Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Declaration of Sentiments

View on Wikipedia

The Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,[1] is a document signed in 1848 by 68 women and 32 men—100 out of some 300 attendees at the first women's rights convention to be organized by women. Held in Seneca Falls, New York, the convention is now known as the Seneca Falls Convention. The principal author of the Declaration was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who modeled it upon the United States Declaration of Independence. She was a key organizer of the convention along with Lucretia Coffin Mott, and Martha Coffin Wright.

According to the North Star, published by Frederick Douglass, whose attendance at the convention and support of the Declaration helped pass the resolutions put forward, the document was the "grand movement for attaining the civil, social, political, and religious rights of women."[2][3]

Background

[edit]Early activism and the reform movements

[edit]In the early 1800s, women were largely relegated to domestic roles as mothers and homemakers, and were discouraged from participating in public life.[4] While they exercised a degree of economic independence in the colonial era, they were increasingly barred from meaningfully participating in the workforce and relegated to domestic and service roles near the turn of the 19th century.[5] Coverture laws also meant that women remained legally subordinated under their husbands.[6]

The decades leading up to the Seneca Falls Convention and the signing of the Declaration saw a small but steadily-growing movement pushing for women’s rights. Egalitarian ideas within the U.S. had already seen limited circulation in the years following the American Revolution, in the works of writers including James Otis and Charles Brockden Brown.[4] These sentiments began to emerge more widely with the advent of the Second Great Awakening, a period of Protestant revival and debate in the first half of the 19th century that led to widespread optimism and the development of various American reform movements.[7]

The first advocates for women’s rights, including Frances Wright and Ernestine Rose, were focused on improving economic conditions and marriage laws for women.[8] However, the growth of political reform movements, most notably the abolitionist movement, provided female activists with a platform from which they could effectively push for greater political rights and suffrage.[8] The involvement of women such as Angelina Grimke and her sister Sarah Moore in the anti-slavery campaigns attracted substantial controversy and divided abolitionists, but also laid the groundwork for active female participation in public affairs.[7]

A major catalyst for the women’s rights movement would come at the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. With a majority vote from the male attendees, American female delegates were barred from fully partaking in the proceedings. This experience, a vivid illustration of women’s status as second-class citizens, was what motivated prominent activists Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to begin advocating for women’s rights.[9]

By the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, the early women’s rights movement had already achieved several major political and legal successes. Marital legislative reforms and the repeal of coverture in several state jurisdictions such as New York was achieved through the introduction of Married Woman's Property Acts.[10] Women’s rights and suffrage also gained exposure when they were included in the 1848 platform of Liberty Party U.S. presidential candidate Gerrit Smith, the first cousin of Elizabeth Stanton.[11]

The Seneca Falls Convention

[edit]The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 was the first women’s rights conference in the United States. Held at the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Seneca Falls, New York, it was predominantly organised by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with the assistance of Lucretia Mott and local female Quakers.[12] Despite the relative inexperience of the organisers, the event attracted approximately 300 attendees, including around 40 men.[13] Among the dignitaries was the legendary slavery abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who argued eloquently for the inclusion of suffrage in the convention’s agenda.

“Nature has given woman the same powers, and subjected her to the same earth, breathes the same air, subsists on the same food, physical, moral, mental and spiritual. She has, therefore, an equal right with man, in all efforts to obtain and maintain a perfect existence.”[14]

Over two days, the attendees heard addresses from speakers including Stanton and Mott, voted on a number of resolutions and deliberated on the text of the Declaration. At the conclusion of the convention, the completed Declaration was signed by over 100 attendees, including 68 women and 32 men.[15]

Rhetoric

[edit]Overview

[edit]Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Rights and Sentiments utilises similar rhetoric to the United States Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson, a gesture which was neither an accident nor a submissive action.[16] Such a purposeful mimicking of language and form meant that Stanton tied together the complaints of women in America with the Declaration of Independence, in order to ensure that in the eyes of the American people, such requests were not seen as overly radical.[17]

Using Jefferson’s document as a model, Stanton also linked together the independence of America from Britain with the ‘patriarchy’ in order to emphasise how both were unjust forms of governance from which people needed to be freed.[18]

Therefore, through such a familiar phrasing of arguments and issues that the women of the new American republic were facing, Stanton’s use of Jefferson rhetoric can be seen as an attempt to deflect the hostility that women faced when calling for new socio-political freedoms, as well as to make the claims of women as “self-evident” as the rights given to men following from the gaining of independence from Britain.[19]

Specific examples

[edit]The foremost example of such mimicking of rhetoric is provided in the preamble of both texts. Stanton successfully manipulates Jefferson’s words, changing “all men are created equal” to “all men and women are created equal” where Stanton and the signatories of her declaration establish that women both hold and are deserving of “inalienable rights”.[18]

Stanton’s link between the Patriarchal government and the British rule over the American colonies is also at the forefront of the declaration, changing the words in Jefferson’s document from “Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government” to “Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled”. Such a slight change to rhetoric, ensured the continuous linkage between the struggles entwined within both declarations.[20]

Further changes to the demands of the original Declaration of independence also occurred, as Stanton places forward her arguments for greater socio-political freedoms for women. Stantons’ manifesto, mimicking the form of the Declaration of Independence, protests the poor condition of women’s education, women’s position in the church and the exclusion of women from employment in a similar manner to which Jefferson’s original Declaration protests the British governance of the colonies.[21]

Effects of rhetoric

[edit]The direct effects of Stanton’s use of Jefferson’s rhetoric on people of the time, is unquantifiable. However, whilst Stanton had an intended effect in mind, the reality is that the use of the similar rhetoric was not as effective as was hoped, as only around 100 of the 300 men and women who attended the convention eventually ended up signing the document.[22]

Furthermore, whilst Stanton intended for changes to be made immediately after the Seneca Falls Convention, it was the ending of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Period before women's rights movements become increasingly mainstream and actual change was effected.[23]

Opening paragraphs

[edit]When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these rights, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed, but when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpation on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.[24]

Sentiments

[edit]- He has not ever permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

- He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

- He has withheld her from rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners.

- Having deprived her of this first right as a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

- He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

- He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

- He has made her morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

- He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce, in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given; as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of the women—the law, in all cases, going upon a false supposition of the supremacy of a man, and giving all power into his hands.

- After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

- He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

- He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

- He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education—all colleges being closed against her.

- He allows her in church, as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church.

- He has created a false public sentiment by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

- He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

- He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Closing remarks

[edit]Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation—in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States. In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

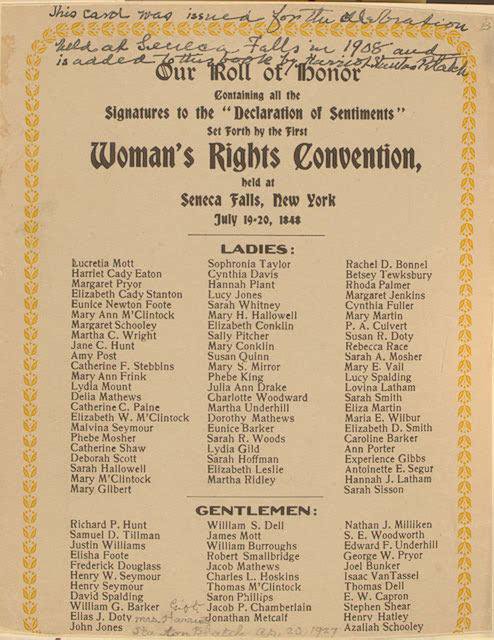

Signatories

[edit]Signers of the Declaration at Seneca Falls in order:[25]

- Lucretia Mott (1793–1880)[26]

- Harriet Cady Eaton (1810–1894) - sister of Elizabeth Cady Stanton[27]

- Margaret Pryor (1785–1874) - Quaker reformer[28]

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902)[29]

- Eunice Newton Foote (1819–1888)

- Mary Ann M'Clintock (1800–1884) - Quaker reformer, half-sister of Margaret Pryor[30]

- Margaret Schooley (1806–1900)

- Martha C. Wright (1806–1875) - Quaker reformer, sister of Lucretia Mott[31]

- Jane C. Hunt (1812–1889)[32]

- Amy Post (1802–1889)[33]

- Catherine F. Stebbins (1823–1904)

- Mary Ann Frink

- Lydia Hunt Mount (c. 1800–1868) - well-off Quaker widow[34]

- Delia Matthews (1797–1883)

- Catharine V. Paine (1829–1908)[35] - 18 years old at the time, she is likely one of two signers of the Declaration of Sentiments to have cast a ballot.[36] Catharine Paine Blaine registered to vote in Seattle in 1885 after Washington Territory extended voting rights to women in 1883, making her the first female signer of the Declaration of Sentiments to legally register as a voter.[35]

- Elizabeth W. M'Clintock (1821–1896) - daughter of Mary Ann M'Clintock. She invited Frederick Douglass to attend.[37]

- Malvina Beebe Seymour (1818–1903)

- Phebe Mosher

- Catherine Shaw

- Deborah Scott

- Sarah Hallowell

- Mary M'Clintock (1822–) - daughter of Mary Ann M'Clintock[38]

- Mary Gilbert

- Sophrone Taylor

- Cynthia Davis[39]

- Hannah Plant (c. 1795–)[40]

- Lucy Jones

- Sarah Whitney

- Mary H. Hallowell

- Elizabeth Conklin (c. 1812–1884)

- Sally Pitcher

- Mary Conklin (1829–1909)

- Susan Quinn (1834–1909)

- Mary S. Mirror

- Phebe King[41]

- Julia Ann Drake (c. 1814–)[42]

- Charlotte Woodward (1830–1924) - the only signer who lived to see the 19th amendment though illness apparently prevented her from ever voting.[43]

- Martha Underhill (1806–1872) - her nephew also signed

- Dorothy Matthews (c. 1804–1875)

- Eunice Barker

- Sarah R. Woods

- Lydia Gild

- Sarah Hoffman

- Elizabeth Leslie

- Martha Ridley

- Rachel D. Bonnel (1827–1909)[44]

- Betsey Tewksbury (c. 1814–after 1880)

- Rhoda Palmer (1816–1919) - the only woman signer who ever legally voted, in 1918 when New York passed female suffrage.[45]

- Margaret Jenkins[46]

- Cynthia Fuller

- Mary Martin

- P.A. Culvert

- Susan R. Doty

- Rebecca Race (1808–1895)[47]

- Sarah A. Mosher

- Mary E. Vail (1827–1910) - daughter of Lydia Mount[48]

- Lucy Spalding

- Lavinia Latham (1781–1859)[49]

- Sarah Smith

- Eliza Martin

- Maria E. Wilbur

- Elizabeth D. Smith

- Caroline Barker

- Ann Porter

- Experience Gibbs (c. 1822–1899)

- Antoinette E. Segur

- Hannah J. Latham - daughter of Lavinia Latham

- Sarah Sisson

- The following men signed, under the heading "...the gentlemen present in favor of this new movement":

- Richard P. Hunt (1797–1856) - husband of Jane C. Hunt, brother of Lydia Mount and Hannah Plant, all also signers[50]

- Samuel D. Tillman (1813/5–1875)

- Justin Williams (1813–1878)

- Elisha Foote (1809–1883) - spouse of Eunice Newton Foote

- Frederick Douglass (c. 1818–1895)[51]

- Henry W. Seymour (1814–1895) - spouse of Malvina Beebe Seymour, a signer

- Henry Seymour (1803–1878)

- David Spalding (1792–1867) - spouse of Lucy Spalding

- William G. Barker (1809–1897) - spouse of Caroline Barker, a signer

- Elias J. Doty

- John Jones

- William S. Dell (1801–1865) - uncle of Rachel Dell Bonnel, a signer[52]

- James Mott (1788–1868) - husband of Lucretia Mott[53]

- William Burroughs (1828–1901)

- Robert Smalldridge (1820–1899)

- Jacob Matthews (1805–1874)

- Charles L. Hoskins

- Thomas M'Clintock (1792–1876) - husband of Mary Ann M'Clintock[54]

- Saron Phillips

- Jacob Chamberlain (1802–1878) - Methodist Episcopal and later a member of the US House of Representatives[55]

- Jonathan Metcalf

- Nathan J. Milliken

- S.E. Woodworth (1814–1887)

- Edward F. Underhill (1830–1898) - his aunt was Martha Barker Underhill, a signer[56]

- George W. Pryor - son of Margaret Pryor who also signed[57]

- Joel Bunker

- Isaac Van Tassel (1812–1889)

- Thomas Dell (1828–1851) - son of William S. Dell and cousin of Rachel Dell Bonnel, both signers[58]

- E.W. Capron (c. 1820–1892)

- Stephen Shear

- Henry Hatley

- Azaliah Schooley (c. 1805–1855) Spouse of Margaret Schooley. Born in Lincoln County, Upper Canada, and naturalized as an American citizen in 1837. A resident of Waterloo, New York, and member of the Junius Monthly Meeting. Also had ties to Spiritualist and Abolition movements.[59][60]

See also

[edit]- Legal rights of women

- Coverture

- Women's Rights National Historical Park - includes the site of the convention, and other, related sites

- National Women's Hall of Fame - established near the site of the convention

- Feminism

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Timeline of women's suffrage

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Library of Congress. The Learning Page. Lesson Two: Changing Methods and Reforms of the Woman's Suffrage Movement, 1840-1920. "The first convention ever called to discuss the civil and political rights of women...(excerpt)". Retrieved on April 4, 2009.

- ^ North Star, July 28, 1848, as quoted in Frederick Douglass on Women's Rights, Philip S. Foner, ed. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992, pp. 49-51; originally published in 1976

- ^ Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Susan B. Anthony; Matilda Joslyn Gage; Ida Husted Harper, eds. (1881). History of Woman Suffrage: 1848-1861. Vol. 1. New York: Fowler & Wells. p. 74.

- ^ a b Vietto, Angela (2006). Women and Authorship in Revolutionary America (1st ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

- ^ Locke, Joseph; Wight, Ben, eds. (2019). "Religion and Reform". The American Yawp. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Hoff, Joan (1991). Law, Gender and Injustice: A Legal History of U.S. Women. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Garvey, T. Gregory (2006). Creating the Culture of Reform in Antebellum America. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press.

- ^ a b DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998). Woman Suffrage and Womens Rights. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 83–84.

- ^ McMillen, Sally Gregory (2008). Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 72–77.

- ^ Hoff, Joan (1991). Law, Gender and Injustice: A Legal History of U.S. Women. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 121–124.

- ^ Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 176. ISBN 0252029046.

- ^ Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 184–191.

- ^ Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 192–196.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (2012). McKivigan, John R; Kaufman, Heather L (eds.). In the Words of Frederick Douglass: Quotations from Liberty's Champion. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- ^ Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 196–202.

- ^ Joan Hoff, Law, Gender and Injustice: A Legal History of U.S. Women (New York: New York University Press, 1991), 138.

- ^ Linda K. Kerber, “FROM THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TO THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS: THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC 1776-1848,” Human Rights 6, no, 2 (1977): 115.

- ^ a b Joan Hoff, Law, Gender and Injustice: A Legal History of U.S. Women (New York: New York University Press, 1991), 76.

- ^ Kerber, “DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS.” 116.

- ^ Penny A Weiss, Feminist Manifestos: A Global Documentary Reader (New York: NYU Press, 2018), 76.

- ^ Kerber, Linda K. “FROM THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TO THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS: THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC 1776-1848.” Human Rights 6, no. 2 (1977): 116

- ^ “Signatures to the ‘Declaration of Rights and Sentiments’,” United States Census Bureau, accessed October 25, 2022, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sis/resources/historical-documents/declaration-sentiments.html

- ^ Hoff, Law, Gender and Injustice,140.

- ^ "Modern History Source book: Seneca Falls: The Declaration of Sentiments, 1848".

- ^ "Signers of the Declaration of Sentiments". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Lucretia Mott - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Harriet Cady Eaton - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Margaret Wilson Pryor - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Elizabeth Cady Stanton - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Mary Ann M'Clintock - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Martha C. Wright - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Jane Hunt - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Amy Post - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Lydia Mount - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ a b Stevenson, Shanna. "Catharine Paine Blaine" (PDF). Washington State Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-29. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ "Catharine Paine Blaine". Washington State Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01.

- ^ "Elizabeth M'Clintock - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Mary M'Clintock". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Cynthia Davis - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Hannah Plant - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Phebe King - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Julia Ann Drake - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Charlotte Woodward". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Rachel Dell Bonnel - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Rhoda Palmer". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Margaret Jenkins - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Rebecca Race - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Mary E. Vail - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Lavinia Latham - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Richard P. Hunt - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Frederick Douglass - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "William S. Dell - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "James Mott - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Thomas M'Clintock - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Jacob P. Chamberlain - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Edward Fitch Underhill - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "George W. Pryor - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "Thomas Dell - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ ""Obituary - Azaliah Schooley."". The Liberator. 23 November 1855.

- ^ Schooley, Azaliah. ""Letter to Isaac Post"". Retrieved June 20, 2018.

Bibliography

- "The Rights of Women", The North Star" (July 28, 1848)

- "Bolting Among the Ladies", Oneida Whig (August 1, 1848)

- Tanner, John. "Women out of their Latitude" Mechanics' Mutual Protection (1848)