Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Data parallelism

View on Wikipedia

Data parallelism is parallelization across multiple processors in parallel computing environments. It focuses on distributing the data across different nodes, which operate on the data in parallel. It can be applied on regular data structures like arrays and matrices by working on each element in parallel. It contrasts to task parallelism as another form of parallelism.

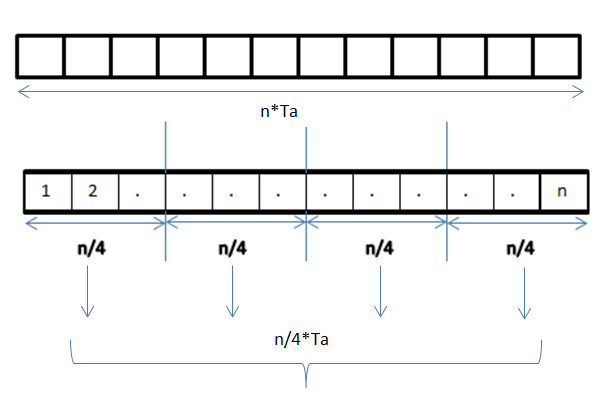

A data parallel job on an array of n elements can be divided equally among all the processors. Let us assume we want to sum all the elements of the given array and the time for a single addition operation is Ta time units. In the case of sequential execution, the time taken by the process will be n×Ta time units as it sums up all the elements of an array. On the other hand, if we execute this job as a data parallel job on 4 processors the time taken would reduce to (n/4)×Ta + merging overhead time units. Parallel execution results in a speedup of 4 over sequential execution. The locality of data references plays an important part in evaluating the performance of a data parallel programming model. Locality of data depends on the memory accesses performed by the program as well as the size of the cache.

History

[edit]Exploitation of the concept of data parallelism started in 1960s with the development of the Solomon machine.[1] The Solomon machine, also called a vector processor, was developed to expedite the performance of mathematical operations by working on a large data array (operating on multiple data in consecutive time steps). Concurrency of data operations was also exploited by operating on multiple data at the same time using a single instruction. These processors were called 'array processors'.[2] In the 1980s, the term was introduced [3] to describe this programming style, which was widely used to program Connection Machines in data parallel languages like C*. Today, data parallelism is best exemplified in graphics processing units (GPUs), which use both the techniques of operating on multiple data in space and time using a single instruction.

Most data parallel hardware supports only a fixed number of parallel levels, often only one. This means that within a parallel operation it is not possible to launch more parallel operations recursively, and means that programmers cannot make use of nested hardware parallelism. The programming language NESL was an early effort at implementing a nested data-parallel programming model on flat parallel machines, and in particular introduced the flattening transformation that transforms nested data parallelism to flat data parallelism. This work was continued by other languages such as Data Parallel Haskell and Futhark, although arbitrary nested data parallelism is not widely available in current data-parallel programming languages.

Description

[edit]In a multiprocessor system executing a single set of instructions (SIMD), data parallelism is achieved when each processor performs the same task on different distributed data. In some situations, a single execution thread controls operations on all the data. In others, different threads control the operation, but they execute the same code.

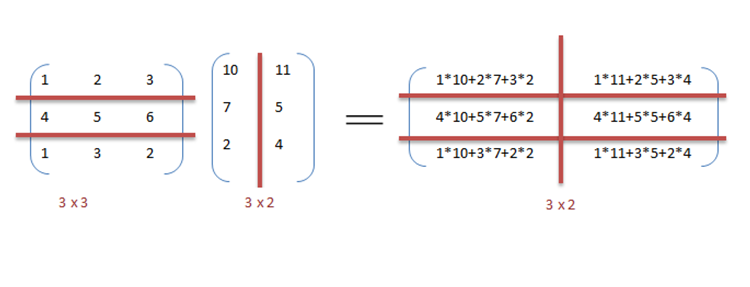

For instance, consider matrix multiplication and addition in a sequential manner as discussed in the example.

Example

[edit]Below is the sequential pseudo-code for multiplication and addition of two matrices where the result is stored in the matrix C. The pseudo-code for multiplication calculates the dot product of two matrices A, B and stores the result into the output matrix C.

If the following programs were executed sequentially, the time taken to calculate the result would be of the (assuming row lengths and column lengths of both matrices are n) and for multiplication and addition respectively.

// Matrix multiplication

for (int i = 0; i < A.rowLength(); i++) {

for (int k = 0; k < B.columnLength(); k++) {

int sum = 0;

for (int j = 0; j < A.columnLength(); j++) {

sum += A[i][j] * B[j][k];

}

C[i][k] = sum;

}

}

// Array addition

for (int i = 0; i < c.size(); i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

We can exploit data parallelism in the preceding code to execute it faster as the arithmetic is loop independent. Parallelization of the matrix multiplication code is achieved by using OpenMP. An OpenMP directive, "omp parallel for" instructs the compiler to execute the code in the for loop in parallel. For multiplication, we can divide matrix A and B into blocks along rows and columns respectively. This allows us to calculate every element in matrix C individually thereby making the task parallel. For example: A[m x n] dot B [n x k] can be finished in instead of when executed in parallel using m*k processors.

// Matrix multiplication in parallel

#pragma omp parallel for schedule(dynamic,1) collapse(2)

for (int i = 0; i < A.rowLength(); i++) {

for (int k = 0; k < B.columnLength(); k++) {

int sum = 0;

for (int j = 0; j < A.columnLength(); j++) {

sum += A[i][j] * B[j][k];

}

C[i][k] = sum;

}

}

It can be observed from the example that a lot of processors will be required as the matrix sizes keep on increasing. Keeping the execution time low is the priority but as the matrix size increases, we are faced with other constraints like complexity of such a system and its associated costs. Therefore, constraining the number of processors in the system, we can still apply the same principle and divide the data into bigger chunks to calculate the product of two matrices.[4]

For addition of arrays in a data parallel implementation, let's assume a more modest system with two central processing units (CPU) A and B, CPU A could add all elements from the top half of the arrays, while CPU B could add all elements from the bottom half of the arrays. Since the two processors work in parallel, the job of performing array addition would take one half the time of performing the same operation in serial using one CPU alone.

The program expressed in pseudocode below—which applies some arbitrary operation, foo, on every element in the array d—illustrates data parallelism:[nb 1]

if CPU = "a" then

lower_limit := 1

upper_limit := round(d.length / 2)

else if CPU = "b" then

lower_limit := round(d.length / 2) + 1

upper_limit := d.length

for i from lower_limit to upper_limit by 1 do

foo(d[i])

In an SPMD system executed on 2 processor system, both CPUs will execute the code.

Data parallelism emphasizes the distributed (parallel) nature of the data, as opposed to the processing (task parallelism). Most real programs fall somewhere on a continuum between task parallelism and data parallelism.

Steps to parallelization

[edit]The process of parallelizing a sequential program can be broken down into four discrete steps.[5]

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Decomposition | The program is broken down into tasks, the smallest exploitable unit of concurrence. |

| Assignment | Tasks are assigned to processes. |

| Orchestration | Data access, communication, and synchronization of processes. |

| Mapping | Processes are bound to processors. |

Data parallelism vs. task parallelism

[edit]| Data parallelism | Task parallelism |

|---|---|

| Same operations are performed on different subsets of same data. | Different operations are performed on the same or different data. |

| Synchronous computation | Asynchronous computation |

| Speedup is more as there is only one execution thread operating on all sets of data. | Speedup is less as each processor will execute a different thread or process on the same or different set of data. |

| Amount of parallelization is proportional to the input data size. | Amount of parallelization is proportional to the number of independent tasks to be performed. |

| Designed for optimum load balance on multi processor system. | Load balancing depends on the availability of the hardware and scheduling algorithms like static and dynamic scheduling. |

Data parallelism vs. model parallelism

[edit]| Data parallelism | Model parallelism |

|---|---|

| Same model is used for every thread but the data given to each of them is divided and shared. | Same data is used for every thread, and model is split among threads. |

| It is fast for small networks but very slow for large networks since large amounts of data needs to be transferred between processors all at once. | It is slow for small networks and fast for large networks. |

| Data parallelism is ideally used in array and matrix computations and convolutional neural networks | Model parallelism finds its applications in deep learning |

Mixed data and task parallelism

[edit]Data and task parallelism, can be simultaneously implemented by combining them together for the same application. This is called Mixed data and task parallelism. Mixed parallelism requires sophisticated scheduling algorithms and software support. It is the best kind of parallelism when communication is slow and number of processors is large.[7]

Mixed data and task parallelism has many applications. It is particularly used in the following applications:

- Mixed data and task parallelism finds applications in the global climate modeling. Large data parallel computations are performed by creating grids of data representing Earth's atmosphere and oceans and task parallelism is employed for simulating the function and model of the physical processes.

- In timing based circuit simulation. The data is divided among different sub-circuits and parallelism is achieved with orchestration from the tasks.

Data parallel programming environments

[edit]A variety of data parallel programming environments are available today, most widely used of which are:

- Message Passing Interface: It is a cross-platform message passing programming interface for parallel computers. It defines the semantics of library functions to allow users to write portable message passing programs in C, C++ and Fortran.

- OpenMP:[8] It's an Application Programming Interface (API) which supports shared memory programming models on multiple platforms of multiprocessor systems. Since version 4.5, OpenMP is also able to target devices other than typical CPUs. It can program FPGAs, DSPs, GPUs and more. It is not confined to GPUs like OpenACC.

- CUDA and OpenACC: CUDA and OpenACC (respectively) are parallel computing API platforms designed to allow a software engineer to utilize GPUs' computational units for general purpose processing.

- Threading Building Blocks and RaftLib: Both open source programming environments that enable mixed data/task parallelism in C/C++ environments across heterogeneous resources.

Applications

[edit]Data parallelism finds its applications in a variety of fields ranging from physics, chemistry, biology, material sciences to signal processing. Sciences imply data parallelism for simulating models like molecular dynamics,[9] sequence analysis of genome data [10] and other physical phenomenon. Driving forces in signal processing for data parallelism are video encoding, image and graphics processing, wireless communications [11] to name a few.

Data-intensive computing

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some input data (e.g. when

d.lengthevaluates to 1 androundrounds towards zero [this is just an example, there are no requirements on what type of rounding is used]) will lead tolower_limitbeing greater thanupper_limit, it's assumed that the loop will exit immediately (i.e. zero iterations will occur) when this happens.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Solomon Computer".

- ^ "SIMD/Vector/GPU" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Hillis, W. Daniel and Steele, Guy L., Data Parallel Algorithms Communications of the ACMDecember 1986

- ^ Barney, Blaise. "Introduction to Parallel Computing". computing.llnl.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-06-10. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Solihin, Yan (2016). Fundamentals of Parallel Architecture. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-1118-4.

- ^ "How to Parallelize Deep Learning on GPUs Part 2/2: Model Parallelism". Tim Dettmers. 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ^ "The Netlib" (PDF).

- ^ "OpenMP.org". openmp.org. Archived from the original on 2016-09-05. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Boyer, L. L; Pawley, G. S (1988-10-01). "Molecular dynamics of clusters of particles interacting with pairwise forces using a massively parallel computer". Journal of Computational Physics. 78 (2): 405–423. Bibcode:1988JCoPh..78..405B. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(88)90057-5.

- ^ Yap, T.K.; Frieder, O.; Martino, R.L. (1998). "Parallel computation in biological sequence analysis". IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems. 9 (3): 283–294. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.30.2819. doi:10.1109/71.674320.

- ^ Singh, H.; Lee, Ming-Hau; Lu, Guangming; Kurdahi, F.J.; Bagherzadeh, N.; Filho, E.M. Chaves (2000-06-01). "MorphoSys: an integrated reconfigurable system for data-parallel and computation-intensive applications". IEEE Transactions on Computers. 49 (5): 465–481. doi:10.1109/12.859540. ISSN 0018-9340.

- ^ Handbook of Cloud Computing, "Data-Intensive Technologies for Cloud Computing," by A.M. Middleton. Handbook of Cloud Computing. Springer, 2010.

- Hillis, W. Daniel and Steele, Guy L., Data Parallel Algorithms Communications of the ACM December 1986

- Blelloch, Guy E, Vector Models for Data-Parallel Computing MIT Press 1990. ISBN 0-262-02313-X

Data parallelism

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Data parallelism is a parallel computing paradigm in which the same operation is applied simultaneously to multiple subsets of a large dataset across multiple processors or nodes, emphasizing the division of data rather than tasks to enable concurrent execution of identical computations on different data portions. This approach treats the data structure, such as an array, as globally accessible, with each processor operating on a distinct partition. In parallel computing contexts, processors denote the hardware units—such as CPU cores or nodes in a cluster—that execute instructions independently. Threads represent lightweight sequences of instructions that share the same address space within a processor, facilitating fine-grained parallelism. In contrast, distributed memory architectures assign private memory to each processor, necessitating explicit communication mechanisms, like message passing, for data exchange between them.[6][7] Central principles of data parallelism revolve around data partitioning, synchronization, and load balancing. Data partitioning involves horizontally splitting the dataset into subsets, often using strategies like block distribution—where contiguous chunks are assigned to processors—or cyclic distribution—to promote even locality and minimize communication overhead. Synchronization occurs at key points to aggregate results, typically through reduction operations such as sum or all-reduce, which combine partial computations from all processors into a unified global result, ensuring consistency in distributed environments. Load balancing is critical to distribute these partitions evenly across processors, preventing imbalances that could lead to idle time and suboptimal performance, particularly in systems with variable workload characteristics.[6][7] The benefits of data parallelism include enhanced scalability as dataset sizes grow, allowing additional processors to process larger volumes without linearly increasing execution time, and straightforward implementation for embarrassingly parallel problems—those requiring minimal inter-task communication, such as independent data transformations. It enables potential linear speedup, governed by Amdahl's law, which quantifies the theoretical maximum acceleration from parallelization. Amdahl's law is expressed as where is the fraction of the total computation that can be parallelized, and is the number of processors; this formula highlights how speedup approaches as increases, underscoring the importance of minimizing serial components for effective scaling.[6][8]Illustrative Example

To illustrate data parallelism, consider a simple scenario where the goal is to compute the sum of all elements in a large array, such as one containing 1,000 numerical values, using four processors.[9] The array is partitioned into four equal subsets of 250 elements each, with one subset assigned to each processor, exemplifying the principle of data partitioning where the workload is divided based on the data.[10] In the first step, data distribution occurs: Processor 1 receives elements 1 through 250, Processor 2 receives 251 through 500, Processor 3 receives 501 through 750, and Processor 4 receives 751 through 1,000.[11] Next, local computation takes place in parallel, with each processor independently summing the values in its assigned subset to produce a partial sum—for instance, Processor 1 might compute a partial sum of 12,500 from its elements.[9] The process then involves communication for aggregation: The four partial sums are combined using an all-reduce operation, where each processor shares its result with the others, and all processors collectively compute the total sum (e.g., 50,000 if the partial sums add up accordingly).[12] This yields the final result, the sum of the entire array, distributed across the processors for efficiency.[10] A descriptive flow of this process can be outlined as follows:- Initialization: Load the full array on a master node and broadcast the partitioning scheme to all processors.

- Distribution: Scatter subsets to respective processors (e.g., via a scatter operation).

- Parallel Summation: Each processor computes its local sum without inter-processor communication.

- Reduction: Gather partial sums and reduce them (e.g., via all-reduce) to obtain the global sum, then broadcast the result if needed.

Historical Development

Origins in Early Computing

In the mid-1960s, the theoretical foundations of data parallelism emerged within computer architecture classifications. Michael J. Flynn introduced his influential taxonomy in 1966, categorizing systems based on instruction and data streams, with the Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) class directly embodying data parallelism by applying one instruction to multiple data elements concurrently. This framework highlighted SIMD as a mechanism for exploiting inherent parallelism in array-based computations, distinguishing it from sequential single-data processing. Flynn's classification provided a conceptual blueprint for architectures that could handle bulk data operations efficiently, influencing subsequent designs in parallel computing.[14] Key theoretical insights into parallel processing limits further shaped early understandings of data parallelism. In 1967, Gene Amdahl published a seminal analysis arguing that while multiprocessor systems could accelerate parallelizable workloads, inherent sequential bottlenecks would cap overall gains, emphasizing the need to maximize the parallel fraction in data-intensive tasks.[15] Concurrently, programming paradigms began supporting data-parallel ideas through array-oriented languages. Kenneth E. Iverson's 1962 work on APL (A Programming Language established arrays as primitive types, enabling concise expressions for operations over entire datasets, such as vector additions or matrix transformations, which inherently promoted parallel evaluation.[16] Early proposals like Daniel Slotnick's SOLOMON project in 1962 laid groundwork for SIMD architectures. By the mid-1970s, hardware innovations realized these concepts in practice. The ILLIAC IV, operational from 1974, was the first massively parallel computer with up to 256 processing elements executing SIMD instructions on array data. The Cray-1 supercomputer, delivered in 1976, incorporated vector registers and pipelines that performed SIMD-like operations on streams of data, allowing scientific simulations to process large arrays in parallel for enhanced throughput in fields like fluid dynamics.[17] This vector processing capability marked an early milestone in hardware support for data parallelism, bridging theoretical models with tangible performance improvements in batch-oriented scientific workloads.Key Milestones and Evolution

The 1980s marked the rise of data parallelism through the development of massively parallel processors, exemplified by the Connection Machine introduced by Thinking Machines Corporation in 1985. This SIMD-based architecture enabled simultaneous operations on large datasets across thousands of simple processors, facilitating efficient data-parallel computations for applications like simulations and image processing.[18] Building on early SIMD concepts from vector processors, these systems demonstrated the scalability of data parallelism for handling massive data volumes in a single instruction stream.[19] In the 1990s, efforts toward standardization laid the groundwork for distributed data parallelism, culminating in the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard released in 1994 by the MPI Forum. MPI provided a portable framework for message-passing in parallel programs across clusters, enabling data partitioning and communication in distributed-memory environments.[20] The 1990s and 2000s saw further integration of data parallelism into high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, such as Beowulf systems built from commodity hardware, which scaled to thousands of nodes for parallel data processing.[21] GPU acceleration accelerated this evolution with NVIDIA's CUDA platform launched in 2006, allowing programmers to write data-parallel kernels that exploit thousands of GPU cores for tasks like matrix operations and scientific simulations.[22] The 2010s expanded data parallelism to large-scale distributed systems, influenced by big data frameworks such as Apache Hadoop, released in 2006, which implemented the MapReduce model for fault-tolerant parallel processing of petabyte-scale datasets across clusters. This was complemented by Apache Spark in 2010, which introduced in-memory data parallelism via Resilient Distributed Datasets (RDDs), enabling faster iterative computations over distributed data compared to disk-based approaches.[23] By the late 2010s and early 2020s, data parallelism evolved toward hybrid models integrating cloud computing, where frameworks like Spark and MPI facilitate elastic scaling across cloud resources for dynamic workloads. Standards advanced with OpenMP 5.0 in 2018, introducing enhanced support for task and data parallelism, including device offloading to accelerators and improved loop constructs for heterogeneous systems.[24]Implementation Approaches

Steps for Parallelization

To convert a sequential program into a data-parallel one, the process begins by analyzing the computational structure to ensure suitability for distribution across multiple processors, focusing on operations that can be applied uniformly to independent data subsets. This involves a systematic sequence of steps that emphasize data decomposition, resource allocation, and coordination to achieve efficient parallelism while minimizing overheads such as communication and synchronization costs.[6] The first step is to identify parallelizable portions of the program, particularly loops or iterations where computations on data elements are independent and can be executed without interdependencies. For instance, operations like element-wise array computations, as in summing an array, are ideal candidates since each data point can be processed separately. This identification requires profiling the code to locate computational hotspots and verify the absence of data races or sequential constraints.[6][25] Next, partition the data into subsets that can be distributed across processors, using methods such as block distribution—where contiguous chunks of data are assigned to each processor—or cyclic distribution, which interleaves data elements round-robin style to balance load and improve locality. Block partitioning suits regular access patterns, while cyclic helps mitigate imbalances in irregular workloads by ensuring even computational distribution. The choice depends on data size, access patterns, and hardware topology to optimize memory access and reduce contention.[26][25] Following partitioning, assign computations to processors by mapping data subsets to available compute units, ensuring that each processor handles its local portion with minimal global coordination. This mapping aligns data locality with processor architecture, such as assigning blocks to cores in a multicore system or nodes in a cluster, to maximize cache efficiency and pipeline utilization. Tools like MPI can facilitate this assignment through rank-based indexing.[7][6] Subsequently, implement communication mechanisms to exchange necessary data between processors, such as broadcasting shared inputs at the start or using gather and reduce operations to aggregate outputs like partial sums. These operations ensure consistency without excessive data movement; for example, in a distributed array sum, local results are reduced globally via summation. Efficient communication patterns, often via message-passing interfaces, are critical to avoid bottlenecks in distributed environments.[6][7] Finally, handle synchronization to coordinate processors and manage errors, employing barriers to ensure all tasks complete phases before proceeding and incorporating fault tolerance through checkpointing or redundancy to recover from failures. Barriers prevent premature access to incomplete data, while fault tolerance mechanisms like periodic saves maintain progress in long-running computations. This step safeguards correctness and reliability in scalable systems.[6][27] Success of data parallelization is evaluated using metrics like speedup—the ratio of sequential to parallel execution time—and efficiency, which accounts for resource utilization. These are bounded by Amdahl's law, which highlights that parallel gains are limited by the fraction of the program that remains sequential.[6]Programming Environments and Tools

Data parallelism implementations rely on a variety of programming environments and tools tailored to different hardware architectures and application scales. Traditional frameworks laid the groundwork for both distributed and shared-memory systems, while GPU-specific and modern distributed libraries have evolved to address the demands of large-scale computing, particularly in machine learning. The Message Passing Interface (MPI), first standardized in 1994 by the MPI Forum, serves as a foundational tool for distributed-memory data parallelism across clusters of computers. MPI enables explicit communication between processes, supporting data partitioning and synchronization through primitives like point-to-point sends/receives and collective operations such as MPI_Allreduce, which aggregates results from parallel computations.[28] This makes it suitable for domain decomposition approaches where data is divided among nodes, with implementations like MPICH and OpenMPI providing portable, high-performance support for scalability up to thousands of processes.[28] For shared-memory systems, OpenMP, introduced in 1997 as an API specification by a consortium including Intel and AMD, uses simple compiler directives to parallelize data-intensive loops on multi-core processors.[29] Key directives like#pragma omp parallel for distribute loop iterations across threads, implicitly handling data sharing and load balancing in a fork-join model.[29] OpenMP's directive-based approach minimizes code changes from serial programs, achieving good scalability on symmetric multiprocessors (SMPs) with low overhead for thread creation and synchronization.[29]

GPU-focused tools emerged to exploit the massive thread-level parallelism of graphics processing units. NVIDIA's Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA), released in 2006, provides a C/C++-like extension for writing kernels that execute thousands of threads in SIMD fashion over data arrays. CUDA's hierarchical model—organizing threads into blocks and grids—facilitates efficient data parallelism by mapping computations to the GPU's streaming multiprocessors, with built-in memory management for host-device data transfer.[30] This has enabled speedups of orders of magnitude for embarrassingly parallel workloads, though it is vendor-specific to NVIDIA hardware.[30]

Complementing CUDA, the Open Computing Language (OpenCL), standardized by the Khronos Group in 2009, offers a cross-vendor alternative for heterogeneous parallelism on GPUs, CPUs, and accelerators. OpenCL kernels define parallel work-items grouped into work-groups, supporting data parallelism through vectorized operations and shared local memory, with platform portability across devices from AMD, Intel, and others.[31] Its runtime API handles command queues and buffering, reducing overhead in multi-device setups.[31]

Modern distributed frameworks, particularly for machine learning, build on these foundations to simplify multi-node data parallelism. PyTorch's DistributedDataParallel (DDP), part of the torch.distributed backend introduced in 2017 and refined in versions up to 2.9.1 (2025), wraps neural network models for synchronous training across GPUs and nodes.[32] DDP automatically partitions minibatches, performs gradient all-reduce using NCCL or Gloo backends, and overlaps communication with computation to achieve near-linear scalability on clusters of up to hundreds of GPUs. PyTorch and TensorFlow support multi-GPU setups with heterogeneous NVIDIA GPUs like RTX 5090 and RTX 2080 Ti via DataParallel, DistributedDataParallel (DDP), or manual device assignment; this is possible despite differing VRAM or compute capabilities, though with warnings about memory imbalances requiring careful management.[33]

Additionally, PyTorch provides Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP), an advanced data-parallel technique that shards model parameters, optimizer states, and gradients across devices to significantly reduce per-device memory usage. This enables the training of very large models that exceed single-device memory capacity while maintaining the synchronization and scalability benefits of data parallelism. FSDP builds on DDP principles but adds sharding for memory efficiency, making it suitable for large-scale AI models.[34]

TensorFlow's tf.distribute API, launched in 2019 with TensorFlow 2.0, provides high-level strategies for data parallelism, including MirroredStrategy for intra-node multi-GPU replication and MultiWorkerMirroredStrategy for cross-node distribution.[35] It abstracts synchronization via collective ops like all-reduce, supporting fault tolerance and mixed-precision training with minimal code modifications.[35]

Horovod, open-sourced by Uber in 2017, extends data parallelism across frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow by integrating ring-allreduce algorithms over MPI or NCCL, enabling efficient gradient averaging with low bandwidth overhead.[36] Horovod's design emphasizes framework interoperability and elastic scaling, achieving up to 90% efficiency on large GPU clusters compared to single-node training.[37] As of 2025, however, Horovod is less actively maintained, with its last major release in 2023 and deprecation in certain platforms such as Azure Databricks.[38][39]

Among recent developments, Ray—initiated in 2016 by UC Berkeley researchers—incorporates data-parallel actors for stateful, distributed task execution, with updates from 2023 to 2025 enhancing fault-tolerant scaling for AI pipelines through improved actor scheduling and integration with Ray Train for parallel model training.[40][41] In October 2025, Ray was transferred to the PyTorch Foundation by Anyscale, enhancing its alignment with the broader PyTorch ecosystem.[42] Ray's actor model allows data-parallel operations on remote objects, supporting dynamic resource allocation across clusters.[40]

Dask, a flexible Python library for parallel computing since 2015, received enhancements through 2025, including in version 2025.11.0 with joint optimization for multiple Dask-Expr backed collections, optimized lazy evaluation for distributed arrays, and better GPU support via CuPy integration, streamlining data-parallel workflows in scientific computing.[43] These updates reduce scheduling overhead and improve interoperability with libraries like NumPy and Pandas for out-of-core data processing.[43]

Selecting among these tools involves evaluating trade-offs in communication overhead, scalability, and ease of use. Lower overhead, as in Horovod's ring-allreduce, minimizes latency in gradient synchronization for distributed training.[44] Scalability is assessed via metrics like strong scaling efficiency, where tools like MPI and DDP maintain performance up to thousands of nodes by balancing computation and communication.[44] Ease of use favors directive-based (OpenMP) or wrapper-style (DDP, tf.distribute) APIs that require few code alterations, enhancing developer productivity over low-level message passing.[45]