Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Persian language

View on Wikipedia

| Persian | |

|---|---|

| فارسی fārsī | |

Fārsi written in Persian calligraphy (Nastaʿlīq) | |

| Pronunciation | [fɒːɾˈsiː] ⓘ |

| Native to |

|

| Ethnicity | Persians, and other ethnicities in Iran and countries bordering it |

| Speakers | L1: 91 million (2023–2024)[8] L2: 35 million (2020–2023)[8] Total: 127 million (2020–2024)[8] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects | |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Russia |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fa |

| ISO 639-2 | per (B) fas (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | fas – inclusive codeIndividual codes: pes – Iranian Persianprs – Daritgk – Tajik languageaiq – Aimaq dialectbhh – Bukhori dialecthaz – Hazaragi dialectjpr – Judeo-Persianphv – Pahlavanideh – Dehwarijdt – Judeo-Tatttt – Caucasian Tat |

| Glottolog | fars1254 |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAC (Wider Persian) > 58-AAC-c (Central Persian) |

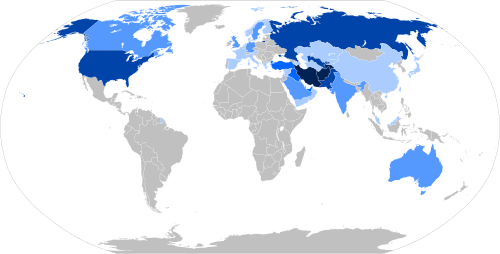

Areas with significant numbers of people whose first language is Persian (including dialects) | |

Persian linguasphere Legend Official language

More than 1,000,000 speakers

Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 speakers

Between 100,000 and 500,000 speakers

Between 25,000 and 100,000 speakers

Fewer than 25,000 speakers to none | |

Persian,[a] also known by its endonym Parsi / Farsi,[b] is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken and used officially within Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan in three mutually intelligible standard varieties, respectively Iranian Persian (officially known as Persian),[12][13][14] Dari Persian (officially known as Dari since 1964),[15] and Tajiki Persian (officially known as Tajik since 1999).[16][17] It is also spoken natively in the Tajik variety by a significant population within Uzbekistan,[2][18][19] as well as within other regions with a Persianate history in the cultural sphere of Greater Iran. It is written officially within Iran and Afghanistan in the Persian alphabet, a derivative of the Arabic script, and within Tajikistan in the Tajik alphabet, a derivative of the Cyrillic script.

Modern Persian is a continuation of Middle Persian, an official language of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE), itself a continuation of Old Persian, which was used in the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE).[20][21] It originated in the region of Fars (Persia) in southwestern Iran.[22] Its grammar is similar to that of many European languages.[23]

Throughout history, Persian was considered prestigious by various empires centered in West Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia.[24] Old Persian is attested in Old Persian cuneiform on inscriptions from between the 6th and 4th century BC. Middle Persian is attested in Aramaic-derived scripts (Pahlavi and Manichaean) on inscriptions and in Zoroastrian and Manichaean scriptures from between the third to the tenth centuries (see Middle Persian literature). New Persian literature was first recorded in the ninth century, after the Muslim conquest of Persia, since then adopting the Perso-Arabic script.[25]

Persian was the first language to break through the monopoly of Arabic on writing in the Muslim world, with Persian poetry becoming a tradition in many eastern courts.[24] It was used officially as a language of bureaucracy even by non-native speakers, such as the Ottomans in Anatolia,[26] the Mughals in South Asia, and the Pashtuns in Afghanistan. It influenced languages spoken in neighboring regions and beyond, including other Iranian languages, the Turkic, Armenian, Georgian, & Indo-Aryan languages. It also exerted some influence on Arabic,[27] while borrowing a lot of vocabulary from it in the Middle Ages.[20][23][28][29][30][31]

Some of the world's most famous pieces of literature from the Middle Ages, such as the Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, the works of Rumi, the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the Panj Ganj of Nizami Ganjavi, The Divān of Hafez, The Conference of the Birds by Attar of Nishapur, and the miscellanea of Gulistan and Bustan by Saadi Shirazi, are written in Persian.[32] Some of the prominent modern Persian poets were Nima Yooshij, Ahmad Shamlou, Simin Behbahani, Sohrab Sepehri, Rahi Mo'ayyeri, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Forugh Farrokhzad.

There are approximately 130 million Persian speakers worldwide, including Persians, Lurs, Tajiks, Hazaras, Iranian Azeris, Iranian Kurds, Balochs, Tats, Afghan Pashtuns, and Aimaqs. The term Persophone might also be used to refer to a speaker of Persian.[33][34]

Classification

[edit]Persian is a member of the Western Iranian group of the Iranian languages, which make up a branch of the Indo-European languages in their Indo-Iranian subdivision. The Western Iranian languages themselves are divided into two subgroups: Southwestern Iranian languages, of which Persian is the most widely spoken, and Northwestern Iranian languages, of which Kurdish and Balochi are the most widely spoken.[35]

Name

[edit]The term Persian is an English derivation of Latin Persiānus, the adjectival form of Persia, itself deriving from Greek Persís (Περσίς),[36] a Hellenized form of Old Persian Pārsa (𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿),[37] which means "Persia" (a region in southwestern Iran, corresponding to modern-day Fars). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term Persian as a language name is first attested in English in the mid-16th century.[38]

Farsi, which is the Persian word for the Persian language, has also been used widely in English in recent decades, more often to refer to Iran's standard Persian. However, the name Persian is still more widely used. The Academy of Persian Language and Literature has maintained that the endonym Farsi is to be avoided in foreign languages, and that Persian is the appropriate designation of the language in English, as it has the longer tradition in western languages and better expresses the role of the language as a mark of cultural and national continuity.[39] Iranian historian and linguist Ehsan Yarshater, founder of the Encyclopædia Iranica and Columbia University's Center for Iranian Studies, mentions the same concern in an academic journal on Iranology, rejecting the use of Farsi in foreign languages.[40]

Etymologically, the term Farsi derives from its earlier form Pārsi (Pārsik in Middle Persian), which in turn comes from the same root as the English term Persian.[41] In the same process, the Middle Persian toponym Pārs ("Persia") evolved into the modern name Fars.[42] The phonemic shift from /p/ to /f/ is due to the influence of Arabic in the Middle Ages, from the lack of the phoneme /p/ in Standard Arabic.[43][44][45][46]

Standard varieties' names

[edit]The standard Persian of Iran has been called, apart from Persian and Farsi, by names such as Iranian Persian and Western Persian, exclusively.[47][48] The official language of Iran is designated simply as Persian (فارسی, fārsi).[10]

The standard Persian of Afghanistan has been officially named Dari (دری, dari) since 1958.[15] Also referred to as Afghan Persian in English, it is one of Afghanistan's two official languages, together with Pashto. The term Dari, meaning "of the court", originally referred to the variety of Persian used in the court of the Sasanian Empire in capital Ctesiphon, which spread to the northeast of the empire and gradually replaced the former Iranian dialects of Parthia (Parthian).[49][50]

Tajik Persian (форси́и тоҷикӣ́, forsi-i tojikī), the standard Persian of Tajikistan, has been officially designated as Tajik (тоҷикӣ, tojikī) since the time of the Soviet Union.[17] It is the name given to the varieties of Persian spoken in Central Asia in general.[51]

ISO codes

[edit]The international language-encoding standard ISO 639-1 uses the code fa for the Persian language, as its coding system is mostly based on the native-language designations. The more detailed standard ISO 639-3 uses the code fas for the dialects spoken across Iran and Afghanistan.[52] This consists of the individual languages Dari (prs) and Iranian Persian (pes). It uses tgk for Tajik, separately.[53]

History

[edit]In general, the Iranian languages are known from three periods: namely Old, Middle, and New (Modern). These correspond to three historical eras of Iranian history; Old era being sometime around the Achaemenid Empire (i.e., 400–300 BC), Middle era being the next period most officially around the Sasanian Empire, and New era being the period afterward down to present day.[54]

According to available documents, the Persian language is "the only Iranian language"[20] for which close philological relationships between all of its three stages are established and so that Old, Middle, and New Persian represent[20][55] one and the same language of Persian; that is, New Persian is a direct descendant of Middle and Old Persian.[55] Gernot Windfuhr considers new Persian as an evolution of the Old Persian language and the Middle Persian language[56] but also states that none of the known Middle Persian dialects is the direct predecessor of Modern Persian.[57][58] Ludwig Paul states: "The language of the Shahnameh should be seen as one instance of continuous historical development from Middle to New Persian."[59]

The known history of the Persian language can be divided into the following three distinct periods:

Old Persian

[edit]

As a written language, Old Persian is attested in royal Achaemenid inscriptions. The oldest known text written in Old Persian is from the Behistun Inscription, dating to the time of King Darius I (reigned 522–486 BC).[60][citation not found] Examples of Old Persian have been found in what is now Iran, Romania (Gherla),[61][62][63] Armenia, Bahrain, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt.[64][65] Old Persian is one of the earliest attested Indo-European languages.[66]

According to certain historical assumptions about the early history and origin of ancient Persians in Southwestern Iran (where Achaemenids hailed from), Old Persian was originally spoken by a tribe called Parsuwash, who arrived in the Iranian Plateau early in the 1st millennium BCE and finally migrated down into the area of present-day Fārs province. Their language, Old Persian, became the official language of the Achaemenid kings.[66] Assyrian records, which in fact appear to provide the earliest evidence for ancient Iranian (Persian and Median) presence on the Iranian Plateau, give a good chronology but only an approximate geographical indication of what seem to be ancient Persians. In these records of the 9th century BCE, Parsuwash (along with Matai, presumably Medians) are first mentioned in the area of Lake Urmia in the records of Shalmaneser III.[67] The exact identity of the Parsuwash is not known for certain, but from a linguistic viewpoint the word matches Old Persian pārsa itself coming directly from the older word *pārćwa.[67] Also, as Old Persian contains many words from another extinct Iranian language, Median, according to P. O. Skjærvø it is probable that Old Persian had already been spoken before the formation of the Achaemenid Empire and was spoken during most of the first half of the first millennium BCE.[66] Xenophon, a Greek general serving in some of the Persian expeditions, describes many aspects of Armenian village life and hospitality in around 401 BCE, which is when Old Persian was still spoken and extensively used. He relates that the Armenian people spoke a language that to his ear sounded like the language of the Persians.[68]

Related to Old Persian, but from a different branch of the Iranian language family, was Avestan, the language of the Zoroastrian liturgical texts.

Middle Persian

[edit]

The complex grammatical conjugation and declension of Old Persian yielded to the structure of Middle Persian in which the dual number disappeared, leaving only singular and plural, as did gender. Middle Persian developed the ezāfe construction, expressed through ī (modern e/ye), to indicate some of the relations between words that have been lost with the simplification of the earlier grammatical system.

Although the "middle period" of the Iranian languages formally begins with the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, the transition from Old to Middle Persian had probably already begun before the 4th century BC. However, Middle Persian is not actually attested until 600 years later when it appears in the Sassanid era (224–651 AD) inscriptions, so any form of the language before this date cannot be described with any degree of certainty. Moreover, as a literary language, Middle Persian is not attested until much later, in the 6th or 7th century. From the 8th century onward, Middle Persian gradually began yielding to New Persian, with the middle-period form only continuing in the texts of Zoroastrianism.

Middle Persian is considered to be a later form of the same dialect as Old Persian.[69] The native name of Middle Persian was Parsig or Parsik, after the name of the ethnic group of the southwest, that is, "of Pars", Old Persian Parsa, New Persian Fars. This is the origin of the name Farsi as it is today used to signify New Persian. Following the collapse of the Sassanid state, Parsik came to be applied exclusively to (either Middle or New) Persian that was written in the Arabic script. From about the 9th century onward, as Middle Persian was on the threshold of becoming New Persian, the older form of the language came to be erroneously called Pahlavi, which was actually but one of the writing systems used to render both Middle Persian as well as various other Middle Iranian languages. That writing system had previously been adopted by the Sassanids (who were Persians, i.e. from the southwest) from the preceding Arsacids (who were Parthians, i.e. from the northeast). While Ibn al-Muqaffa' (eighth century) still distinguished between Pahlavi (i.e. Parthian) and Persian (in Arabic text: al-Farisiyah) (i.e. Middle Persian), this distinction is not evident in Arab commentaries written after that date.

New Persian

[edit]

"New Persian" (also referred to as Modern Persian) is conventionally divided into three stages:

- Early New Persian (8th/9th centuries)

- Classical Persian (10th–18th centuries)

- Contemporary Persian (19th century to present)

Early New Persian remains largely intelligible to speakers of Contemporary Persian, as the morphology and, to a lesser extent, the lexicon of the language have remained relatively stable.[70]

Early New Persian

[edit]New Persian texts written in the Arabic script first appear in the 9th-century.[71] The language is a direct descendant of Middle Persian, the official, religious, and literary language of the Sasanian Empire (224–651).[72] However, it is not descended from the literary form of Middle Persian (known as pārsīg, commonly called Pahlavi), which was spoken by the people of Fars and used in Zoroastrian religious writings. Instead, it is descended from the dialect spoken by the court of the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon and the northeastern Iranian region of Khorasan, known as Dari.[71][73] The region, which comprised the present territories of northwestern Afghanistan as well as parts of Central Asia, played a leading role in the rise of New Persian. Khorasan, which was the homeland of the Parthians, was Persianized under the Sasanians. Dari Persian thus supplanted Parthian language (pahlavānīg), which by the end of the Sasanian era had fallen out of use.[71] New Persian has incorporated many foreign words, including from eastern northern and northern Iranian languages such as Sogdian and especially Parthian.[74]

The transition to New Persian was already complete by the era of the three princely dynasties of Iranian origin, the Tahirid dynasty (820–872), Saffarid dynasty (860–903), and Samanid Empire (874–999).[75] Abbas of Merv is mentioned as being the earliest minstrel to chant verse in the New Persian tongue and after him the poems of Hanzala Badghisi were among the most famous between the Persian-speakers of the time.[76]

The first significant Persian poet was Rudaki. He flourished in the 10th century, when the Samanids were at the height of their power. His reputation as a court poet and as an accomplished musician and singer has survived, although little of his poetry has been preserved. Among his lost works are versified fables collected in the Kalila wa Dimna.[24]

The language spread geographically from the 11th century on and was the medium through which, among others, Central Asian Turks became familiar with Islam and urban culture. New Persian was widely used as a trans-regional lingua franca, a task aided due to its relatively simple morphology, and this situation persisted until at least the 19th century.[77] In the late Middle Ages, new Islamic literary languages were created on the Persian model: Ottoman Turkish, Chagatai Turkic, Dobhashi Bengali, and Urdu, which are regarded as "structural daughter languages" of Persian.[77]

Classical Persian

[edit]

"Classical Persian" loosely refers to the standardized language of medieval Persia used in literature and poetry. This is the language of the 10th to 12th centuries, which continued to be used as literary language and lingua franca under the "Persianized" Turko-Mongol dynasties during the 12th to 15th centuries, and under restored Persian rule during the 16th to 19th centuries.[78]

Persian during this time served as lingua franca of Greater Persia and of much of the Indian subcontinent. It was also the official and cultural language of many Islamic dynasties, including the Samanids, Buyids, Tahirids, Ziyarids, the Mughal Empire, Timurids, Ghaznavids, Karakhanids, Seljuqs, Khwarazmians, the Sultanate of Rum, Turkmen beyliks of Anatolia, Delhi Sultanate, the Shirvanshahs, Safavids, Afsharids, Zands, Qajars, Khanate of Bukhara, Khanate of Kokand, Emirate of Bukhara, Khanate of Khiva, Ottomans, and also many Mughal successors such as the Nizam of Hyderabad. Persian was the only non-European language known and used by Marco Polo at the Court of Kublai Khan and in his journeys through China.[79][80]

Use in Asia Minor

[edit]

A branch of the Seljuks, the Sultanate of Rum, took Persian language, art, and letters to Anatolia.[81] They adopted the Persian language as the official language of the empire.[82] The Ottomans, who can roughly be seen as their eventual successors, inherited this tradition. Persian was the official court language of the empire, and for some time, the official language of the empire.[83] The educated and noble class of the Ottoman Empire all spoke Persian, such as Sultan Selim I, despite being Safavid Iran's archrival and a staunch opposer of Shia Islam.[84] It was a major literary language in the empire.[85] Some of the noted earlier Persian works during the Ottoman rule are Idris Bidlisi's Hasht Bihisht, which began in 1502 and covered the reign of the first eight Ottoman rulers, and the Salim-Namah, a glorification of Selim I.[84] After a period of several centuries, Ottoman Turkish (which was highly Persianised itself) had developed toward a fully accepted language of literature, and which was even able to lexically satisfy the demands of a scientific presentation.[86] However, the number of Persian and Arabic loanwords contained in those works increased at times up to 88%.[86] In the Ottoman Empire, Persian was used at the royal court, for diplomacy, poetry, historiographical works, literary works, and was taught in state schools, and was also offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas.[87]

Use in the Balkans

[edit]Persian learning was also widespread in the Ottoman-held Balkans (Rumelia), with a range of cities being famed for their long-standing traditions in the study of Persian and its classics, amongst them Saraybosna (modern Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina), Mostar (also in Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Vardar Yenicesi (or Yenice-i Vardar, now Giannitsa, in northern Greece).[88]

Vardar Yenicesi differed from other localities in the Balkans insofar as that it was a town where Persian was also widely spoken.[89] However, the Persian of Vardar Yenicesi and of the rest of the Ottoman-held Balkans was different from formal Persian both in accent and vocabulary.[89] The difference was apparent to such a degree that the Ottomans referred to it as "Rumelian Persian" (Rumili Farsisi).[89] As learned people such as students, scholars and literati often frequented Vardar Yenicesi, it soon became the site of a flourishing Persianate linguistic and literary culture.[89] The 16th-century Ottoman Aşık Çelebi (died 1572), who hailed from Prizren in modern-day Kosovo, was galvanized by the abundant Persian-speaking and Persian-writing communities of Vardar Yenicesi, and he referred to the city as a "hotbed of Persian".[89]

Many Ottoman Persianists who established a career in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) pursued early Persian training in Saraybosna, amongst them Ahmed Sudi.[90]

Use in Indian subcontinent

[edit]

The Persian language influenced the formation of many modern languages in West Asia, Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia. Following the Turko-Persian Ghaznavid conquest of South Asia, Persian was firstly introduced in the region by Turkic Central Asians.[91] The basis in general for the introduction of Persian language into the subcontinent was set, from its earliest days, by various Persianized Central Asian Turkic and Afghan dynasties.[81] For five centuries prior to the British colonization, Persian was widely used as a second language in the Indian subcontinent. It took prominence as the language of culture and education in several Muslim courts on the subcontinent and became the sole "official language" under the Mughal emperors.

The Bengal Sultanate witnessed an influx of Persian scholars, lawyers, teachers, and clerics. Thousands of Persian books and manuscripts were published in Bengal. The period of the reign of Sultan Ghiyathuddin Azam Shah is described as the "golden age of Persian literature in Bengal". Its stature was illustrated by the Sultan's own correspondence and collaboration with the Persian poet Hafez; a poem which can be found in the Divan of Hafez today.[92] A Bengali dialect emerged among the common Bengali Muslim folk, based on a Persian model and known as Dobhashi; meaning mixed language. Dobhashi Bengali was patronised and given official status under the Sultans of Bengal, and was a popular literary form used by Bengalis during the pre-colonial period, irrespective of their religion.[93]

Following the defeat of the Hindu Shahi dynasty, classical Persian was established as a courtly language in the region during the late 10th century under Ghaznavid rule over the northwestern frontier of the subcontinent.[94] Employed by Punjabis in literature, Persian achieved prominence in the region during the following centuries.[94] Persian continued to act as a courtly language for various empires in Punjab through the early 19th century serving finally as the official state language of the Sikh Empire, preceding British conquest and the decline of Persian in South Asia.[95][96][97]

Beginning in 1843, though, English and Hindustani gradually replaced Persian in importance on the subcontinent.[98] Evidence of Persian's historical influence there can be seen in the extent of its influence on certain languages of the Indian subcontinent. Words borrowed from Persian are still quite commonly used in certain Indo-Aryan languages, especially Hindi-Urdu (also historically known as Hindustani), Punjabi, Kashmiri, and Sindhi.[99] There is also a small population of Zoroastrian Iranis in India, who migrated in the 19th century to escape religious persecution in Qajar Iran and speak a Dari dialect.

Contemporary Persian

[edit]Qajar dynasty

[edit]

In the 19th century, under the Qajar dynasty, the dialect that is spoken in Tehran rose to prominence. There was still substantial Arabic vocabulary, but many of these words have been integrated into Persian phonology and grammar. In addition, under the Qajar rule, numerous Russian, French, and English terms entered the Persian language, especially vocabulary related to technology.

The first official attentions to the necessity of protecting the Persian language against foreign words, and to the standardization of Persian orthography, were under the reign of Naser ed Din Shah of the Qajar dynasty in 1871.[citation needed] After Naser ed Din Shah, Mozaffar ed Din Shah ordered the establishment of the first Persian association in 1903.[39] This association officially declared that it used Persian and Arabic as acceptable sources for coining words. The ultimate goal was to prevent books from being printed with wrong use of words. According to the executive guarantee of this association, the government was responsible for wrongfully printed books. Words coined by this association, such as rāh-āhan (راهآهن) for "railway", were printed in Soltani Newspaper; but the association was eventually closed due to inattention.[citation needed]

A scientific association was founded in 1911, resulting in a dictionary called Words of Scientific Association (لغت انجمن علمی), which was completed later and renamed Katouzian Dictionary (فرهنگ کاتوزیان).[100]

Pahlavi dynasty

[edit]The first academy for the Persian language was founded on 20 May 1935, under the name Academy of Iran. It was established by the initiative of Reza Shah Pahlavi, and mainly by Hekmat e Shirazi and Mohammad Ali Foroughi, all prominent names in the nationalist movement of the time. The academy was a key institution in the struggle to re-build Iran as a nation-state after the collapse of the Qajar dynasty. During the 1930s and 1940s, the academy led massive campaigns to replace the many Arabic, Russian, French, and Greek loanwords whose widespread use in Persian during the centuries preceding the foundation of the Pahlavi dynasty had created a literary language considerably different from the spoken Persian of the time. This became the basis of what is now known as "Contemporary Standard Persian".

Varieties

[edit]There are three standard varieties of modern Persian:

- Iranian Persian (Persian, Western Persian, or Farsi) is spoken in Iran, and by minorities in Iraq and the Persian Gulf states.

- Eastern Persian (Dari Persian, Afghan Persian, or Dari) is spoken in Afghanistan.

- Tajiki (Tajik Persian) is spoken in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It is written in the Cyrillic script.

All three varieties are based on the classic Persian literature and its literary tradition. There are also several local dialects from Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan which slightly differ from the standard Persian. The Hazaragi dialect (in Central Afghanistan and Pakistan), Herati (in Western Afghanistan), Darwazi (in Afghanistan and Tajikistan), Basseri (in Southern Iran), and the Tehrani accent (in Iran, the basis of standard Iranian Persian) are examples of these dialects. Persian-speaking peoples of Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan can understand one another with a relatively high degree of mutual intelligibility.[101] Nevertheless, the Encyclopædia Iranica notes that the Iranian, Afghan, and Tajiki varieties comprise distinct branches of the Persian language, and within each branch a wide variety of local dialects exist.[102]

The following are some languages closely related to Persian, or in some cases are considered dialects:

- Luri (or Lori), spoken mainly in the southwestern Iranian provinces of Lorestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari some western parts of Fars province, and some parts of Khuzestan province.

- Achomi (or Lari), spoken mainly in southern Iranian provinces of Fars and Hormozgan, unlike New Persian and its variants like Dari, Standard Persian, and Iranian Persian, this is a branch of Middle Persian.[103][104][105]

- Tat, spoken in parts of Azerbaijan, Russia, and Transcaucasia. It is classified as a variety of Persian.[106][107][108][109][110] (This dialect is not to be confused with the Tati language of northwestern Iran, which is a member of a different branch of the Iranian languages.)

- Judeo-Tat. Part of the Tat-Persian continuum, spoken in Azerbaijan, Russia, as well as by immigrant communities in Israel and New York.

More distantly related branches of the Iranian language family include Kurdish and Balochi.

The Glottolog database proposes the following phylogenetic classification:

- Farsic–Caucasian Tat

- Caucasian Tat

- Judeo-Tat

- Muslim Tat (including Armeno-Tat)

- Farsic

- Eastern Farsic

- Judeo-Persian

- Western Farsi

- Caucasian Tat

Phonology

[edit]Iranian Persian and Tajik have six vowels; Dari has eight. Iranian Persian has twenty-three consonants, but both Dari and Tajiki have twenty-four consonants, due to the phonemic merger of /q/ and /ɣ/ in Iranian Persian.[111]

Vowels

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Historically, Persian distinguished length. Early New Persian had a series of five long vowels (/iː/, /uː/, /ɑː/, /oː/, and /eː/) along with three short vowels /æ/, /i/, and /u/. At some point prior to the 16th century in the general area now modern Iran, /eː/ and /iː/ merged into /iː/, and /oː/ and /uː/ merged into /uː/. Thus, older contrasts such as شیر shēr "lion" vs. شیر shīr "milk", and زود zūd "quick" vs زور zōr "strength" were lost. However, there are exceptions to this rule, and in some words, ē and ō are merged into the diphthongs [eɪ] and [oʊ] (which are descendants of the diphthongs [æɪ] and [æʊ] in Early New Persian), instead of merging into /iː/ and /uː/. Examples of the exception can be found in words such as روشن [roʊʃæn] (bright). Numerous other instances exist.

However, in Dari, the archaic distinction of /eː/ and /iː/ (respectively known as یای مجهول Yā-ye majhūl and یای معروف Yā-ye ma'rūf) is still preserved as well as the distinction of /oː/ and /uː/ (known as واو مجهول Wāw-e majhūl and واو معروف Wāw-e ma'rūf). On the other hand, in standard Tajik, the length distinction has disappeared, and /iː/ merged with /i/ and /uː/ with /u/.[112] Therefore, contemporary Afghan Dari dialects are the closest to the vowel inventory of Early New Persian.[113]

According to most studies on the subject, the three vowels traditionally considered long (/i/, /u/, /ɒ/) are currently distinguished from their short counterparts (/e/, /o/, /æ/) by position of articulation rather than by length. However, there are studies that consider vowel length to be the active feature of the system, with /ɒ/, /i/, and /u/ phonologically long or bimoraic and /æ/, /e/, and /o/ phonologically short or monomoraic.[114]

There are also some studies that consider quality and quantity to be both active in the Iranian system. That offers a synthetic analysis including both quality and quantity, which often suggests that Modern Persian vowels are in a transition state between the quantitative system of Classical Persian and a hypothetical future Iranian language, which will eliminate all traces of quantity and retain quality as the only active feature. The length distinction is still strictly observed by careful reciters of classic-style poetry.[114]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Stop | p b | t d | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | k ɡ | (q) | ʔ |

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ɣ | h | |

| Tap | ɾ | |||||

| Approximant | l | j |

Notes:

- in Iranian Persian /ɣ/ and /q/ have merged into [ɣ~ɢ], as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ] when positioned intervocalically and unstressed, and as a voiced uvular stop [ɢ] otherwise.[115][116][117]

- /n/ is realized as [ŋ] before velar consonants.[citation needed]

Grammar

[edit]Morphology

[edit]Suffixes predominate Persian morphology, though there are a small number of prefixes.[118] Verbs can express tense and aspect, and they agree with the subject in person and number.[119] There is no grammatical gender in modern Persian, and pronouns are not marked for natural gender. In other words, in Persian, pronouns are gender-neutral. When referring to a masculine or a feminine subject, the same pronoun او is used (pronounced "ou", ū).[120]

Syntax

[edit]Persian adheres mainly to subject–object–verb (SOV) word order. But case endings (e.g. for subject, object, etc.) expressed via suffixes may allow users to vary word order. Verbs agree with the subject in person and number. Normal declarative sentences are structured as (S) (PP) (O) V: sentences have optional subjects, prepositional phrases, and objects followed by a compulsory verb. If the object is specific, the object is followed by the word rā and precedes prepositional phrases: (S) (O + rā) (PP) V.[119]

Vocabulary

[edit]Native word formation

[edit]Persian makes extensive use of word building and combining affixes, stems, nouns, and adjectives. Persian frequently uses derivational agglutination to form new words from nouns, adjectives, and verbal stems. New words are extensively formed by compounding – two existing words combining into a new one.

Influences

[edit]While having a lesser influence from Arabic[29] and other languages of Mesopotamia and its core vocabulary being of Middle Persian origin,[23] New Persian contains a considerable number of Arabic lexical items,[20][28][30] which were Persianized[31] and often took a different meaning and usage than the Arabic original. Persian loanwords of Arabic origin especially include Islamic terms. The Arabic vocabulary in other Iranian, Turkic, and Indic languages is generally understood to have been copied from New Persian, not from Arabic itself.[121]

John R. Perry, in his article "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic", estimates that about 20 percent of everyday vocabulary in current Persian, and around 25 percent of the vocabulary of classical and modern Persian literature, are of Arabic origin. The text frequency of these loan words is generally lower and varies by style and topic area. It may approach 25 percent of a text in literature.[122] According to another source, about 40% of everyday Persian literary vocabulary is of Arabic origin.[123] Among the Arabic loan words, relatively few (14 percent) are from the semantic domain of material culture, while a larger number are from domains of intellectual and spiritual life.[124] Most of the Arabic words used in Persian are either synonyms of native terms or could be glossed in Persian.[124]

The inclusion of Mongolic and Turkic elements in the Persian language should also be mentioned,[125] not only because of the political role a succession of Turkic dynasties played in Iranian history, but also because of the immense prestige Persian language and literature enjoyed in the wider (non-Arab) Islamic world, which was often ruled by sultans and emirs with a Turkic background. The Turkish and Mongolian vocabulary in Persian is minor in comparison to that of Arabic and these words were mainly confined to military, pastoral terms and political sector (titles, administration, etc.).[126] New military and political titles were coined based partially on Middle Persian (e.g. ارتش arteš for "army", instead of the Uzbek قؤشین qoʻshin; سرلشکر sarlaškar; دریابان daryābān; etc.) in the 20th century. Persian has likewise influenced the vocabularies of other languages, especially other Indo-European languages such as Armenian,[127] Urdu, Bengali, and Hindi; the latter three through conquests of Persianized Central Asian Turkic and Afghan invaders;[128] Turkic languages such as Ottoman Turkish, Chagatai, Tatar, Turkish,[129] Turkmen, Azeri,[130] Uzbek, and Karachay-Balkar;[131] Caucasian languages such as Georgian,[132] and, to a lesser extent, Avar and Lezgin;[133] Afro-Asiatic languages like Assyrian (List of loanwords in Assyrian Neo-Aramaic) and Arabic, particularly Bahrani Arabic;[27][134] and even Dravidian languages indirectly especially Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, and Brahui; as well as Austronesian languages such as Indonesian and Malaysian Malay. Persian has also had a significant lexical influence, via Turkish, on Albanian and Serbo-Croatian, particularly as spoken in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Use of occasional foreign synonyms instead of Persian words can be a common practice in everyday communications as an alternative expression. In some instances in addition to the Persian vocabulary, the equivalent synonyms from multiple foreign languages can be used. For example, in Iranian colloquial Persian (not in Afghanistan or Tajikistan), the phrase "thank you" may be expressed using the French word مرسی merci (stressed, however, on the first syllable), the hybrid Persian-Arabic phrase متشکّرَم motešakkeram (متشکّر motešakker being "thankful" in Arabic, commonly pronounced moččakker in Persian, and the verb ـَم am meaning "I am" in Persian), or by the pure Persian phrase سپاسگزارم sepās-gozāram.

Orthography

[edit]

The vast majority of modern Iranian Persian and Dari text is written with the Arabic script. Tajiki, which is considered by some linguists to be a Persian dialect influenced by Russian and the Turkic languages of Central Asia,[112][136] is written with the Cyrillic script in Tajikistan (see Tajik alphabet). There also exist several romanization systems for Persian.

Persian alphabet

[edit]Modern Iranian Persian and Afghan Persian are written using the Persian alphabet, which is a modified variant of the Arabic alphabet, using different pronunciation and additional letters not found in the Arabic language. After the Arab conquest of Persia, it took approximately 200 years before Persians adopted the Arabic script in place of the older alphabet. Previously, two different scripts were used, Pahlavi, used for Middle Persian, and the Avestan alphabet (in Persian, Dīndapirak, or Din Dabire—literally: religion script), used for religious purposes, primarily for the Avestan but sometimes for Middle Persian.

In the modern Persian script, historically short vowels are usually not written, only the historically long ones are represented in the text, so words distinguished from each other only by short vowels are ambiguous in writing: Iranian Persian kerm "worm", karam "generosity", kerem "cream", and krom "chrome" are all spelled krm (کرم) in Persian. The reader must determine the word from context. The Arabic system of vocalization marks known as harakat is also used in Persian, although some of the symbols have different pronunciations. For example, a ḍammah is pronounced [ʊ~u], while in Iranian Persian it is pronounced [o]. This system is not used in mainstream Persian literature; it is primarily used for teaching and in some (but not all) dictionaries.

There are several letters generally only used in Arabic loanwords. These letters are pronounced the same as similar Persian letters. For example, there are four functionally identical letters for /z/ (ز ذ ض ظ), three letters for /s/ (س ص ث), two letters for /t/ (ط ت), two letters for /h/ (ح ه). On the other hand, there are four letters that do not exist in Arabic پ چ ژ گ.

Additions

[edit]The Persian alphabet adds four letters to the Arabic alphabet:

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | پ | ـپ | ـپـ | پـ | pe |

| /tʃ/ | چ | ـچ | ـچـ | چـ | če (che) |

| /ʒ/ | ژ | ـژ | ـژ | ژ | že (zhe or jhe) |

| /ɡ/ | گ | ـگ | ـگـ | گـ | ge (gāf) |

Historically, there was also a special letter for the sound /β/. This letter is no longer used, as the /β/-sound changed to /b/, e.g. archaic زڤان /zaβaːn/ > زبان /zæbɒn/ 'language'[137]

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /β/ | ڤ | ـڤ | ـڤـ | ڤـ | βe |

Variations

[edit]The Persian alphabet also modifies some letters of the Arabic alphabet. For example, alef with hamza below ( إ ) changes to alef ( ا ); words using various hamzas get spelled with yet another kind of hamza (so that مسؤول becomes مسئول) even though the latter has been accepted in Arabic since the 1980s; and teh marbuta ( ة ) changes to heh ( ه ) or teh ( ت ).

The letters different in shape are:

| Arabic style letter | Persian style letter | Name |

|---|---|---|

| ك | ک | ke (kāf) |

| ي | ی | ye |

However, ی in shape and form is the traditional Arabic style that continues in the Nile Valley, namely, Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan.

Latin alphabet

[edit]The International Organization for Standardization has published a standard for simplified transliteration of Persian into Latin, ISO 233-3, titled "Information and documentation – Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters – Part 3: Persian language – Simplified transliteration"[138] but the transliteration scheme is not in widespread use.

Another Latin alphabet, based on the New Turkic Alphabet, was used in Tajikistan in the 1920s and 1930s. The alphabet was phased out in favor of Cyrillic in the late 1930s.[112]

Fingilish is Persian using ISO basic Latin alphabet. It is most commonly used in chat, emails, and SMS applications. The orthography is not standardized, and varies among writers and even media (for example, typing 'aa' for the [ɒ] phoneme is easier on computer keyboards than on cellphone keyboards, resulting in smaller usage of the combination on cellphones).

Tajik alphabet

[edit]The Cyrillic script was introduced for writing the Tajik language under the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic in the late 1930s, replacing the Latin alphabet that had been used since the October Revolution and the Persian script that had been used earlier. After 1939, materials published in Persian in the Persian script were banned in the country.[112][139]

Examples

[edit]The following text is from Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

| Iranian Persian (Nastaʿlīq) | همهی افراد بشر آزاد به دنیا میآیند و حیثیت و حقوقشان با هم برابر است، همه اندیشه و وجدان دارند و باید در برابر یکدیگر با روح برادری رفتار کنند. |

|---|---|

| Iranian Persian (Naskh) | همهی افراد بشر آزاد به دنیا میآیند و حیثیت و حقوقشان با هم برابر است، همه اندیشه و وجدان دارند و باید در برابر یکدیگر با روح برادری رفتار کنند. |

| Iranian Persian transliteration |

Hame-ye afrād-e bashar āzād be donyā mi āyand o heysiyat o hoquq-e shān bā ham barābar ast, hame andishe o vejdān dārand o bāyad dar barābare yekdigar bā ruh-e barādari raftār konand. |

| Iranian Persian IPA | [hæmeje æfrɒde bæʃær ɒzɒd be donjɒ miɒjænd o hejsijæt o hoɢuɢe ʃɒn bɒ hæm bærɒbær æst hæme ʃɒn ændiʃe o vedʒdɒn dɒrænd o bɒjæd dær bærɒbære jekdiɡær bɒ ruhe bærɒdæri ræftɒr konænd] |

| Tajiki | Ҳамаи афроди башар озод ба дунё меоянд ва ҳайсияту ҳуқуқашон бо ҳам баробар аст, ҳамаашон андешаву виҷдон доранд ва бояд дар баробари якдигар бо рӯҳи бародарӣ рафтор кунанд. |

| Tajiki transliteration |

Hamai afrodi bashar ozod ba dunjo meoyand va haysiyatu huquqashon bo ham barobar ast, hamaashon andeshavu vijdon dorand va boyad dar barobari yakdigar bo rūhi barodarī raftor kunand. |

| English translation | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

See also

[edit]- Academy of Persian Language and Literature

- Indo-European copula

- Iranian languages

- Iranian Persian, Western Persian

- List of countries and territories where Persian is an official language

- List of English words of Persian origin

- List of French loanwords in Persian

- Middle Persian

- Parthian language

- Persian Braille

- Persian metres

- Persian name

- Romanization of Persian

- List of link languages

- Dialect continuum

- Geolinguistics

- Language geography

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Samadi, Habibeh; Nick Perkins (2012). Martin Ball; David Crystal; Paul Fletcher (eds.). Assessing Grammar: The Languages of Lars. Multilingual Matters. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-84769-637-3.

- ^ a b Foltz, Richard (1996). "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan". Central Asian Survey. 15 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1080/02634939608400946. ISSN 0263-4937.

- ^ "IRAQ". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union. London: Routledge. p. 362. ISBN 0-7103-0188-X.

- ^ a b Windfuhr, Gernot: The Iranian Languages, Routledge 2009, p. 417–418.

- ^ "Kuwaiti Persian". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "What Languages Are Spoken in Bahrain?". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ a b c Persian language at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ a b c Windfuhr, Gernot: The Iranian Languages, Routledge 2009, p. 418.

- ^ a b Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran: Chapter II, Article 15: "The official language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as text-books, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian."

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Dagestan: Chapter I, Article 11: "The state languages of the Republic of Dagestan are Russian and the languages of the peoples of Dagestan."

- ^ "Persian, Iranian". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "639 Identifier Documentation: fas". Sil.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran". Islamic Parliament of Iran. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ a b Olesen, Asta (1995). Islam and Politics in Afghanistan. Vol. 3. Psychology Press. p. 205.

There began a general promotion of the Pashto language at the expense of Farsi – previously dominant in the educational and administrative system (...) – and the term 'Dari' for the Afghan version of Farsi came into common use, being officially adopted in 1958.

- ^ Siddikzoda, S. "Tajik Language: Farsi or not Farsi?" in Media Insight Central Asia #27, August 2002.

- ^ a b Baker, Mona (2001). Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. Psychology Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-415-25517-2. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

All this affected translation activities in Persian, seriously undermining the international character of the language. The problem was compounded in modern times by several factors, among them the realignment of Central Asian Persian, renamed Tajiki by the Soviet Union, with Uzbek and Russian languages, as well as the emergence of a language reform movement in Iran which paid no attention to the consequences of its pronouncements and actions for the language as a whole.

- ^ Jonson, Lena (2006). Tajikistan in the new Central Asia. p. 108.

- ^ Cordell, Karl (1998). Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 0415173124.

Consequently the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajiks within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academics and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30 per cent of the republic's twenty-two million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7 per cent (Foltz 1996:213; Carlisle 1995:88).

- ^ a b c d e Lazard 1975: "The language known as New Persian, which usually is called at this period (early Islamic times) by the name of Dari or Farsi-Dari, can be classified linguistically as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of Sassanian Iran, itself a continuation of Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenids. Unlike the other languages and dialects, ancient and modern, of the Iranian group such as Avestan, Parthian, Soghdian, Kurdish, Balochi, Pashto, etc., Old Persian, Middle Persian, and New Persian represent one and the same language at three states of its history. It had its origin in Fars (the true Persian country from the historical point of view) and is differentiated by dialectical features, still easily recognizable from the dialect prevailing in north-western and eastern Iran."

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (2006). Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 1912.

The Pahlavi language (also known as Middle Persian) was the official language of Iran during the Sassanid dynasty (from 3rd to 7th century A. D.). Pahlavi is the direct continuation of old Persian, and was used as the written official language of the country. However, after the Moslem conquest and the collapse of the Sassanids, Arabic became the dominant language of the country and Pahlavi lost its importance, and was gradually replaced by Dari, a variety of Middle Persian, with considerable loan elements from Arabic and Parthian (Moshref 2001).

- ^ Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2006). "Iran, vi. Iranian languages and scripts". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. pp. 344–377. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

(...) Persian, the language originally spoken in the province of Fārs, which is descended from Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenid empire (6th–4th centuries B.C.E.), and Middle Persian, the language of the Sasanian empire (3rd–7th centuries C.E.).

- ^ a b c Davis, Richard (2006). "Persian". In Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jere L. (eds.). Medieval Islamic Civilization. Taylor & Francis. pp. 602–603.

Similarly, the core vocabulary of Persian continued to be derived from Pahlavi, but Arabic lexical items predominated for more abstract or abstruse subjects and often replaced their Persian equivalents in polite discourse. (...) The grammar of New Persian is similar to that of many contemporary European languages.

- ^ a b c de Bruijn, J.T.P. (14 December 2015). "Persian literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Skjærvø, Prods Oktor. "Iran vi. Iranian languages and scripts (2) Documentation". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. pp. 348–366. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Egger, Vernon O. (16 September 2016). A History of the Muslim World since 1260: The Making of a Global Community. Routledge. ISBN 9781315511078. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ a b Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. BRILL. p. XXX. ISBN 90-04-10763-0. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ a b Lazard, Gilbert (1971). "Pahlavi, Pârsi, dari: Les langues d'Iran d'apès Ibn al-Muqaffa". In Frye, R.N. (ed.). Iran and Islam. In Memory of the late Vladimir Minorsky. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ a b Namazi, Nushin (24 November 2008). "Persian Loan Words in Arabic". Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ a b Classe, Olive (2000). Encyclopedia of literary translation into English. Taylor & Francis. p. 1057. ISBN 1-884964-36-2. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

Since the Arab conquest of the country in 7th century AD, many loan words have entered the language (which from this time has been written with a slightly modified version of the Arabic script) and the literature has been heavily influenced by the conventions of Arabic literature.

- ^ a b Lambton, Ann K. S. (1953). Persian grammar. Cambridge University Press.

The Arabic words incorporated into the Persian language have become Persianized.

- ^ Vafa, A; Abedinifard, M; Azadibougar, O (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. US: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 2–14. ISBN 978-1-501-35420-5.

- ^ Perry 2005, p. 284.

- ^ Green, Nile (2012). Making Space: Sufis and Settlers in Early Modern India. Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9780199088751. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Windfuhr, Gernot (1987). Comrie, Berard (ed.). The World's Major Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 523–546. ISBN 978-0-19-506511-4.

- ^ Περσίς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Persia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary online, s.v. "Persian", draft revision June 2007.

- ^ a b Jazayeri, M. A. (15 December 1999). "Farhangestān". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Zaban-i Nozohur". Iran-Shenasi: A Journal of Iranian Studies. IV (I): 27–30. 1992.

- ^ Spooner, Brian; Hanaway, William L. (2012). Literacy in the Persianate World: Writing and the Social Order. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 6, 81. ISBN 978-1934536568. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Spooner, Brian (2012). "Dari, Farsi, and Tojiki". In Schiffman, Harold (ed.). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. Leiden: Brill. p. 94. ISBN 978-9004201453. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Campbell, George L.; King, Gareth, eds. (2013). "Persian". Compendium of the World's Languages (3rd ed.). Routledge. p. 1339. ISBN 9781136258466. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Perry, John R. "Persian morphology." Morphologies of Asia and Africa 2 (2007): 975–1019.

- ^ Seraji, Mojgan, Beáta Megyesi, and Joakim Nivre. "A basic language resource kit for Persian." Eight International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2012), 23–25 May 2012, Istanbul, Turkey. European Language Resources Association, 2012.

- ^ Sahranavard, Neda, and Jerry Won Lee. "The Persianization of English in multilingual Tehran." World Englishes (2020).

- ^ Richardson, Charles Francis (1892). The International Cyclopedia: A Compendium of Human Knowledge. Dodd, Mead. p. 541.

- ^ Strazny, Philipp (2013). Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Routledge. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-135-45522-4.

- ^ Lazard, Gilbert (17 November 2011). "Darī". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VII. pp. 34–35. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

It is derived from the word for dar (court, lit., "gate"). Darī was thus the language of the court and of the capital, Ctesiphon. On the other hand, it is equally clear from this passage that darī was also in use in the eastern part of the empire, in Khorasan, where in the course of the Sasanian period Persian gradually supplanted Parthian and no dialect that was not Persian survived. The passage thus suggests that darī was actually a form of Persian, the common language of Persia. (...) Both were called pārsī (Persian), but it is very likely that the language of the north, that is, the Persian used on former Parthian territory and also in the Sasanian capital, was distinguished from its congener by a new name, darī ([language] of the court).

- ^ Paul, Ludwig (19 November 2013). "Persian Language: i: Early New Persian". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

Northeast. Khorasan, the homeland of the Parthians (called abaršahr "the upper lands" in MP), had been partly Persianized already in late Sasanian times. Following Ebn al-Moqaffaʿ, the variant of Persian spoken there was called Darī and was based upon the one used in the Sasanian capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon (Ar. al-Madāʾen). (...) Under the specific historical conditions that have been sketched above, the Dari (Middle) Persian of the 7th century was developed, within two centuries, to the Dari (New) Persian that is attested in the earliest specimens of NP poetry in the late 9th century.

- ^ Perry, John (20 July 2009). "Tajik ii. Tajik Persian". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "639 Identifier Documentation: fas". Sil.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "639 Identifier Documentation: tgk". Sil.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Skjærvø 2006 vi(2). Documentation.

- ^ a b cf. Skjærvø 2006 vi(2). Documentation. Excerpt 1: "Only the official languages Old, Middle, and New Persian represent three stages of one and the same language, whereas close genetic relationships are difficult to establish between other Middle and Modern Iranian languages. Modern Yaḡnōbi belongs to the same dialect group as Sogdian, but is not a direct descendant; Bactrian may be closely related to modern Yidḡa and Munji (Munjāni); and Wakhi (Wāḵi) belongs with Khotanese. Excerpt 2: New Persian, the descendant of Middle Persian and official language of Iranian states for centuries."

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (2003). The Major Languages of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-93257-3., p. 82. "The evolution of Persian as the culturally dominant language of major parts of the Near East, from Anatolia and Iran, to Central Asia, to northwest India until recent centuries, began with the political domination of these areas by dynasties originating in southwestern province of Iran, Pars, later Arabicised to Fars: first the Achaemenids (599–331 BC) whose official language was Old Persian; then the Sassanids (c. AD 225–651) whose official language was Middle Persian. Hence, the entire country used to be called Perse by the ancient Greeks, a practice continued to this day. The more general designation 'Iran(-shahr)" derives from Old Iranian aryanam (Khshathra)' (the realm) of Aryans'. The dominance of these two dynasties resulted in Old and Middle-Persian colonies throughout the empire, most importantly for the course of the development of Persian, in the north-east i.e., what is now Khorasan, northern Afghanistan, and Central Asia, as documented by the Middle Persian texts of the Manichean found in the oasis city of Turfan in Chinese Turkistan (Sinkiang). This led to certain degree of regionalisation".

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (1990) The major languages of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa, Taylor & Francis, p. 82

- ^ Barbara M. Horvath, Paul Vaughan, Community languages, 1991, p. 276

- ^ L. Paul (2005), "The Language of the Shahnameh in historical and dialectical perspective", p. 150: "The language of the Shahnameh should be seen as one instance of continuous historical development from Middle to New Persian.", in Weber, Dieter; MacKenzie, D. N. (2005). Languages of Iran: Past and Present: Iranian Studies in Memoriam David Neil MacKenzie. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05299-3. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Schmitt 2008, pp. 80–1.

- ^ Kuhrt 2013, p. 197.

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 103.

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 53.

- ^ "Roland G. Kent, Old Persian, 1953". Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 6. American Oriental Society, 1950.

- ^ a b c Skjærvø 2006, vi(2). Documentation. Old Persian.

- ^ a b Skjærvø 2006, vi(1). Earliest Evidence

- ^ Xenophon. Anabasis. pp. IV.v.2–9.

- ^ Nicholas Sims-Williams, "The Iranian Languages", in Steever, Sanford (ed.) (1993), The Indo-European Languages, p. 129.

- ^ Jeremias, Eva M. (2004). "Iran, iii. (f). New Persian". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 12 (New Edition, Supplement ed.). p. 432. ISBN 90-04-13974-5.

- ^ a b c Paul 2000.

- ^ Lazard 1975, p. 596.

- ^ Perry 2011.

- ^ Lazard 1975, p. 597.

- ^ Jackson, A. V. Williams. 1920. Early Persian poetry, from the beginnings down to the time of Firdausi. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp.17–19. (in Public Domain)

- ^ Jackson, A. V. Williams.pp.17–19.

- ^ a b Johanson, Lars, and Christiane Bulut. 2006. Turkic-Iranian contact areas: historical and linguistic aspects Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ^ according to iranchamber.com Archived 29 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine "the language (ninth to thirteenth centuries), preserved in the literature of the Empire, is known as Classical Persian, due to the eminence and distinction of poets such as Roudaki, Ferdowsi, and Khayyam. During this period, Persian was adopted as the lingua franca of the eastern Islamic nations. Extensive contact with Arabic led to a large influx of Arab vocabulary. In fact, a writer of Classical Persian had at one's disposal the entire Arabic lexicon and could use Arab terms freely either for literary effect or to display erudition. Classical Persian remained essentially unchanged until the nineteenth century, when the dialect of Teheran rose in prominence, having been chosen as the capital of Persia by the Qajar Dynasty in 1787. This Modern Persian dialect became the basis of what is now called Contemporary Standard Persian. Although it still contains a large number of Arab terms, most borrowings have been nativized, with a much lower percentage of Arabic words in colloquial forms of the language."

- ^ Yazıcı, Tahsin (2010). "Persian authors of Asia Minor part 1". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

Persian language and culture were actually so popular and dominant in this period that in the late 14th century, Moḥammad (Meḥmed) Bey, the founder and the governing head of the Qaramanids, published an official edict to end this supremacy, saying that: "The Turkish language should be spoken in courts, palaces, and at official institutions from now on!"

- ^ John Andrew Boyle, Some thoughts on the sources for the Il-Khanid period of Persian history, in Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies, British Institute of Persian Studies, vol. 12 (1974), p. 175.

- ^ a b de Laet, Sigfried J. (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2016., p 734

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Wastl-Walter, Doris (2011). The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-7546-7406-1. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b Spuler 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Lewis, Franklin D. (2014). Rumi – Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi. Oneworld Publications. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-78074-737-8. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b Spuler 2003, p. 69.

- ^

- Chapter "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian Learning in the Ottoman World" by Inan, Murat Umut. In Green, Nile (ed.), 2019, The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. pp. 88–89. "As the Ottoman Turks learned Persian, the language and the culture it carried seeped not only into their court and imperial institutions but also into their vernacular language and culture. The appropriation of Persian, both as a second language and as a language to be steeped together with Turkish, was encouraged notably by the sultans, the ruling class, and leading members of the mystical communities."

- Chapter "Ottoman Historical Writing" by Tezcan, Baki. In Rabasa, José (ed.), 2012, The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800 The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–211. "Persian served as a 'minority' prestige language of culture at the largely Turcophone Ottoman court."

- Learning to Read in the Late Ottoman Empire and the Early Turkish Republic, B. Fortna, page 50;"Although in the late Ottoman period Persian was taught in the state schools...."

- Persian Historiography and Geography, Bertold Spuler, page 68, "On the whole, the circumstance in Turkey took a similar course: in Anatolia, the Persian language had played a significant role as the carrier of civilization.[..]..where it was at time, to some extent, the language of diplomacy...However Persian maintained its position also during the early Ottoman period in the composition of histories and even Sultan Salim I, a bitter enemy of Iran and the Shi'ites, wrote poetry in Persian. Besides some poetical adaptations, the most important historiographical works are: Idris Bidlisi's flowery "Hasht Bihist", or Seven Paradises, begun in 1502 by the request of Sultan Bayazid II and covering the first eight Ottoman rulers.."

- Picturing History at the Ottoman Court, Emine Fetvacı, page 31, "Persian literature, and belles-lettres in particular, were part of the curriculum: a Persian dictionary, a manual on prose composition; and Sa'dis "Gulistan", one of the classics of Persian poetry, were borrowed. All these title would be appropriate in the religious and cultural education of the newly converted young men.

- Persian Historiography: History of Persian Literature A, Volume 10, edited by Ehsan Yarshater, Charles Melville, page 437;"...Persian held a privileged place in Ottoman letters. Persian historical literature was first patronized during the reign of Mehmed II and continued unabated until the end of the 16th century.

- Chapter Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World, Murat Umut Inan, page 92 (note 27), edited by Nile Green, (title: The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca); "Though Persian, unlike Arabic, was not included in the typical curriculum of an Ottoman madrasa, the language was offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas. For those Ottoman madrasa curricula featuring Persian, see Cevat İzgi, Osmanlı Medreselerinde İlim, 2 vols. (Istanbul: İz, 1997),1: 167–69."

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c d e Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. p. 86.

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. p. 85.

- ^ Bennett, Clinton; Ramsey, Charles M. (2012). South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny. A&C Black. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4411-5127-8. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Abu Musa Mohammad Arif Billah (2012). "Persian". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ Sarah Anjum Bari (12 April 2019). "A Tale of Two Languages: How the Persian language seeped into Bengali". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ a b Mir, F. (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780520262690. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 892.

- ^ Grewal, J. S. (1990). The Sikhs of the Punjab, Chapter 6: The Sikh empire (1799–1849). The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-521-63764-3. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

The continuance of Persian as the language of administration.

- ^ Fenech, Louis E. (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press (USA). p. 239. ISBN 978-0199931453. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

We see such acquaintance clearly within the Sikh court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, for example, the principal language of which was Persian.

- ^ Clawson, Patrick (2004). Eternal Iran. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6.

- ^ Menon, A.S.; Kusuman, K.K. (1990). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. p. 87. ISBN 9788170992141. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ نگار داوری اردکانی (1389). برنامهریزی زبان فارسی. روایت فتح. p. 33. ISBN 978-600-6128-05-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Beeman, William. "Persian, Dari and Tajik" (PDF). Brown University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ Aliev, Bahriddin; Okawa, Aya (2010). "TAJIK iii. COLLOQUIAL TAJIKI IN COMPARISON WITH PERSIAN OF IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Talei, Maryam; Rovshan, Belghis (24 October 2024). "Semantic Network in Lari Language". Persian Language and Iranian Dialects. 9 (1): 31–61. doi:10.22124/plid.2024.27553.1673. ISSN 2476-6585. Archived from the original on 28 November 2024.

This descriptive-analytical research examines sense relations between the lexemes of the Lari language, the continuation of the Middle Persian and one of the endangered Iranian languages spoken in Lar, Fars province

- ^ "Western Iranian languages History". Destination Iran. 16 June 2024. Archived from the original on 28 November 2024. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

Achomi or Khodmooni (Larestani) is a southwestern Iranian language spoken in southern Fars province and the Ajam (non-arab) population in Persian Gulf countries such as UAE, Bahrain, and Kuwait. It is a descendant of Middle Persian and has several dialects including Lari, Evazi, Khoni, Bastaki, and more.

- ^ Taherkhani, Neda; Ourang, Muhammed (2013). "A Study of Derivational Morphemes in Lari & Tati as Two Endangered Iranian Languages: An Analytical Contrastive Examination with Persian" (PDF). Journal of American Science. ISSN 1545-1003.

Lari is of the SW branch of Middle Iranian languages, Pahlavi, in the Middle period of Persian Language Evolution and consists of nine dialects, which are prominently different in pronunciation (Geravand, 2010). Being a branch of Pahlavi language, Lari has several common features with it as its mother language. The ergative structure (the difference between the conjugation of transitive and intransitive verbs) existing in Lari can be mentioned as such an example. The speech community of this language includes Fars province, Hormozgan Province and some of the Arabic-speaking countries like the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman (Khonji, 2010, p. 15).

- ^ Windfuhr 1979, p. 4: "Tat-Persian spoken in the East Caucasus"

- ^ V. Minorsky, "Tat" in M. Th. Houtsma et al., eds., The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples, 4 vols. and Suppl., Leiden: Late E.J. Brill and London: Luzac, 1913–38.

- ^ V. Minorsky, "Tat" in M. Th. Houtsma et al., eds., The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples, 4 vols. and Suppl., Leiden: Late E.J. Brill and London: Luzac, 1913–38. Excerpt: "Like most Persian dialects, Tati is not very regular in its characteristic features"

- ^ C Kerslake, Journal of Islamic Studies (2010) 21 (1): 147–151. excerpt: "It is a comparison of the verbal systems of three varieties of Persian—standard Persian, Tat, and Tajik—in terms of the 'innovations' that the latter two have developed for expressing finer differentiations of tense, aspect, and modality..." [1] Archived 17 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Borjian, Habib (2006). "Tabari Language Materials from Il'ya Berezin's Recherches sur les dialectes persans". Iran & the Caucasus. 10 (2): 243–258. doi:10.1163/157338406780346005.

It embraces Gilani, Talysh, Tabari, Kurdish, Gabri, and the Tati Persian of the Caucasus, all but the last belonging to the north-western group of Iranian language.

- ^ Miller, Corey (January 2012). "Vowel system of Contemporary Iranian Persian". Variation in Persian Vowel Systems. Retrieved 7 May 2022 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c d Perry 2005.

- ^ Okati 2012, p. 93.

- ^ a b Okati 2012, p. 92.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0.

- ^ Jahani, Carina (2005). "The Glottal Plosive: A Phoneme in Spoken Modern Persian or Not?". In Éva Ágnes Csató; Bo Isaksson; Carina Jahani (eds.). Linguistic Convergence and Areal Diffusion: Case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 79–96. ISBN 0-415-30804-6.

- ^ Thackston, W. M. (1 May 1993). "The Phonology of Persian". An Introduction to Persian (3rd Rev ed.). Ibex Publishers. p. xvii. ISBN 0-936347-29-5.

- ^ Megerdoomian, Karine (2000). "Persian computational morphology: A unification-based approach" (PDF). Memoranda in Computer and Cognitive Science: MCCS-00-320. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ a b Mahootian, Shahrzad (1997). Persian. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02311-4. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Yousef, Saeed; Torabi, Hayedeh (2013). Basic Persian: A Grammar and Workbook. New York: Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 9781136283888. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ John R. Perry, "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic" in Éva Ágnes Csató, Eva Agnes Csato, Bo Isaksson, Carina Jahani, Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, 2005. pg 97: "It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranian, Turkic, and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries"

- ^ John R. Perry, "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic" in Éva Ágnes Csató, Eva Agnes Csato, Bo Isaksson, Carina Jahani, Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, 2005. p.97

- ^ Owens, Jonathan (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. OUP USA. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-19-976413-6.

- ^ a b Perry 2005, p. 99.

- ^ e.g. The role of Azeri–Turkish in Iranian Persian, on which see John Perry, "The Historical Role of Turkish in Relation to Persian of Iran", Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 5 (2001), pp. 193–200.

- ^ Xavier Planhol, "Land of Iran", Encyclopedia Iranica. "The Turks, on the other hand, posed a formidable threat: their penetration into Iranian lands was considerable, to such an extent that vast regions adapted their language. This process was all the more remarkable since, in spite of their almost uninterrupted political domination for nearly 1,500 years, the cultural influence of these rough nomads on Iran's refined civilization remained extremely tenuous. This is demonstrated by the mediocre linguistic contribution, for which exhaustive statistical studies have been made (Doerfer). The number of Turkish or Mongol words that entered Persian, though not negligible, remained limited to 2,135, i.e., 3 percent of the vocabulary at the most. These new words are confined on the one hand to the military and political sector (titles, administration, etc.) and, on the other hand, to technical pastoral terms. The contrast with Arab influence is striking. While cultural pressure of the Arabs on Iran had been intense, they in no way infringed upon the entire Iranian territory, whereas with the Turks, whose contributions to Iranian civilization were modest, vast regions of Iranian lands were assimilated, notwithstanding the fact that resistance by the latter was ultimately victorious. Several reasons may be offered."

- ^ "ARMENIA AND IRAN iv. Iranian influences in Armenian Language". Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Bennett, Clinton; Ramsey, Charles M. (March 2012). South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441151278. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Andreas Tietze, Persian loanwords in Anatolian Turkish, Oriens, 20 (1967) pp- 125–168. Archived 11 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (accessed August 2016)

- ^ L. Johanson, "Azerbaijan: Iranian Elements in Azeri Turkish" in Encyclopedia Iranica Iranica.com

- ^ George L. Campbell; Gareth King (2013). Compendium of the World Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-25846-6. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Georgia v. Linguistic Contacts With Iranian Languages". Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "DAGESTAN". Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ Pasad. "Bashgah.net". Bashgah.net. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Smith 1989.