Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poisson distribution

View on Wikipedia

| Poisson distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Probability mass function  The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. λ is the expected rate of occurrences. The vertical axis is the probability of k occurrences given λ. The function is defined only at integer values of k; the connecting lines are only guides for the eye. | |||

|

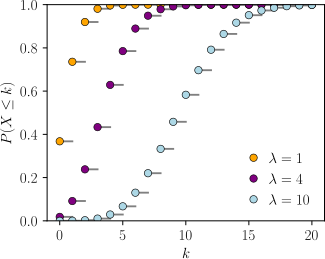

Cumulative distribution function  The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. The CDF is discontinuous at the integers of k and flat everywhere else because a variable that is Poisson distributed takes on only integer values. | |||

| Notation | |||

| Parameters | (rate) | ||

| Support | (Natural numbers starting from 0) | ||

| PMF | |||

| CDF |

or or (for where is the upper incomplete gamma function, is the floor function, and is the regularized gamma function) | ||

| Mean | |||

| Median | |||

| Mode | |||

| Variance | |||

| Skewness | |||

| Excess kurtosis | |||

| Entropy |

or for large | ||

| MGF | |||

| CF | |||

| PGF | |||

| Fisher information | |||

In probability theory and statistics, the Poisson distribution (/ˈpwɑːsɒn/) is a discrete probability distribution that expresses the probability of a given number of events occurring in a fixed interval of time if these events occur with a known constant mean rate and independently of the time since the last event.[1] It can also be used for the number of events in other types of intervals than time, and in dimension greater than 1 (e.g., number of events in a given area or volume). The Poisson distribution is named after French mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson. It plays an important role for discrete-stable distributions.

Under a Poisson distribution with the expectation of λ events in a given interval, the probability of k events in the same interval is:[2]: 60 For instance, consider a call center which receives an average of λ = 3 calls per minute at all times of day. If the number of calls received in any two given disjoint time intervals is independent, then the number k of calls received during any minute has a Poisson probability distribution. Receiving k = 1 to 4 calls then has a probability of about 0.77, while receiving 0 or at least 5 calls has a probability of about 0.23.

A classic example used to motivate the Poisson distribution is the number of radioactive decay events during a fixed observation period.[3]

History

[edit]The distribution was first introduced by Siméon Denis Poisson (1781–1840) and published together with his probability theory in his work Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile (1837).[4]: 205-207 The work theorized about the number of wrongful convictions in a given country by focusing on certain random variables N that count, among other things, the number of discrete occurrences (sometimes called "events" or "arrivals") that take place during a time-interval of given length. The result had already been given in 1711 by Abraham de Moivre in De Mensura Sortis seu; de Probabilitate Eventuum in Ludis a Casu Fortuito Pendentibus .[5]: 219 [6]: 14-15 [7]: 193 [8]: 157 This makes it an example of Stigler's law and it has prompted some authors to argue that the Poisson distribution should bear the name of de Moivre.[9][10]

In 1860, Simon Newcomb fitted the Poisson distribution to the number of stars found in a unit of space.[11] A further practical application was made by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz in 1898. Bortkiewicz showed that the frequency with which soldiers in the Prussian army were accidentally killed by horse kicks could be well modeled by a Poisson distribution.[12]: 23-25 .

Definitions

[edit]Probability mass function

[edit]A discrete random variable X is said to have a Poisson distribution with parameter if it has a probability mass function given by:[2]: 60 where

- k is the number of occurrences ()

- e is Euler's number ()

- k! = k(k–1) ··· (3)(2)(1) is the factorial.

The positive real number λ is equal to the expected value of X and also to its variance.[13]

The Poisson distribution can be applied to systems with a large number of possible events, each of which is rare. The number of such events that occur during a fixed time interval is, under the right circumstances, a random number with a Poisson distribution.

The equation can be adapted if, instead of the average number of events we are given the average rate at which events occur. Then and:[14]

Examples

[edit]

The Poisson distribution may be useful to model events such as:

- the number of meteorites greater than 1-meter diameter that strike Earth in a year;

- the number of laser photons hitting a detector in a particular time interval;

- the number of students achieving a low and high mark in an exam; and

- locations of defects and dislocations in materials.

Examples of the occurrence of random points in space are: the locations of asteroid impacts with earth (2-dimensional), the locations of imperfections in a material (3-dimensional), and the locations of trees in a forest (2-dimensional).[15]

Assumptions and validity

[edit]The Poisson distribution is an appropriate model if the following assumptions are true:

- k, a nonnegative integer, is the number of times an event occurs in an interval.

- The occurrence of one event does not affect the probability of a second event.

- The average rate at which events occur is independent of any occurrences.

- Two events cannot occur at exactly the same instant.

If these conditions are true, then k is a Poisson random variable; the distribution of k is a Poisson distribution.

The Poisson distribution is also the limit of a binomial distribution, for which the probability of success for each trial is , where is the expectation and is the number of trials, in the limit that with kept constant [16][17] (see Related distributions): The Poisson distribution may also be derived from the differential equations[18][19][20] with initial conditions and evaluated at

Examples of probability for Poisson distributions

[edit]|

On a particular river, overflow floods occur once every 100 years on average. Calculate the probability of k = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 overflow floods in a 100-year interval, assuming the Poisson model is appropriate. Because the average event rate is one overflow flood per 100 years, λ = 1

|

The probability for 0 to 6 overflow floods in a 100-year period. |

|

In this example, it is reported that the average number of goals in a World Cup soccer match is approximately 2.5 and the Poisson model is appropriate.[21] Because the average event rate is 2.5 goals per match, λ = 2.5.

|

The probability for 0 to 7 goals in a match. |

Examples that violate the Poisson assumptions

[edit]The number of students who arrive at the student union per minute will likely not follow a Poisson distribution, because the rate is not constant (low rate during class time, high rate between class times) and the arrivals of individual students are not independent (students tend to come in groups). The non-constant arrival rate may be modeled as a mixed Poisson distribution, and the arrival of groups rather than individual students as a compound Poisson process.

The number of magnitude 5 earthquakes per year in a country may not follow a Poisson distribution, if one large earthquake increases the probability of aftershocks of similar magnitude.

Examples in which at least one event is guaranteed are not Poisson distributed; but may be modeled using a zero-truncated Poisson distribution.

Count distributions in which the number of intervals with zero events is higher than predicted by a Poisson model may be modeled using a zero-inflated model.

Properties

[edit]Descriptive statistics

[edit]- The expected value of a Poisson random variable is λ.

- The variance of a Poisson random variable is also λ.

- The coefficient of variation is while the index of dispersion is 1.[8]: 163

- The mean absolute deviation about the mean is[8]: 163

- The mode of a Poisson-distributed random variable with non-integer λ is equal to which is the largest integer less than or equal to λ. This is also written as floor(λ). When λ is a positive integer, the modes are λ and λ − 1.

- All of the cumulants of the Poisson distribution are equal to the expected value λ. The n-th factorial moment of the Poisson distribution is λn.

- The expected value of a Poisson process is sometimes decomposed into the product of intensity and exposure (or more generally expressed as the integral of an "intensity function" over time or space, sometimes described as "exposure").[22]

Median

[edit]Bounds for the median () of the distribution are known and are sharp:[23]

Higher moments

[edit]The higher non-centered moments mk of the Poisson distribution are Touchard polynomials in λ: where the braces { } denote Stirling numbers of the second kind.[24][1]: 6 In other words, When the expected value is set to λ = 1, Dobinski's formula implies that the n‑th moment is equal to the number of partitions of a set of size n.

A simple upper bound is:[25]

Sums of Poisson-distributed random variables

[edit]If for are independent, then [26]: 65 A converse is Raikov's theorem, which says that if the sum of two independent random variables is Poisson-distributed, then so are each of those two independent random variables.[27][28]

Maximum entropy

[edit]It is a maximum-entropy distribution among the set of generalized binomial distributions with mean and ,[29] where a generalized binomial distribution is defined as a distribution of the sum of N independent but not identically distributed Bernoulli variables.

Other properties

[edit]- The Poisson distributions are infinitely divisible probability distributions.[30]: 233 [8]: 164

- The directed Kullback–Leibler divergence of from is given by

- If is an integer, then satisfies and [31][failed verification – see discussion]

- Bounds for the tail probabilities of a Poisson random variable can be derived using a Chernoff bound argument.[32]: 97-98

- The upper tail probability can be tightened (by a factor of at least two) as follows:[33] where is the Kullback–Leibler divergence of from .

- Inequalities that relate the distribution function of a Poisson random variable to the Standard normal distribution function are as follows:[34]

where is the Kullback–Leibler divergence of from and is the Kullback–Leibler divergence of from .

Poisson races

[edit]Let and be independent random variables, with then we have that

The upper bound is proved using a standard Chernoff bound.

The lower bound can be proved by noting that is the probability that where which is bounded below by where is relative entropy (See the entry on bounds on tails of binomial distributions for details). Further noting that and computing a lower bound on the unconditional probability gives the result. More details can be found in the appendix of Kamath et al.[35]

Related distributions

[edit]As a Binomial distribution with infinitesimal time-steps

[edit]The Poisson distribution can be derived as a limiting case to the binomial distribution as the number of trials goes to infinity and the expected number of successes remains fixed — see law of rare events below. Therefore, it can be used as an approximation of the binomial distribution if n is sufficiently large and p is sufficiently small. The Poisson distribution is a good approximation of the binomial distribution if n is at least 20 and p is smaller than or equal to 0.05, and an excellent approximation if n ≥ 100 and np ≤ 10.[36] Letting and be the respective cumulative density functions of the binomial and Poisson distributions, one has: One derivation of this uses probability-generating functions.[37] Consider a Bernoulli trial (coin-flip) whose probability of one success (or expected number of successes) is within a given interval. Split the interval into n parts, and perform a trial in each subinterval with probability . The probability of k successes out of n trials over the entire interval is then given by the binomial distribution whose generating function is: Taking the limit as n increases to infinity (with x fixed) and applying the product limit definition of the exponential function, this reduces to the generating function of the Poisson distribution:

General

[edit]- If and are independent, then the difference follows a Skellam distribution.

- If and are independent, then the distribution of conditional on is a binomial distribution. Specifically, if then More generally, if X1, X2, ..., Xn are independent Poisson random variables with parameters λ1, λ2, ..., λn then given it follows that In fact,

- If and the distribution of conditional on X = k is a binomial distribution, then the distribution of Y follows a Poisson distribution In fact, if, conditional on follows a multinomial distribution, then each follows an independent Poisson distribution

- The Poisson distribution is a special case of the discrete compound Poisson distribution (or stuttering Poisson distribution) with only a parameter.[38][39] The discrete compound Poisson distribution can be deduced from the limiting distribution of univariate multinomial distribution. It is also a special case of a compound Poisson distribution.

- For sufficiently large values of λ, (say λ > 1000), the normal distribution with mean λ and variance λ (standard deviation ) is an excellent approximation to the Poisson distribution. If λ is greater than about 10, then the normal distribution is a good approximation if an appropriate continuity correction is performed, i.e., if P(X ≤ x), where x is a non-negative integer, is replaced by P(X ≤ x + 0.5).

- Variance-stabilizing transformation: If then[8]: 168 and[40]: 196 Under this transformation, the convergence to normality (as increases) is far faster than the untransformed variable.[citation needed] Other, slightly more complicated, variance stabilizing transformations are available,[8]: 168 one of which is Anscombe transform.[41] See Data transformation (statistics) for more general uses of transformations.

- If for every t > 0 the number of arrivals in the time interval [0, t] follows the Poisson distribution with mean λt, then the sequence of inter-arrival times are independent and identically distributed exponential random variables having mean 1/λ.[42]: 317–319

- The cumulative distribution functions of the Poisson and chi-squared distributions are related in the following ways:[8]: 167 and[8]: 158

Poisson approximation

[edit]Assume where then[43] is multinomially distributed conditioned on

This means[32]: 101-102 , among other things, that for any nonnegative function if is multinomially distributed, then where

The factor of can be replaced by 2 if is further assumed to be monotonically increasing or decreasing.

Bivariate Poisson distribution

[edit]This distribution has been extended to the bivariate case.[44] The generating function for this distribution is with

The marginal distributions are Poisson(θ1) and Poisson(θ2) and the correlation coefficient is limited to the range

A simple way to generate a bivariate Poisson distribution is to take three independent Poisson distributions with means and then set The probability function of the bivariate Poisson distribution is

Free Poisson distribution

[edit]The free Poisson distribution[45] with jump size and rate arises in free probability theory as the limit of repeated free convolution as N → ∞.

In other words, let be random variables so that has value with probability and value 0 with the remaining probability. Assume also that the family are freely independent. Then the limit as of the law of is given by the Free Poisson law with parameters

This definition is analogous to one of the ways in which the classical Poisson distribution is obtained from a (classical) Poisson process.

The measure associated to the free Poisson law is given by[46] where and has support

This law also arises in random matrix theory as the Marchenko–Pastur law. Its free cumulants are equal to

Some transforms of this law

[edit]We give values of some important transforms of the free Poisson law; the computation can be found in e.g. in the book Lectures on the Combinatorics of Free Probability by A. Nica and R. Speicher[47]

The R-transform of the free Poisson law is given by

The Cauchy transform (which is the negative of the Stieltjes transformation) is given by

The S-transform is given by in the case that

Statistical inference

[edit]Parameter estimation

[edit]Given a sample of n measured values for i = 1, ..., n, we wish to estimate the value of the parameter λ of the Poisson population from which the sample was drawn. The maximum likelihood estimate is[48]

Since each observation has expectation λ, so does the sample mean. Therefore, the maximum likelihood estimate is an unbiased estimator of λ. It is also an efficient estimator since its variance achieves the Cramér–Rao lower bound (CRLB).[49] Hence it is minimum-variance unbiased. Also it can be proven that the sum (and hence the sample mean as it is a one-to-one function of the sum) is a complete and sufficient statistic for λ.

To prove sufficiency we may use the factorization theorem. Consider partitioning the probability mass function of the joint Poisson distribution for the sample into two parts: one that depends solely on the sample , called , and one that depends on the parameter and the sample only through the function Then is a sufficient statistic for

The first term depends only on . The second term depends on the sample only through Thus, is sufficient.

To find the parameter λ that maximizes the probability function for the Poisson population, we can use the logarithm of the likelihood function:

We take the derivative of with respect to λ and compare it to zero:

Solving for λ gives a stationary point.

So λ is the average of the ki values. Obtaining the sign of the second derivative of L at the stationary point will determine what kind of extreme value λ is.

Evaluating the second derivative at the stationary point gives:

which is the negative of n times the reciprocal of the average of the ki. This expression is negative when the average is positive. If this is satisfied, then the stationary point maximizes the probability function.

For completeness, a family of distributions is said to be complete if and only if implies that for all If the individual are iid then Knowing the distribution we want to investigate, it is easy to see that the statistic is complete.

For this equality to hold, must be 0. This follows from the fact that none of the other terms will be 0 for all in the sum and for all possible values of Hence, for all implies that and the statistic has been shown to be complete.

Confidence interval

[edit]The confidence interval for the mean of a Poisson distribution can be expressed using the relationship between the cumulative distribution functions of the Poisson and chi-squared distributions. The chi-squared distribution is itself closely related to the gamma distribution, and this leads to an alternative expression. Given an observation k from a Poisson distribution with mean μ, a confidence interval for μ with confidence level 1 – α is

or equivalently,

where is the quantile function (corresponding to a lower tail area p) of the chi-squared distribution with n degrees of freedom and is the quantile function of a gamma distribution with shape parameter n and scale parameter 1.[8]: 176-178 [50] This interval is 'exact' in the sense that its coverage probability is never less than the nominal 1 – α.

When quantiles of the gamma distribution are not available, an accurate approximation to this exact interval has been proposed (based on the Wilson–Hilferty transformation):[51] where denotes the standard normal deviate with upper tail area α / 2.

For application of these formulae in the same context as above (given a sample of n measured values ki each drawn from a Poisson distribution with mean λ), one would set

calculate an interval for μ = nλ, and then derive the interval for λ.

Bayesian inference

[edit]In Bayesian inference, the conjugate prior for the rate parameter λ of the Poisson distribution is the gamma distribution.[52] Let

denote that λ is distributed according to the gamma density g parameterized in terms of a shape parameter α and an inverse scale parameter β:

Then, given the same sample of n measured values ki as before, and a prior of Gamma(α, β), the posterior distribution is

Note that the posterior mean is linear and is given by It can be shown that gamma distribution is the only prior that induces linearity of the conditional mean. Moreover, a converse result exists which states that if the conditional mean is close to a linear function in the distance than the prior distribution of λ must be close to gamma distribution in Levy distance.[53]

The posterior mean E[λ] approaches the maximum likelihood estimate in the limit as which follows immediately from the general expression of the mean of the gamma distribution.

The posterior predictive distribution for a single additional observation is a negative binomial distribution,[54]: 53 sometimes called a gamma–Poisson distribution.

Simultaneous estimation of multiple Poisson means

[edit]Suppose is a set of independent random variables from a set of Poisson distributions, each with a parameter and we would like to estimate these parameters. Then, Clevenson and Zidek show that under the normalized squared error loss when then, similar as in Stein's example for the Normal means, the MLE estimator is inadmissible.[55]

In this case, a family of minimax estimators is given for any and as[56]

Occurrence and applications

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

Some applications of the Poisson distribution to count data (number of events):[57]

- telecommunication: telephone calls arriving in a system,

- astronomy: photons arriving at a telescope,

- chemistry: the molar mass distribution of a living polymerization,[58]

- biology: the number of mutations on a strand of DNA per unit length,

- management: customers arriving at a counter or call centre,[59]

- finance and insurance: number of losses or claims occurring in a given period of time,

- seismology: asymptotic Poisson model of risk for large earthquakes,[60]

- radioactivity: decays in a given time interval in a radioactive sample,[61]

- optics: number of photons emitted in a single laser pulse (a major vulnerability of quantum key distribution protocols, known as photon number splitting).

More examples of counting events that may be modelled as Poisson processes include:

- soldiers killed by horse-kicks each year in each corps in the Prussian cavalry. This example was used in a book by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz (1868–1931),[12]: 23-25

- yeast cells used when brewing Guinness beer. This example was used by William Sealy Gosset (1876–1937),[62][63]

- phone calls arriving at a call centre within a minute. This example was described by A.K. Erlang (1878–1929),[64]

- goals in sports involving two competing teams,[65]

- deaths per year in a given age group,[66]

- jumps in a stock price in a given time interval,

- times a web server is accessed per minute (under an assumption of homogeneity),

- mutations in a given stretch of DNA after a certain amount of radiation,

- cells infected at a given multiplicity of infection,

- bacteria in a certain amount of liquid,[67]

- photons arriving on a pixel circuit at a given illumination over a given time period,[68]

- landing of V-1 flying bombs on London during World War II, investigated by R. D. Clarke in 1946.[69]

In probabilistic number theory, Gallagher showed in 1976 that, if a certain version of the unproved prime r-tuple conjecture holds,[70] then the counts of prime numbers in short intervals would obey a Poisson distribution.[71]

Law of rare events

[edit]

The rate of an event is related to the probability of an event occurring in some small subinterval (of time, space or otherwise). In the case of the Poisson distribution, one assumes that there exists a small enough subinterval for which the probability of an event occurring twice is "negligible". With this assumption one can derive the Poisson distribution from the binomial one, given only the information of expected number of total events in the whole interval.

Let the total number of events in the whole interval be denoted by Divide the whole interval into subintervals of equal size, such that (since we are interested in only very small portions of the interval this assumption is meaningful). This means that the expected number of events in each of the n subintervals is equal to

Now we assume that the occurrence of an event in the whole interval can be seen as a sequence of n Bernoulli trials, where the -th Bernoulli trial corresponds to looking whether an event happens at the subinterval with probability The expected number of total events in such trials would be the expected number of total events in the whole interval. Hence for each subdivision of the interval we have approximated the occurrence of the event as a Bernoulli process of the form As we have noted before we want to consider only very small subintervals. Therefore, we take the limit as goes to infinity.

In this case the binomial distribution converges to what is known as the Poisson distribution by the Poisson limit theorem.

In several of the above examples — such as the number of mutations in a given sequence of DNA — the events being counted are actually the outcomes of discrete trials, and would more precisely be modelled using the binomial distribution, that is

In such cases n is very large and p is very small (and so the expectation np is of intermediate magnitude). Then the distribution may be approximated by the less cumbersome Poisson distribution

This approximation is sometimes known as the law of rare events,[72]: 5 since each of the n individual Bernoulli events rarely occurs.

The name "law of rare events" may be misleading because the total count of success events in a Poisson process need not be rare if the parameter np is not small. For example, the number of telephone calls to a busy switchboard in one hour follows a Poisson distribution with the events appearing frequent to the operator, but they are rare from the point of view of the average member of the population who is very unlikely to make a call to that switchboard in that hour.

The variance of the binomial distribution is 1 − p times that of the Poisson distribution, so almost equal when p is very small.

The word law is sometimes used as a synonym of probability distribution, and convergence in law means convergence in distribution. Accordingly, the Poisson distribution is sometimes called the "law of small numbers" because it is the probability distribution of the number of occurrences of an event that happens rarely but has very many opportunities to happen. The Law of Small Numbers is a book by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz about the Poisson distribution, published in 1898.[12][73]

Poisson point process

[edit]The Poisson distribution arises as the number of points of a Poisson point process located in some finite region. More specifically, if D is some region space, for example Euclidean space Rd, for which |D|, the area, volume or, more generally, the Lebesgue measure of the region is finite, and if N(D) denotes the number of points in D, then

Poisson regression and negative binomial regression

[edit]Poisson regression and negative binomial regression are useful for analyses where the dependent (response) variable is the count (0, 1, 2, ... ) of the number of events or occurrences in an interval.

Biology

[edit]The Luria–Delbrück experiment tested against the hypothesis of Lamarckian evolution, which should result in a Poisson distribution.

Katz and Miledi measured the membrane potential with and without the presence of acetylcholine (ACh).[74] When ACh is present, ion channels on the membrane would be open randomly at a small fraction of the time. As there are a large number of ion channels each open for a small fraction of the time, the total number of ion channels open at any moment is Poisson distributed. When ACh is not present, effectively no ion channels are open. The membrane potential is . Subtracting the effect of noise, Katz and Miledi found the mean and variance of membrane potential to be and respectively, giving . (pp. 94-95[75])

During each cellular replication event, the number of mutations is roughly Poisson distributed.[76] For example, the HIV virus has 10,000 base pairs, and has a mutation rate of about 1 per 30,000 base pairs, meaning the number of mutations per replication event is distributed as . (p. 64[75])

Other applications in science

[edit]In a Poisson process, the number of observed occurrences fluctuates about its mean λ with a standard deviation These fluctuations are denoted as Poisson noise or (particularly in electronics) as shot noise.

The correlation of the mean and standard deviation in counting independent discrete occurrences is useful scientifically. By monitoring how the fluctuations vary with the mean signal, one can estimate the contribution of a single occurrence, even if that contribution is too small to be detected directly. For example, the charge e on an electron can be estimated by correlating the magnitude of an electric current with its shot noise. If N electrons pass a point in a given time t on the average, the mean current is ; since the current fluctuations should be of the order (i.e., the standard deviation of the Poisson process), the charge can be estimated from the ratio [citation needed]

An everyday example is the graininess that appears as photographs are enlarged; the graininess is due to Poisson fluctuations in the number of reduced silver grains, not to the individual grains themselves. By correlating the graininess with the degree of enlargement, one can estimate the contribution of an individual grain (which is otherwise too small to be seen unaided).[citation needed]

In causal set theory the discrete elements of spacetime follow a Poisson distribution in the volume.

The Poisson distribution also appears in quantum mechanics, especially quantum optics. Namely, for a quantum harmonic oscillator system in a coherent state, the probability of measuring a particular energy level has a Poisson distribution.

Computational methods

[edit]The Poisson distribution poses two different tasks for dedicated software libraries: evaluating the distribution , and drawing random numbers according to that distribution.

Evaluating the Poisson distribution

[edit]Computing for given and is a trivial task that can be accomplished by using the standard definition of in terms of exponential, power, and factorial functions. However, the conventional definition of the Poisson distribution contains two terms that can easily overflow on computers: λk and k!. The fraction of λk to k! can also produce a rounding error that is very large compared to e−λ, and therefore give an erroneous result. For numerical stability the Poisson probability mass function should therefore be evaluated as

which is mathematically equivalent but numerically stable. The natural logarithm of the Gamma function can be obtained using the lgamma function in the C standard library (C99 version) or R, the gammaln function in MATLAB or SciPy, or the log_gamma function in Fortran 2008 and later.

Some computing languages provide built-in functions to evaluate the Poisson distribution, namely

- R: function

dpois(x, lambda); - Excel: function

POISSON( x, mean, cumulative), with a flag to specify the cumulative distribution; - Mathematica: univariate Poisson distribution as

PoissonDistribution[],[77] bivariate Poisson distribution asMultivariatePoissonDistribution[{ }],.[78]

Random variate generation

[edit]The less trivial task is to draw integer random variate from the Poisson distribution with given

Solutions are provided by:

- R: function

rpois(n, lambda); - GNU Scientific Library (GSL): function gsl_ran_poisson

A simple algorithm to generate random Poisson-distributed numbers (pseudo-random number sampling) has been given by Knuth:[79]: 137-138

algorithm poisson random number (Knuth):

init:

Let L ← e−λ, k ← 0 and p ← 1.

do:

k ← k + 1.

Generate uniform random number u in [0,1] and let p ← p × u.

while p > L.

return k − 1.

The complexity is linear in the returned value k, which is λ on average. There are many other algorithms to improve this. Some are given in Ahrens & Dieter, see § References below.

For large values of λ, the value of L = e−λ may be so small that it is hard to represent. This can be solved by a change to the algorithm which uses an additional parameter STEP such that e−STEP does not underflow: [citation needed]

algorithm poisson random number (Junhao, based on Knuth):

init:

Let λLeft ← λ, k ← 0 and p ← 1.

do:

k ← k + 1.

Generate uniform random number u in (0,1) and let p ← p × u.

while p < 1 and λLeft > 0:

if λLeft > STEP:

p ← p × eSTEP

λLeft ← λLeft − STEP

else:

p ← p × eλLeft

λLeft ← 0

while p > 1.

return k − 1.

The choice of STEP depends on the threshold of overflow. For double precision floating point format the threshold is near e700, so 500 should be a safe STEP.

Other solutions for large values of λ include rejection sampling and using Gaussian approximation.

Inverse transform sampling is simple and efficient for small values of λ, and requires only one uniform random number u per sample. Cumulative probabilities are examined in turn until one exceeds u.

algorithm Poisson generator based upon the inversion by sequential search:[80]: 505 init: Let x ← 0, p ← e−λ, s ← p. Generate uniform random number u in [0,1]. while u > s do: x ← x + 1. p ← p × λ / x. s ← s + p. return x.

See also

[edit]- Binomial distribution

- Compound Poisson distribution

- Conway–Maxwell–Poisson distribution

- Erlang distribution

- Exponential distribution

- Gamma distribution

- Hermite distribution

- Index of dispersion

- Negative binomial distribution

- Poisson clumping

- Poisson point process

- Poisson regression

- Poisson sampling

- Poisson wavelet

- Queueing theory

- Renewal theory

- Robbins lemma

- Skellam distribution

- Tweedie distribution

- Zero-inflated model

- Zero-truncated Poisson distribution

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Haight, Frank A. (1967). Handbook of the Poisson Distribution. New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-33932-8.

- ^ a b Yates, Roy D.; Goodman, David J. (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes: A Friendly Introduction for Electrical and Computer Engineers (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-45259-1.

- ^ Ross, Sheldon M. (2014). Introduction to Probability Models (11th ed.). Academic Press.

- ^ Poisson, Siméon D. (1837). Probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile, précédées des règles générales du calcul des probabilités [Research on the Probability of Judgments in Criminal and Civil Matters] (in French). Paris, France: Bachelier.

- ^ de Moivre, Abraham (1711). "De mensura sortis, seu, de probabilitate eventuum in ludis a casu fortuito pendentibus" [On the Measurement of Chance, or, on the Probability of Events in Games Depending Upon Fortuitous Chance]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (in Latin). 27 (329): 213–264. doi:10.1098/rstl.1710.0018.

- ^ de Moivre, Abraham. The Doctrine of Chances: Or, A Method of Calculating the Probability of Events in Play. London, Great Britain: W. Pearson. ISBN 9780598843753.

- ^ de Moivre, Abraham. "Of the Laws of Chance". In Motte, Benjamin (ed.). The Philosophical Transactions from the Year MDCC (where Mr. Lowthorp Ends) to the Year MDCCXX. Abridg'd, and Dispos'd Under General Heads (in Latin). Vol. I. London, Great Britain: R. Wilkin, R. Robinson, S. Ballard, W. and J. Innys, and J. Osborn. pp. 190–219.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Johnson, Norman L.; Kemp, Adrienne W.; Kotz, Samuel (2005). "Poisson Distribution". Univariate Discrete Distributions (3rd ed.). New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 156–207. doi:10.1002/0471715816. ISBN 978-0-471-27246-5.

- ^ Stigler, Stephen M. (1982). "Poisson on the Poisson Distribution". Statistics & Probability Letters. 1 (1): 33–35. doi:10.1016/0167-7152(82)90010-4.

- ^ Hald, Anders; de Moivre, Abraham; McClintock, Bruce (1984). "A. de Moivre: 'De Mensura Sortis' or 'On the Measurement of Chance'". International Statistical Review / Revue Internationale de Statistique. 52 (3): 229–262. doi:10.2307/1403045. JSTOR 1403045.

- ^ Newcomb, Simon (1860). "Notes on the theory of probabilities". The Mathematical Monthly. 2 (4): 134–140.

- ^ a b c

von Bortkiewitsch, Ladislaus (1898). Das Gesetz der kleinen Zahlen [The law of small numbers] (in German). Leipzig, Germany: B.G. Teubner. pp. 1, 23–25.

- On page 1, Bortkiewicz presents the Poisson distribution.

- On pages 23–25, Bortkiewitsch presents his analysis of "4. Beispiel: Die durch Schlag eines Pferdes im preußischen Heere Getöteten." [4. Example: Those killed in the Prussian army by a horse's kick.]

- ^ For the proof, see: Proof wiki: expectation and Proof wiki: variance

- ^ Kardar, Mehran (2007). Statistical Physics of Particles. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-87342-0. OCLC 860391091.

- ^ Dekking, Frederik Michel; Kraaikamp, Cornelis; Lopuhaä, Hendrik Paul; Meester, Ludolf Erwin (2005). A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics. Springer Texts in Statistics. p. 167. doi:10.1007/1-84628-168-7. ISBN 978-1-85233-896-1.

- ^ Pitman, Jim (1993). Probability. Springer Texts in Statistics. New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London: Springer. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-387-94594-1.

- ^ Hsu, Hwei P. (1996). Theory and Problems of Probability, Random Variables, and Random Processes. Schaum's Outline Series. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 68. ISBN 0-07-030644-3.

- ^ Arfken, George B.; Weber, Hans J. (2005). Mathematical Methods for Physicists Sixth Edition. Elsevier Academic Press. p. 1131. ISBN 0-12-059876-0.

- ^ Cowan, Glen (2009). "Derivation of the Poisson distribution" (PDF).

- ^ Joyce, D. (2014). "The Poisson process" (PDF).

- ^ Ugarte, M.D.; Militino, A.F.; Arnholt, A.T. (2016). Probability and Statistics with R (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL, US: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-0439-4.

- ^ Helske, Jouni (2017). "KFAS: Exponential Family State Space Models in R". Journal of Statistical Software. 78 (10). arXiv:1612.01907. doi:10.18637/jss.v078.i10. S2CID 14379617.

- ^ Choi, Kwok P. (1994). "On the medians of gamma distributions and an equation of Ramanujan". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 121 (1): 245–251. doi:10.2307/2160389. JSTOR 2160389.

- ^ Riordan, John (1937). "Moment Recurrence Relations for Binomial, Poisson and Hypergeometric Frequency Distributions" (PDF). Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 8 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177732430. JSTOR 2957598.

- ^ D. Ahle, Thomas (2022). "Sharp and simple bounds for the raw moments of the Binomial and Poisson distributions". Statistics & Probability Letters. 182 109306. arXiv:2103.17027. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2021.109306.

- ^ Lehmann, Erich Leo (1986). Testing Statistical Hypotheses (2nd ed.). New York, NJ, US: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-94919-2.

- ^ Raikov, Dmitry (1937). "On the decomposition of Poisson laws". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de l'URSS. 14: 9–11.

- ^ von Mises, Richard. Mathematical Theory of Probability and Statistics. New York: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/C2013-0-12460-9. ISBN 978-1-4832-3213-3.

- ^ Harremoes, P. (July 2001). "Binomial and Poisson distributions as maximum entropy distributions". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 47 (5): 2039–2041. doi:10.1109/18.930936. S2CID 16171405.

- ^ Laha, Radha G.; Rohatgi, Vijay K. (1979). Probability Theory. New York, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-03262-5.

- ^ Mitzenmacher, Michael (2017). Probability and computing: Randomization and probabilistic techniques in algorithms and data analysis. Eli Upfal (2nd ed.). Exercise 5.14. ISBN 978-1-107-15488-9. OCLC 960841613.

- ^ a b Mitzenmacher, Michael; Upfal, Eli (2005). Probability and Computing: Randomized Algorithms and Probabilistic Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83540-4.

- ^ Short, Michael (2013). "Improved Inequalities for the Poisson and Binomial Distribution and Upper Tail Quantile Functions". ISRN Probability and Statistics. 2013. Corollary 6. doi:10.1155/2013/412958.

- ^ Short, Michael (2013). "Improved Inequalities for the Poisson and Binomial Distribution and Upper Tail Quantile Functions". ISRN Probability and Statistics. 2013. Theorem 2. doi:10.1155/2013/412958.

- ^ Kamath, Govinda M.; Şaşoğlu, Eren; Tse, David (14–19 June 2015). Optimal haplotype assembly from high-throughput mate-pair reads. 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT). Hong Kong, China. pp. 914–918. arXiv:1502.01975. doi:10.1109/ISIT.2015.7282588. S2CID 128634.

- ^ Prins, Jack (2012). "6.3.3.1. Counts Control Charts". e-Handbook of Statistical Methods. NIST/SEMATECH. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Feller, William. An Introduction to Probability Theory and its Applications.

- ^ Zhang, Huiming; Liu, Yunxiao; Li, Bo (2014). "Notes on discrete compound Poisson model with applications to risk theory". Insurance: Mathematics and Economics. 59: 325–336. doi:10.1016/j.insmatheco.2014.09.012.

- ^ Zhang, Huiming; Li, Bo (2016). "Characterizations of discrete compound Poisson distributions". Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 45 (22): 6789–6802. doi:10.1080/03610926.2014.901375. S2CID 125475756.

- ^ McCullagh, Peter; Nelder, John (1989). Generalized Linear Models. Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability. Vol. 37. London, UK: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-31760-6.

- ^ Anscombe, Francis J. (1948). "The transformation of Poisson, binomial and negative binomial data". Biometrika. 35 (3–4): 246–254. doi:10.1093/biomet/35.3-4.246. JSTOR 2332343.

- ^ Ross, Sheldon M. (2010). Introduction to Probability Models (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-375686-2.

- ^ "1.7.7 – Relationship between the Multinomial and Poisson | STAT 504". Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Loukas, Sotirios; Kemp, C. David (1986). "The Index of Dispersion Test for the Bivariate Poisson Distribution". Biometrics. 42 (4): 941–948. doi:10.2307/2530708. JSTOR 2530708.

- ^ Free Random Variables by D. Voiculescu, K. Dykema, A. Nica, CRM Monograph Series, American Mathematical Society, Providence RI, 1992

- ^ Alexandru Nica, Roland Speicher: Lectures on the Combinatorics of Free Probability. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, Vol. 335, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- ^ Lectures on the Combinatorics of Free Probability by A. Nica and R. Speicher, pp. 203–204, Cambridge Univ. Press 2006

- ^ Paszek, Ewa. "Maximum likelihood estimation – examples". cnx.org.

- ^ Van Trees, Harry L. (2013). Detection estimation and modulation theory. Kristine L. Bell, Zhi Tian (Second ed.). ISBN 978-1-299-66515-6. OCLC 851161356.

- ^ Garwood, Frank (1936). "Fiducial Limits for the Poisson Distribution". Biometrika. 28 (3/4): 437–442. doi:10.1093/biomet/28.3-4.437. JSTOR 2333958.

- ^ Breslow, Norman E.; Day, Nick E. (1987). Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Vol. 2 — The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 978-92-832-0182-3. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Fink, Daniel (1997). A Compendium of Conjugate Priors.

- ^ Dytso, Alex; Poor, H. Vincent (2020). "Estimation in Poisson noise: Properties of the conditional mean estimator". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 66 (7): 4304–4323. arXiv:1911.03744. doi:10.1109/TIT.2020.2979978. S2CID 207853178.

- ^ Gelman; Carlin, John B.; Stern, Hal S.; Rubin, Donald B. (2003). Bayesian Data Analysis (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL, US: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-388-X.

- ^ Clevenson, M. Lawrence; Zidek, James V. (1975). "Simultaneous estimation of the means of independent Poisson laws". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 70 (351): 698–705. doi:10.1080/01621459.1975.10482497. JSTOR 2285958.

- ^ Berger, James O. (1985). Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian Analysis. Springer Series in Statistics (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. Bibcode:1985sdtb.book.....B. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4286-2. ISBN 978-0-387-96098-2.

- ^ Rasch, Georg (1963). The Poisson Process as a Model for a Diversity of Behavioural Phenomena (PDF). 17th International Congress of Psychology. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/e685262012-108.

- ^ Flory, Paul J. (1940). "Molecular Size Distribution in Ethylene Oxide Polymers". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 62 (6): 1561–1565. Bibcode:1940JAChS..62.1561F. doi:10.1021/ja01863a066.

- ^ Dwyer, Barry (23 March 2016). Systems Analysis and Synthesis: Bridging Computer Science and Information Technology. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-805449-9.

Similarly, if candidates arrive at an enrolment center uniformly, the times between their arrivals will be distributed exponentially, and the number of candidates arriving each hour will follow a Poisson distribution.

- ^ Lomnitz, Cinna (1994). Fundamentals of Earthquake Prediction. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-57419-8. OCLC 647404423.

- ^ "Poisson Distribution and Radiological Measurement". www.hko.gov.hk. Retrieved 30 September 2025.

The actual number of decays over a period of time is generally described by the Poisson distribution.

- ^ a student (1907). "On the error of counting with a haemacytometer". Biometrika. 5 (3): 351–360. doi:10.2307/2331633. JSTOR 2331633.

- ^ Boland, Philip J. (1984). "A biographical glimpse of William Sealy Gosset". The American Statistician. 38 (3): 179–183. doi:10.1080/00031305.1984.10483195. JSTOR 2683648.

- ^ Erlang, Agner K. (1909). "Sandsynlighedsregning og Telefonsamtaler" [Probability Calculation and Telephone Conversations]. Nyt Tidsskrift for Matematik (in Danish). 20 (B): 33–39. JSTOR 24528622.

- ^ Hornby, Dave (2014). "Football Prediction Model: Poisson Distribution". Sports Betting Online. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Campbell, Michael J.; Jacques, Richard M. (13 February 2023). Statistics at Square Two. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-40136-0.

The expected values are given by the Poisson model.

- ^ Koyama, Kento; Hokunan, Hidekazu; Hasegawa, Mayumi; Kawamura, Shuso; Koseki, Shigenobu (2016). "Do bacterial cell numbers follow a theoretical Poisson distribution? Comparison of experimentally obtained numbers of single cells with random number generation via computer simulation". Food Microbiology. 60: 49–53. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2016.05.019. PMID 27554145.

- ^ The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference. Academic Press. 30 September 2020. ISBN 978-0-12-805409-3.

The division of light into discrete photons means that nominally constant light sources – e.g. a light bulb or a reflecting object in a scene – will produce visual inputs that vary randomly over time. These variations are described by Poisson statistics.

- ^ Clarke, R. D. (1946). "An application of the Poisson distribution" (PDF). Journal of the Institute of Actuaries. 72 (3): 481. doi:10.1017/S0020268100035435.

- ^ Hardy, Godfrey H.; Littlewood, John E. (1923). "On some problems of "partitio numerorum" III: On the expression of a number as a sum of primes". Acta Mathematica. 44: 1–70. doi:10.1007/BF02403921.

- ^ Gallagher, Patrick X. (1976). "On the distribution of primes in short intervals". Mathematika. 23 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1112/s0025579300016442.

- ^ Cameron, A. Colin; Trivedi, Pravin K. (1998). Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63567-7.

- ^ Edgeworth, F.Y. (1913). "On the use of the theory of probabilities in statistics relating to society". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 76 (2): 165–193. doi:10.2307/2340091. JSTOR 2340091.

- ^ Katz, B.; Miledi, R. (August 1972). "The statistical nature of the acetylcholine potential and its molecular components". The Journal of Physiology. 224 (3): 665–699. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009918. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 1331515. PMID 5071933.

- ^ a b Nelson, Philip Charles; Bromberg, Sarina; Hermundstad, Ann; Prentice, Jason (2015). Physical models of living systems. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Company, a Macmillan Education Imprint. ISBN 978-1-4641-4029-7. OCLC 891121698.

- ^ Foster, Patricia L. (1 January 2006), "Methods for Determining Spontaneous Mutation Rates", DNA Repair, Part B, Methods in Enzymology, vol. 409, Academic Press, pp. 195–213, doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09012-9, ISBN 978-0-12-182814-1, PMC 2041832, PMID 16793403

- ^ "Wolfram Language: PoissonDistribution reference page". wolfram.com. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Wolfram Language: MultivariatePoissonDistribution reference page". wolfram.com. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Knuth, Donald Ervin (1997). Seminumerical Algorithms. The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-89684-8.

- ^ Devroye, Luc (1986). "Discrete Univariate Distributions" (PDF). Non-Uniform Random Variate Generation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. pp. 485–553. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8643-8_10. ISBN 978-1-4613-8645-2.

Sources

[edit]- Ahrens, Joachim H.; Dieter, Ulrich (1974). "Computer Methods for Sampling from Gamma, Beta, Poisson and Binomial Distributions". Computing. 12 (3): 223–246. doi:10.1007/BF02293108. S2CID 37484126.

- Ahrens, Joachim H.; Dieter, Ulrich (1982). "Computer Generation of Poisson Deviates". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 8 (2): 163–179. doi:10.1145/355993.355997. S2CID 12410131.

- Evans, Ronald J.; Boersma, J.; Blachman, N. M.; Jagers, A. A. (1988). "The Entropy of a Poisson Distribution: Problem 87-6". SIAM Review. 30 (2): 314–317. doi:10.1137/1030059.

Poisson distribution

View on Grokipediawhere is a non-negative integer (0, 1, 2, ...), is the base of the natural logarithm (approximately 2.71828), and .[2] Named after the French mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson, the distribution was introduced in his 1837 work Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile, where it arose as an approximation to the binomial distribution for large numbers of trials with small success probabilities./05:_Discrete_Probability_Distributions/5.06:_Poisson_Distribution) An early empirical demonstration came from statistician Ladislaus Bortkiewicz in 1898, who applied it to analyze the frequency of horse-kick deaths among Prussian army officers, showing a close fit to the observed data.[3] The distribution's mode is the largest integer less than or equal to λ (or both λ and λ-1 if λ is an integer), and its cumulative distribution function lacks a simple closed form, often requiring numerical computation.[1] Key assumptions for the Poisson distribution include that events are independent, the average rate λ remains constant over the interval, and the probability of more than one event in a very small subinterval is negligible.[3] It approximates the binomial distribution when the number of trials n is large and the success probability p is small such that np = λ is fixed, providing a simpler model for count data.[2] In practice, the maximum likelihood estimator for λ is the sample mean of the observed counts.[1] The Poisson distribution finds wide applications in fields like queueing theory for modeling customer arrivals, reliability engineering for defect counts, and epidemiology for disease incidence rates, as well as in finance for predicting rare events like stock trades.[2] It extends to generalized forms, such as the compound Poisson distribution for summed random variables, and serves as the basis for Poisson regression in analyzing count-based outcomes in generalized linear models.[3]

History and Motivation

Historical Development

The Poisson distribution has roots in early attempts to approximate binomial probabilities under conditions of rare events. In 1711, Abraham de Moivre provided an approximation for the binomial distribution when the probability of success is small and the number of trials is large, yielding where . This formula, derived in his work De Mensura Sortis seu; de Probabilitate Eventuum in Ludis a Casibus Dependentium, effectively described the distribution of rare occurrences, though de Moivre did not explicitly recognize it as a distinct limiting form.[4] The distribution was formally introduced by Siméon Denis Poisson in 1837 as part of his treatise Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile, where he derived it as a limit of the binomial distribution and termed it the "law of small numbers" to model infrequent events in legal and social contexts. Poisson's derivation emphasized its application to probabilistic judgments in jury decisions and civil matters, establishing it as a tool for analyzing sparse data.[5] Its adoption as a practical statistical tool gained prominence in the late 19th century through Ladislaus Bortkiewicz's 1898 monograph Das Gesetz der kleinen Zahlen, which applied Poisson's law to empirical data, including the famous analysis of deaths from horse kicks in the Prussian army (1875–1894), demonstrating close fits between observed frequencies and theoretical predictions. This work popularized the distribution among statisticians for rare event modeling. The term "Poisson distribution" emerged in the early 20th century, honoring Poisson despite de Moivre's precursor contributions.[6] By the mid-20th century, the distribution evolved into a foundational element of stochastic processes, with the Poisson process formalized in the 1940s by figures like William Feller, enabling its use in modeling continuous-time random events such as arrivals in queueing theory and point processes.[7]Derivation from Binomial Limit

The binomial distribution describes the number of successes in a fixed number of independent Bernoulli trials, each with success probability . The probability mass function (PMF) for a binomial random variable is given by [8] To derive the Poisson distribution, consider the limit as the number of trials and the success probability , while keeping the expected number of successes fixed and finite. This scenario models rare events, where successes are infrequent but the total rate remains constant.[9] Substitute into the binomial PMF: Rewrite the binomial coefficient as As , the term for fixed , since each factor for . Additionally, by the standard limit definition of the exponential function, and . Thus, which is the PMF of the Poisson distribution with parameter : A more rigorous expansion for the binomial coefficient can use Stirling's approximation , but the direct limit suffices for fixed .[8][9] This derivation interprets the Poisson distribution as arising from many trials with infinitesimally small success probabilities, such as modeling events in small time intervals or spatial units where occurrences are rare but aggregate to a fixed rate . For example, the number of successes in trials each with success probability approximates a random variable when is large.[10]Definition

Probability Mass Function

The Poisson distribution is a discrete probability distribution that expresses the probability of a given number of events occurring in a fixed interval of time or space if these events occur with a known constant mean rate and independently of the time since the last event. The probability mass function (PMF) for a Poisson random variable with parameter is given by for , and for .[10][11] The support of the distribution is the set of non-negative integers, reflecting its application to counting discrete events.[10] The term serves as the normalizing constant, ensuring that the infinite sum of probabilities equals 1, since , so .[12] The probabilities satisfy a recursive relation: for .[13] The shape of the PMF is right-skewed for small values of (e.g., ), with the mode at 0 or nearby integers, and becomes approximately symmetric as increases (e.g., ), though it remains slightly skewed.[14]Parameter and Support

The Poisson distribution is parameterized by a single positive real number λ, which represents the average rate of occurrence of events within a fixed unit interval, such as time or space, and serves as both the mean and variance of the distribution.[1] This parameter λ quantifies the expected number of events in that interval, making it essential for modeling rare or random events like arrivals or defects.[15] For the distribution to be well-defined, λ must be strictly greater than zero; as λ approaches 0, the probability mass concentrates entirely at zero, reflecting scenarios with negligible event likelihood.[1] Conversely, as λ tends to infinity, the distribution approximates a normal distribution via the central limit theorem, useful for large-scale event modeling.[15] The support of the Poisson random variable X is the set of non-negative integers, denoted as , which aligns with its application to count data where negative or fractional values are impossible.[1] This discrete domain ensures the distribution captures whole-number occurrences, such as the number of emails received in an hour.[15] Regarding units, λ is dimensionless when modeling pure counts but can be scaled to represent rates, for instance, events per hour or per square kilometer, depending on the context of the unit interval.[1] A notable special case occurs when λ = 1, where the probability of zero events is , illustrating the likelihood of no occurrences in an interval expected to have exactly one event on average.[15]Properties

Moments and Central Tendency

The Poisson distribution, denoted as where is the rate parameter, exhibits several key measures of central tendency and dispersion that characterize its shape and behavior. The expected value, or mean, of a Poisson random variable is exactly equal to its parameter , reflecting the average number of events in the fixed interval. This property arises directly from the probability mass function and underscores the distribution's role in modeling count data with a stable long-run average. The variance of is also , a hallmark feature known as equidispersion, where the spread of the distribution matches its central tendency. This equality implies that the standard deviation is , and it distinguishes the Poisson from overdispersed alternatives like the negative binomial distribution. In practical applications, such as queueing theory or rare event modeling, this variance-mean equality facilitates straightforward statistical inference without additional parameters. For measures of central tendency beyond the mean, the mode of the Poisson distribution—the value with the highest probability—depends on whether is an integer. If is not an integer, the mode is uniquely ; if is an integer, both and are modes, each with equal probability. This unimodal structure, peaking near , aligns with the distribution's asymmetry for small and near-symmetry for large . The median, which divides the probability mass into two equal parts, is typically for most values, though a refined approximation for large is [16], providing a more precise central location in asymptotic analyses. These location parameters highlight the Poisson's utility in discrete settings where exact counts matter, such as in ecology for species abundance. Regarding higher-order moments, the skewness of the Poisson distribution is , indicating right-skewness that diminishes as increases, approaching zero for large and resembling a normal distribution. This decreasing skewness explains the distribution's transition from a highly asymmetric form (e.g., for , skewness ≈ 1) to near-symmetry (e.g., for , skewness ≈ 0.1), a property exploited in central limit theorem applications for Poisson approximations. Complementing this, the coefficient of variation—defined as the standard deviation divided by the mean—is , which similarly decreases with , quantifying the relative variability and aiding comparisons across different rate scales in fields like reliability engineering. These moments can be derived using the probability generating function, though their direct computation from the mass function confirms their parameter dependence.Generating Functions

The probability generating function (PGF) of a Poisson random variable with parameter is defined as for , and it equals .[17] This form arises from substituting the probability mass function into the expectation: The PGF encapsulates the distribution's probabilities and facilitates analysis of sums of independent Poissons.[17] The moment generating function (MGF) of is for , given by .[18] It is derived similarly: Moments of are obtained by evaluating derivatives of the MGF at ; for instance, the first derivative yields .[18] Higher-order derivatives provide further moments, confirming properties like the raw moments through successive differentiation.[18] The cumulant generating function is the natural logarithm of the MGF, .[19] Its Taylor series expansion around has coefficients that are the cumulants of , and for the Poisson, all cumulants equal .[19] In particular, the first cumulant is the mean , and the second cumulant is the variance , establishing the equidispersion property where variance equals the mean.[19]Sums of Independent Variables

A fundamental property of the Poisson distribution is its closure under addition for independent random variables. Specifically, if are independent random variables where for , then their sum follows a Poisson distribution with parameter .[17] This result can be proved using probability generating functions (PGFs). The PGF of a random variable is . Since the are independent, the PGF of is the product of the individual PGFs: which is the PGF of a random variable.[17] This property extends naturally to Poisson processes. The superposition of independent Poisson processes with rates —that is, the combined process counting events from all sources—is itself a Poisson process with rate .[20] For example, consider defects in manufactured items arising from multiple independent sources, such as different production stages, each modeled as a Poisson process with rate . The total number of defects observed follows a Poisson distribution with parameter equal to the sum of the individual rates, facilitating aggregated quality control analysis.[21]Inequality and Tail Bounds

The Poisson distribution exhibits strong concentration properties around its mean , making it amenable to tail bounds that quantify the probability of deviations. Concentration inequalities such as Chernoff bounds provide exponential upper bounds on these tail probabilities, leveraging the moment generating function for . For the upper tail, a standard Chernoff bound states that for , This bound is derived by optimizing the Chernoff parameter and is widely used due to its simplicity and tightness for moderate . A more precise form, without simplification, is for , obtained by minimizing over .[22] For the lower tail, the Chernoff bound yields for . This follows from applying Markov's inequality to with , providing an exponential decay that mirrors the upper tail but with a slightly looser constant. These bounds highlight the sub-Gaussian-like behavior of the Poisson despite its unbounded support.[22] Hoeffding's inequality, originally for bounded independent random variables, adapts to the Poisson distribution via its representation as a limit of binomials or through direct moment bounds. An improved version tightens the Chernoff-Hoeffding bound by a factor of at least two, yielding exponential upper tail estimates of the form for and , where is the standard normal CDF and relates to the tail probability. This adaptation enhances applicability in scenarios requiring uniform bounds across parameters.[23] For the upper tail, Stirling's approximation facilitates computable bounds, particularly for large . A practical upper bound is , which is numerically stable and avoids overflow for large . More refined Stirling-based estimates incorporate normal approximations for near-median tails, such as for and , bridging local and global tail behavior.[24] These inequalities underpin large deviations theory for the Poisson distribution, where the rate function governs the exponential decay for . In rare event modeling, such as queueing systems or risk assessment, these bounds enable precise estimation of overflow probabilities, with applications to Poisson approximations in compound processes ensuring asymptotic equivalence under factorial cumulant constraints. For instance, in estimating large deviations for sums approximating Poissons, the relative error is controlled by terms like , where bounds higher moments.[25]Related Distributions and Processes

Connection to Binomial Distribution

The Poisson distribution with parameter arises as a limiting case of the binomial distribution when the number of trials is large, the success probability is small, and the product is held fixed. In this regime, the probability mass function of the binomial converges pointwise to that of the Poisson, providing an exact limit in the sense of distribution. Conversely, the binomial can be viewed as a finite- approximation to the Poisson when modeling scenarios with many independent rare events. A notable instance is when , with and large , where the probability of zero successes in the binomial is , matching for the Poisson. This result is significant in random allocation models, such as throwing balls into bins uniformly at random, where the probability a given bin receives zero balls approaches .[26][27] The quality of this approximation is quantified by the total variation distance . A simple bound is , which scales as .[27] A practical rule of thumb for employing the Poisson approximation is to use it when and , ensuring the conditions of large and small are met for reasonable accuracy. For instance, in manufacturing quality control, the number of defective items in a large batch of products, each with a small defect probability , follows approximately a distribution; an example is inspecting 1000 light bulbs with a 0.1% defect rate, where and the Poisson simplifies computations for rare defects.[28][29]Role in Poisson Point Processes

The Poisson point process provides a fundamental framework in stochastic geometry where the Poisson distribution arises as the marginal law governing point counts. In a homogeneous Poisson point process defined on a space such as with constant intensity , the number of points falling within any bounded region of finite measure (such as area in two dimensions or volume in three) follows a Poisson distribution with parameter .[30] This means the probability of observing exactly points in is given by A key property is the independence of counts across disjoint regions: if are mutually disjoint bounded sets, then the random variables are independent, each Poisson-distributed with parameters .[31] This construction generalizes to the inhomogeneous Poisson point process, where the intensity varies with location . Here, the number of points in a bounded region is Poisson-distributed with mean equal to the integrated intensity , reflecting the expected total "rate" over the region.[30] Counts in disjoint regions remain independent under this setup. In the temporal setting, where the process models events over time, the homogeneous case reduces to the classic Poisson process, a renewal process with exponential interarrival times; the number of arrivals in a fixed interval of length is then Poisson().[32] The connection extends to spatial statistics, where Poisson point processes serve as null models for analyzing point patterns in fields like ecology and epidemiology, assuming complete spatial randomness.[30] Additionally, these processes underpin shot noise models, originally developed to describe fluctuations in electrical currents due to discrete electron emissions, as introduced by Norman Campbell in his studies of thermionic noise.[33] Superposition of independent Poisson point processes yields another Poisson point process with intensity equal to the sum of the individual intensities.[31]Generalizations and Variants

The bivariate Poisson distribution provides a natural extension of the univariate Poisson distribution to model pairs of correlated count variables, such as the number of events occurring in two related processes. It is constructed by letting and , where , , and are independent Poisson random variables with parameters , , and , respectively; the shared component induces positive correlation between and . The marginal distributions of and are Poisson with means and , while the correlation coefficient is . This model is particularly useful for bivariate count data exhibiting dependence, such as insurance claims in multiple categories or sports match outcomes. In football (soccer), the bivariate Poisson distribution is used to model the joint distribution of goals scored by the two competing teams, which are marginally distributed as univariate Poisson random variables but exhibit correlation due to shared match dynamics and team interactions; this allows for improved prediction of match results by accounting for the dependence between the teams' goal counts.[34][35][36][37] The construction was first detailed by Holgate in 1964, with further developments in estimation and applications appearing in subsequent works.[34][35] The negative binomial distribution arises as a key overdispersed generalization of the Poisson distribution, accommodating scenarios where the variance exceeds the mean, which is common in real-world count data due to unobserved heterogeneity or clustering. Parameterized by mean and dispersion parameter , it has probability mass function for , yielding mean and variance . As , the distribution converges to the Poisson with parameter , while smaller increases overdispersion. This makes it a flexible alternative for modeling counts like disease incidences or traffic accidents, where Poisson assumptions fail. The negative binomial's role as an overdispersed Poisson variant is extensively analyzed in regression contexts by Cameron and Trivedi (1998). The compound Poisson distribution generalizes the Poisson by considering the total as a random sum , where represents the number of clusters or events, and the are independent and identically distributed positive random variables (independent of ) with probability generating function . The probability generating function of is then which highlights its infinitely divisible nature and utility in aggregating risks. If the are themselves Poisson, follows a Neyman Type A distribution; more generally, it models compound events like total claim amounts in insurance, where counts claims and their sizes. This framework underpins much of actuarial science and stochastic modeling. In non-commutative probability theory, the free Poisson distribution emerges as the free independence analog of the classical Poisson distribution, developed by Voiculescu in the mid-1980s to study operator algebras and random matrices. Unlike the classical case, free probability replaces commuting variables with freely independent non-commuting ones, leading to the free Poisson law—also known as the Marchenko-Pastur distribution—with R-transform for parameter . It arises as the limiting spectral distribution of Wishart matrices and captures "free compounding" effects, with mean and variance . This variant has impacted random matrix theory and free stochastic processes, providing tools for non-commutative limits absent in classical probability. Voiculescu's foundational work (1985) established free probability, with the free Poisson detailed in subsequent developments.[38][39] The Weibull-Poisson distribution extends the Poisson framework by compounding it with a Weibull mixing distribution, yielding a flexible model for survival counts or lifetime data where events follow a non-homogeneous pattern. Defined via the probability generating function or as a Poisson process with Weibull-distributed intensities, it accommodates monotone increasing or decreasing failure rates, making it suitable for analyzing censored count data in reliability engineering or epidemiology, such as recurring failures over time. The resulting distribution has support on non-negative integers and can exhibit under- or overdispersion depending on Weibull shape parameters. This generalization was introduced by Cancho et al. (2011) for competing risks and long-term survival modeling.[40]Parameter Estimation

Maximum Likelihood Estimation

The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for the parameter of a Poisson distribution is derived from a sample of independent and identically distributed observations , each following .[41] The likelihood function is given by [41] To maximize this, consider the log-likelihood [41] which is differentiated with respect to and set to zero: [41] yielding the MLE , the sample mean.[41] This estimator is unbiased, satisfying ,[42] and achieves the Cramér-Rao lower bound, making it the minimum variance unbiased estimator (MVUE).[42] Under standard regularity conditions, the MLE is asymptotically normal: as , [43] For example, if counts of rare events—such as customer arrivals at a service point over fixed time intervals—are observed as , then provides the maximum likelihood estimate of the average arrival rate per interval.[41]Confidence Intervals for λ

Confidence intervals for the parameter λ of a Poisson distribution quantify the uncertainty in estimating the mean rate based on observed counts. For a random sample of n independent observations from a Poisson(λ) distribution, the sample mean is the maximum likelihood estimator for λ, and intervals are typically constructed around an observed value .[44] For large n or large λ, where the central limit theorem applies, a normal approximation provides a simple interval: , with the -quantile of the standard normal distribution. This Wald interval relies on the asymptotic normality of . However, it performs poorly for small n or small λ due to skewness and variance instability. Exact methods avoid approximations by inverting equal-tailed tests using the cumulative distribution function of the Poisson, often leveraging its relationship to the chi-squared distribution. For a single observation , the cumulative probability satisfies , and similarly for the upper tail. The Garwood interval, a central exact method, uses these relations to yield: where is the p-quantile of the chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom. This is conservative, guaranteeing coverage at least . For n observations with total count , apply the formula with k replaced by S to obtain bounds for , then divide by n for λ. This approach is the Poisson analog of the Clopper-Pearson interval for binomial proportions.[44] The discrete nature of the Poisson leads to conservativeness in exact intervals, prompting adjustments like the mid-p method. This subtracts half the probability mass at the observed count from the tail probabilities before inverting the test, producing shorter intervals with expected coverage closer to the nominal without falling below it in most cases. For the Garwood setup, the mid-p lower limit solves , and similarly for the upper. It reduces overcoverage while maintaining good properties. Exact and mid-p intervals tend to be conservative for small λ (e.g., λ < 2), with actual coverage exceeding due to the step function of the discrete cumulative distribution, leading to wider intervals than necessary. Simulations confirm this overcoverage, particularly for low counts, where the Garwood interval's coverage can reach 0.96 or higher for nominal 95%. To address this, simulation-based alternatives, such as parametric bootstrapping or profile likelihood methods, generate empirical intervals tailored to achieve near-nominal coverage and shorter lengths, especially in small-sample settings.[44]Bayesian Inference

Prior and Posterior Distributions