Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

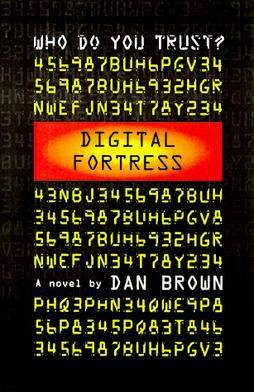

Digital Fortress

View on Wikipedia

Digital Fortress is a techno-thriller novel written by American author Dan Brown and published in 1998 by St. Martin's Press. The book explores the theme of government surveillance of electronically stored information on the private lives of citizens, and the possible civil liberties and ethical implications of using such technology.

Key Information

Plot summary

[edit]The story is set in 1996. When the United States National Security Agency's (NSA) code-breaking supercomputer TRANSLTR encounters a revolutionary new code, Digital Fortress, that it cannot break, Commander Trevor Strathmore calls in head cryptographer Susan Fletcher to crack it. She is informed by Strathmore that it was written by Ensei Tankado, a former NSA employee who became displeased with the NSA's intrusion into people's private lives. If the NSA doesn't reveal TRANSLTR to the public, Tankado intends to auction the code's algorithm on his website and have his partner, "North Dakota", release it for free if he dies, essentially holding the NSA hostage. Strathmore tells Fletcher that Tankado has in fact died in Seville at the age of 32, of what appears to be a heart attack. Strathmore intends to keep Tankado's death a secret because if Tankado's partner finds out, he will upload the code. The agency is determined to stop Digital Fortress from becoming a threat to national security.

Strathmore asks Fletcher's fiancé David Becker to travel to Seville and recover a ring that Tankado was wearing when he died. The ring is suspected to have the passcode that unlocks Digital Fortress. However, Becker soon discovers that Tankado gave the ring away just before his death. Unbeknown to Becker, a mysterious figure, named Hulohot, follows him, and murders each person he questions in the search for the ring. Unsurprisingly, Hulohot's final attempt would be on Becker himself.

Meanwhile, telephone calls between North Dakota and Tokugen Numataka reveal that North Dakota hired Hulohot to kill Tankado in order to gain access to the passcode on his ring and speed up the release of the algorithm.

At the NSA, Fletcher's investigation leads her to believe that Greg Hale, a fellow NSA employee, is North Dakota. Phil Chartrukian, an NSA technician who is unaware of the Digital Fortress code breaking failure and believes Digital Fortress to be a virus, conducts his own investigation into whether Strathmore allowed Digital Fortress to bypass Gauntlet, the NSA's virus/worm filter. To save the TRANSLTR Phil decides to shut it down but is murdered after being pushed off sub-levels of TRANSLTR by an unknown assailant. Since Hale and Strathmore were both in the sub-levels, Fletcher assumes that Hale is the killer; however, Hale claims that he witnessed Strathmore killing Chartrukian. Chartrukian's fall also damages TRANSLTR's cooling system.

Hale holds Fletcher and Strathmore hostage to prevent himself from being arrested for Phil's murder. It is then that Hale explains to Fletcher, the e-mail he supposedly received from Tankado was also in Strathmore's inbox, as Strathmore was snooping on Tankado. Fletcher discovers through a tracer that North Dakota and Ensei Tankado are the same person, as "NDAKOTA" is an anagram of "Tankado."

Strathmore kills Hale and arranges it to appear as a suicide. Fletcher later discovers through Strathmore's pager that he is the one who hired Hulohot. Becker manages to track down the ring, but ends up pursued by Hulohot in a long cat-and-mouse chase across Seville. The two eventually face off in a cathedral, where Becker finally kills Hulohot by tripping him down a spiral staircase, causing him to break his neck. He is then intercepted by NSA field agents sent by Leland Fontaine, the director of the NSA.

Chapters told from Strathmore's perspective reveal his master plan. By hiring Hulohot to kill Tankado, having Becker recover his ring and at the same time arranging for Hulohot to kill Becker, he would facilitate a romantic relationship with Fletcher, regaining his lost honor. He has also been working incessantly for many months to unlock Digital Fortress, installing a backdoor inside the program. By making phone calls to Numataka posing as North Dakota, he thought he could partner with Numatech to make a Digital Fortress chip equipped with his own backdoor Trojan. Finally, he would reveal to the world the existence of TRANSLTR, boasting it would be able to crack all the codes except Digital Fortress, making everyone rush to use the computer chip equipped with Digital Fortress so that the NSA could spy on every computer equipped with these chips.

However, Strathmore was unaware that Digital Fortress is actually a computer worm that, once unlocked would "eat away" all the NSA databank's security and allow "any third-grader with a modem" to look at government secrets. When TRANSLTR overheats, Strathmore dies by standing next to the machine as it explodes. The worm eventually gets into the database, but Becker figures out the passcode just seconds before the last defenses fall (3, which is the difference between the Hiroshima nuclear bomb, Isotope 235, and the Nagasaki nuclear bomb, isotope 238, a reference to the nuclear bombs that killed Tankado's mother and left him crippled), and Fletcher is able to terminate the worm before hackers can get any significant data. The NSA allows Becker to return to the United States, reuniting him with Fletcher.

In the epilogue, it is revealed that Numataka was Ensei Tankado's father who left Tankado the day he was born due to Tankado's deformity. As Tankado's last living relative, Numataka inherits the rest of Tankado's possessions.

Characters

[edit]- Susan Fletcher – The NSA's Head Cryptographer, and the story's lead character

- David Becker – A Professor of Modern Languages and the fiancé of Susan Fletcher

- Ensei Tankado – The author of Digital Fortress and a disgruntled former NSA employee.

- Commander Trevor Strathmore – NSA Deputy Director of Operations, second commander in chief

- Phil Chartrukian – NSA Technician

- Greg Hale – NSA Cryptographer

- Leland Fontaine – Director of NSA

- Hulohot – an assassin hired by Strathmore to locate the Passkey

- Midge Milken – Fontaine's internal security analyst

- Chad Brinkerhoff – Fontaine's personal assistant

- "Jabba" – NSA's senior System Security Officer

- Soshi Kuta – Jabba's head technician and assistant

- Tokugen Numataka – Chairman of Japanese company Numatech attempting to purchase Digital Fortress. It is revealed in the Epilogue that Numataka is Tankado's father

Inaccuracies and criticism

[edit]The book was criticized by GCN for portraying facts about the NSA incorrectly and for misunderstanding the technology in the book, especially for the time when it was published.[1]

In 2005, the town hall of the Spanish city of Seville invited Dan Brown to visit the city, in order to dispel the inaccuracies about Seville that Brown represented within the book.[2]

Although uranium-235 was used in the bomb on Hiroshima, the nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki used plutonium-239 (created from U-238). Uranium-238 is non-fissile.

Julius Caesar's cypher was not as simple as the one described in the novel, based on square numbers. In The Code Book by Simon Singh it is described as a transposition cypher which was undecipherable until centuries later.

The story behind the meaning of "sincere" is based on false etymology.[3]

It is also untrue that in Spain (or in any other Catholic country) that the Holy Communion takes place at the beginning of Mass; Communion takes place very near the end.

In 2020, the book was featured on the podcast 372 Pages We'll Never Get Back, which critiques literature deemed low-quality.

Television adaptation

[edit]Imagine Entertainment announced in 2014 that it is set to produce a television series based on Digital Fortress, to be written by Josh Goldin and Rachel Abramowitz.[4]

Translations

[edit]Digital Fortress has been widely translated:

- Estonian as Digitaalne Kindlus

- Azerbaijani as Rəqəmsal Qala, ISBN 978-9952-26-426-5

- French as Forteresse Digitale, ISBN 978-2-253-12707-9

- Arabic as الحصن الرقمي, ISBN 9953299129, 2005, Arab Scientific Publishers

- Dutch as Het Juvenalis Dilemma, ISBN 9789024553020

- Korean as 디지털 포트리스

- German as Diabolus, ISBN 978-3785721940

- Bosnian as Digitalna tvrđava

- Portuguese as Fortaleza Digital, ISBN 972-25-1469-5

- Indonesian as Benteng Digital, ISBN 9791600910

- Turkish as Dijital Kale, ISBN 978-975-21-1165-3

- Danish as Tankados Kode

- Hebrew as שם הצופן: מבצר דיגיטלי

- Slovak as Digitálna pevnosť, ISBN 80-7145-9917

- Bulgarian as Цифрова крепост, ISBN 978-954-584-0173

- Hungarian as Digitális erőd, ISBN 978-963-689-3460

- Vietnamese as Pháo đài số, ISBN 978-604-50-2946-6

- Greek as ΨΗΦΙΑΚΟ ΟΧΥΡΟ, ISBN 960-14-1101-1

- Serbian as Дигитална тврђава

- Persian as قلعهی دیجیتالی

- Macedonian as Дигитална тврдина

- Russian as Цифровая крепость

- Spanish as La Fortaleza Digital, ISBN 8489367019

- Romanian as Fortăreața digitală

- Czech as Digitální pevnost

- Ukrainian as Цифрова фортеця

- Finnish as Murtamaton linnake

- Swedish as Gåtornas Palats, ISBN 9789100107161

- Norwegian as Den Digitale Festning

- Italian as Crypto, ISBN 978-880-45-7191-9

- Polish as Cyfrowa twierdza, ISBN 978-83-7885-752-5

- Albanian as Diabolus

- Traditional Chinese as 數位密碼

- Simplified Chinese as 数字城堡

- Slovene as Digitalna trdnjava

- Lithuanian as Skaitmeninė tvirtovė ISBN 978-9955-13-464-0

- Japanese as パズル・パレス

- Uzbek as Raqamli Qal’a

- Croatian as Digitalna tvrđava

- Marathi as Digital Fortress

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Breen II, John (August 2, 2011). "Why can't novels get technology right?". GCN. United States: Public Sector Media Group. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Nash, Elizabeth (August 27, 2005). "Dan Brown: Seville smells and is corrupt. City: You come here and say that". The Independent. United Kingdom. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Sincere | Search Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (September 11, 2014). "ABC Nabs Adaptation Of Dan Brown's 'Digital Fortress' From Imagine & 20th TV". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

External links

[edit]Digital Fortress

View on GrokipediaDigital Fortress is a techno-thriller novel written by American author Dan Brown and published in 1998 by St. Martin's Press.[1][2] The narrative centers on the National Security Agency (NSA), where the agency's supercomputer TRANSLTR, designed for decrypting global communications, confronts an unbreakable encryption algorithm devised by a disillusioned mathematician, precipitating a high-stakes conspiracy involving blackmail, betrayal, and international intrigue.[1][3] Protagonist Susan Fletcher, the NSA's head cryptographer, navigates internal deceptions and external threats to avert the exposure of classified data, highlighting tensions between governmental surveillance capabilities and individual privacy in the emerging digital era.[4] As Brown's debut novel for adult audiences, it established his signature blend of cryptographic puzzles, fast-paced action, and speculative intelligence operations, though it drew critique for implausible technical details and formulaic characterizations.[5] The work gained broader readership following the commercial triumph of Brown's subsequent The Da Vinci Code, underscoring its role in launching his career amid evolving public discourse on code-breaking ethics and data security.[2]