Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

2012 VP113

View on Wikipedia

2012 VP113 imaged by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope on 9 October 2021 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | |

| Discovery site | Cerro Tololo Obs. |

| Discovery date | 5 November 2012 |

| Designations | |

| 2012 VP113 | |

| Biden (nickname) | |

| Orbital characteristics (barycentric)[4] | |

| Epoch 5 May 2025 (JD 2460800.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 3[2] | |

| Observation arc | 16.94 yr (6,187 d) |

| Earliest precovery date | 19 September 2007 |

| Aphelion | 444.1 AU |

| Perihelion | 80.52 AU |

| 262.3 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.6931 |

| 4,246 yr[4] | |

| 24.05° | |

| 0° 0m 0.836s / day | |

| Inclination | 24.0563°±0.006° |

| 90.80° | |

| ≈ September 1979[5] | |

| 293.90° | |

| Known satellites | 0 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 450 km (calc. for albedo 0.15)[6] | |

| |

| 23.5[7] | |

| 4.05[2] | |

2012 VP113 is a trans-Neptunian object (TNO) orbiting the Sun on an extremely wide elliptical orbit. It is classified as a sednoid because its orbit never comes closer than 80.5 AU (12.04 billion km; 7.48 billion mi) from the Sun, which is far enough away from the giant planets that their gravitational influence cannot affect the object's orbit noticeably. It was discovered on 5 November 2012 at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, by American astronomers Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo, who nicknamed the object "Biden" because of its "VP" abbreviation.[8] The discovery was announced on 26 March 2014.[6][8] The object's size has not been measured, but its brightness suggests it is around 450 km (280 mi) in diameter.[6][9] 2012 VP113 has a reddish color similar to many other TNOs.[6]

2012 VP113 has not yet been imaged by high-resolution telescopes, so it has no known moons.[10] The Hubble Space Telescope is planned to image 2012 VP113 in 2026, which should determine if it has significantly sized moons.[10]

History

[edit]Discovery

[edit]2012 VP113 was first reported to have been observed on 5 November 2012[1] with NOAO's 4-meter Víctor M. Blanco Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory.[11] Carnegie's 6.5-meter Magellan telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile was used to determine its orbit and surface properties.[11]

Before being announced to the public, 2012 VP113 was only tracked by Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (807) and Las Campanas Observatory (304).[12]

2012 VP113 had previously been observed (but not reported) as early as September 2007.[12]

Nickname

[edit]2012 VP113 was abbreviated "VP" and nicknamed "Biden" by the discovery team, after Joe Biden who was then the vice president ("VP") of the United States in 2012.[8]

Physical characteristics

[edit]It has an absolute magnitude of 4.0,[12] which means it may be large enough to be a dwarf planet.[13] The diameter and geometric albedo of 2012 VP113 has not been measured.[6][9] If 2012 VP113 has a moderate geometric albedo of 15% (typical of TNOs), its diameter would be around 450 km (280 mi).[6] A wider range of albedos gives a possible diameter range of 300–1,000 km (190–620 mi).[9] It is expected to be about half the size of Sedna and similar in size to Huya.[9] Its surface is moderately red in color, resulting from chemical changes produced by the effect of radiation on frozen water, methane, and carbon dioxide.[14] This optical color is consistent with formation in the gas-giant region and not the classical Kuiper belt, which is dominated by ultra-red colored objects.[6]

Orbit and classification

[edit]

2012 VP113 has the farthest perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) of all known minor planets and all known objects in the Solar System as of 2025[update], greater than Sedna's.[15] Though its perihelion is farther, 2012 VP113 has an aphelion only about half of Sedna's. It is the second discovered sednoid, with a semi-major axis beyond 150 AU and a perihelion greater than 50 AU. The similarity of the orbit of 2012 VP113 to other known extreme trans-Neptunian objects led Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo to suggest that an undiscovered object, Planet Nine, in the outer Solar System is shepherding these distant objects into similar type orbits.[6].

Its last perihelion was within a couple months of September 1979.[5] The paucity of bodies with perihelia at 50–75 AU appears not to be an observational artifact.[6]

It is possibly a member of a hypothesized Hills cloud.[9][11][16] It has a perihelion, argument of perihelion, and current position in the sky similar to those of Sedna.[9] In fact, all known Solar System bodies with semi-major axes over 150 AU and perihelia greater than Neptune's have arguments of perihelion clustered near 340°±55°.[6] This could indicate a similar formation mechanism for these bodies.[6] (148209) 2000 CR105 was the first such object discovered.

It is currently unknown how 2012 VP113 acquired a perihelion distance beyond the Kuiper belt. The characteristics of its orbit, like those of Sedna's, have been explained as possibly created by a passing star or a trans-Neptunian planet of several Earth masses hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun.[17] The orbital architecture of the trans-Plutonian region may signal the presence of more than one planet.[18][19] 2012 VP113 could even be captured from another planetary system.[13] However, it is considered more likely that the perihelion of 2012 VP113 was raised by multiple interactions within the crowded confines of the open star cluster in which the Sun formed.[9]

-

Simulated view showing the orbit of 2012 VP113

-

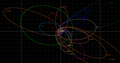

2012 VP113 orbit in white with hypothetical Planet Nine

-

The orbits of known distant objects with large aphelion distances over 200 AU

See also

[edit]- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun

- 90377 Sedna – first sednoid discovered

- 541132 Leleākūhonua – third sednoid discovered

- List of hyperbolic comets

- List of possible dwarf planets

- Other large aphelion objects

- (668643) 2012 DR30 (15–2880 AU)

- 2005 VX3 (4–1630 AU)

- (709487) 2013 BL76 (8–1870 AU)

- 2014 FE72 (36–2680 AU)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "MPEC 2014-F40 : 2012 VP113". IAU Minor Planet Center. 26 March 2014. (K12VB3P)

- ^ a b c "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2012 VP113)" (3 December 2021 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Wm. Robert (7 October 2018). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b "JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris for (2012 VP113) at epoch JD 2460800.5". JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 15 July 2025. Solution using the Solar System Barycenter. Ephemeris Type: Elements and Center: @0)

- ^ a b "Horizons Batch for 2012 VP113 on 1979-Sep-28" (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). JPL Horizons. Retrieved 21 June 2022. (JPL#9, Soln.date: 3 December 2021)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (March 2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–474. arXiv:2310.20614. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ad2686. PMID 24670765. S2CID 4393431. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^ "2012 VP113 – Summary". AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Witze, Alexandra (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet stretches Solar System's edge". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14921. S2CID 124305879.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lakdawalla, Emily (26 March 2014). "A second Sedna! What does it mean?". Planetary Society blogs. The Planetary Society.

- ^ a b Proudfoot, Benjamin (August 2025). "A Search For The Moons of Mid-Sized TNOs". Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes. Space Telescope Science Institute: HST Proposal 18010. Bibcode:2025hst..prop18010P. Cycle 33. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b c "NASA Supported Research Helps Redefine Solar System's Edge". NASA. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b c "2012 VP113". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b Sheppard, Scott S. "Beyond the Edge of the Solar System: The Inner Oort Cloud Population". Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Sample, Ian (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet discovery hints at a hidden Super Earth in solar system". The Guardian.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (26 March 2014). "A New Planetoid Reported in Far Reaches of Solar System". The New York Times.

- ^ Wall, Mike (26 March 2014). "New Dwarf Planet Found at Solar System's Edge, Hints at Possible Faraway 'Planet X'". Space.com web site. TechMediaNetwork. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "A new object at the edge of our Solar System discovered". Physorg.com. 26 March 2014.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (1 September 2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, S. J. (11 January 2015). "Flipping minor bodies: what comet 96P/Machholz 1 can tell us about the orbital evolution of extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the production of near-Earth objects on retrograde orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 446 (2): 1867–1873. arXiv:1410.6307. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.446.1867D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2230.

External links

[edit]- 2012 VP113 Inner Oort Cloud Object Discovery Images from Scott S. Sheppard/Carnegie Institution for Science.

- 2012 VP113 has Q=460 ± 30 Archived 28 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (mpml: CFHT 2011-Oct-22 precovery)

- List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects, Johnston's Archive

- List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects, Minor Planet Center

- 2012 VP113 at the JPL Small-Body Database

2012 VP113

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and Naming

Discovery Circumstances

2012 VP113 was discovered on November 5, 2012, by astronomers Scott S. Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science and Chad A. Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory, during observations at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.[1][5] The detection utilized the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) mounted on the Victor M. Blanco 4 m Telescope, which provided the wide-field imaging capability necessary for spotting faint, slow-moving objects in the distant outer Solar System.[1][6] This discovery formed part of a dedicated survey for trans-Neptunian objects with perihelia exceeding 30 AU, particularly targeting regions beyond 50 AU where such bodies are expected to exhibit minimal motion between exposures.[1] The strategy involved systematic imaging of large sky areas to identify candidates with unusual orbital characteristics, building on prior searches that had revealed Sedna in 2003.[1][7] Precovery identifications extended the known observational history of 2012 VP113, with the object recognized in archival images from as early as September 19, 2007, thereby lengthening the observation arc to over 16 years and refining initial orbital estimates.[8] The object's existence was formally announced on March 26, 2014, through a publication in Nature by Trujillo and Sheppard, which emphasized its highly eccentric orbit with a perihelion of approximately 80 AU.[1]Informal Nickname

The informal nickname "Biden" for 2012 VP113 was coined by its discoverers, astronomers Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo, in reference to the "VP" in the object's provisional designation, which evokes "Vice President" and alludes to Joe Biden, who was the U.S. Vice President at the time of the discovery in 2012.[9][10] Since its announcement in 2014, the nickname "Biden" has been used informally in scientific literature, media reports, and popular discussions to refer to the object, providing a memorable shorthand for this distant trans-Neptunian body.[11][12] However, it has not been officially adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), and the object retains its provisional designation of 2012 VP113 without a permanent number or name.[13] This playful naming aligns with a tradition in astronomy of assigning informal monikers to remote Solar System objects, such as the earlier "Sedna" for another distant body that later received official naming, though 2012 VP113's extreme distance and faintness have delayed any formal naming process under IAU guidelines.[9][11]Physical Characteristics

Size and Albedo

The diameter of 2012 VP113 has not been directly measured but is estimated from its absolute magnitude and assumed geometric albedo using the standard relation for trans-Neptunian objects:km, where is the diameter, is the geometric albedo, and is the absolute magnitude in the V-band (assumed equivalent for R-band photometry here).[14] With and a moderate albedo of typical for trans-Neptunian objects, the estimated diameter is approximately 450 km.[1] This assumption derives from the object's observed reduced magnitude of 3.8 ± 0.04 in the R-band at a heliocentric distance of 83 AU, converted via standard photometric relations.[1] Varying the albedo over a plausible range for such objects (0.04 to 0.4) yields a diameter range of 300–1,000 km, reflecting uncertainties in surface reflectivity.[1] For comparison, this makes 2012 VP113 roughly half the size of Sedna, which has an estimated diameter of 1,000 km under similar albedo assumptions.[1] At the upper end of the size range, 2012 VP113 could approach dwarf planet candidacy, though its current estimate places it below the typical ~600 km threshold for hydrostatic equilibrium in icy bodies.[1] No direct mass measurement exists for 2012 VP113, but assuming a spherical shape and low density similar to other trans-Neptunian objects (~1–2 g/cm³, consistent with icy compositions and measured densities of comparably sized bodies like those in the 300–600 km range), the implied mass would be on the order of kg.[15] To refine the size estimate and potentially resolve its shape or detect moons, imaging with the Hubble Space Telescope has been scheduled under proposal 18010 in Cycle 33 (2026), targeting mid-sized trans-Neptunian objects for high-resolution observations.[16]

Surface Properties

2012 VP113 displays a moderately red coloration in the visible spectrum, characteristic of many trans-Neptunian objects, with measured color indices of B-V = 0.88 ± 0.08 and V-R = 0.55 ± 0.07 based on broadband photometry from multiple epochs.[17] This reddish hue arises from the processing of surface materials by solar and cosmic radiation over billions of years.[1] The object's reflectivity spectrum is featureless across the 0.4–0.9 μm range, exhibiting a linear red spectral slope of 13 ± 2% per 100 nm, which aligns with observations of other detached disk objects.[1] Such a slope indicates an organic-rich surface dominated by irradiated hydrocarbons, likely in the form of tholins—complex, reddish polymers produced from the irradiation of simple ices.[1] Water ice is also inferred as a primary component, contributing to the overall albedo and spectral neutrality in certain bands, while more volatile species like methane are absent, consistent with the object's extreme heliocentric distance preventing their retention.[1] No moons or companions have been detected for 2012 VP113 despite targeted searches in the original discovery images from the Dark Energy Camera and follow-up observations with the Magellan and Subaru telescopes, which would have revealed any significant perturbers within the surveyed fields.[1] The lack of observed orbital perturbations further constrains potential companions to masses below those capable of inducing measurable effects over the observation baseline.[1] Photometric monitoring reveals minimal brightness variations, with a lightcurve amplitude upper limit of less than 0.15 magnitudes derived from multi-night observations, implying a nearly spherical shape with no prominent surface features or elongations.[1] This homogeneity supports the interpretation of a geologically inactive surface shaped primarily by primordial accretion and long-term irradiation.[1]Orbital Parameters

Key Elements

2012 VP113 orbits the Sun on a highly elongated path characterized by a semi-major axis of 273.1 AU (epoch 2024-Oct-17), which represents the average distance from the Sun over the course of its orbit.[18][2] This places the object far beyond the Kuiper Belt, in the inner Oort Cloud region. The semi-major axis is a fundamental parameter derived from observations and used to compute other orbital elements via Keplerian mechanics. The object's perihelion distance, the closest approach to the Sun, is 80.60 AU, marking the farthest known perihelion for any minor planet as of 2025.[18][2] Its aphelion, the farthest point from the Sun, reaches 466 AU. These extreme distances highlight the orbit's vast scale, with 2012 VP113 spending most of its time near aphelion in the distant outer solar system. The eccentricity of 0.705 quantifies this elongation, indicating a highly elliptical trajectory where the object swings dramatically between perihelion and aphelion.[18][2] The orbital period of 2012 VP113 is 4,514 Earth years, determined using Kepler's third law, which states that the square of the orbital period (in years) is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis (in AU): . For objects orbiting the Sun, the constant of proportionality is 1, so . Substituting AU yields , and years, confirming the lengthy duration of one complete orbit.[18][2] Additional angular elements define the orbit's orientation relative to the ecliptic plane: an inclination of 24.0°, an argument of perihelion of 294.2°, and a longitude of the ascending node of 90.9°.[18][2] The last perihelion passage occurred on October 25, 1979, with the next expected around 6493 AD. The observation arc spans from 2007 to the present, enabling precise ephemerides through the JPL Small-Body Database.[18] This Sedna-like perihelion underscores its extreme detached orbit.Dynamical Evolution

The orbit of 2012 VP113 is dynamically stable against perturbations from Neptune, as its perihelion distance of approximately 80 AU places it well beyond Neptune's orbital radius of 30 AU, preventing close encounters with a minimum separation exceeding 50 AU in the current epoch. This detachment results in minimal mean-motion resonances with Neptune, limiting short-term gravitational influences from the giant planets. Over gigayear timescales, however, the orbit undergoes chaotic evolution driven by overlapping resonances and distant perturbations, though it occupies a narrow stable region in orbital parameter space where eccentricity and inclination remain nearly constant for at least 4.5 Gyr.[19] Evolutionary models propose that 2012 VP113 originated from scattering in the Neptune region during the giant planets' migration, which occurred roughly 4 Gyr ago as part of early Solar System instability scenarios like the Nice model. Alternatively, it may represent a captured interstellar object perturbed into its current orbit by passing stars in the Sun's birth cluster. N-body simulations support these origins, indicating that such objects detached from direct giant planet influence around 4 Gyr ago, with the population of inner Oort cloud bodies like 2012 VP113 forming through these mechanisms rather than ongoing scattering.[20] In the future, 2012 VP113's trajectory within the inner Oort cloud will experience gradual perihelion evolution primarily from galactic tides and occasional stellar perturbations, though its relatively low semi-major axis of approximately 273 AU results in minimal variation compared to more distant objects.[21] N-body integrations using tools like the Mercury integrator demonstrate high long-term survival, with over 98% of orbital clones remaining bound after 1 Gyr and stability extending beyond 5 Gyr for the nominal orbit, implying a survival probability exceeding 90% over the Solar System's remaining lifetime.[3]Classification and Significance

Sednoid Status

Sednoids are a class of trans-Neptunian objects characterized by detached orbits with semi-major axes greater than 150 AU and perihelia greater than 50 AU, ensuring they experience negligible gravitational influence from Neptune.[1] These objects represent the innermost portion of the Oort cloud, distinct from more inner populations like the Kuiper belt or scattered disc. 2012 VP113 qualifies as a sednoid with a perihelion of approximately 81 AU and semi-major axis of 273 AU (as of epoch October 2024), making it the second such object discovered after Sedna in 2003.[2] As of November 2025, only four sednoids are known, highlighting the rarity of this population.[3] The known sednoids share highly eccentric orbits but vary in their exact parameters, as summarized below (current osculating elements, rounded):| Object | Perihelion (AU) | Semi-major axis (AU) |

|---|---|---|

| Sedna (2003 VB12) | 76 | 507 |

| 2012 VP113 | 81 | 273 |

| Leleākūhonua (2015 TG387) | 65 | 1080 |

| 2023 KQ14 | 66 | 252 |