Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Django (web framework)

View on Wikipedia

| Django | |

|---|---|

| |

| Original authors | Adrian Holovaty, Simon Willison |

| Developer | Django Software Foundation[1] |

| Initial release | 21 July 2005[2] |

| Stable release | |

| Written in | Python[1] |

| Type | Web framework[1] |

| License | 3-clause BSD[5] |

| Website | www |

| Repository | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Python |

|---|

|

Django (/ˈdʒæŋɡoʊ/ JANG-goh; sometimes stylized as django)[6] is a free and open-source, Python-based web framework that runs on a web server. It follows the model–template–views (MTV) architectural pattern.[7][8] It is maintained by the Django Software Foundation (DSF), an independent organization established in the US as a 501(c)(3) non-profit.

Django's primary goal is to ease the creation of complex, database-driven websites. The framework emphasizes reusability and "pluggability" of components, less code, low coupling, rapid development, and the principle of don't repeat yourself.[9] Python is used throughout, even for settings, files, and data models. Django also provides an optional administrative create, read, update and delete interface that is generated dynamically through introspection and configured via admin models.

Some well-known sites that use Django include Instagram,[10] Mozilla,[11] Disqus,[12] Bitbucket,[13] Nextdoor,[14] and Clubhouse.[15]

History

[edit]Django was created in the autumn of 2003, when the web programmers at the Lawrence Journal-World newspaper, Adrian Holovaty and Simon Willison, began using Python to build applications. Jacob Kaplan-Moss was hired early in Django's development shortly before Willison's internship ended.[16] It was released publicly under a BSD license in July 2005. The framework was named after guitarist Django Reinhardt.[17] Holovaty is a romani jazz guitar player inspired in part by Reinhardt's music.[18]

In June 2008, it was announced that a newly formed Django Software Foundation (DSF) would maintain Django in the future.[19]

Features

[edit]Components

[edit]

Despite having its own nomenclature, such as naming the callable objects generating the HTTP responses "views",[7] the core Django framework can be seen as an MVC architecture.[8] It consists of an object-relational mapper (ORM) that mediates between data models (defined as Python classes) and a relational database ("Model"), a system for processing HTTP requests with a web templating system ("View"), and a regular-expression-based URL dispatcher ("Controller").

Also included in the core framework are:

- a lightweight and standalone web server for development and testing

- a form serialization and validation system that can translate between HTML forms and values suitable for storage in the database

- a template system that utilizes the concept of inheritance borrowed from object-oriented programming

- a caching framework that can use any of several cache methods

- support for middleware classes that can intervene at various stages of request processing and carry out custom functions

- an internal dispatcher system that allows components of an application to communicate events to each other via pre-defined signals

- an internationalization system, including translations of Django's own components into a variety of languages

- a serialization system that can produce and read XML and/or JSON representations of Django model instances

- a system for extending the capabilities of the template engine

- an interface to Python's built-in unit test framework

Bundled applications

[edit]The main Django distribution also bundles a number of applications in its "contrib" package, including:

- an extensible authentication system

- the dynamic administrative interface

- tools for generating RSS and Atom syndication feeds

- a "Sites" framework that allows one Django installation to run multiple websites, each with their own content and applications

- tools for generating Sitemaps

- built-in mitigation for cross-site request forgery, cross-site scripting, SQL injection, password cracking and other typical web attacks, most of them turned on by default[20][21]

- a framework for creating geographic information system (GIS) applications

Extensibility

[edit]Django's configuration system allows third-party code to be plugged into a regular project, provided that it follows the reusable app[22] conventions. More than 5000 packages[23] are available to extend the framework's original behavior, providing solutions to issues the original tool didn't tackle: registration, search, API provision and consumption, CMS, etc.

This extensibility is, however, mitigated by internal components' dependencies. While the Django philosophy implies loose coupling,[24] the template filters and tags assume one engine implementation, and both the auth and admin bundled applications require the use of the internal ORM. None of these filters or bundled apps are mandatory to run a Django project, but reusable apps tend to depend on them, encouraging developers to keep using the official stack in order to benefit fully from the apps ecosystem.[25]

Server arrangements

[edit]Django can be run on ASGI or WSGI-compliant web servers.[26] Django officially supports five database backends: PostgreSQL, MySQL, MariaDB, SQLite, and Oracle.[27] Microsoft SQL Server can be used with mssql-django.

Version history

[edit]The Django team will occasionally designate certain releases to be "long-term support" (LTS) releases.[28] LTS releases will get security and data loss fixes applied for a guaranteed period of time, typically 3+ years, regardless of the pace of releases afterwards.

| Version | Release date[29] | End of mainstream support | End of extended support | Notes[30] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.90[31] | 16 Nov 2005 | |||

| 0.91[32] | 11 Jan 2006 | "new-admin" | ||

| 0.95[33] | 29 Jul 2006 | "magic removal" | ||

| 0.96[34] | 23 Mar 2007 | "newforms", testing tools | ||

| 1.0[35] | 3 Sep 2008 | API stability, decoupled admin, unicode | ||

| 1.1[36] | 29 Jul 2009 | Aggregates, transaction based tests | ||

| 1.2[37] | 17 May 2010 | Multiple db connections, CSRF, model validation | ||

| 1.3[38] | 23 Mar 2011 | 23 Mar 2012 | 26 Feb 2013 | Class based views, staticfiles |

| 1.4 LTS[39] | 23 Mar 2012 | 26 Feb 2013 | 1 Oct 2015 | Time zones, in browser testing, app templates. |

| 1.5[40] | 26 Feb 2013 | 6 Nov 2013 | 2 Sep 2014 | Python 3 Support, configurable user model |

| 1.6[41] | 6 Nov 2013 | 2 Sep 2014 | 1 Apr 2015 | Dedicated to Malcolm Tredinnick, db transaction management, connection pooling. |

| 1.7[42] | 2 Sep 2014 | 1 Apr 2015 | 1 Dec 2015 | Migrations, application loading and configuration. |

| 1.8 LTS[43] | 1 Apr 2015 | 1 Dec 2015 | 1 Apr 2018 | Native support for multiple template engines. Support ended on 1 April 2018 |

| 1.9[44] | 1 Dec 2015 | 1 Aug 2016 | 4 Apr 2017 | Automatic password validation. New styling for admin interface. |

| 1.10[45] | 1 Aug 2016 | 4 Apr 2017 | 2 Dec 2017 | Full text search for PostgreSQL. New-style middleware. |

| 1.11 LTS[46] | 4 Apr 2017 | 2 Dec 2017 | 1 Apr 2020 | Last version to support Python 2.7. Support ended on 1 April 2020 |

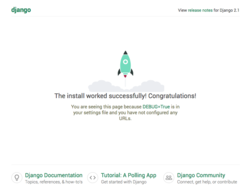

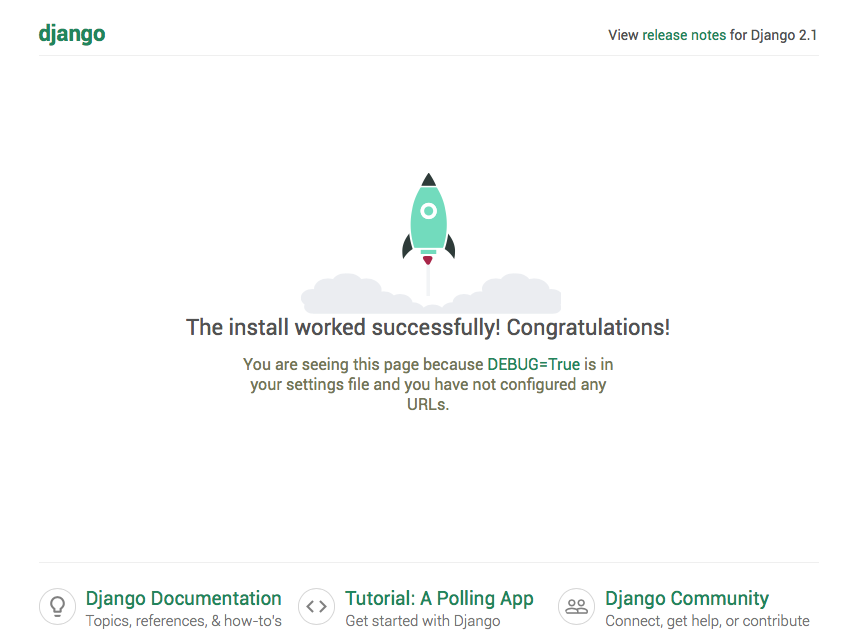

| 2.0[47] | 2 Dec 2017 | 1 Aug 2018 | 1 Apr 2019 | First Python 3-only release, Simplified URL routing syntax, Mobile friendly admin. |

| 2.1[48] | 1 Aug 2018 | 1 Apr 2019 | 2 Dec 2019 | Model "view" permission. |

| 2.2 LTS[49] | 1 Apr 2019 | 2 Dec 2019 | 11 Apr 2022 | Security release. |

| 3.0[50] | 2 Dec 2019 | 3 Aug 2020 | 6 Apr 2020 | ASGI support |

| 3.1[51] | 4 Aug 2020 | 6 Apr 2020 | 7 Dec 2021 | Asynchronous views and middleware |

| 3.2 LTS[52] | 6 Apr 2021 | 7 Dec 2021 | April 2024 | Tracking many to many relationships, added support for Python 3.11 |

| 4.0[53] | 7 Dec 2021 | 3 Aug 2022 | April 2023 | Support for pytz is now deprecated and will be removed in Django 5.0.

|

| 4.1[54] | 3 Aug 2022 | April 2023 | December 2023 | Asynchronous ORM interface, CSRF_COOKIE_MASKED setting, outputting a form, like {{ form }}

|

| 4.2 LTS[55] | 3 Apr 2023 | 4 Dec 2023 | Apr 2026 | Psycopg 3 support, ENGINE as django.db.backends.postgresql supports both libraries.

|

| 5.0[56] | 4 Dec 2023 | 7 Aug 2024 | 2 Apr 2025 | Facet filters in the admin, Simplified templates for form field rendering |

| 5.1[57] | 7 Aug 2024 | 2 Apr 2025 | Dec 2025 | Added support for Python 3.13. Added support for PostgreSQL connection pools. |

| 5.2 LTS[58] | 2 Apr 2025 | Dec 2025 | Apr 2028 | Automatic model import in shell, support for composite primary keys |

| 6.0[59][60] | 3 Dec 2025 | August 2026 | April 2027 | |

Unsupported Supported Latest version Preview version Future version | ||||

Community

[edit]DjangoCon

[edit]There is a semiannual conference for Django developers and users, named "DjangoCon", that has been held since September 2008. DjangoCon is held annually in Europe, in May or June;[61] while another is held in the United States in August or September, in various cities.[62]

United States

[edit]The 2012 DjangoCon took place in Washington, D.C., from September 3 to 8.

2013 DjangoCon was held in Chicago at the Hyatt Regency Hotel and the post-conference Sprints were hosted at Digital Bootcamp, computer training center.[63]

The 2014 DjangoCon US returned to Portland, OR from August 30 to 6 September.

The 2015 DjangoCon US was held in Austin, TX from September 6 to 11 at the AT&T Executive Center.

The 2016 DjangoCon US was held in Philadelphia, PA at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania from July 17 to 22.[64]

The 2017 DjangoCon US was held in Spokane, WA;[65] in 2018 DjangoCon US was held in San Diego, CA.[66] DjangoCon US 2019 was held again in San Diego, CA from September 22 to 27.

DjangoCon 2021 took place virtually and in 2022, DjangoCon US returned to San Diego from October 16 to 21. DjangoCon US 2023 was held from October 16 to 20 at the Durham, NC convention center and DjangoCon US 2024 took place also in Durham in September 22 to 27.[67][68]

DjangoCon US 2025 was held from September 8 to 12 in Chicago, Illinois.[69]

Europe

[edit]The 2025 edition of DjangoCon Europe took place in Dublin, Ireland from 23 to 27 April.[70]

In 2024, the conference was hosted in Vigo, Spain.[71]

Edinburgh, Scotland served as the venue for DjangoCon Europe in 2023.[72]

The 2022 conference was organized in Porto, Portugal.[73]

In 2021, DjangoCon Europe was held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[74]

The 2020 edition was also conducted as a fully virtual event.[75]

DjangoCon Europe 2019 was held in Copenhagen, Denmark.[76]

In 2018, the event took place in Heidelberg, Germany.[77]

The 2017 conference was convened in Florence, Italy.[78]

DjangoCon Europe 2012 was organized in Zurich, Switzerland.[79]

Australia

[edit]Django mini-conferences are usually held every year as part of the Australian Python Conference 'PyCon AU'.[80] Previously, these mini-conferences have been held in:

- Hobart, Australia, in July 2013,

- Brisbane, Australia, in August 2014 and 2015,

- Melbourne, Australia in August 2016 and 2017, and

- Sydney, Australia, in August 2018 and 2019.

Africa

[edit]The first DjangoCon Africa was held in Zanzibar, Tanzania, from 6 to 11 November 2023.[81] The event hosted approximately 200 attendees from 22 countries, including 103 women. The conference featured 26 talks on topics such as software development, education, careers, accessibility, and agriculture, often highlighting perspectives from across the African continent. Future editions of the conference are planned, with details available on the official website

Community groups & programs

[edit]Django has spawned user groups and meetups around the world, a notable group is the Django Girls organization, which began in Poland but now has had events in 91 countries.[82][83][84]

Another initiative is Djangonaut Space,[85] a mentorship program aimed at supporting new contributors to the Django ecosystem. The program pairs experienced mentors with developers to guide them through making meaningful contributions to Django and its community. It emphasizes long-term engagement, inclusion, and collaborative open-source development.

Ports to other languages

[edit]Programmers have ported Django's template engine design from Python to other languages, providing decent cross-platform support. Some of these options are more direct ports; others, though inspired by Django and retaining its concepts, take the liberty to deviate from Django's design:

CMSs based on Django Framework

[edit]Django as a framework is capable of building a complete CMS. Some dedicated CMS projects are based upon Django:

- Django CMS[92]

- Wagtail

- Mezzanine

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "django/README". GitHub. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Django FAQ". Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ "Release 6.0". 3 December 2025. Retrieved 3 December 2025.

- ^ "Release 5.2.9". 2 December 2025. Retrieved 3 December 2025.

- ^ "django/LICENSE". GitHub. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "FAQ: General - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ a b "FAQ: General - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ a b Adrian Holovaty, Jacob Kaplan-Moss; et al. The Django Book. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

Django follows this MVC pattern closely enough that it can be called an MVC framework

- ^ "Design Philosophies". Django. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "What Powers Instagram: Hundreds of Instances, Dozens of Technologies". Instagram Engineering.

- ^ "Python". Mozilla Developer Network. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Robenolt, Matt. "Scaling Django to 8 Billion Page Views". blog.disqus.com.

- ^ "DjangoSuccessStoryBitbucket – Django". Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "The anti-Facebook: one in four American neighborhoods are now using this private social network". The Verge. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Demi, Luke (15 August 2021). "Reining in the thundering herd ⛈ Getting to 80% CPU utilization with Django". Clubhouse Blog. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Willison, Simon. "What is the history of the Django web framework? Why has it been described as "developed in a newsroom"?". Quora. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Introducing Django". The Django Book. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "Review: Adrian Holovaty's Playful and Precise 'Melodic Guitar Music'". Acoustic Guitar. 12 December 2023. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Announcing the Django Software Foundation - Weblog - Django". 17 June 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Security in Django". Django Project. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Socol, James (2012). "Best Basic Security Practices (Especially with Django)". Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "What is a reusable app? — django-reusable-app-docs 0.1.0 documentation". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Django Packages API packages list". Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Design philosophies - Django documentation - Django". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Built-in template tags and filters". djangoproject. Retrieved 6 August 2025.

- ^ How to deploy Django. Official Django documentation.

- ^ "Django documentation". Django documentation. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Django's release process - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Download Django - Django". www.djangoproject.com.

- ^ "FAQ: Installation - Django documentation - Django". docs.djangoproject.com.

- ^ "Introducing Django 0.90". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 0.91 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Introducing Django 0.95". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Announcing Django 0.96!". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.0 released!". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.1 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.2 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.3 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.4 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.5 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.6 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ "Django 1.7 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Django 1.8 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "Django 1.9 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Django 1.10 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Django 1.11 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Django 2.0 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ "Django 2.1 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Django 2.2 release notes. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Django 3.0 release notes. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Django 3.1 release notes. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Django 3.2 release notes". 6 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Django 4.0 release notes". 7 December 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Django 4.1 release notes". 3 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Django 4.2 release notes". Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Django 5.0 release notes". 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Django 5.1 release notes". 7 August 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ "Django 5.2 release notes". 2 April 2025. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Django 6.0 Roadmap". December 2025. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Django 6.0 release notes". Django Project. 3 December 2025. Retrieved 3 December 2025.

- ^ DjangoCon EU series Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Lanyrd.com

- ^ DjangoCon US series Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Lanyrd.com

- ^ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon.

- ^ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon.

- ^ "About DjangoCon US 2023". DjangoCon US. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ "About DjangoCon US". DjangoCon US. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ US, DjangoCon (9 July 2025). "DjangoCon US 2025". DjangoCon US. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2025". 2025.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2024". 2024.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ Europe, DjangoCon. "DjangoCon EU 2023 • May 29th - June 2nd 2023 • Edinburgh, Scotland". DjangoCon Europe. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2022". 2022.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2021". 2021.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2020". 2020.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Join us in Copenhagen April 10-14th 🚲 • DjangoCon Europe 2019". 2019.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2018". 2018.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "DjangoCon Europe 2017 | Join us in Florence, April 3–7". 2017.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Home - 2012.djangocon.eu". 2012.djangocon.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ DjangoCon AU. Djangocon.com.au. Retrieved on 2019-12-16.

- ^ "DjangoCon Africa 2025". 2025.djangocon.africa. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Lawrence-born Django, which revolutionized website construction, celebrating its 10th anniversary". Lawrence Journal-World. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Django Girls - start your journey with programming". Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Django groups". Meetup.

- ^ "Djangonaut Space - Where contributors launch!". djangonaut.space. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ Shopify. "– Liquid template language". Liquid template language.

- ^ "Template::Swig - Perl interface to Django-inspired Swig templating engine. - metacpan.org". metacpan.org.

- ^ Symfony. "Home - Twig - The flexible, fast, and secure PHP template engine". twig.sensiolabs.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "twigjs/twig.js". GitHub.

- ^ "Welcome - Jinja2 (The Python Template Engine)". jinja.pocoo.org.

- ^ "erlydtl/erlydtl". GitHub.

- ^ "django CMS - Enterprise Content Management with Django - django CMS". www.django-cms.org. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jaiswal, Sanjeev; Kumar, Ratan (22 June 2015), Learning Django Web Development (1st ed.), Packt, p. 405, ISBN 978-1783984404

- Ravindrun, Arun (31 March 2015), Django Design Patterns and Best Practices (1st ed.), Packt, p. 180, ISBN 978-1783986644

- Osborn, Tracy (May 2015), Hello Web App (1st ed.), Tracy Osborn, p. 142, ISBN 978-0986365911

- Bendoraitis, Aidas (October 2014), Web Development with Django Cookbook (1st ed.), Packt, p. 294, ISBN 978-1783286898

- Baumgartner, Peter; Malet, Yann (2015), High Performance Django (1st ed.), Lincoln Loop, p. 184, ISBN 978-1508748120

- Elman, Julia; Lavin, Mark (2014), Lightweight Django (1st ed.), O'Reilly Media, p. 246, ISBN 978-1491945940

- Percival, Harry (2014), Test-Driven Development with Python (1st ed.), O'Reilly Media, p. 480, ISBN 978-1449364823, archived from the original on 16 July 2017, retrieved 26 October 2014

External links

[edit]Django (web framework)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and early development

Django was initially developed in the fall of 2003 by web programmers Adrian Holovaty and Simon Willison at the Lawrence Journal-World newspaper in Lawrence, Kansas, to facilitate content management for the organization's online news operations. The pair began using Python for building web applications after finding existing tools insufficient for their needs, starting with a classified ads system that required quick iterations to meet tight newsroom deadlines.[3] This focus on rapid prototyping led to the creation of reusable components, including an automatic admin interface for content editing and an object-relational mapping (ORM) system to simplify database interactions.[9] As internal usage expanded, Django powered multiple sites within the World Online network, such as LJWorld.com and KUSports.com, handling high traffic volumes.[9] By 2005, the framework managed two primary sites that collectively received millions of page hits daily, demonstrating its robustness for scalable news delivery. This growth underscored an emerging "batteries-included" approach, where core functionalities were bundled to accelerate development without sacrificing reliability.[3] Key early influences included Python's emphasis on simplicity and readability, which enabled fast coding, as well as prior tools like Webware for application serving and mod_python for Apache integration.[3] These elements shaped Django's foundation as a pragmatic framework tailored to the demands of deadline-driven journalism, evolving from ad-hoc scripts into a cohesive system before its eventual public release.[9]Public release and growth

Django was publicly released on July 21, 2005, under the three-clause BSD license, marking its transition from an internal tool to an open-source project available for widespread use.[10] This release aligned with the framework's origins at the Lawrence Journal-World and quickly attracted interest from developers seeking a robust solution for rapid web application development. By 2025, the project celebrated its 20th anniversary, highlighting its enduring impact on the Python ecosystem.[10] Early adoption was particularly strong among news organizations, with sites like the Washington Post integrating Django as early as December 2005 to power data-intensive applications such as the U.S. Congress Votes Database, which allowed users to explore legislative records dating back to 1991.[11] This uptake was driven by Django's ability to enable quick construction of complex, content-heavy web applications, reducing development time for dynamic sites handling high volumes of user-generated and editorial content. Similar news outlets recognized these strengths, contributing to the framework's initial momentum in media and publishing sectors. In June 2008, the Django Software Foundation (DSF) was established as a non-profit organization to manage the project's intellectual property, coordinate development efforts, and secure funding through sponsorships and grants.[12] The DSF's formation provided a structured governance model, ensuring sustainable growth while fostering community involvement in maintenance and enhancements. That same year, the inaugural DjangoCon conference took place in September at Google's Mountain View headquarters, gathering developers for sessions on best practices and emerging uses, which helped solidify the burgeoning community.[13] The framework's distribution was streamlined through its inclusion in the Python Package Index (PyPI), allowing developers to install and update Django easily via pip, which boosted accessibility and encouraged experimentation.[14] By 2010, adoption had expanded significantly, with high-profile platforms like Instagram and Pinterest leveraging Django for their core backends to handle rapid user growth and media-rich features.[15] Community contributions accelerated following the project's migration to GitHub in 2012, enabling more collaborative pull requests and issue tracking that propelled ongoing improvements.[16]Core Concepts

Design philosophy

Django's design philosophy centers on enabling rapid development of robust web applications while maintaining clean, pragmatic code. It is explicitly tailored for "perfectionists with deadlines," a principle that underscores the framework's commitment to delivering high-quality software efficiently under time constraints. This approach prioritizes developer productivity by handling common web development challenges out of the box, allowing focus on application logic rather than boilerplate infrastructure. A foundational tenet is the "Don't Repeat Yourself" (DRY) principle, which asserts that "every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system." By minimizing code duplication, DRY promotes efficiency, maintainability, and reduced errors across Django's architecture, from database interactions to templating. This philosophy encourages developers to define behaviors once and reuse them extensively, fostering a more modular codebase. Complementing DRY is the "batteries included" philosophy, which provides a comprehensive set of built-in tools and libraries for common tasks, such as an object-relational mapper (ORM), administrative interface, and authentication system. This full-stack approach eliminates the need to integrate third-party solutions for core functionalities, accelerating development while ensuring consistency and reliability. Django's developers aimed to create a framework where essential components are readily available, reducing setup time and promoting a standardized workflow. Loose coupling and reusability form another core aspect, designing components to operate independently with minimal interdependencies. This modularity allows for easy extension, testing, and replacement of parts without affecting the whole system, enhancing scalability and adaptability. For instance, apps can be developed and plugged in seamlessly, supporting reusable code that saves time and effort in larger projects. Security is prioritized from the ground up, with built-in protections against prevalent vulnerabilities integrated into the framework's core. Django automatically escapes template variables to prevent cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks, employs a query builder to mitigate SQL injection by escaping inputs, and uses middleware with token validation to guard against cross-site request forgery (CSRF). These measures, present since inception, reflect a proactive stance on secure-by-default development, helping developers build applications resistant to common threats without additional configuration.[17]Architectural pattern

Django follows the Model-Template-View (MTV) architectural pattern, a variant of the traditional Model-View-Controller (MVC) design used in web development.[18] In this structure, the Model layer handles data management and business logic, providing an abstraction over the database through Django's Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) system, which allows developers to define data structures in Python classes without writing raw SQL.[19] The View layer consists of Python functions or classes that receive HTTP requests, interact with models to retrieve or manipulate data, and determine the appropriate response.[20] The Template layer focuses on presentation, rendering dynamic HTML pages by combining static markup with data passed from views, enabling separation of logic from display concerns.[21] A key component of Django's architecture is the URL dispatcher, which maps incoming URLs to specific views using URL configuration modules (URLconfs). This system supports both regular expression-based patterns via there_path() function and simpler path converters via the path() function, allowing flexible routing that decouples URL structures from the underlying view code.[6]

The request-response cycle in Django begins with an incoming HTTP request, which passes through a middleware layer before reaching the URL dispatcher. The dispatcher routes the request to the appropriate view based on the URL pattern; the view then queries the model for necessary data and passes it to a template for rendering into an HTTP response, which travels back through middleware before being sent to the client.[22][23]

Django's middleware provides a lightweight plugin system for intercepting and modifying requests and responses globally, such as handling authentication via AuthenticationMiddleware or managing sessions with SessionMiddleware, without altering core application code.[23]

Unlike traditional MVC, where a separate Controller mediates between Model and View, Django's MTV assigns both controller-like request processing and view rendering responsibilities to the View component, emphasizing clear separation of concerns to enhance testability and maintainability.[18] This pattern supports extensibility through custom middleware implementations.[23]

Features

Core components

Django's core components form the foundational tools that enable developers to build robust web applications efficiently. The Object-Relational Mapper (ORM) serves as a central pillar, abstracting database interactions by allowing models to be defined as Python classes that correspond to database tables. Each model class includes fields defined as class attributes, such asCharField for text or IntegerField for numbers, which map directly to database columns. This abstraction enables database-agnostic operations, supporting multiple backends like PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQLite without altering the Python code. The ORM facilitates creating, retrieving, updating, and deleting objects through a high-level API, such as Model.objects.create() or Model.objects.filter().

A key feature of the ORM is its support for relationships between models, including foreign keys for one-to-many associations, many-to-many fields for complex links, and one-to-one for unique pairings. For instance, a ForeignKey field in a model class establishes a relationship to another model, automatically handling joins and integrity constraints in the underlying SQL. To manage schema evolution, Django's migration system tracks changes to models and generates SQL scripts to apply them incrementally. Developers use commands like python manage.py makemigrations to detect alterations and python manage.py migrate to execute them, ensuring safe, version-controlled database updates without manual SQL intervention.

The forms framework complements the ORM by handling user input validation and HTML form generation. Forms are defined as Python classes inheriting from forms.Form or forms.ModelForm, where fields mirror validation rules like required attributes or regex patterns. Upon submission, forms automatically validate data—rejecting invalid entries with error messages—and can render as HTML using methods like {{ form.as_p }} for paragraph-wrapped inputs. Model forms integrate seamlessly with the ORM by deriving fields from a specified model, enabling direct saving of validated data via form.save(), which creates or updates database instances.[24]

Django's admin interface provides an auto-generated, model-centric CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) dashboard, accessible via /admin/, that leverages the ORM to display and manage data. By registering models in admin.py, Django infers interfaces from model metadata, including list views, search, and filtering. Customization occurs through Python code, such as defining ModelAdmin subclasses to adjust fieldsets, permissions (e.g., via has_add_permission), and actions like bulk updates, all without frontend development.

The built-in authentication system manages user identity and access control, featuring a customizable User model with fields for username, email, and password hashing. It includes views for login (auth_login), logout (auth_logout), and password changes, plus middleware for session-based authentication. Permissions are handled through groups and object-level checks, allowing fine-grained control like restricting model access in the admin.

Internationalization (i18n) is supported out-of-the-box, enabling applications to handle multiple languages and locales. Developers mark translatable strings with gettext() or the {% trans %} template tag, after which Django extracts them into .po files for translation using tools like python manage.py makemessages. Locale-specific formatting for dates, numbers, and currencies is managed via LocaleMiddleware and settings like LANGUAGE_CODE, ensuring content adapts to user preferences.

Recent enhancements to the ORM include asynchronous query support introduced in Django 4.1 (August 2022), providing non-blocking methods like aget() and afilter() for QuerySets to improve performance in I/O-bound scenarios under ASGI servers. This was expanded in Django 5.0 (December 2023) and later versions with broader async compatibility for operations like aggregations and transactions, allowing seamless integration with async views while maintaining synchronous fallback options.

Bundled applications

Django includes a set of bundled applications within thedjango.contrib package, which provide out-of-the-box functionality for common web development tasks. These applications are optional but can be easily integrated by adding them to the INSTALLED_APPS setting in a project's configuration. They build upon Django's core components, such as models and views, to offer specialized features without requiring custom implementation.[25][26]

The django.contrib.auth application handles user authentication and authorization, including management of user accounts, groups, and permissions. It provides models like User for storing credentials with secure password hashing (defaulting to PBKDF2), Group for organizing users, and Permission for fine-grained access control. The system supports session-based login, where user sessions are maintained via cookies after successful authentication using the authenticate() and login() functions. This integration ensures secure, extensible user management across Django projects.[27][28]

Complementing authentication, the django.contrib.admin application delivers a ready-to-use administrative interface for model management. It automatically generates forms, lists, and editing views based on model metadata, accessible at the /admin/ URL. The admin site integrates tightly with django.contrib.auth by enforcing permissions—only authenticated users with appropriate rights can add, change, or delete records. Key features include customizable ModelAdmin classes for filters, search, and inline editing, making it suitable for rapid content administration.[29]

For maintaining user state, django.contrib.sessions offers a framework to store and retrieve arbitrary data per visitor on the server side. It abstracts session handling, sending session IDs via cookies to the client while supporting backends like database storage (default) or caching for performance. Sessions enable features such as keeping users logged in across requests without repeated authentication. This app is typically enabled via middleware and integrates with views for simple data persistence.[30]

The django.contrib.messages application provides a lightweight system for temporary notifications, allowing messages to be queued in one request and displayed in the next, often via templates. It supports levels like info, success, warning, and error, stored in sessions or cookies depending on configuration. This framework is commonly used for user feedback, such as form submission confirmations, and requires inclusion in middleware for operation.[31]

To enable generic relationships across models, django.contrib.contenttypes tracks all installed models via a ContentType registry, facilitating dynamic links without hardcoding specific model types. It introduces GenericForeignKey for referencing any model and supports reverse generic relations, useful for applications like tagging or comments that need to associate with varied content. This app depends on being listed in INSTALLED_APPS to populate its database table automatically.[32]

For multi-site deployments, django.contrib.sites introduces a Site model to associate content with specific domains or subdomains, enabling a single Django instance to serve multiple websites from shared databases. Configuration involves setting SITE_ID and populating site records, which can then be referenced in models or views for site-specific logic. This framework is essential for projects requiring domain-aware functionality.[33]

Asset management is handled by django.contrib.staticfiles, which collects CSS, JavaScript, and image files from applications into a designated directory for efficient serving. In development, it enables static file access during runserver; in production, the collectstatic command gathers files to STATIC_ROOT. Configuration options like STATICFILES_DIRS allow customization, ensuring seamless integration with Django's URL resolution.[34]

Content syndication is simplified through django.contrib.syndication, which generates RSS and Atom feeds from querysets or custom data. Developers create feed classes inheriting from Feed, defining items, titles, and links, then map them to URLs. This app supports dynamic feed generation, making it straightforward to expose updates like blog posts or news to feed readers.[35]

Finally, django.contrib.sitemaps automates XML sitemap creation to aid search engine optimization by listing URLs with metadata such as last modification dates and change frequencies. Sitemaps can be static, dynamic (from querysets), or indexed for large sites, and are integrated via URL patterns for automatic generation at endpoints like /sitemap.xml. This enhances site discoverability without manual maintenance.[36]

Extensibility mechanisms

Django's extensibility is facilitated through several mechanisms that allow developers to customize and extend its functionality without altering the core framework. These include modular applications, middleware, signals, custom template tags and filters, a robust third-party package ecosystem, configurable settings, and support for asynchronous operations. This design promotes reusability, decoupling, and integration, enabling developers to build complex applications efficiently.[37] Django applications, or "apps," serve as pluggable, modular units that encapsulate specific features, such as authentication or content management, making them reusable across projects. Developers can create custom apps using thestartapp management command and integrate them by adding their names to the INSTALLED_APPS list in the project's settings, which automatically registers models, views, and other components via Django's app registry. This structure supports extensibility by allowing seamless addition of functionality while maintaining loose coupling between modules.[25]

Middleware provides a lightweight plugin system for globally altering request and response processing, enabling custom logic to intercept and modify HTTP traffic at various stages. Custom middleware classes can define methods like process_request to handle incoming requests or process_response for outgoing responses, such as adding security headers or logging. This mechanism extends Django's core behavior across the entire application without requiring changes to individual views.[23]

Signals offer an event-driven architecture that decouples application components by allowing senders to notify receivers of specific actions, such as model changes, without direct dependencies. For instance, the built-in post_save signal can trigger custom handlers after a model instance is saved to the database, enabling tasks like sending notifications or updating caches. Developers connect receiver functions to signals using the connect method, fostering extensible, modular code that responds to framework events.[38]

The templating engine can be extended with custom tags and filters to incorporate reusable logic directly in templates, avoiding the need for complex view code. Custom tags, defined in a templatetags module within an app, handle dynamic operations like inclusion or iteration, while filters modify variable outputs, such as formatting dates. These are registered using Django's register class and made available after reloading the template loader, allowing developers to tailor the rendering process for domain-specific needs.[39]

Django's third-party package ecosystem enhances extensibility through easy integration of community-contributed libraries via the pip package manager. Packages are installed with pip install and typically added to INSTALLED_APPS, providing ready-made solutions for common requirements; for example, Django REST Framework (DRF) extends Django to build Web APIs with features like serialization, authentication, and browsable interfaces. The ecosystem, cataloged on sites like Django Packages, includes thousands of reusable apps and tools that integrate natively with Django's architecture.[40][41]

Settings configuration centralizes project customization in the settings.py module, where developers override Django's defaults for databases, templates, and middleware, among others. This Python-based file supports environment-specific adaptations, such as using different configurations for development versus production via multiple settings modules or environment variables, enabling flexible tweaks without code changes. It also facilitates third-party integrations by allowing custom settings namespaces.[42]

Since Django 3.1, released in August 2020, asynchronous support has been introduced through hooks for async views and middleware, allowing non-blocking operations in conjunction with ASGI servers like Daphne or Uvicorn. Developers can define async views using async def and implement async-compatible middleware methods, such as process_view or process_response, to integrate with async libraries for improved scalability in I/O-bound tasks. This extends Django's synchronous core to modern async patterns while maintaining backward compatibility.[43][44]

Deployment and scaling

Deploying Django applications in production requires configuring robust server environments to handle real-world traffic, security, and performance needs. Traditionally, Django uses the Web Server Gateway Interface (WSGI) for synchronous operations, with popular servers like Gunicorn and uWSGI providing efficient request handling. Gunicorn, a Python WSGI HTTP server, is widely recommended for its simplicity and ability to manage multiple worker processes, typically run with commands likegunicorn myproject.wsgi:application --workers=3. Similarly, uWSGI offers advanced features such as process management and can be configured via INI files for high-performance deployments. These servers are often paired with a reverse proxy like Nginx to manage static files and distribute load.

For asynchronous capabilities introduced in Django 3.0 and enhanced in version 5.x, the Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface (ASGI) enables support for WebSockets and async views. Daphne, Django's reference ASGI server, handles HTTP/2, HTTP/1.1, and WebSockets, installed via pip install daphne and run as daphne -b 0.0.0.0 -p 8000 myproject.asgi:application. Uvicorn, another high-performance ASGI server, is suitable for production with async features, invoked similarly with uvicorn myproject.asgi:application --host 0.0.0.0 --port 8000. These configurations allow Django to leverage modern Python async/await patterns for improved concurrency in I/O-bound applications.

Django officially supports several database backends, including PostgreSQL, MariaDB (as a MySQL-compatible alternative), MySQL, Oracle, and SQLite, with PostgreSQL recommended for production due to its robustness. Connection pooling was added in Django 5.1 (released August 2024) for PostgreSQL via the psycopg adapter, configurable in the database OPTIONS with a "pool" setting to manage connections efficiently and reduce overhead in high-traffic scenarios.

To enhance performance, Django's built-in cache framework supports multiple backends, including Memcached for distributed caching via libraries like python-memcached, configured in the CACHES setting as django.core.cache.backends.memcached.MemcachedCache. Redis integration is achieved through third-party packages like django-redis, enabling advanced features like pub/sub and persistence, with the backend set to django_redis.cache.RedisCache for scalable caching across multiple servers.

Django's stateless design, where each HTTP request is independent without server-side session storage by default, facilitates horizontal scaling by allowing easy replication of application instances behind a load balancer. Sessions and state can be offloaded to external stores like databases or Redis, enabling multiple servers to handle traffic interchangeably. For background tasks, Celery is commonly integrated as a distributed task queue, using Redis or RabbitMQ as brokers to process asynchronous jobs outside the main request-response cycle, configured by defining a Celery instance in Django's init.py and updating settings for broker URLs.

Security considerations in deployment include enforcing HTTPS via certificates (e.g., from Let's Encrypt) to protect data in transit, and setting the ALLOWED_HOSTS list in settings.py to specify permitted domains, preventing host header attacks. Static and media files should not be served by Django in production; instead, use Nginx for local serving or cloud storage providers like Amazon S3 for scalability, with Django's collectstatic command gathering files for deployment.

Common cloud integrations simplify scaling: Heroku provides a PaaS with built-in Django support, using a Procfile to specify Gunicorn commands and environment variables for configuration. AWS Elastic Beanstalk offers managed deployments with auto-scaling groups, supporting Django via platform hooks for database and static file setup. DigitalOcean's App Platform enables Git-based deployments with automatic builds, including Docker support for containerized environments. Containerization with Docker is prevalent, allowing Django apps to be packaged with dependencies in images, orchestrated via Docker Compose for local testing and deployed to clusters for production scaling.

Version History

Major releases

Django's major releases follow a time-based schedule, typically occurring every eight months, introducing new features, performance improvements, and backwards-incompatible changes while maintaining compatibility with supported Python versions. The first stable release, Django 1.0, arrived on September 3, 2008, marking the framework's transition from development to production readiness; it included a full admin interface for managing content, a robust Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) system for database interactions, and built-in testing tools to facilitate unit and integration testing.[45][46] Django 2.0, released on December 2, 2017, enhanced query efficiency with deferred field loading to avoid loading unnecessary data from the database and provided native PostgreSQL support enhancements, including better handling of JSON fields and full-text search capabilities.[47][48] Django 3.0, released on December 2, 2019, introduced support for the Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface (ASGI), enabling asynchronous views and better handling of concurrent requests, alongside a combined template loader that merges multiple backend loaders for simplified configuration and improved performance.[49][50] Django 4.0, launched on December 7, 2021, simplified URL patterns through expanded path converters and regex support in routing, while making the ORM async-aware to support non-blocking database operations in asynchronous contexts.[51][52] The April 3, 2023, release of Django 4.2 added support for using UUIDs as primary keys in models via the UUIDField with primary_key=True, promoting better scalability and anonymity in distributed systems without altering existing integer-based setups.[53][54] Django 5.0, released on December 4, 2023, brought asynchronous email support for non-blocking message sending in async views and introduced theif-split template tag for conditional rendering based on string splitting, aiding dynamic content generation.[55][56]

On August 7, 2024, Django 5.1 added official support for Python 3.13, ensuring compatibility with the latest language features, and implemented PostgreSQL connection pools to optimize database connection management and reduce overhead in high-traffic applications; this version receives support until December 2025.[57][58]

Django 5.2, issued on April 2, 2025, improved asynchronous views with better integration for async middleware and database queries, alongside critical security fixes addressing vulnerabilities in authentication and session handling. As of November 2025, the latest patch is 5.2.8, released November 5, 2025.[59][60][61]

The upcoming Django 6.0, scheduled for December 2025 and currently in beta as of November 2025, will feature enhancements such as support for Content Security Policy (CSP), background tasks, template partials, and improvements to the async ORM including window functions.[62][63]