Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electoral system

View on Wikipedia| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

An "electoral system" is the term for the Group decision-making procedure of a group with a common goal, which could be called "Common goal group decision-making procedure". Whereas a common goal is the goal of a group of people, who may or may not be bound together to practice and inform people not of the group of their common goal. For various reasons, it is worth mentioning, that, erroneously, a common goal might be assumed to be the same as a "shared goal". However, a common goal is not a shared goal, since the goal of an individual human is not a portion of a whole, but is completely, separately, and equally respectively part of the resources that one individual has and uses to satisfy it's basic needs. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, nonprofit organizations and informal organisations. These rules govern all aspects of the voting process: when elections occur, who is allowed to vote, who can stand as a candidate, how ballots are marked and cast, how the ballots are counted, how votes translate into the election outcome, limits on campaign spending, and other factors that can affect the result. Political electoral systems are defined by constitutions and electoral laws, are typically conducted by election commissions, and can use multiple types of elections for different offices.

Some electoral systems elect a single winner to a unique position, such as prime minister, president or governor, while others elect multiple winners, such as members of parliament or boards of directors. When electing a legislature, areas may be divided into constituencies with one or more representatives or the electorate may elect representatives as a single unit. Voters may vote directly for an individual candidate or for a list of candidates put forward by a political party or alliance. There are many variations in electoral systems.

The mathematical and normative study of voting rules falls under the branches of economics called social choice and mechanism design, but the question has also engendered substantial contributions from political scientists, analytic philosophers, computer scientists, and mathematicians. The field has produced several major results, including Arrow's impossibility theorem (showing that ranked voting cannot eliminate the spoiler effect) and Gibbard's theorem (showing it is impossible to design a straightforward voting system, i.e. one where it is always obvious to a strategic voter which ballot they should cast).

Types

[edit]The most common categorizations of electoral systems are: single-winner vs. multi-winner systems and proportional representation vs. winner-take-all systems vs. mixed systems.

Single-winner and winner-take-all systems

[edit]In all cases, where only a single winner is to be elected, the electoral system is winner-take-all. The same can be said for elections where only one person is elected per district. Since district elections are winner-take-all, the electoral system as a whole produces dis-proportional results. Some systems where multiple winners are elected at once (in the same district), such a plurality block voting are also winner-take-all.

In party block voting, voters can only vote for the list of candidates of a single party, with the party receiving the most votes winning all seats, even if that party receives only a minority of votes. This is also described as winner-take-all. This is used in five countries as part of mixed systems.[1]

Plurality voting - first past the post and block voting

[edit]

Plurality voting is a system in which the candidate(s) with the largest number of votes wins, with no requirement to get a majority of votes. In cases where there is a single position to be filled, it is known as first-past-the-post. This is the second-most-common electoral system for national legislatures (after proportional representation). Altogether at least 58 countries use FPTP and single-member districts to elect all or some of the members of a national-level legislative chamber,[1] the vast majority of which are current or former British colonies or U.S. territories. It is also the second-most-common system used for presidential elections, being used in 19 countries. The two-round system is the most common system used to elect a president.[1]

In cases where there are multiple positions to be filled, most commonly in cases of multi-member constituencies, there are several types of plurality electoral systems. Under block voting (also known as multiple non-transferable vote or plurality-at-large), voters have as many votes as there are seats and can vote for any candidate, regardless of party, but give only one vote to each preferred candidate. The most-popular candidates are declared elected, whether they have a majority of votes or not and whether or not that result is proportional to the way votes were cast. Eight countries use this system.[1]

Cumulative voting allows a voter to cast more than one vote for the same candidate, in multi-member districts. Its effect may be proportional to the same degree that single non-transferable voting or limited voting is, thus it is often called semi-proportional.

Approval voting is a choose-all-you-like voting system that aims to increase the number of candidates that win with majority support.[2] Voters are free to pick as many candidates as they like and each choice has equal weight, independent of the number of candidates a voter supports. The candidate with the most votes wins.[3]

Runoff systems

[edit]

A runoff system is one in which a candidates receives a majority of votes to be elected, either in a runoff election or final round of vote counting. This is sometimes referred to as a way to ensure that a winner must have a majority of votes, although usually only a plurality is required in the last round (when three or more candidates move on to the runoff election), and sometimes even in the first round winners can avoid a second round without achieving a majority. In social choice theory, runoff systems are not called majority voting, as this term refers to Condorcet-methods.

There are two main groups of runoff systems, those in one group use a single round of voting achieved by voters casting ranked votes and then using vote transfers if necessary to establish a majority, and those in the other group use two or more rounds of voting, to narrow the field of candidates and to determine a winner who has a majority of the votes. Both are primarily used for single-member constituencies or election of a single position such as mayor.

If a candidate receives a majority of the vote in the first round, then the system is simple first past the post voting. But if no one has a majority of votes in first round, the systems respond in different ways.

Under instant-runoff voting (IRV), when no one wins a majority in first round, runoff is achieved through vote transfers made possible by voters having ranked candidates in order of preference, with lower preferences used as back-up preferences. This system is used for parliamentary elections in Australia and Papua New Guinea. If no candidate receives a majority of the vote in the first round, the votes of the least-popular candidate are transferred as per marked second preferences and added to the totals of surviving candidates. This is repeated until a candidate achieves a majority. The count ends any time one candidate has a majority of votes but it may continue until only two candidates remain, at which point one or other of the candidates will take a majority of votes still in play.

A different form of single-winner preferential voting is the contingent vote where voters do not rank all candidates, but rank just two or three. If no candidate has a majority in the first round, all candidates except the top two are excluded. If the voter gave first preference to one of the excluded candidates, the vote is transferred to the next usable back-up preferences if possible, or otherwise put in the exhausted pile. The resulting vote totals are used to determine the winner by majority. This system is used in Sri Lankan presidential elections, with voters allowed to give three preferences.[4]

The other main form of runoff system is the two-round system, which is the most common system used for presidential elections around the world, being used in 88 countries. It is also used, in conjunction with single-member districts, in 20 countries for electing members of the legislature.[1] If no candidate achieves a majority of votes in the first round of voting, a second round is held to determine the winner. In most cases the second round is limited to the top two candidates from the first round, although in some elections more than two candidates may choose to contest the second round; in these cases the second-round winner is not required to have a majority of votes, but may be elected by having a plurality of votes.

Some countries use a modified form of the two-round system, so going to a second round happens less often. In Ecuador a candidate in the presidential election is declared the winner if they receive more than 50 percent of the vote or 40% of the vote and are 10% ahead of their nearest rival,[5] In Argentina, where the system is known as ballotage, election is achieved by those with majority or if they have 45% and a 10% lead.

In some cases, where a certain level of support is required, a runoff may be held using a different system. In U.S. presidential elections, when no candidate wins a majority of the United States Electoral College (using seat count, not votes cast, as is used in the majoritarian systems described above), a contingent election is held by the House of Representatives, not the voters themselves. The House contingency election sees three candidates go on to the last round and the Representatives of each state vote as a single unit, not as individuals, with the state's votes going to the plurality winner of the State members' votes.

An exhaustive ballot sees multiple rounds of voting (where no one has majority in first round). The number of rounds is not limited to two rounds, but sees the last-placed candidate eliminated in each round of voting, repeated until one candidate has majority of votes. Due to the potentially large number of rounds, this system is not used in any major popular elections, but is used to elect the Speakers of parliament in several countries and members of the Swiss Federal Council.

In some systems, such as election of the speaker of the United States House of Representatives, there may be multiple rounds held without any candidates being eliminated (unless by a candidate's own resignation) until a candidate achieves a majority.

Positional systems

[edit]Positional systems like the Borda Count are ranked voting systems that assign a certain number of points to each candidate, weighted by position. The most popular such system is first-preference plurality. Another well-known variant, the Borda count, each candidate is given a number of points equal to their rank, and the candidate with the least points wins. This system is intended to elect broadly acceptable options or candidates, rather than those preferred by a majority.[6] This system is used to elect the ethnic minority representatives seats in the Slovenian parliament.[7][8]

The Dowdall system is used in Nauru for parliamentary elections and sees voters rank the candidates. First preference votes are counted as whole numbers, the second preferences by two, third preferences by three, and so on; this continues to the lowest possible ranking.[9] The totals for each candidate determine the winners.[10]

Multi-winner systems

[edit]Multi-winner systems include both proportional systems and non-proportional multi-winner systems, such as party block voting and plurality block voting. A voter can cast one vote, as many votes as the number of seats to fill, or something in between (limited voting).

Proportional systems

[edit]

Proportional representation is the most widely used type of electoral system to elect national legislatures. All or some members of the parliaments of over a hundred countries are elected by a form of PR.[11] These systems elect multiple members in one contest, whether that is at-large, as in a city-wide election at the city level or state-wide or nation-wide at those levels, or in multi-member districts at any level.

Party-list proportional representation is the single most common electoral system and is used by 80 countries, and involves seats being allocated to parties based on party vote share.

In closed list systems voters do not have any influence over which candidates are elected to fill the party seats, but in open list systems voters are able to both vote for the party list and for candidates (or only for candidates). Voters thus have means to sometimes influence the order in which party candidates will be assigned seats. In some countries, notably Israel and the Netherlands, elections are carried out using 'pure' proportional representation, with the votes tallied on a national level before assigning seats to parties. (There are no district seats, only at-large.) However, in most cases several multi-member constituencies are used rather than a single nationwide constituency, giving an element of geographical or local representation. Such may result in the distribution of seats not reflecting the national vote totals of parties. As a result, some countries that use districts have leveling seats that are awarded to some of the parties whose seat proportion is lower than their proportion of the vote. Levelling seats are either used at the regional level or at the national level. Such mixed member proportional systems are used in New Zealand and in Scotland. (They are discussed below.)

List PR systems usually set an electoral threshold, the minimum percentage of the vote that a party must obtain to win levelling seats or to win seats at all. Some systems allow a go around of this rule. For instance, if a party takes a district seat, the party may be eligible for top-up seats even if its percentage of the votes is below the threshold.

Different methods are used to allocate seats in proportional representation systems. Party-list systems use two main methods: highest average and largest remainder. Highest average systems involve dividing the votes received by each party by a divisor or vote average that represents an idealized seats-to-votes ratio, then rounding normally. In the largest remainder system, parties' vote shares are divided by an electoral quota. This usually leaves some seats unallocated, which are awarded to parties based on which parties have the largest number of "leftover" votes.

Single transferable vote (STV) elects multiple winners in a single contest using multi-member districts. Each voter casts a ballot with first preference and optionally ranking other candidates, rather than voting for a party list or marking just one X vote, as in first past the post. In STV, the secondary marked preferences are used as contingency votes, used only if needed. STV is used in Malta, the Republic of Ireland and Australia (partially). To be certain of being elected, a candidate must achieve a quota (the Droop quota being the most common). Candidates that achieve the quota are elected. If necessary to fill seats, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the votes cast for them are redistributed to the second preferences on the ballots in question. Surplus votes held by elected candidates may also be transferred. Eventually all seats are filled by candidates who have passed the quota or by those still in the running when there are only as many remaining candidates as the number of remaining open seats.[10]

Under single non-transferable vote (SNTV), multi-member districts are used. Each voter can vote for only one candidate, with the candidates receiving the most votes declared the winners, whether any of them have a majority of votes or not. This system, often described as semi-proportional, is used in Kuwait, the Pitcairn Islands and Vanuatu and formerly in Japan.[1]

Mixed systems

[edit]

Compensatory

In several countries, mixed systems are used to elect the legislature. These include parallel voting, mixed-member majoritarian, and mixed-member proportional representation.

In non-compensatory, parallel voting systems, which are used in 20 countries,[1] members of a legislature are elected by two different methods; part of the membership is elected by a plurality or majoritarian election system in single-member constituencies and the other part by proportional representation. The results of the constituency contests have no effect on the outcome of the proportional vote.[10]

In compensatory mixed-member systems levelling seats are allocated to balance nation-wide or regional disproportionality produced by the way seats are won in constituency contests. The mixed-member proportional systems, in use in eight countries, provide enough compensatory seats to ensure that many parties have a share of seats approximately proportional to their vote share.[1] Most of the MMP countries use a PR system at the district level, thus lowering the number of levelling seats that are needed to produce proportional results. Of the MMP countries, only New Zealand and Lesotho use single-winner first-past-the-post voting in their districts. Scotland uses a regionalized MMP system where levelling seats are allocated in each region to balance the disproportionality produced in single-winner districts within the region. Variations of this include the Additional Member System, and Alternative Vote Plus, in which voters cast votes for both single-member constituencies and multi-member constituencies; the allocation of seats in the multi-member constituencies is adjusted to achieve an overall seat allocation proportional to parties' vote share by taking into account the number of seats won by parties in the single-member constituencies.

Some MMP systems are insufficiently compensatory, and this may result in overhang seats, where parties win more seats in the constituency system than they would be entitled to based on their vote share. Some MMP systems have mechanism (another form of top-up) where additional seats are awarded to the other parties to balance out the effect of the overhang. Germany in 2024 passed a new election law where district overhang seats may be denied, over-riding the district result in the pursuit of overall proportionality.[12]

Vote linkage mixed systems are also compensatory, however they usually use different mechanism than seat linkage (top-up) method of MMP and usually aren't able to achieve proportional representation.

Some electoral systems feature a majority bonus system to either ensure one party or coalition gains a majority in the legislature, or to give the party receiving the most votes a clear advantage in terms of the number of seats. San Marino has a modified two-round system, which sees a second round of voting featuring the top two parties or coalitions if no party takes a majority of votes in the first round. The winner of the second round is guaranteed 35 seats in the 60-seat Grand and General Council.[13] In Greece the party receiving the most votes was given an additional 50 seats,[14] a system which was abolished following the 2019 elections.

Primary elections

[edit]Primary elections are a feature of some electoral systems, either as a formal part of the electoral system or informally by choice of individual political parties as a method of selecting candidates, as is the case in Italy. Primary elections limit the possible adverse effect of vote splitting by ensuring that a party puts forward only one party candidate. In Argentina they are a formal part of the electoral system and take place two months before the main elections; any party receiving less than 1.5% of the vote is not permitted to contest the main elections.

In the United States, there are both partisan and non-partisan primary elections. In non-partisan primaries, the most-popular nominees, even if only one party, are put forward to the election.

Indirect elections

[edit]Some elections feature an indirect electoral system, whereby there is either no popular vote, or the popular vote is only one stage of the election; in these systems the final vote is usually taken by an electoral college. In several countries, such as Mauritius or Trinidad and Tobago, the post of President is elected by the legislature. In others like India, the vote is taken by an electoral college consisting of the national legislature and state legislatures. In the United States, the president is indirectly elected using a two-stage process; a popular vote in each state elects members to the electoral college that in turn elects the President. This can result in a situation where a candidate who receives the most votes nationwide does not win the electoral college vote, as most recently happened in 2000 and 2016.

Proposed and lesser-used systems

[edit]In addition to the current electoral systems used for political elections, there are numerous other systems that have been used in the past, are currently used only in private organizations (such as electing board members of corporations or student organizations), or have never been fully implemented.

Winner-take-all systems

[edit]Among the Ranked systems these include Bucklin voting, the various Condorcet methods (Copeland's, Dodgson's, Kemeny-Young, Maximal lotteries, Minimax, Nanson's, Ranked pairs, Schulze), the Coombs' method and positional voting.

Among the Cardinal electoral systems, the most well known of these is range voting, where any number of candidates are scored from a set range of numbers. A very common example of range voting are the 5-star ratings used for many customer satisfaction surveys and reviews. Other cardinal systems include satisfaction approval voting, highest median rules (including the majority judgment), and the D21 – Janeček method where voters can cast positive and negative votes.

Historically, weighted voting systems were used in some countries. These allocated a greater weight to the votes of some voters than others, either indirectly by allocating more seats to certain groups (such as the Prussian three-class franchise), or by weighting the results of the vote. The latter system was used in colonial Rhodesia for the 1962 and 1965 elections. The elections featured two voter rolls (the 'A' roll being largely European and the 'B' roll largely African); the seats of the House Assembly were divided into 50 constituency seats and 15 district seats. Although all voters could vote for both types of seats, 'A' roll votes were given greater weight for the constituency seats and 'B' roll votes greater weight for the district seats. Weighted systems are still used in corporate elections, with votes weighted to reflect stock ownership.

Proportional systems

[edit]Dual-member proportional representation is a proposed system with two members elected to represent each constituency, one with the most votes cast in the district and one to ensure proportionality of the combined results using votes cast in the district and elsewhere. Biproportional apportionment is a system where the total number of votes is used to calculate the number of seats each party is due, followed by a calculation of the constituencies in which the seats should be awarded in order to achieve the total due to them.

Proportional systems that use ranked choice voting include STV and STV variants, such as CPO-STV, Schulze STV and the Wright system.

Among the proportional voting systems that use rating are Thiele's voting rules and Phragmen's voting rule. A special case of Thiele's voting rules is Proportional Approval Voting. Some proportional systems that may be used with either ranking or rating include the Method of Equal Shares and the Expanding Approvals Rule.

Rules and regulations

[edit]In addition to the specific method of electing candidates, electoral systems are also characterised by their wider rules and regulations, which are usually set out in a country's constitution or electoral law. Participatory rules determine candidate nomination and voter registration, in addition to the location of polling places and the availability of online voting, postal voting, and absentee voting. Other regulations include the selection of voting devices such as paper ballots, machine voting or open ballot systems, and consequently the type of vote counting systems, verification and auditing used.

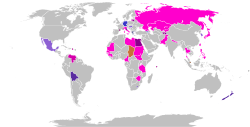

Compulsory voting, not enforced

Compulsory voting, enforced (only men)

Compulsory voting, not enforced (only men)

Historical: the country had compulsory voting in the past.

Electoral rules place limits on suffrage and candidacy. Most countries's electorates are characterised by universal suffrage, but there are differences on the age at which people are allowed to vote, with the youngest being 16 and the oldest 21. People may be disenfranchised for a range of reasons, such as being a serving prisoner, being declared bankrupt, having committed certain crimes or being a serving member of the armed forces. Similar limits are placed on candidacy (also known as passive suffrage), and in many cases the age limit for candidates is higher than the voting age. A total of 21 countries have compulsory voting, although in some there is an upper age limit on enforcement of the law.[15] Many countries also have the none of the above option on their ballot papers.

In systems that use constituencies, apportionment or districting defines the area covered by each constituency. Where constituency boundaries are drawn has a strong influence on the likely outcome of elections in the constituency due to the geographic distribution of voters. Political parties may seek to gain an advantage during redistricting by ensuring their voter base has a majority in as many constituencies as possible, a process known as gerrymandering. Historically rotten and pocket boroughs, constituencies with unusually small populations, were used by wealthy families to gain parliamentary representation.

Some countries have minimum turnout requirements for elections to be valid. In Serbia this rule caused multiple re-runs of presidential elections, with the 1997 election re-run once and the 2002 elections re-run three times due insufficient turnout in the first, second and third attempts to run the election. The turnout requirement was scrapped prior to the fourth vote in 2004.[16] Similar problems in Belarus led to the 1995 parliamentary elections going to a fourth round of voting before enough parliamentarians were elected to make a quorum.[17]

Reserved seats are used in many countries to ensure representation for ethnic minorities, women, young people or the disabled. These seats are separate from general seats, and may be elected separately (such as in Morocco where a separate ballot is used to elect the 60 seats reserved for women and 30 seats reserved for young people in the House of Representatives), or be allocated to parties based on the results of the election; in Jordan the reserved seats for women are given to the female candidates who failed to win constituency seats but with the highest number of votes, whilst in Kenya the Senate seats reserved for women, young people and the disabled are allocated to parties based on how many seats they won in the general vote. Some countries achieve minority representation by other means, including requirements for a certain proportion of candidates to be women, or by exempting minority parties from the electoral threshold, as is done in Poland,[18] Romania and Serbia.[19]

History

[edit]Pre-democratic

[edit]In ancient Greece and Italy, the institution of suffrage already existed in a rudimentary form at the outset of the historical period. In the early monarchies it was customary for the king to invite pronouncements of his people on matters in which it was prudent to secure its assent beforehand. In these assemblies the people recorded their opinion by clamouring (a method which survived in Sparta as late as the 4th century BCE), or by the clashing of spears on shields.[20]

Early democracy

[edit]Voting has been used as a feature of democracy since the 6th century BCE, when democracy was introduced by the Athenian democracy. However, in Athenian democracy, voting was seen as the least democratic among methods used for selecting public officials, and was little used, because elections were believed to inherently favor the wealthy and well-known over average citizens. Viewed as more democratic were assemblies open to all citizens, and selection by lot, as well as rotation of office.

Generally, the taking of votes was effected in the form of a poll. The practice of the Athenians, which is shown by inscriptions to have been widely followed in the other states of Greece, was to hold a show of hands, except on questions affecting the status of individuals: these latter, which included all lawsuits and proposals of ostracism, in which voters chose the citizen they most wanted to exile for ten years, were determined by secret ballot (one of the earliest recorded elections in Athens was a plurality vote that it was undesirable to win, namely an ostracism vote). At Rome the method which prevailed up to the 2nd century BCE was that of division (discessio). But the system became subject to intimidation and corruption. Hence a series of laws enacted between 139 and 107 BCE prescribed the use of the ballot (tabella), a slip of wood coated with wax, for all business done in the assemblies of the people. For the purpose of carrying resolutions a simple majority of votes was deemed sufficient. As a general rule equal value was made to attach to each vote; but in the popular assemblies at Rome a system of voting by groups was in force until the middle of the 3rd century BCE by which the richer classes secured a decisive preponderance.[20]

Most elections in the early history of democracy were held using plurality voting or some variant, but as an exception, the state of Venice in the 13th century adopted approval voting to elect their Great Council.[21]

The Venetians' method for electing the Doge was a particularly convoluted process, consisting of five rounds of drawing lots (sortition) and five rounds of approval voting. By drawing lots, a body of 30 electors was chosen, which was further reduced to nine electors by drawing lots again. An electoral college of nine members elected 40 people by approval voting; those 40 were reduced to form a second electoral college of 12 members by drawing lots again. The second electoral college elected 25 people by approval voting, which were reduced to form a third electoral college of nine members by drawing lots. The third electoral college elected 45 people, which were reduced to form a fourth electoral college of 11 by drawing lots. They in turn elected a final electoral body of 41 members, who ultimately elected the Doge. Despite its complexity, the method had certain desirable properties such as being hard to game and ensuring that the winner reflected the opinions of both majority and minority factions.[22] This process, with slight modifications, was central to the politics of the Republic of Venice throughout its remarkable lifespan of over 500 years, from 1268 to 1797.

Development of new systems

[edit]Jean-Charles de Borda proposed the Borda count in 1770 as a method for electing members to the French Academy of Sciences. His method was opposed by the Marquis de Condorcet, who proposed instead the method of pairwise comparison that he had devised. Implementations of this method are known as Condorcet methods. He also wrote about the Condorcet paradox, which he called the intransitivity of majority preferences. However, recent research has shown that the philosopher Ramon Llull devised both the Borda count and a pairwise method that satisfied the Condorcet criterion in the 13th century. The manuscripts in which he described these methods had been lost to history until they were rediscovered in 2001.[23]

Later in the 18th century, apportionment methods came to prominence due to the United States Constitution, which mandated that seats in the United States House of Representatives had to be allocated among the states proportionally to their population, but did not specify how to do so.[24] A variety of methods were proposed by statesmen such as Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Daniel Webster. Some of the apportionment methods devised in the United States were in a sense rediscovered in Europe in the 19th century, as seat allocation methods for the newly proposed method of party-list proportional representation. The result is that many apportionment methods have two names; Jefferson's method is equivalent to the D'Hondt method, as is Webster's method to the Sainte-Laguë method, while Hamilton's method is identical to the Hare largest remainder method.[24]

The single transferable vote (STV) method was devised by Carl Andræ in Denmark in 1855 and in the United Kingdom by Thomas Hare in 1857. STV elections were first held in Denmark in 1856, and in Tasmania in 1896 after its use was promoted by Andrew Inglis Clark. Over the course of the 20th century, STV was subsequently adopted by Ireland and Malta for their national elections, in Australia for their Senate elections, as well as by many municipal elections around the world.[25]

Party-list proportional representation began to be used to elect European legislatures in the early 20th century, with Belgium the first to implement it for its 1900 general elections. Since then, proportional and semi-proportional methods have come to be used in almost all democratic countries, with most exceptions being former British and French colonies.

Single-winner innovations

[edit]Perhaps influenced by the rapid development of multiple-winner STV, theorists published new findings about single-winner methods in the late 19th century. Around 1870, William Robert Ware proposed applying STV to single-winner elections, yielding instant-runoff voting (IRV). Soon, mathematicians began to revisit Condorcet's ideas and invent new methods for Condorcet completion; Edward J. Nanson combined the newly described instant runoff voting with the Borda count to yield a new Condorcet method called Nanson's method. Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, proposed the straightforward Condorcet method known as Dodgson's method. He also proposed a proportional representation system based on multi-member districts, quotas as minimum requirements to take seats, and votes transferable by candidates through proxy voting.[26]

Ranked voting electoral systems eventually gathered enough support to be adopted for use in government elections. In Australia, IRV was first adopted in 1893 and STV in 1896 (Tasmania). IRV continues to be used along with STV today.

In the United States, during the early 20th-century progressive era some municipalities began to use supplementary voting and Bucklin voting. However, a series of court decisions ruled Bucklin to be unconstitutional, while supplementary voting was soon repealed in every city that had implemented it.[27]

The use of game theory to analyze electoral systems led to discoveries about the effects of certain methods. Earlier developments such as Arrow's impossibility theorem had already shown the issues with ranked voting systems. Research led Steven Brams and Peter Fishburn to formally define and promote the use of approval voting in 1977.[28] Political scientists of the 20th century published many studies on the effects that the electoral systems have on voters' choices and political parties,[29][30][31] and on political stability.[32][33] A few scholars also studied which effects caused a nation to switch to a particular electoral system.[34][35][36][37][38]

Recent reform efforts

[edit]A new push for electoral reform occurred in the 1990s, when proposals were made to replace plurality voting in governmental elections with other methods. New Zealand adopted mixed-member proportional representation for the 1996 general elections, having been approved in a 1993 referendum.[39] After plurality voting was a factor in the contested results of the 2000 presidential elections in the United States, various municipalities in the United States have begun to adopt instant-runoff voting. In 2020 a referendum adopting approval voting in St. Louis passed with 70% support.[40]

In Canada, three separate referendums on the single transferable vote have been held but producing no reform (in 2005, 2009, and 2018). The 2020 Massachusetts Question 2, which attempted to expand instant-runoff voting into Massachusetts, was defeated by a 10-point margin. In the United Kingdom, a 2011 referendum on IRV saw the proposal rejected by a two-to-one margin.

Repeals and backlash

[edit]Some cities that adopted instant-runoff voting subsequently returned to first-past-the-post. Studies have found voter satisfaction with IRV falls dramatically the first time a race produces a result different from first-past-the-post.[41] The United Kingdom used a form of instant-runoff voting for local elections prior to 2022, before returning to first-past-the-post over concerns regarding the system's complexity.[42] Ranked-choice voting has been implemented in two states and banned in 10 others[43] (in addition to other states with constitutional prohibitions on the rule).

In November 2024, voters in the U.S. decided on 10 ballot measures related to electoral systems. Nine of the ballot measures aimed to change existing electoral systems, and voters rejected each proposal. One, in Missouri, which banned ranked-choice voting (RCV), was approved. Voters rejected ballot measures to enact ranked-choice voting and other electoral system changes in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Oregon, as well as in Montana and South Dakota. In Alaska, voters rejected a ballot initiative 50.1% to 49.9% to repeal the state's top-four primaries and ranked-choice voting general elections, a system that was adopted via ballot measure in 2020.[44]

Comparison

[edit]Electoral systems can be compared by different means:

- Define criteria mathematically, such that any electoral system either passes or fails. This gives perfectly objective results, but their practical relevance is still arguable.

- Define ideal criteria and use simulated elections to see how often or how close various methods fail to meet the selected criteria. This gives results which are practically relevant, but the method of generating the sample of simulated elections can still be arguably biased.

- Consider criteria that can be more easily measured using real-world elections, such as the Gallagher index, political fragmentation, voter turnout,[45][46] wasted votes, political apathy, complexity of vote counting, and barriers to entry for new political movements[47] and evaluate each method based on how they perform in real-world elections or evaluate the performance of countries with these electoral systems.

- A 2019 peer-reviewed meta-analysis based on 1,037 regressions in 46 studies finds that countries with majoritary kind of electoral rules would be more "fiscally virtuous" since they would exhibit better fiscal balances in the pre-electoral period, which may be explained by less spending distortion.[48] The meta-analysis also notes that countries with proportional kind of electoral rules would have bigger pre-electoral revenue cuts than other countries.[49]

Gibbard's theorem, built upon the earlier Arrow's theorem and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem, to prove that for any single-winner deterministic voting methods, at least one of the following three properties must hold:

- The process is dictatorial, i.e. there is a single voter whose vote chooses the outcome.

- The process limits the possible outcomes to two options only.

- The process is not straightforward; the optimal ballot for a voter "requires strategic voting", i.e. it depends on their beliefs about other voters' ballots.

According to a 2005 survey of electoral system experts, their preferred electoral systems were in order of preference:[50]

- Mixed member proportional

- Single transferable vote

- Open list proportional

- Alternative vote

- Closed list proportional

- Single member plurality

- Runoffs

- Mixed member majoritarian

- Single non-transferable vote

Systems by elected body

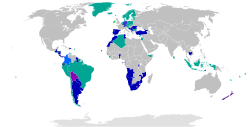

[edit] Head of state |

Lower house or unicameral legislature |

Upper house |

|---|---|---|

First past the post (FPTP)

Two-round system (TRS)

Election by legislature

Election by electoral college

Not elected (mostly monarchies)

In transition

No information

|

Single-member constituencies:

First past the post (FPTP)

Two-round system (TRS)

Instant-runoff voting (IRV)

Multi-member constituencies, majoritarian: Block voting (BV) or mixed FPTP and BV

Party block voting (PBV) or mixed FPTP and PBV

Single non-transferable vote (SNTV) or mixed FPTP and SNTV

Modified Borda count

Multi-member constituencies, proportional: Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, closed list)

Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, open list for some parties)

Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, open list)

Panachage (party-list PR, free list)

Personalised proportional representation (party-list PR and FPTP)

Mixed majoritarian and proportional: Additional member system (party-list PR and FPTP seat linkage mixed system) (less proportional implementation of MMP)

Parallel voting / mixed member majoritarian (party-list PR and FPTP)

Parallel voting (party-list PR and TRS)

Parallel voting (party-list PR and BV or PBV)

Vote linkage mixed system or limited Seat linkage mixed system (party-list PR and FPTP) ((partially compensatory semi-proportional implementation of MMP) (party-list PR and FPTP)

Majority bonus system (non-compensatory)

Majority jackpot system (compensatory)

No relevant electoral system information: No elections

Varies by state

No information |

Single-member constituencies:

First past the post (FPTP)

Two-round system (TRS)

Multi-member constituencies, majoritarian: Block voting (BV) or mixed FPTP and BV

Party block voting (PBV) or mixed FPTP and PBV

Single non-transferable vote (SNTV) or mixed FPTP and SNTV

Mixed BV and SNTV

Multi-member constituencies, proportional: Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, closed list)

Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, open list)

Party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, partially-open list)

Partially party-list proportional representation (party-list PR, closed list)

Mixed majoritarian and proportional: Parallel voting / Mixed-member majoritarian (party-list PR and FPTP)

Parallel voting (party-list PR and BV or PBV)

Parallel voting (party-list PR and SNTV)

Other: Varies by federal states, or constituency

Indirect election: Election by electoral college or local/regional legislatures

Partly elected by electoral college or local/regional legislatures and appointed by head of state

Partly elected by electoral college or local/regional legislatures, partly elected in single-member districts by FPTP, and partly appointed by head of state

No relevant electoral system information: No elections

Appointed by head of state

No information / In transition

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Table of Electoral Systems Worldwide Archived 2017-05-23 at the Wayback Machine IDEA

- ^ Fenster, Mark (1983). "Approval Voting: Do Moderates Gain?". Political Methodology. 9 (4): 355–376. JSTOR 25791202. Retrieved 2024-05-24.

- ^ "What is Approval Voting?". Election Science. The Center for Election Science. Retrieved 2024-05-24.

Voters can vote for as many candidates as they want. The votes are tallied, and the candidate with the most votes wins!

- ^ Sri Lanka: Election for President IFES

- ^ Ecuador: Election for PresidentArchived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine IFES

- ^ Lippman, David. Voting Theory opentextbookstore.com

- ^ Filipovska, Majda (1998), "Republic of Slovenia. The Documentation and Library Department of the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia", Parliamentary Libraries and Research Services in Central and Eastern Europe, De Gruyter Saur, pp. 194–207, doi:10.1515/9783110954098.194, ISBN 978-3-598-21813-2, retrieved 2023-11-13

- ^ "How do elections work in Slovenia?". www.electoral-reform.org.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Nauru Parliament: Electoral system IPU

- ^ a b c Glossary of Terms Archived 2017-06-11 at the Wayback Machine IDEA

- ^ "How many countries around the world use PR?" https://electoral-reform.org.uk/how-many-countries-around-the-world-use-proportional-representation/ accessed 2025-10-17

- ^ "Overhang seats" https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/en/service/glossar/u/ueberhangmandate.html accessed March 19, 2025

- ^ Consiglio grande e generale: Electoral system IPU

- ^ Hellenic Parliament: Electoral system IPU

- ^ Suffrage Archived 2008-01-09 at the Wayback Machine CIA World Factbook

- ^ Pro-Western Candidate Wins Serbian Presidential Poll Deutsche Welle, 28 June 2004

- ^ Elections held in 1995 IPU

- ^ Sejm: Electoral system IPU

- ^ Narodna skupstina: Electoral system IPU

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vote and Voting". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 216.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E. F. (August 2002). "The history of voting". MacTutor History of Mathematics. Archived from the original on Apr 11, 2021.

- ^ Miranda Mowbray and Dieter Gollmann (2007) Electing the Doge of Venice: Analysis of a 13th Century Protocol

- ^ G. Hägele and F. Pukelsheim (2001) "Llull's writings on electoral systems", Studia Lulliana Vol. 3, pp. 3–38

- ^ a b Apportionment: Introduction American Mathematical Society

- ^ Farrell, David M.; McAllister, Ian (2006). The Australian Electoral System. UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868408583. Archived from the original on 6 December 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ Charles Dodgson (1884) Principles of Parliamentary Representation

- ^ Tony Anderson Solgård and Paul Landskroener (2002) "Municipal Voting System Reform: Overcoming the Legal Obstacles", Bench & Bar of Minnesota, Vol. 59, no. 9

- ^ Poundstone, William (2008) Gaming the Vote: Why Elections Aren't Fair (and What We Can Do About It), Hill and Young, p. 198

- ^ Duverger, Maurice (1954) Political Parties, Wiley ISBN 0-416-68320-7

- ^ Douglas W. Rae (1971) The Political Consequences of Electoral Laws, Yale University Press ISBN 0-300-01517-8

- ^ Rein Taagapera and Matthew S. Shugart (1989) Seats and Votes: The Effects and Determinants of Electoral Systems, Yale University Press

- ^ Ferdinand A. Hermens (1941) Democracy or Anarchy? A Study of Proportional Representation, University of Notre Dame.

- ^ Arend Lijphart (1994) Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-Seven Democracies, 1945–1990 Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-828054-8

- ^ Arend Lijphart (1985) "The Field of Electoral Systems Research: A Critical Survey" Electoral Studies, Vol. 4

- ^ Arend Lijphart (1992) "Democratization and Constitutional Choices in Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, 1989–1991" Journal of Theoretical Politics Vol. 4 (2), pp. 207–223

- ^ Stein Rokkan (1970) Citizens, Elections, Parties: Approaches to the Comparative Study of the Process of Development, Universitetsforlaget

- ^ Ronald Rogowski (1987) "Trade and the Variety of Democratic Institutions", International Organization Vol. 41, pp. 203–24

- ^ Carles Boix (1999) "Setting the Rules of the Game: The Choice of Electoral Systems in Advanced Democracies", American Political Science Review Vol. 93 (3), pp. 609–624

- ^ "STV Information". Department of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 December 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "St. Louis, Missouri, Proposition D, Approval Voting Initiative (November 2020)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Cerrone, Joseph; McClintock, Cynthia (August 2023). "Come-from-behind victories under ranked-choice voting and runoff: The impact on voter satisfaction". Politics & Policy. 51 (4): 569–587. doi:10.1111/polp.12544. ISSN 1555-5623.

- ^ "First Past the Post to be introduced for all local mayoral and police and crime commissioner elections". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jason. "Missouri joins other red states in trying to stamp out ranked choice voting". NPR.

- ^ "Results for ranked-choice voting (RCV) and electoral system ballot measures, 2024". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2025-04-11.

- ^ Lijphart, Arend (March 1997). "Unequal Participation: Democracy's Unresolved Dilemma". American Political Science Review. 91 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/2952255. JSTOR 2952255. S2CID 143172061.

- ^ Blais, Andre (1990). "Does proportional representation foster voter turnout?". European Journal of Political Research. 18 (2): 167–181. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1990.tb00227.x.

- ^ Tullock, Gordon (1965). "Entry Barriers in Politics". The American Economic Review. 55 (1/2): 458–466. JSTOR 1816288. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Persson, T.; Tabellini, G. (2003). "Do Electoral Cycles Differ Across Political Systems?". Working Papers 232, IGIER (Innocenzo Gasparini Institute for Economic Research), Bocconi University. doi:10.2139/ssrn.392643. S2CID 5357676.

- ^ Cazals, A.; Mandon, P. (2019). "Political Budget Cycles: Manipulation by Leaders versus Manipulation by Researchers? Evidence from a Meta-Regression Analysis". Journal of Economic Surveys. 33 (1): 274–308. doi:10.1111/joes.12263. S2CID 158322229.

- ^ Bowler, Shaun; Farrell, David M.; Pettit, Robin T. (2005-04-01). "Expert opinion on electoral systems: So which electoral system is "best"?". Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 15 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1080/13689880500064544. ISSN 1745-7289. S2CID 144919388.