Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Compound interest

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant e |

|---|

|

| Properties |

| Applications |

| Defining e |

| People |

| Related topics |

Compound interest is interest accumulated from a principal sum and previously accumulated interest. It is the result of reinvesting or retaining interest that would otherwise be paid out, or of the accumulation of debts from a borrower.

Compound interest is contrasted with simple interest, where previously accumulated interest is not added to the principal amount of the current period. Compounded interest depends on the simple interest rate applied and the frequency at which the interest is compounded.

Compounding frequency

[edit]The compounding frequency is the number of times per given unit of time the accumulated interest is capitalized, on a regular basis. The frequency could be yearly, half-yearly, quarterly, monthly, weekly, daily, continuously, or not at all until maturity.

For example, monthly capitalization with interest expressed as an annual rate means that the compounding frequency is 12, with time periods measured in months.

Annual equivalent rate

[edit]To help consumers compare retail financial products more fairly and easily, many countries require financial institutions to disclose the annual compound interest rate on deposits or advances on a comparable basis. The interest rate on an annual equivalent basis may be referred to variously in different markets as effective annual percentage rate (EAPR), annual equivalent rate (AER), effective interest rate, effective annual rate, annual percentage yield and other terms. The effective annual rate is the total accumulated interest that would be payable up to the end of one year, divided by the principal sum. These rates are usually the annualised compound interest rate alongside charges other than interest, such as taxes and other fees.

Examples

[edit]

$266,864 in total dividend payments over 40 years

Dividends were not reinvested in this scenario

- The interest on corporate bonds and government bonds is usually payable twice yearly. The amount of interest paid every six months is the disclosed interest rate divided by two and multiplied by the principal. The yearly compounded rate is higher than the disclosed rate.

- Canadian mortgage loans are generally compounded semi-annually with monthly or more frequent payments.[1]

- U.S. mortgages use an amortizing loan, not compound interest. With these loans, an amortization schedule is used to determine how to apply payments toward principal and interest. Interest generated on these loans is not added to the principal, but rather is paid off monthly as the payments are applied.

- It is sometimes mathematically simpler, for example, in the valuation of derivatives, to use continuous compounding. Continuous compounding in pricing these instruments is a natural consequence of Itô calculus, where financial derivatives are valued at ever-increasing frequency, until the limit is approached and the derivative is valued in continuous time.

History

[edit]Compound interest was known to ancient civilisations, but the first traces of mathematicians analysing it are from medieval era. A clay tablet from Babylon, dating from about 2000–1700 B.C., might be the first display of the compound interest problem. [2]

Compound interest when charged by lenders was once regarded as the worst kind of usury and was severely condemned by Roman law and the common laws of many other countries.[3]

The Florentine merchant Francesco Balducci Pegolotti provided a table of compound interest in his book Pratica della mercatura of about 1340. It gives the interest on 100 lire, for rates from 1% to 8%, for up to 20 years.[4] The Summa de arithmetica of Luca Pacioli (1494) gives the Rule of 72, stating that to find the number of years for an investment at compound interest to double, one should divide the interest rate into 72.

Richard Witt's book Arithmeticall Questions, published in 1613, was a landmark in the history of compound interest. It was wholly devoted to the subject (previously called anatocism), whereas previous writers had usually treated compound interest briefly in just one chapter in a mathematical textbook. Witt's book gave tables based on 10% (the maximum rate of interest allowable on loans) and other rates for different purposes, such as the valuation of property leases. Witt was a London mathematical practitioner and his book is notable for its clarity of expression, depth of insight, and accuracy of calculation, with 124 worked examples.[5][6]

Jacob Bernoulli discovered the constant in 1683 by studying a question about compound interest.

In the 19th century, and possibly earlier, Persian merchants used a slightly modified linear Taylor approximation to the monthly payment formula that could be computed easily in their heads.[7] In modern times, Albert Einstein's supposed quote regarding compound interest rings true. "He who understands it earns it; he who doesn't pays it"[8]. Einstein is also claimed to describe compound interest the 8th wonder of the World [9].

Calculation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

Periodic compounding

[edit]The total accumulated value, including the principal sum plus compounded interest , is given by the formula:[10][11]

where:

- A is the final amount

- P is the original principal sum

- r is the nominal annual interest rate

- n is the compounding frequency (1: annually, 12: monthly, 52: weekly, 365: daily)[12]

- t is the overall length of time the interest is applied (expressed using the same time units as r, usually years).

The total compound interest generated is the final amount minus the initial principal, since the final amount is equal to principal plus interest:[13]

Accumulation function

[edit]Since the principal P is simply a coefficient, it is often dropped for simplicity, and the resulting accumulation function is used instead. The accumulation function shows what $1 grows to after any length of time. The accumulation function for compound interest is:

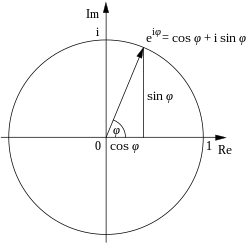

Continuous compounding

[edit]When the number of compounding periods per year increases without limit, continuous compounding occurs, in which case the effective annual rate approaches an upper limit of er − 1. Continuous compounding can be regarded as letting the compounding period become infinitesimally small, achieved by taking the limit as n goes to infinity. The amount after t periods of continuous compounding can be expressed in terms of the initial amount P0 as:

Force of interest

[edit]As the number of compounding periods tends to infinity in continuous compounding, the continuous compound interest rate is referred to as the force of interest . For any continuously differentiable accumulation function a(t), the force of interest, or more generally the logarithmic or continuously compounded return, is a function of time as follows:

This is the logarithmic derivative of the accumulation function.

Conversely: (Since , this can be viewed as a particular case of a product integral.)

When the above formula is written in differential equation format, then the force of interest is simply the coefficient of amount of change:

For compound interest with a constant annual interest rate r, the force of interest is a constant, and the accumulation function of compounding interest in terms of force of interest is a simple power of e: or

The force of interest is less than the annual effective interest rate, but more than the annual effective discount rate. It is the reciprocal of the e-folding time.

A way of modeling the force of inflation is with Stoodley's formula: where p, r and s are estimated.

Compounding basis

[edit]To convert an interest rate from one compounding basis to another compounding basis, so that

use

where r1 is the interest rate with compounding frequency n1, and r2 is the interest rate with compounding frequency n2.

When interest is continuously compounded, use

where is the interest rate on a continuous compounding basis, and r is the stated interest rate with a compounding frequency n.

Monthly amortized loan or mortgage payments

[edit]The interest on loans and mortgages that are amortized—that is, have a smooth monthly payment until the loan has been paid off—is often compounded monthly. The formula for payments is found from the following argument.

Exact formula for monthly payment

[edit]An exact formula for the monthly payment () is or equivalently

where:

- = monthly payment

- = principal

- = monthly interest rate

- = number of payment periods

Spreadsheet formula

[edit]In spreadsheets, the PMT() function is used. The syntax is:

PMT(interest_rate, number_payments, present_value, future_value, [Type])

Approximate formula for monthly payment

[edit]A formula that is accurate to within a few percent can be found by noting that for typical U.S. note rates ( and terms =10–30 years), the monthly note rate is small compared to 1. so that the which yields the simplification:

which suggests defining auxiliary variables

Here is the monthly payment required for a zero–interest loan paid off in installments. In terms of these variables the approximation can be written .

Let . The expansion is valid to better than 1% provided .

Example of mortgage payment

[edit]For a $120,000 mortgage with a term of 30 years and a note rate of 4.5%, payable monthly, we find:

which gives

so that

The exact payment amount is so the approximation is an overestimate of about a sixth of a percent.

Monthly deposits

[edit]Given a principal deposit and a recurring deposit, the total return of an investment can be calculated via the compound interest gained per unit of time. If required, the interest on additional non-recurring and recurring deposits can also be defined within the same formula (see below).[14]

- = principal deposit

- = rate of return (monthly)

- = monthly deposit, and

- = time, in months

The compound interest for each deposit is: Adding all recurring deposits over the total period t, (i starts at 0 if deposits begin with the investment of principal; i starts at 1 if deposits begin the next month): Recognizing the geometric series: and applying the closed-form formula (common ratio :):

If two or more types of deposits occur (either recurring or non-recurring), the compound value earned can be represented as

where C is each lump sum and k are non-monthly recurring deposits, respectively, and x and y are the differences in time between a new deposit and the total period t is modeling.

A practical estimate for reverse calculation of the rate of return when the exact date and amount of each recurring deposit is not known, a formula that assumes a uniform recurring monthly deposit over the period, is:[15] or

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Interest Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. I-15, s. 6: Interest on Moneys Secured by Mortgage on Real Property or Hypothec on Immovables". Justice Laws Website. Department of Justice (Canada). 2002-12-31. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2024-08-14.

- ^ Lewis, C.G. (24 December 2019). "The emergence of compound interest". British Actuarial Journal. 24. doi:10.1017/S1357321719000254.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Interest". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Interest". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

- ^ Evans, Allan (1936). Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, La Pratica della Mercatura. Cambridge, Massachusetts. pp. 301–2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lewin, C G (1970). "An Early Book on Compound Interest - Richard Witt's Arithmeticall Questions". Journal of the Institute of Actuaries. 96 (1): 121–132. doi:10.1017/S002026810001636X.

- ^ Lewin, C G (1981). "Compound Interest in the Seventeenth Century". Journal of the Institute of Actuaries. 108 (3): 423–442. doi:10.1017/S0020268100040865.

- ^ Milanfar, Peyman (1996). "A Persian Folk Method of Figuring Interest". Mathematics Magazine. 69 (5): 376. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1996.11996479.

- ^ Schleckser, Jim (January 21, 2020). "Why Einstein Considered Compound Interest the Most Powerful Force in the Universe: Is the power of compound interest really the 8th Wonder of the World?". Inc.

- ^ "Compound Interest Calculator". Investing insiders. Retrieved 14 October 2025.

- ^ "Compound Interest Formula". qrc.depaul.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Investopedia Staff (2003-11-19). "Continuous Compounding". Investopedia. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ JAMES CHEN (2024-08-01). "Compounding Interest: Formulas and Examples". Investopedia. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ "Compound Interest Formula - Explained". www.thecalculatorsite.com. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ "Using Compound Interest to Optimize Investment Spread".

- ^ http://moneychimp.com/features/portfolio_performance_calculator.htm "recommended by The Four Pillars of Investing and The Motley Fool"

Compound interest

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Principles

Compound interest refers to the process by which interest is calculated on the initial principal amount plus the accumulated interest from previous periods, allowing earnings to generate further earnings over time.[1] This mechanism results in the balance growing at an accelerating rate, as each period's interest is added to the principal for the next calculation.[8] In this system, the principal represents the initial sum of money invested or borrowed, serving as the starting point for growth.[9] The interest rate is expressed as a percentage applied per specified time period, such as annually or monthly, determining the proportional increase in each cycle.[10] Time periods, or compounding intervals, define how frequently the interest is calculated and added, influencing the overall accumulation.[2] The core principle of compound interest lies in its promotion of exponential growth through the reinvestment of earnings, where the balance expands nonlinearly unlike fixed linear increments in alternative systems.[11] This self-reinforcing process amplifies returns over extended durations, as prior gains become part of the base for future calculations.[12] Intuitively, compound interest operates like a snowball rolling downhill, where the initial mass gradually accumulates more snow with each turn, leading to progressively larger and faster growth.[13] This analogy highlights how modest beginnings can yield substantial results through consistent reinvestment.[1]Comparison with Simple Interest

Simple interest is calculated solely on the initial principal amount, without adding any accrued interest to the principal for future calculations, resulting in a linear accumulation of value over time.[14] This approach produces a steady, predictable growth pattern where the interest earned remains proportional to the original sum and the duration of the investment or loan.[15] In contrast, compound interest builds on both the principal and previously earned interest, leading to exponential growth that accelerates as time progresses, while simple interest follows an arithmetic progression that grows at a constant rate.[16] This fundamental difference means that under compound interest, the rate of increase compounds over periods, creating a curve that steepens over time on a graph, whereas simple interest traces a straight line.[17] Over extended periods, the exponential nature of compound interest causes it to vastly outpace the linear growth of simple interest, with investments or debts potentially doubling multiple times faster in relative terms.[18] For instance, at a fixed rate, simple interest might require a consistent timeframe to double the principal regardless of starting point, but compound interest achieves doubling in a shorter fixed timeframe than simple interest at the same rate, amplifying long-term outcomes in savings or liabilities.[19] A common misconception is that compound interest solely benefits savers, but it equally applies to debt scenarios, where unpaid interest accrues on the growing balance, potentially leading to rapid escalation of obligations if not managed.[20] This dual application underscores its role as a mechanism that rewards or penalizes based on whether it operates in favor of the borrower or lender.[21]Historical Development

Ancient and Early Modern Origins

The earliest evidence of compound-like calculations in lending practices dates back to ancient Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE, during the Old Babylonian period. Clay tablets from this era, such as those analyzed in mathematical reconstructions, demonstrate computations that approximate compound interest by accruing interest on accumulated amounts over multiple periods, often in agricultural and commercial loans measured in shekels or barley. These practices were embedded in a sexagesimal system that facilitated periodic interest additions, reflecting the economic needs of temple and palace economies where debts could grow exponentially if unpaid.[22][23] In ancient India, concepts akin to interest on interest appear in texts from the late Vedic and post-Vedic periods, around 600 BCE onward, under terms like vriddhi (growth) and cakravriddhi (cyclic increase), which described compounding in debt and loan scenarios. These references, found in legal and economic treatises such as the Manusmṛti, regulated compound interest rates to prevent excessive debt burdens, integrating it into broader principles of dharma and commerce. While explicit mathematical formulas were not formalized, these ideas supported practical calculations in trade and agriculture, emphasizing balanced economic growth.[24][25] Similar notions of compounding through iterative growth are noted in ancient Chinese mathematical traditions, though primarily illustrative rather than systematic; for instance, legendary problems like the wheat and chessboard paradox from folklore highlight exponential accumulation, influencing later economic thought without direct textual evidence of routine application in early works like the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.[26] During the Greco-Roman period, the use of compound interest was limited by widespread prohibitions on usury, rooted in philosophical and religious critiques. Aristotle, in his Politics, condemned the practice as unnatural, arguing that money should not "breed" more money since it lacks the productive capacity of natural resources like land or livestock, viewing it as a distortion of economic purpose. This perspective, echoed in Roman law under emperors like Justinian, restricted compounding to exceptional cases, prioritizing simple interest in civic and familial transactions.[27] In medieval Europe, Islamic scholars played a pivotal role in advancing arithmetic essential for interest calculations, bridging ancient knowledge to the Renaissance. Al-Khwarizmi's Hisab al-jabr wal-muqabala (c. 820 CE) systematized algebraic methods for solving equations that could model debt accumulation, facilitating computations in commerce despite Islamic bans on riba (usury) by focusing on equitable partnerships. This work influenced European mathematics through translations, culminating in the reintroduction of compound interest via Fibonacci's Liber Abaci (1202), which provided practical algorithms for iterative interest on loans, marking a shift toward widespread mercantile application.[28][29][30] Building on these foundations, Italian mathematicians in the 14th and 15th centuries advanced compound interest calculations significantly. Around 1340, Antonio de' Pégolotti developed early tables for compound interest, utilized by Florentine banking houses like the Bardi family for commercial purposes. These unpublished tables represented a practical tool for merchants handling long-term loans and investments. Further progress came with Luca Pacioli's Summa de arithmetica (1494), which included solutions to complex compound interest problems using algebraic methods and referenced existing tables, promoting the concept's integration into double-entry bookkeeping and broader financial practice.[6]Formalization in the 17th Century

In the 17th century, the economic landscape of Europe was transformed by the rise of mercantilism, a doctrine emphasizing state accumulation of wealth through trade surpluses and colonial expansion, which spurred the formation of joint-stock companies to finance large-scale ventures.[31] These entities, such as the English East India Company established in 1600, required sophisticated methods for calculating returns on investments over extended periods, including compound interest to account for reinvested profits in high-risk, long-distance trade. This practical demand elevated compound interest from rudimentary applications to a formalized analytical tool essential for assessing annuities, leases, and equity stakes in emerging capitalist structures.[32] A pivotal advancement came in 1613 with the publication of Arithmeticall Questions by Richard Witt, an English scrivener, which provided the first comprehensive set of tables dedicated to compound interest computations in English.[32] The book addressed practical scenarios like valuing annuities and fee simples under compounding at rates such as 10%, enabling merchants and investors to perform accurate valuations without manual trial-and-error calculations.[32] Witt's work marked a shift toward standardized, tabular methods that supported the growing complexity of financial transactions in mercantile economies.[32] Further mathematical rigor was introduced by Jacob Bernoulli in his 1683 analysis of continuous compounding, where he examined the limit of the expression as approaches infinity, recognizing it converged to a finite constant between 2 and 3.[33] This investigation arose from modeling wealth growth under infinitely frequent interest reinvestment, laying the groundwork for understanding exponential growth in financial contexts.[34] Bernoulli's insight formalized compound interest as an asymptotic process, influencing subsequent developments in calculus and actuarial science.[33] Bernoulli's posthumously published Ars Conjectandi in 1713 extended these ideas by linking repeated compounding to the base of the natural logarithm, , without deriving an explicit formula for continuous interest.[35] In this foundational probability treatise, he integrated compounding dynamics with probabilistic models for risk assessment, underscoring its relevance to economic forecasting and insurance.[36] This connection highlighted compound interest's role in quantifying uncertainty in long-term investments, aligning with the era's expanding financial instruments.[36]Core Mathematical Formulas

Periodic Compounding Formula

The periodic compounding formula describes the growth of an investment or loan where interest is added to the principal at discrete intervals, such as monthly or quarterly, allowing the interest to earn further interest in subsequent periods. This contrasts with simple interest by incorporating the exponential nature of growth through repeated multiplications./06%3A_Mathematics_of_Finance/6.02%3A_Compound_Interest) The standard formula for the final amount after time is given by: where is the initial principal (the starting amount), is the nominal annual interest rate (expressed as a decimal), is the number of compounding periods per year, and is the time the money is invested or borrowed, measured in years. This formula assumes basic algebraic operations, particularly exponentiation, to compute the compounded value.[37]/06%3A_Mathematics_of_Finance/6.02%3A_Compound_Interest) Here, represents the base amount upon which interest is calculated, serving as the starting point for growth. The term denotes the interest rate per compounding period, dividing the annual rate by the frequency to reflect smaller, more frequent accruals. The exponent counts the total number of compounding periods over the investment duration, amplifying the growth factor multiplicatively. Increasing —such as from annual to quarterly or daily compounding—raises the effective growth rate by applying interest more often, though the nominal rate remains fixed, leading to higher final amounts for the same , , and . For instance, with , , , annual compounding () yields , while quarterly () yields approximately , demonstrating the impact of frequency.[37]/06%3A_Mathematics_of_Finance/6.02%3A_Compound_Interest) The derivation begins with the recursive application of simple interest per period. Start with principal ; after the first period, the amount becomes . In the second period, interest is applied to this new balance, yielding . Continuing this process for periods results in the general form . This recursive multiplication forms a geometric series where each term is the previous multiplied by the common ratio , and the sum (or final term in this endpoint calculation) is captured by the exponentiation, avoiding the need to expand the full series explicitly.[37]/06%3A_Mathematics_of_Finance/6.02%3A_Compound_Interest)Continuous Compounding and Limit Derivation

Continuous compounding represents the theoretical limit of compound interest as the frequency of compounding increases without bound, effectively adding interest at every instant. This concept arises from considering the periodic compounding formula, where interest is added m times per year, and then taking the limit as m approaches infinity. In this scenario, the amount A accumulated from an initial principal P at nominal annual rate r over time t years satisfies the limit expression that converges to an exponential form.[38] The derivation begins with the periodic compounding amount , where n is the number of compounding periods per year. As n tends to infinity, this expression approaches , where e is the base of the natural logarithm, approximately 2.71828. This limit can be shown using the definition of the exponential function, where for x = rt; thus, the growth factor becomes . The process models instantaneous compounding, as interest is continuously reinvested, leading to smoother and more rapid accumulation compared to discrete periods.[38][33] The discovery of this limiting behavior and the constant e in the context of continuous compounding is attributed to Jacob Bernoulli, who in 1683 analyzed the problem of compound interest with increasingly frequent intervals and observed that the limit of as n approaches infinity lies between 2 and 3, though he did not compute its exact value. Bernoulli's work, published posthumously in his 1713 book Ars Conjectandi, marked an early recognition of e's role in financial growth models.[33] For a fixed nominal annual interest rate r, continuous compounding produces the highest possible yield among all compounding frequencies, as it maximizes the effective growth by eliminating the gaps between interest additions. This makes the formula the upper bound for accumulation in theoretical models of interest.[39]Accumulation Function

In financial mathematics, the accumulation function, denoted , represents the growth factor applied to an initial principal to determine the amount at time , such that the accumulated value is . This function quantifies the proportional increase in value from time 0 to under compound interest, assuming reinvestment of earnings. It provides a general framework for modeling investment growth over continuous or discrete time periods.[40] For periodic compounding at an effective interest rate per period, the accumulation function takes the form , where is measured in periods. This exponential expression captures the iterative multiplication of the principal by the growth factor at each compounding interval.[41] In the continuous compounding case, particularly when interest rates vary over time, the accumulation function generalizes to , where is the force of interest at time . This integral form accounts for instantaneously varying rates, deriving from the differential equation with initial condition .[42] The accumulation function exhibits key properties under positive interest rates: it is strictly monotonic increasing, as for , ensuring continuous growth. Additionally, it is convex, reflecting the accelerating effect of compounding, where the second derivative holds for non-decreasing , or strictly positive for constant . These properties underscore the function's role in capturing the nonlinear nature of compounded returns.[43]Interest Rate Measures

Effective Annual Rate

The effective annual rate (EAR), also known as the annual percentage yield (APY), represents the true annual interest rate earned or paid on an investment or loan after accounting for intra-year compounding. It standardizes the return to an annual basis, enabling direct comparisons between financial products with varying compounding frequencies. The EAR is calculated using the formula: where is the nominal annual interest rate (expressed as a decimal) and is the number of compounding periods per year.[40] To compute the EAR, first divide the nominal rate by the compounding frequency to find the periodic rate, then add 1 to obtain the growth factor per period. Raise this growth factor to the power of to annualize it, and subtract 1 to isolate the effective rate. For instance, with a nominal rate of 5% () compounded semiannually (), the periodic rate is 0.025, the growth factor is 1.025, and , yielding an EAR of 5.0625%. This process reveals how more frequent compounding increases the effective yield beyond the nominal rate.[40] The primary importance of the EAR lies in its ability to facilitate apples-to-apples comparisons across investments or loans with different compounding schedules, ensuring borrowers and savers understand the actual cost or return without distortion from nominal figures. By converting all rates to an equivalent annual effective basis, it highlights the impact of compounding frequency on overall growth. The following table illustrates EAR values for a nominal rate of 5% under various compounding frequencies, demonstrating the progressive increase in effective yield:| Compounding Frequency () | Description | EAR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Annually | 5.0000 |

| 2 | Semiannually | 5.0625 |

| 4 | Quarterly | 5.0945 |

| 12 | Monthly | 5.1162 |

| ∞ | Continuous | 5.1271 |

Nominal Rate and Compounding Frequency

The nominal interest rate, commonly denoted as , represents the stated annual percentage rate (APR) quoted by financial institutions for loans, savings, or investments, without adjustment for intra-year compounding or fees in the case of deposits.[44] This rate serves as the baseline for calculating interest accrual over a year, such as a 5% nominal rate indicating the uncompounded annual cost or yield.[45] Compounding frequency, denoted as , specifies the number of periods per year in which interest is calculated and added to the principal balance, directly influencing the total interest earned or paid.[8] Higher frequencies lead to greater overall growth because interest compounds on previously accrued interest more often, though the incremental benefit decreases as frequency increases due to diminishing returns.[8] Common compounding frequencies in finance include annual (), semiannual (), quarterly (), monthly (), and daily (), with daily compounding often used for high-yield savings accounts and certificates of deposit to maximize returns.[46] In consumer finance, regulatory standards distinguish the nominal rate, typically disclosed as APR for borrowing products to include fees but exclude compounding effects, from the annual percentage yield (APY) used for deposits to reflect compounding.[47] Under the U.S. Truth in Lending Act (TILA) and its implementing Regulation Z, lenders must disclose APR to promote transparency in credit costs, while the Truth in Savings Act (Regulation DD) mandates APY disclosures for deposit accounts to inform savers of effective yields; these requirements remain in effect as of 2025 with no substantive changes.[48][49]Force of Interest

The force of interest, denoted , represents the instantaneous rate of growth in the continuous compounding model and is defined as the relative rate of change of the accumulation function , expressed mathematically as .[50] This formulation is equivalent to the derivative of the natural logarithm of the accumulation function, , providing a precise measure of the compounding process at any instant in time.[51] In financial mathematics, this concept arises naturally from the limit of compound interest as the compounding frequency approaches infinity, emphasizing continuous rather than discrete growth.[52] When the force of interest is constant, denoted simply as , the accumulation function takes the exponential form , assuming an initial value of .[50] This corresponds directly to continuous compounding, where the effective continuous rate governs the growth such that the amount for principal .[53] The constant force simplifies calculations in scenarios with uniform instantaneous rates, aligning with the exponential nature of uninterrupted compounding over time. For variable forces of interest , the accumulation function is obtained by integrating the force over the relevant period: .[50] This integral form allows modeling of time-dependent interest environments, such as those influenced by fluctuating economic conditions, where the total growth reflects the cumulative effect of instantaneous rates.[51] The force of interest relates to the effective annual rate over a one-year period through the equation , or equivalently, .[50] This connection bridges continuous and discrete measures, showing how the instantaneous rate equates to the logarithmic transform of the effective rate, facilitating comparisons between compounding models.[53]Practical Applications

Savings and Investment Growth

Compound interest plays a pivotal role in the growth of savings and investments by allowing earnings to generate additional returns over time. For a single lump-sum investment, the future value is calculated using the periodic compounding formula , where is the initial principal, is the nominal annual interest rate, is the number of compounding periods per year, and is the time in years.[54] This formula projects how an initial deposit in a savings account or investment vehicle, such as a certificate of deposit or stock index fund, accumulates value through reinvested interest. For example, banks and financial institutions apply this to high-yield savings accounts, where more frequent compounding (e.g., monthly) accelerates growth compared to annual compounding. In investing contexts, this principle is particularly effective when using low-cost index funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which enable diversified portfolios tailored to an investor's risk tolerance, thereby reducing overall risk through exposure to a broad range of assets.[55][56] A classic illustration of this growth in a retirement context is an initial investment of $10,000 earning 7% annual interest compounded annually over 30 years. To arrive at the future value, substitute into the formula: . First, compute , then multiply by the principal to yield approximately $76,123. This demonstrates how the investment more than septuples, with the majority of the final amount stemming from compounded earnings rather than the original principal.[57] Such projections underscore the potential for long-term wealth building in retirement accounts like 401(k)s or IRAs, where historical stock market returns have averaged around 7% after inflation.[58] To project future wealth growth assuming compound interest on both an initial investment and regular annual surpluses, the future value can be calculated using the formula , where is the initial wealth, is the annual surplus added at the end of each year, is the annual interest rate, and is the number of years. This combines the compounded growth of the initial principal with the future value of an ordinary annuity for the regular contributions. For instance, assuming an 8% annual return, the Rule of 72 approximation indicates that wealth doubles roughly every 9 years, as 72 divided by 8 equals 9.[59][18] The power of compounding is amplified by starting early, as the exponential effect allows smaller initial amounts to grow substantially over decades. For instance, beginning savings in one's 20s rather than 40s can lead to significantly larger nest eggs due to the extended time for interest to compound.[60] However, real-world factors influence net growth: taxes on interest earned in taxable accounts are treated as ordinary income, potentially reducing effective returns by up to 37% depending on the taxpayer's bracket.[61] Additionally, in 2025, with U.S. inflation projected at 3.1%, investors must adjust nominal growth for purchasing power erosion, emphasizing the need for returns exceeding inflation to preserve wealth.[62] To illustrate the extreme potential of frequent compounding, consider a hypothetical scenario with a 5% daily return compounded daily over one year. Applying the formula , the investment would grow to approximately , equivalent to an annual return of over 5.39 billion percent.[63] However, such returns are highly unrealistic in practical trading or investing contexts. Professional traders typically target annual returns of 10-30%, as consistent daily gains of this magnitude are unattainable due to market volatility, which often leads to losses exceeding gains and potential account liquidation.[64][65]Amortized Loans and Mortgages

In amortized loans, borrowers make fixed periodic payments that encompass both interest and a portion of the principal, ensuring the loan is fully repaid by the end of the term. The interest portion of each payment is computed on the outstanding principal balance, which decreases over time as principal repayments accumulate, leveraging the mechanics of compound interest on the declining debt. The fixed monthly payment for such a loan is determined by the formula where is the initial principal, is the monthly interest rate (annual rate divided by 12), and is the total number of payments. This equation arises from equating the present value of the loan to the present value of the annuity of payments, solving for the payment amount that amortizes the debt exactly over periods. An amortization schedule details the breakdown of each payment into interest and principal components, revealing a front-loaded structure: early payments primarily cover interest due to the higher initial balance, while later payments allocate more to principal as the balance shrinks. For instance, in the first payment, nearly the entire amount may go toward interest, but by the final payment, the interest share is minimal. Mortgages, a common form of amortized loan, typically span 15 to 30 years with monthly payments. As of November 13, 2025, the average U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage stands at 6.24%.[66] For a $300,000 mortgage at this rate over 30 years (360 payments), the monthly payment is $1,845.20, resulting in total payments of $664,272 and cumulative interest of $364,272—more than the original principal due to compounding effects.[67] This illustrates how longer terms amplify total interest costs despite lower monthly outlays.Regular Deposits and Annuities

Regular deposits into an investment account that earns compound interest form the basis of an annuity, where a fixed payment is made at regular intervals, allowing each deposit to grow over time. This structure is commonly used in savings plans, retirement accounts, and pension funds, enabling systematic wealth accumulation through the power of compounding.[68] The future value of an ordinary annuity, where payments occur at the end of each period, is calculated using the formula: Here, represents the periodic payment amount, is the interest rate per period, and is the total number of periods. This formula accounts for the compounding effect on each deposit from the time it is made until the end of the annuity term.[68][69] In contrast, an annuity due involves payments at the beginning of each period, providing an additional compounding period for each deposit compared to an ordinary annuity. The future value for an annuity due is obtained by multiplying the ordinary annuity formula by : This adjustment reflects the earlier timing of payments, resulting in a higher future value. Ordinary annuities are typical for most savings plans, while annuities due are more common in lease agreements or certain insurance products.[68][70] For illustration, consider monthly deposits of $500 into an account earning 5% annual interest compounded monthly over 20 years. The periodic rate , and . Applying the ordinary annuity formula yields: This demonstrates how regular contributions can substantially grow to nearly $200,000, far exceeding the total deposits of $120,000, due to compounding.[68] Another example is investing $5,000 annually at a 7% return compounded annually over 30 years, which would grow to approximately $472,304. This illustrates the exponential growth of compound interest and how starting early amplifies the benefits by providing more time for earnings to generate further returns.[57] To further illustrate the impact of higher returns on monthly deposits, consider fixed monthly investments at a 10% annual return compounded monthly. For $1,000 monthly deposits over 20 years (n=240, r=0.10/12≈0.008333), the future value is approximately $687,347. For $2,000 monthly deposits under the same conditions, the future value is approximately $1,374,694. These calculations use the ordinary annuity formula and highlight how compounding at higher rates accelerates growth beyond the total principal invested.[57][63] Additionally, the formula can be rearranged to determine the required monthly deposit to reach a target future value. For example, to accumulate $1,000,000 over 20 years at 10% annual return compounded monthly, the required monthly deposit is approximately $1,455. Over 30 years under the same rate (n=360), it is approximately $437. These figures demonstrate the sensitivity of required contributions to time horizon in annuity planning.[57][63] A practical application of regular deposits with varying contribution amounts is dollar-cost averaging (DCA) in investments such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs), where contributions increase over time to reflect rising income or commitment. For instance, consider monthly investments of $750 for the first 3 years (36 months), $1,200 for the next 4 years (48 months), and $1,700 for the final 3 years (36 months), totaling approximately $146,000 invested over 10 years. Assuming monthly compounding and end-of-month deposits with a historical annual return of 8% (periodic rate ), the future value is approximately $216,000. At a 6% annual return, it yields about $188,000, and at 10%, about $238,000. These calculations use the future value of annuity formula applied sequentially to each contribution period and demonstrate how increasing contributions enhance growth through compounding, though actual returns are not guaranteed and may vary based on market conditions.[71] Annuities can also be growing, where deposit amounts increase by a constant growth rate each period, often to account for inflation or rising income. The future value of a growing ordinary annuity is given by: assuming . This formula extends the standard annuity model to scenarios like escalating retirement contributions, providing a more realistic projection for long-term planning.[72]Illustrations and Approximations

Numerical Examples

To illustrate the application of compound interest, consider an initial principal of $1,000 invested at an annual nominal interest rate of 6%, compounded quarterly over 5 years. The quarterly interest rate is 6%/4 = 1.5%, or 0.015 in decimal form. The balance after each quarter is calculated as , where , , , and is the time in years, but for step-by-step computation, apply the formula iteratively per period. Starting with the initial balance of $1,000 at the end of year 0: After year 1 (4 quarters): After year 2: After year 3: After year 4: After year 5: The following table summarizes the end-of-year balances, rounded to two decimal places for currency representation:| Year | Balance ($) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1,000.00 |

| 1 | 1,061.68 |

| 2 | 1,127.00 |

| 3 | 1,196.50 |

| 4 | 1,270.24 |

| 5 | 1,348.85 |

- Year 1:

- Year 2:

- Year 3:

- Year 4:

- Year 5:

.gif/250px-Compound_interest_(English).gif)

.gif)

![{\displaystyle r_{2}=\left[\left(1+{\frac {r_{1}}{n_{1}}}\right)^{\frac {n_{1}}{n_{2}}}-1\right]{n_{2}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58a91c24fd5ef43e7b584e4f740ff3dee69bdfdc)