Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Direct stiffness method

View on WikipediaIn structural engineering, the direct stiffness method, also known as the matrix stiffness method, is a structural analysis technique particularly suited for computer-automated analysis of complex structures including the statically indeterminate type. It is a matrix method that makes use of the members' stiffness relations for computing member forces and displacements in structures. The direct stiffness method is the most common implementation of the finite element method (FEM). In applying the method, the system must be modeled as a set of simpler, idealized elements interconnected at the nodes. The material stiffness properties of these elements are then, through linear algebra, compiled into a single matrix equation which governs the behaviour of the entire idealized structure. The structure’s unknown displacements and forces can then be determined by solving this equation. The direct stiffness method forms the basis for most finite element software.

The direct stiffness method originated in the field of aerospace. Researchers looked at various approaches for analysis of complex airplane frames. These included elasticity theory, energy principles in structural mechanics, flexibility method and matrix stiffness method. It was through analysis of these methods that the direct stiffness method emerged as an efficient method ideally suited for computer implementation.

History

[edit]Between 1934 and 1938 A. R. Collar and W. J. Duncan published the first papers with the representation and terminology for matrix systems that are used today. Aeroelastic research continued through World War II but publication restrictions from 1938 to 1947 make this work difficult to trace. The second major breakthrough in matrix structural analysis occurred through 1954 and 1955 when professor John H. Argyris systemized the concept of assembling elemental components of a structure into a system of equations. Finally, on Nov. 6 1959, M. J. Turner, head of Boeing’s Structural Dynamics Unit, published a paper outlining the direct stiffness method as an efficient model for computer implementation (Felippa 2001).

Member stiffness relations

[edit]A typical member stiffness relation has the following general form:

| 1 |

where

- m = member number m.

- = vector of member's characteristic forces, which are unknown internal forces.

- = member stiffness matrix which characterizes the member's resistance against deformations.

- = vector of member's characteristic displacements or deformations.

- = vector of member's characteristic forces caused by external effects (such as known forces and temperature changes) applied to the member while .

If are member deformations rather than absolute displacements, then are independent member forces, and in such case (1) can be inverted to yield the so-called member flexibility matrix, which is used in the flexibility method.

System stiffness relation

[edit]For a system with many members interconnected at points called nodes, the members' stiffness relations such as Eq.(1) can be integrated by making use of the following observations:

- The member deformations can be expressed in terms of system nodal displacements r in order to ensure compatibility between members. This implies that r will be the primary unknowns.

- The member forces help to the keep the nodes in equilibrium under the nodal forces R. This implies that the right-hand-side of (1) will be integrated into the right-hand-side of the following nodal equilibrium equations for the entire system:

| 2 |

where

- = vector of nodal forces, representing external forces applied to the system's nodes.

- = system stiffness matrix, which is established by assembling the members' stiffness matrices .

- = vector of system's nodal displacements that can define all possible deformed configurations of the system subject to arbitrary nodal forces R.

- = vector of equivalent nodal forces, representing all external effects other than the nodal forces which are already included in the preceding nodal force vector R. This vector is established by assembling the members' .

Solution

[edit]The system stiffness matrix K is square since the vectors R and r have the same size. In addition, it is symmetric because is symmetric. Once the supports' constraints are accounted for in (2), the nodal displacements are found by solving the system of linear equations (2), symbolically:

Subsequently, the members' characteristic forces may be found from Eq.(1) where can be found from r by compatibility consideration.

The direct stiffness method

[edit]It is common to have Eq.(1) in a form where and are, respectively, the member-end displacements and forces matching in direction with r and R. In such case, and can be obtained by direct summation of the members' matrices and . The method is then known as the direct stiffness method.

The advantages and disadvantages of the matrix stiffness method are compared and discussed in the flexibility method article.

Example

[edit]Breakdown

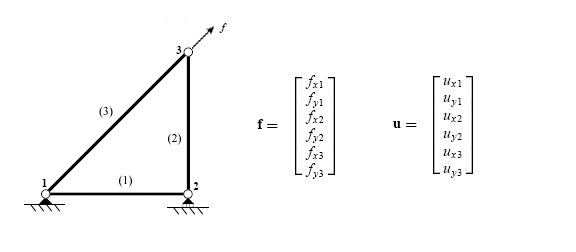

[edit]The first step when using the direct stiffness method is to identify the individual elements which make up the structure.

Once the elements are identified, the structure is disconnected at the nodes, the points which connect the different elements together.

Each element is then analyzed individually to develop member stiffness equations. The forces and displacements are related through the element stiffness matrix which depends on the geometry and properties of the element.

A truss element can only transmit forces in compression or tension. This means that in two dimensions, each node has two degrees of freedom (DOF): horizontal and vertical displacement. The resulting equation contains a four by four stiffness matrix.

A frame element is able to withstand bending moments in addition to compression and tension. This results in three degrees of freedom: horizontal displacement, vertical displacement and in-plane rotation. The stiffness matrix in this case is six by six.

Other elements such as plates and shells can also be incorporated into the direct stiffness method and similar equations must be developed.

Assembly

[edit]Once the individual element stiffness relations have been developed they must be assembled into the original structure. The first step in this process is to convert the stiffness relations for the individual elements into a global system for the entire structure. In the case of a truss element, the global form of the stiffness method depends on the angle of the element with respect to the global coordinate system (This system is usually the traditional Cartesian coordinate system).

(for a truss element at angle β) Equivalently,

where and are the direction cosines of the truss element (i.e., they are components of a unit vector aligned with the member). This form reveals how to generalize the element stiffness to 3-D space trusses by simply extending the pattern that is evident in this formulation.

After developing the element stiffness matrix in the global coordinate system, they must be merged into a single “master” or “global” stiffness matrix. When merging these matrices together there are two rules that must be followed: compatibility of displacements and force equilibrium at each node. These rules are upheld by relating the element nodal displacements to the global nodal displacements.

The global displacement and force vectors each contain one entry for each degree of freedom in the structure. The element stiffness matrices are merged by augmenting or expanding each matrix in conformation to the global displacement and load vectors.

(for element (1) of the above structure)

Finally, the global stiffness matrix is constructed by adding the individual expanded element matrices together.

Solution

[edit]Once the global stiffness matrix, displacement vector, and force vector have been constructed, the system can be expressed as a single matrix equation.

For each degree of freedom in the structure, either the displacement or the force is known.

After inserting the known value for each degree of freedom, the master stiffness equation is complete and ready to be evaluated. There are several different methods available for evaluating a matrix equation including but not limited to Cholesky decomposition and the brute force evaluation of systems of equations. If a structure isn’t properly restrained, the application of a force will cause it to move rigidly and additional support conditions must be added.

The method described in this section is meant as an overview of the direct stiffness method. Additional sources should be consulted for more details on the process as well as the assumptions about material properties inherent in the process.

Applications

[edit]The direct stiffness method was developed specifically to effectively and easily implement into computer software to evaluate complicated structures that contain a large number of elements. Today, nearly every finite element solver available is based on the direct stiffness method. While each program utilizes the same process, many have been streamlined to reduce computation time and reduce the required memory. In order to achieve this, shortcuts have been developed.

One of the largest areas to utilize the direct stiffness method is the field of structural analysis where this method has been incorporated into modeling software. The software allows users to model a structure and, after the user defines the material properties of the elements, the program automatically generates element and global stiffness relationships. When various loading conditions are applied the software evaluates the structure and generates the deflections for the user.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]References

[edit]- Felippa, Carlos A. (2001), "A historical outline of matrix structural analysis: a play in three acts" (PDF), Computers & Structures, 79 (14): 1313–1324, doi:10.1016/S0045-7949(01)00025-6, ISSN 0045-7949, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-29, retrieved 2005-10-05

- Felippa, Carlos A. Introduction to Finite Element Method. Fall 2001. University of Colorado. 18 Sept. 2005

- Robinson, John. Structural Matrix Analysis for the Engineer. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1966

- Rubinstein, Moshe F. Matrix Computer Analysis of Structures. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1966

- McGuire, W., Gallagher, R. H., and Ziemian, R. D. Matrix Structural Analysis, 2nd Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{bmatrix}f_{x1}\\f_{y1}\\\hline f_{x2}\\f_{y2}\end{bmatrix}}={\frac {EA}{L}}\left[{\begin{array}{c c|c c}c_{x}c_{x}&c_{x}c_{y}&-c_{x}c_{x}&-c_{x}c_{y}\\c_{y}c_{x}&c_{y}c_{y}&-c_{y}c_{x}&-c_{y}c_{y}\\\hline -c_{x}c_{x}&-c_{x}c_{y}&c_{x}c_{x}&c_{x}c_{y}\\-c_{y}c_{x}&-c_{y}c_{y}&c_{y}c_{x}&c_{y}c_{y}\\\end{array}}\right]{\begin{bmatrix}u_{x1}\\u_{y1}\\\hline u_{x2}\\u_{y2}\end{bmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e24897e0a82c5be5f294099a3313717bf11caeb6)