Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Extreme value theory

View on Wikipedia

Extreme value theory or extreme value analysis (EVA) is the study of extremes in statistical distributions.

It is widely used in many disciplines, such as structural engineering, finance, economics, earth sciences, traffic prediction, and geological engineering. For example, EVA might be used in the field of hydrology to estimate the probability of an unusually large flooding event, such as the 100-year flood. Similarly, for the design of a breakwater, a coastal engineer would seek to estimate the 50 year wave and design the structure accordingly.

Data analysis

[edit]Two main approaches exist for practical extreme value analysis.

The first method relies on deriving block maxima (minima) series as a preliminary step. In many situations it is customary and convenient to extract the annual maxima (minima), generating an annual maxima series (AMS).

The second method relies on extracting, from a continuous record, the peak values reached for any period during which values exceed a certain threshold (falls below a certain threshold). This method is generally referred to as the peak over threshold method (POT).[1]

For AMS data, the analysis may partly rely on the results of the Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem, leading to the generalized extreme value distribution being selected for fitting.[2][3] However, in practice, various procedures are applied to select between a wider range of distributions. The theorem here relates to the limiting distributions for the minimum or the maximum of a very large collection of independent random variables from the same distribution. Given that the number of relevant random events within a year may be rather limited, it is unsurprising that analyses of observed AMS data often lead to distributions other than the generalized extreme value distribution (GEVD) being selected.[4]

For POT data, the analysis may involve fitting two distributions: One for the number of events in a time period considered and a second for the size of the exceedances.

A common assumption for the first is the Poisson distribution, with the generalized Pareto distribution being used for the exceedances. A tail-fitting can be based on the Pickands–Balkema–de Haan theorem.[5][6]

Novak (2011) reserves the term "POT method" to the case where the threshold is non-random, and distinguishes it from the case where one deals with exceedances of a random threshold.[7]

Applications

[edit]Applications of extreme value theory include predicting the probability distribution of:

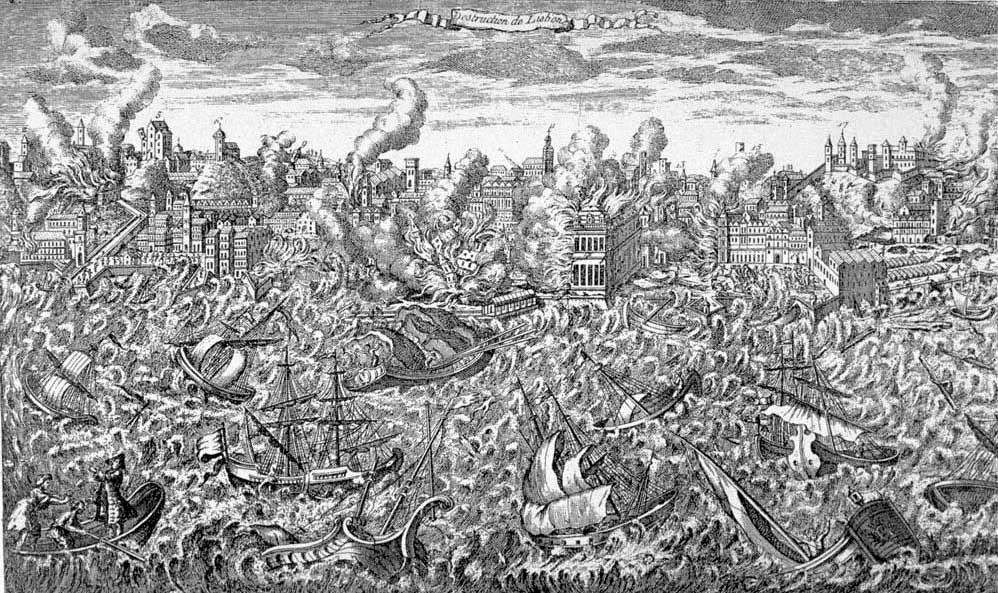

- Extreme floods; the size of freak waves

- Tornado outbreaks[8]

- Maximum sizes of ecological populations[9]

- Side effects of drugs (e.g., ximelagatran)

- The magnitudes of large insurance losses

- Equity risks; day-to-day market risk

- Mutation events during evolution

- Large wildfires[10]

- Environmental loads on structures[11]

- Time the fastest humans could ever run the 100 metres sprint[12] and performances in other athletic disciplines[13][14][15]

- Pipeline failures due to pitting corrosion

- Anomalous IT network traffic, prevent attackers from reaching important data

- Road safety analysis[16][17]

- Wireless communications[18]

- Epidemics[19]

- Neurobiology[20]

- Solar energy[21]

- Extreme Space weather[22][23][24][25]

- Weather,[26] extreme temperature/climate change[27]

History

[edit]The field of extreme value theory was pioneered by L. Tippett (1902–1985). Tippett was employed by the British Cotton Industry Research Association, where he worked to make cotton thread stronger. In his studies, he realized that the strength of a thread was controlled by the strength of its weakest fibres. With the help of R.A. Fisher, Tippet obtained three asymptotic limits describing the distributions of extremes assuming independent variables. E.J. Gumbel (1958)[28] codified this theory. These results can be extended to allow for slight correlations between variables, but the classical theory does not extend to strong correlations of the order of the variance. One universality class of particular interest is that of log-correlated fields, where the correlations decay logarithmically with the distance.

Univariate theory

[edit]The theory for extreme values of a single variable is governed by the extreme value theorem, also called the Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem, which describes which of the three possible distributions for extreme values applies for a particular statistical variable .

Multivariate theory

[edit]Extreme value theory in more than one variable introduces additional issues that have to be addressed. One problem that arises is that one must specify what constitutes an extreme event.[29] Although this is straightforward in the univariate case, there is no unambiguous way to do this in the multivariate case. The fundamental problem is that although it is possible to order a set of real-valued numbers, there is no natural way to order a set of vectors.

As an example, in the univariate case, given a set of observations it is straightforward to find the most extreme event simply by taking the maximum (or minimum) of the observations. However, in the bivariate case, given a set of observations , it is not immediately clear how to find the most extreme event. Suppose that one has measured the values at a specific time and the values at a later time. Which of these events would be considered more extreme? There is no universal answer to this question.

Another issue in the multivariate case is that the limiting model is not as fully prescribed as in the univariate case. In the univariate case, the model (GEV distribution) contains three parameters whose values are not predicted by the theory and must be obtained by fitting the distribution to the data. In the multivariate case, the model not only contains unknown parameters, but also a function whose exact form is not prescribed by the theory. However, this function must obey certain constraints.[30][31] It is not straightforward to devise estimators that obey such constraints though some have been recently constructed.[32][33][34]

As an example of an application, bivariate extreme value theory has been applied to ocean research.[29][35]

Non-stationary extremes

[edit]Statistical modeling for nonstationary time series was developed in the 1990s.[36] Methods for nonstationary multivariate extremes have been introduced more recently.[37] The latter can be used for tracking how the dependence between extreme values changes over time, or over another covariate.[38][39][40]

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ Leadbetter, M.R. (1991). "On a basis for 'peaks over threshold' modeling". Statistics and Probability Letters. 12 (4): 357–362. doi:10.1016/0167-7152(91)90107-3.

- ^ Fisher & Tippett (1928)

- ^ Gnedenko (1943)

- ^ Embrechts, Klüppelberg & Mikosch (1997)

- ^ Pickands (1975)

- ^ Balkema & de Haan (1974)

- ^ Novak (2011)

- ^ Tippett, Lepore & Cohen (2016)

- ^ Batt, Ryan D.; Carpenter, Stephen R.; Ives, Anthony R. (March 2017). "Extreme events in lake ecosystem time series". Limnology and Oceanography Letters. 2 (3): 63. Bibcode:2017LimOL...2...63B. doi:10.1002/lol2.10037.

- ^ Alvarado, Sandberg & Pickford (1998), p. 68

- ^ Makkonen (2008)

- ^ Einmahl, J.H.J.; Smeets, S.G.W.R. (2009). Ultimate 100m world records through extreme-value theory (PDF) (Report). CentER Discussion Paper. Vol. 57. Tilburg University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ^ Gembris, D.; Taylor, J.; Suter, D. (2002). "Trends and random fluctuations in athletics". Nature. 417 (6888): 506. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..506G. doi:10.1038/417506a. hdl:2003/25362. PMID 12037557. S2CID 13469470.

- ^ Gembris, D.; Taylor, J.; Suter, D. (2007). "Evolution of athletic records: Statistical effects versus real improvements". Journal of Applied Statistics. 34 (5): 529–545. Bibcode:2007JApSt..34..529G. doi:10.1080/02664760701234850. hdl:2003/25404. PMC 11134017. PMID 38817921. S2CID 55378036.

- ^ Spearing, H.; Tawn, J.; Irons, D.; Paulden, T.; Bennett, G. (2021). "Ranking, and other properties, of elite swimmers using extreme value theory". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society). 184 (1): 368–395. arXiv:1910.10070. doi:10.1111/rssa.12628. S2CID 204823947.

- ^ Songchitruksa, P.; Tarko, A.P. (2006). "The extreme value theory approach to safety estimation". Accident Analysis and Prevention. 38 (4): 811–822. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2006.02.003. PMID 16546103.

- ^ Orsini, F.; Gecchele, G.; Gastaldi, M.; Rossi, R. (2019). "Collision prediction in roundabouts: A comparative study of extreme value theory approaches". Transportmetrica. Series A: Transport Science. 15 (2): 556–572. doi:10.1080/23249935.2018.1515271. S2CID 158343873.

- ^ Tsinos, C.G.; Foukalas, F.; Khattab, T.; Lai, L. (February 2018). "On channel selection for carrier aggregation systems". IEEE Transactions on Communications. 66 (2): 808–818. Bibcode:2018ITCom..66..808T. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2017.2757478. S2CID 3405114.

- ^ Wong, Felix; Collins, James J. (2 November 2020). "Evidence that coronavirus superspreading is fat-tailed". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 117 (47): 29416–29418. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11729416W. doi:10.1073/pnas.2018490117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7703634. PMID 33139561.

- ^ Basnayake, Kanishka; Mazaud, David; Bemelmans, Alexis; Rouach, Nathalie; Korkotian, Eduard; Holcman, David (4 June 2019). "Fast calcium transients in dendritic spines driven by extreme statistics". PLOS Biology. 17 (6) e2006202. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2006202. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 6548358. PMID 31163024.

- ^ Younis, Abubaker; Abdeljalil, Anwar; Omer, Ali (1 January 2023). "Determination of panel generation factor using peaks over threshold method and short-term data for an off-grid photovoltaic system in Sudan: A case of Khartoum city". Solar Energy. 249: 242–249. Bibcode:2023SoEn..249..242Y. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.11.039. ISSN 0038-092X. S2CID 254207549.

- ^ Fogg, Alexandra Ruth (2023). "Extreme Value Analysis of Ground Magnetometer Observations at Valentia Observatory, Ireland". Space Weather. 21 (e2023SW003565) e2023SW003565. Bibcode:2023SpWea..2103565F. doi:10.1029/2023SW003565.

- ^ Elvidge, Sean (2020). "Estimating the occurrence of geomagnetic activity using the Hilbert-Huang transform and extreme value theory". Space Weather. 17 (e2020SW002513) e2020SW002513. Bibcode:2020SpWea..1802513E. doi:10.1029/2020SW002513.

- ^ Bergin, Aisling (2023). "Extreme event statistics in Dst, SYM-H, and SMR geomagnetic indices". Space Weather. 21 (e2022SW003304) e2022SW003304. Bibcode:2023SpWea..2103304B. doi:10.1029/2022SW003304. hdl:10037/30641.

- ^ Fogg, Alexandra Ruth; Healy, D.; Jackman, C. M.; Parnell, A. C.; Rutala, M. J.; McEntee, S. C.; Walker, S. J.; Gallagher, P. T.; Bowers, C. F. (May 2025). "Bivariate Extreme Value Analysis for Space Weather Risk Assessment: Solar Wind—Magnetosphere Driving in the Terrestrial System". Space Weather. 23 (5) e2024SW004176. Bibcode:2025SpWea..2304176F. doi:10.1029/2024SW004176.

- ^ Finkel, Justin; Gerber, Edwin P.; Abbot, Dorian S.; Weare, Jonathan (April 2023). "Revealing the Statistics of Extreme Events Hidden in Short Weather Forecast Data". AGU Advances. 4 (2) e2023AV000881. arXiv:2206.05363. Bibcode:2023AGUA....400881F. doi:10.1029/2023AV000881.

- ^ Healy, Dáire; Tawn, Jonathan; Thorne, Peter; Parnell, Andrew (13 March 2025). "Inference for extreme spatial temperature events in a changing climate with application to Ireland". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C: Applied Statistics. 74 (2): 275–299. doi:10.1093/jrsssc/qlae047.

- ^ Gumbel (2004)

- ^ a b Morton, I.D.; Bowers, J. (December 1996). "Extreme value analysis in a multivariate offshore environment". Applied Ocean Research. 18 (6): 303–317. Bibcode:1996AppOR..18..303M. doi:10.1016/s0141-1187(97)00007-2. ISSN 0141-1187.

- ^ Beirlant, Jan; Goegebeur, Yuri; Teugels, Jozef; Segers, Johan (27 August 2004). Statistics of Extremes: Theory and applications. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/0470012382. ISBN 978-0-470-01238-3.

- ^ Coles, Stuart (2001). An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values. Springer Series in Statistics. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-3675-0. ISBN 978-1-84996-874-4. ISSN 0172-7397.

- ^ de Carvalho, M.; Davison, A.C. (2014). "Spectral density ratio models for multivariate extremes" (PDF). Journal of the American Statistical Association. 109: 764‒776. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2017.03.030. hdl:20.500.11820/9e2f7cff-d052-452a-b6a2-dc8095c44e0c. S2CID 53338058.

- ^ Hanson, T.; de Carvalho, M.; Chen, Yuhui (2017). "Bernstein polynomial angular densities of multivariate extreme value distributions" (PDF). Statistics and Probability Letters. 128: 60–66. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2017.03.030. hdl:20.500.11820/9e2f7cff-d052-452a-b6a2-dc8095c44e0c. S2CID 53338058.

- ^ de Carvalho, M. (2013). "A Euclidean likelihood estimator for bivariate tail dependence" (PDF). Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods. 42 (7): 1176–1192. arXiv:1204.3524. doi:10.1080/03610926.2012.709905. S2CID 42652601.

- ^ Zachary, S.; Feld, G.; Ward, G.; Wolfram, J. (October 1998). "Multivariate extrapolation in the offshore environment". Applied Ocean Research. 20 (5): 273–295. Bibcode:1998AppOR..20..273Z. doi:10.1016/s0141-1187(98)00027-3. ISSN 0141-1187.

- ^ Davison, A.C.; Smith, Richard (1990). "Models for exceedances over high thresholds". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological). 52 (3): 393–425. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1990.tb01796.x.

- ^ de Carvalho, M. (2016). "Statistics of extremes: Challenges and opportunities". Handbook of EVT and its Applications to Finance and Insurance (PDF). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley's Sons. pp. 195–214. ISBN 978-1-118-65019-6.

- ^ Castro, D.; de Carvalho, M.; Wadsworth, J. (2018). "Time-Varying Extreme Value Dependence with Application to Leading European Stock Markets" (PDF). Annals of Applied Statistics. 12: 283–309. doi:10.1214/17-AOAS1089. S2CID 33350408.

- ^ Mhalla, L.; de Carvalho, M.; Chavez-Demoulin, V. (2019). "Regression type models for extremal dependence" (PDF). Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 46 (4): 1141–1167. arXiv:1704.08447. doi:10.1111/sjos.12388. S2CID 53570822.

- ^ Mhalla, L.; de Carvalho, M.; Chavez-Demoulin, V. (2018). "Local robust estimation of the Pickands dependence function". Annals of Statistics. 46 (6A): 2806–2843. doi:10.1214/17-AOS1640. S2CID 59467614.

Sources

[edit]- Abarbanel, H.; Koonin, S.; Levine, H.; MacDonald, G.; Rothaus, O. (January 1992). "Statistics of extreme events with application to climate" (PDF). JASON. JSR-90-30S. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Alvarado, Ernesto; Sandberg, David V.; Pickford, Stewart G. (1998). "Modeling Large Forest Fires as Extreme Events" (PDF). Northwest Science. 72: 66–75. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Balkema, A.; de Haan, Laurens (1974). "Residual life time at great age". Annals of Probability. 2 (5): 792–804. doi:10.1214/aop/1176996548. JSTOR 2959306.

- Burry, K.V. (1975). Statistical Methods in Applied Science. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Castillo, E. (1988). Extreme Value Theory in Engineering. New York, NY: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-163475-2.

- Castillo, E.; Hadi, A.S.; Balakrishnan, N.; Sarabia, J.M. (2005). Extreme Value and Related Models with Applications in Engineering and Science. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley's Sons. ISBN 0-471-67172-X.

- Coles, S. (2001). An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values. London, UK: Springer.

- Embrechts, P.; Klüppelberg, C.; Mikosch, T. (1997). Modelling extremal events for insurance and finance. Berlin, DE: Springer Verlag.

- Fisher, R.A.; Tippett, L.H.C. (1928). "Limiting forms of the frequency distribution of the largest and smallest member of a sample". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 24 (2): 180–190. Bibcode:1928PCPS...24..180F. doi:10.1017/s0305004100015681. S2CID 123125823.

- Gnedenko, B.V. (1943). "Sur la distribution limite du terme maximum d'une serie aleatoire" [On the limiting distribution(s) of the maximum value of a series ...]. Annals of Mathematics (in French). 44 (3): 423–453. doi:10.2307/1968974. JSTOR 1968974.

- Gumbel, E.J., ed. (1935) [1933–1934]. "Les valeurs extrêmes des distributions statistiques" [The statistical distributions of extreme values] (pdf). Annales de l'Institut Henri Poincaré (conference papers) (in French). 5 (2). France: 115–158. Retrieved 2009-04-01 – via numdam.org.

- Gumbel, E.J. (2004) [1958]. Statistics of Extremes (reprint ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-43604-3.

- Makkonen, L. (2008). "Problems in the extreme value analysis". Structural Safety. 30 (5): 405–419. doi:10.1016/j.strusafe.2006.12.001.

- Leadbetter, M.R. (1991). "On a basis for 'peaks over threshold' modeling". Statistics & Probability Letters. 12 (4): 357–362. doi:10.1016/0167-7152(91)90107-3.

- Leadbetter, M.R.; Lindgren, G.; Rootzen, H. (1982). Extremes and Related Properties of Random Sequences and Processes. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Lindgren, G.; Rootzen, H. (1987). "Extreme values: Theory and technical applications". Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, Theory and Applications. 14: 241–279.

- Novak, S.Y. (2011). Extreme Value Methods with Applications to Finance. London, UK / Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall / CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-3574-6.

- Pickands, J. (1975). "Statistical inference using extreme order statistics". Annals of Statistics. 3: 119–131. doi:10.1214/aos/1176343003.

- Tippett, Michael K.; Lepore, Chiara; Cohen, Joel E. (16 December 2016). "More tornadoes in the most extreme U.S. tornado outbreaks". Science. 354 (6318): 1419–1423. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1419T. doi:10.1126/science.aah7393. PMID 27934705.

Software

[edit]- Belzile, L.R.; Dutang, C.; Northrop, P.J.; Opitz, T. (2023). "A modeler's guide to extreme value software". Extremes. 26 (4): 595–638. arXiv:2205.07714. doi:10.1007/s10687-023-00475-9.

- "Extreme Value Statistics in R". cran.r-project.org (software). 4 November 2023. — Package for extreme value statistics in R.

- "Extremes.jl". github.com (software). — Package for extreme value statistics in Julia.

- "Source code for stationary and non-stationary extreme value analysis". amir.eng.uci.edu (software). Irvine, CA: University of California, Irvine.

External links

[edit]- Chavez-Demoulin, Valérie; Roehrl, Armin (8 January 2004). Extreme value theory can save your neck (PDF). risknet.de (Report). Germany. — Easy non-mathematical introduction.

- Steps in applying extreme value theory to finance: A review (PDF). bankofcanada.ca (Report). Bank of Canada (published January 2010). c. 2010.

- Gumbel, E.J., ed. (1935) [1933–1934]. "Les valeurs extrêmes des distributions statistiques" [The statistical distributions of extreme values] (pdf). Annales de l'Institut Henri Poincaré (conference papers) (in French). 5 (2). France: 115–158. Retrieved 2009-04-01 – via numdam.org. — Full-text access to conferences held by E.J. Gumbel in 1933–1934.

Extreme value theory

View on GrokipediaFoundations and Principles

Core Concepts and Motivations

Extreme value theory (EVT) examines the statistical behavior of rare, outlier events that deviate substantially from the central tendency of a distribution, such as maxima or minima in sequences of random variables. Unlike the bulk of data, where phenomena like the central limit theorem lead to Gaussian approximations, extremes often exhibit tail behaviors that require distinct modeling due to their potential for disproportionate impacts. This separation arises because the tails of many empirical distributions display heavier or lighter dependence than predicted by normal distributions, reflecting the inadequacy of standard parametric assumptions for high-quantile predictions.[1][8] The primary motivation for EVT stems from the need to quantify risks associated with infrequent but severe occurrences, where underestimation can lead to catastrophic failures in fields like hydrology, finance, and engineering. For instance, floods in Taiwan or market crashes like the 2008 financial crisis demonstrate how extremes, driven by amplifying mechanisms in underlying generative processes—such as hydrological thresholds or economic contagions—generate losses far exceeding median expectations. Empirical studies reveal that conventional models fail here, as Gaussian tails decay too rapidly, prompting EVT to classify distributions into domains of attraction where normalized extremes converge to non-degenerate limits.[3][1][9] These domains correspond to three archetypal tail structures: the Fréchet domain for heavy-tailed distributions with power-law decay (e.g., certain stock returns), the Weibull domain for finite upper endpoints (e.g., material strengths), and the Gumbel domain for exponentially decaying tails (e.g., earthquake magnitudes). This classification, grounded in observations from datasets like rainfall extremes in Florida or wind speeds in New Zealand, underscores EVT's utility in identifying whether a process generates unbounded or bounded extremes, informing probabilistic forecasts beyond historical data.[8][1]Asymptotic Limit Theorems

The asymptotic limit theorems form the foundational mathematical results of extreme value theory, characterizing the possible non-degenerate limiting distributions for the normalized maxima of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables. For i.i.d. random variables drawn from a cumulative distribution function (cdf) with finite right endpoint or unbounded support, let . The theorems assert that if there exist normalizing sequences and such that the cdf of the normalized maximum converges pointwise to a non-degenerate limiting cdf , i.e., as for all continuity points of , then belongs to a specific family of distributions.[1][10] The Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem specifies that the only possible forms for are the Gumbel distribution for , the Fréchet distribution for and , or the reversed Weibull distribution for and . Fisher and Tippett derived these forms in 1928 by examining the stability of limiting distributions under repeated maxima operations, identifying them through asymptotic analysis of sample extremes from various parent distributions.[1] Gnedenko provided the first complete rigorous proof in 1943, establishing that no other non-degenerate limits exist and extending the result to minima via symmetry.[10] Central to these theorems is the concept of max-stability, which imposes an invariance principle on : for i.i.d. copies from , there must exist sequences and such that for all , ensuring the limit is unchanged under further maximization after renormalization. This functional equation uniquely determines the three parametric families, as solutions to it yield precisely the Gumbel, Fréchet, and reversed Weibull forms up to location-scale transformations.[1][11] Gnedenko further characterized the maximum domains of attraction (MDA), which are the classes of parent cdfs converging to each . For the Fréchet MDA, must exhibit regularly varying tails with index , satisfying for . The Gumbel MDA requires exponential-type tail decay, formalized by the von Mises condition that is in the MDA of Gumbel if for some auxiliary function , where . The reversed Weibull MDA applies to distributions with finite upper endpoint , where near , for constants , . These conditions ensure convergence and distinguish the attraction basins based on tail heaviness.[10][1]Historical Development

Early Foundations (Pre-1950)

The study of extreme values, particularly the distribution of maxima or minima in samples of independent identically distributed random variables, traces back to at least 1709, when Nicholas Bernoulli posed the problem of determining the probability that all values in a sample of fixed size lie within a specified interval, highlighting early interest in bounding extremes.[12] A precursor to formal extreme value considerations emerged in 1906 with Vilfredo Pareto's analysis of income distributions, where he identified power-law heavy tails—manifesting as the 80/20 rule, with approximately 20% of the population controlling 80% of the wealth—providing an empirical basis for modeling unbounded large deviations in socioeconomic data that foreshadowed later heavy-tailed limit forms.[13] Significant progress occurred in the 1920s, beginning with Maurice Fréchet's 1927 derivation of a stable limiting distribution for sample maxima under assumptions of regularly varying tails, applicable to phenomena with no finite upper bound.[14] In 1928, Ronald A. Fisher and Leonard H. C. Tippett conducted numerical simulations on maxima from diverse parent distributions—such as normal, exponential, gamma, and beta—revealing three asymptotic forms: Type I for distributions with exponentially decaying tails (resembling a double exponential), Type II for heavy-tailed cases like Pareto (power-law decay), and Type III for bounded upper endpoints (reverse Weibull-like). Their classification, drawn from computational approximations rather than proofs, was motivated by practical needs in assessing material strength extremes, including yarn breakage frequencies in the British cotton industry, where Tippett worked.[15][14] These early efforts found initial applications in hydrology for estimating rare flood levels from limited river gauge data and in insurance for quantifying tail risks in claim sizes, yet were constrained by dependence on simulations for specific distributions, absence of general convergence theorems, and challenges in verifying asymptotic behavior from finite samples.[16][17]Post-War Formalization and Expansion (1950-1990)

The post-war era marked a phase of rigorous mathematical maturation for extreme value theory, building on pre-1950 foundations to establish precise asymptotic results for maxima and minima. Boris Gnedenko's 1943 theorem, which characterized the limiting distributions of normalized maxima as belonging to one of three types (Fréchet, Weibull, or Gumbel), gained wider formal dissemination and application in statistical literature during this period, providing the canonical framework for univariate extremes.[18] Emil J. Gumbel's 1958 monograph Statistics of Extremes synthesized these results, deriving exact distributions for extremes, analyzing first- and higher-order asymptotes, and demonstrating applications to flood frequencies and material strengths with empirical data from over 40 datasets, thereby popularizing the theory among engineers and hydrologists.[19] Laurens de Haan's contributions in the late 1960s and 1970s introduced regular variation as a cornerstone for tail analysis, with his 1970 work proving weak convergence of sample maxima under regularly varying conditions on the underlying distribution, enabling precise domain-of-attraction criteria beyond mere existence of limits.[8] This facilitated expansions to records—successive new maxima—and spacings between order statistics, where asymptotic independence or dependence structures were quantified for non-i.i.d. settings. A landmark theorem by A. A. Balkema and de Haan in 1974, complemented by J. Pickands III in 1975, established that for distributions in the generalized extreme value domain of attraction, the conditional excess over a high threshold converges in distribution to a generalized Pareto law, provided the threshold recedes appropriately to infinity.[20] This result underpinned the peaks-over-threshold approach, shifting focus from block maxima to threshold exceedances for more efficient use of data in the tails. By 1983, M. R. Leadbetter, G. Lindgren, and H. Rootzén's treatise Extremes and Related Properties of Random Sequences and Processes generalized these to stationary sequences, deriving conditions for extremal index to measure clustering in dependent data and extending limit theorems to processes with mixing properties, thus broadening applicability to time series like wind speeds and stock returns.[21]Contemporary Refinements (1990-Present)

Since the 1990s, extreme value theory (EVT) has advanced through rigorous treatments of heavy-tailed phenomena, with Sidney Resnick's 2007 monograph Heavy-Tail Phenomena: Probabilistic and Statistical Modeling synthesizing probabilistic foundations, regular variation, and point process techniques to model distributions prone to extreme outliers, extending earlier work on regular variation for tail behavior.[22] This framework emphasized empirical tail estimation via Hill's estimator and Pareto approximations, addressing limitations in lighter-tailed assumptions prevalent in pre-1990 models.[23] Parallel developments addressed multivariate dependence beyond asymptotic independence, as Ledford and Tawn introduced conditional extreme value models in 1996 to quantify near-independence via tail dependence coefficients (η ∈ (0,1]), allowing flexible specification of joint tail decay rates without restricting to max-stable processes.[24] Heffernan and Tawn's 2004 extension formalized a conditional approach, approximating the distribution of one variable exceeding a high threshold given another's extremeness, using linear-normal approximations for sub-asymptotic regions; applied to air pollution data, it revealed site-specific dependence asymmetries consistent with physical dispersion mechanisms.[25] These models improved inference for datasets with 10^3–10^5 observations, outperforming logistic alternatives in likelihood-based diagnostics.[26] In the 2020s, theoretical refinements incorporated non-stationarity driven by climate covariates, with non-stationary generalized extreme value (GEV) distributions parameterizing location/scale/shape via linear trends or predictors like sea surface temperatures; a 2022 study constrained projections of 100-year return levels for temperature/precipitation extremes using joint historical-future fitting, reducing biases from stationary assumptions by up to 20% in ensemble means.[27] Empirical validations from global datasets (e.g., ERA5 reanalysis spanning 1950–2020) demonstrated parameter trends—such as increasing GEV scale for heatwaves—aligning with thermodynamic scaling under warming, challenging stationarity in risk assessment for events exceeding historical precedents.[28] Bayesian implementations like non-stationary EVT analysis (NEVA) further enabled probabilistic quantification of return level uncertainties, incorporating prior elicitations from physics-based simulations.[28] Geometric extremes frameworks have emerged as a recent push for spatial/multivariate settings, reformulating tail dependence via directional measures on manifolds to handle anisotropy in high dimensions; sessions at the EVA 2025 conference introduced statistical inference for these, extending to non-stationary processes via covariate-modulated geometries.[29] Such approaches, grounded in limit theorems for angular measures, facilitate scalable computation for gridded climate data, with preliminary simulations showing improved fit over Gaussian copulas for storm tracks.[30]Univariate Extreme Value Theory

Generalized Extreme Value Distribution

The generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution serves as the asymptotic limiting form for the distribution of normalized block maxima from a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables, unifying the three classical extreme value types under a single parametric family.[31][32] Its cumulative distribution function is defined aswhere is the location parameter, is the scale parameter, is the shape parameter, and denotes the positive part (i.e., ), with the support restricted to such that .[31][8] For , the distribution is obtained as the limiting case

corresponding to the Gumbel distribution.[32][31] The shape parameter governs the tail characteristics and domain of attraction: yields the Fréchet class, featuring heavy right tails and an unbounded upper support suitable for distributions with power-law decay; produces the Gumbel class with exponentially decaying tails and unbounded support; results in the reversed Weibull class, with a finite upper endpoint at and lighter tails bounded above.[33][34] These cases align with the extremal types theorem, where the GEV captures the possible limiting behaviors for maxima from parent distributions in the respective domains of attraction.[35] In application to block maxima—obtained by partitioning time series into non-overlapping blocks (e.g., annual periods) and selecting the maximum value per block—the GEV provides a model for extrapolating beyond observed extremes under stationarity assumptions.[32][36] Fit adequacy to empirical block maxima can be assessed through quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots, which graphically compare sample quantiles against GEV theoretical quantiles to detect deviations in tail behavior or overall alignment.[37]