Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

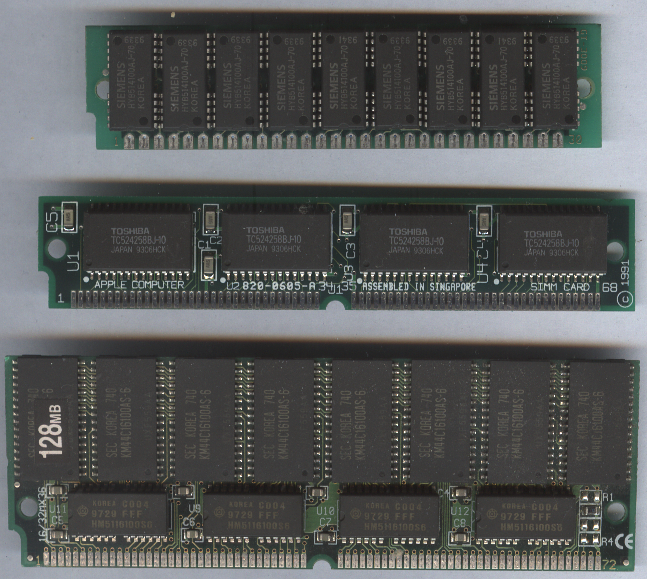

A SIMM (single in-line memory module) is a type of memory module used in computers from the early 1980s to the early 2000s. It is a printed circuit board upon which multiple random-access memory Integrated circuit chips are attached to one or both sides.[1] It differs from a dual in-line memory module (DIMM), the most predominant form of memory module since the late 1990s, in that the contacts on a SIMM are redundant on both sides of the module. SIMMs were standardised under the JEDEC JESD-21C standard.

Most early PC motherboards (8088-based PCs, XTs, and early ATs) used socketed DIP chips for DRAM. As computer memory capacities grew, memory modules were used to save motherboard space and ease memory expansion. Instead of plugging in eight or nine single DIP chips, only one additional memory module was needed to increase the memory of the computer.

History

[edit]SIMMs were invented in 1983 by James E. Clayton[2] at Wang Laboratories with subsequent patents granted in 1987.[3] [4] Wang Laboratories litigated both patents against multiple companies.[5][6][7][8][9] The original memory modules were built upon ceramic substrates with 64K Hitachi "flip chip" parts and had pins, i.e. single in-line package (SIP) packaging.[2] SIMMs using pins are usually called SIP or SIPP memory modules to distinguish them from the more common modules using edge connectors.

The first variant of SIMMs has 30 pins and provides 8 bits of data (plus a 9th error-detection bit in parity SIMMs). They were used in AT-compatible (286-based, e.g., Wang APC[10]), 386-based, 486-based, Macintosh Plus, Macintosh II, Quadra, Atari STE microcomputers, Wang VS minicomputers and Roland electronic samplers.

The second variant of SIMMs has 72 pins and provides 32 bits of data (36 bits in parity and ECC versions). These appeared first in the early 1990s in later models of the IBM PS/2, and later in systems based on the 486, Pentium, Pentium Pro, early Pentium II, and contemporary/competing chips of other brands. By the mid-90s, 72-pin SIMMs had replaced 30-pin SIMMs in new-build computers, and were starting to themselves be replaced by DIMMs.

Non-IBM PC computers such as UNIX workstations may use proprietary non-standard SIMMs. The Macintosh IIfx uses proprietary non-standard SIMMs with 64 pins.

DRAM technologies used in SIMMs include FPM (Fast Page Mode memory, used in all 30-pin and early 72-pin modules), and the higher-performance EDO DRAM (used in later 72-pin modules).

Due to the differing data bus widths of the memory modules and some processors, sometimes several modules must be installed in identical pairs or in identical groups of four to fill a memory bank. The rule of thumb is a 286, 386SX, 68000 or low-end 68020 / 68030 (e.g. Atari Falcon, Mac LC) system (using a 16 bit wide data bus) would require two 30-pin SIMMs for a memory bank. On 386DX, 486, and full-spec 68020 through 68060 (e.g. Atari TT, Amiga 4000, Mac II) systems (32 bit data bus), either four 30-pin SIMMs or one 72-pin SIMM are required for one memory bank. On Pentium systems (data bus width of 64 bits), two 72-pin SIMMs are required. However, some Pentium systems have support for a "half bank mode", in which the data bus would be shortened to only 32 bits to allow operation of a single SIMM. Conversely, some 386 and 486 systems use what is known as "memory interleaving", which requires twice as many SIMMs and effectively doubles the bandwidth.

The earliest SIMM sockets were conventional push-type sockets. These were soon replaced by ZIF sockets in which the SIMM was inserted at an angle, then tilted into an upright position. To remove one, the two metal or plastic clips at each end must be pulled to the side, then the SIMM must be tilted back and pulled out (low-profile sockets reversed this convention somewhat, like SODIMMs - the modules are inserted at a "high" angle, then pushed down to become more flush with the motherboard). The earlier sockets used plastic retainer clips which were found to break, so steel clips replaced them.

Some SIMMs support presence detect (PD). Connections are made to some of the pins that encode the capacity and speed of the SIMM, so that compatible equipment can detect the properties of the SIMM. PD SIMMs can be used in equipment which does not support PD; the information is ignored. Standard SIMMs can easily be converted to support PD by fitting jumpers, if the SIMMs have solder pads to do so, or by soldering wires on.[11]

30-pin SIMMs

[edit]

Standard sizes: 256 KB, 1 MB, 4 MB, 16 MB.

30-pin SIMMs have 12 address lines, which can provide a total of 24 address bits. With an 8-bit data width, this leads to an absolute maximum capacity of 16 MB for both parity and non-parity modules (the additional redundancy-bit chip usually does not contribute to the usable capacity).

| Pin # | Name | Signal description | Pin # | Name | Signal description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VCC | +5 VDC | 16 | DQ4 | Data 4 | |

| 2 | /CAS | Column address strobe | 17 | A8 | Address 8 | |

| 3 | DQ0 | Data 0 | 18 | A9 | Address 9 | |

| 4 | A0 | Address 0 | 19 | A10 | Address 10 | |

| 5 | A1 | Address 1 | 20 | DQ5 | Data 5 | |

| 6 | DQ1 | Data 1 | 21 | /WE | Write enable | |

| 7 | A2 | Address 2 | 22 | VSS | Ground | |

| 8 | A3 | Address 3 | 23 | DQ6 | Data 6 | |

| 9 | VSS | Ground | 24 | A11 | Address 11 | |

| 10 | DQ2 | Data 2 | 25 | DQ7 | Data 7 | |

| 11 | A4 | Address 4 | 26 | QP* | Data parity out | |

| 12 | A5 | Address 5 | 27 | /RAS | Row address strobe | |

| 13 | DQ3 | Data 3 | 28 | /CASP* | Parity column address strobe | |

| 14 | A6 | Address 6 | 29 | DP* | Data parity in | |

| 15 | A7 | Address 7 | 30 | VCC | +5 VDC |

* Pins 26, 28 and 29 are not connected on non-parity SIMMs.

72-pin SIMMs

[edit]

Standard sizes: 1 MB, 2 MB, 4 MB, 8 MB, 16 MB, 32 MB, 64 MB, 128 MB (the standard also defines 3.3 V modules with additional address lines and up to 2 GB)

With 12 address lines, which can provide a total of 24 address bits, two ranks of chips, and 32-bit data output, the absolute maximum capacity is 227 = 128 MB.

| Pin # | Name | Signal description | Pin # | Name | Signal description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VSS | Ground | 37 | MDP1* | Data parity 1 (MD8..15) | |

| 2 | MD0 | Data 0 | 38 | MDP3* | Data parity 3 (MD24..31) | |

| 3 | MD16 | Data 16 | 39 | VSS | Ground | |

| 4 | MD1 | Data 1 | 40 | /CAS0 | Column address strobe 0 | |

| 5 | MD17 | Data 17 | 41 | /CAS2 | Column address strobe 2 | |

| 6 | MD2 | Data 2 | 42 | /CAS3 | Column address strobe 3 | |

| 7 | MD18 | Data 18 | 43 | /CAS1 | Column address strobe 1 | |

| 8 | MD3 | Data 3 | 44 | /RAS0 | Row address strobe 0 | |

| 9 | MD19 | Data 19 | 45 | /RAS1† | Row address strobe 1 | |

| 10 | VCC | +5 VDC | 46 | NC | Not connected | |

| 11 | NU [PD5#] | Not used [presence detect 5 (3v3)] | 47 | /WE | Read/write enable | |

| 12 | MA0 | Address 0 | 48 | NC [/ECC#] | Not connected [ECC presence (if grounded) (3v3)] | |

| 13 | MA1 | Address 1 | 49 | MD8 | Data 8 | |

| 14 | MA2 | Address 2 | 50 | MD24 | Data 24 | |

| 15 | MA3 | Address 3 | 51 | MD9 | Data 9 | |

| 16 | MA4 | Address 4 | 52 | MD25 | Data 25 | |

| 17 | MA5 | Address 5 | 53 | MD10 | Data 10 | |

| 18 | MA6 | Address 6 | 54 | MD26 | Data 26 | |

| 19 | MA10 | Address 10 | 55 | MD11 | Data 11 | |

| 20 | MD4 | Data 4 | 56 | MD27 | Data 27 | |

| 21 | MD20 | Data 20 | 57 | MD12 | Data 12 | |

| 22 | MD5 | Data 5 | 58 | MD28 | Data 28 | |

| 23 | MD21 | Data 21 | 59 | VCC | +5 VDC | |

| 24 | MD6 | Data 6 | 60 | MD29 | Data 29 | |

| 25 | MD22 | Data 22 | 61 | MD13 | Data 13 | |

| 26 | MD7 | Data 7 | 62 | MD30 | Data 30 | |

| 27 | MD23 | Data 23 | 63 | MD14 | Data 14 | |

| 28 | MA7 | Address 7 | 64 | MD31 | Data 31 | |

| 29 | MA11 | Address 11 | 65 | MD15 | Data 15 | |

| 30 | VCC | +5 VDC | 66 | NC [/EDO#] | Not connected [EDO presence (if grounded) (3v3)] | |

| 31 | MA8 | Address 8 | 67 | PD1x | Presence detect 1 | |

| 32 | MA9 | Address 9 | 68 | PD2x | Presence detect 2 | |

| 33 | /RAS3† | Row address strobe 3 | 69 | PD3x | Presence detect 3 | |

| 34 | /RAS2 | Row Address Strobe 2 | 70 | PD4x | Presence detect 4 | |

| 35 | MDP2* | Data parity 2 (MD16..23) | 71 | NC [PD (ref)#] | Not connected [presence detect (ref) (3v3)] | |

| 36 | MDP0* | Data parity 0 (MD0..7) | 72 | VSS | Ground |

* Pins 35, 36, 37 and 38 are not connected on non-parity SIMMs.[12]

† /RAS1 and /RAS3 are only used on two-rank SIMMS: 2, 8, 32, and 128 MB.

# These lines are only defined on 3.3 V modules.

x Presence-detect signals are detailed in JEDEC standard.

Proprietary SIMMs

[edit]GVP 64-pin

[edit]Several CPU cards from Great Valley Products for the Commodore Amiga used special 64-pin SIMMs (32 bits wide, 1, 4 or 16 MB, 60 ns).

Apple 64-pin

[edit]Dual-ported 64-pin SIMMs were used in Apple Macintosh IIfx computers to allow overlapping read/write cycles (1, 4, 8, 16 MB, 80 ns).[13][14]

| Pin # | Name | Signal description | Pin # | Name | Signal description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GND | Ground | 33 | Q4 | Data output bus, bit 4 | |

| 2 | NC | Not connected | 34 | /W4 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 4 | |

| 3 | +5V | +5 volts | 35 | A8 | Address bus, bit 8 | |

| 4 | +5V | +5 volts | 36 | NC | Not connected | |

| 5 | /CAS | Column address strobe | 37 | A9 | Address bus, bit 9 | |

| 6 | D0 | Data input bus, bit 0 | 38 | A10 | Address bus, bit 10 | |

| 7 | Q0 | Data output bus, bit 0 | 39 | A11 | Address bus, bit 11 | |

| 8 | /W0 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 0 | 40 | D5 | Data input bus, bit 5 | |

| 9 | A0 | Address bus, bit 0 | 41 | Q5 | Data output bus, bit 5 | |

| 10 | NC | Not connected | 42 | /W5 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 5 | |

| 11 | A1 | Address bus, bit 1 | 43 | NC | Not connected | |

| 12 | D1 | Data input bus, bit 1 | 44 | NC | Not connected | |

| 13 | Q1 | Data output bus, bit 1 | 45 | GND | Ground | |

| 14 | /W1 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 1 | 46 | D6 | Data input bus, bit 6 | |

| 15 | A2 | Address bus, bit 2 | 47 | Q6 | Data output bus, bit 6 | |

| 16 | NC | Not connected | 48 | /W6 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 6 | |

| 17 | A3 | Address bus, bit 3 | 49 | NC | Not connected | |

| 18 | GND | Ground | 50 | D7 | Data input bus, bit 7 | |

| 19 | GND | Ground | 51 | Q7 | Data output bus, bit 7 | |

| 20 | D2 | Data input bus, bit 2 | 52 | /W7 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 7 | |

| 21 | Q2 | Data output bus, bit 2 | 53 | /QB | Reserved (parity) | |

| 22 | /W2 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 2 | 54 | NC | Not connected | |

| 23 | A4 | Address bus, bit 4 | 55 | /RAS | Row address strobe | |

| 24 | NC | Not connected | 56 | NC | Not connected | |

| 25 | A5 | Address bus, bit 5 | 57 | NC | Not connected | |

| 26 | D3 | Data input bus, bit 3 | 58 | Q | Parity-check output | |

| 27 | Q3 | Data output bus, bit 3 | 59 | /WWP | Write wrong parity | |

| 28 | /W3 | Write-enable input for RAM IC 3 | 60 | PDCI | Parity daisy-chain input | |

| 29 | A6 | Address bus, bit 6 | 61 | +5V | +5 volts | |

| 30 | NC | Not connected | 62 | +5V | +5 volts | |

| 31 | A7 | Address bus, bit 7 | 63 | PDCO | Parity daisy-chain output | |

| 32 | D4 | Data input bus, bit 4 | 64 | GND | Ground |

HP LaserJet

[edit]72-pin SIMMs with non-standard presence detect (PD) connections.

See also

[edit]- Dual in-line package (DIP)

- Single in-line package (SIP)

- Zig-zag in-line package (ZIP)

- Dual in-line memory module (DIMM)

References

[edit]- ^ "What is DIMM(Dual Inline Memory Module)?". GeeksforGeeks. 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2024-04-07.

In the case of SIMM, the connectors are only present on the single side of the module...DIMM has a row of connectors on both sides(front and back) of the module

- ^ a b Clayton, James E. (1983). Low-cost, high-density memory packaging: A 64K X 9 DRAM SIP module, The International journal for hybrid microelectronics.

- ^ U.S. patent 4,656,605 - Single in-line memory module

- ^ U.S. patent 4,727,513 - Signal in-line memory module

- ^ "Wang Laboratories, Inc., Plaintiff/cross-appellant, v. Toshiba Corporation; Toshiba America Electronic Components, inc.; Toshiba America Information Systems, Inc., defendants-appellants, and Nec Corporation; Nec Electronics Inc. and Nec Technologies, inc., Defendants-appellants, and Molex Incorporated, Defendant, 993 F.2d 858 (Fed. Cir. 1993)". justia.com. May 10, 1993. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Wang Laboratories, Inc., Plaintiff-appellee, v. Clearpoint Research Corporation, Defendant-appellant, 5 F.3d 1504 (Fed. Cir. 1993)". justia.com. July 23, 1993. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Wang Laboratories v. MITSUBISHI ELECTRONICS, 860 F. Supp. 1448 (C.D. Cal. 1993)". justia.com. December 17, 1993. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Wang Laboratories, Inc., Plaintiff-appellant, v. Mitsubishi Electronics America, Inc. and Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, Defendants/cross-appellants, 103 F.3d 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1997)". justia.com. January 3, 1997. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Wang Laboratories v. OKI ELECTRIC INDUSTRY CO., 15 F. Supp. 2d 166 (D. Mass. 1998)". justia.com. July 31, 1998. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Wang Plays A Strong PC-Compatible Hand, PC Magazine, October 1, 1985

- ^ "Making Standard SIMMs Work – Memory Upgrade on the HP LaserJet 6MP/5MP Article on fitting jumpers to add Presence Detect to standard SIMMs". Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ JEDEC Standard No. 21-C, Section 4.4.2 "72 pin SIMM DRAM Module Family".

- ^ Macintosh IIfx.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (1990). Guide to the Macintosh Family Hardware (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley, Inc. p. 230.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (1990). Guide to the Macintosh Family Hardware (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley, Inc. pp. 214–222.