sun in a flattened disk. The inner four—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—are terrestrial planets with rocky surfaces, primarily composed of silicate rocks and metals, and relatively thin atmospheres (or none, in Mercury's case). Their diameters range from 4,879 km for Mercury to 12,756 km for Earth, with masses varying from 3.30 × 10²³ kg (Mercury) to 5.97 × 10²⁴ kg (Earth); orbital periods span 88 Earth days for Mercury to 687 Earth days for Mars.[10][11] The outer four—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—are giant planets, divided into gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) with thick atmospheres dominated by hydrogen (about 90%) and helium (about 10%), and ice giants (Uranus and Neptune) enriched in water, ammonia, and methane ices beneath hydrogen-helium envelopes. Jupiter, the largest, has an equatorial diameter of 142,984 km and a mass of 1.90 × 10²⁷ kg, with an orbital period of 11.86 Earth years; Saturn measures 120,536 km in diameter and 5.68 × 10²⁶ kg in mass, orbiting every 29.46 Earth years; Uranus is 51,118 km in diameter and 8.68 × 10²⁵ kg, with a 84.02-year orbit; Neptune spans 49,528 km and weighs 1.02 × 10²⁶ kg, completing its orbit in 164.8 Earth years.[10][12] Dwarf planets, as defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in Resolution B5 at the 2006 General Assembly, are solar-orbiting bodies massive enough for their own gravity to form a nearly spherical shape (hydrostatic equilibrium), neither satellites nor having gravitationally cleared their orbital paths of other objects. The IAU recognizes five such bodies: Ceres (discovered January 1, 1801, by Giuseppe Piazzi; diameter 946 km), Pluto (discovered February 18, 1930, by Clyde Tombaugh; diameter 2,377 km), Haumea (discovered December 28, 2004, by a team led by José Luis Ortiz Moreno; elongated shape ~1,600 km × 1,000 km), Makemake (discovered March 31, 2005, by Michael Brown's team; diameter ~1,430 km), and Eris (discovered January 5, 2005, by Brown's team; diameter 2,326 km). These are primarily icy bodies in the asteroid belt (Ceres) or Kuiper Belt/Scattered Disk (the others), with compositions rich in water ice, frozen methane, and rocky cores.[13][14] The following table summarizes key orbital parameters for the planets and dwarf planets, including semi-major axis (in astronomical units, AU), orbital eccentricity, and sidereal orbital period (in Earth years unless noted). Data reflect heliocentric orbits relative to the ecliptic.[10]| Body | Semi-major Axis (AU) | Eccentricity | Orbital Period (Earth years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.3871 | 0.2056 | 0.2408 (88 days) |

| Venus | 0.7233 | 0.0068 | 0.6152 (225 days) |

| Earth | 1.0000 | 0.0167 | 1.0008 |

| Mars | 1.5237 | 0.0934 | 1.8808 |

| Ceres | 2.7672 | 0.0758 | 4.607 |

| Jupiter | 5.2026 | 0.0489 | 11.862 |

| Saturn | 9.5549 | 0.0555 | 29.457 |

| Uranus | 19.2184 | 0.0444 | 84.011 |

| Neptune | 30.1104 | 0.0086 | 164.80 |

| Pluto | 39.482 | 0.2488 | 247.68 |

| Haumea | 43.134 | 0.1949 | 283.28 |

| Makemake | 45.430 | 0.1588 | 305.60 |

| Eris | 67.780 | 0.4407 | 557.28 |

Natural Satellites and Rings

Natural satellites, commonly known as moons, are naturally occurring celestial bodies that orbit planets, ranging from small rocky fragments to large icy worlds with subsurface oceans. In the Solar System, these objects number over 890 confirmed moons (as of November 2025), predominantly around the gas and ice giants, where their dynamical properties—such as tidal locking, where a moon's rotation period matches its orbital period to always show the same face to its host planet—reveal insights into gravitational interactions and formation processes. Discoveries began with telescopic observations in the 17th century and accelerated through spacecraft missions like Voyager and Cassini, enabling detailed studies of compositions dominated by ice, rock, and volatiles. Recent advancements, including the confirmation of 128 new moons around Saturn in March 2025 and a new moon (S/2025 U1) for Uranus in August 2025, continue to expand these catalogs.[15][16][17] Earth's single natural satellite, the Moon, has a diameter of 3,474 kilometers and is tidally locked, resulting from gravitational tides that synchronized its rotation over billions of years. Its composition features a basaltic crust rich in silicates and oxides, an olivine-pyroxene mantle, and an iron-rich core, with the surface marked by ancient impact basins and maria formed by volcanic activity around 3-4 billion years ago. Known to humanity since prehistoric times, the Moon's dynamical stability influences Earth's axial tilt and ocean tides.[18] Jupiter hosts 95 known moons, with the four Galilean satellites—discovered by Galileo Galilei on January 7, 1610, using an early telescope—standing out for their size and diversity. Io (3,643 km diameter) is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System due to intense tidal heating from orbital resonances with its siblings, featuring a sulfur-rich surface with over 400 active volcanoes. Europa (3,122 km) exhibits a cracked icy exterior, potentially concealing a global subsurface ocean of liquid water sustained by tidal flexing, and is tidally locked like the others. Ganymede (5,268 km), the Solar System's largest moon, possesses a layered structure of surface ice, subsurface ocean, rocky mantle, and metallic core, generating its own magnetic field amid tidal locking. Callisto (4,821 km), the outermost Galilean moon, shows a heavily cratered, ancient icy crust with minimal geological activity and is also tidally locked, orbiting beyond the intense tidal influences on its inner counterparts. These moons' resonant orbits maintain dynamical stability, preventing orbital decay.[19] Saturn boasts 274 confirmed moons (as of March 2025), far exceeding other planets, with many exhibiting tidal locking and resonances that sculpt their orbits. Titan, discovered by Christiaan Huygens on March 25, 1655, is the second-largest moon in the Solar System at 5,150 km in diameter and unique for its dense nitrogen-methane atmosphere thicker than Earth's, fostering lakes of liquid methane and ethane on an icy surface rich in organics, driven by tidal and radiative processes. Other prominent regular satellites include Rhea (1,528 km, predominantly water ice with a thin oxygen exosphere), Iapetus (1,470 km, featuring a stark equatorial ridge and two-toned coloration from dust transfer in its orbit), and Enceladus (504 km, an icy world with cryovolcanic plumes of water vapor from a subsurface ocean, powered by tidal heating). These moons' prograde, low-eccentricity orbits suggest formation from a circumplanetary disk, with tidal interactions maintaining alignment.[16] Uranus has 29 known moons (as of August 2025), five of which are large classical satellites discovered between 1787 and 1986, all tidally locked and orbiting in Uranus's equatorial plane due to the planet's extreme axial tilt. Titania (1,578 km diameter), identified by William Herschel in 1787, is the largest with an icy, rocky composition showing faulted terrains and possible cryovolcanic past. Oberon (1,523 km), also discovered by Herschel in 1787, displays a cratered surface with bright rays, indicative of retained impact ejecta on its ice-rock mix. Ariel (1,158 km) and Umbriel (1,169 km), found by William Lassell in 1851, feature Ariel's youthful, canyon-riddled canyons suggesting recent resurfacing and Umbriel's darker, ancient craters on similar icy compositions. Miranda (472 km), imaged by Voyager 2 in 1986, is the smallest major moon yet geologically dramatic, with Verona Rupes cliffs up to 20 km high possibly from tidal disruption or impacts, its surface a patchwork of icy terrains. Dynamical models indicate these moons accreted from a disk tilted by Uranus's obliquity.[20][17][21] Neptune's 16 moons include the massive Triton, discovered by William Lassell on October 10, 1846, just 17 days after Neptune itself. At 2,707 km in diameter, Triton is tidally locked in synchronous rotation but follows a retrograde orbit inclined 157 degrees to Neptune's equator, a signature of capture that subjects it to strong tidal dissipation, driving its orbital decay at about 3.5 cm per year. Composed of a frozen nitrogen crust over a water-ammonia ocean and rocky core, with density twice that of pure ice, Triton exhibits geysers of nitrogen plumes and a thin atmosphere, its dynamical evolution suggesting it disrupted Neptune's original satellite system upon capture from the Kuiper Belt. Smaller inner moons like Proteus (420 km) are irregular and co-orbital, shaped by tidal resonances.[22] Planetary ring systems are vast, flat disks of orbiting debris, primarily water ice particles, whose dynamical properties—such as density waves from satellite perturbations—govern their structure and evolution. Saturn's rings, glimpsed by Galileo in 1610 and fully resolved by Huygens in 1655, extend to 282,000 km from the planet but are only 10-30 meters thick, comprising seven main divisions (D, C, B, A, F, G, E) labeled by discovery order. The dense B ring, the brightest, has optical depths of 0.5-2.5, indicating high particle density, while the translucent C ring shows tau ≈ 0.05-0.2; particles range from micrometer dust to 10-meter chunks, mostly pure ice with rocky cores, shepherded by moons like Prometheus into gaps like the 4,700-km-wide Cassini Division. Uranus's 13 faint rings, discovered via stellar occultations in 1977 and imaged by Voyager 2 in 1986, are narrow and dark, composed of water ice and organics with particle sizes from micrometers to centimeters, exhibiting low optical depths (10^{-6} to 10^{-3}) and eccentric shapes maintained by embedded moonlets. Neptune's four rings, plus arcs in the Adams ring, detected by Voyager 2 in 1989, contain dark, reddish dust and ice particles up to several centimeters, with optical depths around 10^{-3} to 0.1, dynamically confined by resonances with inner moons like Galatea. Jupiter's tenuous rings, discovered by Voyager 1 in 1979, are faint dusty structures fed by volcanic ejecta from Io, with micron-sized particles and negligible optical depth. These systems' particle dynamics reflect ongoing collisional grinding and Poynting-Robertson drag, limiting their ages to hundreds of millions of years.[23][24][25] Beyond regular satellites formed in circumplanetary disks, irregular satellites—small, distant moons comprising over 100 objects across the giant planets—exhibit highly eccentric (e > 0.2) and inclined (i > 20°) orbits, hallmarks of capture from heliocentric paths rather than in situ accretion. Grouped into prograde and retrograde families (e.g., Jupiter's Pasiphae and Carme clans), these bodies, typically 1-200 km in diameter with dark, carbonaceous compositions akin to asteroids or Kuiper Belt objects, are thought captured during the early Solar System's dynamical instability, possibly via three-body encounters, temporary gas drag in a dissipating nebula, or tidal stripping of larger parent bodies. Numerical simulations support capture efficiencies during planetary migration, with post-capture circularization incomplete due to weak tides at large distances, explaining their vulnerability to ejection by perturbers like passing comets.[26]| Planet | Major Regular Moons (Examples) | Key Dynamical Property | Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | Moon (3,474 km) | Tidally locked | Prehistoric |

| Jupiter | Io (3,643 km), Europa (3,122 km), Ganymede (5,268 km), Callisto (4,821 km) | Orbital resonances; tidal heating | 1610 (Galileo) |

| Saturn | Titan (5,150 km), Rhea (1,528 km), Iapetus (1,470 km) | Prograde disk formation; resonances | 1655 (Huygens) for Titan |

| Uranus | Miranda (472 km), Ariel (1,158 km), Umbriel (1,169 km), Titania (1,578 km), Oberon (1,523 km) | Equatorial alignment; tidal locking | 1787-1986 |

| Neptune | Triton (2,707 km) | Retrograde capture orbit; tidal decay | 1846 (Lassell) |

Minor Planets and Comets

Minor planets, encompassing asteroids and centaurs, represent a diverse population of rocky and icy bodies in the Solar System, primarily orbiting between Mars and Neptune, with comprehensive catalogs maintained by the Minor Planet Center.[27] Asteroids are predominantly found in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, while centaurs occupy unstable orbits crossing those of the outer planets, exhibiting hybrid characteristics of asteroids and comets due to their icy compositions and occasional activity.[28] Observational lists track over a million known minor planets, classified by orbital parameters, size, and composition to aid in understanding Solar System formation. The main asteroid belt contains the majority of known asteroids, with the four largest—1 Ceres, 4 Vesta, 2 Pallas, and 10 Hygiea—accounting for about half the belt's total mass. Ceres, the largest at approximately 946 km in diameter, is classified as a G-type asteroid in the Tholen system, indicative of carbonaceous material rich in hydrous silicates.[29] Vesta, around 525 km across, belongs to the rare V-type, featuring a basaltic crust from early differentiation and volcanism.[30] Pallas, measuring about 512 km, is a B-type asteroid with a primitive, chondritic-like composition, while Hygiea, at roughly 407 km, is a C-type, dominated by carbon-rich organics.[31][32] These spectral types, derived from reflectance spectra, reveal compositional gradients across the belt, from volatile-rich outer regions to drier inner zones. The belt's distribution shows prominent Kirkwood gaps, regions depleted of asteroids at semi-major axes corresponding to mean-motion resonances with Jupiter, such as the 3:1 resonance at 2.5 AU, where gravitational perturbations destabilize orbits over time, ejecting material or increasing eccentricities.[33][34] Beyond the main belt, Jupiter's Trojan asteroids cluster at the L4 and L5 Lagrange points, sharing Jupiter's orbit in stable tadpole or horseshoe configurations, with over 10,000 known members providing insights into early Solar System dynamics.[35] Near-Earth asteroids (NEAs), including the Apollo group, have orbits intersecting or approaching Earth's, posing potential collision risks; the Apollo asteroids specifically have semi-major axes greater than 1 AU and perihelia less than 1.017 AU, with examples like 1862 Apollo itself.[36] Among these, 99942 Apophis, a 370-meter S-type asteroid, is classified as potentially hazardous due to its close approach in 2029 at just 31,000 km from Earth, though impact probability is now negligible at less than 1 in 150,000.[37] Centaurs, numbering around 500 cataloged objects, bridge the main belt and Kuiper Belt with perihelia beyond Jupiter and aphelia inside Neptune, often displaying cometary outbursts from sublimating ices.[28] Comets, distinct yet related to minor planets through shared icy origins, are cataloged separately by the Minor Planet Center based on orbital periods and dynamical histories.[27] Periodic comets have orbits under 200 years, often influenced by Jupiter, while long-period comets exceed this threshold with highly eccentric paths.[38] Halley's Comet (1P/Halley), the archetypal periodic comet, has an orbital period of approximately 76 years, returning predictably since ancient records, with its retrograde orbit linking it to the scattered disk.[39] In contrast, long-period comets originate primarily from the Oort Cloud, a distant spherical reservoir perturbed by passing stars, whereas short-period ones, including many periodic types, hail from the Kuiper Belt's scattered population.[40] Notable long-period examples include C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp), the Great Comet of 1997, which reached perihelion in April 1997 with a nucleus about 60 km across and remained visible to the naked eye for 18 months, offering unprecedented study of cometary chemistry.[41] These lists enable tracking of cometary evolution, from reservoir depletion to active fragmentation near the Sun.Interplanetary Dust and Meteoroids

Interplanetary dust consists of tiny particles, typically ranging from micrometers to millimeters in size, distributed throughout the Solar System and primarily originating from cometary disintegration and asteroid collisions.[42] These particles scatter sunlight, producing observable phenomena such as the zodiacal light, a faint, diffuse band of light visible along the ecliptic plane shortly after sunset or before sunrise.[43] The zodiacal light arises from the forward scattering of sunlight by dust particles concentrated in the interplanetary medium, with its brightness peaking near the ecliptic due to the higher spatial density of dust in that plane. Models of the dust distribution indicate that the number density follows a profile that increases toward the ecliptic, influenced by the gravitational dynamics and radiation pressure acting on particles from sources like comets.[44] Closely related to the zodiacal light is the gegenschein, a brighter patch of light visible opposite the Sun in the night sky, resulting from the opposition surge effect where backscattered sunlight from dust particles aligns optimally at 180 degrees elongation.[45] Observations confirm that the gegenschein's morphology correlates with the spatial density variations in the interplanetary dust cloud, particularly its enhancement near the ecliptic plane.[44] Both phenomena provide key data for mapping the overall structure of the dust distribution, which thins out with increasing distance from the Sun but maintains a pronounced concentration within about 10 degrees of the ecliptic.[43] Meteoroids, the solid components of interplanetary dust larger than typical dust grains (often centimeters or smaller), form streams when ejected material from parent bodies follows orbital paths that intersect Earth's orbit at predictable times.[42] These streams produce annual meteor showers, with notable examples including the Perseids, associated with comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, peaking around August 12–13 with a radiant in the constellation Perseus at approximately right ascension 48° and declination +58°. The Leonids, linked to comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, reach their peak on November 17–18, emanating from a radiant in Leo at right ascension 152° and declination +22°, typically yielding about 15 meteors per hour under ideal conditions. Similarly, the Geminids, originating from the asteroid 3200 Phaethon, peak on December 13–14 from a radiant in Gemini at right ascension 112° and declination +33°, often producing up to 120 meteors per hour and recognized as one of the most intense annual showers. Beyond organized streams, sporadic meteors and micrometeorites constitute the background population of interplanetary debris not tied to specific parent bodies, observed at a baseline flux of 5 to 8 meteors per hour across the sky from Earth-based vantage points.[42] NASA's meteor observation networks, such as the All-Sky Fireball and Bolide Network, have measured sporadic meteor fluxes varying seasonally by up to a factor of two, with higher rates in the latter half of the year due to orbital inclinations favoring encounters with prograde material.[49] Micrometeorites, the smallest subset (under 2 mm), contribute to a continuous influx detected by spacecraft instruments, with flux rates on the order of 10^{-6} to 10^{-4} particles per square meter per second at 1 AU, primarily influencing atmospheric entry and planetary surface accretion.[50]Nearby Stellar Neighborhood

Stars Within 20 Light-Years

The immediate stellar neighborhood within 20 light-years (approximately 6.13 parsecs) of the Sun encompasses a compact volume containing 94 known stellar systems, including 130 stars, brown dwarfs, and substellar objects, as compiled in the Fifth Catalogue of Nearby Stars (CNS5) using astrometric data primarily from the Gaia Early Data Release 3 (EDR3).[51] This catalog provides high-precision parallaxes for these objects, enabling accurate distance measurements with typical uncertainties below 1% for the nearest systems.[51] The majority of these stars are low-mass red dwarfs of spectral types M0 to M8, reflecting the initial mass function's preference for low-mass stars in the solar vicinity, with only a handful of brighter, more massive examples like Sirius and Procyon.[51] The nearest star system is the Alpha Centauri triple, located 4.37 light-years away, consisting of Alpha Centauri A (G2V, Sun-like), Alpha Centauri B (K1V, orange dwarf), and the closer Proxima Centauri (M5.5Ve, red dwarf) at 4.24 light-years, which is the closest individual star to the Sun.[52] Proxima Centauri hosts the potentially habitable exoplanet Proxima b, orbiting in the habitable zone. Barnard's Star, a red dwarf (M4.0V) at 5.96 light-years, exhibits the highest known proper motion of any star, traversing 10.3 arcseconds per year across the sky.[51] Sirius, at 8.58 light-years, is the brightest star in Earth's night sky (apparent magnitude -1.46) and a binary system with a white dwarf companion, while Luyten's Star (also known as GJ 273, M3.5V) lies 12.35 light-years away and features a candidate habitable-zone planet.[51] These systems illustrate the diversity of the local stellar population, dominated by cool, dim M dwarfs but punctuated by more luminous F- and G-type stars. Parallax measurements from the Gaia mission have revolutionized the mapping of this volume, confirming and refining distances for all known objects within 20 light-years with sub-milliarcsecond precision in many cases.[52] The CNS5 integrates Gaia EDR3 parallaxes with supplementary data from Hipparcos and ground-based surveys to achieve near-complete volume-limited coverage down to magnitude G=19.[51] Below is a table of selected prominent stars and systems within this radius, ordered by distance, highlighting key examples with their Gaia-derived distances (in light-years), spectral types, and apparent visual magnitudes (V); full details for all 130 objects are available in the CNS5.[51]| Star/System | Distance (ly) | Spectral Type | Apparent Magnitude (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proxima Centauri | 4.24 | M5.5Ve | 11.13 |

| Alpha Centauri A | 4.37 | G2V | -0.01 |

| Alpha Centauri B | 4.37 | K1V | 1.33 |

| Barnard's Star | 5.96 | M4.0V | 9.54 |

| Wolf 359 | 7.86 | M6.0V | 13.54 |

| Lalande 21185 | 8.31 | M2.0V | 7.49 |

| Sirius A | 8.58 | A1Vm | -1.46 |

| Sirius B | 8.58 | DA2 | 8.44 |

| Luyten 726-8 A (BL Ceti) | 8.73 | M5.5Ve | 12.54 |

| Luyten 726-8 B (UV Ceti) | 8.73 | M6.0Ve | 12.99 |

| Ross 154 | 9.68 | M3.5V | 10.44 |

| Ross 248 | 10.32 | M5.5V | 12.29 |

| Epsilon Eridani | 10.52 | K2V | 3.73 |

| Lacaille 9352 | 10.74 | M0.5V | 7.34 |

| Ross 128 | 11.01 | M4.0V | 11.13 |

| EZ Aquarii A | 11.11 | M5.0V | 12.66 |

| EZ Aquarii B | 11.11 | M5.0V | ~13.0 |

| EZ Aquarii C | 11.11 | M5.0V | ~13.0 |

| Procyon A | 11.46 | F5IV-V | 0.34 |

| Procyon B | 11.46 | DA | 10.7 |

| Sigma Draconis | 18.82 | G9IV | 4.67 |

| Groombridge 34 A | 11.62 | M1.0V | 8.14 |

| Groombridge 34 B | 11.62 | M3.5V | 10.88 |

Stars 20–100 Light-Years Away

The region between 20 and 100 light-years from the Sun encompasses an expanding sample of the solar neighborhood, where surveys reveal a diverse array of stellar types amenable to detailed observations with ground- and space-based telescopes. The REsearch Consortium on Nearby Stars (RECONS) has cataloged the 100 nearest star systems, with many falling in this intermediate distance range up to approximately 68 light-years, providing precise parallaxes, proper motions, and photometry for over 250 objects within 32.6 light-years alone, and extending insights to fainter members beyond.[53] These efforts highlight the dominance of low-mass stars, with red dwarfs (M-type) comprising about 75% of all stars in the local volume, underscoring their prevalence in the Milky Way's stellar population.[54] Prominent examples in the 20–50 light-year subgroup include Vega (Alpha Lyrae), a rapidly rotating A0V main-sequence star at 25 light-years, renowned for its surrounding debris disk detected via infrared excess, indicative of ongoing planetesimal collisions.[55] Similarly, Fomalhaut (Alpha Piscis Austrini), an A3V star also at 25 light-years, hosts a complex debris disk with three nested belts extending to 14 billion miles, imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope and shaped by unseen planetary influences.[56] Further out, in the 50–100 light-year range, evolved giants like Arcturus (Alpha Boötis) at 37 light-years—a K0III red giant with 170 times the Sun's luminosity—and Capella (Alpha Aurigae) at 42 light-years, a binary system of a G3III giant and an F0III subgiant, exemplify brighter, more massive stars that outshine the faint red dwarf majority. Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri), a K5III orange giant at 65 light-years, adds to this with its prominent position in Taurus, though not part of the Hyades cluster. Membership in young moving groups within this zone is determined through high proper motions—typically exceeding 100 mas/year—and matching radial velocities, which trace co-moving stellar associations born from the same molecular cloud. The Beta Pictoris moving group, with an age of about 20–25 million years, includes over 20 members at distances of 40–90 light-years, such as Beta Pictoris itself at 63 light-years, a young A6V star with a prominent edge-on debris disk observed by Hubble.[57] These groups, identified via astrometric data from Gaia, offer windows into early stellar evolution and planet formation, distinct from the denser, more distant clusters.[58]Stars 100–500 Light-Years Away

The stars situated 100 to 500 light-years from the Sun form an important segment of the Galactic disk's local structure, bridging the well-mapped solar neighborhood and more distant stellar populations. This distance range includes a mix of main-sequence stars, giants, and supergiants, whose positions and motions contribute to models of the Milky Way's kinematics and chemical evolution. Observations in this interval reveal increasing influence from the interstellar medium, including dust lanes that obscure fainter objects.[59] Key historical catalogs have facilitated systematic listing of these stars. The Hipparcos Catalogue, released by the European Space Agency in 1997, measured parallaxes for 118,218 stars, enabling distance estimates accurate to within 10-20% for objects up to several hundred light-years, particularly the brighter ones visible to the naked eye. Complementing this, the Gaia mission's Data Release 3 (DR3) from 2022 provides astrometric data for over 1.8 billion sources, with geometric distances derived from parallaxes for stars as far as 500 light-years, achieving uncertainties below 5% for magnitudes brighter than G=15.[6] These surveys supersede earlier efforts like the Yale Bright Star Catalogue (1982), which listed 9114 stars brighter than magnitude 6.5 but relied on ground-based parallaxes with larger errors. Bright examples in this range highlight the diversity of stellar types and their distribution across constellations. Spica (α Virginis), a binary system of two B-type stars, lies about 254 light-years away and appears as the 15th-brightest star in the night sky at magnitude 0.98; its distance is confirmed by Gaia DR3 parallax measurements. Similarly, Bellatrix (γ Orionis), a B2 III giant in Orion, is positioned at roughly 250 light-years with an apparent magnitude of 1.64, serving as a key calibrator for interstellar dust studies due to its line-of-sight path. Elnath (β Tauri), marking the horn of Taurus, resides at 131 light-years and shines at magnitude 1.65 as a B7 III star, its proximity allowing detailed spectroscopy of its rotating envelope.[6] Further representatives include Alkaid (η Ursae Majoris), the brightest star in the Big Dipper's handle at 104 light-years and magnitude 1.86 (spectral type B3 V), whose rapid rotation was precisely measured by Gaia proper motions; and Alphard (α Hydrae), a K3 III giant in Hydra at 177 light-years with magnitude 1.99, notable for its chromospheric activity observed in ultraviolet spectra.[60] Algieba (γ¹ Leonis), a K0 III giant in Leo forming a visual binary, is located 130 light-years away at magnitude 2.23, exemplifying evolved stars in this volume. These stars are often cataloged by constellation in compilations like the Bright Star Catalogue, which groups them for navigational and astrophysical reference. Observational challenges in this range arise primarily from interstellar extinction, where dust grains absorb and scatter light, reddening spectra and dimming fainter companions by up to 0.5 magnitudes per kiloparsec along certain sightlines. Gaia's multi-band photometry (G, BP, RP) mitigates this by enabling extinction corrections, allowing cleaner lists of intrinsic luminosities for population studies. For instance, subsets of the Gaia DR3 catalog filtered by distance (30-150 parsecs) and brightness yield thousands of entries per constellation, such as over 200 in Orion alone, emphasizing the region's role in tracing spiral arm segments.| Star Name | Constellation | Distance (ly) | Apparent Magnitude | Spectral Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaid (η UMa) | Ursa Major | 104 | 1.86 | B3 V |

| Dubhe (α UMa) | Ursa Major | 123 | 1.81 | A0 V + K0 V |

| Elnath (β Tau) | Taurus | 131 | 1.65 | B7 III |

| Algieba (γ¹ Leo) | Leo | 130 | 2.23 | K0 III |

| Alphard (α Hya) | Hydra | 177 | 1.99 | K3 III |

| Peacock (α Pav) | Pavo | 180 | 1.94 | B3 V |

| Spica (α Vir) | Virgo | 254 | 0.98 | B1 III-IV + B2 V |

| Bellatrix (γ Ori) | Orion | 250 | 1.64 | B2 III |

Stars and Stellar Systems

Stars by Luminosity and Spectral Type

The Morgan-Keenan (MK) system, developed in 1943 by William W. Morgan and Philip C. Keenan, provides a two-dimensional framework for classifying stars based on their spectral characteristics and luminosity. Spectral types are denoted by the letters O, B, A, F, G, K, and M, arranged in order of decreasing surface temperature, from over 30,000 K for O-type stars to below 3,500 K for M-type stars. This sequence reflects the strength and appearance of absorption lines in a star's spectrum, such as the dominance of helium lines in O and B types, hydrogen lines peaking in A types, and molecular bands in cooler K and M types.[61][62] The system builds on the earlier Harvard classification by incorporating luminosity information via Roman numerals appended to the spectral type, enabling astronomers to infer evolutionary stages without direct distance measurements.[63] Luminosity classes in the MK system range from 0 (hypergiants) to VII (white dwarfs), with class V representing main-sequence stars like the Sun (G2V). Classes I through III denote evolved, more luminous stars: Ia-0 for extremely luminous hypergiants, Ia for bright supergiants, Ib for less luminous supergiants, II for bright giants, and III for normal giants. Subgiants (IV) and subdwarfs (VI) bridge the main sequence to evolved phases, while class D (or VII) applies to white dwarfs. This classification correlates with a star's radius and density, as higher luminosity classes indicate larger, more extended atmospheres. For instance, hypergiants like VY Canis Majoris (spectral type M5-Ia) exhibit extreme sizes, with a radius approximately 1,420 times that of the Sun, driven by their late-stage evolution as massive stars.[64] Giants, such as Aldebaran (K5 III), have radii around 44 times solar and luminosities exceeding 400 times that of the Sun, marking them as post-main-sequence objects with expanded envelopes.[65] White dwarfs, like Sirius B (DA2, class D), are compact remnants with radii comparable to Earth's and luminosities far below main-sequence counterparts of similar spectral type.[66] The Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram illustrates these classifications by plotting stellar luminosity (or absolute magnitude) against surface temperature (or spectral type), revealing patterns in stellar evolution. Main-sequence stars form a diagonal band from hot, luminous O types to cool, dim M types; giants and supergiants cluster in an upper branch, while white dwarfs occupy a lower region. This diagram, independently developed by Ejnar Hertzsprung and Henry Norris Russell around 1910, underscores how spectral type and luminosity class together map a star's position on evolutionary tracks, from hydrogen fusion on the main sequence to post-fusion expansion in giants and contraction in white dwarfs.[67] Absolute visual magnitude (M_V), a measure of intrinsic brightness in the V band, varies systematically with spectral type for main-sequence stars, as shown in the table below (values approximate for class V stars).[68]| Spectral Type | Temperature (K) | Absolute Visual Magnitude (M_V) | Luminosity (L_⊙) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O5 | 54,000 | -5.0 | 65,000 |

| B0 | 25,000 | -3.9 | 20,000 |

| A0 | 10,000 | 0.7 | 50 |

| F0 | 7,300 | 2.6 | 6 |

| G0 | 6,000 | 4.4 | 1.3 |

| K0 | 4,900 | 5.9 | 0.46 |

| M0 | 3,800 | 8.8 | 0.08 |

Binary and Multiple Star Systems

Binary and multiple star systems are gravitationally bound configurations where two or more stars orbit a common center of mass, comprising a significant fraction of stellar populations in the Milky Way. These systems provide critical insights into stellar masses, ages, and evolutionary processes through their orbital dynamics, with catalogs such as the Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars documenting over 4,000 visual binary orbits as of 2025 derived from astrometric observations. Approximately half of all stars are found in binary or multiple configurations, enabling precise measurements of stellar parameters that are otherwise challenging for single stars.[72][73][74] Visual binaries are systems where the individual components can be spatially resolved through telescopes, allowing direct measurement of their relative positions and proper motions over time to derive orbital elements. A prominent example is the Sirius system, consisting of Sirius A (a main-sequence A-type star) and Sirius B (a white dwarf), with a semi-major axis of approximately 20 AU and an orbital period of about 50 years. Such wide separations, often exceeding tens of AU, enable long-term monitoring but require extended observation baselines for complete orbits.[75][66] Spectroscopic binaries are identified through periodic Doppler shifts in their spectral lines due to orbital motion, revealing the radial velocity amplitudes without resolving the components spatially. The Algol system (β Persei) exemplifies a spectroscopic binary that is also eclipsing, with an orbital period of 2.867 days and components including a B-type subgiant and a K-type star, where the eclipses provide additional photometric constraints on the orbit. Eclipsing binaries like Algol allow for the determination of absolute stellar radii and inclinations approaching 90 degrees, making them invaluable for calibrating stellar models.[76][77] Multiple star systems extend beyond binaries to include triples, quadruples, and higher multiplicities, often arranged in hierarchical configurations to maintain long-term stability. The Alpha Centauri system is a well-studied triple, featuring the close binary pair Alpha Centauri A and B (spectral types G2V and K1V, respectively) with an orbital period of 79.9 years and semi-major axis of 23.5 AU, orbited distantly by Proxima Centauri (M5.5V) at a separation of about 0.21 light-years and an orbital period exceeding 500,000 years. Castor (α Geminorum) represents a higher-multiplicity example with six components: two tight spectroscopic binaries (Castor A with a 9.2-day period and Castor B with a 2.9-day period) forming a wider visual pair orbiting each other every 467 years, accompanied by two additional faint red dwarfs in a loose outer hierarchy. Orbital periods in multiple systems span from days for close inner pairs to millennia for outer orbits, as cataloged in resources like the Multiple Star Catalog, which organizes over 1,000 hierarchical systems by nested binary structures.[78][79][80] Hierarchical arrangements in multiple systems ensure dynamical stability by treating subsystems as effective two-body problems, where the outer companion's orbit is much wider than the inner binary's, minimizing perturbations. Stability criteria, such as those derived from the three-body problem, require the ratio of the outer to inner semi-major axes to exceed approximately 3–5 for triples, preventing chaotic ejections or close encounters that could destabilize the configuration over gigayears. The three-body problem itself lacks a general closed-form solution, leading to numerical simulations that confirm hierarchical triples like Alpha Centauri remain stable due to their wide separations, with energy dissipation through tidal friction further aiding longevity.[81][82]Variable and Peculiar Stars

Variable and peculiar stars encompass a diverse group of celestial objects whose brightness or spectral characteristics deviate from typical main-sequence stars, often due to intrinsic pulsations, orbital interactions, or unusual chemical compositions. The primary resource for cataloging these stars is the General Catalogue of Variable Stars (GCVS), maintained by the Sternberg Astronomical Institute, which as of November 2025 includes over 89,000 entries for variable stars primarily in the Milky Way, classifying them by type and providing parameters such as periods, amplitudes, and coordinates.[83][84] This catalog serves as the foundational reference for astronomers studying variability, enabling the identification of patterns like the period-luminosity relation in certain subtypes, with recent enhancements from Gaia DR3 providing improved astrometry and photometry for millions of variables.[85] Pulsating variable stars exhibit periodic changes in radius and temperature, leading to brightness variations that are crucial for distance measurements in astronomy. Classical Cepheids, a prominent subtype, follow the period-luminosity relation discovered by Henrietta Swan Leavitt in 1912, where longer pulsation periods correspond to greater intrinsic luminosity, making them standard candles for cosmic distances. Delta Cephei, the prototype of this class with a pulsation period of approximately 5.4 days, exemplifies their behavior, varying from visual magnitude 3.5 to 4.4. Catalogs such as the Galactic Cepheid Database, derived from GCVS data, list thousands of these stars, initially compiling over 500 classical Cepheids with updated positions and photometry from surveys like Gaia.[86] RR Lyrae stars, another pulsating class, have shorter periods of 0.2 to 1.0 days and serve as distance indicators for globular clusters and the galactic halo; the Gaia DR3 catalog identifies over 200,000 RR Lyrae stars across the sky, providing precise light curves and metallicities for population studies.[87] The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) further supplements these lists with dedicated catalogs, such as over 24,000 RR Lyrae in the Large Magellanic Cloud.[88] Eclipsing and cataclysmic variables display variability driven by geometric or explosive phenomena, often in binary systems. Algol-type eclipsing binaries, named after the prototype Algol (Beta Persei), show periodic dips in brightness due to one star occulting the other, with well-defined eclipse timings; the Catalogue of Algol-Type Binary Stars lists 411 such systems, detailing orbital periods typically from 0.5 to 10 days and spectral types.[89] An updated compilation includes nearly 4,680 northern examples with Algol-like light curves, emphasizing their semi-detached configurations where mass transfer occurs.[90] Cataclysmic variables, including novae, undergo sudden brightenings from thermonuclear runaways on white dwarf surfaces; Nova Cygni 1975 (V1500 Cygni) reached a peak magnitude of 1.8, one of the brightest 20th-century novae, with post-eruption observations revealing a 3.2-hour photometric period linked to its binary nature. The GCVS classifies novae under type N, cataloging hundreds in the Milky Way, while broader cataclysmic variable lists from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) track recurrent events and light curves.[91] Peculiar stars feature anomalous spectra due to extreme compositions or evolutionary stages, distinguishing them from standard classifications. Wolf-Rayet stars, characterized by broad emission lines from highly ionized elements like helium, carbon, and nitrogen, indicate strong stellar winds and mass loss; the latest Galactic Wolf-Rayet Catalogue (version 1.33, as of August 2025) enumerates 705 such objects, with subtypes WN (nitrogen-rich) and WC (carbon-rich) dominating in a 1.5:1 ratio.[92] These stars, often obscured by dust, are identified through surveys revealing high ionization states, as in the case of WR 1 (HD 4004) with its WN3 spectral type. Carbon stars, enriched in carbon from dredge-up processes in asymptotic giant branch evolution, display molecular bands of C2 and CN that redden their light and alter spectra; the General Catalog of Galactic Carbon Stars compiles 6,891 entries, focusing on cool giants with infrared excesses.[93] Examples include R Leporis (the "Crimson Star"), a well-known carbon star with a distinct red hue, cataloged for its variability and s-process element enhancements. Variability in these peculiar stars often arises from pulsations or binarity, though detailed binary analyses are covered elsewhere.Stellar Evolution End Products

Supernovae and Their Remnants

Supernovae represent cataclysmic explosions marking the end stages of stellar evolution, releasing immense energy and producing expansive gaseous remnants observable across various wavelengths. These events are broadly classified into Type Ia, arising from the thermonuclear detonation of a carbon-oxygen white dwarf in a binary system that exceeds the Chandrasekhar mass limit, and Type II, resulting from the core-collapse of massive stars with initial masses greater than about 8 solar masses.[94] Type Ia supernovae exhibit remarkably uniform light curves, peaking at an absolute visual magnitude of approximately -19.5 with a scatter of only 0.3 magnitudes, enabling their use as standard candles for measuring cosmic distances after corrections for light-curve width variations.[95] Their spectra show strong silicon absorption lines near maximum light, evolving to iron-dominated features over weeks, reflecting the consistent nickel-56 decay powering the luminosity.[96] In contrast, Type II supernovae display diverse light curves, with Type II-P subtypes featuring a plateau phase lasting 80-100 days at around -16 to -17 magnitudes due to hydrogen envelope recombination, followed by a steep decline, while Type II-L variants show a linear decay without a plateau.[97] Their spectra are hydrogen-rich, with P-Cygni profiles indicating expanding atmospheres at velocities of 3,000-10,000 km/s, and evolving from broad emission lines to narrower nebular features.[97] Historical records provide direct evidence of supernovae within the Milky Way, with the most prominent being SN 1054, observed on July 4, 1054, as a "guest star" visible in daylight for 23 days and at night for nearly two years, recorded by Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, and Native American astronomers.[98] This event, originating from a progenitor star estimated at 9-11 solar masses, produced the Crab Nebula remnant, identified as its ejecta in 1921 through positional correlation with historical accounts.[99] In the modern era, SN 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud, discovered on February 23, 1987, stands as the closest observed supernova in centuries, reaching a peak visual magnitude of 2.9 and classified as a Type II due to its hydrogen envelope.[100] Notably, it was preceded by a burst of neutrinos detected hours earlier by underground observatories like Kamiokande-II and IMB, totaling about 20 events with energies of 7-36 MeV, confirming core-collapse models and marking the first extraterrestrial neutrino detection from a supernova.[101][100] Supernova remnants form as expanding shells of ionized gas and dust from the ejected material, interacting with the interstellar medium and radiating via synchrotron emission, thermal bremsstrahlung, and line emission. The Crab Nebula, at a distance of 6,500 light-years, spans about 11 light-years and expands at an average velocity of approximately 1,500 km/s, driven by the initial explosion energy of around 10^51 ergs.[102][103] Cassiopeia A, the youngest known Galactic remnant, is estimated to be about 325-350 years old based on proper motion measurements of its ejecta knots, with an expansion velocity averaging around 1,000 km/s for the main shell, though outer knots reach up to 5,000 km/s, indicating an asymmetric explosion from a progenitor red supergiant.[104][105] These remnants, like the Crab's filamentary structure and Cassiopeia A's bright radio and X-ray shells, offer insights into supernova dynamics and nucleosynthesis, with expansion rates decelerating over time due to swept-up mass.[104]Neutron Stars and Pulsars

Neutron stars represent one of the densest forms of matter in the universe, formed from the gravitational collapse of massive stars' cores following core-collapse supernovae. These compact objects, typically with masses around 1.4 solar masses but radii of only about 10-15 kilometers, exhibit extreme physical properties including strong gravitational fields and rapid rotation. Pulsars, a subclass of neutron stars, are characterized by their rapid rotation and strong magnetic fields, which accelerate charged particles to produce beamed electromagnetic radiation detectable as periodic pulses when aligned with Earth's line of sight. The ATNF Pulsar Catalogue serves as the comprehensive database for known pulsars, compiling data on over 4,000 objects including rotation periods, spin-down rates, magnetic field strengths, and binary companions, derived from radio, X-ray, and gamma-ray observations (as of 2025).[106] Among young pulsars, the Crab Pulsar (PSR B0531+21) stands out with its rotation period of 33 milliseconds, making it one of the fastest-spinning examples associated with a historical supernova remnant.[107] Millisecond pulsars, which rotate hundreds of times per second, likely spun up through accretion in binary systems; the prototype is PSR B1937+21, discovered in 1982 with a period of 1.5578 milliseconds, representing the first identified member of this class. Magnetars, a rare subtype of neutron stars with magnetic fields exceeding 10^14 gauss, are cataloged within the ATNF database as anomalous X-ray pulsars (AXPs) and soft gamma repeaters (SGRs); SGR 1806-20 is notable for its giant flare on December 27, 2004, releasing energy equivalent to about 2 × 10^46 ergs isotropically and temporarily disrupting Earth's ionosphere.[108] Isolated neutron stars, which lack binary companions and often do not emit detectable radio pulses, are primarily identified through X-ray surveys; the "Magnificent Seven" refers to a group of seven nearby, thermally emitting examples discovered by the ROSAT All-Sky Survey, with effective temperatures around 10^6 Kelvin and ages of 10^5 to 10^6 years.[109] Binary pulsars provide critical tests of general relativity; the Hulse-Taylor binary (PSR B1913+16), discovered in 1974, consists of two neutron stars in a 7.75-hour orbit with high eccentricity, and its observed orbital decay rate matches predictions from gravitational wave emission to within 0.2%, earning Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics.White Dwarfs

White dwarfs represent the final evolutionary stage for low- to intermediate-mass stars, after they have exhausted their nuclear fuel and shed their outer envelopes. Comprehensive catalogs of these compact objects facilitate studies of stellar evolution, galactic structure, and cosmology. The Montreal White Dwarf Database (MWDD) compiles data on over 70,000 spectroscopically confirmed white dwarfs, including parameters such as effective temperature, surface gravity, and atmospheric composition, drawn from surveys like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and Gaia (as of 2024).[110] Similarly, the Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3) white dwarf catalog identifies approximately 12,700 candidates within 100 parsecs, selected via color-magnitude criteria and low-resolution spectra, enabling precise astrometry and photometry for population analyses.[111] The SDSS Data Release 7 (DR7) white dwarf catalog lists about 20,000 spectroscopically identified examples, emphasizing hydrogen- and helium-dominated atmospheres.[112] These resources track white dwarfs across diverse environments, from isolated field stars to binaries, supporting investigations into their cooling and binary interactions. White dwarfs are classified primarily by their atmospheric spectral features, with the most common types being DA (hydrogen-dominated atmospheres showing Balmer absorption lines) and DB (helium-dominated atmospheres exhibiting neutral helium lines).[113] DA white dwarfs constitute about 80% of the known population, while DB types account for roughly 20%, often appearing in the "DB gap" temperature range of 30,000–45,000 K where hydrogen diffusion may suppress DA signatures.[111] Effective temperatures span from over 100,000 K for newly formed hot white dwarfs to below 4,000 K for cooler ones, reflecting their post-main-sequence age and cooling history.[113] These classifications, refined through high-resolution spectroscopy in catalogs like MWDD, reveal atmospheric evolution driven by gravitational settling and convective mixing. Prominent examples include Sirius B, the first white dwarf discovered, predicted in 1844 by Friedrich Bessel through astrometric perturbations in Sirius A's proper motion and directly observed in 1862.[114] With a mass of approximately 1.02 M⊙ and a radius comparable to Earth's (about 0.0084 R⊙), Sirius B exemplifies the high density of these remnants, packing solar mass into planetary dimensions.[115][66] Another well-studied case is Procyon B, a companion to the F-type star Procyon A, with a mass of about 0.6 M⊙, radius of roughly 0.012 R⊙, and effective temperature around 7,740 K, classifying it as a DQZ white dwarf with carbon and metal features.[116] These binaries, cataloged in resources like the McCook-Sion compilation, provide benchmarks for mass-radius relations and evolutionary models.[117] White dwarfs cool passively through gravothermal contraction and neutrino/photon emission, following well-defined sequences that span billions of years. Initial cooling from progenitor envelopes occurs rapidly, but as luminosity drops below 10^{-2} L⊙, the process slows, with timescales exceeding 10 billion years for masses around 0.6 M⊙ to reach temperatures below 5,000 K.[118] Theoretical models predict that complete cooling to black dwarfs—hypothetical cold, dark remnants with negligible emission—requires over 10^{12} years for typical masses, far exceeding the universe's current age of 13.8 billion years, making observable black dwarfs absent today.[119] These long timescales, validated against cluster luminosity functions, position white dwarfs as cosmic clocks for dating stellar populations.[120] In binary systems, white dwarfs serve as progenitors for classical novae when they accrete hydrogen-rich material from low-mass companions, triggering thermonuclear runaways on their surfaces.[121] Such events, observed in catalogs of cataclysmic variables like those from SDSS, eject shells at speeds up to 3,000 km/s, with recurrence possible over decades to millennia depending on accretion rates below 10^{-8} M⊙ yr^{-1}.[112] Carbon-oxygen white dwarfs are primary hosts, though oxygen-neon types contribute in about one-third of cases, enriching the interstellar medium with processed elements.[122]Extrasolar Planets and Companions

Confirmed Exoplanets

Confirmed exoplanets represent planets outside our solar system that have been verified through rigorous observational confirmation, primarily cataloged in the NASA Exoplanet Archive. As of November 2025, over 6,000 such planets are known, detected via methods that measure stellar effects or direct light from the planets themselves.[123] These detections provide insights into planetary diversity, from rocky worlds to gas giants, and are categorized by the primary detection technique, with host star distances influencing observability and follow-up studies. The transit method identifies exoplanets by observing periodic dips in a star's brightness as a planet passes in front of it, allowing measurements of planetary radii and orbital periods. A notable example is Kepler-452b, an Earth-like super-Earth with a radius about 1.6 times that of Earth, orbiting within the habitable zone of its Sun-like G-type host star every 385 days; the system lies approximately 1,400 light-years away.[124] Another prominent system detected by transits is TRAPPIST-1, located just 40 light-years from Earth, featuring seven rocky, Earth-sized planets orbiting an ultra-cool red dwarf star, with three in the habitable zone and orbital periods ranging from 1.5 to 12 days.[125] The radial velocity method detects exoplanets by measuring the gravitational tug they exert on their host star, causing periodic shifts in the star's spectral lines; this technique excels at determining planetary masses, often expressed in Jupiter masses (M_Jup). The first confirmed exoplanet, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered in 1995 using this method on a Sun-like star 50 light-years away, revealing a hot Jupiter with a mass of 0.46 M_Jup and an orbital period of just 4.2 days, challenging prior theories of planetary formation.[126][127] Direct imaging captures actual photographs of exoplanets by blocking a star's overwhelming light, typically feasible for young, self-luminous gas giants at wide orbits. The HR 8799 system, a young stellar remnant about 30 million years old and 130 light-years distant, hosts four such super-Jupiter planets—b, c, d, and e—imaged in 2008 and later confirmed with orbital motion; their projected semi-major axes are approximately 68 AU for b, 38 AU for c, 24 AU for d, and 16 AU for e, with masses ranging from 5 to 13 M_Jup.[128][129]Exomoons and Protoplanetary Disks

Exomoons, natural satellites orbiting planets outside our solar system, remain elusive despite extensive searches, with only a few candidates identified through indirect methods like transit timing variations (TTVs) and transit depth anomalies caused by tidal interactions between the planet and its moon.[130] The leading candidate is Kepler-1625b-i, announced in 2018, which orbits the gas giant exoplanet Kepler-1625b and is estimated to have a radius of about 4 Earth radii, or roughly 0.35 times that of its host planet (which has a radius of ~11 Earth radii), comparable to Neptune's size. Another candidate is Kepler-1708b-i, proposed in 2022, though neither has been confirmed as of 2025.[130][131] Observations from the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a 4-hour early transit and a 22% deeper transit light curve for Kepler-1625b, interpreted as evidence of the moon's gravitational tug inducing TTVs and the combined silhouetting of planet and moon during transit.[130] These tidal effects highlight how exomoons could perturb their host planets' orbits detectably, though confirmation requires further observations to rule out alternative explanations like additional planets.[132] Protoplanetary disks, flattened structures of gas and dust encircling young stars, serve as the birthplaces of planets and are key to understanding early solar system dynamics.[133] The iconic 2014 Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) image of the disk around HL Tauri, a T Tauri star about 1 million years old and 450 light-years away, revealed multiple concentric rings and gaps extending out to about 90 AU from the star, interpreted as signs of forming protoplanets carving out material through gravitational interactions.[133] These substructures, resolved at 0.04-arcsecond scales, provide direct evidence of the planet formation process in action, with dust grain growth and pebble accretion models explaining the ring patterns.[133] Similarly, the debris disk around Beta Pictoris, a 20-million-year-old A-type star 63 light-years distant, features an inclined, edge-on structure of dust and planetesimals imaged since the 1980s, with inner clearing attributed to a confirmed giant planet sculpting the disk through resonant torques.[134] Circumplanetary disks, smaller disks of material orbiting gas giant planets within protoplanetary systems, are theorized as the primary formation sites for exomoons via processes analogous to our solar system's satellites.[135] In the gas-starved disk model, a subdisk forms from the planet's Hill sphere material during migration, with limited gas supply leading to rapid moon accretion from solids before the disk dissipates viscously.[135] This model, supported by simulations of Jupiter's formation, predicts moons forming via core accretion or capture, with tidal interactions stabilizing orbits over gigayears.[136] The first potential detection of such a disk occurred in 2021 around the exoplanet PDS 70 c using ALMA, revealing a compact dust structure with mass sufficient to form multiple Earth-sized moons.[137]Brown Dwarfs and Free-Floating Planets

Brown dwarfs are substellar objects intermediate in mass between planets and hydrogen-fusing stars, typically spanning 13 to 80 Jupiter masses (M_Jup), where they can sustain deuterium fusion but not hydrogen fusion. This deuterium-burning minimum mass (DBMM) of approximately 13 M_Jup serves as the conventional lower boundary for brown dwarfs, as determined by detailed evolutionary models accounting for initial conditions and atmospheric opacities.[138] The International Astronomical Union (IAU) adopted a working definition in 2003 that emphasizes this fusion capability, distinguishing brown dwarfs from planetary-mass objects while excluding low-mass stars. These objects form via mechanisms similar to stars, such as gravitational collapse of molecular cloud fragments, but cool rapidly after formation due to insufficient mass for prolonged nuclear energy generation. Spectral classification for brown dwarfs extends the stellar sequence beyond M types to L, T, and Y, reflecting progressively cooler effective temperatures and atmospheric compositions dominated by metal hydrides, methane, and ammonia. L-type brown dwarfs, with temperatures of 1300–2400 K, show strong metal hydride absorption and red optical colors, bridging late M dwarfs and cooler objects. T types, cooler at 700–1300 K, exhibit prominent methane (CH₄) absorption in the near-infrared, marking a shift to Jupiter-like atmospheres. The coldest Y types, below 700 K, display ammonia features and even water ice clouds, representing the lowest-mass end of the substellar spectrum.[139] A landmark discovery illustrating these properties is Gliese 229B, identified in 1995 as the companion to the nearby M dwarf Gliese 229A through high-resolution imaging. Its spectrum revealed deep methane absorption bands, confirming it as the first T dwarf with an effective temperature around 950 K and a mass estimated at 20–50 M_Jup.[140] Free-floating planetary-mass objects, often termed free-floating planets or sub-brown dwarfs, have masses below the 13 M_Jup DBMM and lack stellar companionship, making them challenging to distinguish from ejected giant planets observationally. These objects are detected primarily via their faint near- and mid-infrared emissions in deep surveys of star-forming regions and the galactic field, with masses down to a few M_Jup. A prominent example is OTS 44, a young isolated object in the Chamaeleon II molecular cloud with an estimated mass of about 12 M_Jup and an age of 3–5 million years, placing it near or below the planetary-mass boundary (13 M_Jup DBMM). Observations reveal OTS 44 possesses a substantial protoplanetary disk of at least 10 Earth masses, indicating it may form its own satellite system despite its low mass. The Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), conducted from 1997 to 2001, revolutionized the census of brown dwarfs and free-floaters by covering the entire sky in the near-infrared, revealing over 100 L and T dwarfs in its initial years, many isolated. This survey identified key free-floating candidates through proper motion and color selections, contributing to estimates that such objects may constitute 5–10% of substellar populations in young clusters. Later all-sky missions like WISE built on 2MASS to extend detections to Y dwarfs and lower-mass free-floaters, enhancing understanding of the substellar initial mass function.[139]Nebulae and Interstellar Matter

Emission and Reflection Nebulae

Emission and reflection nebulae are interstellar clouds illuminated by the light of nearby stars, appearing bright against the cosmic backdrop without significant internal heating from ongoing star formation in the same manner as other nebula types. Emission nebulae, specifically H II regions, consist of ionized hydrogen gas that glows due to ultraviolet radiation from hot O and B-type stars, which strips electrons from hydrogen atoms; as these electrons recombine with protons, they emit photons primarily through spectral lines such as H-alpha at 656.3 nm, the prominent red Balmer line resulting from the n=3 to n=2 transition.[141][142] Reflection nebulae, in contrast, do not involve ionization but instead scatter starlight off dust grains, often displaying a bluish hue because smaller dust particles preferentially scatter shorter blue wavelengths via Rayleigh scattering, similar to the mechanism that colors Earth's sky.[143] The Orion Nebula (M42) exemplifies an emission nebula as a vast H II region approximately 1,350 light-years from Earth, spanning about 24 light-years and containing over 700 young stars.[144] Its ionization stems from the ultraviolet output of the Trapezium cluster, a tight grouping of four massive O-type stars at its core, which heat and excite the surrounding gas to produce the nebula's characteristic red H-alpha glow alongside green oxygen and red sulfur emissions observed in Hubble imagery.[144] Another notable feature is the illuminated edge of the Horsehead Nebula (Barnard 33), a dark nebula silhouette within the larger emission complex IC 434 in Orion, where the glowing boundary arises from H II ionization by nearby massive stars, captured prominently in H-alpha filters at a distance of about 1,400 light-years.[145] Reflection nebulae highlight dust's role in redistributing stellar light without altering its spectrum significantly. The Pleiades cluster (M45), located roughly 440 light-years away, is enveloped in such a nebula where fine interstellar dust scatters the blue light from its young B-type stars, creating a hazy veil visible in long-exposure images and extending several degrees across the sky.[146] Similarly, the Witch Head Nebula (IC 2118) in Eridanus, about 900 light-years distant and spanning 50 light-years, reflects the intense blue light of the nearby supergiant Rigel (Beta Orionis), with its ethereal, head-shaped form resulting from efficient blue scattering by dust grains rather than intrinsic emission.[147]Planetary and Protoplanetary Nebulae

Planetary nebulae represent ionized gaseous shells ejected by low- to intermediate-mass stars (0.8–8 solar masses) in the final stages of their evolution, following the asymptotic giant branch phase, and are illuminated by their hot central white dwarf stars. These structures typically span 0.1 to 1 light-year in diameter and exhibit diverse morphologies shaped by the interaction between the stellar wind and the surrounding interstellar medium. Databases such as the Hong Kong/AAO/Strasbourg Hα (HASH) planetary nebula database list approximately 2,700 confirmed galactic planetary nebulae as of 2023, providing coordinates, sizes, and central star identifications for systematic study.[148] Morphologies range from spherical or ellipsoidal shells, indicative of symmetric ejections, to bipolar or multipolar forms influenced by binary companions or magnetic fields, with about 20% classified as asymmetric in surveys of the Galactic bulge. Central stars, often O- or B-type with temperatures exceeding 50,000 K, have visual magnitudes typically between 12 and 18, reflecting their faintness due to high temperatures and small radii. Notable examples include the Ring Nebula (M57, NGC 6720) in Lyra, located approximately 2,500 light-years away, which displays a classic ring-like morphology with an inner toroidal structure and outer halo, spanning about 1 light-year across. Its central white dwarf has a visual magnitude of 15.3 and effective temperature around 120,000 K. Another prominent planetary nebula is the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) in Aquarius, situated 650 light-years distant and resembling an eye-like structure due to its asymmetric inner shell and cometary knots, with a diameter of nearly 3 light-years. The central star of the Helix is a magnitude 13.5 white dwarf, potentially accreting material that influences the nebula's dynamics. Protoplanetary nebulae mark the brief transitional phase (roughly 1,000–10,000 years) between the asymptotic giant branch and full planetary nebula stages, characterized by dusty, often bipolar outflows from post-asymptotic giant branch stars still enshrouded in circumstellar material. These objects are rarer, with catalogs identifying fewer than 100 confirmed examples based on infrared excesses and molecular line emissions. Expansion ages are derived from kinematic measurements, typically around 10,000 years, reflecting the onset of ionization. Shell morphologies in protoplanetary nebulae frequently show bipolar lobes with equatorial disks, driven by binary interactions or rapid rotation. A key example is the Red Rectangle Nebula (HD 44179) in Monoceros, about 2,300 light-years away, featuring a distinctive bipolar structure with ladder-like rungs of gas and dust, indicative of periodic ejections from a binary post-asymptotic giant branch system. Its dynamical expansion age is estimated at 14,000 years, with the central binary's primary star at visual magnitude 9.1 and temperature near 8,000 K. These nebulae provide insights into the mechanisms shaping the more evolved planetary forms, with central stars evolving toward white dwarf cores as detailed in studies of stellar remnants.Dark Nebulae and Molecular Clouds

Dark nebulae are dense clouds of interstellar dust and gas that obscure the light from background stars, appearing as dark silhouettes against brighter regions of the sky. These structures are typically cold, with temperatures around 10-20 K, and play a crucial role in shielding molecular material from ionizing radiation, allowing complex chemistry to occur within them. A prominent example is the Horsehead Nebula (Barnard 33), a pillar-shaped dark cloud approximately 5 light-years across and located about 1,400 light-years away in the constellation Orion, where it is silhouetted against the glowing emission nebula IC 434. Recent James Webb Space Telescope observations in 2024 have provided unprecedented infrared views of its structure, highlighting the interplay between ionising radiation and dust.[149][145][150] Another well-known dark nebula is the Coalsack, a large, irregular patch in the constellation Crux visible to the naked eye from the Southern Hemisphere, spanning about 7 degrees across and situated roughly 600 light-years distant; it dims the light of background stars by 1 to 1.5 magnitudes due to its high dust content.[151][152] Molecular clouds represent the densest phases of the interstellar medium, consisting primarily of molecular hydrogen (H₂) along with other molecules, dust, and trace amounts of metals, often extending over tens to hundreds of light-years and containing masses from thousands to millions of solar masses. These clouds serve as the primary sites of star formation, where gravitational collapse leads to the birth of protostars within dense cores. The Taurus Molecular Cloud, located approximately 450 light-years away, is a nearby example spanning about 50 light-years and actively forming low-mass stars, including T Tauri-type objects, through the fragmentation of its filaments.[153] In contrast, the Orion A Molecular Cloud, part of the larger Orion complex about 1,350 light-years distant, is a giant structure with an estimated mass of around 10,000 solar masses, featuring intense star-forming activity driven by its high density and turbulent motions.[154] Mapping molecular clouds often relies on observations of carbon monoxide (CO) emission lines, particularly the J=1-0 transition at 115 GHz, which traces the distribution of H₂ since CO is abundant and emits efficiently at the low temperatures of these clouds (10-20 K). CO surveys, such as those conducted with radio telescopes like the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) or the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), reveal the cloud's velocity structure, density variations, and total mass via the CO-to-H₂ conversion factor (X_CO ≈ 2 × 10²⁰ cm⁻² K⁻¹ km⁻¹ s). These maps indicate that star formation rates in molecular clouds are inefficient, with only about 1% of the cloud's mass converting to stars per free-fall time (typically 1-2 million years), as regulated by magnetic fields, turbulence, and feedback from young stars.[155][156]Star Clusters

Open Clusters

Open clusters are young, loosely bound groups of stars formed within the galactic disk of the Milky Way, typically comprising 100 to 1,000 stars that originated from the same giant molecular cloud and share similar ages and compositions.[157] Unlike denser structures, these clusters have lower stellar densities and are susceptible to disruption by the galaxy's tidal forces and gravitational interactions.[158] Many remain partially embedded in reflective or emission nebulae from their formation environments, providing insights into early stellar evolution.[159] Prominent examples include the Pleiades (M45), a well-known open cluster approximately 100 million years old and situated about 444 light-years from Earth in the constellation Taurus.[160] Another notable cluster is the Hyades, the nearest to our solar system at around 150 light-years away, which forms part of a larger moving group of stars sharing common proper motion.[161] The Jewel Box (NGC 4755), centered on the star Kappa Crucis in the southern constellation Crux, exemplifies a colorful young open cluster with 100 to 1,000 member stars, including massive blue supergiants and a distinctive red supergiant.[162] Due to their loose binding, open clusters typically dissolve on timescales of about 100 million years, primarily through gravitational encounters with passing stars, molecular clouds, or the Milky Way's tidal field, which gradually strip away members and unbind the system.[163] This short lifespan means only a fraction of formed clusters survive long enough to contribute significantly to the field star population in the galactic disk.[164]Globular Clusters