Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Structural analysis

View on Wikipedia| Mechanical failure modes |

|---|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

Structural analysis is a branch of solid mechanics which uses simplified models for solids like bars, beams and shells for engineering decision making. Its main objective is to determine the effect of loads on physical structures and their components. In contrast to theory of elasticity, the models used in structural analysis are often differential equations in one spatial variable. Structures subject to this type of analysis include all that must withstand loads, such as buildings, bridges, aircraft and ships. Structural analysis uses ideas from applied mechanics, materials science and applied mathematics to compute a structure's deformations, internal forces, stresses, support reactions, velocity, accelerations, and stability. The results of the analysis are used to verify a structure's fitness for use, often precluding physical tests. Structural analysis is thus a key part of the engineering design of structures.[1]

Structures and loads

[edit]In the context to structural analysis, a structure refers to a body or system of connected parts used to support a load. Important examples related to Civil Engineering include buildings, bridges, and towers; and in other branches of engineering, ship and aircraft frames, tanks, pressure vessels, mechanical systems, and electrical supporting structures are important. To design a structure, an engineer must account for its safety, aesthetics, and serviceability, while considering economic and environmental constraints. Other branches of engineering work on a wide variety of non-building structures.

Classification of structures

[edit]A structural system is the combination of structural elements and their materials. It is important for a structural engineer to be able to classify a structure by either its form or its function, by recognizing the various elements composing that structure. The structural elements guiding the systemic forces through the materials are not only such as a connecting rod, a truss, a beam, or a column, but also a cable, an arch, a cavity or channel, and even an angle, a surface structure, or a frame.

Loads

[edit]Once the dimensional requirement for a structure have been defined, it becomes necessary to determine the loads the structure must support. Structural design, therefore begins with specifying loads that act on the structure. The design loading for a structure is often specified in building codes. There are two types of codes: general building codes and design codes, engineers must satisfy all of the code's requirements in order for the structure to remain reliable.

There are two types of loads that structure engineering must encounter in the design. The first type of loads are dead loads that consist of the weights of the various structural members and the weights of any objects that are permanently attached to the structure. For example, columns, beams, girders, the floor slab, roofing, walls, windows, plumbing, electrical fixtures, and other miscellaneous attachments. The second type of loads are live loads which vary in their magnitude and location. There are many different types of live loads like building loads, highway bridge loads, railroad bridge loads, impact loads, wind loads, snow loads, earthquake loads, and other natural loads.

Analytical methods

[edit]To perform an accurate analysis a structural engineer must determine information such as structural loads, geometry, support conditions, and material properties. The results of such an analysis typically include support reactions, stresses and displacements. This information is then compared to criteria that indicate the conditions of failure. Advanced structural analysis may examine dynamic response, stability and non-linear behavior. There are three approaches to the analysis: the mechanics of materials approach (also known as strength of materials), the elasticity theory approach (which is actually a special case of the more general field of continuum mechanics), and the finite element approach. The first two make use of analytical formulations which apply mostly simple linear elastic models, leading to closed-form solutions, and can often be solved by hand. The finite element approach is actually a numerical method for solving differential equations generated by theories of mechanics such as elasticity theory and strength of materials. However, the finite-element method depends heavily on the processing power of computers and is more applicable to structures of arbitrary size and complexity.

Regardless of approach, the formulation is based on the same three fundamental relations: equilibrium, constitutive, and compatibility. The solutions are approximate when any of these relations are only approximately satisfied, or only an approximation of reality.

Limitations

[edit]Each method has noteworthy limitations. The method of mechanics of materials is limited to very simple structural elements under relatively simple loading conditions. The structural elements and loading conditions allowed, however, are sufficient to solve many useful engineering problems. The theory of elasticity allows the solution of structural elements of general geometry under general loading conditions, in principle. Analytical solution, however, is limited to relatively simple cases. The solution of elasticity problems also requires the solution of a system of partial differential equations, which is considerably more mathematically demanding than the solution of mechanics of materials problems, which require at most the solution of an ordinary differential equation. The finite element method is perhaps the most restrictive and most useful at the same time. This method itself relies upon other structural theories (such as the other two discussed here) for equations to solve. It does, however, make it generally possible to solve these equations, even with highly complex geometry and loading conditions, with the restriction that there is always some numerical error. Effective and reliable use of this method requires a solid understanding of its limitations.

Strength of materials methods (classical methods)

[edit]The simplest of the three methods here discussed, the mechanics of materials method is available for simple structural members subject to specific loadings such as axially loaded bars, prismatic beams in a state of pure bending, and circular shafts subject to torsion. The solutions can under certain conditions be superimposed using the superposition principle to analyze a member undergoing combined loading. Solutions for special cases exist for common structures such as thin-walled pressure vessels.

For the analysis of entire systems, this approach can be used in conjunction with statics, giving rise to the method of sections and method of joints for truss analysis, moment distribution method for small rigid frames, and portal frame and cantilever method for large rigid frames. Except for moment distribution, which came into use in the 1930s, these methods were developed in their current forms in the second half of the nineteenth century. They are still used for small structures and for preliminary design of large structures.

The solutions are based on linear isotropic infinitesimal elasticity and Euler–Bernoulli beam theory. In other words, they contain the assumptions (among others) that the materials in question are elastic, that stress is related linearly to strain, that the material (but not the structure) behaves identically regardless of direction of the applied load, that all deformations are small, and that beams are long relative to their depth. As with any simplifying assumption in engineering, the more the model strays from reality, the less useful (and more dangerous) the result.

Example

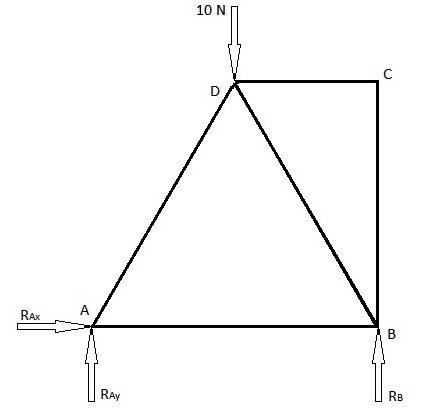

[edit]There are 2 commonly used methods to find the truss element forces, namely the method of joints and the method of sections. Below is an example that is solved using both of these methods. The first diagram below is the presented problem for which the truss element forces have to be found. The second diagram is the loading diagram and contains the reaction forces from the joints.

Since there is a pin joint at A, it will have 2 reaction forces. One in the x direction and the other in the y direction. At point B, there is a roller joint and hence only 1 reaction force in the y direction. Assuming these forces to be in their respective positive directions (if they are not in the positive directions, the value will be negative).

Since the system is in static equilibrium, the sum of forces in any direction is zero and the sum of moments about any point is zero. Therefore, the magnitude and direction of the reaction forces can be calculated.

Method of joints

[edit]This type of method uses the force balance in the x and y directions at each of the joints in the truss structure.

At A,

At D,

At C,

Although the forces in each of the truss elements are found, it is a good practice to verify the results by completing the remaining force balances.

At B,

Method of sections

[edit]This method can be used when the truss element forces of only a few members are to be found. This method is used by introducing a single straight line cutting through the member whose force has to be calculated. However this method has a limit in that the cutting line can pass through a maximum of only 3 members of the truss structure. This restriction is because this method uses the force balances in the x and y direction and the moment balance, which gives a maximum of 3 equations to find a maximum of 3 unknown truss element forces through which this cut is made. Find the forces FAB, FBD and FCD in the above example

Method 1: Ignore the right side

[edit]Method 2: Ignore the left side

[edit]The truss elements forces in the remaining members can be found by using the above method with a section passing through the remaining members.

Elasticity methods

[edit]Elasticity methods are available generally for an elastic solid of any shape. Individual members such as beams, columns, shafts, plates and shells may be modeled. The solutions are derived from the equations of linear elasticity. The equations of elasticity are a system of 15 partial differential equations. Due to the nature of the mathematics involved, analytical solutions may only be produced for relatively simple geometries. For complex geometries, a numerical solution method such as the finite element method is necessary.

Methods using numerical approximation

[edit]It is common practice to use approximate solutions of differential equations as the basis for structural analysis. This is usually done using numerical approximation techniques. The most commonly used numerical approximation in structural analysis is the Finite Element Method.

The finite element method approximates a structure as an assembly of elements or components with various forms of connection between them and each element of which has an associated stiffness. Thus, a continuous system such as a plate or shell is modeled as a discrete system with a finite number of elements interconnected at finite number of nodes and the overall stiffness is the result of the addition of the stiffness of the various elements. The behaviour of individual elements is characterized by the element's stiffness (or flexibility) relation. The assemblage of the various stiffness's into a master stiffness matrix that represents the entire structure leads to the system's stiffness or flexibility relation. To establish the stiffness (or flexibility) of a particular element, we can use the mechanics of materials approach for simple one-dimensional bar elements, and the elasticity approach for more complex two- and three-dimensional elements. The analytical and computational development are best effected throughout by means of matrix algebra, solving partial differential equations.

Early applications of matrix methods were applied to articulated frameworks with truss, beam and column elements; later and more advanced matrix methods, referred to as "finite element analysis", model an entire structure with one-, two-, and three-dimensional elements and can be used for articulated systems together with continuous systems such as a pressure vessel, plates, shells, and three-dimensional solids. Commercial computer software for structural analysis typically uses matrix finite-element analysis, which can be further classified into two main approaches: the displacement or stiffness method and the force or flexibility method. The stiffness method is the most popular by far thanks to its ease of implementation as well as of formulation for advanced applications. The finite-element technology is now sophisticated enough to handle just about any system as long as sufficient computing power is available. Its applicability includes, but is not limited to, linear and non-linear analysis, solid and fluid interactions, materials that are isotropic, orthotropic, or anisotropic, and external effects that are static, dynamic, and environmental factors. This, however, does not imply that the computed solution will automatically be reliable because much depends on the model and the reliability of the data input.

Timeline

[edit]- 1452–1519 Leonardo da Vinci made many contributions

- 1638: Galileo Galilei published the book "Two New Sciences" in which he examined the failure of simple structures

- 1660: Hooke's law by Robert Hooke

- 1687: Isaac Newton published "Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica" which contains the Newton's laws of motion

- 1750: Euler–Bernoulli beam equation

- 1700–1782: Daniel Bernoulli introduced the principle of virtual work

- 1707–1783: Leonhard Euler developed the theory of buckling of columns

- 1826: Claude-Louis Navier published a treatise on the elastic behaviors of structures

- 1873: Carlo Alberto Castigliano presented his dissertation "Intorno ai sistemi elastici", which contains his theorem for computing displacement as partial derivative of the strain energy. This theorem includes the method of 'least work' as a special case

- 1878-1972 Stephen Timoshenko father of modern Applied mechanics including the Timoshenko–Ehrenfest beam theory

- 1936: Hardy Cross' publication of the moment distribution method which was later recognized as a form of the relaxation method applicable to the problem of flow in pipe-network

- 1941: Alexander Hrennikoff submitted his D.Sc. thesis in MIT on the discretization of plane elasticity problems using a lattice framework

- 1942: R. Courant divided a domain into finite subregions

- 1956: J. Turner, R. W. Clough, H. C. Martin, and L. J. Topp's paper on the "Stiffness and Deflection of Complex Structures" introduces the name "finite-element method" and is widely recognized as the first comprehensive treatment of the method as it is known today

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Science Direct: Structural Analysis" Archived 2021-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

Structural analysis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and purpose

Structural analysis is a branch of solid mechanics that employs mathematical models to determine the effects of loads on physical structures and materials, predicting key behaviors such as stress, strain, deformation, and stability.[5][6][7] The primary purpose of structural analysis is to verify that structures, including buildings, bridges, and machines, are safe, serviceable, and economical by assessing their fitness under diverse operating conditions.[8][9][10] Its scope encompasses both static and dynamic responses, as well as linear and nonlinear behaviors, ranging from simple components like beams to intricate systems; it differs from structural design, which uses these analytical results to optimize dimensions and configurations.[11][12] At its core, structural analysis relies on three fundamental principles: equilibrium, which ensures force and moment balance; compatibility, which maintains continuity of deformations; and constitutive relations, such as Hooke's law for linear elastic materials, expressed as , linking stress () to strain () via the modulus of elasticity ().[13][14][6][15] This discipline finds broad applications in civil, mechanical, and aerospace engineering to avert catastrophic failures, as exemplified by the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse, which underscored the critical need for dynamic analysis in design.[16][17] It predicts responses to loads such as dead and live forces on structures like trusses and frames.[5]Classification of structures

Structures in structural analysis are classified based on their geometry, connectivity, material properties, and behavioral characteristics to determine the appropriate methods for predicting internal forces and deformations under loads./01%3A_Chapters/1.01%3A_Introduction_to_Structural_Analysis) This classification aids in simplifying complex real-world systems into models that can be analyzed using equilibrium equations or advanced techniques. One primary criterion is dimensionality, which categorizes structures as one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), or three-dimensional (3D) based on the idealized elements used in modeling.[18] 1D structures consist of line elements like beams, arches, trusses, and frames, where loads are transferred primarily along the length of members./01%3A_Chapters/1.01%3A_Introduction_to_Structural_Analysis) Trusses are pin-jointed frameworks composed of straight members that carry only axial forces, making them efficient for spanning large distances in applications such as roofs and towers, exemplified by the Eiffel Tower's lattice design.[19] Frames feature rigidly connected members that resist bending, shear, and axial loads, commonly used in multi-story buildings and portal structures like rigid frames. Beams and arches serve as spanning elements; beams primarily handle transverse loads through bending, while arches redirect loads via thrust to supports, as seen in bridge designs./01%3A_Chapters/1.01%3A_Introduction_to_Structural_Analysis) 2D structures model surfaces using plate or shell elements, suitable for thin, curved forms that distribute loads over area.[18] Plates are flat or slightly curved elements, such as floor slabs or bridge decks, that primarily experience bending and in-plane stresses.[20] Shells, like domes or tank roofs, combine membrane actions (in-plane stresses) with bending to efficiently cover large areas while resisting pressure or environmental loads. 3D structures represent solid volumes using continuum elements for massive bodies like dams or foundations, where stresses vary in all directions and require full three-dimensional analysis.[18] Another key classification is by determinacy, distinguishing statically determinate from indeterminate structures based on whether equilibrium equations alone suffice to solve for unknown forces./02%3A_Analysis_of_Statically_Determinate_Structures/03%3A_Equilibrium_Structures_Support_Reactions_Determinacy_and_Stability_of_Beams_and_Frames/3.03%3A_Determinacy_and_Stability_of_Beams_and_Frames) Statically determinate structures, such as simple beams or trusses with just enough supports, can have all reactions and internal forces found using the three equilibrium equations (sum of forces and moments equal to zero).[21] Indeterminate structures, like continuous beams or fixed frames, possess redundancy, requiring additional compatibility conditions or deformation analysis to resolve extra unknowns.[22] Structures are also classified by material composition: homogeneous structures have uniform properties throughout, simplifying stress calculations, whereas composite structures integrate multiple materials, such as steel-reinforced concrete, to optimize strength and weight.[20] From a behavioral perspective, structures are assessed for stability and redundancy; stable structures maintain equilibrium under loads without excessive deformation or collapse, while unstable ones, like mechanisms with insufficient constraints, fail to resist motion./02%3A_Analysis_of_Statically_Determinate_Structures/03%3A_Equilibrium_Structures_Support_Reactions_Determinacy_and_Stability_of_Beams_and_Frames/3.03%3A_Determinacy_and_Stability_of_Beams_and_Frames) Redundant systems offer backup load paths for enhanced reliability, contrasting simple systems that lack such provisions but are easier to analyze.[21]Types of loads

In structural analysis, loads represent the external forces and influences applied to a structure, which must be identified, quantified, and combined to evaluate the structure's response under various conditions. These loads are categorized based on their origin, variability, and duration, ensuring that designs account for both normal usage and extreme events as prescribed by building codes. The primary types include dead loads, live loads, environmental loads, seismic loads, and other specialized loads, with analysis requiring consideration of how these forces transfer through the structure via defined load paths. Dead loads consist of the permanent, constant weights inherent to the structure and its fixed components, such as the self-weight of beams, columns, floors, and roofing materials, as well as attached equipment like HVAC systems or plumbing. These loads are calculated by multiplying the material density by the volume or cross-sectional area of the elements, providing a predictable, unchanging contribution to the total loading that forms the baseline for all analyses.[23] Live loads are variable forces resulting from occupancy, usage, or temporary installations, including the weight of people, furniture, vehicles, or movable equipment in buildings and bridges. Unlike dead loads, live loads fluctuate in magnitude and distribution, and their design values are stipulated by standards such as ASCE 7, which specifies minimum uniform and concentrated loads based on occupancy categories—for instance, 40 psf for office floors or 100 psf for light manufacturing areas—to ensure safety under anticipated conditions.[24][23] Environmental loads arise from natural phenomena and include wind, snow or ice accumulation, and temperature variations. Wind loads are induced by air movement exerting dynamic pressure on exposed surfaces, fundamentally derived from the velocity pressure formula , where is air density and is wind speed, though engineering codes adjust this with factors for terrain, height, and topography to compute site-specific pressures. Snow and ice loads represent the weight of accumulated precipitation or frozen water on roofs, with design values in ASCE 7 based on geographic ground snow loads mapped for regions, often ranging from 20 to 50 psf in moderate climates. Temperature changes induce thermal loads through expansion or contraction, modeled by the linear thermal expansion equation , where is the coefficient of thermal expansion, is the original length, and is the temperature change, potentially causing significant stresses in restrained members like bridges or long-span roofs.[24][25][26] Seismic loads stem from earthquake-induced ground accelerations that impart inertial forces to the structure, equivalent to dynamic excitations translated into static equivalents for simplified analysis. The basic equivalent static force is given by , where is the mass and is the effective ground acceleration, often scaled by seismic response coefficients from site-specific hazard maps in codes like ASCE 7; more advanced methods use response spectra to capture frequency-dependent effects, but the static approach applies to regular, low- to mid-rise structures.[24][27] Other loads encompass less common but critical forces such as impact from moving objects like vehicles on bridges, blast pressures from explosions, and fluid pressures in retaining walls or tanks. Impact loads account for sudden dynamic applications, often amplified by factors in codes to simulate kinetic energy transfer. Blast loads involve high-intensity, short-duration pressures modeled similarly to wind but with nonlinear shock wave propagation. Fluid pressures, particularly hydrostatic, follow , where is fluid density, is gravity, and is depth below the surface, essential for dams, reservoirs, or underground structures where water exerts lateral forces proportional to submersion.[23][28] Load combinations integrate multiple load types to represent realistic worst-case scenarios, distinguishing between strength (ultimate) limits for safety against failure and serviceability limits for functionality like deflection control. Per ASCE 7, ultimate combinations for load and resistance factor design (LRFD) include equations such as 1.4D for dead loads alone or 1.2D + 1.6L + 0.5S for dead, live, and snow loads, applying factors greater than 1.0 to variable loads to account for uncertainty and simultaneity probabilities. These ensure the structure's capacity exceeds the amplified demand under probable concurrent actions.[24][29] Load paths describe the sequence of structural elements through which forces transfer from application points to supports, crucial for distributing loads efficiently and verifying member capacities. Tributary areas define the surface area contributing load to a specific element, such as half the span between beams for a floor joist, enabling proportional load assignment—for example, a column might carry the tributary area of its supported bays multiplied by the uniform load intensity—to trace vertical and lateral force flow in frames or slabs.[30]Classical methods

Strength of materials approaches

Strength of materials approaches encompass classical analytical methods used in structural analysis to determine internal forces, stresses, and deformations in simple structures, relying on fundamental principles of equilibrium and material behavior. These methods, foundational to engineering practice since the early 20th century, simplify complex continuum problems into one-dimensional or two-dimensional models suitable for hand calculations. They are particularly effective for statically determinate structures and extendable to mildly indeterminate ones through compatibility conditions. Seminal contributions, such as those in Stephen Timoshenko's Strength of Materials (Parts I and II, 1930), established these techniques by integrating elasticity theory with practical engineering approximations. Central to these approaches are key assumptions that enable tractable solutions: linear elasticity, where stress is proportional to strain via Hooke's law; small deformations, neglecting higher-order geometric nonlinearities; homogeneous and isotropic materials; and the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory, which posits that plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis after deformation. These assumptions reduce three-dimensional elasticity problems to beam, truss, or frame models, focusing on axial, shear, and bending effects. For instance, in beam theory, the relationship between shear force and bending moment is given by , and the moment-curvature relation is , where is the modulus of elasticity, is the moment of inertia, and is the deflection.[31][32] For statically determinate structures, analysis relies solely on equilibrium equations (, ) to solve for reactions and internal forces without needing deformation compatibility. In beams, this involves constructing shear and moment diagrams to visualize force distributions under applied loads, such as dead or live loads. Trusses, idealized as pin-jointed frameworks carrying only axial forces, are analyzed using the method of joints or sections. The method of joints isolates each pin connection, resolving forces in two directions via equilibrium to find member axial loads sequentially from supports outward. For example, in a simple roof truss with vertical loads at joints, starting at a support joint with known reaction allows computation of adjacent member forces, propagating through the structure. The method of sections complements this by cutting through the truss to expose a subset of members, applying equilibrium to a free-body diagram of one portion for targeted force determination in non-adjacent members. These techniques confirm determinacy when the number of members satisfies for plane trusses, where is the number of joints./02:_Analysis_of_Statically_Determinate_Structures/05:_Internal_Forces_in_Plane_Trusses/5.06:_Methods_of_Truss_Analysis)[33] Indeterminate structures, where equilibrium equations alone are insufficient, require additional compatibility conditions to relate deformations across redundancies. Methods like slope-deflection and moment distribution enforce continuity of rotations and displacements. In the slope-deflection approach, end moments in a beam member are expressed as , where and are end rotations, is the length, and is the chord rotation due to support settlement. The moment distribution method, developed by Hardy Cross in 1930, iteratively distributes unbalanced moments at joints based on relative stiffnesses until equilibrium is achieved, ideal for hand analysis of frames./01:_Chapters/1.12:_Moment_Distribution_Method_of_Analysis_of_Structures) Beam deflection analysis extends these methods by integrating the moment equation. The double integration technique yields the deflection curve as , where constants and are determined from boundary conditions, such as zero deflection and slope at supports. The conjugate beam method analogizes the real beam's diagram to a load on an imaginary conjugate beam, where shear and moment in the conjugate represent slope and deflection in the original. These provide exact solutions for prismatic beams under simple loading./02:_Analysis_of_Statically_Determinate_Structures/07:_Deflection_of_Beams-_Geometric_Methods/7.03:_Deflection_by_Method_of_Double_Integration)[34] Despite their utility, strength of materials approaches have limitations: they apply primarily to prismatic members with uniform cross-sections and simple geometries, assuming one-dimensional stress states that overlook three-dimensional effects like stress concentrations or torsion in complex shapes. They are less accurate for non-homogeneous materials or large deformations, where full elasticity solutions are needed. Timoshenko noted these constraints in his historical survey, emphasizing their role as engineering approximations rather than precise continuum analyses.[35]Elasticity methods

Elasticity methods provide a rigorous framework for analyzing stress and strain distributions in continuous media under the assumptions of linear elasticity, offering more precise solutions than simplified engineering approximations for complex geometries and loading conditions. These methods solve the complete boundary value problems of the theory of linear elasticity, incorporating the fundamental equations derived from equilibrium, compatibility, and constitutive relations. The equilibrium equation in the absence of body forces is given by ∇·σ = 0, where σ is the stress tensor, while body forces b are included as ∇·σ + b = 0.[36] The strain-displacement compatibility condition ensures the strain tensor ε is symmetric and derives from the displacement field u as ε_ij = (1/2)(∂u_i/∂x_j + ∂u_j/∂x_i).[37] For isotropic linear elastic materials, Hooke's law relates stresses and strains via σ_ij = λ δ_ij ε_kk + 2μ ε_ij, where λ and μ are the Lamé constants, δ_ij is the Kronecker delta, and summation over repeated indices k is implied.[36] Combining these yields Navier's equations for the displacement field: μ ∇²u + (λ + μ) ∇(∇·u) + b = 0, which govern the deformation in three dimensions.[37] In two-dimensional problems, elasticity methods distinguish between plane stress and plane strain states to simplify analysis for thin or long structures. Plane stress assumes σ_z = 0 and all derivatives with respect to z are zero, applicable to thin plates where out-of-plane stresses are negligible, leading to effective moduli adjusted by Poisson's ratio.[38] Plane strain assumes ε_z = 0 and ∂/∂z = 0, suitable for long cylinders constrained against axial deformation, resulting in σ_z = ν(σ_x + σ_y) from Hooke's law.[39] For both cases, the Airy stress function φ(x, y) introduces stresses as σ_x = ∂²φ/∂y², σ_y = ∂²φ/∂x², and σ_xy = -∂²φ/∂x∂y, automatically satisfying equilibrium in the plane.[38] Substituting into the compatibility equation yields the biharmonic governing equation ∇⁴φ = 0 for plane stress and plane strain alike, independent of material properties.[39] Exact analytical solutions to elasticity equations are feasible for specific geometries and loads, providing benchmarks for more general methods. For a thick-walled cylinder under internal and external pressure, Lame's solution gives the radial stress as σ_r = A - B/r² and hoop stress as σ_θ = A + B/r², where A and B are constants determined from boundary conditions at inner radius a and outer radius b, such as σ_r(a) = -p_i and σ_r(b) = -p_o.[40] This radial distribution highlights how maximum tensile hoop stresses occur at the inner surface, critical for pressure vessel design. For torsion of prismatic bars with non-circular cross-sections, the Prandtl stress function ψ(x, y) defines shear stresses as τ_xz = ∂ψ/∂y and τ_yz = -∂ψ/∂x, satisfying equilibrium and leading to the Poisson equation ∇²ψ = -2μθ, where θ is the twist per unit length.[41] The torque T relates to the volume integral of ψ over the cross-section as T = 2 ∫ψ dA, enabling computation of warping and stress fields for shapes like ellipses or rectangles.[41] Energy methods in elasticity exploit variational principles to derive solutions or approximate displacements without directly solving differential equations. The principle of minimum potential energy states that among all kinematically admissible displacement fields, the actual solution minimizes the total potential Π = U - W, where U is the strain energy ∫(1/2)σ_ij ε_ij dV and W is the work of external loads; stationarity requires δΠ = 0.[42] Castigliano's theorem, a corollary, computes deflections as the partial derivative of the strain energy with respect to a load: δ_i = ∂U/∂P_i for the displacement δ_i at the point of application of force P_i, assuming conservative loads and linear elasticity.[43] These approaches are particularly useful for statically indeterminate structures, where compatibility is enforced through energy minimization. Boundary value problems in elasticity often employ semi-inverse methods, assuming forms for displacements or stresses that partially satisfy equations and boundaries, then solving for remaining unknowns. Saint-Venant's principle asserts that the exact solution to a boundary value problem is approached by solutions to the reduced Saint-Venant problem—where only resultant forces and moments are specified on the ends—sufficiently far from the loaded boundaries, as local perturbations decay exponentially with distance.[44] This justifies approximations in long members, such as beams, where end effects are negligible beyond a characteristic length proportional to the cross-sectional dimension.[45] Applications of elasticity methods include analyzing stress concentrations around holes, notches, or inclusions, where the Airy function or complex potentials reveal amplification factors up to three for circular holes in uniaxial tension under plane stress.[38] Thermal stresses in solids arise from temperature gradients inducing incompatible strains, solved by extending Hooke's law to include thermal terms ε_ij^thermal = α ΔT δ_ij, with α the coefficient of thermal expansion; for example, in a constrained plate, uniform heating produces compressive stresses σ = -E α ΔT.[46] These methods refine the beam and truss approximations from strength of materials by capturing full three-dimensional effects in continuous bodies.[36]Numerical methods

Finite element method

The finite element method (FEM) is a numerical technique widely used in structural analysis to approximate solutions to boundary value problems by dividing a continuous structure into a finite number of discrete elements connected at nodes. This discretization allows for the modeling of complex geometries and loading conditions that are intractable with classical analytical methods. The method approximates the displacement field within each element using interpolation functions, leading to a system of algebraic equations that can be solved for nodal displacements and subsequently derived quantities like stresses and strains.[47] In the displacement-based formulation, the primary unknowns are the nodal displacements , which relate to applied forces through the global stiffness matrix via the equation . Within each element, displacements are interpolated from nodal values using shape functions , such that the displacement at any point is , where are the element nodal displacements. For a simple one-dimensional linear element, the shape function is given by and , with as the natural coordinate ranging from -1 to 1. The strain-displacement matrix is derived from the derivatives of these shape functions, and the element stiffness matrix is computed as , where is the material constitutive matrix and the integral is over the element volume.[47] Common element types in structural analysis include one-dimensional truss and beam elements for simplified frameworks, two-dimensional plane stress or plane strain elements for thin structures under in-plane loading, and three-dimensional solid elements like tetrahedra for volumetric solids. Isoparametric elements extend this capability by using the same shape functions to interpolate both displacements and geometry, enabling accurate representation of curved boundaries; for instance, a four-node quadrilateral element maps from a square parent domain in natural coordinates to an arbitrary quadrilateral in physical space via . These formulations ensure compatibility between elements and allow for higher-order approximations when needed.[47][48] The global system is assembled by summing the contributions of all element stiffness matrices , typically using the Galerkin weighted residual method to derive the weak form of the governing equilibrium equations , where are body forces and are surface tractions. Boundary conditions are applied as essential (displacement-specified, modifying and ) or natural (force-specified, entering the vector). The resulting linear system is solved using direct or iterative solvers for the nodal displacements.[47] Post-processing involves recovering derived quantities, such as stresses at element interiors or nodes, often with averaging or extrapolation for smoother fields. Solution accuracy improves through mesh refinement strategies: h-refinement by decreasing element size to increase resolution, or p-refinement by increasing the polynomial order of shape functions for exponential convergence in smooth problems. These approaches ensure reliable results for linear static analysis in engineering practice.[47][49] Recent advancements as of 2025 integrate artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into FEM to enhance efficiency and accuracy. AI-enhanced FEM uses deep learning to accelerate meshing, surrogate modeling, and error estimation, achieving up to 1-3% improved accuracy in complex simulations while reducing computational time. Commercial software like ANSYS has incorporated AI assistants for automated analysis workflows in its 2025 R2 release.[50][51] In modern structural analysis, FEM is implemented in various software packages, including commercial tools like ANSYS for comprehensive multiphysics simulations and SAP2000 for building and bridge design, which automate meshing, assembly, and solution for linear static problems. Open-source alternatives such as FEniCS provide flexible, Python-based platforms for custom implementations, supporting research and education in FEM applications. These tools have become essential for simulating real-world structures under diverse loads.[52][53][54]Other approximation techniques

The finite difference method (FDM) approximates derivatives in partial differential equations governing structural behavior by replacing them with discrete differences on a structured grid, making it particularly suitable for problems with regular geometries such as plates and beams. A common central difference approximation for the second derivative is given by where is the displacement at node and is the grid spacing; this formulation enables straightforward implementation for linear elastic problems but requires careful grid refinement to minimize truncation errors.[55] In structural mechanics, FDM has been applied to analyze beam vibrations and plate bending, offering computational simplicity for one- and two-dimensional domains where boundary conditions align with the grid.[56] The boundary element method (BEM) formulates structural problems using integral equations defined solely on the domain boundaries, reducing the dimensionality of the discretization from volume to surface elements and thereby decreasing the number of degrees of freedom compared to domain-based methods. This approach relies on fundamental solutions like the Kelvin solution for potential fields, which represents the Green's function for point loads in infinite elastic media, allowing efficient handling of boundary tractions and displacements.[57] BEM excels in scenarios involving infinite or semi-infinite domains, such as soil-structure interaction, where it naturally incorporates far-field radiation without artificial boundaries.[58] Meshless methods, also known as mesh-free techniques, approximate field variables using scattered nodes without a predefined connectivity mesh, avoiding mesh distortion issues common in large-deformation analyses. Key variants include the element-free Galerkin method (EFGM), which employs moving least-squares approximations for shape functions, and smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH), which uses kernel-based interpolation for continuum mechanics. These methods are advantageous for adaptive refinement in fracture propagation or impact simulations in structures, as nodes can be easily added or removed without remeshing.[59] Spectral methods leverage global basis functions, such as Fourier series, to represent solutions in periodic or smooth domains, achieving exponential convergence for vibration modes and wave propagation in structures with high accuracy using fewer degrees of freedom than local approximations. In the spectral transfer matrix method, for instance, exact dynamic stiffness matrices derived from frequency-domain solutions are combined with transfer matrices to analyze periodic one-dimensional structures like truss lattices, enabling efficient computation of eigenfrequencies via fast Fourier transforms.[60] This approach is particularly effective for modal analysis of beams and plates where solutions are analytic and smooth, outperforming polynomial-based methods in capturing high-frequency responses. Isogeometric analysis (IGA) represents another advanced numerical technique that uses the same non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS) basis functions for both geometric representation and solution approximation, bridging computer-aided design (CAD) and finite element analysis (FEA). This integration allows higher-order continuity and exact geometry representation without meshing approximations, improving accuracy in structural simulations of complex shapes like shells and beams. As of 2025, IGA has gained prominence in optimization and multiphysics problems, with ongoing developments in adaptive refinement and coupling with other methods.[61][62] Hybrid approaches integrate multiple techniques to exploit their complementary strengths, such as coupling FEM for near-field structural details with BEM for surrounding infinite media in embedded foundation problems. For example, in dynamic soil-structure interaction, the FEM domain models the nonlinear structure while BEM handles the elastic half-space, reducing overall computational demands through interface matching of displacements and tractions.[63] These hybrids are selected over pure FEM when boundary effects dominate, as in acoustics or electromagnetics applications extending to structural vibrations, where BEM's fewer degrees of freedom yield up to 50% reduction in solution time for scattering problems.[64]Advanced considerations

Limitations and assumptions

Structural analysis methods rely on several simplifying assumptions to make complex engineering problems tractable. A primary assumption is material linearity, where stresses and strains are proportional according to Hooke's law, enabling the principle of superposition for combining load effects. This holds only within the elastic range, excluding plastic behavior or unloading paths. Additionally, analyses assume small deformations and strains, neglecting geometric nonlinearities that arise from large displacements altering the structure's equilibrium configuration. Materials are commonly idealized as isotropic and homogeneous, with uniform properties in all directions and throughout the body, which simplifies constitutive relations but deviates from anisotropic composites or graded materials. Supports and joints are treated as ideal, such as frictionless pins or rigid clamps, ignoring real imperfections like partial fixity or wear.[65][66][67][68] Sources of error in structural analysis stem from approximations in modeling and computation. For dynamic problems, representing distributed mass as lumped point masses simplifies equations but can introduce inaccuracies in wave propagation or higher-mode responses compared to continuous distributions. In numerical approaches like the finite element method, discretization errors arise from element size and shape, necessitating mesh refinement to achieve convergence where solution errors diminish with finer grids. Boundary condition approximations, such as assuming uniform soil restraint instead of measured stiffness, further propagate uncertainties into stress and deflection predictions. These errors compound in complex geometries, potentially leading to over- or underestimation of capacities by 10-20% without proper verification.[69][70] In indeterminate structures, determinacy issues manifest as ill-conditioned systems, where the stiffness matrix becomes nearly singular due to redundant constraints or near-mechanisms, amplifying numerical errors from rounding or perturbations. Singularity occurs explicitly if degrees of freedom are unconstrained, resulting in infinite displacements or zero eigenvalues, which solvers detect but require regularization like master-slave constraints to resolve. Such conditions are prevalent in frames with flexible connections or soil-structure interactions, demanding careful conditioning checks via condition numbers exceeding 10^6 signaling instability.[71][72] Validation ensures reliability by cross-checking analytical results against physical tests, such as deploying strain gauges to measure local deformations under controlled loads and comparing them to predicted values, often achieving correlations within 5-15% for well-modeled systems. Sensitivity analysis quantifies impacts of parameter variations, like material modulus or load eccentricity, revealing vulnerabilities where a 10% change in input yields disproportionate output shifts. These techniques highlight modeling flaws, guiding refinements before design finalization.[73][74] Compliance with standards like Eurocodes mandates incorporating partial safety factors to address uncertainties in actions, geometries, and resistances, with EN 1990 specifying values like 1.35 for permanent loads and 1.5 for variables to achieve target reliability indices of 3.8 over 50 years. These factors embed safety margins against epistemic and aleatory uncertainties, ensuring analyses align with probabilistic limits rather than deterministic ideals, though they may conservatively inflate designs by 20-30% in low-risk scenarios.[75][76] Traditional structural analysis methods provide incomplete coverage for time-dependent phenomena, often ignoring viscous damping in dynamic responses, which underpredicts energy dissipation and overestimates resonant amplitudes in seismic or wind events. Similarly, creep under sustained loads is frequently overlooked, causing unaccounted deformations in concrete structures that can accumulate to 130–410% of the initial elastic deflections over decades, compromising serviceability without advanced viscoelastic models.[77]Nonlinear and dynamic analysis

Nonlinear structural analysis extends linear methods to account for large deformations and material behaviors that violate the assumptions of small strains and linear elasticity, enabling the prediction of failure modes in complex loading scenarios. Geometric nonlinearity arises when deformations are sufficiently large that the geometry of the structure changes significantly, affecting stiffness and load paths; this is particularly relevant for flexible structures like cable nets and membranes where initial assumptions of small displacements lead to inaccurate results. In such cases, formulations like the updated Lagrangian approach are employed, which incrementally update the reference configuration at each load step to compute strains relative to the current deformed state, thereby capturing effects like membrane action in shells. Material nonlinearity occurs when stresses exceed the elastic limit, leading to permanent deformations or time-dependent responses; plasticity models, such as the von Mises yield criterion, define the onset of yielding based on the distortion energy, given by , where are principal stresses and is the yield stress. This criterion, originally formulated by Richard von Mises, is widely used for ductile metals in structural components under multiaxial loading.[78] For time-dependent behaviors, viscoelastic models like the Kelvin-Voigt representation combine elastic and viscous elements in parallel, expressed as , where is the elastic modulus, is the viscosity, is stress, and is strain; this model effectively describes creep and relaxation in materials such as polymers or concrete under sustained loads.[79] Dynamic analysis incorporates time-varying loads and inertial effects, transforming static equilibrium into dynamic equations via d'Alembert's principle, which introduces fictitious inertia forces as to balance applied loads, allowing the use of equilibrium methods for time-dependent problems like vibrations or impacts. Modal analysis further simplifies this by solving the generalized eigenvalue problem , where is the stiffness matrix, is the mass matrix, are natural frequencies, and are mode shapes; this decomposition enables efficient computation of free vibration responses and forms the basis for response spectrum methods in design.[80] Time integration schemes are essential for solving these dynamic equations numerically, with implicit methods like the Newmark- algorithm providing unconditional stability for larger time steps in nonlinear problems; the displacement update is given by where and yield the average acceleration method, commonly used for earthquake simulations to capture damping without numerical dissipation. Explicit methods, such as central difference, offer computational efficiency for short-duration events like blasts but require smaller time steps to maintain stability.[81] Buckling analysis addresses instability under compressive loads, with the critical load for an ideal Euler column determined by the eigenvalue solution , where is the modulus of elasticity, is the moment of inertia, and is the effective length; this linear bifurcation point is extended in nonlinear analysis to trace post-buckling paths, revealing snap-through or stable equilibrium branches in imperfect structures. Nonlinear extensions build on finite element methods by incorporating geometric stiffness matrices to model these paths accurately.[82] These techniques find critical applications in seismic design, where nonlinear finite element solvers perform response history analysis to simulate ground motion effects, accounting for soil-structure interaction and material degradation to assess collapse risks in buildings and bridges. For blast-resistant structures, dynamic nonlinear models predict localized failures from high-intensity, short-duration loads, guiding reinforcement strategies in military and industrial facilities.[83]Historical development

Key milestones

The origins of structural analysis lie in the empirical practices of ancient civilizations, where builders relied on observational knowledge and geometric intuition to achieve stability in large-scale constructions. In ancient Egypt, around 3000 BCE, pyramid builders employed massive limestone and granite blocks, carefully aligned and stacked using ramps and levers, demonstrating an intuitive grasp of load distribution and compressive strength without theoretical frameworks. Similarly, Roman engineers from the 1st century BCE to 100 CE mastered arch and vault systems in structures like aqueducts and the Colosseum, utilizing voussoir arrangements and concrete infill to transfer loads efficiently through compression, marking a practical evolution in understanding force paths. These methods, honed through iterative construction and failure analysis, laid the groundwork for later scientific approaches by emphasizing proportion and material limits.[84][85] The transition to theoretical foundations occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries, as mechanics emerged as a discipline. In 1638, Galileo Galilei introduced the first analytical treatment of beam strength in his Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, modeling cantilever beams as rigid levers resisting bending through material resistance below the neutral axis, which shifted analysis from pure geometry to considering internal stresses. This work influenced subsequent studies on material behavior under load. Building on this, Leonhard Euler in 1744 derived the critical buckling load formula for slender columns in his treatise Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas, establishing as a cornerstone for stability theory and enabling predictions of failure in compressive members. Euler's contribution transformed structural design by quantifying instability risks, impacting bridge and column engineering. The 19th century saw the formalization of continuum mechanics, with elasticity theory providing rigorous tools for stress and deformation analysis. Claude-Louis Navier developed the fundamental equations of linear elasticity in the 1820s, particularly in his 1821 memoir, which expressed equilibrium in terms of displacement fields and enabled solutions for continuous media like beams and plates. This framework unified disparate empirical rules into a mathematical system. Adhémar Jean Claude Barré de Saint-Venant advanced boundary effect understanding in 1855 with his principle stating that stress distributions away from boundaries depend only on loads, not exact boundary shapes, simplifying practical computations for long members. Later, Otto Mohr introduced the stress circle in 1882 to graphically represent plane stress states, facilitating visualization and calculation of principal stresses and maximum shear, which became essential for material failure assessment. Meanwhile, Carlo Alberto Castigliano's second theorem of 1879, relating strain energy to displacements, offered an energy-based method for indeterminate structures, promoting efficient variational approaches. These developments elevated structural analysis from statics to a predictive science, supporting the industrial era's iron and steel constructions. In the early 20th century, methods for indeterminate structures gained prominence amid growing complexity in building designs. Although formulated in 1879, Castigliano's energy theorems found widespread application post-1900 in solving statically indeterminate frames via complementary energy minimization. A pivotal practical breakthrough came in 1930 with Hardy Cross's moment distribution method, which iteratively balanced moments in continuous beams and frames without solving large equation sets, revolutionizing manual analysis for multi-story buildings and bridges by reducing computational tedium. This technique democratized advanced analysis, influencing reinforced concrete design standards. The mid-20th century marked the shift to numerical and computational paradigms, driven by wartime needs and emerging technology. Richard Courant in 1943 pioneered finite difference approximations in variational methods, discretizing differential equations over grids to solve elasticity problems like torsion, laying conceptual groundwork for numerical simulation in irregular geometries. The 1950s introduction of digital computers revolutionized matrix-based analysis; pioneers like John Argyris developed stiffness matrix methods for aircraft frames using energy principles on early machines like the Manchester Mark 1, enabling automated solution of large systems that manual methods could not handle. This era's matrix structural analysis, as outlined in works from 1954 onward, integrated flexibility and stiffness approaches, scaling up to complex trusses and shells. Modern advancements integrated numerical methods with design tools, culminating in the finite element method's (FEM) standardization. Olek Zienkiewicz's 1967 textbook The Finite Element Method in Structural and Continuum Mechanics synthesized discrete element formulations into a general framework, popularizing FEM for diverse applications from solids to fluids and establishing it as the dominant tool for engineering simulation. From the 1980s onward, integration with computer-aided design (CAD) and building information modeling (BIM) enhanced workflow; CAD systems like AutoCAD facilitated 2D/3D drafting linked to analysis software, while BIM in the 1990s added parametric data for iterative structural optimization, improving accuracy and collaboration in large projects. These fusions transformed structural analysis from isolated calculations to holistic digital processes.[86]Timeline

- 1638: Galileo Galilei's Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche intorno a Due Nuove Scienze introduced foundational concepts of beam bending, marking an early scientific approach to structural strength.[87]

- 1744: Leonhard Euler published his theory of column buckling in Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas maximi minimive proprietate gaudentes, establishing the critical load for elastic instability in slender columns.[88]

- 1826: Claude-Louis Navier's memoir and book Résumé des leçons données à l'École royale des ponts et chaussées presented the general equations of linear elasticity, linking stress and strain for continuous media.[89]

- 1855: Adhémar Jean Claude Barré de Saint-Venant solved the torsion problem for prismatic bars using the semi-inverse method in elasticity theory, deriving the warping function and shear stress distribution.

- 1914: Stephen Timoshenko developed the beam theory accounting for shear deformation and rotary inertia, published in Bulletin of the Polytechnic Institute in St. Petersburg, improving accuracy for short and thick beams over Euler-Bernoulli assumptions.[90]

- 1930: Hardy Cross invented the moment distribution method for approximate analysis of continuous beams and frames, revolutionizing indeterminate structural design in practice.

- 1941: Arpad Hrennikoff introduced the lattice analogy method for analyzing grid structures, serving as a precursor to finite element concepts by discretizing continua into analogous frameworks.

- 1943: Richard Courant proposed a discretization technique for plane stress problems using triangular elements in his paper on variational methods, laying groundwork for the finite element method.

- 1956: M. J. Turner, R. W. Clough, H. C. Martin, and L. J. Topp coined the term "finite element method" in their paper "Stiffness and Deflection Analysis of Complex Structures" presented at the Journal of the Aeronautical Sciences, applying it to aircraft structures at Boeing.

- 1967: Olek C. Zienkiewicz published The Finite Element Method in Structural and Continuum Mechanics, the first comprehensive book on FEM, standardizing its application across engineering disciplines.

- 1970s: The finite element method saw widespread adoption through commercial software, exemplified by NASA's NASTRAN (launched in 1970), enabling complex aerospace structural simulations.

- 1980s: Commercial finite element codes incorporated nonlinear analysis routines, allowing simulation of material and geometric nonlinearities in structures under large deformations.

- 1990s: Standardization of response spectrum methods advanced dynamic analysis for seismic loading, integrating probabilistic seismic hazard assessments into structural design codes.

- 2000s: Building Information Modeling (BIM) integrated with structural analysis tools, facilitating seamless data exchange for design optimization and lifecycle management.

- 2010s-2020s: Artificial intelligence and machine learning emerged for surrogate modeling and optimization in structural analysis, accelerating simulations and enabling predictive maintenance through data-driven approaches.