Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dual graph

View on Wikipedia

In the mathematical discipline of graph theory, the dual graph of a planar graph G is a graph that has a vertex for each face of G. The dual graph has an edge for each pair of faces in G that are separated from each other by an edge, and a self-loop when the same face appears on both sides of an edge. Thus, each edge e of G has a corresponding dual edge, whose endpoints are the dual vertices corresponding to the faces on either side of e. The definition of the dual depends on the choice of embedding of the graph G, so it is a property of plane graphs (graphs that are already embedded in the plane) rather than planar graphs (graphs that may be embedded but for which the embedding is not yet known). For planar graphs generally, there may be multiple dual graphs, depending on the choice of planar embedding of the graph.

Historically, the first form of graph duality to be recognized was the association of the Platonic solids into pairs of dual polyhedra. Graph duality is a topological generalization of the geometric concepts of dual polyhedra and dual tessellations, and is in turn generalized combinatorially by the concept of a dual matroid. Variations of planar graph duality include a version of duality for directed graphs, and duality for graphs embedded onto non-planar two-dimensional surfaces.

These notions of dual graphs should not be confused with a different notion, the edge-to-vertex dual or line graph of a graph.

The term dual is used because the property of being a dual graph is symmetric, meaning that if H is a dual of a connected graph G, then G is a dual of H. When discussing the dual of a graph G, the graph G itself may be referred to as the "primal graph". Many other graph properties and structures may be translated into other natural properties and structures of the dual. For instance, cycles are dual to cuts, spanning trees are dual to the complements of spanning trees, and simple graphs (without parallel edges or self-loops) are dual to 3-edge-connected graphs.

Graph duality can help explain the structure of mazes and of drainage basins. Dual graphs have also been applied in computer vision, computational geometry, mesh generation, and the design of integrated circuits.

Examples

[edit]Cycles and dipoles

[edit]The unique planar embedding of a cycle graph divides the plane into only two regions, the inside and outside of the cycle, by the Jordan curve theorem. However, in an n-cycle, these two regions are separated from each other by n different edges. Therefore, the dual graph of the n-cycle is a multigraph with two vertices (dual to the regions), connected to each other by n dual edges. Such a graph is called a multiple edge, linkage, or sometimes a dipole graph. Conversely, the dual to an n-edge dipole graph is an n-cycle.[1]

Dual polyhedra

[edit]

According to Steinitz's theorem, every polyhedral graph (the graph formed by the vertices and edges of a three-dimensional convex polyhedron) must be planar and 3-vertex-connected, and every 3-vertex-connected planar graph comes from a convex polyhedron in this way. Every three-dimensional convex polyhedron has a dual polyhedron; the dual polyhedron has a vertex for every face of the original polyhedron, with two dual vertices adjacent whenever the corresponding two faces share an edge. Whenever two polyhedra are dual, their graphs are also dual. For instance the Platonic solids come in dual pairs, with the octahedron dual to the cube, the dodecahedron dual to the icosahedron, and the tetrahedron dual to itself.[2] Polyhedron duality can also be extended to duality of higher dimensional polytopes,[3] but this extension of geometric duality does not have clear connections to graph-theoretic duality.

Self-dual graphs

[edit]

A plane graph is said to be self-dual if it is isomorphic to its dual graph. The wheel graphs provide an infinite family of self-dual graphs coming from self-dual polyhedra (the pyramids).[4][5] However, there also exist self-dual graphs that are not polyhedral, such as the one shown. Servatius & Christopher (1992) describe two operations, adhesion and explosion, that can be used to construct a self-dual graph containing a given planar graph; for instance, the self-dual graph shown can be constructed as the adhesion of a tetrahedron with its dual.[5]

It follows from Euler's formula that every self-dual graph with n vertices has exactly 2n − 2 edges.[6] Every simple self-dual planar graph contains at least four vertices of degree three, and every self-dual embedding has at least four triangular faces.[7]

Properties

[edit]Many natural and important concepts in graph theory correspond to other equally natural but different concepts in the dual graph. Because the dual of the dual of a connected plane graph is isomorphic to the primal graph,[8] each of these pairings is bidirectional: if concept X in a planar graph corresponds to concept Y in the dual graph, then concept Y in a planar graph corresponds to concept X in the dual.

Simple graphs versus multigraphs

[edit]The dual of a simple graph need not be simple: it may have self-loops (an edge with both endpoints at the same vertex) or multiple edges connecting the same two vertices, as was already evident in the example of dipole multigraphs being dual to cycle graphs. As a special case of the cut-cycle duality discussed below, the bridges of a planar graph G are in one-to-one correspondence with the self-loops of the dual graph.[9] For the same reason, a pair of parallel edges in a dual multigraph (that is, a length-2 cycle) corresponds to a 2-edge cutset in the primal graph (a pair of edges whose deletion disconnects the graph). Therefore, a planar graph is simple if and only if its dual has no 1- or 2-edge cutsets; that is, if it is 3-edge-connected. The simple planar graphs whose duals are simple are exactly the 3-edge-connected simple planar graphs.[10] This class of graphs includes, but is not the same as, the class of 3-vertex-connected simple planar graphs. For instance, the figure showing a self-dual graph is 3-edge-connected (and therefore its dual is simple) but is not 3-vertex-connected.

Uniqueness

[edit]

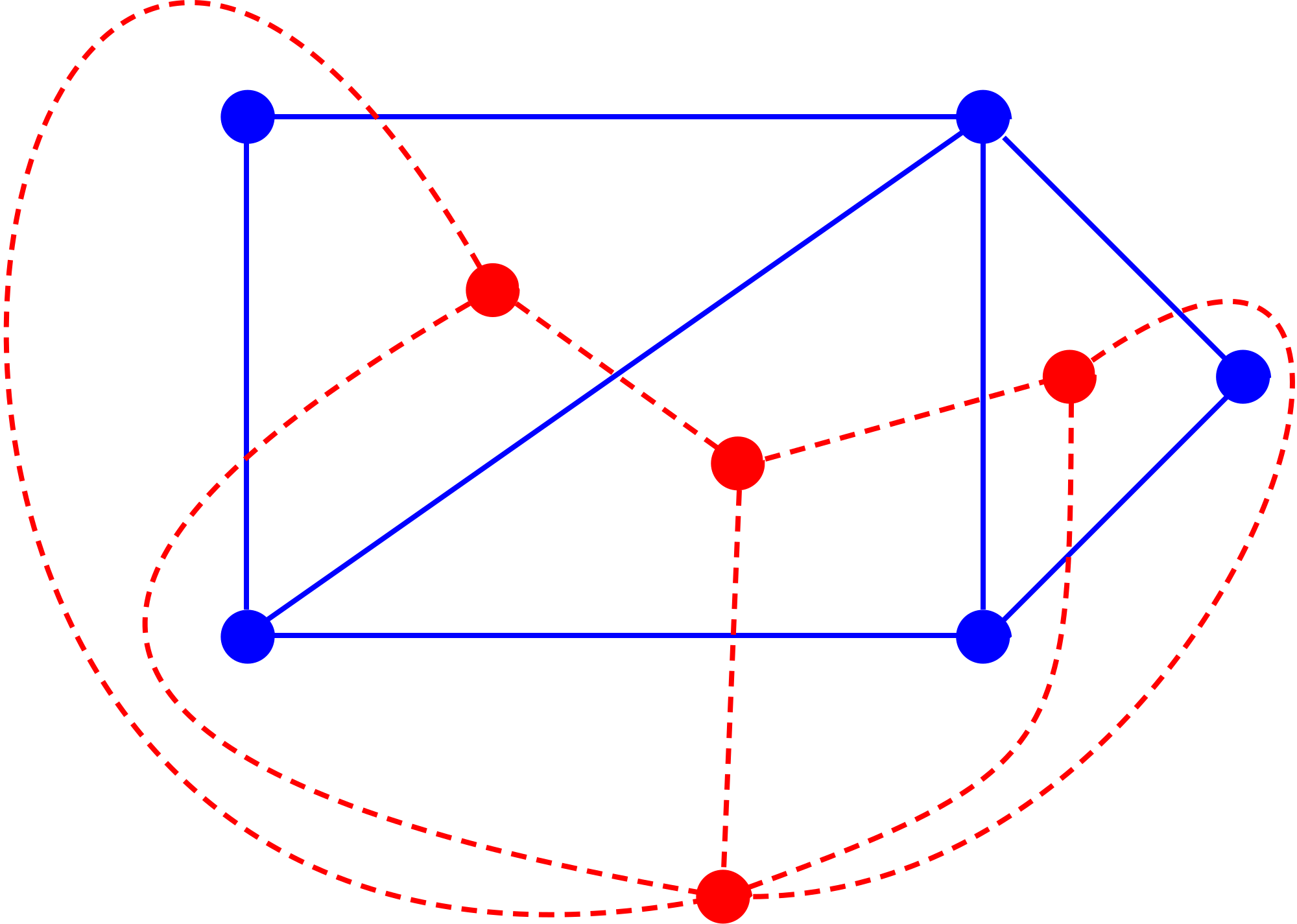

Because the dual graph depends on a particular embedding, the dual graph of a planar graph is not unique, in the sense that the same planar graph can have non-isomorphic dual graphs.[11] In the picture, the blue graphs are isomorphic but their dual red graphs are not. The upper red dual has a vertex with degree 6 (corresponding to the outer face of the blue graph) while in the lower red graph all degrees are less than 6.

Hassler Whitney showed that if the graph is 3-connected then the embedding, and thus the dual graph, is unique.[12] By Steinitz's theorem, these graphs are exactly the polyhedral graphs, the graphs of convex polyhedra. A planar graph is 3-vertex-connected if and only if its dual graph is 3-vertex-connected. Moreover, a planar biconnected graph has a unique embedding, and therefore also a unique dual, if and only if it is a subdivision of a 3-vertex-connected planar graph (a graph formed from a 3-vertex-connected planar graph by replacing some of its edges by paths).[13] For some planar graphs that are not 3-vertex-connected, such as the complete bipartite graph K2,4, the embedding is not unique, but all embeddings are isomorphic. When this happens, correspondingly, all dual graphs are isomorphic.

Because different embeddings may lead to different dual graphs, testing whether one graph is a dual of another (without already knowing their embeddings) is a nontrivial algorithmic problem. For biconnected graphs, it can be solved in polynomial time by using the SPQR trees of the graphs to construct a canonical form for the equivalence relation of having a shared mutual dual. For instance, the two red graphs in the illustration are equivalent according to this relation. However, for planar graphs that are not biconnected, this relation is not an equivalence relation and the problem of testing mutual duality is NP-complete.[14]

Cuts and cycles

[edit]A cutset in an arbitrary connected graph is a subset of edges defined from a partition of the vertices into two subsets, by including an edge in the subset when it has one endpoint on each side of the partition. Removing the edges of a cutset necessarily splits the graph into at least two connected components. A minimal cutset (also called a bond) is a cutset with the property that every proper subset of the cutset is not itself a cut. A minimal cutset of a connected graph necessarily separates its graph into exactly two components, and consists of the set of edges that have one endpoint in each component.[15] A simple cycle is a connected subgraph in which each vertex of the cycle is incident to exactly two edges of the cycle.[16]

In a connected planar graph G, every simple cycle of G corresponds to a minimal cutset in the dual of G, and vice versa.[17] This can be seen as a form of the Jordan curve theorem: each simple cycle separates the faces of G into the faces in the interior of the cycle and the faces of the exterior of the cycle, and the duals of the cycle edges are exactly the edges that cross from the interior to the exterior.[18] The girth of any planar graph (the size of its smallest cycle) equals the edge connectivity of its dual graph (the size of its smallest cutset).[19]

This duality extends from individual cutsets and cycles to vector spaces defined from them. The cycle space of a graph is defined as the family of all subgraphs that have even degree at each vertex; it can be viewed as a vector space over the two-element finite field, with the symmetric difference of two sets of edges acting as the vector addition operation in the vector space. Similarly, the cut space of a graph is defined as the family of all cutsets, with vector addition defined in the same way. Then the cycle space of any planar graph and the cut space of its dual graph are isomorphic as vector spaces.[20] Thus, the rank of a planar graph (the dimension of its cut space) equals the cyclotomic number of its dual (the dimension of its cycle space) and vice versa.[11] A cycle basis of a graph is a set of simple cycles that form a basis of the cycle space (every even-degree subgraph can be formed in exactly one way as a symmetric difference of some of these cycles). For edge-weighted planar graphs (with sufficiently general weights that no two cycles have the same weight) the minimum-weight cycle basis of the graph is dual to the Gomory–Hu tree of the dual graph, a collection of nested cuts that together include a minimum cut separating each pair of vertices in the graph. Each cycle in the minimum weight cycle basis has a set of edges that are dual to the edges of one of the cuts in the Gomory–Hu tree. When cycle weights may be tied, the minimum-weight cycle basis may not be unique, but in this case it is still true that the Gomory–Hu tree of the dual graph corresponds to one of the minimum weight cycle bases of the graph.[20]

In directed planar graphs, simple directed cycles are dual to directed cuts (partitions of the vertices into two subsets such that all edges go in one direction, from one subset to the other). Strongly oriented planar graphs (graphs whose underlying undirected graph is connected, and in which every edge belongs to a cycle) are dual to directed acyclic graphs in which no edge belongs to a cycle. To put this another way, the strong orientations of a connected planar graph (assignments of directions to the edges of the graph that result in a strongly connected graph) are dual to acyclic orientations (assignments of directions that produce a directed acyclic graph).[21] In the same way, dijoins (sets of edges that include an edge from each directed cut) are dual to feedback arc sets (sets of edges that include an edge from each cycle).[22]

Spanning trees

[edit]

A spanning tree may be defined as a set of edges that, together with all of the vertices of the graph, forms a connected and acyclic subgraph. But, by cut-cycle duality, if a set S of edges in a planar graph G is acyclic (has no cycles), then the set of edges dual to S has no cuts, from which it follows that the complementary set of dual edges (the duals of the edges that are not in S) forms a connected subgraph. Symmetrically, if S is connected, then the edges dual to the complement of S form an acyclic subgraph. Therefore, when S has both properties – it is connected and acyclic – the same is true for the complementary set in the dual graph. That is, each spanning tree of G is complementary to a spanning tree of the dual graph, and vice versa. Thus, the edges of any planar graph and its dual can together be partitioned (in multiple different ways) into two spanning trees, one in the primal and one in the dual, that together extend to all the vertices and faces of the graph but never cross each other. In particular, the minimum spanning tree of G is complementary to the maximum spanning tree of the dual graph.[23] However, this does not work for shortest path trees, even approximately: there exist planar graphs such that, for every pair of a spanning tree in the graph and a complementary spanning tree in the dual graph, at least one of the two trees has distances that are significantly longer than the distances in its graph.[24]

An example of this type of decomposition into interdigitating trees can be seen in some simple types of mazes, with a single entrance and no disconnected components of its walls. In this case both the maze walls and the space between the walls take the form of a mathematical tree. If the free space of the maze is partitioned into simple cells (such as the squares of a grid) then this system of cells can be viewed as an embedding of a planar graph, in which the tree structure of the walls forms a spanning tree of the graph and the tree structure of the free space forms a spanning tree of the dual graph.[25] Similar pairs of interdigitating trees can also be seen in the tree-shaped pattern of streams and rivers within a drainage basin and the dual tree-shaped pattern of ridgelines separating the streams.[26]

This partition of the edges and their duals into two trees leads to a simple proof of Euler’s formula V − E + F = 2 for planar graphs with V vertices, E edges, and F faces. Any spanning tree and its complementary dual spanning tree partition the edges into two subsets of V − 1 and F − 1 edges respectively, and adding the sizes of the two subsets gives the equation

- E = (V − 1) + (F − 1)

which may be rearranged to form Euler's formula. According to Duncan Sommerville, this proof of Euler's formula is due to K. G. C. Von Staudt’s Geometrie der Lage (Nürnberg, 1847).[27]

In nonplanar surface embeddings the set of dual edges complementary to a spanning tree is not a dual spanning tree. Instead this set of edges is the union of a dual spanning tree with a small set of extra edges whose number is determined by the genus of the surface on which the graph is embedded. The extra edges, in combination with paths in the spanning trees, can be used to generate the fundamental group of the surface.[28]

Additional properties

[edit]Any counting formula involving vertices and faces that is valid for all planar graphs may be transformed by planar duality into an equivalent formula in which the roles of the vertices and faces have been swapped. Euler's formula, which is self-dual, is one example. Another given by Harary involves the handshaking lemma, according to which the sum of the degrees of the vertices of any graph equals twice the number of edges. In its dual form, this lemma states that in a plane graph, the sum of the numbers of sides of the faces of the graph equals twice the number of edges.[29]

The medial graph of a plane graph is isomorphic to the medial graph of its dual. Two planar graphs can have isomorphic medial graphs only if they are dual to each other.[30]

A planar graph with four or more vertices is maximal (no more edges can be added while preserving planarity) if and only if its dual graph is both 3-vertex-connected and 3-regular.[31]

A connected planar graph is Eulerian (has even degree at every vertex) if and only if its dual graph is bipartite.[32] A Hamiltonian cycle in a planar graph G corresponds to a partition of the vertices of the dual graph into two subsets (the interior and exterior of the cycle) whose induced subgraphs are both trees. In particular, Barnette's conjecture on the Hamiltonicity of cubic bipartite polyhedral graphs is equivalent to the conjecture that every Eulerian maximal planar graph can be partitioned into two induced trees.[33]

If a planar graph G has Tutte polynomial TG(x,y), then the Tutte polynomial of its dual graph is obtained by swapping x and y. For this reason, if some particular value of the Tutte polynomial provides information about certain types of structures in G, then swapping the arguments to the Tutte polynomial will give the corresponding information for the dual structures. For instance, the number of strong orientations is TG(0,2) and the number of acyclic orientations is TG(2,0).[34] For bridgeless planar graphs, graph colorings with k colors correspond to nowhere-zero flows modulo k on the dual graph. For instance, the four color theorem (the existence of a 4-coloring for every planar graph) can be expressed equivalently as stating that the dual of every bridgeless planar graph has a nowhere-zero 4-flow. The number of k-colorings is counted (up to an easily computed factor) by the Tutte polynomial value TG(1 − k,0) and dually the number of nowhere-zero k-flows is counted by TG(0,1 − k).[35]

An st-planar graph is a connected planar graph together with a bipolar orientation of that graph, an orientation that makes it acyclic with a single source and a single sink, both of which are required to be on the same face as each other. Such a graph may be made into a strongly connected graph by adding one more edge, from the sink back to the source, through the outer face. The dual of this augmented planar graph is itself the augmentation of another st-planar graph.[36]

Variations

[edit]Directed graphs

[edit]In a directed plane graph, the dual graph may be made directed as well, by orienting each dual edge by a 90° clockwise turn from the corresponding primal edge.[36] Strictly speaking, this construction is not a duality of directed planar graphs, because starting from a graph G and taking the dual twice does not return to G itself, but instead constructs a graph isomorphic to the transpose graph of G, the graph formed from G by reversing all of its edges. Taking the dual four times returns to the original graph.

Weak dual

[edit]The weak dual of a plane graph is the subgraph of the dual graph whose vertices correspond to the bounded faces of the primal graph. A plane graph is outerplanar if and only if its weak dual is a forest. For any plane graph G, let G+ be the plane multigraph formed by adding a single new vertex v in the unbounded face of G, and connecting v to each vertex of the outer face (multiple times, if a vertex appears multiple times on the boundary of the outer face); then, G is the weak dual of the (plane) dual of G+.[37]

Infinite graphs and tessellations

[edit]The concept of duality applies as well to infinite graphs embedded in the plane as it does to finite graphs. However, care is needed to avoid topological complications such as points of the plane that are neither part of an open region disjoint from the graph nor part of an edge or vertex of the graph. When all faces are bounded regions surrounded by a cycle of the graph, an infinite planar graph embedding can also be viewed as a tessellation of the plane, a covering of the plane by closed disks (the tiles of the tessellation) whose interiors (the faces of the embedding) are disjoint open disks. Planar duality gives rise to the notion of a dual tessellation, a tessellation formed by placing a vertex at the center of each tile and connecting the centers of adjacent tiles.[38]

The concept of a dual tessellation can also be applied to partitions of the plane into finitely many regions. It is closely related to but not quite the same as planar graph duality in this case. For instance, the Voronoi diagram of a finite set of point sites is a partition of the plane into polygons within which one site is closer than any other. The sites on the convex hull of the input give rise to unbounded Voronoi polygons, two of whose sides are infinite rays rather than finite line segments. The dual of this diagram is the Delaunay triangulation of the input, a planar graph that connects two sites by an edge whenever there exists a circle that contains those two sites and no other sites. The edges of the convex hull of the input are also edges of the Delaunay triangulation, but they correspond to rays rather than line segments of the Voronoi diagram. This duality between Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay triangulations can be turned into a duality between finite graphs in either of two ways: by adding an artificial vertex at infinity to the Voronoi diagram, to serve as the other endpoint for all of its rays,[39] or by treating the bounded part of the Voronoi diagram as the weak dual of the Delaunay triangulation. Although the Voronoi diagram and Delaunay triangulation are dual, their embedding in the plane may have additional crossings beyond the crossings of dual pairs of edges. Each vertex of the Delaunay triangle is positioned within its corresponding face of the Voronoi diagram. Each vertex of the Voronoi diagram is positioned at the circumcenter of the corresponding triangle of the Delaunay triangulation, but this point may lie outside its triangle.

Nonplanar embeddings

[edit]The concept of duality can be extended to graph embeddings on two-dimensional manifolds other than the plane. The definition is the same: there is a dual vertex for each connected component of the complement of the graph in the manifold, and a dual edge for each graph edge connecting the two dual vertices on either side of the edge. In most applications of this concept, it is restricted to embeddings with the property that each face is a topological disk; this constraint generalizes the requirement for planar graphs that the graph be connected. With this constraint, the dual of any surface-embedded graph has a natural embedding on the same surface, such that the dual of the dual is isomorphic to and isomorphically embedded to the original graph. For instance, the complete graph K7 is a toroidal graph: it is not planar but can be embedded in a torus, with each face of the embedding being a triangle. This embedding has the Heawood graph as its dual graph.[40]

The same concept works equally well for non-orientable surfaces. For instance, K6 can be embedded in the projective plane with ten triangular faces as the hemi-icosahedron, whose dual is the Petersen graph embedded as the hemi-dodecahedron.[41]

Even planar graphs may have nonplanar embeddings, with duals derived from those embeddings that differ from their planar duals. For instance, the four Petrie polygons of a cube (hexagons formed by removing two opposite vertices of the cube) form the hexagonal faces of an embedding of the cube in a torus. The dual graph of this embedding has four vertices forming a complete graph K4 with doubled edges. In the torus embedding of this dual graph, the six edges incident to each vertex, in cyclic order around that vertex, cycle twice through the three other vertices. In contrast to the situation in the plane, this embedding of the cube and its dual is not unique; the cube graph has several other torus embeddings, with different duals.[40]

Many of the equivalences between primal and dual graph properties of planar graphs fail to generalize to nonplanar duals, or require additional care in their generalization.

Another operation on surface-embedded graphs is the Petrie dual, which uses the Petrie polygons of the embedding as the faces of a new embedding. Unlike the usual dual graph, it has the same vertices as the original graph, but generally lies on a different surface.[42] Surface duality and Petrie duality are two of the six Wilson operations, and together generate the group of these operations.[43]

Matroids and algebraic duals

[edit]An algebraic dual of a connected graph G is a graph G* such that G and G* have the same set of edges, any cycle of G is a cut of G*, and any cut of G is a cycle of G*. Every planar graph has an algebraic dual, which is in general not unique (any dual defined by a plane embedding will do). The converse is actually true, as settled by Hassler Whitney in Whitney's planarity criterion:[44]

- A connected graph G is planar if and only if it has an algebraic dual.

The same fact can be expressed in the theory of matroids. If M is the graphic matroid of a graph G, then a graph G* is an algebraic dual of G if and only if the graphic matroid of G* is the dual matroid of M. Then Whitney's planarity criterion can be rephrased as stating that the dual matroid of a graphic matroid M is itself a graphic matroid if and only if the underlying graph G of M is planar. If G is planar, the dual matroid is the graphic matroid of the dual graph of G. In particular, all dual graphs, for all the different planar embeddings of G, have isomorphic graphic matroids.[45]

For nonplanar surface embeddings, unlike planar duals, the dual graph is not generally an algebraic dual of the primal graph. And for a non-planar graph G, the dual matroid of the graphic matroid of G is not itself a graphic matroid. However, it is still a matroid whose circuits correspond to the cuts in G, and in this sense can be thought of as a combinatorially generalized algebraic dual of G.[46]

The duality between Eulerian and bipartite planar graphs can be extended to binary matroids (which include the graphic matroids derived from planar graphs): a binary matroid is Eulerian if and only if its dual matroid is bipartite.[32]

The two dual concepts of girth and edge connectivity are unified in matroid theory by matroid girth: the girth of the graphic matroid of a planar graph is the same as the graph's girth, and the girth of the dual matroid (the graphic matroid of the dual graph) is the edge connectivity of the graph.[19]

Applications

[edit]Along with its use in graph theory, the duality of planar graphs has applications in several other areas of mathematical and computational study.

In geographic information systems, flow networks (such as the networks showing how water flows in a system of streams and rivers) are dual to cellular networks describing drainage divides. This duality can be explained by modeling the flow network as a spanning tree on a grid graph of an appropriate scale, and modeling the drainage divide as the complementary spanning tree of ridgelines on the dual grid graph.[47]

In computer vision, digital images are partitioned into small square pixels, each of which has its own color. The dual graph of this subdivision into squares has a vertex per pixel and an edge between pairs of pixels that share an edge; it is useful for applications including clustering of pixels into connected regions of similar colors.[48]

In computational geometry, the duality between Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay triangulations implies that any algorithm for constructing a Voronoi diagram can be immediately converted into an algorithm for the Delaunay triangulation, and vice versa.[49] The same duality can also be used in finite element mesh generation. Lloyd's algorithm, a method based on Voronoi diagrams for moving a set of points on a surface to more evenly spaced positions, is commonly used as a way to smooth a finite element mesh described by the dual Delaunay triangulation. This method improves the mesh by making its triangles more uniformly sized and shaped.[50]

In the synthesis of CMOS circuits, the function to be synthesized is represented as a formula in Boolean algebra. Then this formula is translated into two series–parallel multigraphs. These graphs can be interpreted as circuit diagrams in which the edges of the graphs represent transistors, gated by the inputs to the function. One circuit computes the function itself, and the other computes its complement. One of the two circuits is derived by converting the conjunctions and disjunctions of the formula into series and parallel compositions of graphs, respectively. The other circuit reverses this construction, converting the conjunctions and disjunctions of the formula into parallel and series compositions of graphs.[51] These two circuits, augmented by an additional edge connecting the input of each circuit to its output, are planar dual graphs.[52]

History

[edit]The duality of convex polyhedra was recognized by Johannes Kepler in his 1619 book Harmonices Mundi.[53] Recognizable planar dual graphs, outside the context of polyhedra, appeared as early as 1725, in Pierre Varignon's posthumously published work, Nouvelle Méchanique ou Statique. This was even before Leonhard Euler's 1736 work on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg that is often taken to be the first work on graph theory. Varignon analyzed the forces on static systems of struts by drawing a graph dual to the struts, with edge lengths proportional to the forces on the struts; this dual graph is a type of Cremona diagram.[54] In connection with the four color theorem, the dual graphs of maps (subdivisions of the plane into regions) were mentioned by Alfred Kempe in 1879, and extended to maps on non-planar surfaces by Lothar Heffter in 1891.[55] Duality as an operation on abstract planar graphs was introduced by Hassler Whitney in 1931.[56]

Notes

[edit]- ^ van Lint, J. H.; Wilson, Richard Michael (1992), A Course in Combinatorics, Cambridge University Press, p. 411, ISBN 0-521-42260-4.

- ^ Bóna, Miklós (2006), A walk through combinatorics (2nd ed.), World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Hackensack, NJ, p. 276, doi:10.1142/6177, ISBN 981-256-885-9, MR 2361255.

- ^ Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), "2.3 Polarity", Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 152, pp. 59–64.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Self-dual graph", MathWorld

- ^ a b Servatius, Brigitte; Christopher, Peter R. (1992), "Construction of self-dual graphs", The American Mathematical Monthly, 99 (2): 153–158, doi:10.2307/2324184, JSTOR 2324184, MR 1144356.

- ^ Thulasiraman, K.; Swamy, M. N. S. (2011), Graphs: Theory and Algorithms, John Wiley & Sons, Exercise 7.11, p. 198, ISBN 978-1-118-03025-7.

- ^ See the proof of Theorem 5 in Servatius & Christopher (1992).

- ^ Nishizeki, Takao; Chiba, Norishige (2008), Planar Graphs: Theory and Algorithms, Dover Books on Mathematics, Dover Publications, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-486-46671-2.

- ^ Jensen, Tommy R.; Toft, Bjarne (1995), Graph Coloring Problems, Wiley-Interscience Series in Discrete Mathematics and Optimization, vol. 39, Wiley, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-471-02865-9,

note that "bridge" and "loop" are dual concepts

. - ^ Balakrishnan, V. K. (1997), Schaum's Outline of Graph Theory, McGraw Hill Professional, Problem 8.64, p. 229, ISBN 978-0-07-005489-9.

- ^ a b Foulds, L. R. (2012), Graph Theory Applications, Springer, pp. 66–67, ISBN 978-1-4612-0933-1.

- ^ Bondy, Adrian; Murty, U.S.R. (2008), "Planar Graphs", Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 244, Springer, Theorem 10.28, p. 267, doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-970-5, ISBN 978-1-84628-969-9, LCCN 2007923502

- ^ Nishizeki, Takao; Chiba, Norishige (2008), Planar Graphs: Theory and Algorithms, Dover Books on Mathematics, Dover Publications, Theorem 1.1, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-486-46671-2

- ^ Angelini, Patrizio; Bläsius, Thomas; Rutter, Ignaz (2014), "Testing mutual duality of planar graphs", International Journal of Computational Geometry and Applications, 24 (4): 325–346, arXiv:1303.1640, doi:10.1142/S0218195914600103, MR 3349917.

- ^ Diestel, Reinhard (2006), Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 173, Springer, p. 25, ISBN 978-3-540-26183-4.

- ^ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001) [1990], Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.), MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, p. 1081, ISBN 0-262-03293-7

- ^ Godsil, Chris; Royle, Gordon F. (2013), Algebraic Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 207, Springer, Theorem 14.3.1, p. 312, ISBN 978-1-4613-0163-9.

- ^ Oxley, J. G. (2006), Matroid Theory, Oxford Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 3, Oxford University Press, p. 93, ISBN 978-0-19-920250-8.

- ^ a b Cho, Jung Jin; Chen, Yong; Ding, Yu (2007), "On the (co)girth of a connected matroid", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 155 (18): 2456–2470, doi:10.1016/j.dam.2007.06.015, MR 2365057.

- ^ a b Hartvigsen, D.; Mardon, R. (1994), "The all-pairs min cut problem and the minimum cycle basis problem on planar graphs", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics, 7 (3): 403–418, doi:10.1137/S0895480190177042.

- ^ Noy, Marc (2001), "Acyclic and totally cyclic orientations in planar graphs", American Mathematical Monthly, 108 (1): 66–68, doi:10.2307/2695680, JSTOR 2695680, MR 1857074.

- ^ Gabow, Harold N. (1995), "Centroids, representations, and submodular flows", Journal of Algorithms, 18 (3): 586–628, doi:10.1006/jagm.1995.1022, MR 1334365

- ^ Tutte, W. T. (1984), Graph theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 21, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Advanced Book Program, p. 289, ISBN 0-201-13520-5, MR 0746795.

- ^ Riley, T. R.; Thurston, W. P. (2006), "The absence of efficient dual pairs of spanning trees in planar graphs", Electronic Journal of Combinatorics, 13 (1): Note 13, 7, doi:10.37236/1151, MR 2255413.

- ^ Lyons, Russell (1998), "A bird's-eye view of uniform spanning trees and forests", Microsurveys in discrete probability (Princeton, NJ, 1997), DIMACS Ser. Discrete Math. Theoret. Comput. Sci., vol. 41, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, pp. 135–162, MR 1630412. See in particular pp. 138–139.

- ^ Flammini, Alessandro (October 1996), Scaling Behavior for Models of River Network, Ph.D. thesis, International School for Advanced Studies, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Sommerville, D. M. Y. (1958), An Introduction to the Geometry of N Dimensions, Dover.

- ^ Eppstein, David (2003), "Dynamic generators of topologically embedded graphs", Proceedings of the 14th ACM/SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, pp. 599–608, arXiv:cs.DS/0207082.

- ^ Harary, Frank (1969), Graph Theory, Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Theorem 9.4, p. 142, MR 0256911.

- ^ Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay, eds. (2003), Handbook of Graph Theory, CRC Press, p. 724, ISBN 978-1-58488-090-5.

- ^ He, Xin (1999), "On floor-plan of plane graphs", SIAM Journal on Computing, 28 (6): 2150–2167, doi:10.1137/s0097539796308874.

- ^ a b Welsh, D. J. A. (1969), "Euler and bipartite matroids", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, 6 (4): 375–377, doi:10.1016/s0021-9800(69)80033-5, MR 0237368.

- ^ Florek, Jan (2010), "On Barnette's conjecture", Discrete Mathematics, 310 (10–11): 1531–1535, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2010.01.018, MR 2601261.

- ^ Las Vergnas, Michel (1980), "Convexity in oriented matroids", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 29 (2): 231–243, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(80)90082-9, MR 0586435.

- ^ Tutte, William Thomas (1953), A contribution to the theory of chromatic polynomials

- ^ a b di Battista, Giuseppe; Eades, Peter; Tamassia, Roberto; Tollis, Ioannis G. (1999), Graph Drawing: Algorithms for the Visualization of Graphs, Prentice Hall, p. 91, ISBN 978-0-13-301615-4.

- ^ Fleischner, Herbert J.; Geller, D. P.; Harary, Frank (1974), "Outerplanar graphs and weak duals", Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 38: 215–219, MR 0389672.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Dual Tessellation", MathWorld

- ^ Samet, Hanan (2006), Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures, Morgan Kaufmann, p. 348, ISBN 978-0-12-369446-1.

- ^ a b Gagarin, Andrei; Kocay, William; Neilson, Daniel (2003), "Embeddings of small graphs on the torus" (PDF), Cubo, 5: 351–371, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-01, retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ^ Nakamoto, Atsuhiro; Negami, Seiya (2000), "Full-symmetric embeddings of graphs on closed surfaces", Memoirs of Osaka Kyoiku University, 49 (1): 1–15, MR 1833214.

- ^ Pisanski, Tomaž; Randić, Milan (2000), "Bridges between geometry and graph theory" (PDF), in Gorini, Catherine A. (ed.), Geometry at Work, MAA Notes, vol. 53, Cambridge University Press, pp. 174–194, ISBN 9780883851647, MR 1782654

- ^ Jones, G. A.; Thornton, J. S. (1983), "Operations on maps, and outer automorphisms", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 35 (2): 93–103, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(83)90065-5, MR 0733017

- ^ Whitney, Hassler (1932), "Non-separable and planar graphs", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 34 (2): 339–362, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1932-1501641-2, PMC 1076008.

- ^ Oxley, J. G. (2006), "5.2 Duality in graphic matroids", Matroid Theory, Oxford graduate texts in mathematics, vol. 3, Oxford University Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-19-920250-8.

- ^ Tutte, W. T. (2012), Graph Theory As I Have Known It, Oxford Lecture Series in Mathematics and Its Applications, vol. 11, Oxford University Press, p. 87, ISBN 978-0-19-966055-1.

- ^ Chorley, Richard J.; Haggett, Peter (2013), Integrated Models in Geography, Routledge, p. 646, ISBN 978-1-135-12184-6.

- ^ Kandel, Abraham; Bunke, Horst; Last, Mark (2007), Applied Graph Theory in Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol. 52, Springer, p. 16, ISBN 978-3-540-68020-8.

- ^ Devadoss, Satyan L.; O'Rourke, Joseph (2011), Discrete and Computational Geometry, Princeton University Press, p. 111, ISBN 978-1-4008-3898-1.

- ^ Du, Qiang; Gunzburger, Max (2002), "Grid generation and optimization based on centroidal Voronoi tessellations", Applied Mathematics and Computation, 133 (2–3): 591–607, doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(01)00260-0.

- ^ Piguet, Christian (2004), "7.2.1 Static CMOS Logic", Low-Power Electronics Design, CRC Press, pp. 7-1 – 7-2, ISBN 978-1-4200-3955-9.

- ^ Kaeslin, Hubert (2008), "8.1.4 Composite or complex gates", Digital Integrated Circuit Design: From VLSI Architectures to CMOS Fabrication, Cambridge University Press, p. 399, ISBN 978-0-521-88267-5.

- ^ Richeson, David S. (2012), Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology, Princeton University Press, pp. 58–61, ISBN 978-1-4008-3856-1.

- ^ Rippmann, Matthias (2016), Funicular Shell Design: Geometric Approaches to Form Finding and Fabrication of Discrete Funicular Structures, Habilitation thesis, Diss. ETH No. 23307, ETH Zurich, pp. 39–40, doi:10.3929/ethz-a-010656780, hdl:20.500.11850/116926. See also Erickson, Jeff (June 9, 2016), Reciprocal force diagrams from Nouvelle Méchanique ou Statique by Pierre de Varignon (1725),

Is this the oldest illustration of duality between planar graphs?

. - ^ Biggs, Norman; Lloyd, E. Keith; Wilson, Robin J. (1998), Graph Theory, 1736–1936, Oxford University Press, p. 118, ISBN 978-0-19-853916-2.

- ^ Whitney, Hassler (1931), "A theorem on graphs", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series, 32 (2): 378–390, doi:10.2307/1968197, JSTOR 1968197, MR 1503003.

External links

[edit]Dual graph

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In graph theory, the dual graph of a planar graph embedded in the plane is a graph whose vertices correspond one-to-one with the faces of , including the unbounded outer face.[1] An edge exists in between two vertices if and only if the corresponding faces in share a boundary edge in the embedding; each such shared edge in corresponds uniquely to an edge in , ensuring that the number of edges in equals the number of edges in .[3] This construction depends on the specific planar embedding of , as different embeddings may yield non-isomorphic dual graphs, though for 3-connected planar graphs, the dual is unique up to isomorphism.[1] The dual graph interchanges the roles of vertices and faces in the primal graph : the number of vertices in equals the number of faces in (denoted ), and the number of faces in equals the number of vertices in (denoted .[3] Loops and multiple edges in transform into edges in and vice versa, preserving the total edge count .[3] For polyhedral graphs—those realizable as the 1-skeletons of convex polyhedra—the dual corresponds to the graph of the polyhedron's faces, satisfying Euler's formula in both primal and dual forms.[1] The concept of the dual graph was formalized combinatorially by Whitney, who showed that for 3-connected planar graphs, the combinatorial dual (defined via incidence relations) coincides with the geometric dual (derived from a plane embedding), establishing a foundational duality in planar graph theory.[1] This duality extends to multigraphs and allows the dual of the dual to recover the original graph, up to the embedding.[1]Construction

The dual graph of a connected plane graph is a multigraph constructed as follows: the vertex set consists of one vertex for each face of the embedding of , including the unbounded outer face. For each edge of , which separates two faces and (possibly the same face if is a loop or bridge), add an edge in connecting and ; if , this results in a loop at . Geometrically, this can be realized by placing each vertex in the interior of face and drawing edge as a curve that crosses transversely once and does not intersect any other edges of except at endpoints. This construction ensures a natural bijection between the edges of and , preserving the incidence structure between faces and edges. The resulting may contain multiple edges between the same pair of vertices if the corresponding faces in share multiple edges, and loops arise from bridges or loops in . the dual of recovers , establishing a mutual duality. Combinatorially, the construction can also be defined using the rotation system of the embedding: vertices of correspond to faces, and the cyclic order around each primal vertex induces the dual's structure, ensuring the embedding of reflects the primal's facial boundaries.[6] This approach, formalized by Whitney, guarantees that a graph admits such a dual construction if and only if it is planar.Examples

Cycles and dipoles

In planar graph theory, the relationship between cycles in a primal graph and structures in its dual graph highlights a fundamental duality. A simple cycle in the primal embedding separates the plane into an interior region and an exterior region, each constituting a face. The dual graph places a vertex for each such face and includes an edge for every primal edge bounding both faces. Thus, for an -cycle embedded in the plane, all primal edges lie between the two faces, resulting in parallel edges connecting the two corresponding dual vertices. This configuration forms a dipole subgraph in the dual. A dipole graph , also known as a linkage or bond graph, is defined as a multigraph with exactly two vertices joined by parallel edges, where .[7] The plane dual of the cycle graph is precisely the dipole graph .[8] Conversely, the dual of —embedded such that its multiple edges bound a single interior face—is the cycle graph . This reciprocity arises because the two vertices of represent the interior and exterior faces, while the parallel edges correspond to the edges of the bounding cycle in the primal. In a more general planar embedding of a graph , a simple cycle that serves as the shared boundary between exactly two faces and induces a dipole subgraph in the dual between the vertices representing and . If the cycle has length , the induced dipole has parallel edges. This property underscores the correspondence between cycles (minimal circuits enclosing a region) in the primal and minimal cut-sets (bonds separating two faces) in the dual, where the multiplicity reflects the cycle's length. For instance, consider a planar graph containing a 4-cycle bounding two adjacent faces; its dual includes a between the respective face-vertices. Dipoles also appear in topological graph theory when studying embeddings on surfaces, such as in genus distributions, where serves as a building block for analyzing voltage graphs and covering spaces. However, in the strict planar case, they primarily illustrate the local duality around separating cycles, providing insight into face adjacencies without altering global connectivity.Polyhedral duals

In graph theory, the dual graph of a polyhedron is defined by creating a vertex for each face of the polyhedron and placing an edge between two vertices if the corresponding faces share a boundary edge in the polyhedron.[1] This construction applies specifically to polyhedral graphs, which are the 1-skeleton graphs of convex polyhedra and, by Steinitz's theorem, are precisely the simple 3-connected planar graphs.[9] The resulting dual graph inherits the combinatorial structure of the polyhedron's faces, transforming face incidences into vertex adjacencies. For polyhedral graphs, the dual is unique because 3-connected planar graphs admit a unique embedding on the sphere up to homeomorphism, ensuring a canonical choice of faces for duality.[1] This uniqueness stems from Whitney's theorem on the rigidity of embeddings for such graphs.[10] Moreover, the dual graph of a polyhedral graph is itself polyhedral, as the geometric dual polyhedron—obtained by interchanging vertices and face centers—yields another convex polyhedron whose 1-skeleton is the dual graph.[10] Both the primal and dual satisfy Euler's formula , where the dual has , , and .[1] The edge degrees in the dual graph correspond to the face sizes of the original polyhedron: a face with sides becomes a vertex of degree in the dual.[1] Conversely, the vertex degrees in the primal become the face sizes in the dual polyhedron. This reciprocity preserves planarity and 3-connectivity, ensuring the dual remains embeddable as a polyhedral graph.[9] Classic examples illustrate these dual pairs among the Platonic solids. The cube, with 8 triangular faces, 12 edges, and 6 square faces, has a dual graph that is the 1-skeleton of the octahedron, featuring 6 vertices (one per cube face), 12 edges, and 8 triangular faces.[11] Similarly, the dodecahedron (20 vertices, 30 edges, 12 pentagonal faces) is dual to the icosahedron (12 vertices, 30 edges, 20 triangular faces), where each pentagon center of the dodecahedron connects to form the icosahedron's vertices.[11] The tetrahedron is self-dual in this sense, as its four triangular faces yield another tetrahedral graph upon duality.[11]| Primal Polyhedron | Vertices (V) | Edges (E) | Faces (F) | Dual Polyhedron | Vertex Degrees in Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cube | 8 | 12 | 6 | Octahedron | All degree 4 |

| Dodecahedron | 20 | 30 | 12 | Icosahedron | All degree 5 |

| Tetrahedron | 4 | 6 | 4 | Tetrahedron | All degree 3 |