Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Memory management

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2014) |

| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

Memory management (also dynamic memory management, dynamic storage allocation, or dynamic memory allocation) is a form of resource management applied to computer memory. The essential requirement of memory management is to provide ways to dynamically allocate portions of memory to programs at their request, and free it for reuse when no longer needed. This is critical to any advanced computer system where more than a single process might be underway (multitasking) at any time.[1]

Several methods have been devised that increase the effectiveness of memory management. Virtual memory systems separate the memory addresses used by a process from actual physical addresses, allowing separation of processes and increasing the size of the virtual address space beyond the available amount of RAM using paging or swapping to secondary storage. The quality of the virtual memory manager can have an extensive effect on overall system performance. The system allows a computer to appear as if it may have more memory available than physically present, thereby allowing multiple processes to share it.

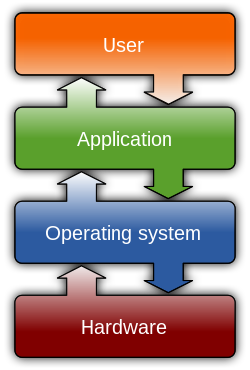

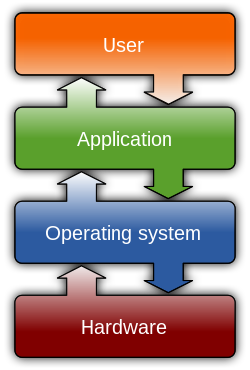

In some operating systems, e.g. Burroughs/Unisys MCP,[2] and OS/360 and successors,[3] memory is managed by the operating system.[note 1] In other operating systems, e.g. Unix-like operating systems, memory is managed at the application level.

Memory management within an address space is generally categorized as either manual memory management or automatic memory management.

Manual memory management

[edit]

The task of fulfilling an allocation request consists of locating a block of unused memory of sufficient size. Memory requests are satisfied by allocating portions from a large pool[note 2] of memory called the heap[note 3] or free store. At any given time, some parts of the heap are in use, while some are "free" (unused) and thus available for future allocations.

In the C language, the function which allocates memory from the heap is called malloc and the function which takes previously allocated memory and marks it as "free" (to be used by future allocations) is called free. [note 4]

Several issues complicate the implementation, such as external fragmentation, which arises when there are many small gaps between allocated memory blocks, which invalidates their use for an allocation request. The allocator's metadata can also inflate the size of (individually) small allocations. This is often managed by chunking. The memory management system must track outstanding allocations to ensure that they do not overlap and that no memory is ever "lost" (i.e. that there are no "memory leaks").

Efficiency

[edit]The specific dynamic memory allocation algorithm implemented can impact performance significantly. A study conducted in 1994 by Digital Equipment Corporation illustrates the overheads involved for a variety of allocators. The lowest average instruction path length required to allocate a single memory slot was 52 (as measured with an instruction level profiler on a variety of software).[1]

Implementations

[edit]Since the precise location of the allocation is not known in advance, the memory is accessed indirectly, usually through a pointer reference. The specific algorithm used to organize the memory area and allocate and deallocate chunks is interlinked with the kernel, and may use any of the following methods:

Fixed-size blocks allocation

[edit]Fixed-size blocks allocation, also called memory pool allocation, uses a free list of fixed-size blocks of memory (often all of the same size). This works well for simple embedded systems where no large objects need to be allocated but suffers from fragmentation especially with long memory addresses. However, due to the significantly reduced overhead, this method can substantially improve performance for objects that need frequent allocation and deallocation, and so it is often used in video games.

Buddy blocks

[edit]In this system, memory is allocated into several pools of memory instead of just one, where each pool represents blocks of memory of a certain power of two in size, or blocks of some other convenient size progression. All blocks of a particular size are kept in a sorted linked list or tree and all new blocks that are formed during allocation are added to their respective memory pools for later use. If a smaller size is requested than is available, the smallest available size is selected and split. One of the resulting parts is selected, and the process repeats until the request is complete. When a block is allocated, the allocator will start with the smallest sufficiently large block to avoid needlessly breaking blocks. When a block is freed, it is compared to its buddy. If they are both free, they are combined and placed in the correspondingly larger-sized buddy-block list.

Slab allocation

[edit]This memory allocation mechanism preallocates memory chunks suitable to fit objects of a certain type or size.[5] These chunks are called caches and the allocator only has to keep track of a list of free cache slots. Constructing an object will use any one of the free cache slots and destructing an object will add a slot back to the free cache slot list. This technique alleviates memory fragmentation and is efficient as there is no need to search for a suitable portion of memory, as any open slot will suffice.

Stack allocation

[edit]Many Unix-like systems as well as Microsoft Windows implement a function called alloca for dynamically allocating stack memory in a way similar to the heap-based malloc. A compiler typically translates it to inlined instructions manipulating the stack pointer.[6] Although there is no need of manually freeing memory allocated this way as it is automatically freed when the function that called alloca returns, there exists a risk of overflow. And since alloca is an ad hoc expansion seen in many systems but never in POSIX or the C standard, its behavior in case of a stack overflow is undefined.

A safer version of alloca called _malloca, which reports errors, exists on Microsoft Windows. It requires the use of _freea.[7] gnulib provides an equivalent interface, albeit instead of throwing an SEH exception on overflow, it delegates to malloc when an overlarge size is detected.[8] A similar feature can be emulated using manual accounting and size-checking, such as in the uses of alloca_account in glibc.[9]

Automated memory management

[edit]The proper management of memory in an application is a difficult problem, and several different strategies for handling memory management have been devised.

Automatic management of call stack variables

[edit]In many programming language implementations, the runtime environment for the program automatically allocates memory in the call stack for non-static local variables of a subroutine, called automatic variables, when the subroutine is called, and automatically releases that memory when the subroutine is exited. Special declarations may allow local variables to retain values between invocations of the procedure, or may allow local variables to be accessed by other subroutines. The automatic allocation of local variables makes recursion possible, to a depth limited by available memory.

Garbage collection

[edit]Garbage collection is a strategy for automatically detecting memory allocated to objects that are no longer usable in a program, and returning that allocated memory to a pool of free memory locations. This method is in contrast to "manual" memory management where a programmer explicitly codes memory requests and memory releases in the program. While automatic garbage collection has the advantages of reducing programmer workload and preventing certain kinds of memory allocation bugs, garbage collection does require memory resources of its own, and can compete with the application program for processor time.

Reference counting

[edit]Reference counting is a strategy for detecting that memory is no longer usable by a program by maintaining a counter for how many independent pointers point to the memory. Whenever a new pointer points to a piece of memory, the programmer is supposed to increase the counter. When the pointer changes where it points, or when the pointer is no longer pointing to any area or has itself been freed, the counter should decrease. When the counter drops to zero, the memory should be considered unused and freed. Some reference counting systems require programmer involvement and some are implemented automatically by the compiler. A disadvantage of reference counting is that circular references can develop which cause a memory leak to occur. This can be mitigated by either adding the concept of a "weak reference" (a reference that does not participate in reference counting, but is notified when the area it is pointing to is no longer valid) or by combining reference counting and garbage collection together.

Memory pools

[edit]A memory pool is a technique of automatically deallocating memory based on the state of the application, such as the lifecycle of a request or transaction. The idea is that many applications execute large chunks of code which may generate memory allocations, but that there is a point in execution where all of those chunks are known to be no longer valid. For example, in a web service, after each request the web service no longer needs any of the memory allocated during the execution of the request. Therefore, rather than keeping track of whether or not memory is currently being referenced, the memory is allocated according to the request or lifecycle stage with which it is associated. When that request or stage has passed, all associated memory is deallocated simultaneously.

Systems with virtual memory

[edit]Virtual memory is a method of decoupling the memory organization from the physical hardware. The applications operate on memory via virtual addresses. Each attempt by the application to access a particular virtual memory address results in the virtual memory address being translated to an actual physical address.[10] In this way the addition of virtual memory enables granular control over memory systems and methods of access.

In virtual memory systems the operating system limits how a process can access the memory. This feature, called memory protection, can be used to disallow a process to read or write to memory that is not allocated to it, preventing malicious or malfunctioning code in one program from interfering with the operation of another.

Even though the memory allocated for specific processes is normally isolated, processes sometimes need to be able to share information. Shared memory is one of the fastest techniques for inter-process communication.

Memory is usually classified by access rate into primary storage and secondary storage. Memory management systems, among other operations, also handle the moving of information between these two levels of memory.

An operating system manages various resources in the computing system. The memory subsystem is the system element for managing memory. The memory subsystem combines the hardware memory resource and the MCP OS software that manages the resource.

The memory subsystem manages the physical memory and the virtual memory of the system (both part of the hardware resource). The virtual memory extends physical memory by using extra space on a peripheral device, usually disk. The memory subsystem is responsible for moving code and data between main and virtual memory in a process known as overlaying. Burroughs was the first commercial implementation of virtual memory (although developed at Manchester University for the Ferranti Atlas computer) and integrated virtual memory with the system design of the B5000 from the start (in 1961) needing no external memory management unit (MMU).[11]: 48

The memory subsystem is responsible for mapping logical requests for memory blocks to physical portions of memory (segments) which are found in the list of free segments. Each allocated block is managed by means of a segment descriptor,[12] a special control word containing relevant metadata about the segment including address, length, machine type, and the p-bit or ‘presence’ bit which indicates whether the block is in main memory or needs to be loaded from the address given in the descriptor.

Descriptors are essential in providing memory safety and security so that operations cannot overflow or underflow the referenced block (commonly known as buffer overflow). Descriptors themselves are protected control words that cannot be manipulated except for specific elements of the MCP OS (enabled by the UNSAFE block directive in NEWP).

Donald Knuth describes a similar system in Section 2.5 ‘Dynamic Storage Allocation’ of ‘Fundamental Algorithms’.[disputed – discuss]

Memory management in OS/360 and successors

[edit]IBM System/360 does not support virtual memory.[note 5] Memory isolation of jobs is optionally accomplished using protection keys, assigning storage for each job a different key, 0 for the supervisor or 1–15. Memory management in OS/360 is a supervisor function. Storage is requested using the GETMAIN macro and freed using the FREEMAIN macro, which result in a call to the supervisor (SVC) to perform the operation.

In OS/360 the details vary depending on how the system is generated, e.g., for PCP, MFT, MVT.

In OS/360 MVT, suballocation within a job's region or the shared System Queue Area (SQA) is based on subpools, areas a multiple of 2 KB in size—the size of an area protected by a protection key. Subpools are numbered 0–255.[13] Within a region subpools are assigned either the job's storage protection or the supervisor's key, key 0. Subpools 0–127 receive the job's key. Initially only subpool zero is created, and all user storage requests are satisfied from subpool 0, unless another is specified in the memory request. Subpools 250–255 are created by memory requests by the supervisor on behalf of the job. Most of these are assigned key 0, although a few get the key of the job. Subpool numbers are also relevant in MFT, although the details are much simpler.[14] MFT uses fixed partitions redefinable by the operator instead of dynamic regions and PCP has only a single partition.

Each subpool is mapped by a list of control blocks identifying allocated and free memory blocks within the subpool. Memory is allocated by finding a free area of sufficient size, or by allocating additional blocks in the subpool, up to the region size of the job. It is possible to free all or part of an allocated memory area.[15]

The details for OS/VS1 are similar[16] to those for MFT and for MVT; the details for OS/VS2 are similar to those for MVT, except that the page size is 4 KiB. For both OS/VS1 and OS/VS2 the shared System Queue Area (SQA) is nonpageable.

In MVS the address space[17] includes an additional pageable shared area, the Common Storage Area (CSA), and two additional private areas, the nonpageable local system queue area (LSQA) and the pageable System Work area (SWA). Also, the storage keys 0–7 are all reserved for use by privileged code.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ However, the run-time environment for a language processor may subdivide the memory dynamically acquired from the operating system, e.g., to implement a stack.

- ^ In some operating systems, e.g., OS/360, the free storage may be subdivided in various ways, e.g., subpools in OS/360, below the line, above the line and above the bar in z/OS.

- ^ Not to be confused with the unrelated heap data structure.

- ^ A simplistic implementation of these two functions can be found in the article "Inside Memory Management".[4]

- ^ Except on the Model 67

References

[edit]- ^ a b Detlefs, D.; Dosser, A.; Zorn, B. (June 1994). "Memory allocation costs in large C and C++ programs" (PDF). Software: Practice and Experience. 24 (6): 527–542. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.30.3073. doi:10.1002/spe.4380240602. S2CID 14214110.

- ^ a b "Unisys MCP Managing Memory". System Operations Guid. Unisys.

- ^ "Main Storage Allocation" (PDF). IBM Operating System/360 Concepts and Facilities (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library (First ed.). IBM Corporation. 1965. p. 74. Retrieved Apr 3, 2019.

- ^ Jonathan Bartlett. "Inside Memory Management". IBM DeveloperWorks.

- ^ Silberschatz, Abraham; Galvin, Peter B. (2004). Operating system concepts. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-69466-5.

- ^ – Linux Programmer's Manual – Library Functions from Manned.org

- ^ "_malloca". Microsoft CRT Documentation. 26 October 2022.

- ^ "gnulib/malloca.h". GitHub. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "glibc/include/alloca.h". Beren Minor's Mirrors. 23 November 2019.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1992). Modern Operating Systems. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 90. ISBN 0-13-588187-0.

- ^ Waychoff, Richard. "Stories About the B5000 and People Who Were There" (PDF). Computer History Museum.

- ^ The Descriptor (PDF). Burroughs Corporation. February 1961.

- ^ OS360Sup, pp. 82–85.

- ^ OS360Sup, pp. 82.

- ^ Program Logic: IBM System/360 Operating System MVT Supervisor (PDF). IBM Corporation. May 1973. pp. 107–137. Retrieved Apr 3, 2019.

- ^ OSVS1Dig, p. 2.37-2.39.

- ^ "Virtual Storage Layout" (PDF). Introduction to OS/VS2 Release 2 (PDF). Systems (first ed.). IBM. March 1973. p. 37. GC28-0661-1. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Donald Knuth. Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.5: Dynamic Storage Allocation, pp. 435–456.

- Simple Memory Allocation AlgorithmsArchived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (originally published on OSDEV Community)

- Wilson, P. R.; Johnstone, M. S.; Neely, M.; Boles, D. (1995). "Dynamic storage allocation: A survey and critical review" (PDF). Memory Management. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 986. pp. 1–116. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.47.275. doi:10.1007/3-540-60368-9_19. ISBN 978-3-540-60368-9.

- Berger, E. D.; Zorn, B. G.; McKinley, K. S. (June 2001). "Composing High-Performance Memory Allocators" (PDF). Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 2001 conference on Programming language design and implementation. PLDI '01. pp. 114–124. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1.2112. doi:10.1145/378795.378821. ISBN 1-58113-414-2. S2CID 7501376.

- Berger, E. D.; Zorn, B. G.; McKinley, K. S. (November 2002). "Reconsidering Custom Memory Allocation" (PDF). Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN conference on Object-oriented programming, systems, languages, and applications. OOPSLA '02. pp. 1–12. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.5298. doi:10.1145/582419.582421. ISBN 1-58113-471-1. S2CID 481812.

- OS360Sup

- OS Release 21 IBM System/360 Operating System Supervisor Services and Macro Instructions (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library (Eighth ed.). IBM. September 1974. GC28-6646-7.

- OSVS1Dig

- OS/VS1 Programmer's Reference Digest Release 6 (PDF). Systems (Sixth ed.). IBM. September 15, 1976. GC24-5091-5 with TNLs.

External links

[edit]Memory management

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

Memory management refers to the collection of techniques employed by operating systems to allocate, deallocate, and monitor the memory resources utilized by running programs and system processes.[3] This process ensures that multiple programs can coexist in memory without interfering with one another, by mapping logical addresses generated by programs to physical addresses in hardware.[5] The primary purpose of memory management is to optimize the utilization of finite memory resources, thereby enhancing overall system performance and reliability.[3] It aims to prevent issues such as memory leaks—where allocated memory is not properly released—external and internal fragmentation, which scatters free memory into unusable fragments, and access violations that could lead to crashes or security breaches.[9] Key objectives include maximizing computational throughput by keeping the CPU utilized, minimizing access latency through efficient allocation, and enabling multitasking by isolating processes in protected address spaces.[3][10] In the early days of computing during the 1950s, memory management was largely absent, requiring programmers to manually oversee memory usage on machines with limited RAM, often leading to inefficient and error-prone code. Formal memory management began to emerge in the late 1950s and 1960s with the development of early multiprogramming systems, such as the Atlas computer (1962),[11] and operating systems like Multics (1965), which introduced advanced structured allocation and protection mechanisms to support multiple users and processes simultaneously.[12] Central challenges in memory management encompass providing robust protection to prevent unauthorized access between processes, facilitating safe memory sharing for efficient communication, and abstracting physical memory constraints to offer programs a uniform, larger address space—often through techniques like virtual memory.[13][10][14]Memory Hierarchy and Models

The memory hierarchy in computer architecture refers to the structured organization of storage systems in a computer, ranging from the fastest and smallest components closest to the processor to slower and larger ones further away. At the top level are processor registers, which provide the quickest access times, typically in the range of 0.5 to 1 nanosecond, but with very limited capacity of a few kilobytes.[15] Following registers are cache memories, divided into levels such as L1 (split into instruction and data caches, with capacities around 32-64 KB and access times of 1-4 nanoseconds), L2 (256 KB to a few MB, 5-10 nanoseconds), and L3 (several MB to tens of MB, 10-30 nanoseconds), shared among processor cores.[16] Main memory, or RAM, offers capacities from gigabytes to terabytes with access times of 50-100 nanoseconds, serving as the primary working storage.[15] At the bottom are secondary storage devices like solid-state drives (SSDs) and hard disk drives (HDDs), providing terabytes to petabytes of capacity but with access times in the microseconds (SSDs) to milliseconds (HDDs) range.[16] This hierarchy balances trade-offs in speed, capacity, and cost: upper levels are faster and more expensive per bit (e.g., registers cost thousands of dollars per megabyte), while lower levels are slower but cheaper (e.g., HDDs at cents per gigabyte) and larger in scale.[15] The design exploits the principle that not all data needs instantaneous access, allowing systems to approximate an ideal memory that is simultaneously fast, capacious, and inexpensive—properties that no single technology can fully achieve in reality.[15] As a result, data is automatically migrated between levels based on usage, minimizing overall access latency while maximizing effective throughput. Access patterns in programs exhibit temporal locality, where recently accessed data is likely to be referenced again soon, and spatial locality, where data near a recently accessed location is likely to be accessed next.[17] These principles, first formalized in the context of virtual memory systems, justify the use of caching: by storing frequently or proximally used data in faster upper levels, the hierarchy reduces average access times for typical workloads like loops or sequential scans.[18] For instance, in matrix multiplication algorithms, spatial locality in row-major storage allows prefetching adjacent elements into cache, improving performance without explicit programmer intervention.[17] The memory hierarchy is fundamentally shaped by the von Neumann architecture, which stores both instructions and data in the same memory address space, accessed via a shared bus between the processor and memory.[19] This design, outlined in John von Neumann's 1945 report on the EDVAC computer, creates the von Neumann bottleneck: the bus's limited bandwidth constrains data transfer rates, even as processor speeds increase, leading to underutilized computation cycles while waiting for memory fetches.[20] Modern systems mitigate this through multilevel caching and pipelining, but the bottleneck persists as a key limitation in scaling performance.[21] Performance in the memory hierarchy is evaluated using metrics like hit rate (the fraction of accesses served by a cache level) and miss rate (1 minus hit rate), which quantify how effectively locality is exploited.[15] The average memory access time (AMAT) for a given level combines these with the time to service hits and the additional penalty for misses, as expressed in the formula: Here, hit time is the latency for a successful cache access, and miss penalty includes the time to fetch from a lower level.[15] For example, if an L1 cache has a 95% hit rate, 1 ns hit time, and 50 ns miss penalty, the AMAT is approximately 4.75 ns, highlighting how even small miss rates amplify effective latency. These metrics guide optimizations, such as increasing cache associativity to boost hit rates in workloads with irregular access patterns.[15]Hardware Foundations

Physical Memory Organization

Physical memory in modern computer systems is primarily implemented using Dynamic Random-Access Memory (DRAM), where the fundamental storage unit is the DRAM cell. Each DRAM cell consists of a single transistor and a capacitor, capable of storing one bit of data by charging or discharging the capacitor; the transistor acts as a switch to access the capacitor during read or write operations.[22] These cells are arranged in a two-dimensional array within a DRAM bank, organized into rows (wordlines) and columns (bitlines), allowing parallel access to data along a row when activated.[23] A typical DRAM device contains multiple banks—ranging from 4 to 32 per chip, as in DDR5 SDRAM—to enable concurrent operations and improve throughput by interleaving accesses across banks.[22][24] Memory modules package these DRAM chips into standardized form factors for easier installation and scalability in systems. Single In-line Memory Modules (SIMMs), introduced in the 1980s, feature pins on one side of the module and support 8-bit or 32-bit data paths, with 30-pin or 72-pin variants commonly used in early personal computers for capacities up to several megabytes. Dual In-line Memory Modules (DIMMs), developed in the 1990s as an evolution of SIMMs, have pins on both sides for independent signaling, enabling 64-bit data paths and higher densities; they became the standard for desktop and server systems, supporting synchronous DRAM (SDRAM) and later generations like DDR. These modules are typically organized into ranks and channels within the system, where a rank comprises multiple DRAM chips operating in unison to form a wider data word. The organization of physical memory can be byte-addressable or word-addressable, determining the granularity of access. In byte-addressable memory, each individual byte (8 bits) has a unique address, allowing fine-grained access suitable for modern processors handling variable-length data; this is the dominant scheme in contemporary systems for flexibility in programming.[25] Word-addressable memory, conversely, assigns addresses to fixed-size words (e.g., 32 or 64 bits), which simplifies hardware but limits access to multiples of the word size and is less common today except in specialized embedded systems.[25] The Memory Management Unit (MMU) plays a key role in translating logical addresses to these physical locations, decoding them into components like bank, row, and column indices for accurate access.[26] Hardware mechanisms for protection ensure isolation and prevent unauthorized access to physical memory regions. Base and limit registers provide a simple form of protection: the base register holds the starting physical address of a process's memory allocation, while the limit register specifies the size of that allocation; hardware compares each generated address against these to enforce bounds, trapping violations as faults.[27] For advanced isolation, tagged memory architectures attach metadata tags (e.g., 4-16 bits per word or granule) to memory locations, enabling hardware enforcement of access policies based on tag matching between pointers and data; this supports fine-grained security without relying solely on segmentation or paging.[28] Such systems, like those proposed in RISC-V extensions, detect spatial and temporal safety violations at runtime with minimal overhead.[28] Error handling in physical memory relies on techniques to detect and correct faults arising from cosmic rays, manufacturing defects, or wear. Parity bits offer basic single-bit error detection by adding an extra bit to each byte or word, set to make the total number of 1s even (even parity) or odd; during reads, the hardware recalculates parity to flag mismatches, though it cannot correct errors.[29] Error-Correcting Code (ECC) mechanisms extend this by using more sophisticated codes, such as Hamming or Reed-Solomon, to detect and correct single-bit errors (SEC) and detect double-bit errors (DED); in DRAM, ECC is often implemented across multiple chips in a module, adding 8-12.5% overhead for server-grade reliability.[30] Modern on-die ECC in DRAM chips applies single-error correction directly within the device, reducing latency compared to system-level correction.[31]Addressing and Access Mechanisms

Addressing modes in computer architectures specify how the effective memory address of an operand is calculated using information from the instruction, registers, and constants. Absolute or direct addressing embeds the full address directly in the instruction, requiring a separate word for the address in fixed-length instruction sets like MIPS. Relative addressing, often PC-relative, computes the address by adding a signed offset to the program counter, commonly used in branch instructions to support position-independent code. Indirect addressing retrieves the operand address from a register or memory location pointed to by the instruction, enabling pointer-based access as in the MIPS load instructionlw $8, ($9). Indexed or base-displacement addressing forms the address by adding a register's contents to a small constant offset, facilitating array and structure access, such as lw $8, 24($9) in MIPS. These modes reduce instruction encoding overhead and enhance flexibility, with load/store architectures like MIPS limiting modes to simplify design while memory-to-memory architectures offer more variety.[32]

In the x86 architecture, addressing modes build on these concepts with extensive support for combinations like register indirect, where the effective address is the contents of a register, and memory indirect, restricted primarily to control transfers such as CALL [func1] or JMP [func2], where a memory location holds the target address. x86 avoids cascaded indirect addressing to limit complexity, but register indirect provides efficient large-address-space access with one fewer memory reference than full memory indirect. These modes in x86 enable compact encoding for variables, arrays, and pointers, balancing performance and instruction size in complex data structures.[33]

Hardware facilitates memory access through a structured bus system comprising the address bus, which unidirectional signals specify the target memory location for reads or writes; the data bus, which bidirectional transfers the operand data between processor and memory; and the control bus, which conveys timing and operation signals like read/write enables to synchronize transfers. These buses form the front-side bus or system bus, enabling parallel address specification and data movement to match processor word sizes, such as 32 or 64 bits.[34]

For peripherals requiring high-throughput data transfer, Direct Memory Access (DMA) allows hardware controllers to bypass the CPU, directly reading from or writing to main memory via the system bus. In DMA, the CPU initializes the controller by loading source/destination addresses and transfer counts into dedicated registers, after which the DMA seizes bus control, increments addresses autonomously, and signals completion via interrupt, freeing the CPU for other tasks. This mechanism significantly boosts efficiency by reducing CPU overhead during data transfers, such as in disk-to-memory operations, and improving overall system throughput.

To mitigate latency in repeated memory accesses, caching employs set-associative mapping, organizing cache lines into sets where each memory block maps to one set but can reside in any of multiple lines within it, such as 8-way sets in L1 caches (32 KB, 64 sets, 64-byte lines) or 24-way in L2 (6 MB, 4096 sets). This approach compromises between direct-mapped speed and fully associative hit rates, using policies like LRU for line replacement on conflicts. Eviction in set-associative caches handles dirty lines based on write policies to maintain consistency.[35]

Cache write policies contrast in handling stores: write-through immediately propagates updates to both cache and main memory, ensuring consistency for I/O or multiprocessor systems but incurring higher bandwidth and potential stalls due to slower memory writes. Write-back, conversely, modifies only the cache line—marked dirty via a dedicated bit—and defers memory updates until eviction, minimizing traffic since multiple writes to the same line require just one eventual write-back, though it demands coherency protocols in multi-core environments. Write-back typically outperforms write-through by leveraging write buffers to hide eviction costs, reducing inter-level bandwidth by consolidating updates.[35][36]

Prefetching complements these mechanisms by proactively loading anticipated data into cache, exploiting spatial locality through techniques like larger block sizes that fetch adjacent words on misses, thereby reducing cold misses and compulsory faults in sequential access patterns.[35]

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) acts as a specialized hardware cache in the memory management unit, storing recent virtual-to-physical address mappings to accelerate translations in paged systems. On access, the MMU queries the TLB: a hit delivers the physical address in minimal cycles without page table intervention, while a miss triggers a memory-based table walk to resolve and cache the entry. TLBs leverage temporal and spatial locality for hit rates often exceeding 70% in workloads like array traversals, drastically cutting the overhead of multi-level page table accesses that would otherwise double memory latency.[37]

In implementations like ARM, the TLB hierarchy includes small micro-TLBs (e.g., 8 entries each for instructions and data) for hit-free fast paths, supported by a larger main TLB (typically 64 entries) that caches translations with attributes like permissions and memory types, using opaque replacement policies to prioritize recency. This structure ensures virtual memory's practicality by confining translation costs to rare misses.[38]

Operating System Strategies

Virtual Memory Concepts

Virtual memory is a fundamental abstraction in operating systems that provides each process with the illusion of possessing a large, dedicated, and contiguous block of memory, regardless of the actual physical memory available. This is achieved by mapping a process's logical address space—generated by the program—onto the physical address space of the machine through an automatic translation mechanism, such as an address map. As described in early systems like Multics, this separation allows processes to operate as if they have exclusive access to a vast memory region, while the operating system manages the underlying physical constraints by relocating data between main memory and secondary storage.[39][40] A key technique enabling this illusion is demand paging, where pages of a program's virtual address space are loaded into physical memory only upon reference, rather than preloading the entire program. This on-demand loading, combined with swapping—transferring entire working sets or pages to and from disk—allows systems to support programs larger than physical memory and facilitates efficient use of resources. When a process references a page not currently in memory, a page fault occurs, triggering the operating system's handler to retrieve the page from disk, update the address mapping, and resume execution; this process ensures transparency to the application while incurring a performance overhead for disk I/O.[39][40] The benefits of virtual memory include enhanced process isolation, as each process's address space is protected from others through access controls and separate mappings, preventing unauthorized interference and improving system stability. It also enables efficient multitasking by allowing multiple processes to share physical memory without mutual awareness, thus supporting higher degrees of multiprogramming. Furthermore, it simplifies programming by freeing developers from managing physical addresses or memory overlays, allowing them to focus on logical structures and assume abundant contiguous space.[39][40] However, virtual memory can lead to thrashing, a performance degradation where the system spends excessive time on paging operations due to overcommitted memory, resulting in frequent page faults and low CPU utilization as processes wait for disk transfers. To mitigate thrashing, the working set model, which defines a process's working set as the set of pages referenced within a recent time window (e.g., the last τ seconds of execution), ensures that memory allocation keeps the aggregate working set sizes within physical limits, thereby minimizing faults and maintaining throughput. This approach resists thrashing by dynamically monitoring locality of reference and suspending processes whose working sets exceed available frames.[39][41]Paging Techniques

Paging divides both virtual and physical memory into fixed-size blocks known as pages and frames, respectively, allowing the operating system to map virtual pages to physical frames through a page table data structure. This approach eliminates external fragmentation and simplifies allocation by treating memory as a collection of equal-sized units. The concept originated in the Atlas computer, where pages were fixed at 512 words to enable efficient virtual storage management across a one-million-word address space using drums for secondary storage. Modern systems commonly use page sizes of 4 KB for balancing translation overhead and transfer efficiency. A page table is an array of entries, each containing the physical frame number for a corresponding virtual page, along with protection bits and validity flags to indicate if the page is present in memory. When a process references a virtual address, the memory management unit (MMU) uses the page table to translate it to a physical address; if the page is not resident, a page fault occurs, triggering the operating system to load it from disk. To address the space inefficiency of a single-level page table for large virtual address spaces—such as allocating entries for unused pages—multi-level page tables employ a hierarchical structure where higher-level directories point to lower-level tables, allocating only sub-tables for active address regions. For instance, Multics implemented a multi-level paging scheme integrated with segmentation to support sparse address spaces in its virtual memory system. Similarly, the Intel 80386 introduced a two-level paging mechanism, with a page directory indexing up to 1,024 page tables, each handling 4 MB of virtual memory to extend addressing beyond 16 MB while minimizing wasted table space. In demand paging, a core implementation of paging within virtual memory, pages are not preloaded into physical memory; instead, they are brought in on demand only when accessed, reducing initial load times and allowing processes to start with minimal resident pages. This technique, pioneered in the Atlas system, relies on page faults to trigger transfers from secondary storage, with the operating system maintaining a free frame list or using replacement policies when frames are scarce. Copy-on-write (COW) enhances demand paging during process creation, such as in forking, by initially sharing physical pages between parent and child processes marked as read-only; a write to a shared page causes a fault that allocates a new frame, copies the content, and updates the page tables for both processes. Introduced in UNIX systems like 4.2BSD, COW significantly reduces fork overhead— for example, cutting response times by avoiding full copies when children modify less than 50% of memory, as seen in applications like Franz Lisp (23% writes) and GNU Emacs (35% writes)—while also conserving swap space and minimizing paging activity. Page replacement algorithms determine which resident page to evict when a page fault requires a free frame and none are available, aiming to minimize fault rates under locality of reference assumptions. The First-In-First-Out (FIFO) algorithm replaces the oldest page in memory, implemented via a simple queue, but it can exhibit Belady's anomaly where increasing frame count paradoxically increases faults for certain reference strings. Belady's anomaly, observed in FIFO on systems like the IBM M44/44X, occurs because larger frames allow distant future references to delay evictions of soon-needed pages; for a reference string like 1,2,3,4,1,2,5,1,2,3,4,5, FIFO yields 9 faults with 3 frames but 10 with 4. The Optimal (OPT) algorithm, theoretically ideal, replaces the page whose next reference is farthest in the future, achieving the minimum possible faults but requiring future knowledge, making it unusable online though useful for simulations. The Least Recently Used (LRU) algorithm approximates OPT by evicting the page unused for the longest past time, leveraging temporal locality; it avoids Belady's anomaly and performs near-optimally, often implemented approximately using hardware reference bits in page table entries to track usage without full timestamps.Segmentation Methods

Segmentation divides a process's virtual memory into variable-sized partitions called segments, each corresponding to a logical unit of the program such as the code segment, data segment, or stack segment. This approach aligns memory allocation with the program's structure, facilitating modular design and independent management of program components. Introduced in the Multics operating system, segmentation allows processes to view memory as a collection of these logical segments rather than a linear address space.[42] The operating system uses a per-process segment table to map logical addresses to physical memory. Each entry in the segment table includes the base address of the segment in physical memory, a limit specifying the segment's size, and protection bits that enforce access controls such as read, write, or execute permissions. During address translation, a logical address consisting of a segment identifier and an offset is used to index the segment table; the offset is then added to the base address to compute the physical address, with a bounds check against the limit to prevent overruns. This mechanism provides fine-grained protection and sharing capabilities, as segments can be marked for inter-process access.[43] Hybrid systems combine segmentation with paging to leverage the strengths of both techniques, where each segment is further subdivided into fixed-size pages for allocation in physical memory. In Multics, this integration used hardware support for segmentation at the logical level and paging for efficient physical placement, enabling large virtual address spaces while mitigating some fragmentation issues. Such combined approaches improve efficiency by allowing variable-sized logical divisions without the full overhead of pure segmentation.[42] The primary advantages of segmentation include its intuitive mapping to program modules, which supports code reusability, easier debugging, and protection at meaningful boundaries. However, it suffers from external fragmentation due to variable segment sizes, which can leave unusable gaps in physical memory, and incurs overhead from maintaining and searching segment tables. Despite these drawbacks, segmentation remains influential in systems emphasizing logical organization over uniform partitioning.[43]Allocation Algorithms

Contiguous Allocation

Contiguous allocation is a fundamental memory management technique in operating systems where each process receives a single, continuous block of physical memory to execute. This approach simplifies address translation and access but limits multiprogramming efficiency due to the need for unbroken space. In its simplest form, single contiguous allocation—common in early monoprogramming systems—dedicates the entire available user memory (excluding the operating system portion) to one process at a time, allowing straightforward loading but restricting concurrent execution.[44][45] To support multiprogramming, contiguous allocation often employs multiple partitions, dividing memory into fixed or variable blocks for process placement. Fixed partitioning pre-divides memory into fixed-sized blocks of predetermined sizes (which may be equal or unequal) at system initialization, with each block capable of holding one process regardless of its actual size. This leads to internal fragmentation, where allocated space exceeds the process's needs, leaving unusable remnants within the partition—for instance, a 4 MB partition holding a 1 MB process wastes 3 MB. The operating system tracks partition availability using a bitmap or simple status array, marking blocks as free or occupied to facilitate quick allocation checks.[45][46][47] In contrast, variable partitioning dynamically creates partitions sized exactly to fit incoming processes, minimizing internal fragmentation by avoiding oversized fixed blocks. However, as processes terminate, free memory scatters into non-adjacent "holes," causing external fragmentation where total free space suffices for a new process but no single contiguous block does—for example, separate 2 MB and 1 MB holes cannot accommodate a 3 MB request. To address this, the operating system performs compaction, relocating active processes to merge adjacent free spaces into larger blocks, though this incurs overhead from copying memory contents. These techniques can extend to virtual memory environments, where contiguous blocks are mapped to physical frames.[48][45][44] When selecting a suitable hole for allocation in either fixed or variable schemes, operating systems use heuristic strategies to balance speed and efficiency. The first-fit strategy scans free holes from the beginning and allocates the first one large enough, achieving O(n time complexity where n is the number of holes, making it fast but potentially increasing fragmentation by leaving larger remnants later. Best-fit searches all holes to select the smallest sufficient one, reducing wasted space but requiring full traversal for each request, often leading to slower performance. Worst-fit chooses the largest available hole to leave bigger remnants for future large processes, though it tends to exacerbate fragmentation and is generally less effective in simulations.[49][45][50]Non-Contiguous Allocation

Non-contiguous allocation techniques enable the operating system to assign memory to processes in dispersed blocks rather than requiring a single continuous region, thereby alleviating external fragmentation that plagues contiguous allocation approaches. These methods organize free memory using data structures that track scattered available blocks, allowing for more flexible utilization of physical memory. Common implementations include linked lists for chaining blocks, indexed structures for direct access, slab caches for kernel objects, and buddy systems for power-of-two sizing. Linked allocation manages free memory blocks through a chain where each block contains a pointer to the next available block, forming a singly linked list that simplifies traversal for finding suitable allocations. This structure supports first-fit, best-fit, or next-fit search strategies during allocation, with deallocation involving insertion back into the list while merging adjacent free blocks to reduce fragmentation. However, it introduces overhead from the pointer storage in each block—typically 4 to 8 bytes depending on architecture—and can suffer from sequential access inefficiencies when the list is long or unsorted.[51] Indexed allocation employs an index table or array where entries point directly to the starting addresses of data or free blocks, analogous to index blocks in file systems that reference non-adjacent disk sectors for a file. In memory contexts, this can manifest as segregated free lists indexed by block size classes, enabling O(1) access to appropriate pools for requests of varying sizes and reducing search time compared to a single linear list. The approach minimizes pointer overhead within blocks but requires additional space for the index structure itself, which grows with the number of supported size classes; for instance, systems might use 16 to 64 bins for common allocation granularities. While effective for reducing external fragmentation, large indices can lead to internal fragmentation if size classes are coarse.[51] Slab allocation preallocates fixed-size pools of memory for frequently used kernel objects, such as process control blocks or inode structures, to minimize initialization costs and fragmentation from small, variable requests. Each slab is a contiguous cache of objects in one of three states—full, partial, or empty—managed via bitmaps or lists within the slab to track availability; partial slabs are preferred for allocations to balance load. Introduced in SunOS 5.4, this method reduces allocation latency to near-constant time by avoiding per-object metadata searches, with empirical results showing up to 20% memory savings in kernel workloads due to decreased overhead. It addresses limitations of general-purpose allocators by specializing caches per object type, though it demands careful tuning of slab sizes to match object lifecycles.[52] The buddy system divides memory into power-of-two sized blocks, allocating the smallest fitting block for a request and recursively splitting larger blocks as needed, while deallocation merges adjacent "buddy" blocks of equal size to reform larger units. This logarithmic-time operation (O(log N) for N total blocks) ensures efficient coalescing without full scans, originating from early designs for fast storage management. Widely adopted in modern kernels like Linux for page-frame allocation, it handles requests from 4 KB pages up to gigabytes, with internal fragmentation bounded to 50% in the worst case but typically lower under mixed workloads; for example, simulations show average utilization above 80% for bursty allocation patterns. The method excels in environments with variable-sized requests but can waste space on non-power-of-two alignments.[53][54]Manual Management in Programming

Stack and Heap Allocation

In manual memory management, the stack serves as a last-in, first-out (LIFO) data structure primarily used for allocating local variables, function parameters, and temporary data during program execution.[55] Allocation and deallocation on the stack occur automatically through the compiler and runtime system, typically managed via stack frames that are pushed and popped as functions are called and return.[56] Each stack frame often includes a frame pointer that references the base of the current activation record, though this is optional in many architectures and optimizations, facilitating access to local variables and linkage to the previous frame, which ensures efficient, bounded allocation without explicit programmer intervention.[57] The operating system allocates a dedicated stack region for each thread upon creation, often with a fixed default size such as 8 MB in many Unix-like systems, to support recursive calls and nested function invocations.[58] The heap, in contrast, provides a dynamic memory region for runtime allocation requests that exceed the structured, temporary nature of stack usage, such as for data structures with variable lifetimes or sizes determined at execution time.[59] Heap management is typically handled by the operating system or language runtime, with mechanisms like the sbrk() system call in Unix extending the heap boundary by adjusting the "program break" to incorporate additional virtual memory pages as needed.[60] Unlike the stack, heap allocations can occur at arbitrary locations within the free space and support deallocation in any order, allowing flexibility for complex data structures but requiring explicit programmer control to avoid inefficiencies.[61] Key differences between stack and heap allocation lie in their performance characteristics and constraints: the stack offers rapid allocation and deallocation due to its contiguous, LIFO organization and automatic management, making it suitable for short-lived data, but it is limited to fixed-size regions per thread, potentially restricting depth in recursive scenarios.[62] The heap, while slower due to the overhead of searching for suitable free blocks and updating metadata, accommodates variable-sized and long-lived allocations across the program's lifetime, though it is prone to issues like fragmentation if deallocations are mismanaged.[63] Both the stack and heap reside within a process's virtual address space, mapped to physical memory by the operating system as demands arise.[64] Potential issues with stack and heap usage include overflows that can lead to program crashes or security vulnerabilities. Stack overflow occurs when excessive recursion or deep function call chains exceed the allocated stack size, causing the stack pointer to overrun into adjacent memory regions.[65] Heap exhaustion, resulting from inadequate deallocation practices such as memory leaks where allocated blocks are not freed despite no longer being needed, can deplete available heap space and force the program to terminate or trigger out-of-memory errors.[66]Dynamic Allocation Strategies

In programming languages like C and C++, dynamic memory allocation allows programs to request and release memory at runtime from the heap, complementing fixed stack allocation for local variables. The primary APIs for this aremalloc and free in C, which allocate a block of the specified size in bytes and return it to the free pool, respectively.[67] In C++, the new and delete operators extend this functionality by allocating memory via operator new (often implemented using malloc) and invoking constructors, while delete calls destructors before deallocation.[68] These mechanisms rely on underlying allocators that manage free blocks to minimize waste and overhead.

A core strategy in these allocators is coalescing, which merges adjacent free blocks upon deallocation to prevent external fragmentation, where usable space is scattered in small, non-contiguous pieces.[69] For example, if two neighboring blocks of 4 KB and 8 KB are freed, coalescing combines them into a single 12 KB block, reducing the number of fragments and improving future allocation efficiency. This immediate coalescing occurs during free or delete, though deferred variants delay merging to trade minor space overhead for faster deallocation times.[67]

Sequential fit algorithms represent a foundational approach, traversing a list of free blocks to select one for allocation. First-fit selects the initial block meeting or exceeding the request size, offering O(n) time where n is the number of free blocks but potentially leading to fragmentation by leaving larger remnants at the list's start. Best-fit, conversely, chooses the smallest suitable block to minimize leftover space, achieving lower fragmentation (often under 1% in address-ordered variants) at the cost of higher search times, sometimes mitigated by tree structures.[67] These methods balance simplicity with performance but scale poorly in heaps with many fragments.

To address these limitations, segregated lists partition free blocks into multiple bins by size classes (e.g., powers of two), enabling faster allocation by directly searching the relevant bin rather than the entire list. This approximates best-fit behavior while reducing average fragmentation to below 1% across workloads, as seen in implementations like Doug Lea's dlmalloc, which uses 64 bins for small objects and larger trees for bigger ones.[67] Dlmalloc, a widely adopted allocator since 1987, is single-threaded, but derivatives like ptmalloc (used in glibc since 1996) support multithreading via per-thread arenas to minimize lock contention, enhancing scalability in concurrent environments.[70][71]

Fragmentation mitigation further involves bin sorting and address-ordered lists. Bins are often maintained in size order within segregated schemes, allowing quick access to exact or near-exact fits and reducing internal fragmentation (wasted space within allocated blocks) by up to 50% compared to unsorted lists. Address-ordered lists sort free blocks by memory address, facilitating efficient coalescing and first-fit searches that mimic best-fit results with low overhead, yielding fragmentation rates under 1% in empirical tests.[67] Allocation overhead metrics, such as per-block headers (typically 8-16 bytes), contribute to space trade-offs, but these are offset by reduced search times.

Efficiency in these strategies hinges on time-space trade-offs, particularly with freelists. Segregated freelists enable O(1) amortized allocation and deallocation for common sizes by popping from bin heads, though coalescing and splitting introduce occasional O(log n) costs for larger blocks; overall, this yields high throughput with fragmentation under 1% in balanced implementations.[72] In contrast, exhaustive sequential fits may incur O(n) times, making them less suitable for large-scale applications without optimizations like those in dlmalloc.[67]