Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Twelve-tone technique

View on Wikipedia

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition. The technique is a means of ensuring that all 12 notes of the chromatic scale are sounded equally often in a piece of music while preventing the emphasis of any one note[3] through the use of tone rows, orderings of the 12 pitch classes. All 12 notes are thus given more or less equal importance, and the music avoids being in a key.

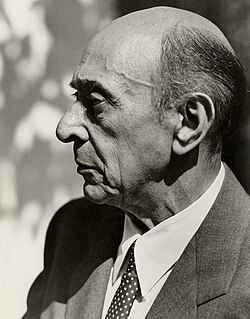

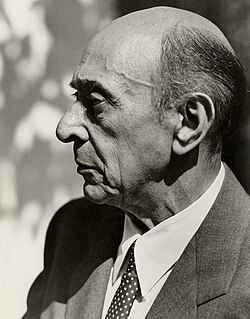

The technique was first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer,[not verified in body] who published his "law of the twelve tones" in 1919. In 1923, Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) developed his own, better-known version of 12-tone technique, which became associated with the "Second Viennese School" composers, who were the primary users of the technique in the first decades of its existence. Over time, the technique increased greatly in popularity and eventually became widely influential on mid-20th-century composers. Many important composers who had originally not subscribed to or actively opposed the technique, such as Aaron Copland and Igor Stravinsky,[clarification needed] eventually adopted it in their music.

Schoenberg himself described the system as a "Method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with one another".[4] It is commonly considered a form of serialism.

Schoenberg's fellow countryman and contemporary Hauer also developed a similar system using unordered hexachords or tropes—independent of Schoenberg's development of the twelve-tone technique. Other composers have created systematic use of the chromatic scale, but Schoenberg's method is considered to be most historically and aesthetically significant.[5]

History of use

[edit]The twelve-tone technique is most often attributed to Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg. He recalls using it in 1921 and describing it to pupils two years later.[8] Simultaneously, Josef Matthias Hauer was formulating a similar theory in his writings. In the second edition of his book Vom Wesen Des Musikalischen (On the Essence of Music, 1923), Hauer wrote that the law of the atonal melody requires all twelve tones to be played repeatedly.[9]

The method was used during the next twenty years almost exclusively by the composers of the Second Viennese School—Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Schoenberg himself. Although, another important composer in this period was Elisabeth Lutyens who wrote more than 50 pieces using the serial method.[10]

The twelve tone technique was preceded by "freely" atonal pieces of 1908–1923 which, though "free", often have as an "integrative element ... a minute intervallic cell" which in addition to expansion may be transformed as with a tone row, and in which individual notes may "function as pivotal elements, to permit overlapping statements of a basic cell or the linking of two or more basic cells".[11] The twelve-tone technique was also preceded by "nondodecaphonic serial composition" used independently in the works of Alexander Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, Béla Bartók, Carl Ruggles, and others.[12] Oliver Neighbour argues that Bartók was "the first composer to use a group of twelve notes consciously for a structural purpose", in 1908 with the third of his fourteen bagatelles.[13] "Essentially, Schoenberg and Hauer systematized and defined for their own dodecaphonic purposes a pervasive technical feature of 'modern' musical practice, the ostinato".[12] Additionally, John Covach argues that the strict distinction between the two, emphasized by authors including Perle, is overemphasized:

The distinction often made between Hauer and the Schoenberg school—that the former's music is based on unordered hexachords while the latter's is based on an ordered series—is false: while he did write pieces that could be thought of as "trope pieces", much of Hauer's twelve-tone music employs an ordered series.[14]

The "strict ordering" of the Second Viennese school, on the other hand, "was inevitably tempered by practical considerations: they worked on the basis of an interaction between ordered and unordered pitch collections."[15]

Rudolph Reti, an early proponent, says: "To replace one structural force (tonality) by another (increased thematic oneness) is indeed the fundamental idea behind the twelve-tone technique", arguing it arose out of Schoenberg's frustrations with free atonality,[16][page needed] providing a "positive premise" for atonality.[3] In Hauer's breakthrough piece Nomos, Op. 19 (1919) he used twelve-tone sections to mark out large formal divisions, such as with the opening five statements of the same twelve-tone series, stated in groups of five notes making twelve five-note phrases.[15]

Felix Khuner contrasted Hauer's more mathematical concept with Schoenberg's more musical approach.[17] Schoenberg's idea in developing the technique was for it to "replace those structural differentiations provided formerly by tonal harmonies".[4] As such, twelve-tone music is usually atonal, and treats each of the 12 semitones of the chromatic scale with equal importance, as opposed to earlier classical music which had treated some notes as more important than others (particularly the tonic and the dominant note).

The technique became widely used by the fifties, taken up by composers such as Milton Babbitt, Luciano Berio, Pierre Boulez, Luigi Dallapiccola, Ernst Krenek, Riccardo Malipiero, and, after Schoenberg's death, Igor Stravinsky. Some of these composers extended the technique to control aspects other than the pitches of notes (such as duration, method of attack and so on), thus producing serial music. Some even subjected all elements of music to the serial process.

Charles Wuorinen said in a 1962 interview that while "most of the Europeans say that they have 'gone beyond' and 'exhausted' the twelve-tone system", in America, "the twelve-tone system has been carefully studied and generalized into an edifice more impressive than any hitherto known."[18]

American composer Scott Bradley, best known for his musical scores for works like Tom & Jerry and Droopy Dog, utilized the 12-tone technique in his work. Bradley described his use thus:

The Twelve-Tone System provides the 'out-of-this-world' progressions so necessary to under-write the fantastic and incredible situations which present-day cartoons contain.[19]

An example of Bradley's use of the technique to convey building tension occurs in the Tom & Jerry short "Puttin' on the Dog", from 1944. In a scene where the mouse, wearing a dog mask, runs across a yard of dogs "in disguise", a chromatic scale represents both the mouse's movements, and the approach of a suspicious dog, mirrored octaves lower.[20] Apart from his work in cartoon scores, Bradley also composed tone poems that were performed in concert in California.[21]

Rock guitarist Ron Jarzombek used a twelve-tone system for composing Blotted Science's extended play The Animation of Entomology. He put the notes into a clock and rearranged them to be used that are side by side or consecutive. He called his method "Twelve-Tone in Fragmented Rows."[22]

Tone row

[edit]The basis of the twelve-tone technique is the tone row, an ordered arrangement of the twelve notes of the chromatic scale (the twelve equal tempered pitch classes). There are four postulates or preconditions to the technique which apply to the row (also called a set or series), on which a work or section is based:[23]

- The row is a specific ordering of all twelve notes of the chromatic scale (without regard to octave placement).

- No note is repeated within the row.

- The row may be subjected to interval-preserving transformations—that is, it may appear in inversion (denoted I), retrograde (R), or retrograde-inversion (RI), in addition to its "original" or prime form (P).

- The row in any of its four transformations may begin on any degree of the chromatic scale; in other words it may be freely transposed. (Transposition being an interval-preserving transformation, this is technically covered already by 3.) Transpositions are indicated by an integer between 0 and 11 denoting the number of semitones: thus, if the original form of the row is denoted P0, then P1 denotes its transposition upward by one semitone (similarly I1 is an upward transposition of the inverted form, R1 of the retrograde form, and RI1 of the retrograde-inverted form).

(In Hauer's system postulate 3 does not apply.)[2]

A particular transformation (prime, inversion, retrograde, retrograde-inversion) together with a choice of transpositional level is referred to as a set form or row form. Every row thus has up to 48 different row forms. (Some rows have fewer due to symmetry; see the sections on derived rows and invariance below.)

Example

[edit]Suppose the prime form of the row is as follows:

Then the retrograde is the prime form in reverse order:

The inversion is the prime form with the intervals inverted (so that a rising minor third becomes a falling minor third, or equivalently, a rising major sixth):

And the retrograde inversion is the inverted row in retrograde:

P, R, I and RI can each be started on any of the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, meaning that 47 permutations of the initial tone row can be used, giving a maximum of 48 possible tone rows. However, not all prime series will yield so many variations because transposed transformations may be identical to each other. This is known as invariance. A simple case is the ascending chromatic scale, the retrograde inversion of which is identical to the prime form, and the retrograde of which is identical to the inversion (thus, only 24 forms of this tone row are available).

In the above example, as is typical, the retrograde inversion contains three points where the sequence of two pitches are identical to the prime row. Thus the generative power of even the most basic transformations is both unpredictable and inevitable. Motivic development can be driven by such internal consistency.

Application in composition

[edit]Note that rules 1–4 above apply to the construction of the row itself, and not to the interpretation of the row in the composition. (Thus, for example, postulate 2 does not mean, contrary to common belief, that no note in a twelve-tone work can be repeated until all twelve have been sounded.) While a row may be expressed literally on the surface as thematic material, it need not be, and may instead govern the pitch structure of the work in more abstract ways. Even when the technique is applied in the most literal manner, with a piece consisting of a sequence of statements of row forms, these statements may appear consecutively, simultaneously, or may overlap, giving rise to harmony.

Durations, dynamics and other aspects of music other than the pitch can be freely chosen by the composer, and there are also no general rules about which tone rows should be used at which time (beyond their all being derived from the prime series, as already explained). However, individual composers have constructed more detailed systems in which matters such as these are also governed by systematic rules (see serialism).

Topography

[edit]Analyst Kathryn Bailey has used the term 'topography' to describe the particular way in which the notes of a row are disposed in her work on the dodecaphonic music of Webern. She identifies two types of topography in Webern's music: block topography and linear topography.

The former, which she views as the 'simplest', is defined as follows: 'rows are set one after the other, with all notes sounding in the order prescribed by this succession of rows, regardless of texture'. The latter is more complex: the musical texture 'is the product of several rows progressing simultaneously in as many voices' (note that these 'voices' are not necessarily restricted to individual instruments and therefore cut across the musical texture, operating as more of a background structure).[25]

Elisions, Chains, and Cycles

[edit]Serial rows can be connected through elision, a term that describes 'the overlapping of two rows that occur in succession, so that one or more notes at the juncture are shared (are played only once to serve both rows)'.[26] When this elision incorporates two or more notes it creates a row chain;[27] when multiple rows are connected by the same elision (typically identified as the same in set-class terms) this creates a row chain cycle, which therefore provides a technique for organising groups of rows.[28]

Properties of transformations

[edit]The tone row chosen as the basis of the piece is called the prime series (P). Untransposed, it is notated as P0. Given the twelve pitch classes of the chromatic scale, there are 12 factorial[29] (479,001,600[15]) tone rows, although this is far higher than the number of unique tone rows (after taking transformations into account). There are 9,985,920 classes of twelve-tone rows up to equivalence (where two rows are equivalent if one is a transformation of the other).[30]

Appearances of P can be transformed from the original in three basic ways:

- transposition up or down, giving Pχ.

- reversing the order of the pitches, giving the retrograde (R)

- turning each interval direction to its opposite, giving the inversion (I).

The various transformations can be combined. These give rise to a set-complex of forty-eight forms of the set, 12 transpositions of the four basic forms: P, R, I, RI. The combination of the retrograde and inversion transformations is known as the retrograde inversion (RI).

RI is: RI of P, R of I, and I of R. R is: R of P, RI of I, and I of RI. I is: I of P, RI of R, and R of RI. P is: R of R, I of I, and RI of RI.

thus, each cell in the following table lists the result of the transformations, a four-group, in its row and column headers:

P: RI: R: I: RI: P I R R: I P RI I: R RI P

However, there are only a few numbers by which one may multiply a row and still end up with twelve tones. (Multiplication is in any case not interval-preserving.)

Derivation

[edit]Derivation is transforming segments of the full chromatic, fewer than 12 pitch classes, to yield a complete set, most commonly using trichords, tetrachords, and hexachords. A derived set can be generated by choosing appropriate transformations of any trichord except 0,3,6, the diminished triad[citation needed]. A derived set can also be generated from any tetrachord that excludes the interval class 4, a major third, between any two elements. The opposite, partitioning, uses methods to create segments from sets, most often through registral difference.

Combinatoriality

[edit]Combinatoriality is a side-effect of derived rows where combining different segments or sets such that the pitch class content of the result fulfills certain criteria, usually the combination of hexachords which complete the full chromatic.

Invariance

[edit]Invariant formations are also the side effect of derived rows where a segment of a set remains similar or the same under transformation. These may be used as "pivots" between set forms, sometimes used by Anton Webern and Arnold Schoenberg.[32]

Invariance is defined as the "properties of a set that are preserved under [any given] operation, as well as those relationships between a set and the so-operationally transformed set that inhere in the operation",[33] a definition very close to that of mathematical invariance. George Perle describes their use as "pivots" or non-tonal ways of emphasizing certain pitches. Invariant rows are also combinatorial and derived.

Cross partition

[edit]

A cross partition is an often monophonic or homophonic technique which, "arranges the pitch classes of an aggregate (or a row) into a rectangular design", in which the vertical columns (harmonies) of the rectangle are derived from the adjacent segments of the row and the horizontal columns (melodies) are not (and thus may contain non-adjacencies).[35]

For example, the layout of all possible 'even' cross partitions is as follows:[36]

62 43 34 26 ** *** **** ****** ** *** **** ****** ** *** **** ** *** ** **

One possible realization out of many for the order numbers of the 34 cross partition, and one variation of that, are:[36]

0 3 6 9 0 5 6 e 1 4 7 t 2 3 7 t 2 5 8 e 1 4 8 9

Thus if one's tone row was 0 e 7 4 2 9 3 8 t 1 5 6, one's cross partitions from above would be:

0 4 3 1 0 9 3 6 e 2 8 5 7 4 8 5 7 9 t 6 e 2 t 1

Cross partitions are used in Schoenberg's Op. 33a Klavierstück and also by Berg but Dallapicolla used them more than any other composer.[37]

Other

[edit]In practice, the "rules" of twelve-tone technique have been bent and broken many times, not least by Schoenberg himself. For instance, in some pieces two or more tone rows may be heard progressing at once, or there may be parts of a composition which are written freely, without recourse to the twelve-tone technique at all. Offshoots or variations may produce music in which:

- the full chromatic is used and constantly circulates, but permutational devices are ignored

- permutational devices are used but not on the full chromatic

Also, some composers, including Stravinsky, have used cyclic permutation, or rotation, where the row is taken in order but using a different starting note. Stravinsky also preferred the inverse-retrograde, rather than the retrograde-inverse, treating the former as the compositionally predominant, "untransposed" form.[38]

Although usually atonal, twelve tone music need not be—several pieces by Berg, for instance, have tonal elements.

One of the best known twelve-note compositions is Variations for Orchestra by Arnold Schoenberg. "Quiet", in Leonard Bernstein's Candide, satirizes the method by using it for a song about boredom, and Benjamin Britten used a twelve-tone row—a "tema seriale con fuga"—in his Cantata Academica: Carmen Basiliense (1959) as an emblem of academicism.[39]

Schoenberg's mature practice

[edit]Ten features of Schoenberg's mature twelve-tone practice are characteristic, interdependent, and interactive:[40]

- Hexachordal inversional combinatoriality

- Aggregates

- Linear set presentation

- Partitioning

- Isomorphic partitioning

- Invariants

- Hexachordal levels

- Harmony, "consistent with and derived from the properties of the referential set"

- Metre, established through "pitch-relational characteristics"

- Multidimensional set presentations.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Whittall 2008, 26.

- ^ a b Perle 1991, 145.

- ^ a b Perle 1977, 2.

- ^ a b Schoenberg 1975, 218.

- ^ Whittall 2008, 25.

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 149.

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 155–157.

- ^ Schoenberg 1975, 213.

- ^ Hauer, Josef Matthias, 1883-1959. Vom Wesen Des Musikalischen: Ein Lehrbuch Der Zwölftöne-musik. Berlin-Lichterfelde: Schlesinger (R. Lienau), 1923. 51.

- ^ "Elisabeth Lutyens". The Musical Times. 124 (1684): 378. 1983. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 964096.

- ^ Perle 1977, 9–10.

- ^ a b Perle 1977, 37.

- ^ Neighbour 1955, 53.

- ^ John Covach quoted in Whittall 2008, 24.

- ^ a b c Whittall 2008, 24.

- ^ Reti 1958

- ^ Crawford and Khuner 1996, 28.

- ^ Chase 1987, 587.

- ^ Yowp (7 January 2017). "Tralfaz: Cartoon Composer Scott Bradley".

- ^ Goldmark, Daniel (2007). Tunes for 'Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon. Univ of California Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-520-25311-7.

- ^ Scott Bradley at IMDb

- ^ Mustein, Dave (2 November 2011). "Blotted Science's Ron Jarzombek: The Twelve-tone Metalsucks Interview". MetalSucks. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Perle 1977, 3.

- ^ Whittall 2008, 52.

- ^ Bailey, Kathryn (2006). The twelve-note music of Anton Webern: old forms in a new language. Music in the twentieth century (Digitally printed 1st pbk. version ed.). Cambridge [England] New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-39088-0.

- ^ Bailey, Kathryn (2006). The twelve-note music of Anton Webern: old forms in a new language. Music in the twentieth century (Digitally printed 1st pbk. version ed.). Cambridge [England] New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-521-39088-0.

- ^ Moseley, Brian (1 September 2019). "Transformation Chains, Associative Areas, and a Principle of Form for Anton Webern's Twelve-tone Music". Music Theory Spectrum. 41 (2): 218–243. doi:10.1093/mts/mtz010. ISSN 0195-6167.

- ^ Moseley, Brian (2018). "Cycles in Webern's Late Music". Journal of Music Theory. 62 (2): 165–204. doi:10.1215/00222909-7127658. ISSN 0022-2909. S2CID 171497028.

- ^ Loy 2007, 310.

- ^ Benson 2007, 348.

- ^ Haimo 1990, 27.

- ^ Perle 1977, 91–93.

- ^ Babbitt 1960, 249–250.

- ^ Haimo 1990, 13.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 20.

- ^ a b Alegant 2010, 21.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 22, 24.

- ^ Spies 1965, 118.

- ^ Brett 2007.

- ^ Haimo 1990, 41.

Sources

[edit]- Alegant, Brian. 2010. The Twelve-Tone Music of Luigi Dallapiccola. Eastman Studies in Music 76. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-325-6.

- Babbitt, Milton. 1960. "Twelve-Tone Invariants as Compositional Determinants". The Musical Quarterly 46, no. 2, Special Issue: Problems of Modern Music: The Princeton Seminar in Advanced Musical Studies (April): 246–259. doi:10.1093/mq/XLVI.2.246. JSTOR 740374(subscription required).

- Babbitt, Milton. 1961. "Set Structure as a Compositional Determinant". Journal of Music Theory 5, no. 1 (Spring): 72–94. JSTOR 842871(subscription required).

- Benson, Dave. 2007 Music: A Mathematical Offering. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85387-3.

- Brett, Philip. "Britten, Benjamin." Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 8 January 2007)

- Chase, Gilbert. 1987. America's Music: From the Pilgrims to the Present, revised third edition. Music in American Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00454-X (cloth); ISBN 0-252-06275-2 (pbk).

- Crawford, Caroline and Felix Khuner. 1996. Felix Khuner: A Violinist's Journey from Vienna's Kolisch Quartet to the San Francisco Symphony and Opera Orchestras, intro. by Tom Heimberg. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library. Berkeley: University of California.

- Haimo, Ethan. 1990. Schoenberg's Serial Odyssey: The Evolution of his Twelve-Tone Method, 1914–1928. Oxford [England] Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-315260-6.

- Hill, Richard S. 1936. "Schoenberg's Tone-Rows and the Tonal System of the Future". The Musical Quarterly 22, no. 1 (January): 14–37. doi:10.1093/mq/XXII.1.14. JSTOR 739013(subscription required).

- Lansky, Paul; George Perle and Dave Headlam. 2001. "Twelve-note Composition". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan.

- Leeuw, Ton de. 2005. Music of the Twentieth Century: A Study of Its Elements and Structure, translated from the Dutch by Stephen Taylor. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-765-8. Translation of Muziek van de twintigste eeuw: een onderzoek naar haar elementen en structuur. Utrecht: Oosthoek, 1964. Third impression, Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema, 1977. ISBN 90-313-0244-9.

- Loy, D. Gareth, 2007. Musimathics: The Mathematical Foundations of Music, Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-12282-5.

- Neighbour, Oliver. 1954. "The Evolution of Twelve-Note Music". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, volume 81, issue 1: 49–61. doi:10.1093/jrma/81.1.49

- Perle, George. 1977. Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, fourth edition, revised. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03395-7

- Perle, George. 1991. Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, sixth edition, revised. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07430-9.

- Reti, Rudolph. 1958. Tonality, Atonality, Pantonality: A Study of Some Trends in Twentieth Century Music. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-20478-0.

- Rufer, Josef. 1954. Composition with Twelve Notes Related Only to One Another, translated by Humphrey Searle. New York: The Macmillan Company. (Original German ed., 1952)

- Schoenberg, Arnold. 1975. Style and Idea, edited by Leonard Stein with translations by Leo Black. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05294-3.

- 207–208 "Twelve-Tone Composition (1923)"

- 214–245 "Composition with Twelve Tones (1) (1941)"

- 245–249 "Composition with Twelve Tones (2) (c. 1948)"

- Solomon, Larry. 1973. "New Symmetric Transformations". Perspectives of New Music 11, no. 2 (Spring–Summer): 257–264. JSTOR 832323(subscription required).

- Spies, Claudio. 1965. "Notes on Stravinsky's Abraham and Isaac". Perspectives of New Music 3, no. 2 (Spring–Summer): 104–126. JSTOR 832508(subscription required).

- Whittall, Arnold. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Serialism. Cambridge Introductions to Music. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86341-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-521-68200-8 (pbk).

Further reading

[edit]- Covach, John. 1992. "The Zwölftonspiel of Josef Matthias Hauer". Journal of Music Theory 36, no. 1 (Spring): 149–84. JSTOR 843913(subscription required).

- Covach, John. 2000. "Schoenberg's 'Poetics of Music', the Twelve-tone Method, and the Musical Idea". In Schoenberg and Words: The Modernist Years, edited by Russell A. Berman and Charlotte M. Cross, New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-2830-3

- Covach, John. 2002, "Twelve-tone Theory". In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, edited by Thomas Christensen, 603–627. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62371-5.

- Krenek, Ernst. 1953. "Is the Twelve-Tone Technique on the Decline?" The Musical Quarterly 39, no 4 (October): 513–527.

- Šedivý, Dominik. 2011. Serial Composition and Tonality. An Introduction to the Music of Hauer and Steinbauer, edited by Günther Friesinger, Helmut Neumann and Dominik Šedivý. Vienna: edition mono. ISBN 3-902796-03-0

- Sloan, Susan L. 1989. "Archival Exhibit: Schoenberg's Dodecaphonic Devices". Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Institute 12, no. 2 (November): 202–205.

- Starr, Daniel. 1978. "Sets, Invariance and Partitions". Journal of Music Theory 22, no. 1 (Spring): 1–42. JSTOR 843626(subscription required).

- Wuorinen, Charles. 1979. Simple Composition. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-28059-1. Reprinted 1991, New York: C. F. Peters. ISBN 0-938856-06-5.

External links

[edit]- Twelve tone square to find all combinations of a 12 tone sequence

- New Transformations: Beyond P, I, R, and RI by Larry Solomon

- Javascript twelve tone matrix calculator and tone row analyzer

- Matrix generator from musictheory.net by Ricci Adams

- Twelve-Tone Technique, A Quick Reference by Dan Román

- Twelve Tones by mathemusician Vi Hart on YouTube

- Dodecaphonic Knots and Topology of Words by Franck Jedrzejewski

- Database on tone rows and tropes

Twelve-tone technique

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Development

Invention and Early Concepts

Arnold Schoenberg, having pioneered free atonality in works from around 1908 to the early 1920s, grew dissatisfied with its improvisatory nature and lack of systematic unity, prompting him to seek a compositional method that would ensure the equal treatment of all twelve chromatic pitches without favoring any tonal center.[7] This motivation stemmed from his desire to extend the emancipation of dissonance while restoring structural coherence akin to traditional tonality, but grounded in pitch-class equality rather than key-based hierarchy.[8] Early explorations of these ideas appear in Schoenberg's private sketches dating from 1915 to 1917, including a twelve-tone theme in the Scherzo of his unfinished symphony from that period, marking initial steps toward serial organization.[8] These sketches reflect tentative efforts to array pitches in sequences that avoided repetition and tonal bias, though they remained unpublished and undeveloped at the time.[3] The technique's core development occurred between 1920 and 1923, during which Schoenberg was influenced by Josef Matthias Hauer's concurrent work on twelve-tone composition, particularly Hauer's Von der Melodie (1919) and his tropoi—unordered sets of six pitches forming the basis of atonal structures—but Schoenberg differentiated his approach by emphasizing strictly ordered rows to govern melodic and harmonic content.[9] This period culminated in the formalization of the method in Schoenberg's Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 (1923), where the third piece, "Walzer," employs a single twelve-tone row as its foundational unit to serialize pitch classes and eliminate tonal implications.[8] The core principle of this serialization ensures that all twelve pitches relate solely to one another within the row, preventing any subset from suggesting traditional harmony or key.[7]Evolution in Schoenberg's Works

Schoenberg's compositional approach evolved from the free atonality of his earlier works, such as Pierrot Lunaire (1912), which eschewed traditional tonal centers without a systematic organizing principle, toward a more structured serialism by the early 1920s. This transition culminated in the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1921–1923), recognized as his first fully twelve-tone composition, where he introduced systematic row transpositions and emphasized the equality of all twelve pitches while integrating neoclassical forms like prelude, minuet, and gigue. In this suite, Schoenberg balanced the method's rigor with expressive elements, such as rhythmic and registral variations that projected row forms, marking a shift from the improvisatory atonality of pieces like the Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909) to a disciplined framework that ensured motivic coherence across movements.[8][10] Key milestones in this evolution include the Wind Quintet, Op. 26 (1924), Schoenberg's first multi-instrumental twelve-tone work for chamber ensemble, which fully realized the method by employing the row and its inversion to generate thematic material and contrapuntal textures. Composed for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn, it revived classical forms such as sonata and rondo, demonstrating the technique's adaptability to larger-scale structures and instrumental interplay, while avoiding orchestral forces. Later, in the opera Moses und Aron (begun 1930), Schoenberg applied varied row partitions and hexachordal combinations to dramatize thematic conflicts, such as the tension between divine idea and human representation, further refining the method's capacity for narrative depth. These works illustrate Schoenberg's progressive integration of serial procedures into diverse genres, from solo piano to vocal-orchestral forms.[8][11][12] Throughout this period, Schoenberg grappled with balancing the method's strict serial organization against musical expressivity, occasionally incorporating tonal allusions—such as triadic formations or cadential gestures—to evoke emotional resonance without undermining the row's primacy. He articulated this tension in reflections emphasizing that "everything of supreme value in art must show heart as well as brain," underscoring the need for subconscious inspiration to guide technical control. His appointment as professor of composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts (1925–1933) played a pivotal role in formalizing the technique, as he taught advanced composition to students like Winfried Zillig and Hanns Eisler, refining its principles through pedagogical exposition and application in classroom analyses. This institutional context helped solidify the method as a teachable system, influencing its dissemination before his dismissal in 1933 amid political upheaval.[8]Adoption by Other Composers

Alban Berg, one of Schoenberg's closest pupils, was among the first to adapt the twelve-tone technique in a more lyrical and expressive manner, as seen in his Lyric Suite for string quartet (1926), where serial procedures coexist with tonal allusions and emotional depth to evoke personal narrative.[13] In this work, Berg selectively applied twelve-tone rows to certain movements while allowing freer, tonally inflected passages elsewhere, creating a hybrid that bridged atonal innovation with Romantic sensibility.[14] Berg extended this approach in his Violin Concerto (1936), his final completed composition, which integrates a twelve-tone row derived from folk tunes and Bach chorales with overt tonal structures, resulting in a memorial work that balances serial rigor and melodic warmth.[15] Anton Webern, another key figure in Schoenberg's circle, embraced the twelve-tone method with an emphasis on structural economy and timbral innovation, particularly in his Symphony, Op. 21 (1928), the first fully serial orchestral piece by any of Schoenberg's students.[16] Here, Webern employed a palindromic tone row to achieve maximal symmetry and concision, using brief motifs and Klangfarbenmelodie—melody defined by shifting timbres rather than pitch alone—to distribute notes across instruments in sparse, pointillistic textures that heightened the work's austerity and precision.[17] Hanns Eisler incorporated the technique into politically charged compositions during the 1930s, adapting it to convey socialist ideals amid rising fascism.[18] In pieces like the Deutsche Sinfonie (begun 1935), Eisler combined serial rows with agitprop elements, such as Brechtian texts and march-like rhythms, to critique capitalism and war while maintaining accessibility for mass audiences.[19] This fusion reflected Eisler's belief that twelve-tone could serve revolutionary purposes without sacrificing ideological clarity. The Nazi regime's classification of twelve-tone music as "degenerate art" led to severe suppression from 1933 onward, with performances banned, scores confiscated, and composers like Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, and Eisler forced into exile or silence, compelling the technique's dissemination through clandestine networks and émigré communities in the United States and elsewhere.[20] After World War II, René Leibowitz emerged as a leading advocate in France, promoting the method through his 1947 treatise Introduction à la musique de douze sons and conducting premieres of Second Viennese School works, which helped establish serialism as a cornerstone of postwar European composition.[21] Leibowitz's efforts, including teaching figures like Boulez, countered lingering resistance and fostered a rigorous theoretical framework for the technique's broader adoption.[22]Fundamentals of the Tone Row

Definition and Basic Construction

The twelve-tone technique is a method of musical composition in which the twelve pitch classes of the chromatic scale are arranged into a specific ordered sequence known as a tone row, serving as the foundational source for all pitches in the work. This approach, developed by Arnold Schoenberg in the early 1920s, ensures that each pitch class appears exactly once in the row before any repetition occurs, thereby generating the entire pitch content systematically.[23][24] The construction of a tone row involves the composer selecting an arbitrary ordering of the twelve distinct pitch classes, typically designed to eschew immediate patterns reminiscent of traditional tonality, such as triads or scalar progressions, in order to preserve an atonal framework. No pitch class is repeated until all others have been stated, though exceptions like immediate repetitions for emphasis or in ornamental figures such as trills are permitted. Pitch classes are commonly notated using integers from 0 to 11 in modulo 12 arithmetic, with 0 representing C, 1 for C♯/D♭, and so forth; a representative prime row starting on 0, for instance, might be expressed as 0, 1, 4, 6, 8, 10, 7, 9, 5, 11, 3, 2.[2][23][25] By mandating the equal utilization of all pitch classes without privileging any as a tonic, the tone row promotes the equality of tones and facilitates the emancipation of dissonance, wherein dissonance is no longer subordinated to consonance but integrated as a structural equal within the composition. This contrasts with tonal music's hierarchical organization and aligns with broader atonal principles by emphasizing intervallic relationships over chordal or scalar functions.[24][26] Notationally, a tone row is an ordered sequence, distinct from an unordered pitch-class set, which collects pitch classes without regard to sequence, and from scales, which cyclically repeat and imply a tonal center for resolution. This ordered structure underscores the row's role in providing motivic and structural unity across the piece.[2][25]Standard Example of a Tone Row

A canonical illustration of a tone row appears in Arnold Schoenberg's Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1921–1923), one of the composer's earliest fully twelve-tone works. The prime form of the row, designated P₄ in standard integer notation (with C as 0), consists of the pitch classes 4, 5, 7, 1, 6, 3, 8, 2, 11, 0, 9, 10, corresponding to the pitches E–F–G–D♭–G♭–E♭–A♭–D–B–C–A–B♭.[27] This sequence encompasses all twelve chromatic pitches without repetition, structured as three tetrachords: [E–F–G–D♭], [G♭–E♭–A♭–D], and [B–C–A–B♭].[28] In integer form for analytical purposes: In the Präludium (first movement), the row is stated linearly in the right hand within a three-voice polyphonic texture, with the opening measures 1–3 unfolding the row across the upper voice in three tetrachords: the first (E–F–G–D♭) in measures 1–2, the second (G♭–E♭–A♭–D) continuing in measures 2–3, and the third (B–C–A–B♭) completing in measure 3. This full prime row extends through measures 1–19, interwoven with complementary voices to form complete chromatic aggregates, demonstrating the row's role as a unifying melodic motif.[28][10] To highlight the row's intervallic structure, the directed semitone intervals between adjacent pitches (positive for ascending, negative for descending) provide insight into its rhythmic and motivic potential:| Transition | From Pitch Class | To Pitch Class | Interval (semitones) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 4 (E) | 5 (F) | +1 |

| 2–3 | 5 (F) | 7 (G) | +2 |

| 3–4 | 7 (G) | 1 (D♭) | -6 |

| 4–5 | 1 (D♭) | 6 (G♭) | +5 |

| 5–6 | 6 (G♭) | 3 (E♭) | -3 |

| 6–7 | 3 (E♭) | 8 (A♭) | +5 |

| 7–8 | 8 (A♭) | 2 (D) | -6 |

| 8–9 | 2 (D) | 11 (B) | +9 |

| 9–10 | 11 (B) | 0 (C) | -11 |

| 10–11 | 0 (C) | 9 (A) | +9 |

| 11–12 | 9 (A) | 10 (B♭) | +1 |

Row Forms and Their Notation

In twelve-tone technique, a single tone row serves as the basis for generating a complete family of related forms through specific operations, ensuring comprehensive utilization of the chromatic pitch classes. These operations produce four primary row forms: the prime form (P), which is the original sequence of twelve pitch classes; the inversion (I), created by inverting the intervals of the prime form around its initial pitch class (such that ascending intervals become descending and vice versa, preserving interval sizes); the retrograde (R), obtained by reversing the order of the prime form; and the retrograde-inversion (RI), which applies inversion to the retrograde or, equivalently, retrograde to the inversion. Each of these four forms can be transposed to any of the twelve possible starting pitch classes within the chromatic scale, yielding a total of 48 distinct row forms for a given tone row (12 transpositions multiplied by 4 operations). Transpositions are typically indexed by a subscript numeral from 0 to 11, corresponding to semitone displacement from a reference pitch (often C=0); for instance, P_5 denotes the prime form transposed upward by five semitones, so that if the original P_0 begins on pitch class 0, P_5 begins on pitch class 5. This indexing applies analogously to the other forms, such as I_5 or R_3. However, if the tone row exhibits inherent symmetries—such as invariance under certain transpositions, inversions, or retrogrades—the number of unique forms may be reduced, as some operations yield equivalents of existing forms.[29][30] Standard notation for these forms, including the subscript indexing (e.g., I_n for the nth transposition of the inversion and RI_n for the retrograde-inversion), was systematized by composer-theorists like Milton Babbitt in his analyses of serial structures. Babbitt's approach emphasizes the relational properties among forms, using this notation to track invariant intervals and pitch-class sets across operations. Complementing this, George Perle developed the twelve-tone matrix (or row array), a tabular grid that visually organizes all 48 forms for analytical purposes: the left column lists the 12 transpositions of the prime form (P_0 to P_11), the top row lists the 12 transpositions of the inversion (I_0 to I_11), and each cell at the intersection of P_m and I_n contains the pitch sequence of the row form starting with the pitch class at that position, facilitating quick derivation of retrogrades and retrograde-inversions by reading rows backward or columns downward. This matrix, introduced in Perle's foundational text on serialism, enables composers and analysts to navigate the full array of forms efficiently without recalculating each one manually.[31][29]Serial Transformations and Operations

Prime Form and Its Properties

The prime form, denoted as P or P_n where n indicates the starting pitch class (0 to 11), represents the original, untransformed sequence of all twelve pitch classes arranged in a specific order, serving as the foundational generator for the entire serial structure in twelve-tone composition. This form establishes the basic linear ordering that ensures each pitch class appears exactly once, avoiding tonal hierarchy while providing a fixed succession for melodic and harmonic derivation.[2] The interval content of the prime form consists of the eleven directed intervals between consecutive pitch classes, calculated as the difference modulo 12 (ranging from 1 to 11), which defines the row's rhythmic and melodic profile. These intervals determine the row's character, such as its motivic gestures or potential for combinatorial properties when segmented. A special case is the all-interval series, where the eleven adjacent directed intervals comprise each value from 1 to 11 exactly once, maximizing intervallic variety and often resulting in a tritone (interval 6) between the first and last pitch classes due to the sum of 1 through 11 equaling 66, or 6 modulo 12.[32][33] Such rows, first systematically analyzed in the 1970s, appear in works like Alban Berg's Lyric Suite (1926), enhancing structural density.[32] Analytical examination of the prime form often involves segmentation into tetrachords (groups of four consecutive notes) or hexachords (groups of six), revealing invariant subsets or recurring interval patterns that contribute to coherence. For instance, tetrachordal division can highlight balanced interval distributions within segments, while hexachordal analysis uncovers potential for row overlap in multi-voice textures. The prime form fosters thematic unity by supplying the core intervallic and pitch successions that permeate the composition, allowing derived segments to echo its essential motives across sections. To illustrate interval content, consider the prime form P_3: [3, 5, 0, 7, 9, 1, 4, 6, 10, 8, 11, 2] (pitch classes modulo 12). The adjacent directed intervals are calculated as follows:| Position | From | To | Directed Interval (mod 12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 2-3 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| 3-4 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| 4-5 | 7 | 9 | 2 |

| 5-6 | 9 | 1 | 4 |

| 6-7 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| 7-8 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| 8-9 | 6 | 10 | 4 |

| 9-10 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 10-11 | 8 | 11 | 3 |

| 11-12 | 11 | 2 | 3 |

Inversion and Retrograde Operations

In the twelve-tone technique, inversion transforms the prime row by reflecting its intervals around an axis defined by the starting pitch, effectively reversing the direction of each successive interval while preserving their magnitudes modulo 12. This operation, one of the four basic row forms derived from the prime, ensures that the inverted row contains the same twelve pitch classes in a reordered sequence that mirrors the original's intervallic structure in the opposite direction. As Arnold Schoenberg described, the inversion is automatically derived from the basic set as a "mirror form" where ascending intervals become descending and vice versa.[7] The mathematical formulation for the inversion of a prime row , where is the starting pitch class (0 to 11), is given by for to . This formula inverts each position relative to the axis at , maintaining the row's integrity within the chromatic scale. A key property of inversion is the preservation of interval succession in magnitude but not direction; for instance, a +3 semitone interval becomes -3 (or +9 modulo 12), allowing the form to be transposed equivalently to the prime while altering melodic contours. This equivalence under transposition underscores inversion's role in generating variety without introducing tonal hierarchy. Retrograde, the second basic transformation, simply reverses the order of the prime row's pitches, starting from the original ending note and proceeding backward to the starting note. Denoted as , where designates the ending pitch class for consistency in notation (unlike the prime and inversion, which use the starting pitch), it is computed as . Schoenberg identified the retrograde as the basic set played in reverse, providing a straightforward way to derive motivic material that echoes but inverts the temporal flow of the original. Unlike inversion, retrograde reverses the sequence entirely, disrupting interval succession while retaining the pitch classes; it too maintains equivalence under transposition, enabling seamless integration across row forms.[7] These operations are exemplified in Schoenberg's Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1921–23), his first fully twelve-tone work, which employs a prime row beginning on E (pitch class 4): E–F–G–D♭–G♭–E♭–A♭–D–B–C–A–B♭, or in integers [4, 5, 7, 1, 6, 3, 8, 2, 11, 0, 9, 10]. The corresponding inversion yields [4, 3, 1, 7, 2, 5, 0, 6, 9, 8, 11, 10], or E–E♭–D♭–G–D–F–C–F♯–A–A♭–B–B♭, transforming upward leaps (e.g., the initial +1 and +2 semitones) into downward motions (-1 and -2) and altering the melodic contour from ascending to predominantly descending in the opening gestures. The retrograde , ending on 4, is the reverse: [10, 9, 0, 11, 2, 8, 3, 6, 1, 7, 5, 4], or B♭–A–C–B–D–A♭–E♭–G♭–D♭–G–F–E, which in the suite's Prelude (mm. 20–21) pairs with the prime to create palindromic dyads, emphasizing symmetry in texture. These transformations highlight how inversion and retrograde facilitate contour variation and structural balance without repeating pitches prematurely.[10]Retrograde-Inversion and Composite Forms

The retrograde-inversion (RI) represents a composite transformation in the twelve-tone technique, achieved by applying inversion to the prime row form followed by retrograde, or alternatively, by retrograding the prime and then inverting it. This operation preserves the intervallic content of the original row while reversing both the directional and sequential aspects, resulting in a form that mirrors the prime in a dual manner. In integer notation, where pitches are assigned numbers from 0 to 11, the pitch at position (with ranging from 1 to 12) in the retrograde-inversion transposed by is given by , ensuring modular arithmetic aligns the structure modulo 12.[5] This duality inherent in the retrograde-inversion—wherein RI is equivalently the inversion of the retrograde or the retrograde of the inversion—underpins the symmetrical architecture of the serial system, fostering balance between forward and backward motions as well as upward and downward interval trajectories. Such symmetry extends to the broader composite framework, where the four basic row forms (prime, retrograde, inversion, and retrograde-inversion), each subjected to 12 transpositions, generate a total of 48 distinct forms. These 48 forms constitute a closed group under the serial operations of transposition, inversion, and retrograde, forming a set of up to 48 distinct forms (the four basic forms each transposed to 12 pitch levels), which constitute a closed system under the serial operations of transposition, inversion, and retrograde, generating a group of order 48 for rows without symmetries.[34] In analytical terms, the composite properties of these forms enable sophisticated row overlaps in polyphonic contexts, where segments from different transformations (such as a prime in one voice overlapping with a retrograde-inversion in another) can interweave without pitch-class repetition, thereby supporting contrapuntal density while adhering to the non-replicative principle of twelve-tone organization. This capability is particularly evident in array-based progressions, where retrograde-inversions facilitate invariant interval cycles across voices, enhancing textural cohesion without compromising serial integrity.[35]Advanced Derivational Techniques

Combinatoriality in Hexachords

Combinatoriality in hexachords refers to a property of twelve-tone rows where specific transpositions of the prime form (P) and its inversion (I), or the retrograde (R) and retrograde-inversion (RI), share identical hexachordal content, allowing their simultaneous presentation to form aggregates that collectively span the entire chromatic scale without repetition.[31] This technique, which facilitates polyphonic textures by ensuring complementary pitch-class sets in the first and second hexachords (the initial and final six pitches of the row), was formalized by Milton Babbitt as a means to extend serial control beyond linear statements to vertical and contrapuntal combinations.[31] Rows exhibiting combinatoriality are classified by the transformations under which the hexachords align: semi-combinatorial rows satisfy the property for one pair of forms (such as P-I or R-RI), while all-combinatorial rows (AC) satisfy it for all four pairs (P-I, R-RI, P-RI, and R-I).[31] Only six distinct all-combinatorial row classes exist, each derived from one of the six all-combinatorial hexachords, which possess the necessary invariance under transposition, inversion, and retrograde to enable these alignments. Cyclic permutations of the hexachords within such rows can further enhance rotational symmetries, allowing flexible segmentation for contrapuntal deployment.[31] The condition for combinatoriality between the prime and a transposed inversion, such as P and I₅, requires set equality between the first hexachord of P and the transposed second hexachord of I:where and denote pitch classes modulo 12.[31] Similar equalities hold for the second hexachords under the complementary transposition, ensuring the combined forms produce two full aggregates. This hexachordal matching extends to other pairs, with the transposition interval (e.g., 5 for P-I in certain classes) determined by the row's interval structure. A prominent example is the all-combinatorial row from Anton Webern's Symphonie, Op. 21 (1928), given as P₀: A, F♯, G, A♭, E, F, B, B♭, D, C♯, C, E♭ (pitch classes: 9, 6, 7, 8, 4, 5, 11, 10, 2, 1, 0, 3). The row's hexachords are both instances of set class 6-1 (the chromatic hexachord of six consecutive pitch classes), enabling combinations like P₀ with I₅, where the first hexachord of P₀ matches the second hexachord of I₅, and vice versa, to form vertical aggregates in the work's canonic textures. This property allows Webern to overlap row forms in polyphony, such as the double canon in the second movement, creating dense yet controlled harmonic fields.[31]