Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Computational complexity theory

View on Wikipedia

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, computational complexity theory focuses on classifying computational problems according to their resource usage, and explores the relationships between these classifications. A computational problem is a task solved by a computer. A computation problem is solvable by mechanical application of mathematical steps, such as an algorithm.

A problem is regarded as inherently difficult if its solution requires significant resources, whatever the algorithm used. The theory formalizes this intuition, by introducing mathematical models of computation to study these problems and quantifying their computational complexity, i.e., the amount of resources needed to solve them, such as time and storage. Other measures of complexity are also used, such as the amount of communication (used in communication complexity), the number of gates in a circuit (used in circuit complexity) and the number of processors (used in parallel computing). One of the roles of computational complexity theory is to determine the practical limits on what computers can and cannot do. The P versus NP problem, one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems,[1] is part of the field of computational complexity.

Closely related fields in theoretical computer science are analysis of algorithms and computability theory. A key distinction between analysis of algorithms and computational complexity theory is that the former is devoted to analyzing the amount of resources needed by a particular algorithm to solve a problem, whereas the latter asks a more general question about all possible algorithms that could be used to solve the same problem. More precisely, computational complexity theory tries to classify problems that can or cannot be solved with appropriately restricted resources. In turn, imposing restrictions on the available resources is what distinguishes computational complexity from computability theory: the latter theory asks what kinds of problems can, in principle, be solved algorithmically.

Computational problems

[edit]

Problem instances

[edit]A computational problem can be viewed as an infinite collection of instances together with a set (possibly empty) of solutions for every instance. The input string for a computational problem is referred to as a problem instance, and should not be confused with the problem itself. In computational complexity theory, a problem refers to the abstract question to be solved. In contrast, an instance of this problem is a rather concrete utterance, which can serve as the input for a decision problem. For example, consider the problem of primality testing. The instance is a number (e.g., 15) and the solution is "yes" if the number is prime and "no" otherwise (in this case, 15 is not prime and the answer is "no"). Stated another way, the instance is a particular input to the problem, and the solution is the output corresponding to the given input.

To further highlight the difference between a problem and an instance, consider the following instance of the decision version of the travelling salesman problem: Is there a route of at most 2000 kilometres passing through all of Germany's 14 largest cities? The quantitative answer to this particular problem instance is of little use for solving other instances of the problem, such as asking for a round trip through 14 sites in Milan whose total length is at most 10 km. For this reason, complexity theory addresses computational problems and not particular problem instances.

Representing problem instances

[edit]When considering computational problems, a problem instance is a string over an alphabet. Usually, the alphabet is taken to be the binary alphabet (i.e., the set {0,1}), and thus the strings are bitstrings. As in a real-world computer, mathematical objects other than bitstrings must be suitably encoded. For example, integers can be represented in binary notation, and graphs can be encoded directly via their adjacency matrices, or by encoding their adjacency lists in binary.

Even though some proofs of complexity-theoretic theorems regularly assume some concrete choice of input encoding, one tries to keep the discussion abstract enough to be independent of the choice of encoding. This can be achieved by ensuring that different representations can be transformed into each other efficiently.

Decision problems as formal languages

[edit]

Decision problems are one of the central objects of study in computational complexity theory. A decision problem is a type of computational problem where the answer is either yes or no (alternatively, 1 or 0). A decision problem can be viewed as a formal language, where the members of the language are instances whose output is yes, and the non-members are those instances whose output is no. The objective is to decide, with the aid of an algorithm, whether a given input string is a member of the formal language under consideration. If the algorithm deciding this problem returns the answer yes, the algorithm is said to accept the input string, otherwise it is said to reject the input.

An example of a decision problem is the following. The input is an arbitrary graph. The problem consists in deciding whether the given graph is connected or not. The formal language associated with this decision problem is then the set of all connected graphs—to obtain a precise definition of this language, one has to decide how graphs are encoded as binary strings.

Function problems

[edit]A function problem is a computational problem where a single output (of a total function) is expected for every input, but the output is more complex than that of a decision problem—that is, the output is not just yes or no. Notable examples include the traveling salesman problem and the integer factorization problem.

It is tempting to think that the notion of function problems is much richer than the notion of decision problems. However, this is not really the case, since function problems can be recast as decision problems. For example, the multiplication of two integers can be expressed as the set of triples such that the relation holds. Deciding whether a given triple is a member of this set corresponds to solving the problem of multiplying two numbers.

Measuring the size of an instance

[edit]To measure the difficulty of solving a computational problem, one may wish to see how much time the best algorithm requires to solve the problem. However, the running time may, in general, depend on the instance. In particular, larger instances will require more time to solve. Thus the time required to solve a problem (or the space required, or any measure of complexity) is calculated as a function of the size of the instance. The input size is typically measured in bits. Complexity theory studies how algorithms scale as input size increases. For instance, in the problem of finding whether a graph is connected, how much more time does it take to solve a problem for a graph with vertices compared to the time taken for a graph with vertices?

If the input size is , the time taken can be expressed as a function of . Since the time taken on different inputs of the same size can be different, the worst-case time complexity is defined to be the maximum time taken over all inputs of size . If is a polynomial in , then the algorithm is said to be a polynomial time algorithm. Cobham's thesis argues that a problem can be solved with a feasible amount of resources if it admits a polynomial-time algorithm.

Machine models and complexity measures

[edit]Turing machine

[edit]

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of a general computing machine. It is a theoretical device that manipulates symbols contained on a strip of tape. Turing machines are not intended as a practical computing technology, but rather as a general model of a computing machine—anything from an advanced supercomputer to a mathematician with a pencil and paper. It is believed that if a problem can be solved by an algorithm, there exists a Turing machine that solves the problem. Indeed, this is the statement of the Church–Turing thesis. Furthermore, it is known that everything that can be computed on other models of computation known to us today, such as a RAM machine, Conway's Game of Life, cellular automata, lambda calculus or any programming language can be computed on a Turing machine. Since Turing machines are easy to analyze mathematically, and are believed to be as powerful as any other model of computation, the Turing machine is the most commonly used model in complexity theory.

Many types of Turing machines are used to define complexity classes, such as deterministic Turing machines, probabilistic Turing machines, non-deterministic Turing machines, quantum Turing machines, symmetric Turing machines and alternating Turing machines. They are all equally powerful in principle, but when resources (such as time or space) are bounded, some of these may be more powerful than others.

A deterministic Turing machine is the most basic Turing machine, which uses a fixed set of rules to determine its future actions. A probabilistic Turing machine is a deterministic Turing machine with an extra supply of random bits. The ability to make probabilistic decisions often helps algorithms solve problems more efficiently. Algorithms that use random bits are called randomized algorithms. A non-deterministic Turing machine is a deterministic Turing machine with an added feature of non-determinism, which allows a Turing machine to have multiple possible future actions from a given state. One way to view non-determinism is that the Turing machine branches into many possible computational paths at each step, and if it solves the problem in any of these branches, it is said to have solved the problem. Clearly, this model is not meant to be a physically realizable model, it is just a theoretically interesting abstract machine that gives rise to particularly interesting complexity classes. For examples, see non-deterministic algorithm.

Other machine models

[edit]Many machine models different from the standard multi-tape Turing machines have been proposed in the literature, for example random-access machines. Perhaps surprisingly, each of these models can be converted to another without providing any extra computational power. The time and memory consumption of these alternate models may vary.[2] What all these models have in common is that the machines operate deterministically.

However, some computational problems are easier to analyze in terms of more unusual resources. For example, a non-deterministic Turing machine is a computational model that is allowed to branch out to check many different possibilities at once. The non-deterministic Turing machine has very little to do with how we physically want to compute algorithms, but its branching exactly captures many of the mathematical models we want to analyze, so that non-deterministic time is a very important resource in analyzing computational problems.

Complexity measures

[edit]For a precise definition of what it means to solve a problem using a given amount of time and space, a computational model such as the deterministic Turing machine is used. The time required by a deterministic Turing machine on input is the total number of state transitions, or steps, the machine makes before it halts and outputs the answer ("yes" or "no"). A Turing machine is said to operate within time if the time required by on each input of length is at most . A decision problem can be solved in time if there exists a Turing machine operating in time that solves the problem. Since complexity theory is interested in classifying problems based on their difficulty, one defines sets of problems based on some criteria. For instance, the set of problems solvable within time on a deterministic Turing machine is then denoted by DTIME().

Analogous definitions can be made for space requirements. Although time and space are the most well-known complexity resources, any complexity measure can be viewed as a computational resource. Complexity measures are very generally defined by the Blum complexity axioms. Other complexity measures used in complexity theory include communication complexity, circuit complexity, and decision tree complexity.

The complexity of an algorithm is often expressed using big O notation.

Best, worst and average case complexity

[edit]

The best, worst and average case complexity refer to three different ways of measuring the time complexity (or any other complexity measure) of different inputs of the same size. Since some inputs of size may be faster to solve than others, we define the following complexities:

- Best-case complexity: This is the complexity of solving the problem for the best input of size .

- Average-case complexity: This is the complexity of solving the problem on an average. This complexity is only defined with respect to a probability distribution over the inputs. For instance, if all inputs of the same size are assumed to be equally likely to appear, the average case complexity can be defined with respect to the uniform distribution over all inputs of size .

- Amortized analysis: Amortized analysis considers both the costly and less costly operations together over the whole series of operations of the algorithm.

- Worst-case complexity: This is the complexity of solving the problem for the worst input of size .

The order from cheap to costly is: Best, average (of discrete uniform distribution), amortized, worst.

For example, the deterministic sorting algorithm quicksort addresses the problem of sorting a list of integers. The worst-case is when the pivot is always the largest or smallest value in the list (so the list is never divided). In this case, the algorithm takes time O(). If we assume that all possible permutations of the input list are equally likely, the average time taken for sorting is . The best case occurs when each pivoting divides the list in half, also needing time.

Upper and lower bounds on the complexity of problems

[edit]To classify the computation time (or similar resources, such as space consumption), it is helpful to demonstrate upper and lower bounds on the maximum amount of time required by the most efficient algorithm to solve a given problem. The complexity of an algorithm is usually taken to be its worst-case complexity unless specified otherwise. Analyzing a particular algorithm falls under the field of analysis of algorithms. To show an upper bound on the time complexity of a problem, one needs to show only that there is a particular algorithm with running time at most . However, proving lower bounds is much more difficult, since lower bounds make a statement about all possible algorithms that solve a given problem. The phrase "all possible algorithms" includes not just the algorithms known today, but any algorithm that might be discovered in the future. To show a lower bound of for a problem requires showing that no algorithm can have time complexity lower than .

Upper and lower bounds are usually stated using the big O notation, which hides constant factors and smaller terms. This makes the bounds independent of the specific details of the computational model used. For instance, if , in big O notation one would write .

Complexity classes

[edit]Defining complexity classes

[edit]A complexity class is a set of problems of related complexity. Simpler complexity classes are defined by the following factors:

- The type of computational problem: The most commonly used problems are decision problems. However, complexity classes can be defined based on function problems, counting problems, optimization problems, promise problems, etc.

- The model of computation: The most common model of computation is the deterministic Turing machine, but many complexity classes are based on non-deterministic Turing machines, Boolean circuits, quantum Turing machines, monotone circuits, etc.

- The resource (or resources) that is being bounded and the bound: These two properties are usually stated together, such as "polynomial time", "logarithmic space", "constant depth", etc.

Some complexity classes have complicated definitions that do not fit into this framework. Thus, a typical complexity class has a definition like the following:

- The set of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine within time . (This complexity class is known as DTIME().)

But bounding the computation time above by some concrete function often yields complexity classes that depend on the chosen machine model. For instance, the language can be solved in linear time on a multi-tape Turing machine, but necessarily requires quadratic time in the model of single-tape Turing machines. If we allow polynomial variations in running time, Cobham-Edmonds thesis states that "the time complexities in any two reasonable and general models of computation are polynomially related" (Goldreich 2008, Chapter 1.2). This forms the basis for the complexity class P, which is the set of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine within polynomial time. The corresponding set of function problems is FP.

Important complexity classes

[edit]

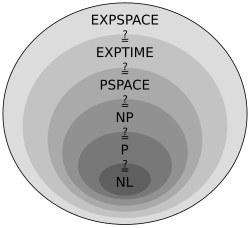

Many important complexity classes can be defined by bounding the time or space used by the algorithm. Some important complexity classes of decision problems defined in this manner are the following:

| Resource | Determinism | Complexity class | Resource constraint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space | Non-Deterministic | NSPACE() | |

| NL | |||

| NPSPACE | |||

| NEXPSPACE | |||

| Deterministic | DSPACE() | ||

| L | |||

| PSPACE | |||

| EXPSPACE | |||

| Time | Non-Deterministic | NTIME() | |

| NP | |||

| NEXPTIME | |||

| Deterministic | DTIME() | ||

| P | |||

| EXPTIME |

Logarithmic-space classes do not account for the space required to represent the problem.

It turns out that PSPACE = NPSPACE and EXPSPACE = NEXPSPACE by Savitch's theorem.

Other important complexity classes include BPP, ZPP and RP, which are defined using probabilistic Turing machines; AC and NC, which are defined using Boolean circuits; and BQP and QMA, which are defined using quantum Turing machines. #P is an important complexity class of counting problems (not decision problems). Classes like IP and AM are defined using Interactive proof systems. ALL is the class of all decision problems.

Hierarchy theorems

[edit]For the complexity classes defined in this way, it is desirable to prove that relaxing the requirements on (say) computation time indeed defines a bigger set of problems. In particular, although DTIME() is contained in DTIME(), it would be interesting to know if the inclusion is strict. For time and space requirements, the answer to such questions is given by the time and space hierarchy theorems respectively. They are called hierarchy theorems because they induce a proper hierarchy on the classes defined by constraining the respective resources. Thus there are pairs of complexity classes such that one is properly included in the other. Having deduced such proper set inclusions, we can proceed to make quantitative statements about how much more additional time or space is needed in order to increase the number of problems that can be solved.

More precisely, the time hierarchy theorem states that .

The space hierarchy theorem states that .

The time and space hierarchy theorems form the basis for most separation results of complexity classes. For instance, the time hierarchy theorem tells us that P is strictly contained in EXPTIME, and the space hierarchy theorem tells us that L is strictly contained in PSPACE.

Reduction

[edit]Many complexity classes are defined using the concept of a reduction. A reduction is a transformation of one problem into another problem. It captures the informal notion of a problem being at most as difficult as another problem. For instance, if a problem can be solved using an algorithm for , is no more difficult than , and we say that reduces to . There are many different types of reductions, based on the method of reduction, such as Cook reductions, Karp reductions and Levin reductions, and the bound on the complexity of reductions, such as polynomial-time reductions or log-space reductions.

The most commonly used reduction is a polynomial-time reduction. This means that the reduction process takes polynomial time. For example, the problem of squaring an integer can be reduced to the problem of multiplying two integers. This means an algorithm for multiplying two integers can be used to square an integer. Indeed, this can be done by giving the same input to both inputs of the multiplication algorithm. Thus we see that squaring is not more difficult than multiplication, since squaring can be reduced to multiplication.

This motivates the concept of a problem being hard for a complexity class. A problem is hard for a class of problems if every problem in can be reduced to . Thus no problem in is harder than , since an algorithm for allows us to solve any problem in . The notion of hard problems depends on the type of reduction being used. For complexity classes larger than P, polynomial-time reductions are commonly used. In particular, the set of problems that are hard for NP is the set of NP-hard problems.

If a problem is in and hard for , then is said to be complete for . This means that is the hardest problem in . (Since many problems could be equally hard, one might say that is one of the hardest problems in .) Thus the class of NP-complete problems contains the most difficult problems in NP, in the sense that they are the ones most likely not to be in P. Because the problem P = NP is not solved, being able to reduce a known NP-complete problem, , to another problem, , would indicate that there is no known polynomial-time solution for . This is because a polynomial-time solution to would yield a polynomial-time solution to . Similarly, because all NP problems can be reduced to the set, finding an NP-complete problem that can be solved in polynomial time would mean that P = NP.[3]

Important open problems

[edit]

P versus NP problem

[edit]The complexity class P is often seen as a mathematical abstraction modeling those computational tasks that admit an efficient algorithm. This hypothesis is called the Cobham–Edmonds thesis. The complexity class NP, on the other hand, contains many problems that people would like to solve efficiently, but for which no efficient algorithm is known, such as the Boolean satisfiability problem, the Hamiltonian path problem and the vertex cover problem. Since deterministic Turing machines are special non-deterministic Turing machines, it is easily observed that each problem in P is also member of the class NP.

The question of whether P equals NP is one of the most important open questions in theoretical computer science because of the wide implications of a solution.[3] If the answer is yes, many important problems can be shown to have more efficient solutions. These include various types of integer programming problems in operations research, many problems in logistics, protein structure prediction in biology,[5] and the ability to find formal proofs of pure mathematics theorems.[6] The P versus NP problem is one of the Millennium Prize Problems proposed by the Clay Mathematics Institute. There is a US$1,000,000 prize for resolving the problem.[7]

Problems in NP not known to be in P or NP-complete

[edit]It was shown by Ladner that if then there exist problems in that are neither in nor -complete.[4] Such problems are called NP-intermediate problems. The graph isomorphism problem, the discrete logarithm problem and the integer factorization problem are examples of problems believed to be NP-intermediate. They are some of the very few NP problems not known to be in or to be -complete.

The graph isomorphism problem is the computational problem of determining whether two finite graphs are isomorphic. An important unsolved problem in complexity theory is whether the graph isomorphism problem is in , -complete, or NP-intermediate. The answer is not known, but it is believed that the problem is at least not NP-complete.[8] If graph isomorphism is NP-complete, the polynomial time hierarchy collapses to its second level.[9] Since it is widely believed that the polynomial hierarchy does not collapse to any finite level, it is believed that graph isomorphism is not NP-complete. The best algorithm for this problem, due to László Babai and Eugene Luks has run time for graphs with vertices, although some recent work by Babai offers some potentially new perspectives on this.[10]

The integer factorization problem is the computational problem of determining the prime factorization of a given integer. Phrased as a decision problem, it is the problem of deciding whether the input has a prime factor less than . No efficient integer factorization algorithm is known, and this fact forms the basis of several modern cryptographic systems, such as the RSA algorithm. The integer factorization problem is in and in (and even in UP and co-UP[11]). If the problem is -complete, the polynomial time hierarchy will collapse to its first level (i.e., will equal ). The best known algorithm for integer factorization is the general number field sieve, which takes time [12] to factor an odd integer . However, the best known quantum algorithm for this problem, Shor's algorithm, does run in polynomial time. Unfortunately, this fact doesn't say much about where the problem lies with respect to non-quantum complexity classes.

Separations between other complexity classes

[edit]Many known complexity classes are suspected to be unequal, but this has not been proved. For instance , but it is possible that . If is not equal to , then is not equal to either. Since there are many known complexity classes between and , such as , , , , , , etc., it is possible that all these complexity classes collapse to one class. Proving that any of these classes are unequal would be a major breakthrough in complexity theory.

Along the same lines, is the class containing the complement problems (i.e. problems with the yes/no answers reversed) of problems. It is believed[13] that is not equal to ; however, it has not yet been proven. It is clear that if these two complexity classes are not equal then is not equal to , since . Thus if we would have whence .

Similarly, it is not known if (the set of all problems that can be solved in logarithmic space) is strictly contained in or equal to . Again, there are many complexity classes between the two, such as and , and it is not known if they are distinct or equal classes.

It is suspected that and are equal. However, it is currently open if .

Intractability

[edit]A problem that can theoretically be solved, but requires impractical and infinite resources (e.g., time) to do so, is known as an intractable problem.[14] Conversely, a problem that can be solved in practice is called a tractable problem, literally "a problem that can be handled". The term infeasible (literally "cannot be done") is sometimes used interchangeably with intractable,[15] though this risks confusion with a feasible solution in mathematical optimization.[16]

Tractable problems are frequently identified with problems that have polynomial-time solutions (, ); this is known as the Cobham–Edmonds thesis. Problems that are known to be intractable in this sense include those that are EXPTIME-hard. If is not the same as , then NP-hard problems are also intractable in this sense.

However, this identification is inexact: a polynomial-time solution with large degree or large leading coefficient grows quickly, and may be impractical for practical size problems; conversely, an exponential-time solution that grows slowly may be practical on realistic input, or a solution that takes a long time in the worst case may take a short time in most cases or the average case, and thus still be practical. Saying that a problem is not in does not imply that all large cases of the problem are hard or even that most of them are. For example, the decision problem in Presburger arithmetic has been shown not to be in , yet algorithms have been written that solve the problem in reasonable times in most cases. Similarly, algorithms can solve the NP-complete knapsack problem over a wide range of sizes in less than quadratic time and SAT solvers routinely handle large instances of the NP-complete Boolean satisfiability problem.

To see why exponential-time algorithms are generally unusable in practice, consider a program that makes operations before halting. For small , say 100, and assuming for the sake of example that the computer does operations each second, the program would run for about years, which is the same order of magnitude as the age of the universe. Even with a much faster computer, the program would only be useful for very small instances and in that sense the intractability of a problem is somewhat independent of technological progress. However, an exponential-time algorithm that takes operations is practical until gets relatively large.

Similarly, a polynomial time algorithm is not always practical. If its running time is, say, , it is unreasonable to consider it efficient and it is still useless except on small instances. Indeed, in practice even or algorithms are often impractical on realistic sizes of problems.

Continuous complexity theory

[edit]Continuous complexity theory can refer to complexity theory of problems that involve continuous functions that are approximated by discretizations, as studied in numerical analysis. One approach to complexity theory of numerical analysis[17] is information based complexity.

Continuous complexity theory can also refer to complexity theory of the use of analog computation, which uses continuous dynamical systems and differential equations.[18] Control theory can be considered a form of computation and differential equations are used in the modelling of continuous-time and hybrid discrete-continuous-time systems.[19]

History

[edit]An early example of algorithm complexity analysis is the running time analysis of the Euclidean algorithm done by Gabriel Lamé in 1844.

Before the actual research explicitly devoted to the complexity of algorithmic problems started off, numerous foundations were laid out by various researchers. Most influential among these was the definition of Turing machines by Alan Turing in 1936, which turned out to be a very robust and flexible simplification of a computer.

The beginning of systematic studies in computational complexity is attributed to the seminal 1965 paper "On the Computational Complexity of Algorithms" by Juris Hartmanis and Richard E. Stearns, which laid out the definitions of time complexity and space complexity, and proved the hierarchy theorems.[20] In addition, in 1965 Edmonds suggested to consider a "good" algorithm to be one with running time bounded by a polynomial of the input size.[21]

Earlier papers studying problems solvable by Turing machines with specific bounded resources include[20] John Myhill's definition of linear bounded automata (Myhill 1960), Raymond Smullyan's study of rudimentary sets (1961), as well as Hisao Yamada's paper[22] on real-time computations (1962). Somewhat earlier, Boris Trakhtenbrot (1956), a pioneer in the field from the USSR, studied another specific complexity measure.[23] As he remembers:

However, [my] initial interest [in automata theory] was increasingly set aside in favor of computational complexity, an exciting fusion of combinatorial methods, inherited from switching theory, with the conceptual arsenal of the theory of algorithms. These ideas had occurred to me earlier in 1955 when I coined the term "signalizing function", which is nowadays commonly known as "complexity measure".[24]

In 1967, Manuel Blum formulated a set of axioms (now known as Blum axioms) specifying desirable properties of complexity measures on the set of computable functions and proved an important result, the so-called speed-up theorem. The field began to flourish in 1971 when Stephen Cook and Leonid Levin proved the existence of practically relevant problems that are NP-complete. In 1972, Richard Karp took this idea a leap forward with his landmark paper, "Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems", in which he showed that 21 diverse combinatorial and graph theoretical problems, each infamous for its computational intractability, are NP-complete.[25]

See also

[edit]- Computational complexity

- Descriptive complexity theory

- Game complexity

- Leaf language

- Limits of computation

- List of complexity classes

- List of computability and complexity topics

- List of unsolved problems in computer science

- Parameterized complexity

- Proof complexity

- Quantum complexity theory

- Structural complexity theory

- Transcomputational problem

- Computational complexity of mathematical operations

Works on complexity

[edit]- Wuppuluri, Shyam; Doria, Francisco A., eds. (2020), Unravelling Complexity: The Life and Work of Gregory Chaitin, World Scientific, doi:10.1142/11270, ISBN 978-981-12-0006-9, S2CID 198790362

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "P vs NP Problem | Clay Mathematics Institute". www.claymath.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ See Arora & Barak 2009, Chapter 1: The computational model and why it doesn't matter

- ^ a b See Sipser 2006, Chapter 7: Time complexity

- ^ a b Ladner, Richard E. (1975), "On the structure of polynomial time reducibility", Journal of the ACM, 22 (1): 151–171, doi:10.1145/321864.321877, S2CID 14352974.

- ^ Berger, Bonnie A.; Leighton, T (1998), "Protein folding in the hydrophobic-hydrophilic (HP) model is NP-complete", Journal of Computational Biology, 5 (1): 27–40, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.139.5547, doi:10.1089/cmb.1998.5.27, PMID 9541869.

- ^ Cook, Stephen (April 2000), The P versus NP Problem (PDF), Clay Mathematics Institute, archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2010, retrieved October 18, 2006.

- ^ Jaffe, Arthur M. (2006), "The Millennium Grand Challenge in Mathematics" (PDF), Notices of the AMS, 53 (6), archived (PDF) from the original on June 12, 2006, retrieved October 18, 2006.

- ^ Arvind, Vikraman; Kurur, Piyush P. (2006), "Graph isomorphism is in SPP", Information and Computation, 204 (5): 835–852, doi:10.1016/j.ic.2006.02.002.

- ^ Schöning, Uwe (1988), "Graph Isomorphism is in the Low Hierarchy", Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 37 (3): 312–323, doi:10.1016/0022-0000(88)90010-4

- ^ Babai, László (2016). "Graph Isomorphism in Quasipolynomial Time". arXiv:1512.03547 [cs.DS].

- ^ Fortnow, Lance (September 13, 2002). "Computational Complexity Blog: Factoring". weblog.fortnow.com.

- ^ Wolfram MathWorld: Number Field Sieve

- ^ Boaz Barak's course on Computational Complexity Lecture 2

- ^ Hopcroft, J.E., Motwani, R. and Ullman, J.D. (2007) Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation, Addison Wesley, Boston/San Francisco/New York (page 368)

- ^ Meurant, Gerard (2014). Algorithms and Complexity. Elsevier. p. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-08093391-7.

- ^ Zobel, Justin (2015). Writing for Computer Science. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-44716639-9.

- ^ Smale, Steve (1997). "Complexity Theory and Numerical Analysis". Acta Numerica. 6. Cambridge Univ Press: 523–551. Bibcode:1997AcNum...6..523S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.33.4678. doi:10.1017/s0962492900002774. S2CID 5949193.

- ^ Babai, László; Campagnolo, Manuel (2009). "A Survey on Continuous Time Computations". arXiv:0907.3117 [cs.CC].

- ^ Tomlin, Claire J.; Mitchell, Ian; Bayen, Alexandre M.; Oishi, Meeko (July 2003). "Computational Techniques for the Verification of Hybrid Systems". Proceedings of the IEEE. 91 (7): 986–1001. Bibcode:2003IEEEP..91..986T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.70.4296. doi:10.1109/jproc.2003.814621.

- ^ a b Fortnow & Homer (2003)

- ^ Richard M. Karp, "Combinatorics, Complexity, and Randomness", 1985 Turing Award Lecture

- ^ Yamada, H. (1962). "Real-Time Computation and Recursive Functions Not Real-Time Computable". IEEE Transactions on Electronic Computers. EC-11 (6): 753–760. doi:10.1109/TEC.1962.5219459.

- ^ Trakhtenbrot, B.A.: Signalizing functions and tabular operators. Uchionnye Zapiski Penzenskogo Pedinstituta (Transactions of the Penza Pedagogoical Institute) 4, 75–87 (1956) (in Russian)

- ^ Boris Trakhtenbrot, "From Logic to Theoretical Computer Science – An Update". In: Pillars of Computer Science, LNCS 4800, Springer 2008.

- ^ Karp, Richard M. (1972), "Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems" (PDF), in Miller, R. E.; Thatcher, J. W. (eds.), Complexity of Computer Computations, New York: Plenum, pp. 85–103, archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2011, retrieved September 28, 2009

Textbooks

[edit]- Arora, Sanjeev; Barak, Boaz (2009), Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-42426-4, Zbl 1193.68112

- Downey, Rod; Fellows, Michael (1999), Parameterized complexity, Monographs in Computer Science, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 9780387948836

- Du, Ding-Zhu; Ko, Ker-I (2000), Theory of Computational Complexity, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-34506-0

- Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. Series of Books in the Mathematical Sciences (1st ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 9780716710455. MR 0519066. OCLC 247570676.

- Goldreich, Oded (2008), Computational Complexity: A Conceptual Perspective, Cambridge University Press

- van Leeuwen, Jan, ed. (1990), Handbook of theoretical computer science (vol. A): algorithms and complexity, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-444-88071-0

- Papadimitriou, Christos (1994), Computational Complexity (1st ed.), Addison Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-53082-7

- Sipser, Michael (2006), Introduction to the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.), USA: Thomson Course Technology, ISBN 978-0-534-95097-2

Surveys

[edit]- Khalil, Hatem; Ulery, Dana (1976), "A review of current studies on complexity of algorithms for partial differential equations", Proceedings of the annual conference on – ACM 76, pp. 197–201, doi:10.1145/800191.805573, ISBN 9781450374897, S2CID 15497394

- Cook, Stephen (1983), "An overview of computational complexity", Communications of the ACM, 26 (6): 400–408, doi:10.1145/358141.358144, ISSN 0001-0782, S2CID 14323396

- Fortnow, Lance; Homer, Steven (2003), "A Short History of Computational Complexity" (PDF), Bulletin of the EATCS, 80: 95–133

- Mertens, Stephan (2002), "Computational Complexity for Physicists", Computing in Science & Engineering, 4 (3): 31–47, arXiv:cond-mat/0012185, Bibcode:2002CSE.....4c..31M, doi:10.1109/5992.998639, ISSN 1521-9615, S2CID 633346

External links

[edit]Computational complexity theory

View on GrokipediaComputational Problems

Decision Problems

In computational complexity theory, a decision problem is formally modeled as a language over a finite alphabet , where consists of all finite strings that encode the "yes" instances of the problem, and strings not in correspond to "no" instances.[2] This representation abstracts the problem as a question with a binary outcome: given an input string , determine whether .[3] The finite alphabet typically includes symbols like for binary encodings, ensuring all inputs are finite and discrete.[4] This formulation connects directly to formal language theory, where decision problems are identified with languages, and solving the problem equates to deciding membership in .[5] In this framework, the theory originated from efforts to classify problems based on the computational resources needed to resolve language membership, building on foundational work in computability.[2] Prominent examples illustrate this concept. The Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) is the set of all Boolean formulas in conjunctive normal form for which there exists a satisfying variable assignment.[6] Graph -coloring asks whether the vertices of a given graph can be assigned at most colors such that no adjacent vertices share the same color.[7] The halting problem comprises all pairs where Turing machine halts on input .[8] Decision problems focus solely on yes/no answers, distinguishing them from search problems that require producing a solution (e.g., a satisfying assignment for SAT) or optimization problems that seek extremal values (e.g., minimum colors for graph coloring); nevertheless, search and optimization variants often reduce to decision versions via techniques like binary search on the objective.[2]Function Problems

In computational complexity theory, function problems extend the notion of decision problems by requiring the computation of an output value rather than a binary acceptance or rejection. Formally, a function problem is defined by a total function , where and are finite alphabets, and the task is to produce given an input string . This mapping from inputs to outputs captures a wide range of algorithmic tasks, such as optimization and search, where the solution must be explicitly constructed. Unlike decision problems, which only query properties of inputs, function problems emphasize the efficiency of generating results that may vary in length with the input size.[1] Prominent examples include the integer factorization problem, where the input is an integer encoded in binary and the output is a list of its prime factors in non-decreasing order. This function problem is in the class FNP, as verifying a proposed factorization can be done in polynomial time, but no polynomial-time algorithm is known for computing it, placing it outside FP under standard assumptions. Another example is the single-source shortest path problem in a weighted graph with non-negative edge weights, which computes the minimum-distance path from a source vertex to all others; this is solvable in polynomial time using algorithms like Dijkstra's, thus residing in FP. Counting problems form another key category, exemplified by #SAT, which outputs the number of satisfying truth assignments for a given Boolean formula in conjunctive normal form. The class #P, introduced by Valiant in 1979, encompasses such functions computable as the number of accepting paths in a nondeterministic polynomial-time Turing machine, with #SAT being #P-complete.[9][10][11] Function problems often relate to decision problems through corresponding search or verification tasks. For many NP decision problems, there exists a function problem counterpart in FNP that outputs a witness verifiable in polynomial time, such as producing a satisfying assignment for a satisfiable formula in SAT. However, hardness can diverge: while the decision version of integer factorization (checking for a factor in a given range) is in NP, the function version requires outputting the factors, and its presumed difficulty stems from the lack of efficient constructive methods despite efficient verification. Decision problems can be seen as special cases of function problems with binary outputs, but solving the function variant does not necessarily imply polynomial-time decidability in the reverse direction if P ≠ NP.[12] To model function computation, Turing machines are adapted with multiple tapes for clarity and efficiency in analysis. A standard formulation uses a multi-tape deterministic Turing machine with a read-only input tape holding , a write-only output tape where is inscribed upon halting, and one or more read-write work tapes for intermediate computations. The machine begins with heads positioned at the start of their respective tapes and must halt with the output tape containing exactly and the work tapes blank. Multi-tape machines simulate single-tape ones with at most a quadratic time overhead, preserving equivalence while allowing separation of input, output, and computation phases for precise resource measurement.[13]Instance Representation and Measurement

In computational complexity theory, problem instances are represented as finite strings over a finite alphabet, typically binary strings consisting of 0s and 1s, to facilitate analysis on models like Turing machines. This encoding ensures that any discrete object—such as numbers, graphs, or formulas—can be uniformly processed by a computational device. For integers, the standard binary representation is used, where the value is encoded in bits, providing a compact form that reflects the logarithmic space required. Graphs, on the other hand, are commonly encoded using an adjacency matrix, which for a graph with vertices requires bits to specify all pairwise connections, or an adjacency list that uses bits where is the number of edges.[2][14] A key requirement for these encodings is that they be "reasonable," meaning the encoding and decoding procedures must be computable in polynomial time relative to the input size, ensuring that the representation does not artificially inflate or deflate complexity measures. For instance, encoding a pair of strings can be done by concatenating them with a separator symbol (e.g., ) and then converting to binary, which is verifiable in linear time. Pathological encodings, such as unary representations for large integers where is encoded as a string of 1s (resulting in size ), are avoided because they lead to exponential growth in input length compared to the numerical value, potentially misrepresenting algorithmic efficiency.[2][15] The size of an instance, denoted , is measured as the length of its binary string encoding, which serves as the fundamental parameter for scaling resource bounds. This bit-length measure is crucial because complexity functions, such as time or space, are expressed asymptotically in terms of ; for example, an algorithm running in time for some constant is considered polynomial-time efficient only under this logarithmic-scale encoding for numerical inputs. In contrast, unary encoding would make the input size linear in the value (e.g., size for value ), turning what appears as polynomial time in unary into exponential time in binary, highlighting why binary is the default for avoiding such distortions. For graphs, the choice between adjacency matrix ( bits) and edge list ( bits) affects the effective , but both are reasonable as long as , ensuring polynomial interconvertibility.[2][14] This representation framework underpins the analysis of decision problems, where yes/no instances are encoded similarly to enable uniform complexity comparisons. By standardizing on bit-length size, the theory ensures that polynomial-time solvability corresponds to practical feasibility, independent of minor encoding variations as long as they remain polynomially equivalent.[16]Models of Computation

Turing Machines

A Turing machine (TM) is a mathematical model of computation introduced by Alan Turing to formalize the notion of algorithmic processes. It consists of an infinite tape divided into cells, each capable of holding a single symbol from a finite tape alphabet Γ, which includes a blank symbol. The machine has a finite set of states Q, a read-write head that moves left or right along the tape, and a transition function that dictates the next state, symbol to write, and head movement based on the current state and symbol read. Formally, a deterministic single-tape TM is defined as a 7-tuple , where Σ ⊆ Γ is the input alphabet, q₀ ∈ Q is the initial state, q_accept and q_reject are accepting and rejecting halting states, and the transition function is , specifying the next state, symbol to write, and head direction (left or right). The computation begins with the input string on the tape, the head at the leftmost symbol, and the machine in q₀; it halts when entering q_accept or q_reject, or if δ is undefined for the current configuration.[17] Turing machines come in variants that extend the basic model while preserving computational power. The single-tape TM uses one infinite tape for both input and working storage. In contrast, a multi-tape TM employs k ≥ 2 tapes, each with its own independent read-write head, where the transition function is , with N denoting no movement. Nondeterministic Turing machines (NTMs) generalize determinism by allowing the transition function , where denotes the power set, enabling multiple possible next configurations from any given one; an NTM accepts an input if at least one computation path reaches an accepting state. These variants were developed to model different computational paradigms, with nondeterminism first formalized for finite automata and extended to Turing machines to explore decision problems efficiently.[18] Despite structural differences, these variants are equivalent in computational capability. Any multi-tape TM can be simulated by a single-tape TM with at most a quadratic overhead in time complexity: if the multi-tape machine runs in time t(n), the single-tape simulator operates in O(t(n)^2) steps by encoding multiple tape contents onto one tape using markers and sweeping back and forth to mimic head movements. This simulation preserves the halting behavior and output, ensuring that the single-tape model suffices as the canonical reference for sequential computation. Nondeterministic TMs, while more powerful in an existential sense, can also be simulated deterministically, though with exponential time overhead in general.[19] Turing machines play a foundational role in establishing the limits of computation, particularly through the Church-Turing thesis, which posits that any function intuitively computable by a human clerk following an algorithm is computable by a Turing machine. This thesis, linking Turing's 1936 model to Alonzo Church's λ-calculus from the same year, underpins the undecidability results, such as the halting problem, by demonstrating that no TM can solve certain problems for all inputs. The thesis remains a cornerstone, justifying TMs as the standard for defining undecidable problems and the boundaries of effective computability.[17]Alternative Models

Alternative models of computation extend beyond the standard Turing machine framework, providing abstractions that facilitate the analysis of specific resource aspects like random access or parallelism while preserving computational equivalence. These models are particularly valuable for studying time and space complexities in scenarios where sequential tape access proves cumbersome. The Random Access Machine (RAM) serves as a foundational alternative, modeling a computer with an unlimited array of registers that can store integers of arbitrary size and support operations such as loading, storing, addition, subtraction, multiplication by constants, division by constants, and zero-testing.[20] In this model, the input is typically encoded as a sequence of integers on an input tape, with the word size assumed to be bits for inputs of length , enabling efficient indexing into arrays of size polynomial in .[20] RAM variants differ in their cost measures for operations. The unit-cost RAM assigns a time cost of 1 to each instruction, irrespective of operand size, which aligns well with high-level algorithm design but may overestimate efficiency for bit-level operations on large numbers.[16] In contrast, the logarithmic-cost (or log-cost) RAM charges time proportional to the bit length of the operands—specifically, for operations on integer —yielding a model closer to the bit complexity of Turing machines and avoiding artificial accelerations in arithmetic.[21] Parallel models address concurrent computation. The Parallel Random Access Machine (PRAM) extends the RAM by incorporating identical processors that operate synchronously on a shared memory, with each processor executing RAM-like instructions in lockstep.[22] Access conflicts are resolved via variants like EREW (exclusive-read, exclusive-write), where no two processors read or write the same location simultaneously; CREW (concurrent-read, exclusive-write), allowing multiple reads; or CRCW (concurrent-read, concurrent-write), with rules for write conflicts such as priority or summation.[22] Circuit families, another parallel abstraction, consist of a sequence of Boolean circuits , where has inputs and computes the function for inputs of length , using gates like AND, OR, and NOT with fan-in 2 and unbounded depth.[23] Key equivalence results link these models to Turing machines. A RAM (under logarithmic cost) simulates a multi-tape Turing machine of time complexity in time by representing tapes as arrays and using direct register access for head movements and symbol updates.[20] Conversely, a Turing machine simulates a logarithmic-cost RAM of time in time.[24] For circuits, a language belongs to P/poly if and only if it is accepted by a family of polynomial-size circuits (i.e., ), as the circuits encode polynomial-time computation with non-uniform advice.[23] Non-uniform models like circuit families exhibit limitations when analyzing space-bounded classes, such as L or NL, because their pre-wired structure bypasses the dynamic, space-constrained generation of computation steps required in uniform models; simulating space on circuits would demand nonuniformity that does not align with the tape-limited reconfiguration in Turing machines.[23]Complexity Measures

Time and Space Resources

In computational complexity theory, the primary resources measured are time and space, which quantify the computational effort required by models like Turing machines to solve problems. The input size refers to the length of the binary encoding of the input instance. The time complexity of a Turing machine is defined as the maximum number of steps takes to halt on any input of length . For deterministic Turing machines, this measures the worst-case steps across all possible computations. For nondeterministic Turing machines, the time complexity is the maximum steps over all accepting computation paths, providing a brief introduction to nondeterministic resources (with fuller details in later sections on complexity classes). Similarly, the space complexity is the maximum number of tape cells visited by during its computation on inputs of length . In the deterministic case, this captures the memory usage across the entire computation; for nondeterministic machines, it is the maximum over accepting paths. These measures define complexity classes such as , the set of languages for which there exists a deterministic Turing machine deciding in time. Analogously, uses nondeterministic machines, for deterministic space, and for nondeterministic space. A key trade-off between time and space is given by Savitch's theorem, which states that nondeterministic space can be simulated deterministically with a quadratic overhead: for space bounds .[25] This result, proved using a recursive reachability algorithm on the configuration graph of the nondeterministic machine, highlights how determinism can emulate nondeterminism at the cost of increased space.[25]Case-Based Analysis

In computational complexity theory, case-based analysis evaluates algorithmic performance by considering different scenarios of input instances, providing a more nuanced understanding than uniform measures alone. The worst-case analysis determines the maximum resource usage, such as time or space, over all possible inputs of a given size , offering a guarantee on the upper bound for the algorithm's behavior in the most adverse conditions. This approach is foundational for defining complexity classes like P, where an algorithm is deemed polynomial-time if its worst-case running time is bounded by a polynomial in .[26] The best-case analysis, in contrast, examines the minimum resource usage over all inputs of size , highlighting the algorithm's efficiency under ideal conditions. For instance, in linear search, the best case occurs when the target element is at the first position, requiring only a constant number of operations, . While informative for understanding potential optimizations, best-case analysis is less emphasized in complexity theory because it does not capture typical or guaranteed performance, often serving more as a theoretical lower bound rather than a practical predictor. Average-case analysis addresses the expected resource usage under a specified probability distribution over inputs, aiming to model real-world scenarios more realistically. Leonid Levin pioneered this framework in the 1980s by introducing distributional problems—pairs of a language and a sequence of probability ensembles—and defining average polynomial-time as the existence of a polynomial-time algorithm whose expected running time is polynomial with respect to the distribution. This theory enables the study of average-case completeness, analogous to worst-case NP-completeness, and has been extended to show reductions between distributional problems in NP.[27] However, average-case analysis has notable limitations. It inherently depends on the choice of probability distribution, which may not accurately represent natural input instances, leading to debates over "reasonable" distributions. Additionally, issues with pseudorandomness arise, as derandomizing average-case assumptions often requires hardness against pseudorandom generators, complicating connections to worst-case complexity and potentially undermining the robustness of results if the distribution is indistinguishable from random but hard to analyze. These challenges highlight why worst-case remains the standard for formal complexity classes, while average-case informs practical algorithm design.[28]Upper and Lower Bounds

In computational complexity theory, upper bounds on the resources required to solve a problem are established constructively by designing algorithms that achieve a specified performance guarantee, typically in terms of time or space complexity. For instance, the merge sort algorithm sorts elements in time in the comparison model, where each comparison reveals one bit of information about the input order. This bound is tight in the worst case for comparison-based sorting, as demonstrated by matching lower bounds derived from information theory.[29] Lower bounds, in contrast, provide proofs of impossibility, showing that no algorithm can perform better than a certain threshold on a given computational model. A fundamental technique for establishing such bounds is diagonalization, which constructs a problem instance that differs from all potential solutions within a restricted resource class, ensuring separation between complexity levels. The time hierarchy theorem exemplifies this approach: for any time-constructible function where is at least linear, there exists a language decidable in time but not in time on a deterministic Turing machine. This theorem implies strict separations in the time complexity hierarchy, such as DTIME DTIME.[30][31] Another powerful method for lower bounds is communication complexity, which analyzes the minimum information exchange needed between parties to compute a function, often yielding separations in models like circuits or streaming algorithms. For example, the parity function, which computes the XOR of bits, requires time in the deterministic Turing machine model because any algorithm must examine all input bits to determine the output correctly. In the constant-depth circuit model (AC), parity cannot be computed at all, as proven using the switching lemma, which shows that random restrictions simplify such circuits to constant size while preserving the function's hardness. A classic information-theoretic lower bound applies to comparison-based sorting: any such algorithm requires at least comparisons in the worst case, since there are possible permutations and each comparison branches the decision tree by at most a factor of 2.[32][33] Proving strong lower bounds, particularly for separating P from NP, faces significant barriers. The relativization barrier, introduced by Baker, Gill, and Solovay, demonstrates that there exist oracles and such that and , implying that any proof technique relativizing to oracles (including many diagonalization arguments) cannot resolve the P vs. NP question. Similarly, the natural proofs barrier by Razborov and Rudich shows that most known lower bound techniques for explicit Boolean functions are "natural" proofs—combining largeness (distinguishing hard functions), constructivity (efficient computability), and usefulness (applying to pseudorandom generators)—but such proofs would imply the existence of efficient pseudorandom generators against P/poly if one-way functions exist, contradicting cryptographic assumptions. These barriers highlight why general lower bounds remain challenging, directing research toward non-relativizing or non-natural proof methods.[34]Complexity Classes

Definitions and Basic Classes

In computational complexity theory, a complexity class is a set of decision problems, formalized as languages over a finite alphabet, that can be decided by a computational model—typically a Turing machine—within specified bounds on resources such as time or space. These classes provide a framework for classifying problems according to their inherent computational difficulty, focusing on asymptotic resource requirements as input size grows.[35] The class P (polynomial time) consists of all languages that can be decided by a deterministic Turing machine in time polynomial in the input length n. Formally, where denotes the set of languages decidable in time on a deterministic Turing machine. Problems in P are considered "efficiently solvable" or tractable, as polynomial time aligns with feasible computation for practical input sizes. A prominent example is the primality testing problem: given an integer n, determine if it is prime. This was shown to be in P by the AKS algorithm, a deterministic procedure running in time .[36] The class NP (nondeterministic polynomial time) includes all languages for which a "yes" instance has a polynomial-length certificate verifiable in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine, or equivalently, languages decidable in polynomial time by a nondeterministic Turing machine. This captures problems where solutions can be checked efficiently, even if finding them is hard. Formally, with defined analogously for nondeterministic machines. A classic example is the circuit satisfiability problem: given a Boolean circuit, does there exist an input assignment that makes the output true? A proposed satisfying assignment serves as a certificate verifiable by evaluating the circuit in linear time relative to its size.[37][38] The class co-NP comprises the complements of languages in NP; that is, for a language , its complement is in co-NP. Thus, co-NP problems are those where "no" instances have polynomial-time verifiable certificates. If , then co-NP would equal NP, but this remains an open question. Examples include tautology verification for Boolean formulas, the complement of circuit satisfiability.[35]Advanced Classes and Hierarchies

Beyond the basic polynomial-time classes such as P and NP, computational complexity theory defines higher-level classes that capture exponential resource bounds, forming layered structures with proven separations. The class EXP consists of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine in time bounded by , where is the input length.[19] Similarly, NEXP includes problems solvable by a nondeterministic Turing machine in exponential time, defined as the union over constants of NTIME().[39] These classes extend the polynomial framework to superpolynomial resources, with NEXP properly containing NP, as proven by the nondeterministic time hierarchy theorem. The class PSPACE encompasses problems decidable using polynomial space on a deterministic Turing machine, equivalent to NPSPACE by Savitch's theorem, which shows that nondeterministic polynomial space can be simulated deterministically with quadratic space overhead. Hierarchy theorems establish strict inclusions among these classes by demonstrating that increased computational resources enable solving strictly more problems. The deterministic time hierarchy theorem states that if and are time-constructible functions with , then DTIME() is properly contained in DTIME().[19] This implies, for example, that P is strictly contained in EXP, as the time functions and satisfy the conditions. A nondeterministic version extends this to NTIME, separating NP from NEXP. The space hierarchy theorem provides an analogous result: for space-constructible and with , SPACE() SPACE().[40] Consequently, L PSPACE EXPSPACE, highlighting how space bounds create distinct computational powers without the logarithmic factor required in time hierarchies. The polynomial hierarchy (PH) builds a infinite tower of classes above P and NP using alternating existential and universal quantifiers over polynomial-time predicates. It is defined inductively: , and for , consists of languages where membership is witnessed by a polynomial-time verifier with alternating quantifiers starting with existential, starts with universal, and .[41] NP corresponds to and coNP to , with the full PH as the union over all . If for some , the hierarchy collapses to that level, but no such collapse is known, preserving the suspected strict inclusions . Oracle separations reveal the limitations of relativizing techniques in proving inclusions like P versus NP. There exists an oracle such that , where superscript denotes oracle access, showing that some proof strategies fail relative to .[42] Conversely, an oracle exists where , indicating that relativization alone cannot resolve the P versus NP question, as any proof must transcend oracle models to distinguish these cases.[42] These results underscore the nuanced structure of complexity classes beyond absolute separations.Reductions and Completeness

In computational complexity theory, reductions provide a formal method to compare the relative hardness of decision problems by transforming instances of one problem into instances of another while preserving the yes/no answer. A many-one reduction, also known as a Karp reduction, from problem to problem is a polynomial-time computable function such that for any input , is a yes-instance of if and only if is a yes-instance of [7]. This ensures that if can be solved efficiently, so can , as the transformation and solution of the reduced instance can be done in polynomial time. In contrast, a Turing reduction, or Cook reduction, allows a polynomial-time algorithm for to query an oracle for multiple times, potentially adaptively, to determine the answer for [6]. Turing reductions are more powerful than many-one reductions, as they permit interactive use of the oracle, but both are used to establish hardness relationships within polynomial-time bounded computations. The concept of completeness builds on reductions to identify the hardest problems in a complexity class. A problem is complete for a class (e.g., NP) via polynomial-time reductions if (1) and (2) every problem in reduces to under the chosen reduction type. For NP, completeness is defined using polynomial-time many-one reductions. The foundational result is the Cook-Levin theorem, which proves that the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT)—determining if there exists an assignment of truth values to variables that makes a given Boolean formula true—is NP-complete under polynomial-time many-one reductions.[6] The proof reduces any language in NP to SAT via a polynomial-time many-one reduction by constructing a Boolean formula that is satisfiable if and only if the nondeterministic verifier accepts the input. The formula encodes possible computation paths of the verifier. Subsequent work established many-one reductions from SAT to other problems, yielding additional NP-complete problems. For instance, 3-SAT, the restriction of SAT to formulas in conjunctive normal form with exactly three literals per clause, is NP-complete via a polynomial-time many-one reduction from general SAT that introduces auxiliary variables to handle clauses of other sizes[6]. Similarly, the Clique problem—deciding if a graph contains a clique of size at least —and the Vertex Cover problem—deciding if a graph has a vertex cover of size at most —are NP-complete via polynomial-time many-one reductions from 3-SAT, as detailed in Karp's classification of 21 NP-complete problems[7]. These reductions transform logical clauses into graph structures, such as gadgets representing variable assignments or clause implications, preserving satisfiability. While complete problems capture the hardest cases in NP, not all problems in NP fall into P or the complete ones, assuming P ≠ NP. Ladner's theorem demonstrates the existence of NP-intermediate problems—those in NP but neither in P nor NP-complete under polynomial-time many-one reductions—by constructing a hierarchy of problems with varying densities of yes-instances, using diagonalization over the complete problems[43]. This result highlights the rich structure within NP and motivates the study of problem hierarchies beyond completeness. Reductions also propagate membership in complexity classes: if reduces to via a polynomial-time reduction and , then , since the reduction combined with a polynomial-time algorithm for yields one for [7]. Conversely, if is NP-hard (every NP problem reduces to ) and , then . This transitivity underpins the power of reductions in classifying problem difficulty.Open Questions

P versus NP

The P versus NP problem is the fundamental question in computational complexity theory of whether the complexity class P equals the class NP, where P consists of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time, and NP consists of decision problems verifiable by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time given a suitable certificate. Equivalently, it asks whether every problem for which a proposed solution can be checked efficiently can also be solved efficiently. This formulation captures the distinction between search (finding solutions) and verification (checking solutions), as problems in NP have short proofs of membership that can be verified quickly, but finding such proofs may be hard.[44][45] If P = NP, the implications would be profound across computer science and beyond. In cryptography, the collapse would render many public-key systems insecure, as they depend on the computational hardness of NP problems like integer factorization or the discrete logarithm problem, which would become solvable in polynomial time. Similarly, optimization would undergo a revolution, enabling efficient algorithms for NP-hard problems such as the traveling salesman problem or graph coloring, transforming fields like logistics, scheduling, and operations research by making intractable global optima computable. Conversely, proving P ≠ NP would confirm the inherent difficulty of certain problems, justifying approximations and heuristics in practice.[46][45] Partial results provide indirect evidence and conditional separations but no unconditional resolution. It is known that P = NP implies the non-existence of one-way functions, which are efficiently computable functions that are hard to invert on a significant fraction of inputs; since one-way functions underpin modern cryptography and are widely believed to exist, their presumed existence supports P ≠ NP, though unconditionally proving their existence remains open. Another open question is whether NP ⊆ BPP, where BPP is the class of problems solvable by a probabilistic Turing machine in polynomial time with bounded error; resolving this affirmatively would place NP problems in randomized polynomial time but is considered unlikely without collapsing other complexity hierarchies.[47][45][46] The problem's status as one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems, established by the Clay Mathematics Institute in 2000, underscores its importance, offering a $1,000,000 prize for a correct solution. Significant barriers hinder progress, notably the Baker–Gill–Solovay theorem, which demonstrates that relativization techniques—proofs that hold relative to any oracle—are insufficient to separate P and NP, as there exist oracles where and oracles where . This relativization barrier implies that any resolution must exploit non-relativizing properties of computation, such as arithmetization or interactive proofs.[44][42]Intermediate Problems and Class Separations

In computational complexity theory, intermediate problems are those in NP that are neither in P nor NP-complete, assuming P ≠ NP. Ladner's theorem establishes the existence of such problems by constructing a language in NP that is reducible to an NP-complete problem like SAT but avoids both P and NP-completeness through a diagonalization argument that "punches holes" in the complete problem. A prominent candidate for an NP-intermediate problem was the graph isomorphism problem, which asks whether two given graphs are isomorphic; it was long suspected to be intermediate until László Babai developed a quasi-polynomial time algorithm in 2015, placing it in \tilde{O}(n^{\mathrm{polylog} n}), though this remains slower than polynomial time and does not resolve its status relative to P.[48] Other natural candidates include integer factorization, which decides whether a given integer has a factor in a specified range, and the discrete logarithm problem, which determines if a logarithm exists in a finite field; both are in NP ∩ co-NP due to efficient verifiability of solutions and their complements, making NP-completeness unlikely, and they are widely believed to be intermediate as no polynomial-time algorithm is known despite extensive study in cryptography. Regarding class separations, a key result equates interactive proofs with polynomial space: the class IP, consisting of languages with polynomial-time probabilistic verifiers interacting with unbounded provers, equals PSPACE, as shown by Shamir building on earlier work by Lund, Fortnow, Karloff, and Nisan that placed the polynomial hierarchy PH inside IP. Whether PH is a proper subset of PSPACE remains open, with relativized separations existing relative to random oracles but no unconditional proof. Hierarchy theorems provide separations between time and space classes; the time hierarchy theorem shows that TIME(n) \subsetneq TIME(n^2), implying strict separations like DTIME(n) \subsetneq DTIME(n \log n), while the space hierarchy theorem yields DSPACE(n) \subsetneq DSPACE(n^2), demonstrating that more space solves strictly more problems. As of 2025, no major collapses have occurred among these classes, though derandomization efforts continue to make progress toward placing BPP, the class of problems solvable in polynomial time with bounded error probability, inside P; recent advances include improved pseudorandom generators under hardness assumptions, but unconditional derandomization of BPP remains elusive.[49]Intractability and Practical Implications

NP-Completeness and Hardness

NP-completeness identifies the hardest problems within the class NP, meaning that if any NP-complete problem admits a polynomial-time algorithm, then every problem in NP can be solved in polynomial time, collapsing the distinction between verification and search in nondeterministic polynomial time. This equivalence arises because NP-complete problems are interreducible via polynomial-time reductions, so solving one efficiently allows transforming and solving all others in NP. The concept was introduced by showing that the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) is NP-complete, establishing a benchmark for hardness in combinatorial optimization.[6] Beyond NP, analogous notions of completeness exist for higher complexity classes, capturing problems believed to require substantially more resources. In PSPACE, the class of problems solvable in polynomial space, the quantified Boolean formulas (QBF) problem is PSPACE-complete; QBF extends SAT by allowing alternating existential and universal quantifiers over Boolean variables, modeling more expressive logical queries that demand exponential exploration in the worst case.[50] Similarly, in EXP (deterministic exponential time), the problem of determining the winner in generalized chess on an n × n board—where queens can move any distance and the game follows standard rules otherwise—is EXP-complete, highlighting the vast search spaces in strategic games with unbounded board sizes. To address intractability when certain parameters remain small, parameterized complexity theory distinguishes fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) problems, solvable in time f(k) · n^c where k is the parameter, n the input size, f arbitrary, and c constant, from those that are W[51]-hard, presumed not FPT under standard conjectures. This framework reveals tractable cases for NP-hard problems; for instance, vertex cover is FPT when parameterized by solution size k, admitting a 2^k · n algorithm, while the clique problem is W[51]-complete, resisting such efficiency even for small cliques.[52] NP-hard problems pervade practical applications due to their modeling power for combinatorial decisions under constraints, often leading to exponential blowups in real scenarios. In artificial intelligence, classical planning—formulated as finding a sequence of actions to reach a goal state in a propositional domain without delete effects—is NP-complete, as it reduces to SAT for verifying plan existence, capturing the challenge of goal-directed reasoning in automated systems. In logistics, the traveling salesman problem (TSP), which seeks the shortest tour visiting a set of cities, is NP-hard, modeling route optimization where the number of possible paths grows factorially with cities, complicating supply chain and delivery scheduling.[7]Coping with Intractable Problems