Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Cubic surface.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cubic surface

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Cubic surface

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A cubic surface is a smooth projective hypersurface of degree three in three-dimensional projective space , defined over an algebraically closed field (typically the complex numbers) by a homogeneous polynomial equation of degree three.[1] These surfaces are fundamental objects in algebraic geometry, serving as the simplest nontrivial examples of algebraic surfaces beyond quadrics and planes.[1]

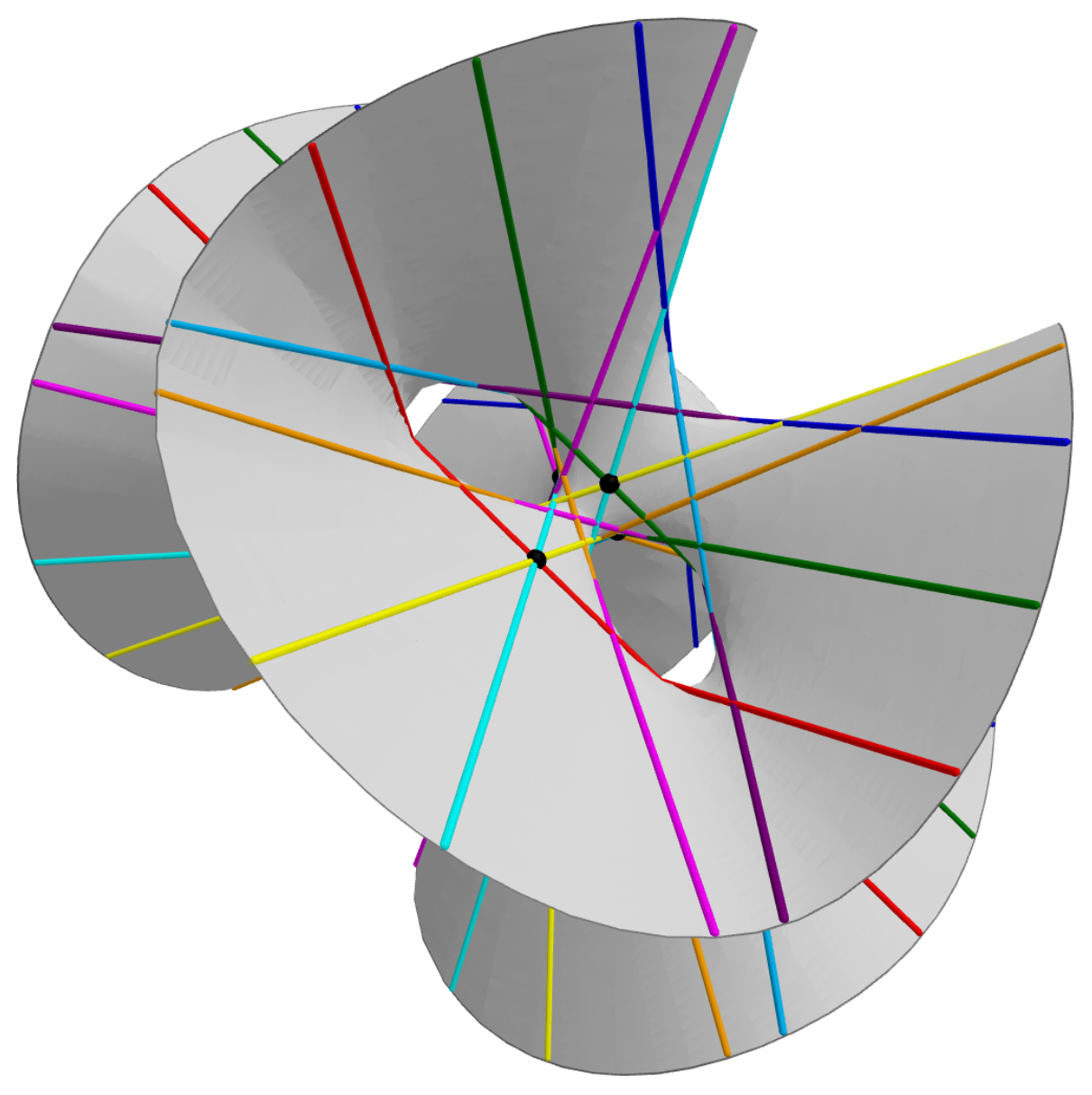

One of the most striking features of a smooth cubic surface is that it contains exactly 27 lines, a classical result first proved by Arthur Cayley and George Salmon in 1849, who showed that this is the maximum finite number of straight lines lying on such a surface.[2] These lines are exceptional curves with self-intersection number , and their configuration—where each line intersects exactly ten others—generates the Picard group of the surface, which has rank seven and is isomorphic to the lattice .[1] The lines can be classified into types based on their normal bundles, with those of the second type lying in a unique tangent plane.[1]

Cubic surfaces are rational varieties, meaning they are birational to the projective plane via the blow-up at six general points, which resolves the indeterminacies of the rational map given by the linear system of cubics through those points.[1] This birational equivalence highlights their role in enumerative geometry and moduli theory, where the four-dimensional moduli space of cubic surfaces exhibits rich period maps and monodromy actions related to the Weyl group .[1] Historically, the study of cubic surfaces advanced 19th-century algebraic geometry, with contributions from Ludwig Schläfli on singular cases and later developments linking them to derived categories and hyperkähler geometry in higher-dimensional analogs like cubic fourfolds.[2]

This classification highlights how singularities enhance symmetry, with finite groups arising in highly symmetric nodal configurations and infinite groups in those with elliptic or higher-codimension features.

Automorphism groups are computed by resolving the singularities via successive blow-ups, typically at six points corresponding to the exceptional configuration, and analyzing the induced action on the Picard lattice of the minimal resolution, which is a hyperbolic lattice of rank 7 minus the singularity contributions. Monodromy representations from the deformation space of the resolved surface map to the orthogonal group of the lattice, revealing the finite part of the automorphism group, while the connected component arises from the identity component of the automorphism group of the anticanonical model. This approach leverages the fact that automorphisms lift uniquely to the resolution for normal surfaces.

A prominent example is the Cayley cubic surface, defined by the equation in , which has four nodes at the points (and permutations), where is a primitive cube root of unity. Its automorphism group is isomorphic to of order 24, generated by permutations of the coordinate variables that preserve the symmetric form and transitively act on the nodes; lines on the surface serve as invariants under this action. Singular variants of the Fermat cubic, such as those with imposed nodes via parameter specialization, can yield groups like for mixed nodal-cuspidal types, though these often introduce parameters.[26]

Recent studies have explored Cremona transformations that preserve singularity types on cubic surfaces, extending the classical automorphism groups. For instance, birational maps induced by quadratic transformations centered at singular points can generate additional finite subgroups isomorphic to Weyl groups like in resolutions of nodal cubics with Picard lattice , acting as monodromy-invariant symmetries without altering the singularity locus. These transformations, analyzed post-2015, reveal hidden finite extensions in parameter-free families, such as order-51840 actions on certain three-nodal surfaces.[27]

Fundamentals

Definition and General Form

A cubic surface is defined as a hypersurface of degree 3 in the projective 3-space over an algebraically closed field, typically .[1] It is the zero locus of a homogeneous polynomial equation of degree 3 in the four homogeneous coordinates of .[1] The general form of such a surface is given by where is a cubic homogeneous polynomial in the variables .[1] A standard example is the Fermat cubic surface, normalized as which is smooth provided the characteristic of the base field is not 3.[1] For intuition in affine coordinates, one considers affine charts via dehomogenization; for instance, setting yields an affine cubic surface in defined by the corresponding inhomogeneous equation.[3] The parameter space of all cubic surfaces in is the projective space , corresponding to the 20 monomials of degree 3 in four variables, up to scalar multiple.[1] Accounting for the action of the projective linear group , which has dimension 15, the moduli space of smooth cubic surfaces is 4-dimensional.[4]Smoothness and Projective Embedding

A cubic surface in projective 3-space , defined by a homogeneous cubic polynomial , is smooth if it contains no singular points. A point is singular if and all partial derivatives for , where the variables are indexed accordingly.[5] This condition follows from the Jacobian criterion for hypersurfaces, which states that a hypersurface variety is smooth at a point if the rank of the Jacobian matrix (here, the row of partial derivatives) is equal to the codimension, ensuring the tangent space dimension matches the expected value.[6] For cubic surfaces, singularities occur only if the gradient vanishes simultaneously with at some point, and over algebraically closed fields, smooth cubics are non-singular by generic choice of coefficients.[1] Smooth cubic surfaces embed naturally as degree-3 subvarieties of via the complete linear system associated to the anticanonical bundle , where denotes the canonical divisor. By the adjunction formula for hypersurfaces, , with the hyperplane class pulled back from .[7] This embedding realizes the surface as a del Pezzo surface of degree 3, since the degree is , confirming that is very ample. Over the complex numbers, the Picard group has rank 7 and is generated by the hyperplane class together with the classes of the 27 lines on the surface, isomorphic to the lattice . Over number fields, the generic smooth cubic surface has Picard rank , with generated by .[1] A hyperplane section of a smooth cubic surface is a smooth plane cubic curve, whose genus is given by the formula for irreducible plane curves of degree : . For , this yields , so the section is an elliptic curve.[8] This elliptic nature highlights the surface's role in connecting cubic geometry to abelian varieties.Geometric Features

The 27 Lines

A fundamental feature of smooth cubic surfaces is the presence of exactly 27 lines. Over an algebraically closed field of characteristic not equal to 2 or 3, every smooth cubic surface in projective 3-space contains precisely 27 lines, a result originally established by Arthur Cayley and George Salmon in 1849.[2][9] To see this via intersection theory, note that any line on the surface is a smooth rational curve of degree 1 with respect to the hyperplane class . By the adjunction formula, for such a curve , we have , where is the genus and is the canonical class. Since on the cubic surface, this simplifies to , yielding . Thus, lines correspond to effective curves in the anticanonical class with self-intersection . The space of such curves is finite, and enumerative methods, such as Schubert calculus on the Grassmannian , show there are exactly 27 of them.[10][11] The 27 lines exhibit a rich combinatorial structure known as the Cayley-Salmon configuration, which realizes the root lattice of the exceptional Lie algebra . In this setup, the intersection form on the Picard group orthogonal to is isometric to the lattice, with the classes of the lines corresponding to a set of 27 vectors of norm . Each line intersects exactly 10 others transversely at distinct points, as determined by the inner products in the lattice: the total number of intersecting pairs is , while the remaining pairs are skew. This incidence graph encodes triples of mutually skew lines or concurrent lines in specific ways, reflecting the symmetry.[1][12] A special incidence occurs at Eckardt points, where three lines meet concurrently. These points are exceptional features, with most smooth cubic surfaces having none, though up to 18 are possible, as realized on the Fermat cubic surface . The presence of Eckardt points corresponds to a codimension-1 subset in the moduli space of cubic surfaces and influences the surface's automorphism group.[13][14]Blow-up Realization

A smooth cubic surface over an algebraically closed field is birationally equivalent to the blow-up of the projective plane at six points in general position, meaning no three points are collinear and the six points do not lie on a conic.[15] This construction yields a del Pezzo surface of degree 3, where the exceptional divisors arise from the blown-up points.[15] Let denote the blow-up morphism, with pullback of the hyperplane class on . The anticanonical divisor on is , which is very ample and embeds into via the complete linear system , realizing as a cubic surface in .[15] The self-intersection confirms the degree of the embedded surface, computed as follows: using , , , and for .[15] The exceptional divisors correspond to six of the 27 lines on the cubic surface. The remaining lines are the proper transforms of lines through pairs of points, given by classes for (15 lines), and the proper transforms of conics through five points, given by (6 lines).[15] Over an algebraically closed field, every smooth cubic surface is isomorphic to such a blow-up at six general points.[15] The birational map from to the cubic is given by the projection from the linear system , parametrizing the embedding.[15]Algebraic Properties

Rationality

A smooth cubic surface over an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero is unirational, as the projection from any line on the surface induces a dominant rational map to .[1] This follows from the existence of 27 lines on such a surface and the general fact that a smooth cubic hypersurface containing a line is unirational via projection.[16] Full rationality holds, as every smooth cubic surface is birational to . This birational equivalence arises as the inverse of the blow-up of at six points in general position—no three collinear and no six on a conic—established by Clebsch in 1871.[1] An explicit birational map can be constructed via stereographic projection from a point on the surface not lying on any of the 27 lines, parametrizing the surface rationally in terms of two parameters.[16] For the Clebsch diagonal cubic, defined as the intersection of the hypersurface in with the hyperplane , embedding it in , an explicit rational parametrization exists using quadratic forms in two variables, reflecting its symmetry under the action of .[17] This parametrization highlights the surface's rationality and its 27 real lines.[18] The rationality of smooth cubic surfaces over algebraically closed fields was classically established through the blow-up model by Clebsch and Noether in the late 19th century, with arithmetic aspects for non-closed fields developed by Coray and Tsfasman in 1983, building on Noether's methods for birational classification.[19][20]Automorphisms of Smooth Cubics

The automorphism group of a smooth cubic surface over an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero is finite and isomorphic to a finite subgroup of .[21] This group consists of projective linear transformations that preserve the defining equation of . For a general smooth cubic surface, is trivial, reflecting the discrete nature of the moduli space at generic points, which has dimension 4.[21] The group acts on the Picard group , preserving the hyperbolic intersection form of signature (1,6) on .[21] This action is faithful, embedding into the orthogonal group , which is generated by reflections across the classes of the 27 exceptional lines and isomorphic to the Weyl group of order 51840.[21] The isomorphism highlights the exceptional Lie structure underlying the geometry.[21] Thus, every automorphism induces a permutation of the 27 lines on , with the image lying in a conjugacy class of subgroups of . Computations of rely on classifying these induced actions on the Picard lattice, often via normal forms of the defining equation or counts of invariant lines and Eckardt points.[21] All possible finite groups arising this way over characteristic zero have been classified, with orders ranging from 1 up to 648.[21] Exceptional cases feature larger automorphism groups. The Fermat cubic surface, defined by , has of order 648, generated by scalar multiplications of order 3 on coordinates and permutations thereof.[21] The Clebsch cubic surface, defined by where are elementary symmetric polynomials in the coordinates, has of order 120, arising from its 10 Eckardt points and icosahedral symmetry.[21] These groups represent the maximal and notable exceptional symmetries, with loci of codimension 4 in the moduli space.[21]Singular Cases

Classification of Singularities

Singular cubic surfaces in over an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero possess isolated singularities that are rational double points, known as du Val singularities, which are classified by the ADE Dynkin diagrams up to type E. These singularities arise as hypersurface singularities defined by a cubic equation locally near the singular point, and their type is determined by the multiplicity and the structure of the tangent cone. The minimal resolution of such a singularity is achieved by blowing up the singular point successively, yielding an exceptional locus consisting of a chain or tree of -curves whose dual graph is the corresponding Dynkin diagram. The full classification of singular cubic surfaces by their singularities comprises 22 distinct types, encompassing combinations of multiple singularities of various ADE types, as established by Bruce and Wall. These types include single singularities like A, A, ..., A, D, D, E, and , as well as multiple ones such as 2A, 3A, 4A, AA, up to configurations like 3A. Ordinary singularities are those with a non-degenerate quadratic tangent cone, primarily nodes of type A (local equation higher terms ) and cusps of type A (local equation higher terms ), extending to higher A and D/E types where the blow-up process aligns with the hypersurface structure. A cubic surface admits at most four nodes, with equality realized uniquely by Cayley's nodal cubic surface. Non-ordinary singularities, such as A, D, and the parabolic , feature a degenerate tangent cone and lie on the Hessian discriminant surface, complicating their local analytic structure beyond simple quasi-homogeneity. Cusp singularities of higher order (A for ) and their resolutions involve extended blow-up sequences, where the exceptional curves form a linear chain of length , but non-ordinary cases may require additional normalization steps. The dimension of the parameter space for cubics with a prescribed singularity type varies; for example, the locus of cubics with four A singularities is 0-dimensional (a single orbit under PGL(4)), while those with a single E form a curve.[22] Modern computational algebraic geometry has refined this classification by linking singularity types to invariants like the rank of the apolar ideal and exploring degenerations. Seigal computed the possible ranks (from 3 to 6 for isolated singularities) for each of the 22 types, showing that non-ordinary singularities correspond to rank-6 forms whose zero loci close the Hessian discriminant. Additionally, toric degenerations of smooth cubic surfaces, obtained by degenerating their Cox rings to toric algebras via Khovanskii bases, yield singular toric fibers whose singularities are toric rational double points, classifiable combinatorially by the associated cones; computational enumeration identifies 78 moneric classes, with 38 being Khovanskii bases supporting quasi-smooth toric models where singularities occur only at torus-fixed points. These approaches, using tools like Macaulay2 and tropical geometry, extend the classical list to families of semi-stable reductions over discrete valuation rings.[22][23]Lines on Singular Cubics

Singular cubic surfaces, classified by their rational double point singularities of ADE type, exhibit a reduced number of lines compared to the 27 on smooth cubics, with the count varying by singularity configuration. For instance, a surface with a single nodal singularity of type contains exactly 21 lines, reflecting the coalescence of six lines from the smooth case into pairs intersecting at the node.[24] More generally, across ADE types, the numbers decrease as follows: 21 for , 15 for , and 1 for , as detailed in recent analyses of line configurations on resolved models.[24] Lines on these singular surfaces often persist through the singularities or become tangent to the singular locus, altering their intersections from the skew configurations typical in smooth cases. Computationally, such lines can be identified by restricting the defining cubic equation to parametrized lines and imposing identical vanishing, with special attention to those passing through singular points where partial derivatives vanish; these must lie within the projectivized tangent cone while satisfying higher-order conditions from the cubic terms. In singular settings, configurations change such that multiple lines may coincide at the singularity or embed within the exceptional strata of the minimal resolution, reducing the total distinct count and modifying incidence relations. A prominent example is the Cayley cubic surface, defined by the equation (up to projective equivalence), which possesses four nodal singularities and exactly 9 lines: six forming the edges of a tetrahedron through the nodes and three additional transversal lines.[25] Another illustrative case arises in projections related to higher-degree surfaces like the Barth sextic, where the cubic model inherits a singular structure with 9 lines concentrated near the projected singularities, emphasizing the persistence of linear features despite degeneracy. Recent work, including updates from Manin's perspectives on cubic geometry in the 2020s, confirms these counts for all ADE configurations, linking them to the root lattices underlying the singularities.Automorphism Groups of Singular Cubics

Singular cubic surfaces in projective 3-space often admit larger automorphism groups compared to their smooth counterparts, owing to the additional flexibility introduced by singularities, which can act as fixed points or orbits under group actions. The classification of these groups is particularly tractable for "parameter-free" cases, where the normal forms of the surfaces have no free parameters, leading to rigid geometries without moduli spaces. In these instances, the automorphism groups can be finite or infinite, depending on the singularity type, and are determined by the action on the resolved surface and its exceptional divisors. A comprehensive classification of automorphism groups for normal singular cubic surfaces with no parameters, based on their ADE or elliptic singularities, reveals a variety of structures. For surfaces with rational double points (ADE types), the groups range from small finite ones like for a single node () to larger finite groups such as the symmetric group for the four-nodal case (). Other examples include semi-direct products involving multiplicative groups for more complex configurations, such as for three singularities. These groups preserve the singularity configuration and act faithfully on the resolved minimal model. The following table summarizes key parameter-free cases and their automorphism groups:| Singularity Type | Automorphism Group | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single node; involution swapping exceptional curve. | ||

| Four nodes; permutes the nodes transitively. | ||

| Infinite; acts on three cusps. | ||

| Finite extension involving rotations. |