Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Membrane potential

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The large purple structure with an arrow represents a transmembrane potassium channel and the direction of net potassium movement.

Membrane potential (also transmembrane potential or membrane voltage) is the difference in electric potential between the interior and the exterior of a biological cell. It equals the interior potential minus the exterior potential. This is the energy (i.e. work) per charge which is required to move a (very small) positive charge at constant velocity across the cell membrane from the exterior to the interior. (If the charge is allowed to change velocity, the change of kinetic energy and production of radiation[1] must be taken into account.)

Typical values of membrane potential, normally given in units of millivolts and denoted as mV, range from −80 mV to −40 mV. For such typical negative membrane potentials, positive work is required to move a positive charge from the interior to the exterior. However, thermal kinetic energy allows ions to overcome the potential difference. For a selectively permeable membrane, this permits a net flow against the gradient. This is a kind of osmosis.

Description

[edit]All animal cells are surrounded by a membrane composed of a lipid bilayer with proteins embedded in it. The membrane serves both as an electrical insulator and as a diffusion barrier to the movement of ions. Transmembrane proteins, also known as ion transporter or ion pump proteins, actively push ions across the membrane and establish concentration gradients across the membrane, and ion channels allow ions to move across the membrane down those concentration gradients. Ion pumps and ion channels are electrically analogous to a set of capacitors and resistors inserted in the membrane, and therefore create a voltage between the two sides of the membrane; acting somewhat like a memristor.[2]

All plasma membranes have an electrical potential across them, with the inside usually negative with respect to the outside.[3] The membrane potential has two basic functions. First, it allows a cell to function as a battery, providing power to operate a variety of "molecular devices" embedded in the membrane.[4] Second, in electrically excitable cells such as neurons and muscle cells, it is used for transmitting signals between different parts of a cell.

Signals in neurons and muscle cells

[edit]Signals are generated in excitable cells by opening or closing of ion channels at one point in the membrane, producing a local change in the membrane potential. This change in the electric field can be quickly sensed by either adjacent or more distant ion channels in the membrane. Those ion channels can then open or close as a result of the potential change, reproducing the signal.

In non-excitable cells, and in excitable cells in their baseline states, the membrane potential is held at a relatively stable value, called the resting potential. For neurons, resting potential is defined as ranging from −80 to −70 millivolts; that is, the interior of a cell has a negative baseline voltage of a bit less than one-tenth of a volt. The opening and closing of ion channels can induce a departure from the resting potential. This is called a depolarization if the interior voltage becomes less negative (say from −70 mV to −60 mV), or a hyperpolarization if the interior voltage becomes more negative (say from −70 mV to −80 mV). In excitable cells, a sufficiently large depolarization can evoke an action potential, in which the membrane potential changes rapidly and significantly for a short time (on the order of 1 to 100 milliseconds), often reversing its polarity. Action potentials are generated by the activation of certain voltage-gated ion channels.

In neurons, the factors that influence the membrane potential are diverse. They include numerous types of ion channels, some of which are chemically gated and some of which are voltage-gated. Because voltage-gated ion channels are controlled by the membrane potential, while the membrane potential itself is influenced by these same ion channels, feedback loops that allow for complex temporal dynamics arise, including oscillations and regenerative events such as action potentials.[citation needed]

Ion concentration gradients

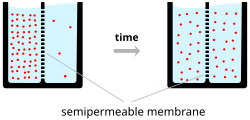

[edit]Differences in the concentrations of ions on opposite sides of a cellular membrane lead to a voltage called the membrane potential.[5]

Many ions have a concentration gradient across the membrane, including potassium (K+), which is at a high concentration inside and a low concentration outside the membrane. Sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions are at high concentrations in the extracellular region, and low concentrations in the intracellular regions. These concentration gradients provide the potential energy to drive the formation of the membrane potential. This voltage is established when the membrane has permeability to one or more ions.

In the simplest case, illustrated in the top diagram ("Ion concentration gradients"), if the membrane is selectively permeable to potassium, these positively charged ions can diffuse down the concentration gradient to the outside of the cell, leaving behind uncompensated negative charges. This separation of charges is what causes the membrane potential.

The system as a whole is electro-neutral. The uncompensated positive charges outside the cell, and the uncompensated negative charges inside the cell, physically line up on the membrane surface and attract each other across the lipid bilayer. Thus, the membrane potential is physically located only in the immediate vicinity of the membrane. It is the separation of these charges across the membrane that is the basis of the membrane voltage.

The top diagram is only an approximation of the ionic contributions to the membrane potential. Other ions including sodium, chloride, calcium, and others play a more minor role, even though they have strong concentration gradients, because they have more limited permeability than potassium.[citation needed]

Physical basis

[edit]The membrane potential in a cell derives ultimately from two factors: electrical force and diffusion. Electrical force arises from the mutual attraction between particles with opposite electrical charges (positive and negative) and the mutual repulsion between particles with the same type of charge (both positive or both negative). Diffusion arises from the statistical tendency of particles to redistribute from regions where they are highly concentrated to regions where the concentration is low.

Voltage

[edit]

Voltage, which is synonymous with difference in electrical potential, is the ability to drive an electric current across a resistance. Indeed, the simplest definition of a voltage is given by Ohm's law: V=IR, where V is voltage, I is current and R is resistance. If a voltage source such as a battery is placed in an electrical circuit, the higher the voltage of the source the greater the amount of current that it will drive across the available resistance. The functional significance of voltage lies only in potential differences between two points in a circuit. The idea of a voltage at a single point is meaningless. It is conventional in electronics to assign a voltage of zero to some arbitrarily chosen element of the circuit, and then assign voltages for other elements measured relative to that zero point. There is no significance in which element is chosen as the zero point—the function of a circuit depends only on the differences not on voltages per se. However, in most cases and by convention, the zero level is most often assigned to the portion of a circuit that is in contact with ground.

The same principle applies to voltage in cell biology. In electrically active tissue, the potential difference between any two points can be measured by inserting an electrode at each point, for example one inside and one outside the cell, and connecting both electrodes to the leads of what is in essence a specialized voltmeter. By convention, the zero potential value is assigned to the outside of the cell and the sign of the potential difference between the outside and the inside is determined by the potential of the inside relative to the outside zero.

In mathematical terms, the definition of voltage begins with the concept of an electric field E, a vector field assigning a magnitude and direction to each point in space. In many situations, the electric field is a conservative field, which means that it can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar function V, that is, E = −∇V. This scalar field V is referred to as the voltage distribution. The definition allows for an arbitrary constant of integration—this is why absolute values of voltage are not meaningful. In general, electric fields can be treated as conservative only if magnetic fields do not significantly influence them, but this condition usually applies well to biological tissue.

Because the electric field is the gradient of the voltage distribution, rapid changes in voltage within a small region imply a strong electric field; on the converse, if the voltage remains approximately the same over a large region, the electric fields in that region must be weak. A strong electric field, equivalent to a strong voltage gradient, implies that a strong force is exerted on any charged particles that lie within the region.

Ions and the forces driving their motion

[edit]

Electrical signals within biological organisms are, in general, driven by ions.[7] The most important cations for the action potential are sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+).[8] Both of these are monovalent cations that carry a single positive charge. Action potentials can also involve calcium (Ca2+),[9] which is a divalent cation that carries a double positive charge. The chloride anion (Cl−) plays a major role in the action potentials of some algae,[10] but plays a negligible role in the action potentials of most animals.[11]

Ions cross the cell membrane under two influences: diffusion and electric fields. A simple example wherein two solutions—A and B—are separated by a porous barrier illustrates that diffusion will ensure that they will eventually mix into equal solutions. This mixing occurs because of the difference in their concentrations. The region with high concentration will diffuse out toward the region with low concentration. To extend the example, let solution A have 30 sodium ions and 30 chloride ions. Also, let solution B have only 20 sodium ions and 20 chloride ions. Assuming the barrier allows both types of ions to travel through it, then a steady state will be reached whereby both solutions have 25 sodium ions and 25 chloride ions. If, however, the porous barrier is selective to which ions are let through, then diffusion alone will not determine the resulting solution. Returning to the previous example, let's now construct a barrier that is permeable only to sodium ions. Now, only sodium is allowed to diffuse cross the barrier from its higher concentration in solution A to the lower concentration in solution B. This will result in a greater accumulation of sodium ions than chloride ions in solution B and a lesser number of sodium ions than chloride ions in solution A.

This means that there is a net positive charge in solution B from the higher concentration of positively charged sodium ions than negatively charged chloride ions. Likewise, there is a net negative charge in solution A from the greater concentration of negative chloride ions than positive sodium ions. Since opposite charges attract and like charges repel, the ions are now also influenced by electrical fields as well as forces of diffusion. Therefore, positive sodium ions will be less likely to travel to the now-more-positive B solution and remain in the now-more-negative A solution. The point at which the forces of the electric fields completely counteract the force due to diffusion is called the equilibrium potential. At this point, the net flow of the specific ion (in this case sodium) is zero.

Plasma membranes

[edit]

Every cell is enclosed in a plasma membrane, which has the structure of a lipid bilayer with many types of large molecules embedded in it. Because it is made of lipid molecules, the plasma membrane intrinsically has a high electrical resistivity, in other words a low intrinsic permeability to ions. However, some of the molecules embedded in the membrane are capable either of actively transporting ions from one side of the membrane to the other or of providing channels through which they can move.[12]

In electrical terminology, the plasma membrane functions as a combined resistor and capacitor. Resistance arises from the fact that the membrane impedes the movement of charges across it. Capacitance arises from the fact that the lipid bilayer is so thin that an accumulation of charged particles on one side gives rise to an electrical force that pulls oppositely charged particles toward the other side. The capacitance of the membrane is relatively unaffected by the molecules that are embedded in it, so it has a more or less invariant value estimated at 2 μF/cm2 (the total capacitance of a patch of membrane is proportional to its area). The conductance of a pure lipid bilayer is so low, on the other hand, that in biological situations it is always dominated by the conductance of alternative pathways provided by embedded molecules. Thus, the capacitance of the membrane is more or less fixed, but the resistance is highly variable.

The thickness of a plasma membrane is estimated to be about 7–8 nanometers. Because the membrane is so thin, it does not take a very large transmembrane voltage to create a strong electric field within it. Typical membrane potentials in animal cells are on the order of 100 millivolts (that is, one tenth of a volt), but calculations show that this generates an electric field close to the maximum that the membrane can sustain—it has been calculated that a voltage difference much larger than 200 millivolts could cause dielectric breakdown, that is, arcing across the membrane.

Facilitated diffusion and transport

[edit]

The resistance of a pure lipid bilayer to the passage of ions across it is very high, but structures embedded in the membrane can greatly enhance ion movement, either actively or passively, via mechanisms called facilitated transport and facilitated diffusion. The two types of structure that play the largest roles are ion channels and ion pumps, both usually formed from assemblages of protein molecules. Ion channels provide passageways through which ions can move. In most cases, an ion channel is permeable only to specific types of ions (for example, sodium and potassium but not chloride or calcium), and sometimes the permeability varies depending on the direction of ion movement. Ion pumps, also known as ion transporters or carrier proteins, actively transport specific types of ions from one side of the membrane to the other, sometimes using energy derived from metabolic processes to do so.

Ion pumps

[edit]

Ion pumps are integral membrane proteins that carry out active transport, i.e., use cellular energy (ATP) to "pump" the ions against their concentration gradient.[13] Such ion pumps take in ions from one side of the membrane (decreasing its concentration there) and release them on the other side (increasing its concentration there).

The ion pump most relevant to the action potential is the sodium–potassium pump, which transports three sodium ions out of the cell and two potassium ions in.[14][15] As a consequence, the concentration of potassium ions K+ inside the neuron is roughly 30-fold larger than the outside concentration, whereas the sodium concentration outside is roughly five-fold larger than inside.[15][16][17] In a similar manner, other ions have different concentrations inside and outside the neuron, such as calcium, chloride and magnesium.[17]

If the numbers of each type of ion were equal, the sodium–potassium pump would be electrically neutral, but, because of the three-for-two exchange, it gives a net movement of one positive charge from intracellular to extracellular for each cycle, thereby contributing to a positive voltage difference. The pump has three effects: (1) it makes the sodium concentration high in the extracellular space and low in the intracellular space; (2) it makes the potassium concentration high in the intracellular space and low in the extracellular space; (3) it gives the intracellular space a negative voltage with respect to the extracellular space.

The sodium-potassium pump is relatively slow in operation. If a cell were initialized with equal concentrations of sodium and potassium everywhere, it would take hours for the pump to establish equilibrium. The pump operates constantly, but becomes progressively less efficient as the concentrations of sodium and potassium available for pumping are reduced.

Ion pumps influence the action potential only by establishing the relative ratio of intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations. The action potential involves mainly the opening and closing of ion channels not ion pumps. If the ion pumps are turned off by removing their energy source, or by adding an inhibitor such as ouabain, the axon can still fire hundreds of thousands of action potentials before their amplitudes begin to decay significantly.[13] In particular, ion pumps play no significant role in the repolarization of the membrane after an action potential.[8]

Another functionally important ion pump is the sodium-calcium exchanger. This pump operates in a conceptually similar way to the sodium-potassium pump, except that in each cycle it exchanges three Na+ from the extracellular space for one Ca++ from the intracellular space. Because the net flow of charge is inward, this pump runs "downhill", in effect, and therefore does not require any energy source except the membrane voltage. Its most important effect is to pump calcium outward—it also allows an inward flow of sodium, thereby counteracting the sodium-potassium pump, but, because overall sodium and potassium concentrations are much higher than calcium concentrations, this effect is relatively unimportant. The net result of the sodium-calcium exchanger is that in the resting state, intracellular calcium concentrations become very low.

Ion channels

[edit]

Ion channels are integral membrane proteins with a pore through which ions can travel between extracellular space and cell interior. Most channels are specific (selective) for one ion; for example, most potassium channels are characterized by 1000:1 selectivity ratio for potassium over sodium, though potassium and sodium ions have the same charge and differ only slightly in their radius. The channel pore is typically so small that ions must pass through it in single-file order.[19] Channel pores can be either open or closed for ion passage, although a number of channels demonstrate various sub-conductance levels. When a channel is open, ions permeate through the channel pore down the transmembrane concentration gradient for that particular ion. Rate of ionic flow through the channel, i.e. single-channel current amplitude, is determined by the maximum channel conductance and electrochemical driving force for that ion, which is the difference between the instantaneous value of the membrane potential and the value of the reversal potential.[20]

A channel may have several different states (corresponding to different conformations of the protein), but each such state is either open or closed. In general, closed states correspond either to a contraction of the pore—making it impassable to the ion—or to a separate part of the protein, stoppering the pore. For example, the voltage-dependent sodium channel undergoes inactivation, in which a portion of the protein swings into the pore, sealing it.[21] This inactivation shuts off the sodium current and plays a critical role in the action potential.

Ion channels can be classified by how they respond to their environment.[22] For example, the ion channels involved in the action potential are voltage-sensitive channels; they open and close in response to the voltage across the membrane. Ligand-gated channels form another important class; these ion channels open and close in response to the binding of a ligand molecule, such as a neurotransmitter. Other ion channels open and close with mechanical forces. Still other ion channels—such as those of sensory neurons—open and close in response to other stimuli, such as light, temperature or pressure.

Leakage channels

[edit]Leakage channels are the simplest type of ion channel, in that their permeability is more or less constant. The types of leakage channels that have the greatest significance in neurons are potassium and chloride channels. Even these are not perfectly constant in their properties: First, most of them are voltage-dependent in the sense that they conduct better in one direction than the other (in other words, they are rectifiers); second, some of them are capable of being shut off by chemical ligands even though they do not require ligands in order to operate.

Ligand-gated channels

[edit]

Ligand-gated ion channels are channels whose permeability is greatly increased when some type of chemical ligand binds to the protein structure. Animal cells contain hundreds, if not thousands, of types of these. A large subset function as neurotransmitter receptors—they occur at postsynaptic sites, and the chemical ligand that gates them is released by the presynaptic axon terminal. One example of this type is the AMPA receptor, a receptor for the neurotransmitter glutamate that when activated allows passage of sodium and potassium ions. Another example is the GABAA receptor, a receptor for the neurotransmitter GABA that when activated allows passage of chloride ions.

Neurotransmitter receptors are activated by ligands that appear in the extracellular area, but there are other types of ligand-gated channels that are controlled by interactions on the intracellular side.

Voltage-dependent channels

[edit]Voltage-gated ion channels, also known as voltage dependent ion channels, are channels whose permeability is influenced by the membrane potential. They form another very large group, with each member having a particular ion selectivity and a particular voltage dependence. Many are also time-dependent—in other words, they do not respond immediately to a voltage change but only after a delay.

One of the most important members of this group is a type of voltage-gated sodium channel that underlies action potentials—these are sometimes called Hodgkin-Huxley sodium channels because they were initially characterized by Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley in their Nobel Prize-winning studies of the physiology of the action potential. The channel is closed at the resting voltage level, but opens abruptly when the voltage exceeds a certain threshold, allowing a large influx of sodium ions that produces a very rapid change in the membrane potential. Recovery from an action potential is partly dependent on a type of voltage-gated potassium channel that is closed at the resting voltage level but opens as a consequence of the large voltage change produced during the action potential.

Reversal potential

[edit]The reversal potential (or equilibrium potential) of an ion is the value of transmembrane voltage at which diffusive and electrical forces counterbalance, so that there is no net ion flow across the membrane. This means that the transmembrane voltage exactly opposes the force of diffusion of the ion, such that the net current of the ion across the membrane is zero and unchanging. The reversal potential is important because it gives the voltage that acts on channels permeable to that ion—in other words, it gives the voltage that the ion concentration gradient generates when it acts as a battery.

The equilibrium potential of a particular ion is usually designated by the notation Eion.The equilibrium potential for any ion can be calculated using the Nernst equation.[23] For example, reversal potential for potassium ions will be as follows:

where

- Eeq,K+= equilibrium potential for potassium, measured in volts

- R = universal gas constant, equal to 8.314 joules·K−1·mol−1

- T = absolute temperature, measured in kelvins (= K = degrees Celsius + 273.15)

- z = number of elementary charges of the ion in question involved in the reaction

- F = Faraday constant, equal to 96,485 coulombs·mol−1 or J·V−1·mol−1

- [K+]o= extracellular concentration of potassium, measured in mol·m−3 or mmol·l−1

- [K+]i= intracellular concentration of potassium

Even if two different ions have the same charge (i.e., K+ and Na+), they can still have very different equilibrium potentials, provided their outside and/or inside concentrations differ. Take, for example, the equilibrium potentials of potassium and sodium in neurons. The potassium equilibrium potential EK is −84 mV with 5 mM potassium outside and 140 mM inside. On the other hand, the sodium equilibrium potential, ENa, is approximately +66 mV with approximately 12 mM sodium inside and 140 mM outside.[note 1]

Changes to membrane potential during development

[edit]A neuron's resting membrane potential actually changes during the development of an organism. In order for a neuron to eventually adopt its full adult function, its potential must be tightly regulated during development. As an organism progresses through development the resting membrane potential becomes more negative.[24] Glial cells are also differentiating and proliferating as development progresses in the brain.[25] The addition of these glial cells increases the organism's ability to regulate extracellular potassium. The drop in extracellular potassium can lead to a decrease in membrane potential of 35 mV.[26]

Cell excitability

[edit]Cell excitability is the change in membrane potential that is necessary for cellular responses in various tissues. Cell excitability is a property that is induced during early embryogenesis.[27] Excitability of a cell has also been defined as the ease with which a response may be triggered.[28] The resting and threshold potentials forms the basis of cell excitability and these processes are fundamental for the generation of graded and action potentials.

The most important regulators of cell excitability are the extracellular electrolyte concentrations (i.e. Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl−, Mg2+) and associated proteins. Important proteins that regulate cell excitability are voltage-gated ion channels, ion transporters (e.g. Na+/K+-ATPase, magnesium transporters, acid–base transporters), membrane receptors and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels.[29] For example, potassium channels and calcium-sensing receptors are important regulators of excitability in neurons, cardiac myocytes and many other excitable cells like astrocytes.[30] Calcium ion is also the most important second messenger in excitable cell signaling. Activation of synaptic receptors initiates long-lasting changes in neuronal excitability.[31] Thyroid, adrenal and other hormones also regulate cell excitability, for example, progesterone and estrogen modulate myometrial smooth muscle cell excitability.

Many cell types are considered to have an excitable membrane. Excitable cells are neurons, muscle (cardiac, skeletal, smooth), vascular endothelial cells, pericytes, juxtaglomerular cells, interstitial cells of Cajal, many types of epithelial cells (e.g. beta cells, alpha cells, delta cells, enteroendocrine cells, pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, pinealocytes), glial cells (e.g. astrocytes), mechanoreceptor cells (e.g. hair cells and Merkel cells), chemoreceptor cells (e.g. glomus cells, taste receptors), some plant cells and possibly immune cells.[32] Astrocytes display a form of non-electrical excitability based on intracellular calcium variations related to the expression of several receptors through which they can detect the synaptic signal. In neurons, there are different membrane properties in some portions of the cell, for example, dendritic excitability endows neurons with the capacity for coincidence detection of spatially separated inputs.[33]

Equivalent circuit

[edit]

Electrophysiologists model the effects of ionic concentration differences, ion channels, and membrane capacitance in terms of an equivalent circuit, which is intended to represent the electrical properties of a small patch of membrane. The equivalent circuit consists of a capacitor in parallel with four pathways each consisting of a battery in series with a variable conductance. The capacitance is determined by the properties of the lipid bilayer, and is taken to be fixed. Each of the four parallel pathways comes from one of the principal ions, sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium. The voltage of each ionic pathway is determined by the concentrations of the ion on each side of the membrane; see the Reversal potential section above. The conductance of each ionic pathway at any point in time is determined by the states of all the ion channels that are potentially permeable to that ion, including leakage channels, ligand-gated channels, and voltage-gated ion channels.

For fixed ion concentrations and fixed values of ion channel conductance, the equivalent circuit can be further reduced, using the Goldman equation as described below, to a circuit containing a capacitance in parallel with a battery and conductance. In electrical terms, this is a type of RC circuit (resistance-capacitance circuit), and its electrical properties are very simple. Starting from any initial state, the current flowing across either the conductance or the capacitance decays with an exponential time course, with a time constant of τ = RC, where C is the capacitance of the membrane patch, and R = 1/gnet is the net resistance. For realistic situations, the time constant usually lies in the 1–100 millisecond range. In most cases, changes in the conductance of ion channels occur on a faster time scale, so an RC circuit is not a good approximation; however, the differential equation used to model a membrane patch is commonly a modified version of the RC circuit equation.

Resting potential

[edit]When the membrane potential of a cell goes for a long period of time without changing significantly, it is referred to as a resting potential or resting voltage. This term is used for the membrane potential of non-excitable cells, but also for the membrane potential of excitable cells in the absence of excitation. In excitable cells, the other possible states are graded membrane potentials (of variable amplitude), and action potentials, which are large, all-or-nothing rises in membrane potential that usually follow a fixed time course. Excitable cells include neurons, muscle cells, and some secretory cells in glands. Even in other types of cells, however, the membrane voltage can undergo changes in response to environmental or intracellular stimuli. For example, depolarization of the plasma membrane appears to be an important step in programmed cell death.[34]

The interactions that generate the resting potential are modeled by the Goldman equation.[35] This is similar in form to the Nernst equation shown above, in that it is based on the charges of the ions in question, as well as the difference between their inside and outside concentrations. However, it also takes into consideration the relative permeability of the plasma membrane to each ion in question.

The three ions that appear in this equation are potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), and chloride (Cl−). Calcium is omitted, but can be added to deal with situations in which it plays a significant role.[36] Being an anion, the chloride terms are treated differently from the cation terms; the intracellular concentration is in the numerator, and the extracellular concentration in the denominator, which is reversed from the cation terms. Pi stands for the relative permeability of the ion type i.

In essence, the Goldman formula expresses the membrane potential as a weighted average of the reversal potentials for the individual ion types, weighted by permeability. (Although the membrane potential changes about 100 mV during an action potential, the concentrations of ions inside and outside the cell do not change significantly. They remain close to their respective concentrations when then membrane is at resting potential.) In most animal cells, the permeability to potassium is much higher in the resting state than the permeability to sodium. As a consequence, the resting potential is usually close to the potassium reversal potential.[37][38] The permeability to chloride can be high enough to be significant, but, unlike the other ions, chloride is not actively pumped, and therefore equilibrates at a reversal potential very close to the resting potential determined by the other ions.

Values of resting membrane potential in most animal cells usually vary between the potassium reversal potential (usually around −80 mV) and around −40 mV. The resting potential in excitable cells (capable of producing action potentials) is usually near −60 mV—more depolarized voltages would lead to spontaneous generation of action potentials. Immature or undifferentiated cells show highly variable values of resting voltage, usually significantly more positive than in differentiated cells.[39] In such cells, the resting potential value correlates with the degree of differentiation: undifferentiated cells in some cases may not show any transmembrane voltage difference at all.

Maintenance of the resting potential can be metabolically costly for a cell because of its requirement for active pumping of ions to counteract losses due to leakage channels. The cost is highest when the cell function requires an especially depolarized value of membrane voltage. For example, the resting potential in daylight-adapted blowfly (Calliphora vicina) photoreceptors can be as high as −30 mV.[40] This elevated membrane potential allows the cells to respond very rapidly to visual inputs; the cost is that maintenance of the resting potential may consume more than 20% of overall cellular ATP.[41]

On the other hand, the high resting potential in undifferentiated cells does not necessarily incur a high metabolic cost. This apparent paradox is resolved by examination of the origin of that resting potential. Little-differentiated cells are characterized by extremely high input resistance,[39] which implies that few leakage channels are present at this stage of cell life. As an apparent result, potassium permeability becomes similar to that for sodium ions, which places resting potential in-between the reversal potentials for sodium and potassium as discussed above. The reduced leakage currents also mean there is little need for active pumping in order to compensate, therefore low metabolic cost.

Graded potentials

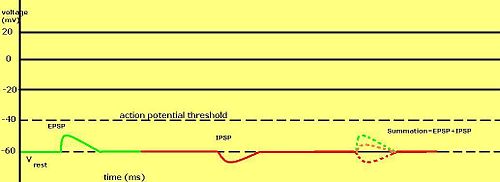

[edit]As explained above, the potential at any point in a cell's membrane is determined by the ion concentration differences between the intracellular and extracellular areas, and by the permeability of the membrane to each type of ion. The ion concentrations do not normally change very quickly (with the exception of Ca2+, where the baseline intracellular concentration is so low that even a small influx may increase it by orders of magnitude), but the permeabilities of the ions can change in a fraction of a millisecond, as a result of activation of ligand-gated ion channels. The change in membrane potential can be either large or small, depending on how many ion channels are activated and what type they are, and can be either long or short, depending on the lengths of time that the channels remain open. Changes of this type are referred to as graded potentials, in contrast to action potentials, which have a fixed amplitude and time course.

As can be derived from the Goldman equation shown above, the effect of increasing the permeability of a membrane to a particular type of ion shifts the membrane potential toward the reversal potential for that ion. Thus, opening Na+ channels shifts the membrane potential toward the Na+ reversal potential, which is usually around +100 mV. Likewise, opening K+ channels shifts the membrane potential toward about −90 mV, and opening Cl− channels shifts it toward about −70 mV (resting potential of most membranes). Thus, Na+ channels shift the membrane potential in a positive direction, K+ channels shift it in a negative direction (except when the membrane is hyperpolarized to a value more negative than the K+ reversal potential), and Cl− channels tend to shift it towards the resting potential.

Graded membrane potentials are particularly important in neurons, where they are produced by synapses—a temporary change in membrane potential produced by activation of a synapse by a single graded or action potential is called a postsynaptic potential. Neurotransmitters that act to open Na+ channels typically cause the membrane potential to become more positive, while neurotransmitters that activate K+ channels typically cause it to become more negative; those that inhibit these channels tend to have the opposite effect.

Whether a postsynaptic potential is considered excitatory or inhibitory depends on the reversal potential for the ions of that current, and the threshold for the cell to fire an action potential (around −50 mV). A postsynaptic current with a reversal potential above threshold, such as a typical Na+ current, is considered excitatory. A current with a reversal potential below threshold, such as a typical K+ current, is considered inhibitory. A current with a reversal potential above the resting potential, but below threshold, will not by itself elicit action potentials, but will produce subthreshold membrane potential oscillations. Thus, neurotransmitters that act to open Na+ channels produce excitatory postsynaptic potentials, or EPSPs, whereas neurotransmitters that act to open K+ or Cl− channels typically produce inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, or IPSPs. When multiple types of channels are open within the same time period, their postsynaptic potentials summate (are added together).

Other values

[edit]From the viewpoint of biophysics, the resting membrane potential is merely the membrane potential that results from the membrane permeabilities that predominate when the cell is resting. The above equation of weighted averages always applies, but the following approach may be more easily visualized. At any given moment, there are two factors for an ion that determine how much influence that ion will have over the membrane potential of a cell:

- That ion's driving force

- That ion's permeability

If the driving force is high, then the ion is being "pushed" across the membrane. If the permeability is high, it will be easier for the ion to diffuse across the membrane.

- Driving force is the net electrical force available to move that ion across the membrane. It is calculated as the difference between the voltage that the ion "wants" to be at (its equilibrium potential) and the actual membrane potential (Em). So, in formal terms, the driving force for an ion = Em − Eion

- For example, at our earlier calculated resting potential of −73 mV, the driving force on potassium is 7 mV : (−73 mV) − (−80 mV) = 7 mV. The driving force on sodium would be (−73 mV) − (60 mV) = −133 mV.

- Permeability is a measure of how easily an ion can cross the membrane. It is normally measured as the (electrical) conductance and the unit, siemens, corresponds to 1 C·s−1·V−1, that is one coulomb per second per volt of potential.

So, in a resting membrane, while the driving force for potassium is low, its permeability is very high. Sodium has a huge driving force but almost no resting permeability. In this case, potassium carries about 20 times more current than sodium, and thus has 20 times more influence over Em than does sodium.

However, consider another case—the peak of the action potential. Here, permeability to Na is high and K permeability is relatively low. Thus, the membrane moves to near ENa and far from EK.

The more ions are permeant the more complicated it becomes to predict the membrane potential. However, this can be done using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation or the weighted means equation. By plugging in the concentration gradients and the permeabilities of the ions at any instant in time, one can determine the membrane potential at that moment. What the GHK equations means is that, at any time, the value of the membrane potential will be a weighted average of the equilibrium potentials of all permeant ions. The "weighting" is the ions relative permeability across the membrane.

Effects and implications

[edit]While cells expend energy to transport ions and establish a transmembrane potential, they use this potential in turn to transport other ions and metabolites such as sugar. The transmembrane potential of the mitochondria drives the production of ATP, which is the common currency of biological energy.

Cells may draw on the energy they store in the resting potential to drive action potentials or other forms of excitation. These changes in the membrane potential enable communication with other cells (as with action potentials) or initiate changes inside the cell, which happens in an egg when it is fertilized by a sperm.

Changes in the dielectric properties of plasma membrane may act as hallmark of underlying conditions such as diabetes and dyslipidemia.[42]

In neuronal cells, an action potential begins with a rush of sodium ions into the cell through sodium channels, resulting in depolarization, while recovery involves an outward rush of potassium through potassium channels. Both of these fluxes occur by passive diffusion.

A dose of salt may trigger the still-working neurons of a fresh cut of meat into firing, causing muscle spasms.[43][44][45][46][47]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The signs of ENa and EK are opposite. This is because the concentration gradient for potassium is directed out of the cell, while the concentration gradient for sodium is directed into the cell. Membrane potentials are defined relative to the exterior of the cell; thus, a potential of −70 mV implies that the interior of the cell is negative relative to the exterior.

References

[edit]- ^ Bohm, David (1989) [1951]. Quantum Theory (Dover reprint ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-486-65969-5. OCLC 1103789975.

- ^ Nabil, Amr; Kumar, T. Nandha; Almurib, Haider Abbas F. (December 2022). "Mott Memristors and Neuronal Ion Channels: A Qualitative Analysis". IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems. 12 (4): 762–773. Bibcode:2022IJEST..12..762N. doi:10.1109/JETCAS.2022.3221735. ISSN 2156-3365.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Morgan, David; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2014-11-18). Molecular Biology of the Cell (Sixth ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2. OCLC 887605755.

- ^ Abdul Kadir, Lina; Stacey, Michael; Barrett-Jolley, Richard (2018). "Emerging Roles of the Membrane Potential: Action Beyond the Action Potential". Frontiers in Physiology. 9 1661. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01661. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 6258788. PMID 30519193.

- ^ Jaffe, Lionel F.; Nuccitelli, Richard (1977). "Electrical Controls of Development" (PDF). Annual Review of Biophysics and Bioengineering. 6 (1): 445–476. doi:10.1146/annurev.bb.06.060177.002305. PMID 326151. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Campbell Biology, 6th edition

- ^ Johnston and Wu, p. 9.

- ^ a b Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, pp. 140–41.

- ^ Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Mummert H, Gradmann D (1991). "Action potentials in Acetabularia: measurement and simulation of voltage-gated fluxes". Journal of Membrane Biology. 124 (3): 265–73. doi:10.1007/BF01994359. PMID 1664861. S2CID 22063907.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, p. 483.

- ^ Lieb WR, Stein WD (1986). "Chapter 2. Simple Diffusion across the Membrane Barrier". Transport and Diffusion across Cell Membranes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 69–112. ISBN 978-0-12-664661-0.

- ^ a b Hodgkin AL, Keynes RD (1955). "Active transport of cations in giant axons from Sepia and Loligo". J. Physiol. 128 (1): 28–60. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005290. PMC 1365754. PMID 14368574.

- ^ Caldwell PC, Hodgkin AL, Keynes RD, Shaw TI (1960). "The effects of injecting energy-rich phosphate compounds on the active transport of ions in the giant axons of Loligo". J. Physiol. 152 (3): 561–90. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006509. PMC 1363339. PMID 13806926.

- ^ a b Gagnon KB, Delpire E (2021). "Sodium Transporters in Human Health and Disease (Figure 2)". Frontiers in Physiology. 11 588664. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.588664. PMC 7947867. PMID 33716756.

- ^ Steinbach HB, Spiegelman S (1943). "The sodium and potassium balance in squid nerve axoplasm". J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 22 (2): 187–96. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030220209.

- ^ a b Hodgkin AL (1951). "The ionic basis of electrical activity in nerve and muscle". Biol. Rev. 26 (4): 339–409. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1951.tb01204.x. S2CID 86282580.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 83rd edition, ISBN 0-8493-0483-0, pp. 12–14 to 12–16.

- ^ Eisenman G (1961). "On the elementary atomic origin of equilibrium ionic specificity". In A Kleinzeller; A Kotyk (eds.). Symposium on Membrane Transport and Metabolism. New York: Academic Press. pp. 163–79.Eisenman G (1965). "Some elementary factors involved in specific ion permeation". Proc. 23rd Int. Congr. Physiol. Sci., Tokyo. Amsterdam: Excerta Med. Found. pp. 489–506.

* Diamond JM, Wright EM (1969). "Biological membranes: the physical basis of ion and nonekectrolyte selectivity". Annual Review of Physiology. 31: 581–646. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.31.030169.003053. PMID 4885777. - ^ Junge, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Cai SQ, Li W, Sesti F (2007). "Multiple modes of a-type potassium current regulation". Curr. Pharm. Des. 13 (31): 3178–84. doi:10.2174/138161207782341286. PMID 18045167.

- ^ Goldin AL (2007). "Neuronal Channels and Receptors". In Waxman SG (ed.). Molecular Neurology. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 43–58. ISBN 978-0-12-369509-3.

- ^ Purves et al., pp. 28–32; Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, pp. 133–134; Schmidt-Nielsen, pp. 478–480, 596–597; Junge, pp. 33–35

- ^ Sanes, Dan H.; Takács, Catherine (1993-06-01). "Activity-dependent Refinement of Inhibitory Connections". European Journal of Neuroscience. 5 (6): 570–574. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00522.x. ISSN 1460-9568. PMID 8261131. S2CID 30714579.

- ^ KOFUJI, P.; NEWMAN, E. A. (2004-01-01). "Potassium buffering in the central nervous system". Neuroscience. 129 (4): 1045–1056. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.008. ISSN 0306-4522. PMC 2322935. PMID 15561419.

- ^ Sanes, Dan H.; Reh, Thomas A (2012-01-01). Development of the nervous system (Third ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 211–214. ISBN 978-0-08-092320-8. OCLC 762720374.

- ^ Tosti, Elisabetta (2010-06-28). "Dynamic roles of ion currents in early development". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 77 (10): 856–867. doi:10.1002/mrd.21215. ISSN 1040-452X. PMID 20586098. S2CID 38314187.

- ^ Boyet, M.R.; Jewell, B.R. (1981). "Analysis of the effects of changes in rate and rhythm upon electrical activity in the heart". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 36 (1): 1–52. doi:10.1016/0079-6107(81)90003-1. ISSN 0079-6107. PMID 7001542.

- ^ Spinelli, Valentina; Sartiani, Laura; Mugelli, Alessandro; Romanelli, Maria Novella; Cerbai, Elisabetta (2018). "Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels: pathophysiological, developmental, and pharmacological insights into their function in cellular excitability". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 96 (10): 977–984. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2018-0115. hdl:1807/90084. ISSN 0008-4212. PMID 29969572. S2CID 49679747.

- ^ Jones, Brian L.; Smith, Stephen M. (2016-03-30). "Calcium-Sensing Receptor: A Key Target for Extracellular Calcium Signaling in Neurons". Frontiers in Physiology. 7: 116. doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00116. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4811949. PMID 27065884.

- ^ Debanne, Dominique; Inglebert, Yanis; Russier, Michaël (2019). "Plasticity of intrinsic neuronal excitability" (PDF). Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 54: 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2018.09.001. PMID 30243042. S2CID 52812190.

- ^ Davenport, Bennett; Li, Yuan; Heizer, Justin W.; Schmitz, Carsten; Perraud, Anne-Laure (2015-07-23). "Signature Channels of Excitability no More: L-Type Channels in Immune Cells". Frontiers in Immunology. 6: 375. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00375. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4512153. PMID 26257741.

- ^ Sakmann, Bert (2017-04-21). "From single cells and single columns to cortical networks: dendritic excitability, coincidence detection and synaptic transmission in brain slices and brains". Experimental Physiology. 102 (5): 489–521. doi:10.1113/ep085776. ISSN 0958-0670. PMC 5435930. PMID 28139019.

- ^ Franco R, Bortner CD, Cidlowski JA (January 2006). "Potential roles of electrogenic ion transport and plasma membrane depolarization in apoptosis". J. Membr. Biol. 209 (1): 43–58. doi:10.1007/s00232-005-0837-5. PMID 16685600. S2CID 849895.

- ^ Purves et al., pp. 32–33; Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, pp. 138–140; Schmidt-Nielsen, pp. 480; Junge, pp. 35–37

- ^ Spangler SG (1972). "Expansion of the constant field equation to include both divalent and monovalent ions". Alabama Journal of Medical Sciences. 9 (2): 218–23. PMID 5045041.

- ^ Purves et al., p. 34; Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, p. 134; Schmidt-Nielsen, pp. 478–480.

- ^ Purves et al., pp. 33–36; Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, p. 131.

- ^ a b Magnuson DS, Morassutti DJ, Staines WA, McBurney MW, Marshall KC (Jan 14, 1995). "In vivo electrophysiological maturation of neurons derived from a multipotent precursor (embryonal carcinoma) cell line". Developmental Brain Research. 84 (1): 130–41. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(94)00166-W. PMID 7720212.

- ^ Juusola M, Kouvalainen E, Järvilehto M, Weckström M (Sep 1994). "Contrast gain, signal-to-noise ratio, and linearity in light-adapted blowfly photoreceptors". J Gen Physiol. 104 (3): 593–621. doi:10.1085/jgp.104.3.593. PMC 2229225. PMID 7807062.

- ^ Laughlin SB, de Ruyter van Steveninck RR, Anderson JC (May 1998). "The metabolic cost of neural information". Nat. Neurosci. 1 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1038/236. PMID 10195106. S2CID 204995437.

- ^ Ghoshal K, et al. (December 2017). "Dielectric properties of plasma membrane: A signature for dyslipidemia in diabetes mellitus". Arch Biochem Biophys. 635: 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2017.10.002. PMID 29029878.

- ^ Wilcox, Christie (July 28, 2011). "Instant Zombie - Just Add Salt". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Crew, Bec (3 July 2015). "Watch: Slab of Raw Beef Appears to Pulse After Being Brought Home From Butcher". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "女子切". legal.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Gibson, Gray (January 11, 2023). "Common condiment causes freshly cut meat to pulsate, horrifying Twitter". Newshub. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Cost, Ben (10 January 2023). "Beef twerky: internet horrified over video of fresh meat 'spasming'". nypost.com. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Alberts et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Publishing; 4th Bk&Cdr edition (March, 2002). ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. Undergraduate level.

- Guyton, Arthur C., John E. Hall. Textbook of medical physiology. W.B. Saunders Company; 10th edition (August 15, 2000). ISBN 0-7216-8677-X. Undergraduate level.

- Hille, B. Ionic Channel of Excitable Membranes Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, USA; 1st Edition, 1984. ISBN 0-87893-322-0

- Nicholls, J.G., Martin, A.R. and Wallace, B.G. From Neuron to Brain Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sunderland, MA, USA 3rd Edition, 1992. ISBN 0-87893-580-0

- Ove-Sten Knudsen. Biological Membranes: Theory of Transport, Potentials and Electric Impulses. Cambridge University Press (September 26, 2002). ISBN 0-521-81018-3. Graduate level.

- National Medical Series for Independent Study. Physiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, PA, USA 4th Edition, 2001. ISBN 0-683-30603-0

External links

[edit]Membrane potential

View on GrokipediaOverview and Significance

Definition and basic principles

Membrane potential refers to the electrical potential difference, or voltage, across the plasma membrane of a biological cell, typically ranging from -40 to -90 millivolts (mV) in living cells, with the intracellular side negative relative to the extracellular side.[4][1] This voltage arises primarily from the unequal distribution of charged ions, such as potassium (K⁺), sodium (Na⁺), chloride (Cl⁻), and others, across the lipid bilayer, which acts as a barrier to free ion movement.[4] The resulting charge separation creates an electrochemical gradient that is essential for cellular function, though the exact value varies by cell type, with neurons often around -70 mV and muscle cells near -90 mV.[1][5] At its core, the membrane potential stems from the semi-permeable nature of the plasma membrane, which permits selective ion passage while restricting others, leading to a net accumulation of negative charges inside the cell.[5] In most eukaryotic cells, the interior maintains a negative potential due to higher concentrations of negatively charged proteins and organic anions that cannot cross the membrane, coupled with the efflux of cations like K⁺ through leak channels.[4] This charge imbalance is dynamically balanced by the membrane's low but nonzero permeability to various ions, preventing complete equalization while sustaining the potential.[5] The potential represents a steady-state condition in resting cells, where passive ion diffusion is counteracted by active processes to preserve ion gradients.[1] The foundational understanding of membrane potential traces back to Julius Bernstein's 1902 membrane theory, which proposed that the resting potential results from the cell membrane's selective permeability to K⁺ ions, allowing their diffusion to dominate and establish a negative interior.[6] Bernstein's hypothesis, based on early electrical measurements of nerve fibers, suggested that excitation temporarily disrupts this selectivity, equalizing the potential.[7] This theory laid the groundwork for modern biophysics, later refined by observations of other ions' roles.[6] Membrane potential is quantified in millivolts (mV), a unit reflecting the small scale of these bioelectric differences, and is conventionally measured with the extracellular fluid as the reference point at 0 mV.[8] Intracellular recordings use fine-tipped microelectrodes inserted into the cell, comparing the potential to an extracellular reference electrode to yield the transmembrane voltage.[2] This technique, pioneered in the mid-20th century, confirms the negative intracellular values typical of healthy cells.[9]Biological roles in cells

In excitable cells such as neurons and muscle cells, the membrane potential plays a central role in enabling action potentials that propagate electrical signals over long distances. This process is essential for rapid communication within the nervous system and coordinated muscle activity. For instance, in neurons, the resting membrane potential of approximately -60 mV sets the stage for depolarization upon stimulus, leading to action potentials that travel along axons to synaptic terminals, where they trigger neurotransmitter release for synaptic transmission.[10] Similarly, in cardiac muscle cells, action potentials initiate contraction by propagating through the myocardium, with a prolonged plateau phase allowing calcium influx that couples electrical excitation to mechanical force generation, ensuring synchronized heartbeats.[11] In non-excitable cells, the membrane potential maintains cellular homeostasis by regulating ion transport, cell volume, and secretory processes. It influences the driving force for ion fluxes across the membrane, which is critical for secondary active transport and osmotic balance. For example, in epithelial cells, the membrane potential, modulated by polarity axes and transporters like the Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter (NKCC), directs chloride and water movement to control volume and support vectorial transport in tissues such as glandular structures.[12] This regulation extends to secretion, where hyperpolarization enhances calcium signaling to facilitate processes like insulin release in pancreatic β-cells, and volume control under osmotic stress in chondrocytes via specific ion channels.[13] The membrane potential exhibits remarkable evolutionary conservation across prokaryotes and eukaryotes, underscoring its fundamental role in energy coupling and cellular function. In prokaryotes, it forms part of the proton motive force across the plasma membrane, driving ATP synthesis through chemiosmosis. This bioenergetic mechanism persisted in eukaryotes, where the membrane potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane sustains oxidative phosphorylation, highlighting its ancient origins and adaptation for diverse physiological demands from basic metabolism to complex signaling.Biophysical Foundations

Ionic concentration gradients

In biological cells, particularly neurons and muscle cells, the plasma membrane maintains steep concentration gradients for key ions, which are essential for generating membrane potentials. The primary ions involved are sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), chloride (Cl⁻), and calcium (Ca²⁺). Typically, in mammalian neurons, intracellular K⁺ concentration is high at approximately 140–150 mM, while extracellular K⁺ is low at 4–5 mM; intracellular Na⁺ is low at 10–15 mM compared to extracellular levels of 140–145 mM; intracellular Cl⁻ is around 5–10 mM versus 110–120 mM extracellularly; and intracellular Ca²⁺ is extremely low at about 100 nM (0.0001 mM), in contrast to 1.5–2 mM extracellularly.[1][14][15] These gradients are established and maintained primarily through active transport mechanisms, such as the sodium-potassium ATPase (Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase) pump, which hydrolyzes ATP to export three Na⁺ ions out of the cell and import two K⁺ ions, thereby creating and sustaining the opposing Na⁺ and K⁺ distributions against their concentration gradients.[16] The pump's electrogenic activity also contributes a small direct negative charge to the interior. Selective permeability of the membrane, which favors K⁺ efflux over Na⁺ influx at rest due to higher K⁺ channel conductance, further stabilizes these imbalances.[16] For anions like Cl⁻, gradients often arise passively, influenced by the membrane's low permeability to Cl⁻ and the overall electrochemical environment. Ca²⁺ gradients are upheld by additional active transporters, such as the plasma membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase (PMCA), which extrudes Ca²⁺ using ATP.[1] A key factor in these ionic asymmetries is the Donnan equilibrium, arising from the presence of large, impermeant negatively charged macromolecules inside the cell, such as proteins and organic phosphates, which cannot cross the membrane. These impermeant anions (A⁻) attract diffusible cations like K⁺ into the cell while repelling anions like Cl⁻, resulting in an unequal distribution of permeant ions across the membrane and contributing to the negative intracellular charge even in the absence of active transport.[17] In Donnan equilibrium, the product of permeant cation and anion concentrations inside the cell equals that outside, but the fixed negative charges from proteins ensure a net negative potential inside, typically on the order of -4 to -10 mV in simplified models, though active processes amplify this in living cells.[18] Intracellular ion concentrations are quantified using ion-sensitive microelectrodes, which are glass micropipettes filled with ion-selective liquid ion exchangers or solid-state sensors embedded in a reference electrolyte, allowing direct impalement of cells to measure ion activities with high spatial resolution.[19] These double-barreled or multi-barreled electrodes simultaneously record membrane potential and ion-specific potentials, enabling calculation of absolute concentrations via the Nernst relationship, with sensitivities down to micromolar levels for ions like Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺.[20] Such techniques have been pivotal in verifying gradients in various cell types, including neurons and muscle fibers.[21]| Ion | Intracellular (mM) | Extracellular (mM) |

|---|---|---|

| K⁺ | 140–150 | 4–5 |

| Na⁺ | 10–15 | 140–145 |

| Cl⁻ | 5–10 | 110–120 |

| Ca²⁺ | 0.0001 (100 nM) | 1.5–2 |

Driving forces on ions

The movement of ions across biological membranes is primarily driven by two distinct forces: the chemical driving force and the electrical driving force. The chemical driving force originates from the concentration gradient established across the membrane, compelling ions to diffuse passively from areas of higher concentration to areas of lower concentration until equilibrium is reached. This process reflects the entropic drive to homogenize solute distributions and is a direct consequence of Fick's laws of diffusion applied to ionic species.[22] The electrical driving force, in contrast, arises from the electrostatic potential difference, or membrane potential, generated by the uneven distribution of charged particles across the lipid bilayer. This voltage influences the motion of ions based on their charge: cations are pulled toward the more negative side of the membrane and repelled from the positive side, whereas anions move in the opposite direction. In most eukaryotic cells, the intracellular environment maintains a negative potential relative to the extracellular space, typically ranging from -20 mV to -200 mV, which exerts a significant attractive force on cations entering the cell.[22][8] Together, these forces constitute the electrochemical gradient, which provides the net driving force dictating the direction and rate of ion translocation when permeability allows. The electrochemical gradient integrates both diffusive and electrostatic components, with the overall force on an ion determined by how the prevailing membrane potential deviates from the balance point specific to that ion species. For instance, in neurons, the steep extracellular-to-intracellular gradient for sodium ions aligns both chemical and electrical forces to favor influx, while for potassium, they promote efflux.[22][23] Equilibrium for a given ion occurs precisely when the chemical driving force is counterbalanced by the electrical driving force, yielding zero net flux across the membrane. At this state, the membrane potential matches the ion's individual equilibrium potential, where the energy from concentration differences exactly offsets the electrostatic work required for charge separation. This balance, first conceptualized by Walther Nernst in his 1889 work on ion diffusion potentials, underscores the thermodynamic foundation of selective ion permeation in cellular physiology.[22][24]Plasma membrane structure and permeability

The plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells is primarily composed of a phospholipid bilayer, formed by amphipathic phospholipid molecules arranged with hydrophilic phosphate heads facing the aqueous environments on both sides and hydrophobic fatty acid tails sequestered in the core. This structure creates a hydrophobic barrier approximately 3-4 nm thick that is highly impermeable to charged ions and polar molecules, as the nonpolar interior repels hydrophilic solutes, preventing their passive diffusion across the membrane.[25] The bilayer's selective permeability arises from the amphipathic nature of phospholipids, allowing small nonpolar molecules such as oxygen and carbon dioxide to diffuse freely through the lipid core, while restricting larger polar or charged species.[26] Quantitative assessments of membrane permeability reveal stark differences for ions; for instance, the permeability coefficient for potassium ions (P_K) is significantly higher than for sodium ions (P_Na), with typical ratios in neuronal membranes around 1:0.04 at rest, reflecting the bilayer's intrinsic bias toward univalent cations but still orders of magnitude lower than for nonpolar solutes. This low ionic permeability, on the order of 10^{-12} to 10^{-14} cm/s for most ions without protein assistance, ensures that the membrane maintains electrochemical gradients essential for cellular functions.[27] Seminal electrophysiological studies on squid giant axons established these relative coefficients, underscoring the bilayer's role as a selective barrier. Embedded within the phospholipid bilayer are integral membrane proteins, including ion channels and transporters, which provide aqueous pores and facilitate selective ion permeation that the lipid barrier alone cannot support. According to the fluid mosaic model proposed by Singer and Nicolson, these proteins are dynamically inserted into the fluid lipid matrix, enabling regulated pathways for ions while preserving the overall impermeability of the unoccupied bilayer regions.[28] Without such proteins, ion flux would be negligible, highlighting their critical role in bridging the permeability gap created by the hydrophobic core.[22] Membrane permeability is modulated by environmental and compositional factors that influence bilayer fluidity. Elevated temperatures increase the kinetic energy of phospholipid tails, enhancing membrane fluidity and thereby elevating permeability to solutes, including ions, by facilitating transient defects in the bilayer structure. Conversely, cholesterol, a key sterol component comprising up to 50% of lipids in some animal cell membranes, intercalates between phospholipids to moderate fluidity: at high temperatures, it restricts chain motion to prevent excessive disorder, while at low temperatures, it disrupts packing to avoid gel-phase rigidity, thus stabilizing permeability across physiological ranges.[25] These effects ensure adaptive responses to thermal variations without compromising the barrier function.[29]Mechanisms of Ion Movement

Passive transport through channels

Passive transport through channels involves the movement of ions across the cell membrane driven solely by their electrochemical gradients, without requiring energy expenditure. These channels are integral membrane proteins that form selective pores, allowing ions such as Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, and Cl⁻ to pass at rates up to 10⁸ ions per second, vastly exceeding the diffusion rates through the lipid bilayer alone. This process, a form of facilitated diffusion, is crucial for maintaining ion balances and contributing to the baseline electrical properties of the membrane.[22] Leak channels, which are constitutively open and do not respond to stimuli, provide a continuous pathway for ion flux under resting conditions. Potassium leak channels, for example, are highly selective for K⁺ and predominate in many excitable and non-excitable cells, permitting a steady outward movement of K⁺ ions due to the intracellular K⁺ concentration gradient. This baseline permeability to K⁺ is essential for setting the membrane's resting conductance and preventing excessive depolarization from minor ion leaks. Other leak channels, such as those for Na⁺, allow limited inward flux, but their conductance is typically much lower than that of K⁺ channels.[1][30] In facilitated diffusion via these channels, ions traverse the membrane passively along their concentration and electrical gradients, with selectivity determined by the channel's pore structure, such as the selectivity filter in K⁺ channels that discriminates against Na⁺ by over 10,000-fold. The net ion flux through such channels is determined by permeability and the electrochemical driving force, combining the chemical concentration gradient and electrical potential difference.[31][22] The high K⁺ permeability imparted by leak channels ensures that the membrane potential remains close to the K⁺ equilibrium value, sustaining the typical negative intracellular charge of -60 to -80 mV in most cells.[31][22]Active transport via pumps

Active transport via pumps refers to energy-dependent processes that move ions across the cell membrane against their electrochemical gradients, thereby establishing and maintaining the ionic concentration differences crucial for membrane potential. These pumps utilize ATP as an energy source to drive ion translocation, counteracting the tendency of ions to leak passively and ensuring cellular homeostasis. In particular, they contribute to the asymmetry of ion distributions, such as higher intracellular potassium and lower intracellular sodium, which underpin the negative resting membrane potential in most cells.[16] The primary pump responsible for this in animal cells is the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, also known as the sodium-potassium pump, which actively extrudes three sodium ions (Na⁺) from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space while importing two potassium ions (K⁺) into the cell for each molecule of ATP hydrolyzed. This 3:2 stoichiometry makes the pump electrogenic, generating a net outward movement of positive charge that directly hyperpolarizes the membrane by approximately -10 mV, in addition to sustaining the Na⁺ and K⁺ gradients essential for the overall membrane potential. The Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase is ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells and plays a central role in osmotic balance and excitability, with its activity accounting for a significant portion of cellular ATP consumption under resting conditions.[16][32][33] Other notable pumps include the plasma membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase (PMCA), which extrudes calcium ions (Ca²⁺) from the cytosol to maintain low intracellular Ca²⁺ levels, thereby regulating signaling pathways that influence membrane potential indirectly through ion homeostasis. PMCA isoforms, regulated by calmodulin, are critical in excitable cells like neurons and muscle fibers, where they prevent Ca²⁺ overload that could depolarize the membrane. In specific cell types, such as plant cells or fungal cells, H⁺-ATPases pump protons (H⁺) out of the cytoplasm to acidify the extracellular space and generate a membrane potential that drives secondary ion uptake. Additionally, in gastric parietal cells of mammals, H⁺/K⁺-ATPase facilitates acid secretion by exchanging H⁺ for K⁺, contributing to localized pH gradients that affect membrane potential in those compartments.[34][35][36] The energy for these pumps derives from the hydrolysis of ATP, which binds to the pump protein and induces conformational changes that alternately expose ion-binding sites to the intracellular or extracellular side of the membrane. This cycle involves phosphorylation of the pump by ATP, which promotes a high-affinity state for intracellular ions, followed by dephosphorylation that releases ions extracellularly and resets the pump. Structural studies of P-type ATPases, including Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, reveal distinct E1 (ion-bound, inward-facing) and E2 (outward-facing) conformations driven by these ATP-dependent transitions, ensuring unidirectional transport against gradients.[37][38] By continuously operating to oppose passive ion diffusion through leaks, these pumps sustain the steep electrochemical gradients required for membrane potential, preventing dissipation that would equalize intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations over time. In neurons, for instance, Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity restores gradients after action potentials, while in non-excitable cells, it maintains volume and pH stability; inhibition of pumps leads to gradient collapse and loss of potential within minutes. This homeostatic function underscores their indispensability for cellular function across diverse organisms.[39][40]Gated ion channels

Gated ion channels are specialized proteins embedded in the cell membrane that regulate ion flow in response to specific stimuli, enabling transient and controlled changes in membrane potential essential for cellular signaling. Unlike constitutively open channels, gated channels exist in closed, open, or inactivated states, transitioning between them through stimulus-dependent mechanisms that allow rapid depolarization or repolarization. These channels are critical for processes such as synaptic transmission and nerve impulse propagation, where precise temporal control of ion permeability is required.[41] Ligand-gated ion channels open upon binding of extracellular ligands, such as neurotransmitters, to their receptor sites, facilitating ion influx or efflux that alters membrane potential. A prominent example is the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), a pentameric ligand-gated channel found at neuromuscular junctions and in the central nervous system. Binding of acetylcholine to the extracellular domain of nAChR induces a conformational change that opens the central pore, permitting Na⁺ influx (and some K⁺ efflux), which generates excitatory postsynaptic potentials and contributes to muscle contraction or neuronal excitation. The nAChR superfamily, including serotonin and GABA receptors, shares a conserved cysteine-loop structure that couples ligand binding to channel gating, with permeability ratios favoring cations in nicotinic subtypes.[42] Voltage-gated ion channels, in contrast, respond to alterations in transmembrane voltage, opening or closing based on the membrane's electrical state to drive dynamic potential shifts. Voltage-gated sodium channels (Naᵥ) activate rapidly upon depolarization, allowing Na⁺ entry that amplifies the signal and initiates action potentials in excitable cells like neurons and myocytes. Following activation, Naᵥ channels inactivate to prevent prolonged depolarization. Voltage-gated potassium channels (Kᵥ), such as those modeled in the squid axon, open with a delay during depolarization and contribute to repolarization by permitting K⁺ efflux, restoring the resting potential. The voltage-sensing domains of these channels, particularly the S4 segments rich in positively charged residues, detect voltage changes and couple them to pore opening, as quantitatively described in foundational electrophysiological studies.[43][44] The gating of ion channels involves intricate conformational rearrangements within the protein structure, often mediated by allosteric regulation where a stimulus at one site influences the pore domain remotely. In both ligand- and voltage-gated channels, agonist or voltage binding triggers tertiary and quaternary structural shifts, such as helix tilting or subunit rotation, that dilate the intracellular gate or selectivity filter to permit ion permeation. For instance, in pentameric ligand-gated channels like nAChR, ligand binding at the orthosteric site propagates through a transduction pathway involving the membrane-spanning domains, leading to an iris-like expansion of the pore. Allosteric modulators, including lipids or auxiliary subunits, can fine-tune these transitions by stabilizing specific conformations, enhancing or inhibiting channel activity without directly occluding the pore.[45][41] Ion selectivity in gated channels is maintained by narrow selectivity filters composed of amino acid motifs that coordinate permeant ions while excluding others, ensuring fidelity in potential modulation. In voltage-gated sodium channels, the DEKA motif—formed by aspartate (D) from domain I, glutamate (E) from domain II, lysine (K) from domain III, and alanine (A) from domain IV—creates an asymmetric ring of charges in the pore. The negative charges from D and E attract Na⁺, while the positive K repels K⁺ and other larger cations, achieving high Na⁺/K⁺ selectivity ratios (up to 10:1). Structural studies reveal that this motif dehydrates Na⁺ partially, stabilizing it via carbonyl oxygen interactions, a mechanism conserved across eukaryotic Naᵥ channels but distinct from the symmetric EEEE filter in calcium channels.[46][47]Equilibrium and Potential Calculations

Reversal potential

The reversal potential for an ion, denoted as , is the specific membrane voltage at which the net flow of that ion through an open, selective channel is zero, as the chemical driving force from the concentration gradient is exactly balanced by the opposing electrical driving force across the membrane.[22] This equilibrium point arises because the electrochemical gradient for the ion vanishes, preventing any net movement despite the channel being permeable to it.[22] For instance, in neurons, the reversal potential reflects the voltage needed to counteract the typical intracellular-extracellular concentration differences maintained by ion pumps and transporters.[22] The reversal potential is ion-specific and determines the direction and magnitude of current flow through channels permeable to that ion. When the membrane potential is more negative than for a cation like Na or Ca, the net current is inward, depolarizing the cell; conversely, if exceeds , the current reverses to outward flow, contributing to hyperpolarization.[22] This property is fundamental to how ion channels shape electrical signaling in excitable cells, such as neurons and muscle fibers, by dictating whether channel activation drives the membrane toward excitation or inhibition. Experimentally, reversal potentials are identified from current-voltage (I-V) relationships, where the voltage at which the measured ionic current changes sign—reversing from inward to outward or vice versa—is the . In pioneering voltage-clamp studies on squid giant axons, Hodgkin and Huxley varied the membrane potential and observed this reversal point for sodium and potassium currents, establishing it as a key parameter for understanding action potential dynamics. Modern patch-clamp techniques extend this approach to single channels, generating precise I-V curves by stepping voltages in isolated membrane patches to directly measure the reversal for specific ion-selective conductances.[48]Nernst equation