Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

First American Regiment

View on Wikipedia

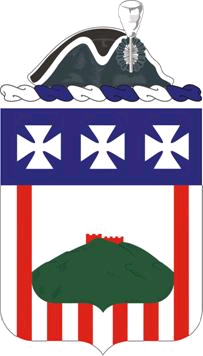

| First American Regiment | |

|---|---|

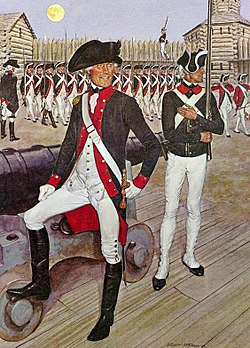

Uniform of the First American Regiment in 1786 | |

| Active | 12 August 1784 – 17 May 1815 |

| Country | |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort McIntosh |

| Nickname | Harmar's Regiment |

| Engagements | Northwest Indian War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Josiah Harmar Jacob Kingsbury |

The First American Regiment (also known as Harmar's Regiment, The United States Regiment, The Regiment of Infantry, 1st Sub-legion, 1st Regiment of Infantry and 1st Infantry Regiment) was the first peacetime regular army infantry unit authorized by the Confederation Congress after the American Revolutionary War. Organized in August 1784, it served primarily on the early American frontier west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1815, following the end of the War of 1812, it was consolidated with several other regiments to form the 3rd Infantry Regiment.

Formation

[edit]After the conclusion of the American Revolution in 1783, Congress ordered the Continental Army to disband, and General George Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief.[1] A Congressional committee under Alexander Hamilton sought opinions on a permanent armed force. Washington submitted his "Sentiments on a Peace Establishment," which called for only a small force, only a 2,631 man regiment to guard the western frontier and the borders with Canada and Spanish Florida.[2] Economic constraints forced the new nation to rely heavily on militia.[3]

While the bulk of the Continental Army was disbanded by the end of 1783, Jackson's Continental Regiment, commanded by Colonel Henry Jackson, and an artillery company under Brevet Major John Doughty remained in service. On June 2, 1784, Congress reissued the disbandment order under the principle that "standing armies in time of peace are inconsistent with the principles of republican government, dangerous to the liberties of a free people, and generally converted into destructive engines for establishing despotism."[4] Jackson's regiment was disbanded later that month, and Doughty's battery was retained at West Point guarding artillery and ammunition.

On June 3, 1784, Congress passed a new resolution:[5]

Resolved, That the Secretary at War take order for forming the said troops when assembled, into one regiment, to consist of eight companies of infantry, and two of artillery, arming and equipping them in a soldier-like manner: and that he be authorised to direct their destination and operations, subject to the order of Congress, and of the Committee of the states in the recess of Congress.

Thomas Mifflin, the president of Congress, named his former aide, Josiah Harmar, to be the commander of the new regiment, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Harmar was commissioned as the regiment's "lieutenant colonel commandant" on August 12, 1784. The regiment was used primarily to man frontier outposts and guard against Native American attacks. Doughty's company became the 2d Continental Artillery Regiment. The regiment's first posting was to Fort McIntosh in Beaver, Pennsylvania. Half of the regiment's enlisted and non-commissioned officers were born outside the United States.[6]

In 1786, Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered Colonel Harmar to the outpost village of Vincennes to restore order. The Kentucky militia, which had been left behind by George Rogers Clark to help defend Vincennes but had become a lawless mob, fled at the approach of the regiment. Harmar left 100 regulars under the command of Major Jean François Hamtramck to build a new fort and conduct operations deep within the Ohio Country.

Northwest Indian War

[edit]The First American Regiment was renamed the Regiment of Infantry on September 29, 1789, when the United States Army was formally instituted under the Constitution of the United States.[7] In 1790, Harmar – who had been breveted as a brigadier general in 1787 – led 320 regulars and over 1,000 militia on the disastrous Harmar campaign in October 1790. The Regiment of Infantry suffered over 70 casualties.

An act of Congress on March 3, 1791, reorganized the U.S. Army to have two regiments of infantry under the command of Major General Arthur St. Clair. As a result, the regiment was designated as the 1st Infantry Regiment with Harmar retained as its commanding officer.[8] It comprised the main force of regulars under St. Clair in the campaign to destroy Kekionga, a large Miami village central to the Northwestern Confederacy of Native American nations. For a brief time, the First American Regiment was commanded by Major John Hamtramck—a French Canadian immigrant—and his second-in-command, Major David Ziegler—a German immigrant.[9]

While on campaign, the 1st Infantry under Hamtramck was sent to find an overdue supply train. The supplies were never found, but as the infantry marched to rejoin the main force on November 4, 1791, gunfire was heard. Native Americans under Miami Chief Little Turtle had attacked in what came to be known as St. Clair's defeat, the worst loss to American Indians by the United States Army in history. Survivors broke through Little Turtle's lines and warned Hamtramck, who fell back to Fort Jefferson instead of covering the retreat.

In response to St. Clair's defeat, the Army was reorganized in 1792 as the Legion of the United States under Major General Anthony Wayne. The First Infantry became the infantry component of the 1st Sub-Legion, commanded by Hamtramck, who was promoted to lieutenant colonel commandant. Under Wayne's leadership, the Legion trained extensively before marching north to meet the Native American confederacy that had defeated St. Clair. The Legion was victorious at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. The trading post at Kekionga was rebuilt and named Fort Wayne and was garrisoned by the First Sub-Legion under Hamtramck. William Henry Harrison, later to become the 9th President of the United States, was a junior officer in the 1st Sub-Legion.[7]

Later service

[edit]

In October 1796, the Legion of the United States reverted to being named the United States Army, and the 1st Sub-Legion was designated as the 1st Infantry Regiment. In 1803, Captain Meriwether Lewis of the 1st Infantry was appointed by President Thomas Jefferson to command the Corps of Discovery which conducted the Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore newly acquired territories of the United States. During the War of 1812, the 1st Infantry served in Upper Canada (Ontario province) and saw action at the battles of Chippawa and Lundy's Lane and the Siege of Fort Erie.

Consolidation

[edit]In October 1815, the 1st Infantry was consolidated with the 5th, 17th, 19th, and the 28th Infantry regiments to form the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard). The 3rd Infantry, with its roots in the First Infantry Regiment, dating back to 1784, is recognized as the oldest regular army regiment in the United States Army.

Commanding officers

[edit]- Brevet Brigadier General Josiah Harmar (August 12, 1784 – January 1, 1792)

- Major John F. Hamtramck (January 1, 1792 – September 4, 1792)

- Major Richard Call (September 4, 1792 – September 28, 1792)

- Major Eskurius Beatty (September 28, 1792 – November 27, 1792)

- Major Thomas Doyle (November 27, 1792 – February 18, 1793)

- Colonel John F. Hamtramck (February 18, 1793 – April 11, 1803)

- Colonel Thomas Hunt (April 11, 1803 – August 18, 1808)

- Colonel Jacob Kingsbury (August 18, 1808 – May 17, 1815)

Notable members

[edit]- Major General and President William Henry Harrison

- Brigadier General Zebulon Pike

- Brigadier General Thomas Humphrey Cushing

- Colonel Thomas Hunt

- Colonel Jacob Kingsbury

- Colonel William Whistler

- Major David Ziegler

- Captain Meriwether Lewis

- Sergeant George Davenport

References

[edit]- ^ ArmyHistory.org (link below). Accessed October 3, 2008

- ^ Weigley, Russell F. (1962). "II. George Washington and Alexander Hamilton: Military Professionalism in Early Republican Style". Towards an American Army. New York City: Columbia University Press. pp. 25–26.

- ^ "The Peace Establishment". U.S. Army Center of Military History. 196. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875. Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume 27, Pg 433 [1]

- ^ Library of Congress website, accessed October 3, 2008

- ^ Skelton, William B. (1989). "The Confederation's Regulars: A Social Profile of Enlisted Service in America's First Standing Army". The William and Mary Quarterly. 46 (4). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 770–85. doi:10.2307/1922782. JSTOR 1922782. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ a b The First Regiment of Infantry Archived October 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine compiled in the office of the Military Service Institution. Website accessed April 9, 2009.

- ^ *U.S. Army. (May 22, 1997.) "Lineage and honors information: 3d Infantry (the Old Guard)" Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. United States Army Center of Military History. Accessed October 22, 2008.

- ^ Winkler, John F. (November 20, 2011). Wabash 1791 (Campaign) (Kindle ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. 356. ISBN 9781849086776.

External links

[edit]- Anthony Wayne and the Battle of Fallen Timbers at ArmyHistory.org