Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Consensus decision-making

View on Wikipedia

Consensus decision-making is a group decision-making process in which participants work together to develop proposals for actions that achieve a broad acceptance. Consensus is reached when everyone in the group assents to a decision (or almost everyone; see stand aside) even if some do not fully agree to or support all aspects of it. It differs from simple unanimity, which requires all participants to support a decision. Consensus decision-making in a democracy is consensus democracy.[1]

Origin and meaning of term

[edit]The word consensus is Latin meaning "agreement, accord", derived from consentire meaning "feel together".[2] A noun, consensus can represent a generally accepted opinion[3] – "general agreement or concord; harmony", "a majority of opinion"[4] – or the outcome of a consensus decision-making process. This article refers to the process and the outcome (e.g. "to decide by consensus" and "a consensus was reached").

History

[edit]Consensus decision-making, as a self-described practice, originates from several nonviolent, direct action groups that were active in the Civil rights, Peace and Women's movements in the USA during counterculture of the 1960s. The practice gained popularity in the 1970s through the anti-nuclear movement, and peaked in popularity in the early 1980s.[5] Consensus spread abroad through the anti-globalization and climate movements, and has become normalized in anti-authoritarian spheres in conjunction with affinity groups and ideas of participatory democracy and prefigurative politics.[6]

The Movement for a New Society (MNS) has been credited for popularizing consensus decision-making.[7][6] Unhappy with the inactivity of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) against the Vietnam War, Lawrence Scott started A Quaker Action Group (AQAG) in 1966 to try and encourage activism within the Quakers. By 1971 AQAG members felt they needed not only to end the war, but transform civil society as a whole, and renamed AQAG to MNS. MNS members used consensus decision-making from the beginning as an adaptation of the Quaker decision-making they were used to. MNS trained the anti-nuclear Clamshell Alliance (1976)[8][9] and Abalone Alliance (1977) to use consensus, and in 1977 published Resource Manual for a Living Revolution,[10] which included a section on consensus.

An earlier account of consensus decision-making comes from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee[11] (SNCC), the main student organization of the civil rights movement, founded in 1960. Early SNCC member Mary King, later reflected: "we tried to make all decisions by consensus ... it meant discussing a matter and reformulating it until no objections remained".[12] This way of working was brought to the SNCC at its formation by the Nashville student group, who had received nonviolence training from James Lawson and Myles Horton at the Highlander Folk School.[11] However, as the SNCC faced growing internal and external pressure toward the mid-1960s, it developed into a more hierarchical structure, eventually abandoning consensus.[13]

Women Strike for Peace (WSP) are also accounted as independently used consensus from their founding in 1961. Eleanor Garst (herself influenced by Quakers) introduced the practice as part of the loose and participatory structure of WSP.[14]

As consensus grew in popularity, it became less clear who influenced who. Food Not Bombs, which started in 1980 in connection with an occupation of Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant organized by the Clamshell Alliance, adopted consensus for their organization.[15] Consensus was used in the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, which inspired the S11 (World Economic Forum protest) in 2000 to do so too.[16] Consensus was used at the first Camp for Climate Action (2006) and subsequent camps. Occupy Wall Street (2011) made use of consensus in combination with techniques such as the people's microphone and hand signals.

Objectives

[edit]Characteristics of consensus decision-making include:

- Collaboration: Participants contribute to a shared proposal and shape it into a decision that meets the concerns of all group members as much as possible.[17]

- Cooperation: Participants in an effective consensus process should strive to reach the best possible decision for the group and all of its members, rather than competing for personal preferences.

- Egalitarianism: All members of a consensus decision-making body should be afforded, as much as possible, equal input into the process. All members have the opportunity to present and amend proposals.

- Inclusion: As many stakeholders as possible should be involved in a consensus decision-making process.

- Participation: The consensus process should actively solicit the input and participation of all decision-makers.[18]

Alternative to common decision-making practices

[edit]Consensus decision-making is an alternative to commonly practiced group decision-making processes.[19] Robert's Rules of Order, for instance, is a guide book used by many organizations. This book on Parliamentary Procedure allows the structuring of debate and passage of proposals that can be approved through a form of majority vote. It does not emphasize the goal of full agreement. Critics of such a process believe that it can involve adversarial debate and the formation of competing factions. These dynamics may harm group member relationships and undermine the ability of a group to cooperatively implement a contentious decision. Consensus decision-making attempts to address the beliefs of such problems. Proponents claim that outcomes of the consensus process include:[17][20]

- Better decisions: Through including the input of all stakeholders the resulting proposals may better address all potential concerns.

- Better implementation: A process that includes and respects all parties, and generates as much agreement as possible sets the stage for greater cooperation in implementing the resulting decisions.

- Better group relationships: A cooperative, collaborative group atmosphere can foster greater group cohesion and interpersonal connection.

Decision rules

[edit]Consensus is not synonymous with unanimity – though that may be a rule agreed to in a specific decision-making process. The level of agreement necessary to finalize a decision is known as a decision rule.[17][21]

Diversity of opinion is normal in most all situations, and will be represented proportionately in an appropriately functioning group.

Even with goodwill and social awareness, citizens are likely to disagree in their political opinions and judgments. Differences of interest as well as of perception and values will lead the citizens to divergent views about how to direct and use the organized political power of the community, in order to promote and protect common interests. If political representatives reflect this diversity, then there will be as much disagreement in the legislature as there is in the population.[22]

Blocking and other forms of dissent

[edit]To ensure the agreement or consent of all participants is valued, many groups choose unanimity or near-unanimity as their decision rule. Groups that require unanimity allow individual participants the option of blocking a group decision. This provision motivates a group to make sure that all group members consent to any new proposal before it is adopted. When there is potential for a block to a group decision, both the group and dissenters in the group are encouraged to collaborate until agreement can be reached. Simply vetoing a decision is not considered a responsible use of consensus blocking. Some common guidelines for the use of consensus blocking include:[17][23]

- Providing an option for those who do not support a proposal to "stand aside" rather than block.

- Requiring a block from two or more people to put a proposal aside.

- Requiring the blocking party to supply an alternative proposal or a process for generating one.[24]

- Limiting each person's option to block consensus to a handful of times in one's life.

- Limiting the option of blocking to decisions that are substantial to the mission or operation of the group and not allowing blocking on routine decisions.

- Limiting the allowable rationale for blocking to issues that are fundamental to the group's mission or potentially disastrous to the group.

Dissent options

[edit]A participant who does not support a proposal may have alternatives to simply blocking it. Some common options may include the ability to:

- Declare reservations: Group members who are willing to let a motion pass but desire to register their concerns with the group may choose "declare reservations." If there are significant reservations about a motion, the decision-making body may choose to modify or re-word the proposal.[25]

- Stand aside: A "stand aside" may be registered by a group member who has a "serious personal disagreement" with a proposal, but is willing to let the motion pass. Although stand asides do not halt a motion, it is often regarded as a strong "nay vote" and the concerns of group members standing aside are usually addressed by modifications to the proposal. Stand asides may also be registered by users who feel they are incapable of adequately understanding or participating in the proposal.[26][27][28]

- Object: Any group member may "object" to a proposal. In groups with a unanimity decision rule, a single block is sufficient to stop a proposal. Other decision rules may require more than one objection for a proposal to be blocked or not pass (see previous section, § Decision rules).

Process models

[edit]The basic model for achieving consensus as defined by any decision rule involves:

- Collaboratively generating a proposal

- Identifying unsatisfied concerns

- Modifying the proposal to generate as much agreement as possible

All attempts at achieving consensus begin with a good faith attempt at generating full-agreement, regardless of decision rule threshold.

Spokescouncil

[edit]In the spokescouncil model, affinity groups make joint decisions by each designating a speaker and sitting behind that circle of spokespeople, akin to the spokes of a wheel. While speaking rights might be limited to each group's designee, the meeting may allot breakout time for the constituent groups to discuss an issue and return to the circle via their spokesperson. In the case of an activist spokescouncil preparing for the A16 Washington D.C. protests in 2000, affinity groups disputed their spokescouncil's imposition of nonviolence in their action guidelines. They received the reprieve of letting groups self-organize their protests, and as the city's protest was subsequently divided into pie slices, each blockaded by an affinity group's choice of protest. Many of the participants learned about the spokescouncil model on the fly by participating in it directly, and came to better understand their planned action by hearing others' concerns and voicing their own.[29]

Modified Borda Count vote

[edit]In Designing an All-Inclusive Democracy (2007), Emerson proposes a consensus oriented approach based on the Modified Borda Count (MBC) voting method. The group first elects, say, three referees or consensors. The debate on the chosen problem is initiated by the facilitator calling for proposals. Every proposed option is accepted if the referees decide it is relevant and conforms with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The referees produce and display a list of these options. The debate proceeds, with queries, comments, criticisms and/or even new options. If the debate fails to come to a verbal consensus, the referees draw up a final list of options - usually between 4 and 6 - to represent the debate. When all agree, the chair calls for a preferential vote, as per the rules for a Modified Borda Count. The referees decide which option, or which composite of the two leading options, is the outcome. If its level of support surpasses a minimum consensus coefficient, it may be adopted.[30][31]

Blocking

[edit]

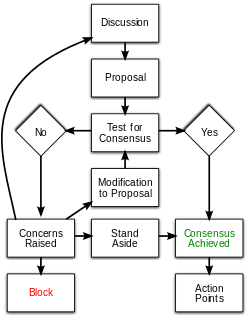

Groups that require unanimity commonly use a core set of procedures depicted in this flow chart.[32][33][34]

Once an agenda for discussion has been set and, optionally, the ground rules for the meeting have been agreed upon, each item of the agenda is addressed in turn. Typically, each decision arising from an agenda item follows through a simple structure:

- Discussion of the item: The item is discussed with the goal of identifying opinions and information on the topic at hand. The general direction of the group and potential proposals for action are often identified during the discussion.

- Formation of a proposal: Based on the discussion a formal decision proposal on the issue is presented to the group.

- Call for consensus: The facilitator of the decision-making body calls for consensus on the proposal. Each member of the group usually must actively state whether they agree or consent, stand aside, or object, often by using a hand gesture or raising a colored card, to avoid the group interpreting silence or inaction as agreement. The number of objections is counted to determine if this step's consent threshold is satisfied. If it is, dissenters are asked to share their concerns with proceeding with the agreement, so that any potential harms can be addressed/minimized. This can happen even if the consent threshold is unanimity, especially if many voters stand aside.

- Identification and addressing of concerns: If consensus is not achieved, each dissenter presents his or her concerns on the proposal, potentially starting another round of discussion to address or clarify the concern.

- Modification of the proposal: The proposal is amended, re-phrased or ridered in an attempt to address the concerns of the decision-makers. The process then returns to the call for consensus and the cycle is repeated until a satisfactory decision passes the consent threshold for the group.

Quaker-based model

[edit]Quaker-based consensus[35] is said to be effective because it puts in place a simple, time-tested structure that moves a group towards unity. The Quaker model is intended to allow hearing individual voices while providing a mechanism for dealing with disagreements.[20][36][37]

The Quaker model has been adapted by Earlham College for application to secular settings, and can be effectively applied in any consensus decision-making process.

Its process includes:

- Multiple concerns and information are shared until the sense of the group is clear.

- Discussion involves active listening and sharing information.

- Norms limit number of times one asks to speak to ensure that each speaker is fully heard.

- Ideas and solutions belong to the group; no names are recorded.

- Ideally, differences are resolved by discussion. The facilitator ("clerk" or "convenor" in the Quaker model) identifies areas of agreement and names disagreements to push discussion deeper.

- The facilitator articulates the sense of the discussion, asks if there are other concerns, and proposes a "minute" of the decision.

- The group as a whole is responsible for the decision and the decision belongs to the group.

- The facilitator can discern if one who is not uniting with the decision is acting without concern for the group or in selfish interest.

- Ideally, all dissenters' perspectives are synthesized into the final outcome for a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.[35]

- Should some dissenter's perspective not harmonize with the others, that dissenter may "stand aside" to allow the group to proceed, or may opt to "block". "Standing aside" implies a certain form of silent consent. Some groups allow "blocking" by even a single individual to halt or postpone the entire process.[20]

Key components of Quaker-based consensus include a belief in a common humanity and the ability to decide together. The goal is "unity, not unanimity." Ensuring that group members speak only once until others are heard encourages a diversity of thought. The facilitator is understood as serving the group rather than acting as person-in-charge.[38] In the Quaker model, as with other consensus decision-making processes, articulating the emerging consensus allows members to be clear on the decision in front of them. As members' views are taken into account they are likely to support it.[39]

Roles

[edit]The consensus decision-making process often has several roles designed to make the process run more effectively. Although the name and nature of these roles varies from group to group, the most common are the facilitator, consensor, a timekeeper, an empath and a secretary or notes taker. Not all decision-making bodies use all of these roles, although the facilitator position is almost always filled, and some groups use supplementary roles, such as a Devil's advocate or greeter. Some decision-making bodies rotate these roles through the group members in order to build the experience and skills of the participants, and prevent any perceived concentration of power.[40]

The common roles in a consensus meeting are:

- Facilitator: As the name implies, the role of the facilitator is to help make the process of reaching a consensus decision easier. Facilitators accept responsibility for moving through the agenda on time; ensuring the group adheres to the mutually agreed-upon mechanics of the consensus process; and, if necessary, suggesting alternate or additional discussion or decision-making techniques, such as go-arounds, break-out groups or role-playing.[41][42] Some consensus groups use two co-facilitators. Shared facilitation is often adopted to diffuse the perceived power of the facilitator and create a system whereby a co-facilitator can pass off facilitation duties if he or she becomes more personally engaged in a debate.[43]

- Consensor: The team of consensors is responsible for accepting those relevant proposals; for displaying an initial list of these options; for drawing up a balanced list of options to represent the entire debate; to analyse the preferences cast in any subsequent ballot; and, if need be, to determine the composite decision from the two most popular options.

- Timekeeper: The purpose of the timekeeper is to ensure the decision-making body keeps to the schedule set in the agenda. Effective timekeepers use a variety of techniques to ensure the meeting runs on time including: giving frequent time updates, ample warning of short time, and keeping individual speakers from taking an excessive amount of time.[40]

- Empath or vibe watch: The empath, or 'vibe watch' as the position is sometimes called, is charged with monitoring the 'emotional climate' of the meeting, taking note of the body language and other non-verbal cues of the participants. Defusing potential emotional conflicts, maintaining a climate free of intimidation and being aware of potentially destructive power dynamics, such as sexism or racism within the decision-making body, are the primary responsibilities of the empath.[41]

- Note taker: The role of the notes taker or secretary is to document the decisions, discussion and action points of the decision-making body.

Tools and methods

[edit]

- Some consensus decision-making bodies use a system of colored cards to indicate speaker priority. For instance, red cards to indicate feedback on a breach in rules or decorum, yellow cards for clarifying questions, and green cards for desire to speak.[24]

- Hand signals are another method for reading a room's positions nonverbally. They work well with groups of fewer than 250 people and especially with multi-lingual groups.[44] The nature and meaning of individual gestures varies between groups, but a widely adopted core set of hand signals include: wiggling of the fingers on both hands, a gesture sometimes referred to as "twinkling", to indicate agreement; raising a fist or crossing both forearms with hands in fists to indicate a block or strong disagreement; and making a "T" shape with both hands, the "time out" gesture, to call attention to a point of process or order.[45][46] One common set of hand signals is called the "Fist-to-Five" or "Fist-of-Five". In this method each member of the group can hold up a fist to indicate blocking consensus, one finger to suggest changes, two fingers to discuss minor issues, three fingers to indicate willingness to let issue pass without further discussion, four fingers to affirm the decision as a good idea, and five fingers to volunteer to take a lead in implementing the decision.[47] A similar set of hand signals are used by the Occupy Wall Street protesters in their group negotiations.[48]

- First-past-the-post is used as a fall-back method when consensus cannot be reached within a given time frame.[49] If the potential outcome of the fall-back method can be anticipated, then those who support that outcome have incentives to block consensus so that the fall-back method gets applied. Special fall-back methods have been developed that reduce this incentive.[50]

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of blocking

[edit]Critics of consensus blocking often observe that the option, while potentially effective for small groups of motivated or trained individuals with a sufficiently high degree of affinity, has a number of possible shortcomings, notably

- Preservation of the status quo: In decision-making bodies that use formal consensus, the ability of individuals or small minorities to block agreement gives an enormous advantage to anyone who supports the existing state of affairs. This can mean that a specific state of affairs can continue to exist in an organization long after a majority of members would like it to change.[51]

- Susceptibility to widespread disagreement: Giving the right to block proposals to all group members may result in the group becoming hostage to an inflexible minority or individual. When a popular proposal is blocked the group actually experiences widespread disagreement, the opposite of the consensus process's goal. Furthermore, "opposing such obstructive behavior [can be] construed as an attack on freedom of speech and in turn [harden] resolve on the part of the individual to defend his or her position."[52] As a result, consensus decision-making has the potential to reward the least accommodating group members while punishing the most accommodating.

- Stagnation and group dysfunction: When groups cannot make the decisions necessary to function (because they cannot resolve blocks), they may lose effectiveness in accomplishing their mission.

- Susceptibility to splitting and excluding members: When high levels of group member frustration result from blocked decisions or inordinately long meetings, members may leave the group, try to get to others to leave, or limit who has entry to the group.

- Channeling decisions away from an inclusive group process: When group members view the status quo as unjustly difficult to change through a whole group process, they may begin to delegate decision-making to smaller committees or to an executive committee. In some cases members begin to act unilaterally because they are frustrated with a stagnated group process.

Groupthink

[edit]Consensus seeks to improve solidarity in the long run. Accordingly, it should not be confused with unanimity in the immediate situation, which is often a symptom of groupthink. Studies of effective consensus process usually indicate a shunning of unanimity or "illusion of unanimity"[53] that does not hold up as a group comes under real-world pressure (when dissent reappears). Cory Doctorow, Ralph Nader and other proponents of deliberative democracy or judicial-like methods view explicit dissent as a symbol of strength.

In his book about Wikipedia, Joseph Reagle considers the merits and challenges of consensus in open and online communities.[54] Randy Schutt,[55] Starhawk[56] and other practitioners of direct action focus on the hazards of apparent agreement followed by action in which group splits become dangerously obvious.

Unanimous, or apparently unanimous, decisions can have drawbacks.[57] They may be symptoms of a systemic bias, a rigged process (where an agenda is not published in advance or changed when it becomes clear who is present to consent), fear of speaking one's mind, a lack of creativity (to suggest alternatives) or even a lack of courage (to go further along the same road to a more extreme solution that would not achieve unanimous consent).

Unanimity is achieved when the full group apparently consents to a decision. It has disadvantages insofar as further disagreement, improvements or better ideas then remain hidden, but effectively ends the debate moving it to an implementation phase. Some consider all unanimity a form of groupthink, and some experts propose "coding systems ... for detecting the illusion of unanimity symptom".[58] In Consensus is not Unanimity, long-time progressive change activist Randy Schutt writes:

Many people think of consensus as simply an extended voting method in which everyone must cast their votes the same way. Since unanimity of this kind rarely occurs in groups with more than one member, groups that try to use this kind of process usually end up being either extremely frustrated or coercive. Decisions are never made (leading to the demise of the group), they are made covertly, or some group or individual dominates the rest. Sometimes a majority dominates, sometimes a minority, sometimes an individual who employs "the Block." But no matter how it is done, this coercive process is not consensus.[55]

Confusion between unanimity and consensus, in other words, usually causes consensus decision-making to fail, and the group then either reverts to majority or supermajority rule or disbands.

Most robust models of consensus exclude uniformly unanimous decisions and require at least documentation of minority concerns. Some state clearly that unanimity is not consensus but rather evidence of intimidation, lack of imagination, lack of courage, failure to include all voices, or deliberate exclusion of the contrary views.

Criticism of majority voting processes

[edit]Some proponents of consensus decision-making view procedures that use majority rule as undesirable for several reasons. Majority voting is regarded as competitive, rather than cooperative, framing decision-making in a win/lose dichotomy that ignores the possibility of compromise or other mutually beneficial solutions.[59] Carlos Santiago Nino, on the other hand, has argued that majority rule leads to better deliberation practice than the alternatives, because it requires each member of the group to make arguments that appeal to at least half the participants.[60]

Some advocates of consensus would assert that a majority decision reduces the commitment of each individual decision-maker to the decision. Members of a minority position may feel less commitment to a majority decision, and even majority voters who may have taken their positions along party or bloc lines may have a sense of reduced responsibility for the ultimate decision. The result of this reduced commitment, according to many consensus proponents, is potentially less willingness to defend or act upon the decision.

Majority voting cannot measure consensus. Indeed,—so many 'for' and so many 'against'—it measures the very opposite, the degree of dissent. The Modified Borda Count has been put forward as a voting method which better approximates consensus.[61][31][30]

Additional critical perspectives

[edit]Some formal models based on graph theory attempt to explore the implications of suppressed dissent and subsequent sabotage of the group as it takes action.[62]

High-stakes decision-making, such as judicial decisions of appeals courts, always require some such explicit documentation. Consent however is still observed that defies factional explanations. Nearly 40% of the decisions of the United States Supreme Court, for example, are unanimous, though often for widely varying reasons. "Consensus in Supreme Court voting, particularly the extreme consensus of unanimity, has often puzzled Court observers who adhere to ideological accounts of judicial decision making."[63] Historical evidence is mixed on whether particular Justices' views were suppressed in favour of public unity.[64]

Heitzig and Simmons (2012) suggest using random selection as a fall-back method to strategically incentivize consensus over blocking.[50] However, this makes it very difficult to tell the difference between those who support the decision and those who merely tactically tolerate it for the incentive. Once they receive that incentive, they may undermine or refuse to implement the agreement in various and non-obvious ways. In general voting systems avoid allowing offering incentives (or "bribes") to change a heartfelt vote.

In the Abilene paradox, a group can unanimously agree on a course of action that no individual member of the group desires because no one individual is willing to go against the perceived will of the decision-making body.[65]

Since consensus decision-making focuses on discussion and seeks the input of all participants, it can be a time-consuming process. This is a potential liability in situations where decisions must be made speedily, or where it is not possible to canvass opinions of all delegates in a reasonable time. Additionally, the time commitment required to engage in the consensus decision-making process can sometimes act as a barrier to participation for individuals unable or unwilling to make the commitment.[66] However, once a decision has been reached it can be acted on more quickly than a decision handed down. American businessmen complained that in negotiations with a Japanese company, they had to discuss the idea with everyone even the janitor, yet once a decision was made the Americans found the Japanese were able to act much quicker because everyone was on board, while the Americans had to struggle with internal opposition.[67]

Similar practices

[edit]Outside of Western culture, multiple other cultures have used consensus decision-making. One early example is the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy Grand Council, which used a 75% supermajority to finalize its decisions,[68] potentially as early as 1142.[69] In the Xulu and Xhosa (South African) process of indaba, community leaders gather to listen to the public and negotiate figurative thresholds towards an acceptable compromise. The technique was also used during the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[70][71] In Aceh and Nias cultures (Indonesian), family and regional disputes, from playground fights to estate inheritance, are handled through a musyawarah consensus-building process in which parties mediate to find peace and avoid future hostility and revenge. The resulting agreements are expected to be followed, and range from advice and warnings to compensation and exile.[72][73]

The origins of formal consensus-making can be traced significantly further back, to the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, who adopted the technique as early as the 17th century.[74] Anabaptists, including some Mennonites, have a history of using consensus decision-making[75] and some believe Anabaptists practiced consensus as early as the Martyrs' Synod of 1527.[74] Some Christians trace consensus decision-making back to the Bible. The Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia references, in particular, Acts 15[76] as an example of consensus in the New Testament. The lack of legitimate consensus process in the unanimous conviction of Jesus by corrupt priests[77] in an illegally held Sanhedrin court (which had rules preventing unanimous conviction in a hurried process) strongly influenced the views of pacifist Protestants, including the Anabaptists (Mennonites/Amish), Quakers and Shakers. In particular it influenced their distrust of expert-led courtrooms and to "be clear about process" and convene in a way that assures that "everyone must be heard".[78]

The Modified Borda Count voting method has been advocated as more 'consensual' than majority voting, by, among others, by Ramón Llull in 1199, by Nicholas Cusanus in 1435, by Jean-Charles de Borda in 1784, by Hother Hage in 1860, by Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) in 1884, and by Peter Emerson in 1986.

Japanese business

[edit]Japanese companies normally use consensus decision-making, meaning that unanimous support on the board of directors is sought for any decision.[79] A ringi-sho is a circulation document used to obtain agreement. It must first be signed by the lowest level manager, and then upwards, and may need to be revised and the process started over.[80]

IETF rough consensus model

[edit]In the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), decisions are assumed to be taken by rough consensus.[81] The IETF has studiously refrained from defining a mechanical method for verifying such consensus, apparently in the belief that any such codification leads to attempts to "game the system." Instead, a working group (WG) chair or BoF chair is supposed to articulate the "sense of the group."

One tradition in support of rough consensus is the tradition of humming rather than (countable) hand-raising; this allows a group to quickly discern the prevalence of dissent, without making it easy to slip into majority rule.[82]

Much of the business of the IETF is carried out on mailing lists, where all parties can speak their views at all times.

Social constructivism model

[edit]In 2001, Robert Rocco Cottone published a consensus-based model of professional decision-making for counselors and psychologists.[83] Based on social constructivist philosophy, the model operates as a consensus-building model, as the clinician addresses ethical conflicts through a process of negotiating to consensus. Conflicts are resolved by consensually agreed on arbitrators who are selected early in the negotiation process.

US Bureau of Land Management collaborative stakeholder engagement

[edit]The United States Bureau of Land Management's policy is to seek to use collaborative stakeholder engagement as standard operating practice for natural resources projects, plans, and decision-making except under unusual conditions such as when constrained by law, regulation, or other mandates or when conventional processes are important for establishing new, or reaffirming existing, precedent.[84]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

[edit]The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of 1569–1795 used consensus decision-making in the form of liberum veto ('free veto') in its Sejms (legislative assemblies). A type of unanimous consent, the liberum veto originally allowed any member of a Sejm to veto an individual law by shouting Sisto activitatem! (Latin: "I stop the activity!") or Nie pozwalam! (Polish: "I do not allow!").[85] Over time it developed into a much more extreme form, where any Sejm member could unilaterally and immediately force the end of the current session and nullify any previously passed legislation from that session.[86] Due to excessive use and sabotage from neighboring powers bribing Sejm members, legislating became very difficult and weakened the Commonwealth. Soon after the Commonwealth banned liberum veto as part of its Constitution of 3 May 1791, it dissolved under pressure from neighboring powers.[87]

Sociocracy

[edit]Sociocracy has many of the same aims as consensus and is in applied in a similar range of situations.[88] It is slightly different in that broad support for a proposal is defined as the lack of disagreement (sometimes called 'reasoned objection') rather than affirmative agreement.[89] To reflect this difference from the common understanding of the word consensus, in Sociocracy the process is called gaining 'consent' (not consensus).[90]

See also

[edit]- Consensus based assessment

- Consensus democracy

- Consensus government

- Consensus reality

- Consensus theory of truth

- Contrarian

- Copenhagen Consensus

- Deliberation

- Dialogue mapping

- Ethics of Dissensus

- Jirga

- Libertarian socialism

- Nonviolence

- Polder model

- Quaker decision-making

- Scientific consensus

- Seattle process

- Silent majority

- Social representations

- Sociocracy

- Systemic Consensus

Notes

[edit]- ^ McGann, Anthony J.; Latner, Michael (2013). "The Calculus of Consensus Democracy". Comparative Political Studies. 46 (7): 823–850. doi:10.1177/0010414012463883.

- ^ "consensus". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary, "Consensus", accessed 6 March 2021.

- ^ The Random House Dictionary of the English Language (unabridged)], New York, 1967, p. 312

- ^ Leach, Darcy K. (1 February 2016). "When Freedom Is Not an Endless Meeting: A New Look at Efficiency in Consensus-Based Decision Making". The Sociological Quarterly. 57 (1): 36–70. doi:10.1111/tsq.12137. ISSN 0038-0253. S2CID 147292061.

The popularity of consensus decision making has waxed and waned with the impulse toward participatory democracy and has become more mainstream over time. The last major wave in the United States began in the 1960s, gained momentum in the 1970s ... and peaked in the early 1980s, in the direct action wings of the women's, peace, and antinuclear movements

- ^ a b "Anarchism and the Movement for a New Society: Direct Action and Prefigurative Community in the 1970s and 80s By Andrew Cornell | The Institute for Anarchist Studies". 1 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

Though rarely remembered by name today, many of the new ways of doing radical politics that the Movement for a New Society (MNS) promoted have become central to contemporary anti-authoritarian social movements. MNS popularized consensus decision-making, introduced the spokescouncil method of organization to activists in the United States, and was a leading advocate of a variety of practices—communal living, unlearning oppressive behavior, creating co-operatively owned businesses—that are now often subsumed under the rubric of "prefigurative politics." ... From the outset, MNS members relied on a consensus decision-making process, and rejected domineering forms of leadership prevalent in 1960s radical groups.

- ^ Graeber, David (2010). "The rebirth of anarchism in North America, 1957-2007". Historia Actual Online (21): 123–131. doi:10.36132/hao.v0i21.419. ISSN 1696-2060. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

The main inspiration for anti-nuclear activists—at least the main organizational inspiration—came from a group called the Movement for a New Society (MNS), based in Philadelphia.

- ^ "Anarchism and the Movement for a New Society: Direct Action and Prefigurative Community in the 1970s and 80s By Andrew Cornell | The Institute for Anarchist Studies". 1 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

MNS trainers traveled throughout New England in early 1977, facilitating workshops on non-violent direct action with members and supporters of the Clamshell Alliance, the largest anti-nuclear organization on the East Coast, which was coordinating the action.

- ^ "Anti-Nuclear Protests by Sanderson Beck". san.beck.org. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

The Movement for a New Society (MNS) from Philadelphia had influenced the Clamshell, and David Hartsough, who had also worked for civil rights in the South, brought their nonviolence tactics, affinity group structure, and consensus processes to California

- ^ Resource manual for a living revolution. Virginia Coover. [Philadelphia]: New Society Press. 1977. ISBN 0-686-28494-1. OCLC 3662455.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Blunden, Andy (2016). The origins of collective decision making. Leiden. ISBN 978-90-04-31963-9. OCLC 946968538.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ King, Mary. "Mary E. King » The short and the long of creating democracy". Retrieved 21 May 2022.

In SNCC, we tried to make all decisions by consensus—something in the news earlier this autumn with the Occupy Wall Street movement. The achievement of consensus, however, is far from simple. In SNCC it meant discussing a matter and reformulating it until no objections remained. Everyone and anyone present could speak. Participants included those of us on staff (a SNCC field secretary was paid $10 weekly, $9.64 after tax deductions), but, as time went on, an increasing number of local people would participate as well—individuals whom we were encouraging and coaching for future leadership. Our meetings were protracted and never efficient. Making a major decision might take three days and two nights. This sometimes meant that the decision was in effect made by those who remained and were still awake!

- ^ "Anarchism and the Movement for a New Society: Direct Action and Prefigurative Community in the 1970s and 80s By Andrew Cornell | The Institute for Anarchist Studies". 1 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

Yet, in the later 1960s, both the Black Freedom movement and the student movement, smarting from repression on the one hand, and elated by radical victories at home and abroad on the other, moved away from this emergent, anarchistic, political space distinguished from both liberalism and Marxism. Many civil rights organizers took up nationalist politics in hierarchical organizations, while some of the most committed members of SDS returned to variants of Marxist-Leninism and democratic socialism.

- ^ Swerdlow, Amy (1982). "Ladies' Day at the Capitol: Women Strike for Peace versus HUAC". Feminist Studies. 8 (3): 493–520. doi:10.2307/3177709. hdl:2027/spo.0499697.0008.303. JSTOR 3177709.

Eleanor Garst, one of the Washington founders, explained the attractions of the un-organizational format: "... Any woman who has an idea can propose it through an informal memo system; if enough women think it's good, it's done. Those who don't like a particular action don't have to drop out of the movement; they just sit out that action and wait for one they like."

- ^ "Food Not Bombs". foodnotbombs.net. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

Food Not Bombs started after the May 24, 1980 protest to stop the Seabrook Nuclear power station north of Boston in New Hampshire in the United States.

- ^ Blunden, Andy (2016). The origins of collective decision making. Leiden. ISBN 978-90-04-31963-9. OCLC 946968538.

My next encounter with Consensus was in 2000 at the protest at the World Economic Forum held on 11–13 September that year, known as S11 and modelled on the events the previous year in Seattle. It was the anarchists who had taken the initiative to organise this event and mass meetings were being held to plan the protest for many months leading up to the day. The anarchists were by far the majority in these planning meetings and decided on the agenda and norms for these at their own meeting held elsewhere beforehand, so a fully developed form of Consensus predominated at all the planning meetings.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Hartnett, Tim (26 April 2011). Consensus-Oriented Decision-Making: The CODM Model for Facilitating Groups to Widespread Agreement. New Society Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86571-689-6.

- ^ Rob Sandelin. "Consensus Basics, Ingredients of successful consensus process". Northwest Intentional Communities Association guide to consensus. Northwest Intentional Communities Association. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "Articles on Meeting Facilitation, Consensus, Santa Cruz California". Groupfacilitation.net. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Bressen, Tree (2006). "16. Consensus Decision Making" (PDF). Change Handbook. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2014.

- ^ Kaner, Sam (26 April 2007). Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making. John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 9780787982669.

- ^ Weale, Albert (1999). "Unanimity, Consensus and Majority Rule". Democracy. pp. 124–147. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-27291-4_7. ISBN 978-0-333-56755-5.

- ^ Christian, Diana Leafe (2003). Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities. New Society Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86571-471-7.

- ^ a b "The Consensus Decision Process in Cohousing". Canadian Cohousing Network. Archived from the original on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Richard Bruneau (2003). "If Agreement Cannot Be Reached". Participatory Decision-Making in a Cross-Cultural Context. Canada World Youth. p. 37. Archived from the original (DOC) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Consensus Development Project (1998). "FRONTIER: A New Definition". Frontier Education Center. Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Rachel Williams; Andrew McLeod (2008). "Consensus Decision-Making" (PDF). Cooperative Starter Series. Northwest Cooperative Development Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Dorcas; Ellyntari (2004). "Amazing Graces' Guide to Consensus Process". Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Jeppesen, Sandra; Adamiak, Joanna (2017). "Street Theory: Grassroots Activist Interventions in Regimes of Knowledge". In Haworth, Robert H.; Elmore, John M. (eds.). Out of the Ruins: The Emergence of Radical Informal Learning Spaces. PM Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-62963-319-0.

- ^ a b Emerson, Peter J. (2007). Designing an all-inclusive democracy : consensual voting procedures for use in parliaments, councils and committees. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783540331643. OCLC 184986280.

- ^ a b "What is a modified Borda count?". The de Borda Institute. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "The Basics of Consensus Decision Making". Consensus Decision Making. ConsensusDecisionMaking.org. 17 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ What is Consensus?. The Common Place. 2005. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "The Process". Consensus Decision Making. Seeds for Change. 1 December 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b "A Comparison of Quaker-based Consensus and Robert's Rules of Order". Quaker Foundations of Leadership, 1999. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ Berry, Fran; Snyder, Monteze (1998). "Notes prepared for Round table: Teaching Consensus-building in the Classroom". Quaker Foundations of Leadership, 1999. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ Woodrow, Peter (1999). "BUILDING CONSENSUS AMONG MULTIPLE PARTIES: The Experience of the Grand Canyon Visibility Transport Commission". Program in Quaker Foundations of Leadership. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Our Distinctive Approach". Quaker Foundations of Leadership, 1999. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Public Policy Consensus & Mediation: State of Maine Best Practices - What is a Consensus Process?". Maine.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008.

- ^ a b C.T. Lawrence Butler; Amy Rothstein. "On Conflict and Consensus". Food Not Bombs Publishing. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b Sheila Kerrigan (2004). "How To Use a Consensus Process To Make Decisions". Community Arts Network. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Waller, Lori. "Meeting Facilitation". The Otesha Project. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Berit Lakey (1975). "Meeting Facilitation – The No-Magic Method". Network Service Collaboration. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Haverkamp, Jan (1999). "Non-verbal communication - a solution for complex group settings". Zhaba Facilitators Collective. Archived from the original on 23 February 2005.

- ^ "A Handbook for Direct Democracy and the Consensus Decision Process" (PDF). Zhaba Facilitators Collective. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ "Hand Signals" (PDF). Seeds for Change. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ "Guide for Facilitators: Fist-to-Five Consensus-Building". Freechild.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ The Salt Lake Tribune. "Utah Local News - Salt Lake City News, Sports, Archive - The Salt Lake Tribune".

- ^ Saint, Steven; Lawson, James R. (1994). Rules for Reaching Consensus: A Modern Approach to Decision Making. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-893-84256-7.

- ^ a b Heitzig, Jobst; Simmons, Forest W. (2012). "Some chance for consensus: Voting methods for which consensus is an equilibrium" (PDF). Social Choice and Welfare. 38: 43–57. doi:10.1007/s00355-010-0517-y. S2CID 6560809.

- ^ The Common Wheel Collective (2002). "Introduction to Consensus". The Collective Book on Collective Process. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Alan McCluskey (1999). "Consensus building and verbal desperados". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Welch Cline, Rebecca J (1990). "Detecting groupthink: Methods for observing the illusion of unanimity". Communication Quarterly. 38 (2): 112–126. doi:10.1080/01463379009369748.

- ^ Reagle, Joseph M. Jr. (30 September 2010). "The challenges of consensus". Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia. MIT Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-262-01447-2. Available for free download in multiple formats at: Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia at the Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Schutt, Randy (13 June 2016). "Consensus Is Not Unanimity: Making Decisions Cooperatively". www.vernalproject.org. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Starhawk. "Consensus Decision Making Articles for learning how to use consensus process - Adapted from Randy Schutt". Consensus Decision-Making. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Schermers, Henry G.; Blokker, Niels M. (2011). International Institutional Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 547. ISBN 978-9004187986. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Cline, Rebecca J. Welch (2009). "Detecting groupthink: Methods for observing the illusion of unanimity". Communication Quarterly. 38 (2): 112–126. doi:10.1080/01463379009369748.

- ^ Friedrich Degenhardt (2006). "Consensus: a colourful farewell to majority rule". World Council of Churches. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ McGann, Anthony (2006). The Logic of Democracy: Reconciling Equality, Deliberation, and Minority Protection. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.189565. ISBN 978-0-472-09949-8.

- ^ Rhizome (2 June 2011). "Near-consensus alternatives: Crowd Wise". Welcome to the archived Rhizome website for useful resources. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Inohara, Takehiro (2010). "Consensus building and the Graph Model for Conflict Resolution". 2010 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. pp. 2841–2846. doi:10.1109/ICSMC.2010.5641917. ISBN 978-1-4244-6586-6. S2CID 36860543.

- ^ Epstein, Lee; Segal, Jeffrey A.; Spaeth, Harold J. (2001). "The Norm of Consensus on the U.S. Supreme Court". American Journal of Political Science. 45 (2): 362–377. doi:10.2307/2669346. JSTOR 2669346.

- ^ Edelman, Paul H.; Klein, David E.; Lindquist, Stefanie A. (2012). "Consensus, Disorder, and Ideology on the Supreme Court". Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 9 (1): 129–148. doi:10.1111/j.1740-1461.2011.01249.x. S2CID 142712249.

- ^ Harvey, Jerry B. (Summer 1974). "The Abilene Paradox and other Meditations on Management". Organizational Dynamics. 3 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(74)90005-9.

- ^ "Consensus Team Decision Making". Strategic Leadership and Decision Making. National Defense University. Archived from the original on 27 April 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Tomalin, Barry; Knicks, Mike (2008). "Consensus or individually driven decision-". The World's Business Cultures and How to Unlock Them. Thorogood Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-85418-369-9.

- ^ M. Paul Keesler (2008). "League of the Iroquois". Mohawk – Discovering the Valley of the Crystals. North Country Press. ISBN 9781595310217. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007.

- ^ Bruce E. Johansen (1995). "Dating the Iroquois Confederacy". Akwesasne Notes. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "Climate talks turn to South African indaba process to unlock deal". Reuters. 10 December 2016.

- ^ Rathi, Akshat (12 December 2015). "This simple negotiation tactic brought 195 countries to consensus".

- ^ Anthony, Mely Caballero (2005). Regional Security in Southeast Asia: Beyond the ASEAN Way. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812302601 – via Google Books.

- ^ Asian Development Bank (2009). Complaint handling in the rehabilitation of Aceh and Nias : experiences of the Asian Development Bank and other organizations (PDF). Metro Manila, Philippines. p. 151. ISBN 978-971-561-847-2. OCLC 891386023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Ethan Mitchell (2006). "Participation in Unanimous Decision-Making: The New England Monthly Meetings of Friends". Philica. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Dueck, Abe J. (1990). "Church Leadership: A Historical Perspective". Direction. 19 (2). Kindred Productions: 18–27. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Ralph A Lebold (1989). "Consensus". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Elaine Pagels (1996). The Origin of Satan: How Christians Demonized Jews, Pagans, and Heretics. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-73118-4. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "AT 11: Conflict and Church Decision Making: Be clear about process and let everyone be heard - The Anabaptist Network". Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Ezra F. (1975). Modern Japanese Organization and Decision-making. University of California Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0520054684.

- ^ "Ringi-Sho". Japanese123.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Bradner, Scott (1998). IETF Working Group Guidelines and Procedures. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC2418. RFC 2418. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Hoffman, P.; Harris, S. (September 2006). The Tao of IETF: A novice's guide to the Internet Engineering Task Force. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC4677. FYI 17. RFC 4677.

- ^ Cottone, R. Rocco (2001). "A Social Constructivism Model of Ethical Decision Making in Counseling". Journal of Counseling & Development. 79 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01941.x. ISSN 1556-6676.

- ^ "Bureau of Land Management National Natural Resources Policy for Collaborative Stakeholder Engagement and Appropriate Dispute Resolution" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2012.

- ^ Juliusz, Bardach; Leśnodorski, Bogusław; Pietrzak, Michał (1987). Historia państwa i prawa polskiego. Warszawa: Państ. Wydaw. Naukowe. pp. 220–221.

- ^ Francis Ludwig Carsten (1975) [1961]. The new Cambridge modern history: The ascendancy of France, 1648–88. CUP Archive. pp. 561–562. ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Ekiert, Grzegorz (1998). Lipset, Seymour Martin (ed.). "Veto, Liberum". The Encyclopedia of Democracy. 4: 1341.

- ^ Buck, John., Villines, Sharon. We the People: Consenting to a Deeper Democracy. United States Sociocracy. Info Press, 2017.

- ^ Rau, Ted. Sociocracy - a Brief Introduction. N.p.: Sociocracy For All, 2022.

- ^ Rau, Ted J., Koch-Gonzalez, Jerry. Many Voices One Song: Shared Power with Sociocracy. United States Sociocracy For All, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Leach, Darcy K. (February 2016). "When Freedom Is Not an Endless Meeting: A New Look at Efficiency in Consensus-Based Decision Making". The Sociological Quarterly. 57 (1): 36–70. doi:10.1111/tsq.12137. ISSN 0038-0253. S2CID 147292061.