Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Figure skating jumps

View on Wikipedia

| ISU abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| 1Eu | Euler jump |

| T | Toe loop |

| F | Flip |

| Lz | Lutz |

| S | Salchow |

| Lo | Loop |

| A | Axel |

Figure skating jumps are an element of three competitive figure skating disciplines: men's singles, women's singles, and pair skating – but not ice dancing.[a] Jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent".[2] They were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures; many jumps were named after the skaters who invented them or from the figures from which they were developed. Jumps may be performed individually or in combination with each other.

It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, that jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented, and when jumps were formally categorized. In the 1920s, Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice. Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed. Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s. During the post-war period and into the 1950s and early 1960s, triple jumps became more common for both male and female skaters, and a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps had been fully developed. In the 1980s, men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples. By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.

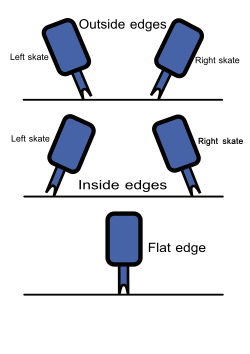

The six most common jumps can be divided into two groups: toe jumps (the toe loop, the flip, and the Lutz) and edge jumps (the Salchow, the loop, and the Axel). The Euler jump, which was known as a half-loop before 2018, is an edge jump. Jumps are also classified by the number of revolutions. Pair skaters perform two types of jumps: side-by-side jumps, in which jumps are accomplished side by side and in unison, and throw jumps, in which the woman performs the jump when assisted and propelled by her partner.

According to the International Skating Union (ISU), jumps must have the following characteristics to earn the most points: they must have "very good height and very good length";[3] they must be executed effortlessly, including the rhythm demonstrated during jump combinations; and they must have good takeoffs and landings. The following are not required, but also taken into consideration: there must be steps executed before the beginning of the jump, or it must have either a creative or unexpected entry; the jump must match the music; and the skater must have, from the jump's takeoff to its landing, a "very good body position".[3] A jump combination is executed when a skater's landing foot of the first jump is also the takeoff foot of the following jump.[4][5] All jumps are considered in the order they are completed. Pair teams, both juniors and seniors, must perform one solo jump during their short programs.

The execution of a jump is divided into eight parts: the set-up, load, transition, pivot, takeoff, flight, landing, and exit. All jumps except the Axel and waltz jumps are taken off while skating backward; Axels and waltz jumps are entered into by skating forward. A skater's body absorbs up to 13–14 g-forces on landing a jump,[6] which may contribute to overuse injuries and stress fractures. Factors such as angular momentum, the moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and the skater's center of mass determine if a jump is successfully completed. Skaters add variations or unusual entries and exits to jumps to increase difficulty.

History

[edit]

According to figure skating historian James R. Hines, jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent".[2] Jumps were viewed as "acrobatic tricks, not as a part of a skater's art"[7] and "had no place"[8] in the skating practices in England during the 19th century, although skaters experimented with jumps from the ice during the last 25 years of the 1800s. Hops, or jumps without rotations, were done for safety reasons, to avoid obstacles, such as hats, barrels, and tree logs, on natural ice.[9][10] In 1881, Spuren Auf Dem Eise ("Tracing on the Ice"), "a monumental publication describing the state of skating in Vienna",[11] briefly mentioned jumps, describing three jumps in two pages.[12] Jumping on skates was a part of the athletic side of free skating and was considered inappropriate for female skaters.[13]

Hines says free skating movements such as spirals, spread eagles, spins, and jumps were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures. For example, Norwegian skater Axel Paulsen, whom Hines calls "progressive",[14] performed the first jump in competition, the Axel, which was named after him, at the first international competition in 1882, as a special figure.[15] Jumps were also related to their corresponding figure; for example, the loop jump. Other jumps, such as the Axel and the Salchow, were named after the skaters who invented them.[7]

It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, when jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented and when jumps were formally categorized. These jumps became elements in athletic free skating programs, but they were not worth more points than no-revolution jumps and half-jumps. In the 1920s, Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice and refine rotations in the Axel.[10] Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed.[16]

Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s.[2][10] Athleticism in the sport increased between the world wars, especially by women like Norwegian world and Olympic champion Sonia Henie, who popularized short skirts which allowed female skaters to maneuver and perform jumps. When international competitions were interrupted by World War II, double jumps by both men and women had become commonplace, and all jumps, except for the Axel, were being doubled.[17][18] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum the development of rotational technique required for Axels and double jumps continued,[19] especially in the United States and Czechoslovakia. Post-war skaters, according to Hines, "pushed the envelope of jumping to extremes that skaters of the 1930s would not have thought possible".[20] For example, world champion Felix Kasper from Austria was well known for his athletic jumps, which were the longest and highest in the history of figure skating. Hines reported that his Axel measured four feet high and 25 feet from takeoff to landing. Both men and women, including women skaters from Great Britain, were doubling Salchows and loops in their competition programs.[21]

During the post-war period, American skater Dick Button, who "intentionally tried to bring a greater athleticism to men's skating",[19] performed the first double Axel in competition in 1948 and the first triple jump, a triple loop, in 1952.[19] Triple jumps, especially triple Salchows, became more common for male skaters during the 1950s and early 1960s, and female skaters, especially in North America, included a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, men commonly performed triple Salchows and women regularly performed double Axels in competitions. Men would also include more difficult multi-revolution jumps like triple flips, Lutzes, and loops; women included triple Salchows and toe loops. In the 1980s men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples such as the loop jump.[22] By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.[23] According to Kestnbaum, jumps like the triple Lutz became more important during women's skating competitions.[24] The last time a woman won a gold medal at the Olympics without a triple jump was Dorothy Hamill at the 1976 Olympics.[25]

Progress in women's single skating in the 2010s is associated with the rapid increase in the technical complexity of programs. Alina Zagitova, representing Eteri Tutberidze's team from Russia, claimed victory at the 2018 Winter Olympics with a performance that approached the theoretical limit of a program without triple axels and quadruple jumps. Following this, the next generation of figure skaters, such as Rika Kihira from Japan and Alena Kostornaia (Tutberidze team), began setting records by incorporating the triple Axel into their programs. According to sports reporter Dvora Meyers, the "quad revolution in women's figure skating" began in 2018, when Kostornaia's teammate Alexandra Trusova began performing a quadruple Salchow when she was still competing as a junior.[25] She became the first female skater to successfully land a quadruple Lutz, a quadruple flip, and a quadruple toe loop.[26]

American skater Ilia Malinin is the first and only person to successfully land a fully rotated quadruple Axel in international competition, a jump widely regarded as the most difficult in figure skating.[27]

Types of jumps

[edit]- Anomalies in the takeoff and landing are highlighted in bold and italic.

- All basic figure skating jumps are landed backwards.

| Abbr. | Jump | Toe assist

|

Change of foot

|

Change of edge

|

Change of curve

|

Change of direction

|

Takeoff edge | Landing edge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Axel | — | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | Forward outside | Outside (opposite foot)

|

| Lz | Lutz | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | Backward outside | Outside (opposite foot)

|

| F | Flip | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward inside | Outside (opposite foot)

|

| Lo | Loop (Rittberger) | — | — | — | — | — | Backward outside | Outside (same foot)

|

| S | Salchow | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward inside | Outside (opposite foot)

|

| T | Toe loop | ✓ | — | — | — | — | Backward outside | Outside (same foot)

|

| Eu | Euler (half-loop)

|

— | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward outside | Inside (opposite foot)

|

The six most common jumps can be divided into two groups: toe jumps (the toe loop, the flip, and the Lutz) and edge jumps (the Salchow, the loop, and the Axel).[28] The Euler jump, which was known as a half-loop before 2018, is an edge jump.[29] The ISU classifies jumps in order of their difficulty: the toe loop, the Salchow, the loop, the flip, the Lutz, and the Axel; and by the number of revolutions.[30] All single jumps, except for the Axel, include one revolution, double jumps include two revolutions, and so on. More revolutions earn skaters more points.[14] Jumps with more revolutions have increased in importance "as a measure of technical and athletic ability, with attention paid to clean takeoffs and landings".[31] Pair skaters perform two types of jumps: side-by-side jumps, in which jumps are accomplished side by side and in unison, and throw jumps, in which the woman performs the jump when assisted and propelled by her partner.[14] Quintuple jumps are not allowed in the short program.[32][why?]

Toe jumps tend to be higher than edge jumps because skaters press the toe pick of their skate into the ice on takeoff.[14] Both feet are on the ice at the time of takeoff, and the toe-pick in the ice at takeoff acts as a pole vault. It is impossible to add a half-revolution to toe jumps.[33][why?] Skaters accomplish edge jumps by leaving the ice from any of their skates' four possible edges; lift is "achieved from the spring gained by straightening of a bent knee in combination with a swing of the free leg".[14] They require precise rotational control of the skater's upper body, arms, and free leg, and of how well they lean into the takeoff edge. The preparation going into the jump and its takeoff, as well as controlling the rotation of the preparation and takeoff, must be precisely timed.[34] When a skater executes an edge jump, they must extend their leg and use their arms more than when they execute toe jumps.[35]

Euler

[edit]The Euler is an edge jump. It was known as the half-loop jump in International Skating Union (ISU) regulations prior to the 2018–2019 season, when the name was changed.[29] In Europe, the Euler is also called the Thorén jump, after its inventor, Swedish figure skater Per Thorén.[36] The Euler is executed when a skater takes off from the back outside edge of one skate and lands on the opposite foot and edge. It is most commonly done prior to the third jump during a three-jump combination, and serves as a way to put a skater on the correct edge in order to attempt a Salchow jump or a flip jump. It can be accomplished only as a single jump.[why?] The Euler has a base point value of 0.50 points, when used in combination between two listed jumps, and also becomes a listed jump.[29][37]

Toe loop

[edit]The toe loop jump is the simplest jump in figure skating.[38] It was invented in the 1920s by American professional figure skater Bruce Mapes.[39] In competition, the base value of a single toe loop is 0.40; the base value of a double toe loop is 1.30; the base value of a triple toe loop is 4.20; the base value of a quadruple toe loop is 9.50; and the base value of the quintuple toe loop is 14.00.[40]

The toe loop is considered the simplest jump because not only do skaters use their toe-picks to execute it, but their hips are already facing the direction in which they will rotate.[41] The toe loop is the easiest jump to add multiple rotations to because the toe-assisted takeoff adds power to the jump and because a skater can turn their body towards the assisting foot at takeoff, which slightly reduces the rotation needed in the air.[42] It is often added to more difficult jumps during combinations, and is the most common second jump performed in combinations.[43] It is also the most commonly attempted jump,[41] as well as "the most commonly cheated on take off jump",[44][45] or a jump in which the first rotation starts on the ice rather than in the air.[42]

Flip

[edit]The ISU defines a flip jump as "a toe jump that takes off from a back inside edge and lands on the back outside edge of the opposite foot".[39] It is executed with assistance from the toe of the free foot.[46] In competition, the base value of a single flip is 0.50; the base value of a double flip is 1.80; the base value of a triple flip is 5.30; the base value of a quadruple flip is 11.00; and the base value of a quintuple flip is 14.00.[40]

Lutz

[edit]The ISU defines the Lutz jump as "a toe-pick assisted jump with an entrance from a back outside edge and landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot".[39] It is the second-most difficult jump in figure skating[38] and "probably the second-most famous jump after the Axel".[43] It is named after figure skater Alois Lutz from Vienna, Austria, who first performed it in 1913.[39][43] In competition, the base value of a single Lutz is 0.60; the base value of a double Lutz is 2.10; the base value of a triple Lutz is 5.90; the base value of a quadruple Lutz is 11.50; and the value of a quintuple Lutz is 14.00.[40] A "cheated" Lutz jump without an outside edge is commonly called a "flutz".[43]

Salchow

[edit]The Salchow jump is an edge jump. It was named after its inventor, Ulrich Salchow, in 1909. The Salchow is accomplished with a takeoff from the back inside edge of one foot and a landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot.[39][47] It is "usually the first jump that skaters learn to double, and the first or second to triple".[48] Timing is critical when performing the Salchow because both the takeoff and the landing must be on the backward edge.[43] A Salchow is deemed cheated if the skate blade starts to turn forward before the takeoff, or if it has not turned completely backward when the skater lands back on the ice.[48]

In competition, the base value of a single Salchow is 0.40; the base value of a double Salchow is 1.30; the base value of a triple Salchow is 4.30; the base value of a quadruple Salchow is 9.70; and the value of a quintuple Salchow is 14.00.[40]

Loop

[edit]The loop jump is an edge jump. It was believed to be created by German figure skater Werner Rittberger, and is known as the Rittberger in Russian and German.[49] It also gets its name from the shape the blade would leave on the ice if the skater performed the rotation without leaving the ice.[50] According to U.S. Figure Skating, the loop jump is "the most fundamental of all the jumps".[43] The skater executes it by taking off from the back outside edge of the skating foot, turning one rotation in the air, and landing on the back outside edge of the same foot.[46] It is often performed as the second jump in a combination.[51]

In competition, the base value of the single loop jump is 0.50; the base value of a double loop is 1.70; the base value of a triple loop is 4.90; the base value of a quadruple loop is 10.50; and the value of a quintuple loop jump.[40]

Axel

[edit]The Axel jump, also called the Axel Paulsen jump for its creator, Norwegian figure skater Axel Paulsen, is an edge jump.[52] It is figure skating's oldest and most difficult jump.[18][50] The Axel jump is the most studied jump in figure skating.[53] It is the only jump that begins with a forward takeoff, which makes it the easiest jump to identify.[28] A double or triple Axel is required in the short program for both senior and junior men, and for senior women. An Axel-type jump is required in the free skating program for all levels of single skating.[54] Junior pair skaters have the choice of performing either a double Axel or double loop in the short programs. Pair skaters can also choose, in their free skating program, a double Axel for one of their jumps in the jump combination or jump sequence.[55]

The Axel has an extra half-rotation, which, as figure skating expert Hannah Robbins says, makes a triple Axel "more a quadruple jump than a triple".[56] Sports reporter Nora Princiotti says, about the triple Axel, "It takes incredible strength and body control for a skater to get enough height and to get into the jump fast enough to complete all the rotations before landing with a strong enough base to absorb the force generated".[57] According to American skater Mirai Nagasu, "Falling on the triple Axel is really brutal."[58]

In competition, the base value of a single Axel is 1.10; the base value of a double Axel is 3.30; the base value of a triple Axel is 8.00; the base value of a quadruple Axel is 12.50; and the base value of a quintuple Axel is 14.00.[40] According to The New York Times, the triple Axel has become more common for male skaters to perform;[59] as of 2025, Ilia Malinin from the U.S. is the only skater to successfully complete a quadruple Axel.[60]

Rules and regulations

[edit]The ISU defines a jump element for both single skating and pair skating disciplines as "an individual jump, a jump combination or a jump sequence".[5] Jumps are not allowed in ice dance.[61]

Also according to the ISU, jumps must have the following characteristics to earn the most points: they must have "very good height and very good length";[3] they must be executed effortlessly, including the rhythm demonstrated during jump combinations; and they must have good takeoffs and landings. The following are not required, but also taken into consideration: there must be steps executed before the beginning of the jump, or it must have either a creative or unexpected entry; the jump must match the music; and the skater must have, from the jump's takeoff to its landing, a "very good body position".[3]

A jump combination consists of "two jumps performed in an immediate and consecutive order".[62] In a jump combination, the landing foot of the first jump must be the take-off foot of the second jump. The skater can also execute one full revolution on the ice between the jumps, meaning that their free foot can touch the ice with no weight transfer. An Euler jump can be included in a jump combination, although not during the short program, and only once during the free skating program.[5]

A jump sequence consists of "two or three jumps in Single Skating or two jumps in Pair Skating of any number of revolutions in which the second and/or the third jump is an Axel type jump with a direct step from the landing curve of the first/second jump into the take-off curve of the Axel jump".[63] The free foot can touch the ice, but there must be no weight transfer on it, and if the skater makes one full revolution between the jumps, the element continues to be deemed a jump sequence and receives its full value.[63] Prior to the 2022-23 season, the skater received only 80% of the base value of the jumps executed in a jump sequence.[64]

All jumps are considered in the order they are completed. If an extra jump or jumps are executed, the extra jump(s) not in accordance with requirements will have no value.[65] The limitation on the number of jumps skaters can perform in their programs, called the "Zayak Rule" after American skater Elaine Zayak, has been in effect since 1983, after Zayak performed six triple jumps, four toe loop jumps, and two Salchows in her free skating program at the 1982 World Championships.[66][23] Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum says the ISU established the rule "in order to encourage variety and balance rather than allowing a skater to rack up credit for demonstrating the same skill over and over".[23] Kestnbaum also says that as rotations in jumps for both men and women have increased skaters have increased the difficulty of jumps by adding more difficult combinations and by adding difficult steps immediately before or after their jumps, resulting in "integrating the jumps more seamlessly into the flow of the program".[67]

Single skating

[edit]Skaters earn extra points for executing jumps in the second half of their programs. In their short programs, they receive a bonus on their final jumping pass executed in the second half of the program. In their free skating programs, the bonus applies to the final three jumping passes, also if they execute the jumps during the second half of the program. This limitation has been called the "Zagitova Rule", named for Alina Zagitova from Russia, who won the gold medal at the 2018 Winter Olympics by "backloading" her free skating program, or placing all her jumps in the second half of the program in order to take advantage of the rule in place at the time that awarded a ten percent bonus to jumps performed during the second half of the program.[68] Also starting in 2018, single skaters could repeat the same two triple or quadruple jumps only in their free skating programs. They could repeat four-revolution jumps only once, and the base value of the triple Axel and quadruple jumps were "reduced dramatically".[64] As of 2022, jump sequences consisted of two or three jumps, but the second or third jump had to be an Axel. Jump sequences began to be counted for their full value and skaters could include single jumps in their step sequences as choreographic elements without incurring a penalty.[69]

Junior men and women single skaters are not allowed to perform quadruple jumps in their short programs.[70] In their short programs, both junior and senior skaters have to perform either a double or triple Axel jump, one triple or quadruple jump, and a jump combination.[71] In their free-skating programs, both junior and senior skaters have to complete seven jump elements, one of which has to be an Axel-type jump.[72]

Pair skating

[edit]

Pair teams, both juniors and seniors, must perform one solo jump during their short programs; it can include a double loop or double Axel for juniors, or any kind of double or triple jump for seniors.[73] In the free skating program, for both juniors and seniors, skaters are limited to a maximum of one jump combination or sequence.[74] A jump sequence consists of two or three jumps of any number of revolutions, in which the second and/or the third jump is an Axel type jump. Jumps during the short program that do not satisfy the requirements (including the wrong number of revolutions) will have no value.[55] In the free skating program, when the partners perform an unequal number of revolutions as a solo jump, or as part of a jump combination or jump sequence, the jump with the smaller number of revolutions is counted. When they "definitely perform" different types of jumps, they receive no credit.[75] In the free skating program, repeated jumps executed with over two revolutions "of the same name and number of revolutions" are not counted, although the two jumps may be the same within the same jump combination or jump sequence. The ISU also states, "Jumps are considered in the order of their combination".[75]

Throw jumps are "partner-assisted jumps in which the Woman is thrown into the air by the Man on the takeoff and lands without assistance from her partner on a backward outside edge".[76][77] Skate Canada says, "The male partner assists the female into flight."[46] The types of throw jumps include: the throw Axel, the throw Salchow, the throw toe loop, the throw loop, the throw flip, and the throw Lutz.[46] The throw triple Axel is a difficult throw to accomplish because the woman must perform three-and-one-half revolutions after being thrown by the man, a half-revolution more than other triple jumps, and because it requires a forward takeoff.[78] The speed of the team's entry into the throw jump and the number of rotations performed increases its difficulty, as well as the height and/or distance they create.[46] Pair teams must perform one throw jump during their short programs; senior teams can perform any double or triple throw jump, and junior teams must perform a double or triple toe loop, or a double or triple flip or Lutz. If a throw jump in the short program is not done correctly, including if it has the wrong number of revolutions, it receives no value. Both juniors and seniors must complete a maximum of two different throw jumps in their free skating programs.[77]

Execution

[edit]According to Kestbaum, jumps are divided into eight parts: the set-up, load, transition, pivot, takeoff, flight, landing, and exit. All jumps, except for the Axel, are taken off while skating backward; Axels are entered into by skating forward.[79] Skaters travel in three directions simultaneously while executing a jump: vertically (up off the ice and back down); horizontally (continuing along the direction of travel before leaving the ice); and around.[31][80] They travel in an up and across, arc-like path while executing a jump, much like the projectile motion of a pole-vaulter. A jump's height is determined by vertical velocity and its length is determined by vertical and horizontal velocity.[81] The trajectory of the jump is established during takeoff, so the shape of the arc cannot be changed once a skater is in the air.[82] Their body absorbs up to 13–14 g-forces each time they land from a jump,[6] which sports researchers Lee Cabell and Erica Bateman say contributes to overuse injuries and stress fractures.[83]

Skaters add variations or unusual entries and exits to jumps to increase difficulty. For example, they will perform a jump with one or both arms overhead or extended at the hips, demonstrating their ability to generate rotation from the takeoff edge and their entire body, rather than relying solely on their arms. It also demonstrates their back strength and technical ability to complete the rotation without relying on their arms. Unusual entries into jumps demonstrate that skaters are able to control both the jump and, with little preparation, the transition from the previous move to the jump.[79] Skaters rotate more quickly when their arms are pulled in tightly to their bodies, which requires strength to keep their arms from being pulled away from their bodies as they rotate.[84]

According to Deborah King and her colleagues from Ithaca College, there are basic physics common to all jumps, regardless of the skating techniques required to execute them.[35] Factors such as angular momentum, the moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and the skater's center of mass determine if a jump is successfully completed.[85][86] Unlike jumping from dry land, which is fundamentally a linear movement, jumping on the ice is more complicated because of angular momentum. For example, most jumps involve rotation.[87] Scientist James Richards from the University of Delaware says successful jumps depend upon "how much angular momentum do you leave the ice with, how small can you make your moment of inertia in the air, and how much time you can spend in the air".[85] Richards found that a skater tends to spend the same amount of time in the air when performing triple and quadruple jumps, but their angular momentum at the start of triples and quadruples is slightly higher than it is for double jumps. The key to completing higher-rotation jumps is controlling the moment of inertia. Richards also found that many skaters, although they were able to gain the necessary angular momentum for takeoff, had difficulty gaining enough rotational speed to complete the jump.[85] King and her colleagues agree that skaters must be in the air long enough, have enough jump height to complete the required revolutions, and gain enough vertical velocity as they jump off the ice. However, different jumps require different patterns of movement. Skaters performing quadruple jumps tend to be in the air longer and have more rotational speed. King also found that most skaters "actually tended to skate slower into their quads as compared to their triples",[88] although the differences in the speed at which they approached triples and quadruples were small. King conjectured that slowing their approach into the jumps was due to skaters' "confidence and a feeling of control and timing for the jump",[88] rather than any difference in how they executed them. Vertical takeoff velocity, however, was higher for both quadruple and triple toe loops, resulting in "higher jumps and more time in the air to complete the extra revolution for the quadruple toe-loop".[88] As Tanya Lewis of Scientific American puts it, executing quadruple jumps, which as of 2022, has become more common in both male and female single skating competitions, requires "exquisite strength, speed and grace".[35]

For example, a skater could successfully complete a jump by making small changes to their arm position partway through the rotation, and a small bend in the hips and knees allows a skater "to land with a lower center of mass than they started with, perhaps seeking out a few precious degrees of rotation and a better body position for landing".[85] When they execute a toe jump, they must use their skate's toe pick to complete a pole-vaulting-type motion off the ice, which along with extra horizontal speed, helps them store more energy in their leg. As they rotate over their leg, their horizontal motion converts into tangential velocity.[35] King, who believes quintuple jumps are mathematically possible, says that in order to execute more rotations, they could improve their rotational momentum as they execute their footwork or approach into their takeoff, creating torque about the rotating axis as they come off the ice. She also says that if skaters can increase their rotational momentum while "still exploding upward"[35] they can rotate faster and increase the number of revolutions they perform. Sports writer Dvora Meyers, reporting on Russian coaching techniques, says female skaters executing more quadruple jumps in competition use what experts call pre-rotation, or the practice of twisting their upper bodies before they take off from the ice, which allows them to complete four revolutions before landing. Meyers also says the technique depends on the skater's being small, light, and young, and that it puts more strain on the back because they do not use as much leg strength. As a skater ages and goes through puberty, however, they tend not to be able to execute quadruple jumps because "the technique wasn't sound to start with".[25] They also tend to retire before the age of 18 due to the increase in back injuries.[25]

Since the tendency of an edge is toward the center of the circle created by that edge, a skater's upper body, arms, and free leg also have a tendency to be pulled along by the force of the edge. If the upper body, arms, and free leg are allowed to follow passively, they will eventually overtake the edge's rotational edge and will rotate faster, a principle that is also used to create faster spins. The inherent force of the edge and the force generated by a skater's upper body, arms, and free leg tend to increase rotation, so successful jumping requires precise control of these forces. Leaning into the curvature of the edge is how skaters regulate the edge's inherent angular momentum. Their upper body, arms, and free leg are controlled by what happens at the time of preparation for the jump and its takeoff, which are designed to produce the correct amount of rotation on the takeoff. If they do not have enough rotation, they will not be at the correct position at the takeoff; if they rotate too much, their upper body will not be high enough in the air. Skaters must keep track of the many different movements and body positions, as well as the timing of those movements relative to each other and to the jump itself, which requires hours of practice but once mastered, becomes natural.[89]

The number of possible combinations jumps is limitless; if a turn or change of feet is permitted between combination jumps, any number of sequences is possible, although if the landing of one jump is the takeoff of the next, as is the case in loop combinations, how the skater lands will dictate the possibilities going into subsequent jumps. Rotational momentum tends to increase during combination jumps, so skaters should control rotation at the landing of each jump; if a skater does not control rotation, they will over-rotate on subsequent jumps and probably fall. The way skaters control rotation differs depending on the nature of the landing and takeoff edges, and the way they use their arms, which regulate their shoulders and upper body position, and their free leg, which dictates the positioning of their hips. If the landing on one jump leads directly into the takeoff of the jump that follows it, the bend on the landing leg of the first jump serves as preparation for the spring of the takeoff of the subsequent jump. If some time elapses between the completion of the first jump and the takeoff of the subsequent one, or if a series of movements serves as preparation for the subsequent jump, the leg bend for the spring can be separated from the bend of the landing leg.[90]

History of first jumps

[edit]The following table lists first recorded jumps in competition for which there is secure information.

| Jump | Abbr. | Men | Year | Women | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single toe loop | 1T | 1920s | n/a | [39] | ||

| Single Salchow | 1S | 1909 | 1917 | [91][17][39] | ||

| Single loop | 1Lo | 1910 | n/a | [39][92] | ||

| Single Lutz | 1Lz | 1913 | n/a | [39] | ||

| Single Axel | 1A | 1882 | 1920s | [93] | ||

| Double Salchow | 2S | n/a | 1920s | 1930s | [94] | |

| Double Lutz | 2Lz | n/a | 1949 | [95][96] | ||

| Double Axel | 2A | 1948 | 1953 | [39][97] | ||

| Triple toe loop | 3T | 1964 | n/a | [98] | ||

| Triple Salchow | 3S | 1955 | 1962 | [98] | ||

| Triple loop | 3Lo | 1952 | 1968 | [99] | ||

| Triple flip | 3F | n/a | 1981 | [39] | ||

| Triple Lutz | 3Lz | 1962 | 1978 | [98] | ||

| Triple Axel | 3A | 1978 | 1988 | [39] | ||

| Quadruple toe loop | 4T | 1988 | 2018 | [98][100] | ||

| Quadruple Salchow | 4S | 1998 | 2002 | [98] | ||

| Quadruple loop | 4Lo | 2016 | 2022 | [98] | ||

| Quadruple flip | 4F | 2016 | 2019 | [98][101] | ||

| Quadruple Lutz | 4Lz | 2011 | 2018 | [41][98] | ||

| Quadruple Axel | 4A | 2022 | none ratified | [102] | ||

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Women were referred to as ladies in ISU regulations and communications until the 2021–22 season.[1]

- ^ Outside of competition

- ^ According to https://olympics.com/en/athletes/jacqueline-du-bief, Jacqueline du Bief, in 1952, was the first woman to do a double Lutz in international competition, but it was a controversial win, and that she later wrote in her book Thin Ice, that American Sonya Klopfer deserved the title.

- ^ According to the 2025–26 ISU Media Guide, Petra Burka can be credited as the first woman to do a triple Salchow, but a report from the 1961 European Championships noted that Helli Sengstschmid (AUT) and Jana Mrazkova (CZE) landed a triple Salchow then.

- ^ Domestic competition.

References

[edit]- ^ "Results of Proposals in replacement of the 58th Ordinary ISU Congress 2021" (Press release). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b c Hines 2011, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d "Communication No. 2558: Single & Pair Skating Levels of Difficulty and Guidelines for Marking Grade of Execution and Program Components". International Skating Union. Lausanne, Switzerland. 26 April 2023. p. 7. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 289.

- ^ a b c S&P/ID 2024, p. 103

- ^ a b Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 35.

- ^ a b Hines 2006, p. 101.

- ^ Hines 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 131–132.

- ^ a b c Kestnbaum 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 68.

- ^ Kestnbaum 2003, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d e Hines 2011, p. 132.

- ^ Hines 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Hines 2006, p. 5.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 92.

- ^ a b Hines 2011, p. xxxii.

- ^ a b c Kestnbaum 2003, p. 93.

- ^ Hines 2006, p. 102.

- ^ Hines 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Kestnbaum 2003, pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b c Kestnbaum 2003, p. 96.

- ^ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Meyers, Dvora (3 February 2022). "How Quad Jumps Have Changed Women's Figure Skating". FiveThirtyEight. ABC News. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Alexandra Trusova leads quad revolution in debut senior season". The Japan Times. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ Carpenter, Les (14 September 2022). "U.S. figure skater Ilia Malinin lands first quad axel in competition". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b Abad-Santos, Alexander (5 February 2014). "A GIF Guide to Figure Skaters' Jumps at the Olympics". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b c Cornetta, Katherine (1 October 2018). "Breaking Down an Euler". Fanzone.com. U.S. Figure Skating. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2024" (PDF). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. p. 83. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 282.

- ^ ISU No. 2707, p. 12

- ^ Petkevich 1988, p. 237.

- ^ Petkevich 1988, p. 199.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, Tanya (14 February 2022). "How Olympic Figure Skaters Break Records with Physics". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 222.

- ^ ISU No. 2707, p. 2

- ^ a b Park, Alice (8 February 2018). "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Figure Skating Jumps and Scores". Time. Archived from the original on 13 May 2025. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Media Guide, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f ISU No. 2707, pp. 2—4

- ^ a b c Sarkar, Pritha; Fallon, Clare (28 March 2017). "Figure Skating – Breakdown of Quadruple Lumps, Highest Scores and Judging". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 287.

- ^ a b c d e f USFS, p. 2

- ^ Tech panel (Single skating), p. 24

- ^ Tech panel (Pair skating), p. 18

- ^ a b c d e "Skating Glossary". Skate Canada. 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 193.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 284.

- ^ Hines 2011, p. 150.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 285.

- ^ Kestnbaum, p. 285

- ^ USFS, p. 1

- ^ Mazurkiewicz, Anna; Twańsak, Dagmara; Urbanik, Czesław (July 2018). "Biomechanics of the Axel Paulsen Figure Skating Jump". Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism. 25 (2): 3. doi:10.2478/pjst-2018-0007.

- ^ Tech panel (Single skating), p. 21

- ^ a b Tech panel (Pair skating), p. 17

- ^ Robbins, Hannah (11 February 2018). "Triple Axel New Ladies' Figure Skating Staple". The Collegian. Tulsa, Oklahoma: University of Tulsa. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Princiotti, Nora (12 February 2018). "What is a Triple Axel? And Why is it So Hard for Figure Skaters to Pull Off?". Boston.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Calfas, Jennifer (12 February 2018). "Why Mirai Nagasu's Historic Triple Axel at the Olympics Is Such a Big Deal". Time. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Victor, Daniel (12 February 2018). "Mirai Nagasu Lands Triple Axel, a First by an American Woman at an Olympics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Schad, Tom (29 March 2025). "What is a Quad Axel? Explaining Ilia Malinin's Famed Figure Skating Jump". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2 April 2025. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Samuels, Robert (18 February 2018). "Ice Dancing is More than Pairs Figure Skating Without Jumps". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Figure Skating 101: Glossary". NBC Olympics. 26 June 2025. Archived from the original on 2 July 2025. Retrieved 7 July 2025.

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2024, p. 104

- ^ a b "New Season New Rules – International Figure Skating". International Figure Skating. 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ S&P/ID 2024, p. 113

- ^ Hines 2006, p. xxvii.

- ^ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Germano, Sara (21 February 2018). "In Figure Skating, Russia's (Perfectly Legal) Secret Sauce". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "New Rules for new Development in Figure Skating". International Skating Union. 14 October 2022. Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Russell, Susan D. (December 2019). "Talent and Tenacity: Next Gen Makes History on the Junior Grand Prix Circuit". International Figure Skating. p. 23.

- ^ S&P/ID 2024, pp. 106—108

- ^ S&P/ID 2025, pp. 110—111

- ^ Media Guide, p. 14

- ^ S&P/ID, p. 122

- ^ a b Tech panel, Pair skating, p. 19

- ^ S&P/ID 2024, p. 117

- ^ a b Tech Panel, Pair skating, p. 21

- ^ Henderson, John (26 January 2006). "Duo Throws Caution to Wind". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 19.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 20.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 38.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Lamb, Evelyn (7 February 2018). "How Physics Keeps Figure Skaters Gracefully Aloft". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Cabell & Bateman 2018, p. 27.

- ^ Petkevich 1988, p. 193.

- ^ a b c King et al. 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Petkevich 1988, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Petkevich 1988, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Stevens 2023, p. 21-22.

- ^ Stevens 2023, p. 51.

- ^ Media guide, pp. 19—20

- ^ Hines 2011, p. xxiv.

- ^ Elliott, Helene (13 March 2009). "Brian Orser Heads List of World Figure Skating Hall of Fame inductees". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Stevens 2023, p. 83.

- ^ Judd, Ron C. (2001). The Winter Olympics: An Insider's Guide to the Legends, the Lore, and the Games. Seattle, Wash.: The Mountaineer Books. p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Media guide, p. 21

- ^ Pucin, Diane (7 January 2002). "Button Has Never Been Known to Zip His Lip". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ "A Quadruple Jump on Ice". The New York Times. Associated Press. 26 March 1988. p. 57. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Griffiths, Rachel; Jiwani, Rory (6 December 2019). "As it Happened: Wins for Kostornaia and Chen on Last Day of Competition in Turin". Olympic Channel. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ "Ilia Malinin (USA) lands first quad Axel – International Skating Union". International Skating Union. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

Works cited

[edit]- Cabell, Lee; Bateman, Erica (2018). "Biomechanics in Figure Skating". In Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (eds.). The Science of Figure Skating. New York: Routledge. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0.

- "Communication No. 2707: Single & Pair Skating Scale of Values (ISU No. 2707)" (PDF). International Skating Union. 16 May 2025. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2025. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07286-4.

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81087-0857.

- "Identifying Jumps (USFS)" (PDF). U.S. Figure Skating. 12 July 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

- "ISU Figure Skating Media Guide 2025/26 (Media Guide)" (PDF). International Skating Union. Lausanne, Switzerland. 21 August 2025. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2025. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- "ISU Technical Panel Handbook Pair Skating 2025-2026" (Tech panel, Pair skating). 25 July 2025. p. 18. Archived from the original on 12 August 2025. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- "ISU Technical Panel Handbook Single Skating 2025-2026" (Tech panel, Single skating). International Skating Union. 25 July 2025. p. 24. Archived from the original on 12 August 2025. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- King, Deborah; Smith, Sarah; Higginson, Brian; Muncasy, Barry; Scheirman, Gary (2004). "Characteristics of Triple and Quadruple Toe-Loops Performed during The Salt Lake City 2002 Winter Olympics". Sports Biomechanics. 3 (1): 109–123. doi:10.1080/14763140408522833.

- Petkevich, John Misha (1988). Sports Illustrated Figure Skating: Championship Techniques (1st ed.). New York: Sports Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-4616-6440-6. OCLC 815289537.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2024"(S&P/ID 2024). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- Stevens, Ryan (2023). Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Independently published. ISBN 979-8374044348.

Figure skating jumps

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Classification

In figure skating, a jump is a technical element in which a skater propels themselves into the air from an edge on one foot, completes one or more mid-air rotations, and lands on the edge of one foot—most from a backward position, though connecting jumps like the Euler land forward.[5] This airborne phase distinguishes jumps from other skating movements like steps or turns, requiring precise control of body position, speed, and timing to achieve height and rotation.[1] Jumps are primarily classified into two categories based on the takeoff mechanism: edge jumps and toe-assisted jumps. Edge jumps rely solely on the skating foot's blade edge—either inside or outside—for propulsion, without assistance from the toe pick, as seen in jumps like the loop, Salchow, and Axel.[1] In contrast, toe-assisted jumps incorporate the toe pick of the non-skating foot to aid takeoff from a backward edge, exemplified by the toe loop, flip, and Lutz.[5] Jumps are further distinguished by the number of rotations completed in the air, ranging from single (one full revolution, or 1.5 for the Axel due to its forward takeoff) to double, triple, and quadruple revolutions, with higher rotations increasing difficulty and base value.[5] The Euler jump, an unlisted edge jump taken off from a back outside edge and landed on the forward inside edge of the opposite foot, serves as a connecting element in combinations or sequences without contributing to the total rotation count of listed jumps.[6] In free skating programs, jumps form high-value elements that significantly contribute to the technical element score (TES), with their base values determined by type and rotations, further modified by execution quality to reward technical prowess and risk.[5]Basic Mechanics

Figure skating jumps are governed by core biomechanical principles that enable skaters to generate height, rotation, and control in the air. The conservation of angular momentum is fundamental, allowing a skater to increase rotational velocity by reducing their moment of inertia—typically by pulling the arms and free leg close to the body during flight—without external torques acting on the system.[7] This principle ensures that the total angular momentum acquired at takeoff remains constant, facilitating multiple revolutions in jumps like triples or quads. Complementing this, centrifugal force provides an outward pull during rotation, which helps maintain a tight, stable body position against the inward collapse from rotational dynamics, particularly critical for higher-rotation jumps where forces can exceed several times body weight. Energy transfer at takeoff converts the skater's horizontal kinetic energy into vertical lift and rotational momentum through an explosive impulse against the ice, primarily via the pushing leg's extension and the blade's edge engagement.[8] Optimal transfer requires coordinated hip, knee, and ankle extension in a stretch-shortening cycle, maximizing ground reaction forces—exceeding twice body weight—to propel the skater upward, with flight times typically ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 seconds for triple jumps. Essential body positions support these dynamics: the free leg is extended backward and slightly upward to enhance lift and initiate rotation, arms are drawn inward across the chest to accelerate spin via angular momentum conservation, and core muscles are engaged to counteract torsional forces and preserve axial alignment. Several factors influence jump height and rotational speed. Entry speed into the jump directly scales available kinetic energy, with faster approaches (around 5.5-6.5 m/s for advanced jumps) yielding greater vertical velocity (around 3.0-3.3 m/s)—and thus higher air time, though excess speed can compromise rotation control if not balanced.[10] The blade's rocker, its longitudinal curvature (typically 7-8 feet or 2.1-2.4 meters radius), enables the necessary inside or outside edge during the entry curve, influencing takeoff angle and impulse direction by allowing the skater to rock onto the appropriate portion of the blade.[11] Ice conditions, including temperature and texture, affect friction and energy dissipation, with softer ice providing better grip for edge work but potentially reducing rebound efficiency. Preparatory elements build the necessary momentum and positioning for effective jumps. Backward crossovers accelerate the skater while establishing the rotational axis, generating forward lean and edge pressure essential for the entry curve.[12] Three-turns, conversely, initiate a tighter curve by reversing the skate direction on one foot, aiding precise alignment for edge takeoffs in jumps like the loop or Salchow, and conserving energy through minimal speed loss.[13]Types of Jumps

Axel

The Axel jump is the only jump in figure skating that takes off from a forward-facing position, specifically from the forward outside edge of the skater's takeoff foot—typically the left foot for right-handed skaters and the right foot for left-handed skaters. This forward entry distinguishes it from all other jumps, which begin from a backward approach, and necessitates an additional half-rotation in the air to compensate for the initial forward momentum, resulting in 1.5 revolutions for a single Axel. The landing occurs on the backward outside edge of the opposite foot after completing the required rotations.[14][15] Execution of the Axel begins with a deep knee bend on the takeoff leg to generate upward propulsion, while the free leg is swung forcefully forward and across the body to build speed and initiate the jump's height and distance. The arms are positioned close to the body initially, then pulled tightly across the chest to facilitate counterclockwise rotation for most skaters, maintaining a compact air position to achieve the necessary revolutions. This technique demands precise timing and explosive power from the lower body to convert the forward speed into rotational energy.[14] The Axel's forward takeoff contributes to its reputation as the most challenging single jump in figure skating, as it generates greater entry speed compared to backward takeoffs, increasing the risk of under-rotation—where the skater fails to complete the full revolutions—particularly in multi-revolution variations. The extra half-rotation amplifies demands on balance and aerial control, making it historically significant as the most complex jump to master at the single level.[16][15] Variations of the Axel scale in difficulty with additional revolutions: the double Axel requires 2.5 rotations, the triple 3.5, and the quadruple 4.5, with the latter demanding exceptional vertical height (often exceeding 0.8 meters) and takeoff speeds around 7 m/s to achieve sufficient air time. The quadruple Axel stands out as the last jump type to be successfully landed at the competitive level, highlighting its extreme technical barriers.[14][16]Lutz

The Lutz is a toe-assisted jump in figure skating, executed with a takeoff from a backward outside edge of the gliding foot and landing on the backward outside edge of the opposite foot. For skaters rotating counterclockwise— the standard direction for most competitors—the skater glides backward on the outside edge of the left skate, extends the right leg behind to tap the ice with the toe pick of the right skate for propulsion, and initiates rotation while pushing off the left edge. This distinguishes it as one of the high-value jumps due to its edge and rotational demands. The technique begins with a long, curving entry on the backward outside edge to generate speed and momentum, often tracing a wide arc near the rink's barrier to maximize the glide. As the skater approaches takeoff, the hips and shoulders counter-rotate against the direction of travel—typically clockwise on the entry curve—to prepare for the counterclockwise rotation in the air, a maneuver that can lead to pre-rotation if overdone. At the moment of pick, the free leg (right for counterclockwise rotators) swings forward and across, aiding the lift, while the arms pull in to initiate the turn; studies of elite skaters show an average pre-rotation of about 96 degrees at takeoff, emphasizing the need for precise timing to conserve angular momentum. This pronounced counter-rotation sets the Lutz apart from simpler toe jumps like the toe loop, which uses a forward inside edge without such extensive curving preparation.[17][1] Maintaining the purity of the outside edge throughout the entry and takeoff presents significant challenges, as any deviation toward the inside edge—known as "flutzing"—compromises the jump's integrity and risks detection by judges. The wide entry arc further amplifies difficulty by requiring sustained edge control under speed, and the jump's structure facilitates combinations, as the free foot placement post-takeoff positions the skater well for a subsequent jump like a toe loop.[1][17] Variations of the Lutz include single, double, triple, and quadruple revolutions, with higher multiples demanding even greater speed on the entry curve and tighter air position to achieve full rotation. The quadruple Lutz, first landed in competition by Alexandra Trusova in 2018, exemplifies its status as one of the most demanding elements, prized for both base value and execution potential in elite programs. Unlike the flip, which shares the toe assist but takes off from a backward inside edge, the Lutz's outside edge requirement heightens its technical risk and reward.[1]Flip

The flip jump is a toe-assisted jump in figure skating, executed with a backward takeoff from the inside edge of the skater's left foot (for counterclockwise rotation) using the toe pick of the right foot to initiate lift, followed by rotation in the air and landing on the backward outside edge of the right foot. This jump belongs to the group of toe jumps, distinguished by its reliance on the pick for propulsion while emphasizing edge pressure from the skating foot. The International Skating Union recognizes the flip as a standard listed jump, with its identification hinging on the correct inside edge takeoff.[18] In technique, the flip features a shorter entry curve than the related Lutz jump, often involving a more compact backward glide before the pick and takeoff, which accentuates the need for precise blade control to maintain the inside edge and avoid shifting to an outside edge—a common error known as an "e" call for wrong edge. Skaters must actively pressure the inside hollow of the blade while drawing the free leg in, ensuring the body aligns for efficient rotation without leaning that could cause instability. This inside-edge demand contrasts with the Lutz's outside edge, making the flip's execution reliant on subtle weight distribution to prevent the blade from "flipping" outward during the pivot.[18] Challenges in performing the flip include edge confusion, where insufficient control leads to an unclear or incorrect edge, resulting in judge notations like "!" for questionable edges (affecting Grade of Execution) or "e" for definite errors (reducing base value by 20-30%), often culminating in falls or downgrades. Additionally, the flip's landing on the opposite foot's outside edge creates constraints for immediate transitions in combinations, as the positioning limits seamless connections to certain subsequent jumps compared to more versatile landings, contributing to its relative rarity in multi-jump sequences at competitive levels.[18] Variations of the flip include single, double, triple, and quadruple rotations, with each level increasing the required air time and rotational speed while maintaining the same takeoff and landing edges. The double and triple flips are standard in elite programs, valued equivalently to their Lutz counterparts in the Scale of Values (e.g., triple flip at 5.3 base points), but the quadruple flip remains exceptionally rare, successfully executed in competition by only a few athletes such as Alexandra Trusova due to the amplified demands on edge precision and power generation.[18][19]Loop

The loop jump is an edge jump in figure skating, executed without toe pick assistance, where the skater takes off from the back outside edge of one foot and lands on the back outside edge of the same foot, completing full rotations in the air. For skaters rotating counterclockwise—the majority in competitive figure skating—this involves the right foot for both takeoff and landing, with the free leg positioned behind during the approach to maintain balance and initiate the curve. The jump's purity relies entirely on the skating edge for propulsion and rotation, distinguishing it as one of the foundational edge jumps.[20][1] The technique begins with a tight, curved entry on the back outside edge, often approached via backward crossovers to build speed and depth while keeping the body aligned over the skating foot. At takeoff, the skater bends the knee deeply, presses firmly into the edge to generate upward lift, and initiates rotation from the hips and core without trunk lean or arm pull, ensuring a quick check to prevent over-rotation on the ice. In the air, the skater draws the free leg close to the axis for tight revolutions, relying on centrifugal force to hold the position. This edge-only method demands exceptional control to avoid scrunching or flattening the blade, which can reduce height and distance.[21][22] One of the primary challenges in the loop jump is maintaining a deep, consistent back outside edge through the entry and takeoff, as any shallowing can lead to insufficient torque and under-rotation. The same-foot landing further complicates execution, requiring precise weight placement to absorb impact without changing edges or stumbling forward, which is especially demanding at higher rotations. Unlike the Salchow, which uses a back inside edge takeoff and lands on the opposite foot's outside edge for easier momentum transfer, or the toe loop, which benefits from toe pick assistance for quicker setup, the loop's reliance on pure edging makes it notoriously difficult for combinations, as the landing position hinders immediate setup for subsequent jumps. It is regarded as one of the hardest pure edge jumps due to these factors, particularly in multi-revolution forms.[21][1] The loop jump is performed in single, double, triple, and quadruple variations, with each additional rotation increasing the demand for speed, power, and aerial tightness. The double loop adds one full revolution beyond the single, while the triple and quadruple require explosive hip drive and minimal air time loss, making the quadruple loop among the most technically advanced elements in the sport, successfully executed by elite skaters like Ilia Malinin.[21]Salchow

The Salchow jump is an edge jump in figure skating executed with a takeoff from the back inside edge of one foot and a landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot after one or more mid-air rotations. For skaters who rotate counterclockwise—the majority in competitive skating—the takeoff occurs from the left foot's back inside edge, while the landing is on the right foot's back outside edge. This distinguishes it as a pure edge jump, relying solely on the blade's edge for propulsion without toe pick assistance.[23] The technique begins with a backward entry, often via a three-turn or crossovers, where the skater swings the free leg (right for counterclockwise rotators) from behind the body forward and across, forming a "D" shape to build momentum. At takeoff, the free leg reaches approximately 90 degrees to the body axis before being drawn close to the skating leg, while the skater deeply bends the knee, applies pressure to the inside edge, and vaults upward to initiate rotation. This swing and edge pressure generate the necessary rotational torque and height, emphasizing timing to avoid prerotation or loss of edge control.[23][13] Executing the Salchow presents challenges in synchronizing rotation speed with jump height, as insufficient air time can lead to under-rotation, while excessive forward lean may cause edge scratches or instability. Higher-rotation versions, such as doubles and triples, are particularly prone to two-foot landings, where the free foot touches the ice upon arrival, often due to inadequate rotational momentum or fear of falling on the landing edge.[13][24] Variations of the Salchow include single, double, triple, and quadruple rotations, with the quadruple first successfully landed in competition by Timothy Goebel in 1998 and Miki Ando in 2002. It is commonly incorporated as the second jump in combinations, leveraging the back outside landing edge to transition smoothly into subsequent edge jumps like the loop or flip.[23]Toe Loop

The toe loop is a toe-assisted jump in figure skating that takes off and lands on the same back outside edge, making it the simplest of the toe jumps due to its straightforward mechanics and minimal preparatory curve. For skaters rotating counterclockwise—the most common direction—the takeoff begins from a backward approach on the outside edge of the right foot, with the left foot's toe pick inserted into the ice close to the skating foot (typically around 0.76 meters away) to initiate a quick pivot and propulsion. This insertion allows for a fluid transition into rotation, generating vertical velocity primarily through leg extension during a brief propulsion phase of approximately 0.14 seconds, while the skater maintains a relatively straight-line entry to avoid excessive curving that could lead to edge issues.[10][23] Technique emphasizes precise timing and body control: the skating leg remains straight without knee lift, lifting off from the heel as the free leg scissored close to the body for rotational momentum, while arms position for balance by lagging slightly behind the hips to absorb takeoff energy rather than driving it. In the air, the skater achieves rotation through a tight position, with shoulders aligning early with the hips (lagging only about 6 degrees in advanced executions) to sustain velocity around 4.8 revolutions per second for higher multiples. Landing occurs on the back outside edge of the right foot, with flight times averaging 0.68 seconds for quadruple attempts, prioritizing a vertical posture at peak height (about 0.55 meters) to complete rotations cleanly.[25][10] One common challenge is over-reliance on the toe pick, which can result in sloppy or cheated edges if the skater twists the takeoff or pre-rotates excessively, often leading to downgrades in competition; this makes it the most frequently mishandled jump despite its simplicity. Its ease in generating power from the assisted takeoff positions the toe loop as the preferred choice for quadruple rotations, as it allows skaters to add multiples more readily than edge-only jumps by maintaining compact air positions without complex edge demands. Variations include the single toe loop, typically one of the first full-rotating jumps learned after basic edge work, progressing to double, triple, and quadruple versions that share the core technique but require increased rotational speed and height for success.[26][23][25]Euler Jump

The Euler jump, also known as the half-loop, is an edge jump that takes off from the backward outside edge of one foot and lands on the backward inside edge of the opposite foot, facilitating connections between other jumps without altering the rotational direction.[6] This maneuver performs a single rotation in the air but is not counted as a full rotational jump element in program requirements, allowing skaters to include it once per free skating program without it contributing to the limit on listed jumps.[27] In technique, the Euler follows a short, curved trajectory with limited air time to preserve momentum, commonly linking jumps that takeoff in the same direction, such as a Lutz-Euler-toe loop combination where it bridges the backward outside landing of the Lutz to the backward inside takeoff of the toe loop.[6] Skaters must execute it with precise timing and minimal interruption to maintain the combination's validity, as any full revolution on the ice between connected elements preserves the sequence.[28] Key challenges include sustaining smooth flow and clean edge quality, as deviations can result in downgrades or reduced base value if the rotation falls short of a half revolution.[28] It was introduced in its current form to enable more intricate jump combinations without necessitating foot or direction changes, enhancing program complexity in modern competitive skating.[6] While primarily performed as a single Euler (1Eu) with a base value of 0.50 in combinations, variations occasionally involve additional rotations, though these are subject to calling as full loop jumps under ISU guidelines.[28] The name "Euler" was formalized by the International Skating Union in 2018 to distinguish it from the loop jump, drawing from its historical use in roller skating and European traditions where it is also called the Thorén after Swedish skater Per Ludvig Julius Thorén.[6]Technique and Execution

Takeoff Phase

The takeoff phase of figure skating jumps begins with the skater building speed via preparatory entry curves or crossovers to generate sufficient horizontal momentum, which is then converted into vertical lift and initial rotation through explosive extension of the knee and hip joints.[29] This propulsion relies on a deep bend in the skating leg to load the muscles eccentrically, followed by rapid concentric extension to push against the ice, achieving vertical velocities typically ranging from 2.5 to 4.0 m/s depending on jump type and skill level.[30] The free leg swings forward and across to contribute to both height and the onset of rotation, with arms often pulled in briefly to aid angular momentum.[29] Edge-specific techniques vary between toe jumps and edge jumps to ensure clean propulsion without loss of control. In toe jumps such as the toe loop or flip, the skater glides backward on the skating foot's edge while timing the insertion of the free foot's toe pick precisely into the ice just before liftoff, allowing a pivot that assists in the half-rotation while the skating leg extends for launch.[29] For edge jumps like the Salchow or loop, the skater maintains pressure on the takeoff edge—typically inside or outside—through controlled lean and avoidance of excessive rocking, preventing "scratches" where the blade flattens and reduces grip on the ice.[29] The Axel, with its forward takeoff, uniquely requires an outside edge approach on the skating foot, integrating a step-forward motion to align the body for upward thrust.[29] Common errors in the takeoff phase often stem from inadequate preparation or execution flaws that compromise height or edge quality. Insufficient knee and hip bend prior to extension results in limited vertical impulse, yielding lower jump heights and shorter air time, which can lead to under-rotation on landing.[29] Taking off from the wrong edge, such as an inside edge instead of outside for a Lutz, is flagged by judges and incurs a downgrade, reducing the jump's base value as if it were one fewer rotation.[18] Pre-rotation—excessive turning on the ice before liftoff—also diminishes the required airborne rotations, often resulting in a "quarter" or "under-rotated" call with corresponding score penalties.[18] From a physics perspective, the takeoff converts frictional impulse from the ice-skate interaction into vertical and rotational velocity components essential for the jump's success. Ground reaction forces during the push-off phase, peaking at 2-3 times body weight, provide the linear impulse that determines takeoff velocity, while torque from asymmetric limb movements generates angular momentum, typically around 130-150 × 10^{-3} s^{-1} (normalized by mass and height squared) across jump types.[31] Horizontal momentum from the entry is partially redirected upward, with efficient energy transfer minimizing losses to heat or vibration, thus maximizing the skater's time in the air for completing rotations.[29]Rotation and Air Position

During the airborne phase of figure skating jumps, skaters accelerate their rotation by pulling the arms and free leg tightly toward the body's rotational axis, thereby decreasing the moment of inertia while conserving angular momentum.[31] This principle allows the skater to achieve the required number of revolutions within the limited air time, as the initial angular momentum generated at takeoff remains constant in the absence of external torques.[8] The free leg is typically crossed behind the landing leg, and arms are drawn across the chest or alongside the torso to minimize the body's radius of gyration.[32] Skaters maintain a compact, upright or semi-upright air position to sustain high rotational velocity, with the core engaged to keep the axis vertical and stable.[31] For multi-revolution jumps, this tight configuration—often resembling elements of a Biellmann or upright spin position adapted for flight—helps counteract any drift from the ideal trajectory. Air time for triple jumps typically ranges from 0.6 to 0.8 seconds, providing just enough duration to complete three full rotations at speeds of approximately 4-5 revolutions per second; quadruple jumps demand slightly longer flight times, often exceeding 0.7 seconds, to accommodate four rotations.[33][31] Key challenges in this phase include over-rotation, where excessive speed leads to completing more than the intended revolutions and compromising landing edge quality, or prematurely checking the spin by opening the body position too soon, resulting in under-rotation.[34] For quadruple jumps, skaters often adopt a "scratch-like" position—characterized by tightly crossed legs and minimal arm extension—for enhanced stability, reducing wobble and preserving rotational efficiency during the extended air time.[31]Landing Phase

The landing phase of a figure skating jump begins as the skater's blade contacts the ice, requiring precise control to absorb impact forces that can exceed three times the skater's body weight. To manage this, the skater employs a flexed "eagle pose" with hips, knees, and ankles bent, particularly emphasizing a deep knee bend on the landing leg to dissipate energy over an extended period through a combination of hip and knee strategies.[29][35] The free leg is extended backward and then swung forward around the body to increase the moment of inertia, while the arms are checked and extended outward to further halt rotation, ensuring a stable touchdown on the backward outside edge of the landing foot.[29] A clean landing demands firm control on the backward outside edge, which is essential for receiving full rotational value and maintaining balance without deviation. Landings on two feet or with a flat blade, often resulting from insufficient edge depth or timing errors, typically lead to instability, potential falls, or downgraded element calls that reduce the jump's technical merit.[29] Common challenges in this phase include under-rotation, where the skater completes fewer than the required full turns due to premature increases in moment of inertia, and wobbles stemming from suboptimal air position that misaligns the body upon entry.[29] Excessive entry speed can also cause skidding or loss of edge grip, complicating the transition to a controlled glide.[35] To recover and sustain momentum, skilled skaters use a technique known as "caressing the ice," where the blade gently traces the surface with subtle pressure to redirect flow and prepare for subsequent elements without abrupt stops.[29] This method preserves the program's rhythm while minimizing deductions for poor quality.[35]Rules and Scoring

Single Skating Requirements

In single skating competitions, the short program requires three jumping passes for both men and women at the senior level: two solo jumps and one jump combination consisting of two jumps. The solo jumps must include one Axel-type jump (double or triple for men, double or triple for women) and one other jump (any triple or quadruple for men, any triple for women), with the combination featuring jumps that differ from the solos, such as a double followed by a triple or two triples.[18] In the free skating, skaters perform up to seven jumping passes, which may include solo jumps, combinations, or sequences, with the requirement to include at least one Axel-type jump among them.[18] Jump combinations in the free skating are limited to a maximum of three jumps linked without full ice coverage between them, often using an Euler jump or half-loop as a connecting element, while sequences allow jumps connected by full ice coverage and receive a factor of 0.8 applied to their total base value. The value of a valid combination is the full sum of the individual jump base values, with no more than two of the same triple or quadruple jump repeated across the program (one of which may be a quadruple), and doubles limited to two total.[18] Base values for jumps are determined by the International Skating Union (ISU) scale, which assigns fixed points based on the jump type and number of rotations; for example, a triple Axel has a base value of 8.0, while a quadruple Salchow is valued at 9.7. The 2025-26 Scale of Values also includes quintuple jumps at 14.0 points each. These values can be adjusted by the Grade of Execution (GOE), ranging from -5 to +5 points depending on the quality of execution, such as precise takeoff edges or controlled air position.[36] At lower levels, such as novice, restrictions limit the maximum rotations to doubles and limited triples, with short programs requiring a single or double Axel, a double or triple jump, and a combination of doubles or double-triple, excluding quads entirely. Senior-level competitions mandate the full seven jumping passes in the free skating, while novice and junior categories impose stricter limits on triple and quadruple attempts to align with developmental progression.[37]Pair Skating Adaptations