Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Electrical synapse.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electrical synapse

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Electrical synapse

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

An electrical synapse is a specialized junction between adjacent neurons that enables direct, bidirectional transmission of electrical signals and small molecules through gap junctions, which are channels formed by connexin proteins such as connexin-36 (Cx36).[1][2] Unlike chemical synapses, which rely on neurotransmitter release and receptor activation across a synaptic cleft, electrical synapses permit nearly instantaneous ion flow (with delays under 1 millisecond) driven by voltage gradients, facilitating rapid synchronization of neuronal activity.[1]

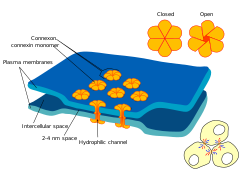

These synapses are ubiquitous across nervous systems, from invertebrates like crayfish to vertebrate brains including the mammalian neocortex, retina, and hypothalamus, particularly among inhibitory interneurons and in sensory structures like the retina, where they can form a substantial portion of local connections.[2][4] Structurally, gap junctions consist of paired hemichannels (connexons), each a hexamer of connexins that align to form aqueous pores approximately 2 nm in diameter, allowing passage of ions like potassium and calcium, as well as metabolites such as ATP and second messengers up to several hundred daltons in size.[1][4] This direct coupling supports diverse functions, including the coordination of escape responses in arthropods, rhythmic hormone secretion in the hypothalamus, sensory processing in the retina, and modulation of cortical oscillations, while also exhibiting plasticity through mechanisms like phosphorylation that can alter conductance on timescales from milliseconds to days.[1][2][4]

Electrical synapses often coexist with chemical synapses in hybrid configurations, enhancing circuit flexibility and efficiency by combining speed with the modulatory capabilities of neurotransmitters, and their dysregulation has been implicated in neurological disorders such as epilepsy and neurodevelopmental conditions.[2][4]

[9][10][7]

Introduction and Basics

Definition

An electrical synapse is a specialized intercellular junction that establishes direct cytoplasmic continuity between adjacent cells, primarily neurons, via gap junctions, enabling the passive flow of electrical currents and small signaling molecules.[1] These junctions form when the plasma membranes of two cells approach closely, creating a conduit for direct intercellular communication without the need for vesicular release or receptor activation.[5] Key properties of electrical synapses include their bidirectional nature, allowing current to flow in either direction based on the electrochemical gradient, and their low electrical resistance, which permits near-instantaneous transmission of signals.[1] Unlike chemical synapses, they lack a synaptic cleft and do not involve neurotransmitters; instead, they provide a straightforward pathway for ions such as potassium and calcium, as well as small molecules under 1 kDa in molecular weight, such as cyclic AMP or ATP.[6] This direct coupling supports rapid synchronization of cellular activity, distinguishing electrical synapses from mere cell adhesion structures that do not facilitate signaling.[5] Structurally, the core feature is a narrow intercellular gap of approximately 2–4 nm between the apposed cell membranes, bridged by aligned channels that form the gap junction pore.[5] This configuration ensures minimal impedance to ion diffusion while maintaining cellular integrity.[1]Comparison with Chemical Synapses

Electrical synapses differ fundamentally from chemical synapses in their mechanisms of intercellular communication. Chemical synapses transmit signals unidirectionally across a synaptic cleft measuring 20-40 nm, where presynaptic neurons release neurotransmitters that diffuse to bind postsynaptic receptors, enabling signal modulation and potential amplification through receptor activation and second-messenger cascades.[7][8] In contrast, electrical synapses facilitate bidirectional transmission via direct cytoplasmic connections formed by gap junctions, allowing ions and small molecules to pass between cells without a cleft, resulting in near-instantaneous signal propagation with minimal delay of less than 0.1 ms.[9][10] The synaptic delay in chemical transmission, typically 0.5-4 ms, arises from the time required for neurotransmitter release, diffusion, and receptor binding, which introduces opportunities for synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation or depression through changes in neurotransmitter release probability or receptor sensitivity.[9] Electrical synapses, however, exhibit faithful signal propagation without inherent amplification or modulation, as the current flow is governed by the conductance of gap junction channels, though their strength can be regulated by voltage, pH, or phosphorylation.[9] This direct coupling ensures rapid synchronization of electrical activity between coupled cells but limits the complexity of signal processing compared to chemical synapses.[10] In many neural circuits across species, electrical and chemical synapses coexist, often forming hybrid or mixed synapses where gap junctions are closely apposed to chemical synaptic specializations, allowing integrative interactions such as electrical coupling modulating chemical transmission efficacy.[9] For instance, in teleost fish Mauthner cells, mixed synapses enable rapid escape responses by combining the speed of electrical transmission with the specificity of chemical signaling.[9]| Aspect | Electrical Synapses | Chemical Synapses |

|---|---|---|

| Directionality | Bidirectional | Unidirectional |

| Transmission Speed | Near-instantaneous (<0.1 ms delay) | Delayed (0.5-4 ms) |

| Molecular Mediators | Gap junctions (connexins/innexins) | Neurotransmitters and receptors |

| Signal Processing | Faithful propagation, no amplification | Amplification and modulation possible |

| Structural Gap | Direct cytoplasmic continuity (~3.5 nm gap, ~1.5 nm pores) | Synaptic cleft (20-40 nm) |

Structural Components

Gap Junctions

Gap junctions are the fundamental structural units enabling direct electrical coupling between adjacent cells in electrical synapses. They form through the docking of paired hemichannels, known as connexons, one from each neighboring cell, which align precisely in the extracellular space to create a continuous aqueous pore spanning the intercellular gap. This assembly process ensures the establishment of low-resistance pathways for ion and small molecule exchange, with the connexons interacting via non-covalent bonds to maintain stability.[11] The ultrastructure of a gap junction channel features a narrow pore with a diameter of 1.2 to 2 nm, allowing selective passage of ions and metabolites up to about 1 kDa in size, and a total length of approximately 14 nm that traverses the lipid bilayers of both cells (each ~4-5 nm) plus the intervening gap of 2-4 nm. Within the plasma membrane, these channels are organized into extensive hexagonal arrays, often numbering thousands per junction, which optimize packing density and facilitate efficient intercellular communication. The protein composition of connexons, primarily involving connexin family members, underpins this architecture, though specific isoforms are detailed elsewhere.[12][13][14] Biophysically, individual gap junction channels display unitary conductances typically ranging from 50 to 300 pS, reflecting variability across different cell types and conditions, which determines the overall strength of electrical coupling. These channels also exhibit voltage-dependent gating, where transjunctional voltage differences modulate opening and closing, thereby regulating conductance in response to cellular activity gradients. This gating mechanism involves conformational changes in the channel pore, sensitive to potentials as low as 20-50 mV.[15][16] Imaging techniques, particularly electron microscopy, have been instrumental in visualizing gap junction organization, revealing large plaque-like assemblies of channels embedded in the membrane. Freeze-fracture electron microscopy, for instance, shows these plaques as crystalline arrays with intramembrane particles arranged hexagonally, providing direct evidence of their dense, ordered structure at the nanoscale. Such observations confirm the scale and uniformity essential for synchronized cellular function in tissues like the nervous system.[14]Connexins and Pannexins

Electrical synapses in vertebrates are primarily mediated by gap junctions formed by connexins, a family of transmembrane proteins encoded by 21 genes in the human genome.[17] These proteins share a conserved topology consisting of four α-helical transmembrane domains, two extracellular loops that facilitate docking between adjacent cells, one intracellular loop, and both amino- and carboxy-terminal domains located intracellularly. Six connexin monomers oligomerize to form a connexon, or hemichannel, which docks with an opposing connexon from a neighboring cell to create a complete intercellular channel. Among the isoforms, connexin 36 (Cx36, encoded by GJD2) is particularly prominent in neuronal tissues, where it supports electrical coupling between specific neuron populations such as those in the retina and inferior olive. Pannexins represent a distinct family of channel-forming proteins with three isoforms in mammals (Panx1, Panx2, and Panx3), which exhibit sequence homology to invertebrate innexins but differ from connexins in their inability to form traditional gap junctions due to glycosylation at extracellular sites that prevents docking.[18] Unlike connexin-based channels, pannexin hemichannels form larger pores, permitting the passage of molecules up to approximately 1 kDa, such as ATP, and are predominantly involved in non-neuronal intercellular communication through paracrine signaling rather than direct electrical coupling.[19] Panx1 is the most widely expressed isoform and contributes to such processes in tissues like glia and endothelium, while Panx2 and Panx3 show more restricted patterns, including in the central nervous system and skeletal tissues. The expression of connexins and pannexins is tightly regulated at the genetic level, with tissue-specific promoters driving isoform diversity; for instance, Cx36 is predominantly expressed in brain neurons, whereas Cx43 dominates in cardiac and vascular tissues.[20] Post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation, play a critical role in channel regulation, affecting trafficking, assembly into hemichannels, and gating properties—multiple serine and tyrosine residues serve as targets for kinases such as protein kinase C (PKC) and Src, modulating channel permeability and stability.[21] Similar phosphorylation events influence pannexin channels, with Panx1 activity enhanced by Src kinase-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation in response to extracellular signals.[22] Mutations in connexin genes underlie several hereditary disorders, highlighting their physiological importance. In connexin 26 (Cx26, encoded by GJB2), the common 35delG frameshift mutation disrupts channel function, leading to nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness by impairing potassium recycling in the cochlea.[23] Similarly, polymorphisms and missense mutations in the Cx36 gene (GJD2), such as the rs3743123 polymorphism, have been associated with increased susceptibility to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, likely through altered neuronal synchronization.[24] Pannexin mutations are less commonly linked to specific diseases, though functional alterations in Panx1 contributing to altered ATP release have been implicated in conditions like migraine and inflammation in non-neuronal contexts.[25]Mechanisms of Transmission

Ion and Molecule Flow

Electrical synapses enable the direct passage of small ions and molecules between coupled cells through gap junction channels, which typically allow the diffusion of species up to approximately 1 kDa in size.[26] Monovalent cations such as K⁺ and Na⁺, and second messengers including inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP₃) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) can permeate these channels, facilitating both electrical signaling and metabolic coupling. Larger biomolecules, such as proteins, are excluded due to the channel's size restriction.[26] The flow of ions and molecules across electrical synapses is driven by electrochemical gradients established between the cytoplasms of adjacent cells, with the direction and magnitude determined by differences in ion concentrations and membrane potentials.[27] This process exhibits ohmic conductance, meaning the junctional current flows linearly with the voltage difference, described by the equation where is the junctional current, is the junctional conductance, and and are the membrane potentials of the two connected cells. Channel proteins such as connexins form these pores, enabling the selective permeability observed.[28] In certain electrical synapses, conductance is asymmetric, leading to rectification where current flows more readily in one direction than the other. This property arises from heterotypic channel compositions or molecular asymmetries, as seen in the mixed synapses of fish Mauthner cells, where connexin 34.7 and connexin 35 form junctions that preferentially transmit current from the Mauthner neuron to the afferent (retrograde direction).[29][30]Electrical Coupling and Synchronization

Electrical coupling at synapses allows for the direct transfer of electrical signals between neurons, enabling coordinated activity across connected cells. The strength of this coupling is quantified by the coupling coefficient, defined as , where represents the membrane resistance of the cells and the junctional resistance of the gap junction.[28] This coefficient measures the fraction of voltage change in one cell that is transmitted to the coupled cell under steady-state conditions, with higher values indicating stronger synchronization potential. For instance, low junctional resistance enhances signal propagation, facilitating rapid alignment of membrane potentials.[28] Through this coupling, electrical synapses promote synchronization by enabling phase-locking of action potentials, particularly in inhibitory networks where precise timing is crucial for oscillatory rhythms. In neocortical inhibitory interneurons, electrical connections allow spikes to entrain phases, reducing variability in firing times and supporting network-level coherence, though action potential shape influences the degree of locking.[31] Similarly, in broader inhibitory ensembles, these synapses drive widespread synchronous activity by amplifying shared inhibitory inputs, ensuring that coupled neurons fire in unison to modulate excitatory circuits.[32] Plasticity in electrical coupling arises from activity-dependent modulation of junctional conductance, allowing synapses to strengthen or weaken based on neuronal firing patterns. High-frequency activity can up-regulate conductance, enhancing coupling and promoting tighter synchronization, while low-frequency or bursting patterns induce down-regulation, potentially desynchronizing cells to refine network dynamics.[33] Such bidirectional changes enable adaptive responses, with long-term potentiation observed in paired activity and depression in asynchronous inputs.[33] Modeling electrical coupling often employs equivalent circuit diagrams to simulate interactions between cells. These models represent each neuron as a resistor-capacitor network, with the gap junction as a connecting resistor between parallel - branches for the membranes, capturing voltage transfer and temporal dynamics during current injection. This framework reveals how variations in resistances affect overall network behavior, providing insights into synchronization stability without requiring detailed molecular parameters.Physiological Functions

In the Nervous System

Electrical synapses play a crucial role in the nervous system by enabling rapid signal transmission and precise neuronal integration, which are essential for behaviors requiring immediate responses and coordinated activity. In escape responses, such as the C-start in fish, electrical synapses facilitate ultrarapid coordination between Mauthner cells and downstream neurons, allowing the propagation of action potentials with minimal delay to trigger explosive tail flips in response to threats.[34] These mixed synapses, combining electrical and chemical components at club endings on Mauthner cells, ensure both speed and reliability in initiating the escape reflex, where delays as short as 5-10 milliseconds are critical for survival.[35] Beyond acute behaviors, electrical synapses contribute to oscillatory networks that support higher-order neural processing. In the mammalian cortex, connexin-36 (Cx36)-containing gap junctions between interneurons promote synchronized gamma rhythms (30-80 Hz), which are vital for cognitive functions like attention and sensory binding by enhancing inhibitory coupling and spike timing precision.[36] Disruption of these Cx36-mediated connections impairs gamma-frequency oscillations, leading to deficits in network synchrony that underpin perceptual integration.[9] During neural development, electrical synapses transiently form to guide neuronal migration and circuit assembly. Gap junctions allow the exchange of ions and small molecules between immature neurons, coordinating proliferation, differentiation, and tangential migration in the cortex, while also stabilizing early connections that mature into chemical synapses.[37] In the thalamus, for instance, Cx36-based electrical coupling influences inhibitory circuit formation by shaping dendritic arborization and synaptic specificity, ensuring proper network wiring before adult patterns emerge.[38] In pathologies like Parkinson's disease, dysfunction of gap junctions contributes to aberrant network desynchronization and pathological oscillations. In the globus pallidus, enhanced gap junction coupling between neurons promotes hypersynchronous beta-band activity (13-30 Hz), a hallmark of motor symptoms; pharmacological blockade or genetic disruption of these junctions induces desynchronization, reducing oscillatory power and alleviating parkinsonian-like tremors in animal models.[39] This highlights how gap junction dysregulation disrupts the balance of synchronization needed for normal basal ganglia function.[40]In Non-Neuronal Tissues

Electrical synapses, formed by gap junctions, play crucial roles in non-neuronal tissues by enabling direct electrical and metabolic coupling between cells, which coordinates essential physiological processes beyond neural signaling. In cardiac muscle, connexin 43 (Cx43) and connexin 40 (Cx40) are the primary proteins forming these gap junctions, facilitating the rapid spread of electrical impulses across cardiomyocytes to ensure synchronized contraction.[41] This coupling is vital for efficient heart rhythm, as disruptions in Cx43 expression or localization—such as dephosphorylation or lateralization during ischemia—can lead to slowed conduction and increased arrhythmia risk, including ventricular tachycardia. Similarly, Cx40 predominates in the atria and conduction system, supporting impulse propagation and preventing atrial fibrillation when functioning normally.[41] In smooth muscle, particularly vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), connexins such as Cx43 and Cx45 form gap junctions that mediate direct electrical and chemical coupling between adjacent VSMCs and between VSMCs and endothelial cells, enabling coordinated regulation of vascular tone and blood flow.[41] This intercellular communication allows the spread of depolarizing currents and second messengers, facilitating synchronized vasoconstriction or dilation in response to stimuli like sympathetic innervation. Disruptions in these connexin-based gap junctions can impair vasomotor responses, contributing to conditions such as hypertension.[42] Epithelial tissues, such as the liver, rely on connexin 32 (Cx32) for metabolic coupling that supports detoxification and overall hepatic function. Cx32 forms extensive gap junction networks among hepatocytes, enabling the intercellular exchange of ions, second messengers, and small metabolites like nucleotides and amino acids, which coordinate processes such as ammonia detoxification and glucose regulation.[43] Mutations in Cx32 cause X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a peripheral neuropathy affecting Schwann cells, while Cx32 dysfunction is separately implicated in liver pathologies, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and increased susceptibility to hepatocarcinogenesis, leading to disrupted metabolic homeostasis and toxin accumulation.[44][43] Another prominent example occurs in the ocular lens, where fiber cells are interconnected by gap junctions composed of connexins 46 (Cx46) and 50 (Cx50), ensuring transparency maintenance through electrical and metabolic coupling.[41] These junctions create a syncytium that circulates ions and antioxidants across the avascular lens, preventing oxidative stress and ion imbalances that could cause cataracts. Loss of Cx46 or Cx50 function, as observed in aging or genetic models, diminishes coupling conductance and compromises lens clarity by disrupting nutrient distribution and waste removal.[41]Occurrence Across Species

In Vertebrates

In mammals, electrical synapses exhibit reduced prevalence compared to invertebrates, with connexin 36 (Cx36) serving as the predominant protein forming gap junctions in the brain, particularly between GABAergic interneurons across various regions such as the neocortex, hippocampus, and inferior olive.[45][46] In contrast, connexin 43 (Cx43) dominates in cardiac tissue, where it mediates electrical coupling essential for coordinated myocardial contractions and impulse propagation.[47][46] This distribution underscores a specialized, rather than ubiquitous, role in mammalian physiology, with Cx36-based synapses supporting neuronal synchronization in specific circuits.[48] In fish, electrical synapses are far more abundant, especially in the hindbrain, where they enable rapid transmission critical for behaviors like the C-start escape response. For instance, in zebrafish, large gap junctions connect Mauthner cells and their counterparts, allowing near-instantaneous bilateral coordination of motor neurons for high-speed maneuvers.[49][50] This abundance facilitates the low-latency signaling required for survival in predatory environments, highlighting adaptations for velocity over precision in lower vertebrates.[51] Amphibians and birds feature prominent electrical synapses in the retina, where gap junctions couple horizontal cells, bipolar cells, and amacrine cells to enhance visual processing through lateral inhibition and synchronized responses to stimuli. In amphibian retinas, such as those of frogs, these junctions between photoreceptors and interneurons improve contrast detection and light adaptation.[52] Similarly, in birds like chickens, retinal electrical coupling supports spectral and temporal multiplexing, allowing efficient integration of color and motion cues for foraging and navigation.[53] These adaptations optimize parallel processing in the visual pathway, contributing to behavioral acuity in diverse ecological niches. An evolutionary trend in vertebrates shows a decline in the complexity and prevalence of electrical synapses from lower to higher taxa, with fish and amphibians displaying widespread CNS distribution for fast, synchronized activities, while mammals rely more on chemical synapses for nuanced modulation, relegating electrical ones to auxiliary roles.[54] This shift correlates with increasing neural circuit sophistication, where electrical coupling persists in select contexts like retinal and cardiac synchronization but diminishes overall.[55]In Invertebrates

Electrical synapses are particularly prevalent in the nervous systems of invertebrates, where they facilitate rapid signal transmission and synchronization essential for behaviors such as escape responses and coordinated movement. Unlike in vertebrates, where chemical synapses predominate, electrical synapses in invertebrates often comprise a substantial proportion of neural connections, enabling efficient propagation of action potentials across networks.[9] In the crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) giant fiber escape circuit, electrical synapses exhibit high density between sensory afferents, interneurons, and motor giants, which supports the swift coordination required for tail-flip escapes. These rectifying electrical synapses, first characterized in the lateral giant to motor giant pathway, allow unidirectional current flow that enhances the reliability of rapid signaling while minimizing delays.[56][57] The structural basis of electrical synapses in invertebrates relies on innexins, a family of proteins analogous to vertebrate connexins that assemble into gap junctions permitting direct ion flow between cells. Innexins share topological similarities with connexins, forming hexameric hemichannels that dock to create intercellular pores, but they evolved independently and exhibit distinct sequence motifs. In Drosophila melanogaster, there are eight innexin genes, with multiple splice isoforms expanding functional diversity; for instance, innexin ShakB localizes to gap junctions in the giant fiber system, promoting synchronized firing for visual escape responses.[58][59][60] In the marine mollusk Aplysia californica, electrical synapses contribute to the escape circuit by coupling command interneurons in the pleural ganglion, enabling phased coordination during siphon withdrawal and tail-arrested swimming behaviors. These junctions, formed by innexin-like proteins, allow electrotonic spread of depolarization to amplify sensory inputs and drive motor output with minimal latency.[61][62] In nematodes such as Caenorhabditis elegans, electrical synapses mediated by innexins play critical roles in locomotion, where specific isoforms like UNC-7 and UNC-9 form heterotypic channels that couple motor neurons for rhythmic undulation and backward escape maneuvers. Mutations in these innexins disrupt coordinated movement, underscoring their necessity for propagating synchronized activity across the ventral nerve cord during rapid behavioral responses.[63][64]Advantages and Limitations

Benefits

Electrical synapses offer several key advantages that contribute to their evolutionary persistence across species, primarily through their biophysical properties that enable efficient and rapid neuronal communication. One primary benefit is their exceptional transmission speed, allowing signals to propagate between coupled neurons in sub-millisecond timescales, which is crucial for rapid behavioral responses essential to survival, such as escape reflexes.[65] This direct ionic coupling bypasses the delays inherent in chemical synaptic transmission, facilitating near-instantaneous electrical signaling without the need for neurotransmitter release or receptor activation.[66] Another significant advantage lies in their ability to promote synchronization of neuronal activity. By enabling the direct flow of electrical current, electrical synapses allow ensembles of neurons to fire coherently, generating synchronized oscillations that support coordinated network functions, such as those involved in sensory processing like olfaction.[67] This coupling reduces voltage differences between connected cells, enhancing the precision and reliability of population-level responses in neural circuits.[30] Electrical synapses also provide metabolic efficiency by permitting the sharing of ions and small metabolites between cells, thereby reducing the overall energy expenditure compared to chemical synapses, which require costly processes like vesicle exocytosis and neurotransmitter synthesis.[66] This resource-sharing mechanism supports sustained activity in energy-constrained environments, such as during prolonged network oscillations.[68] Finally, the bidirectionality of electrical synapses, which is typical in many cases, enables reciprocal signaling, fostering feedback loops within hybrid circuits that integrate electrical and chemical transmission. This two-way communication enhances network flexibility and dynamic control, allowing adjustments in excitability and coordination that are vital for adaptive neural processing.[67]Drawbacks

Electrical synapses, formed by gap junctions, transmit signals passively without the amplification mechanisms inherent to chemical synapses, resulting in a lack of gain that limits the integration of multiple synaptic inputs into a stronger output. This passive conduction means that the postsynaptic potential is typically smaller or equal to the presynaptic one, preventing the summation and enhancement of signals that facilitate complex neural processing.[9] In contrast to chemical synapses, where neurotransmitter release and receptor activation allow for signal boosting, electrical synapses cannot amplify excitatory inputs into inhibitory responses or scale signal strength dynamically, constraining their role in circuits requiring precise gain control.[69] Another drawback is the potential for electrical synapses to facilitate the rapid spread of pathological activity, such as epileptiform discharges, across coupled neuron networks. Gap junctions enable direct electrical and metabolic coupling that can propagate abnormal synchrony without the filtering delays of chemical transmission, exacerbating conditions like epilepsy by allowing hyperexcitable states to disseminate quickly through otherwise healthy tissue.[70] For instance, in hippocampal circuits, enhanced gap junction coupling has been linked to the amplification and propagation of seizure-like activity, turning localized disturbances into widespread network failures.[71] Electrical synapses also exhibit reduced plasticity compared to their chemical counterparts, making them harder to modulate in response to activity-dependent changes. While chemical synapses undergo robust long-term potentiation or depression through molecular cascades involving receptors and second messengers, electrical synapses rely on more limited mechanisms like connexin phosphorylation, which offer less flexibility for circuit adaptation.[46] This relative rigidity can hinder learning and memory processes that depend on synaptic strengthening or weakening, as electrical coupling remains relatively fixed without the bidirectional modulation seen in chemical synapses.[72] Furthermore, electrical synapses are vulnerable to environmental perturbations such as changes in pH or elevated CO₂ levels, which can block gap junction conductance and disrupt neural circuits. Acidification or increased partial pressure of CO₂ directly gates connexin channels closed, uncoupling cells and impairing synchronization in pH-sensitive tissues like the brain.[73] For example, connexin26 gap junctions, common in neuronal contexts, close reversibly under hypercapnic conditions, potentially leading to transient failures in coupled networks during physiological stress like ischemia.[74]History and Research

Discovery and Early Studies

The discovery of electrical synapses emerged from electrophysiological investigations in the mid-20th century, challenging the prevailing view that all synaptic transmission was chemical. In 1957, Edwin J. Furshpan and David D. Potter provided the initial evidence while studying the giant motor synapse in the abdominal nerve cord of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Using intracellular microelectrodes inserted into pre- and post-synaptic elements, they recorded action potentials with latencies under 0.1 milliseconds, far shorter than those typical of chemical synapses, indicating direct electrical transmission through low-resistance pathways between neurons. This finding resolved early debates about the mechanism of rapid signal propagation in invertebrate escape circuits, where chemical diffusion would be too slow.[57] Building on this, Furshpan and Potter's 1959 study further characterized the synapse as rectifying—allowing current flow preferentially in one direction—based on voltage responses to current injection, confirming the existence of specialized low-resistance junctions in crayfish giant fibers. Concurrently, Akira Watanabe's 1958 work on the lobster Panulirus japonicus cardiac ganglion demonstrated synchronous bursting activity among interconnected neurons, with injected currents spreading with minimal attenuation, providing additional electrophysiological evidence for electrical coupling in invertebrate rhythmic networks. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, similar experiments in systems like the crayfish and shrimp stomatogastric ganglia revealed that hyperpolarizing or depolarizing currents passed between adjacent neurons with coupling coefficients often exceeding 0.5, underscoring low-resistance paths as a common feature of certain invertebrate synapses. Electron microscopy advanced these observations by revealing structural correlates. In 1963, J. David Robertson examined Mauthner cell synapses in the goldfish Carassius auratus brain and described "gap junctions" as regions of intimate membrane apposition, separated by a uniform 20 Å extracellular space, which aligned with the low electrical resistance measured electrophysiologically and suggested direct cytoplasmic continuity for ion flow. A pivotal confirmation of functional patency came from dye-coupling experiments in invertebrate neurons; for instance, early applications in crayfish giant interneurons during the late 1960s showed that injected dyes like Procion Yellow diffused between coupled cells, demonstrating that these junctions permitted not only ions but also small molecules to pass, thus validating their role in electrical signaling.[75]Recent Advances

In the 2010s, advances in optogenetics combined with voltage-sensitive dye (VSD) imaging have enabled high-resolution visualization of membrane potential dynamics in neuronal networks, revealing the rapid electrical coupling mediated by gap junctions during synchronized activity. For instance, all-optical electrophysiology techniques, integrating optogenetic perturbation and VSD fluorescence, have mapped interneuron connections and uncovered network-level propagation through electrical synapses in vivo, demonstrating sub-millisecond resolution for studying coupling strength and plasticity. These methods have highlighted how electrical synapses facilitate bidirectional signal flow in inhibitory circuits, providing insights into transient dynamics not resolvable by traditional electrophysiology.[76] Genetic knockout models, particularly Cx36-deficient mice, have elucidated the role of electrical synapses in maintaining neural rhythms. In Cx36-/- mice, the absence of functional neuronal gap junctions formed by connexin-36 leads to disrupted gamma-frequency oscillations (30-70 Hz) in the neocortex and hippocampus, impairing synchronous inhibitory activity essential for information processing. Recent studies using these models show that presynaptic electrical coupling via Cx36 coordinates rhythmic firing in olivary neurons, and its disruption results in asynchronous activity patterns, underscoring the protein's necessity for network coherence.[77][78][64] Therapeutic strategies targeting electrical synapses hold promise for treating epilepsy and cardiac diseases. In absence epilepsy models, pharmacological blockade of thalamic gap junctions reduces seizure-like activity by weakening neuroplastic changes in electrical coupling, suggesting connexin modulators as novel antiseizure agents distinct from ion channel or chemical synapse targets.[79] For cardiac arrhythmias, enhancing gap junction conductance with peptides like rotigaptide prevents conduction slowing in ischemic tissue, reducing vulnerability to reentrant circuits, while genetic interventions restoring connexin-43 expression in infarct borders suppress ventricular tachycardia.[80] More recent research as of 2025 has advanced the molecular understanding of electrical synapses. Proximity-based proteomics has revealed the diverse protein composition at electrical synapse sites, defining sub-synaptic compartments in neuronal circuits. Additionally, studies in zebrafish have shown that electrical synapses mediate embryonic hyperactivity prior to chemical synapse development, highlighting their role in early neural circuit function.[81][82] Despite these advances, key gaps persist in understanding electrical synapses' contributions to human cognition and their evolutionary history. The precise impact of electrical synapses on higher cognitive processes, such as learning and memory, remains unclear, with evidence only suggesting potential links to neurophysiological disruptions in disorders like schizophrenia, but lacking direct behavioral correlates in humans. Evolutionarily, electrical synapses appear to have arisen independently multiple times, driven by convergent evolution of unrelated proteins like connexins in chordates and innexins/pannexins in invertebrates, including ctenophores, raising questions about their ancestral roles in early neural-like systems.[83][84]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[neuroscience](/page/Neuroscience)/electrical-synapse