Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coleopter

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

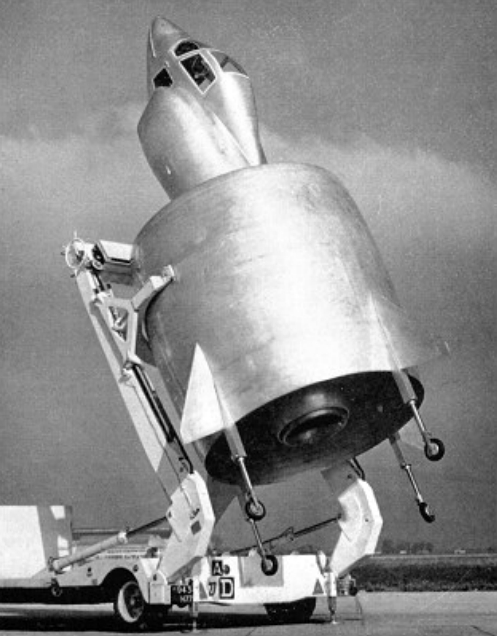

A coleopter is a type of VTOL aircraft design that uses a ducted fan as the primary fuselage of the entire aircraft. Generally they appear to be a large barrel-like extension at the rear, with a small cockpit area suspended above it. Coleopters are generally designed as tail-sitters. The term is an anglicisation of the French coléoptère "beetle" after the first actual implementation of this design, the SNECMA Coléoptère of the mid-1950s.

Early experiments

[edit]

The first design of an aircraft clearly using the coleopter concept was developed during World War II. From 1944 on, the Luftwaffe was suffering from almost continual daytime attacks on its airfields and was finding it almost impossible to conduct large-scale operations. Their preferred solution was to introduce some sort of VTOL interceptor that could be launched from any open location, and there were many proposals for such a system. Heinkel conducted a series of design studies as part of their Wespe and Lerche programs. The Wespe intended to use a Benz 2,000 hp turboprop engine, but these were not forthcoming and the Lerche used two Daimler-Benz DB 605 piston engines instead. Nothing ever came of either design.

In the immediate post-war era, most VTOL research involved helicopters. As the limitations of the simple rotary wing became clear, teams started looking for other solutions and many turned to using jet engines directly for vertical thrust. SNECMA, now Safran Aircraft Engines, developed a series of such systems as part of the SNECMA Atar Volant series during the 1950s. To further improve the design, SNECMA had Nord Aviation build an annular wing and adapted it to the last of the Volant series to produce the SNECMA Coléoptère. The Coléoptère first flew on 6 May 1959, but crashed on 25 July and no replacement was built. Even in this limited testing period, the design showed several serious problems related to the high angular momentum of the engine, which made control tricky.

In the US, Hiller Aircraft had been working on a number of ducted fan flying platforms originally designed by Charles H. Zimmerman. The Hiller VXT-8 Coleopter was a proposed annular wing VTOL aircraft designed in the late 1950s, inspired by the French SNECMA Coléoptère. After some early successes, the Army demanded a series of changes that continued to increase the size and weight of the platform, which introduced new stability problems. These generally required more size and power to correct, and no satisfactory design came from these efforts. Instead, Hiller approached the Navy with the idea of building a full coleopter design.

This emerged as the Hiller VXT-8 which was significantly similar to the SNECMA design, although it used a propeller instead of a jet engine. However, the introduction of turbine-powered helicopters like the Bell UH-1 Iroquois so significantly improved their performance over piston-powered designs that the Navy lost interest in the VXT-8 in spite of even better estimated performance. Only a mock-up was completed.

Convair Model 49

[edit]Convair selected the coleopter layout for their Model 49 proposal, entered into the Advanced Aerial Fire Support System (AAFSS).

AAFSS asked for a new high-speed helicopter design for the attack and escort roles. Submissions included gyrodynes, dual-rotor designs and similar advances on conventional designs, but nothing was as unconventional as the Model 49.

The Model 49 was based on a tri-turbine design featuring counter-rotating propellers within a shroud. Exposed areas were armored to withstand 12.7mm fire. The two-man crew was located in an articulated capsule which could either point forward of the shroud when horizontal or at right-angles to it when vertical, and pilot controls were limited to engine speed, blade angle and directional control. The design was believed by its manufacturers to be inherently more reliable than that of conventional helicopters.[1]

As a "tail-sitter" design, and like its forebear the Convair XFY-1 POGO, the Model 49 was intended to take off from a vertical orientation before transitioning to horizontal orientation for flight. Once at its destination it could transition back to vertical mode to hover and provide fire support.[2]

The design was intended to be capable of carrying multiple armament configurations, with all weapons being remotely controlled by the gunner from the crew capsule.[2] Its hardpoints consisted of two side turrets, a center turret, and two hardpoints each for two of the nacelles. All of the weapons could be used in either horizontal or vertical configuration, as well as while grounded. The turrets were mechanically prevented from firing "up" at the crew capsule while in vertical configuration. The side turrets could feature either 7.62 mm machine guns with 12,000 rounds of ammunition each, or 40mm grenade launchers with 500 rounds each.[1]

The center turret carried an XM-140 30mm cannon with 1000 rounds, with the option for a second 30mm cannon, or 500 WASP rockets. Any of the four hardpoints could carry three BGM-71 TOW missiles, or three Shillelagh missiles. Alternatively, up to one hardpoint on each of the nacelles could carry an M40A1C 106mm recoilless rifle with 18 rounds. As an alternative, the hardpoints could mount up to 1,200 gallons of additional fuel in tanks.[1]

Deemed overly complicated, the Army instead selected the Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne and Sikorsky S-66 for further development. In the end only scale models of the model 49 were ever built.[2]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Convair Model 49 helicopter - development history, photos, technical data". www.aviastar.org.

- ^ a b c "Convair Model 49 | Strange Vehicles | Diseno-Art". www.diseno-art.com.

References

[edit]- Spenser, Jay (1998). Vertical Challenge: The Hiller Aircraft Story. University of Washington Press.

- Landis, Tony; Jenkins, Dennis (2000). Lockheed AH-56A Cheyenne. Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers.

- Bradley, Robert (2013). Convair advanced designs. II, Secret fighters, attack aircraft, and unique concepts 1929-1973. Crecy Publishing. ISBN 9780859791700.